Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a challenge for people living with HIV (PLWH), particularly immune non-responders (INR) with compromised CD4 T-cell reconstitution following antiretroviral therapy (CD4 count <350 cells per mm3). Their diminished vaccine responses raised concerns about their vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections (BTI). Our in-depth study here revealed chronic inflammation in PLWH and a limited anti-Spike IgG response after vaccination in INR. Nevertheless, the imprinting of Spike-specific B cells by vaccination significantly enhanced the humoral responses after BTI. Notably, the magnitude of cellular CD4 response in all PLWH was comparable to that in healthy donors (HD). However, the polyfunctionality and phenotype of Spike-specific CD8 T cells in INR differed from controls. The findings highlight the need for additional boosters with variant vaccines, and for monitoring ART adherence and the durability of both humoral and cellular anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunity in INR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has highlighted the importance of the immune system in controlling natural infections and developing robust humoral and cellular responses to vaccines. High-risk populations include immunocompromised individuals, those with multiple morbidities, lower socio-economic status, and the elderly1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

The susceptibility of people living with HIV (PLWH) to severe COVID-19 outcomes was initially debated9,10. Between 10–40% of PLWH fail to reconstitute their CD4 T cells even after 24 months of achieving virological suppression (defined as immune non-responders, INR), rendering them vulnerable to non-AIDS related conditions such as cardiovascular disease, liver disease, cancer, and neurocognitive dysfunction, consequently heightening the risk of mortality11,12. The etiology of INR includes various factors such as age, gender, genetic predisposition, baseline CD4 T-cell counts, ART regimen, co-infection, residual viral replication, microbial translocation, and disrupted hematopoiesis/thymic output13. This decline in CD4 T-cell production is often compounded by increased T-cell activation, exhaustion, and senescence14,15. Subsequent research demonstrated that INR (defined here as CD4 count <350 cells/μL) are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 disease16,17,18,19,20. In these studies, a CD4 count below 200 cells/mm3 was the primary factor determining the outcome of COVID-19. The conclusions were less definitive for PLWH with efficient ART (defined here as an immune responder with CD4 count >350 cells/μL, IR). This discrepancy might result from the increased common risk factors associated with severe COVID-19 and HIV21. Moreover, PLWH with low CD4 counts have impaired antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines6,8,22,23 (see also supplementary references) and other vaccines24,25,26. HIV replication depletes CD4 T cells in both peripheral blood and tissues, with a notable impact on mucosal CD4 T cells27. This loss, coupled with a dysregulation between Treg/Th17, disrupts intestinal epithelial integrity, leading to microbial translocation and chronic inflammation. Persistent immune activation could even be detected in PLWH with effective ART28.

Pinpointing the precise impact of INR remains challenging, particularly regarding how these factors could influence the immune response elicited by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines or natural infection, including variants of concern (VOC) in vaccinated INR.

This study compares the magnitude of systemic inflammation after BTI in PLWH and HD, contrasted to the massive inflammation detected in samples from severe COVID-19 patients and full-blown bacterial sepsis in non-HIV ICU patients. We also aimed to assess the responsiveness of INR to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines and VOC SARS-CoV-2 BTI, comparing them with those of healthy donors (HDs) after vaccination and BTI29,30,31.

This study sheds light on the concept of hybrid immunity in INR, resulting from both vaccination and natural infection by VOC. It examines the magnitude and quality of the immune response in INR regarding inflammation, humoral, and cellular responses.

Results

Inflammation after breakthrough infection in PLWH

To evaluate whether the inflammatory environment could impair the development of vaccine responses in PLWH, we compared the systemic levels of pro-inflammatory molecules in vaccinated PLWH and HD or non-vaccinated patients with severe COVID-19 (Supplementary Tables S1–S5). Using Olink technology, we defined a proteomic atlas based on the normalized protein expression (NPX) of 92 analytes (Fig. 1A). Expression was compared to values in samples from sepsis patients admitted to the ICU, showing expectedly elevated inflammatory markers (Fig. 1A). The inflammatory profile in PLWH both before and after BTI was distinct from that in non-vaccinated severe COVID-19, and vaccinated HD (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1A). We characterized this signature both in vaccinated PLWH (Vax) and after recovery from BTI (PLWH BTI), noting that only CX3CL1 was significantly upregulated post-BTI in paired samples (p = 0.0098, n = 10) (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1B, C). KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) analysis highlighted pathways linked to viral infections and cytokine signaling (Supplementary Table S6). Moreover, the interaction among pro-inflammatory molecules suggested a strong co-regulation in PLWH (Supplementary Fig. 1D). We particularly found a strong enrichment in pathways related to chemokines (CCL11, CCL19, CCL20, MCPs) and TNF (TNFB, TNFRSF9, TNFRSF14, TRAIL).

A Inflammatory profiles by Olink. Quantification of pro-inflammatory molecules in plasma from HD or PLWH after vaccination (n = 9 and n = 11, respectively), after VOC BTI (n = 20 and n = 10, respectively), or from hospitalized acute severe COVID-19 (n = 11), and sepsis patients (n = 16). NPX (normalized protein expression) values were scaled for each marker. The patient group and disease are indicated by the bar chart on the top. B Specific inflammatory signature of PLWH. Visualization by PCA of the inflammatory profile from vaccinated HD, PLWH, and BTI or unvaccinated severe COVID patients. The patient group is denoted by symbols beneath the graph, and their distribution is outlined by ellipses generated automatically. C Characteristics of the inflammatory signature in PLWH. Visualization by volcano plots of the significant inflammatory molecules detected in vaccinated HD and PLWH before and after BTI, determined by positive serology for anti-nucleocapsid IgG. Significance levels from the Mann–Whitney test are indicated: * for p < 0.05 and ** for p < 0.01. The number of proteins and false discovery rate are indicated for each pathway. See also Supplementary Fig. 1.

We augmented this atlas’s resolution by performing direct ELISA quantification of molecules previously described during the acute phase of infection for severe COVID-19 and BTI32,33, Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2A. We found evidence of activation of innate cells in vaccinated PLWH compared with vaccinated HDs as illustrated by an elevated plasma level of myeloperoxidase (MPO p = 0.011), interferon-gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10, p = 0.0037), and soluble CD163 (sCD163, p < 0.0001). We only noted significant differences for PTX3 (p = 0.0043) and MBL (p = 0.0335) between INR and IR before BTI, Supplementary Fig. 2B34,35. Next, we measured inflammatory markers after BTI in HD and PLWH. For both HD and PLWH, we found the persistent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as GDF-15 (p < 0.0001 for both), IP-10 (p < 0.0001 vs. p < 0.001), and sCD163 (p < 0.0001 vs. p < 0.022), Fig. 2A. The only significant difference was an increased Calprotectin concentration in PLWH, (p < 0.0001). In fact, despite finding significant increases in inflammatory markers in PLWH post- vs. pre-BTI (IP-10, IL-6, sCD163, Calprotectin, GDF-15, PF4, Zonulin, and D-dimer) or significant decreases (Galectin-9, MPO, sCD14), Supplementary Fig. 2A, these were not significantly different from that found in post-BTI in HD. In summary, vaccinated PLWH only exhibited minor abnormalities in inflammatory responses after BTI, suggesting that vaccination limited the magnitude of persistent inflammation induced by a viral infection in PLWH.

A Inflammatory molecules after BTI. Longitudinal quantification of pro-inflammatory molecules in plasma from vaccinated PLWH was assessed by Elisa for the indicated markers before (n = 41, 5 months post-dose 2) and after BTI (n = 16, 4–6 weeks post-BTI). PLWH and HDs were classified according to their history of vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection. As controls, we used unpaired vaccinated HDs (n = 19, 6 months post-dose 2) and a separate group post-BTI (n = 12, 3–4 weeks post-BTI). Mann–Whitney test and two-tailed p-values are indicated for HD and HD/PLWH comparisons with *, **, ***, and **** denoting p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001. B Immune cell subset distribution after BTI. The absolute count of immune cells was performed on freshly collected, paired blood samples from vaccinated PLWH (n = 40, 5 months post-dose 2) before and after BTI (n = 14, 4–6 weeks post-BTI). Mann–Whitney test and two-tailed p-values are indicated for PLWH comparisons with *, ***, and **** denoting p < 0.05, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001. C Specific inflammatory signature of BTI in PLWH. Volcano plots visualize significant inflammatory molecules and immune cells detected before and after BTI, as determined by positive serology for anti-nucleocapsid IgG (left). Visualization by PCA of the immune profile from PLWH, segregated according to INR status, (right). D The correlogram described the significant correlation between the pro-inflammatory molecules and immune cells in vaccinated IR (n = 20) and INR (n = 20) PLWH. Pearson correlations with FDR are indicated with * for p < 0.05 and ** for p < 0.01. See also Supplementary Fig. 2.

We next investigated the modulation of cellular subsets concerning inflammation in PWLH, Fig. 2B. The absolute number of circulating hematopoietic cells was normalized after BTI, and we found decreased numbers of all immune subsets including neutrophils (p < 0.0001), monocytes (p < 0.0001), lymphocytes (p < 0.0001), total T cells (p < 0.001), CD4 T cells (p = 0.024), CD8 T cells (p = 0.0004), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (p = 0.019). To explore the individual cellular dynamics after BTI, we calculated the ratio between total lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 2C). The lymphocytes-to-monocytes ratio (LMR) was increased after BTI in PLWH, demonstrating normalization, while the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and CD4/CD8 ratio showed no significant changes, Supplementary Fig. 2D. Results suggested that vaccination allowed normalization of cell subsets after BTI in PLWH.

To further investigate the individualized immune status of PLWH, we analyzed the change in proteomic (concentration of inflammatory molecules) and cellular (absolute count) data (Fig. 2C). We confirmed that the decrease of monocytes and neutrophils and their related molecules (sCD14, Galectin-9, LBP, and Calprotectin) was associated with BTI (defined by the detection of anti-Nucleocapsid IgG), and a normal recovery in the absence of severe disease. The differences between vaccinated INR and IR were discrete, except for the absolute count of neutrophils in INR and monocytes in IR, Fig. 2C. The immune network analysis revealed significant inflammatory and cellular networks for IR (B/T cells) and INR (Neutrophils/T cells, IL-6/IL-18), Fig. 2D.

Humoral immune response after BTI in PLWH

We monitored the humoral response to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine by measuring IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 wildtype (Wuhan) RBD levels post-vaccination (Fig. 3A). The humoral response was lower in vaccinated INR (median 223 BAU/mL, IQR from 68 to 911) than in IR (median 931 BAU/mL, IQR from 217 to 1659) (p = 0.042), with a higher non-response rate of 50% (11/21) in INR compared to 23% (4/17) in IR (cut-off set at 200 BAU/mL). However, BTI significantly boosted the humoral response in INR (median 5494 BAU/mL, IQR from 1948 to 37506, p < 0.0001). It should be noted that a higher percentage of INR (60%) than IR (17%) received a third vaccine dose before BTI sampling. We also found increased anti-nucleocapsid responses in IR, but not in INR. Most IR (3/5) developed a de novo response against Nucleocapsid (p = 0.034), while INR showed a limited response (18% of patients, 2/11) after BTI.

A Quantification of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies after BTI in PLWH (n = 16, 4–6 weeks post-BTI). Scatter plots with medians are shown. Dotted lines demarcate ranges ( > 2000, 200–2000, 20–200 BAU/mL), to visualize patients with good, low, and non-seroconversion, respectively. The VOC-specific serology (IgG anti-nucleocapsid combined with anti-BA1 or -BA2) was detailed before and after BTI in PLWH stratified by immune status (INR vs. IR). Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p-values < 0.05 (*), values < 0.01 (**), values < 0.001 (***), and <0.0001 (****). B Quantification of RBD, Spike, and Nucleocapsid-binding B cells in PLWH after vaccination and BTI. Left: Frequency of SARS-CoV-2 -binding B cells including Spike+ RBD+, Spike+ RBD- or Nucleocapsid after the vaccine in HD (n = 11, 5–6 months post-Dose 2) vs. PLWH (n = 41, 4–5 months post-Dose 2) or natural infection in convalescent COVID-19 (n = 18, 1-month post-infection) or BTI in HD (n = 14, 4–6 weeks post-BTI). Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p-values < 0.05 (*), values < 0.01 (**), values < 0.001 (***), and <0.0001 (****). Right: Longitudinal frequency of SARS-CoV-2 -binding B cells including Spike+ RBD+, Spike+ RBD- or Nucleocapsid after BTI in PLWH (n = 16, 4–6 weeks post-BTI). Wilcoxon matched-pair signed rank test, with ** and *** denoting p < 0.01 and p < 0.001. C Peripheral detection of anti-RBD humoral immunity in PLWH. Correlation plots between the concentration of anti-RBD IgG (Log10 transformed BAU/mL) and the frequencies of SARS-CoV-2 RBD- or Spike-binding B cells in total B cells from peripheral blood of PLWH stratified by immune (CD4 count) and infection (BTI) status. Pearson correlations are indicated with * for p < 0.05 and ** for p < 0.01. D Anti-SARS-CoV-2 humoral signature of PLWH after vaccination (n = 41) and BTI (n = 16). Visualization by PCA of WT or VOC IgG anti-RBD serological concentration, anti-Spike, and anti-nucleocapsid. Ellipses were automatically generated to delineate PLWH based on Immune (INR vs. IR) and infection status (vaccination vs. BTI). E Phenotype of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-binding B cells in PLWH after vaccination (n = 41, 4–5 months post-Dose 2). Frequency of Spike- and RBD-binding B cells expressing CD21, CD24, CD27, CD38, CD71, IgD, IgG, or IgM after the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the different groups with a p-value of * for p < 0.05. See also Supplementary Fig. 3.

The specificity of the humoral response was assessed by quantifying antibodies against Spike and RBD proteins specific to VOCs (Omicron BA.1 or BA.2). The pre-BTI antibody levels reflected cross-reactivity between the Wuhan strain and VOC. After BTI in INR, there was an increase in IgG anti-RBD (p = 0.0015 for both BA.1 and p = 0.0035 for BA.2) and IgG anti-Spike (p = 0.0006 for BA.1 and p = 0.012 for BA.2), Fig. 3A.

The persistence of the humoral response depends on the half-life of antibodies and the longevity of antigen-specific B cells. We used tetramer staining of PBMC directly ex vivo to identify SARS-CoV-2 binding B cells in non-vaccinated COVID-19 patients, vaccinated HD, vaccinated BTI, and PLWH before and after BTI, Supplementary Fig. 3A. The frequencies of vaccine-elicited responses including RBD- and Spike-binding B cells, were lower in PLWH than in vaccinated HD at similar post-vaccine time-points (p = 0.015 and p = 0.0002 for RBD in IR and INR, respectively, p = 0.0199 for Spike in INR) (Fig. 3B, left). BTI induced an increase of RBD-, Spike-, and Nucleocapsid-binding B cells (p = 0.0017, p = 0.0009, and p = 0.0098, respectively), Fig. 3B, right.

We next investigated the correlation between anti-RBD IgG and the frequencies of SARS-CoV-2 binding B cells in PLWH (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). Positive correlations were established in INR pre- and post-BTI for RBD (p = 0.0217 and p = 0.0072) or Spike in vaccinated INR (p = 0.0342).

The strong correlation between CD4 T-cell count and B cells (p < 0.0001, r = 0.75) or follicular helper T-cell counts (p < 0.0001, r = 0.82, Supplementary Fig. 2D), prompted us to hypothesize that the hypo-responsiveness to the vaccine in INR might correspond to an overall impairment of humoral immunity. We, therefore, also examined the antibody response against other viral infections in PLWH, Fig. 3D. While no significant difference was observed regarding CMV serostatus, INR presented stronger responses against EBV and seasonal influenza virus than IR, suggesting chronic viral infections possibly due to a deficit in humoral responses in INR. The humoral response against non-COVID-19 viral epitopes was preserved after BTI.

Finally, the phenotype of SARS-CoV-2 binding B cells was evaluated pre- and post-BTI to assess the quality and potential duration of the response (Supplementary Fig. 3A). INR exhibited increased surface expression of CD21 and decreased expression of CD27 on SARS-CoV-2 binding B cells compared to IR and/or HDs (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, the phenotype of SARS-CoV-2 binding B cells was compared between vaccinated HD and PLWH, irrespective of immune status (Supplementary Fig. 3D). We found that PLWH had fewer memory markers such as CD24, CD27, CD71, and IgG, demonstrating that PLWH had a limited B-cell memory vaccine response. We also observed that the differentiation status of SARS-CoV-2 binding B cells (CD24, CD27, CD38) was modulated after BTI in PLWH, thereby suggesting functional changes, including antibody secretion.

To demonstrate the impact of vaccination on B-cell specificities, we analyzed non-vaccinated COVID-19 convalescents. We found that nucleocapsid-specific B cells remained consistently dominant over anti-Spike or anti-RBD, Supplementary Fig. 3E. This was markedly different from vaccinated donors, where nucleocapsid responses were lower, regardless of the cohort. Thus, vaccination impacted the frequency of specific B cells in vaccinated PLWH and HD.

Phenotype of T cells response after BTI in PLWH

Given the significant alterations in T-cell subsets during viral infections, such as bystander activation, exhaustion, senescence, or lymphodepletion, we next examined bulk T-cell phenotypes in the cohorts, Supplementary Fig. 4. The expression of activation markers (CD38, HLA-DR) and the exhaustion molecule TIGIT were increased on CD4 T cells from vaccinated INR or after BTI (compared to that found respectively for COVID-19 patients and BTI HD), Supplementary Fig. 4B. A similar activation profile (CD38 combined with the down-modulation of CD127) was observed for CD8 T cells from all PLWH, Supplementary Fig. 4C, D.

To define vaccine-elicited Spike-specific T cells, we first tested functional responses using an in vitro combined Activation Induced Marker /Intracellular Cytokine Staining assay (AIM/ICS) (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 5). Spike-, non-Spike-SARS-CoV-2, and HIV-GAG-specific T cells were defined by upregulation of CD137 and CD154 (for CD4) or the secretion of IFNγ/TNF (for CD8). There was no significant difference in the fraction of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 or CD8 T cells between vaccinated IR and INR (Fig. 4B). Responses were thus independent of INR/IR status. CD4 responses were significantly higher towards Spike compared to GAG, which was predominantly found in the CD8 T-cell response.

A The functionality of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-specific T cells post-vaccination. Representative Dot plots of antigen-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells from vaccinated PLWH (n = 41, 4–5 months post-Dose 2). Antigen-specific T cells were identified by the expression of CD137+CD154+ for CD4 T cells and IFNγ/TNF for CD8 T cells following overnight stimulation with overlapping peptides coding for wild Type Spike (Wuhan) and HIV GAG (p24). Non-stimulated (NS) and Cytostim (CS) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. B Functionality of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-specific T cells post-vaccination according to the immune status of PLWH, top. Frequency of Spike-specific T cells after the second dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. PLWH were classified according to CD4 count at inclusion in the study. Antigen-specific T cells were gated as in A). The unspecific T-cell staining was removed as background from total Spike WT and HIV GAG response to display only virus-specific cellular response. Functionality of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells after BTI, bottom. PLWH (red violin plots), COVID-19 convalescents (white violin plots), and vaccinated HDs (blue violin plots) were classified according to their history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. Mann–Whitney two-tailed p-value with * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001 and **** for p < 0.0001. C The breadth of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells from PLWH BTI. Biplots represent the defined functionality of CD4 (top) and CD8 T cells (bottom) in response to Spike or MNO or GAG-derived peptides for each patient group (BTI PLWH, n = 16, 4–6 weeks post-BTI or COVID-19 convalescent, n = 18, 1-month post-infection). D Polyfunctionality of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells in PLWH. SPICE analyses for in-depth functional profiling of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells. Boolean gates were used to define the 8 possible combinations of IFNγ, TNF, and IL-2 on SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells identified by the upregulation of CD137 and CD154 after overnight stimulation with Spike- or non-Spike-derived peptides. SPICE pie charts represent the median frequency for each of the 8 possible functional profiles of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells. The arcs indicate the proportion of cells that express IFNγ (red), TNF (green), and/or IL-2 (yellow-green). The antigen specificity and vaccination/infection status are indicated inside and above, respectively, for each pie chart. E Polyfunctionality of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 T cells in PLWH. SPICE analyses for in-depth functional profiling of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 T cells. Boolean gates were used to define the 32 possible combinations of IFNγ, TNF, Granzyme B, Perforin, and CD107a on SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 T cells identified by the upregulation of IFNγ and/or TNF after overnight stimulation with Spike- or non-Spike-derived peptides. SPICE pie charts represent the median frequency for each of the 32 possible functional profiles of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 T cells. The arcs indicate the proportion of cells that express CD107a (green), Granzyme B (yellow), IFNγ (green), Perforin (blue), and/or TNF (purple). The antigen specificity and vaccination/infection status are indicated inside and above, respectively, for each pie chart. See also Supplementary Fig. 5.

Further, we compared responses in PLWH after BTI with COVID-19 patients in the acute (day 7) and convalescent phases (3–12 months after infection), Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 5A, B. Spike-specific CD4 T-cell response was increased after BTI in all PLWH, independently of their immune status (p < 0.001 for both INR and IR). This anti-Spike helper T-cell response was even stronger than that observed in non-vaccinated COVID-19 patients during convalescence (p < 0.01). The response against non-Spike derived epitopes (Membrane, Nucleocapsid, Orf1a/b (MNO), see “Methods”) was observed in half of PLWH after-BTI (50%, 8/16) compared to a higher percentage in COVID-19 patients assessed during acute hospitalization or the convalescence phase (78%, 25/32, data not shown). The enhancement of the cytotoxic response against SARS-CoV-2 Spike epitopes after BTI was limited in PLWH and the induction of an MNO-specific CTL response was observed in only 44% (7/16) compared to 72% of COVID-19 patients (23/32). Thus, vaccination favored Spike responses after BTI in both HD and PLWH, similar to a vaccine imprint observed for Spike vs. Nucleocapsid for B-cell immunity above.

Next, we investigated whether the quality of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune response in PLWH after BTI differed from that in convalescent COVID-19 patients (Fig. 4C). In 25% of PLWH, a global CD4 T-cell response was observed only against Spike but not against non-Spike. The polyfunctionality of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells was studied according to the number of vaccine doses and infection status, Fig. 4D, E. The polyfunctionality of Spike SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells from PLWH differed from HD after vaccination (p = 0.003 at 1 month after dose 1 (D1m1), p = 0.0044 at 1 month after dose 2 (D2m1), and p = 0.0002 at 1 month after dose 3 (D3m1)), from convalescent patients (p = 0.031), from HDs after BTI (p = 0.0006) or in PLWH after BTI (p < 0.0001). Significant differences in the polyfunctionality of CD4 T cells responding to non-Spike in PLWH after BTI were observed compared to COVID-19 (p = 0.014), and HD after BTI (p = 0.016).

The non-Spike CD8 T-cell response was dominant in convalescent COVID-19 patients and characterized by an effector cytotoxic profile, as indicated by the expression of Perforin, Granzyme B, and CD107a, Fig. 4C. PLWH after BTI (with detectable CD8 T-cell response) exhibited a similar profile of Spike and non-Spike CTL regarding the expression of Perforin and Granzyme B but had reduced levels of the degranulation marker CD107a, indicating lower cytotoxic potential. Interestingly, the anti-GAG response had higher CD107a levels than the anti-Spike CTL response, demonstrating that full-blown cytotoxic CTL function could nevertheless develop in these patients. The polyfunctionality of Spike SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 T cells after vaccination differed between PLWH and HDs (p = 0.0187 at D2m1, and p = 0.0026 at D3m1), and between PLWH vs. recovered convalescent (p = 0.0021), Fig. 4D. No significant modulation was observed for Spike-specific CD8 T cells after BTI for PLWH (p = 0.1864). The polyfunctionality of non-Spike-specific CD8 T cells after BTI differed between PLWH and HD (p = 0.0151). Finally, anti-GAG-specific CD8 T cells were comparable to Spike in vaccinated PLWH (p = 0.0724, ns) but different from Spike in vaccinated D3m1 HD (p = 0.0041).

Ex vivo cytotoxic T-cell response after BTI in PLWH

To accurately determine the frequency and phenotype of peptide-specific CD8 T cells directly ex vivo, we used peptide-HLA multimers combined with high parameters flow cytometry (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. 6A). The median frequency of Spike-specific multimer CD8 T cells in PLWH after vaccination was similar to EBV-specific multimer CD8 T cells and slightly lower than CMV-specific multimer CD8 T cells, Fig. 5B. The frequencies of Spike-specific CD8 T cells were not significantly different between HD, INR, and NR.

A Detection of Spike-specific CD8 T cells after BTI in PLWH. MHC-Class I restricted multimers were used to identify ex vivo Spike-, CMV-, and EBV-specific CD8 T cells. Left flow plots: illustrative example of staining of CMV/EBV-specific CD8 T cells (x-axis) vs. Spike-specific CD8 T cells (y-axis) in PLWH before and 4-6 weeks after BTI. B Quantification of Spike-specific CD8 T cells in vaccinated PLWH. Top scatterplot: Frequency of virus-specific multimer CD8 T cells after Dose 2 of the mRNA vaccine in all PLWH (n = 41, 4–5 months post-Dose 2) or PLWH stratified according to CD4 count (Bottom scatterplot) (including up to three different HLA per donor among HLA*A0101, HLA*A0201, HLA*A2402, and HLA*B0702). C Quantification of Spike-specific CD8 T cells in PLWH after BTI (n = 16, 4–6 weeks post-BTI). Longitudinal frequencies of paired Spike-, CMV-, and EBV-specific multimer CD8 T cells are shown, red symbols: patients with anti-Nucleocapsid IgG-detected BTI, blue dots: Vaccinated only. Wilcoxon matched-pair signed rank test, with **, denoting p < 0.01. D Phenotype of virus-specific CD8 T cells in PLWH after BTI. Heat plot represents the frequency of markers expressed by virus-specific multimer CD8 T cells (CMV, EBV, FLU, Spike SARS-CoV-2) according to immune status (vaccination vs. BTI) in HD or PLWH depending on CD4 Count (IR vs. INR) and HLA-restriction. E Signature of Spike-specific CD8 T cells in PLWH after BTI. Principal component analysis of Spike-specific dextramers phenotypes identified by flow cytometry in PLWH after vaccination (n = 41) or BTI (n = 16). Ellipses were automatically generated to illustrate the distribution of each patient group. See also Supplementary Fig. 6.

After BTI, we found an increased frequency of Spike-specific CD8 T cells, in PLWH (p < 0.01), while there was no modulation of CMV- and EBV-specific CD8 T cells, Fig. 5C. Further phenotyping of virus-specific CD8 T cells showed Spike-specific effector responses in all PLWH and responses after BTI corresponded to a more activated effector profile, Fig. 5D. This analysis stratified the phenotype of virus-specific CD8 T cells before and after BTI in vaccinated PLWH according to viruses, immune status, type of donor (IR or INR vs. HDs), and HLA. In PLWH, Spike-specific CD8 T cells expressed markers related to effector function (KLRG1+GPR56+CD244+), as well as activation markers (PD-1+HLA-DR+). Next, a principal component analysis of the phenotypes of Spike-specific CD8 T cells before and after BTI (Fig. 5E) showed that INR separated from IR and HD by expressing activation and differentiation markers (HLA-DR, GPR56, CD57, KRLG1), independently of patients’ HLA.

Discussion

We found that vaccinated PLWH had a specific innate inflammatory signature but developed only minor inflammatory abnormalities after BTI. PLWH with impaired CD4 T-cell reconstitution post-ART (INR) had a reduced IgG anti-RBD response after standard vaccination, with 50% being humoral non-responders, but with preserved cellular responses.

The seroconversion rate and the generation of neutralizing antibodies post-vaccination (or primary infection) are crucial to prevent reinfection36. The reduced humoral response might contribute to the elevated risk of BTI in INR37,38. The serological titer of IgG anti-RBD significantly increased after BTI in both IR and INR. This response correlated with anti-RBD B-cell frequencies that were low after vaccination but increased following BTI. Spike-specific B-cell responses predominated in vaccinated individuals showing a vaccine imprint, while non-vaccinated COVID-19 convalescents had a more dominant nucleocapsid response.

HIV induces inappropriate B-cell activation and response to stimulation with suboptimal responses to vaccination39, especially in INR patients with low CD4 counts24. The direct correlation between CD4 count and seroconversion after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in PLWH has been confirmed in a meta-analysis that included multiple risk factors40. These results confirm our findings of significantly lower IgG anti-RBD responses in INR. Other parameters also need to be considered, such as the age of patients. Elderly PLWH has significantly lower IgG-anti-RBD41,42 and lower durability than controls42.

The humoral response constituted the main difference between INR and IR, with significantly reduced anti-RBD IgG after the second dose in INR. A third dose of vaccine has recently been shown to improve seroconversion in most immunocompromised patients43 and to prevent early waning of anti-SARS-CoV-2 binding IgG antibodies in IR44. The durability of the humoral response is overall reduced in PLWH after two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine45, but further studies are required to document the decline rate of neutralizing antibodies in INR after BTI. The serological profile of INR is also distinct in response to seasonal and latent viral infections such as EBV46,47. We cannot rule out that this difference results from HIV-associated impairment. However, no serious adverse events, such as EBV or CMV reactivation, were described in our cohort. The anti-SARS-CoV-2 serological profile is also specific in INR. It is possible that the increased titer of antibodies against VOC after BTI is due to longer infection or prolonged viral shedding in INR. The nature of secreting antibodies is determined by the phenotype of B cells, and therefore, an explanation could be that PLWH has developed defective B cells, responsible for inefficient humoral response15. In line with this, the IgM predominance for Spike/RBD-binding B cells rather than IgG in PLWH was combined with a reduced expression of memory markers (CD24, CD27, CD71) but an increase of the CD21, marker linked to transitional B cells48,49. This population of B cells has already been detected during HIV infection50 in response to CD4 T-cell lymphopenia, chronic immune activation, and persistent alteration of the germinal center27,51. Nevertheless, BTI induced the maturation of these transitional B cells into memory B cells expressing CD27 in INR. The natural waning of humoral responses52,53, the mutation of RBD epitopes, and the persistence of long-term memory antibody-secreting B cells in a chronic inflammatory environment such as in INR can constitute multiple hurdles for long-term protection against future VOCs. This delayed, and partially immature response could be worrying in light of successive VOC waves that can evade antibody protection54,55,56 and confer increased transmissibility57,58. Booster vaccinations with mutated Spike and/ or epitopes not derived from Spike might improve the humoral immunity in INR59,60.

As described previously, the SARS-CoV-2-specific-CD4 T-cell response was robust after natural infection in non-vaccinated PLWH61,62,63,64 and vaccination65,66,67,68,69. Most of these studies were performed on PLWH on stable ART with well-controlled viremia. Here, Spike-specific T-cell frequencies were comparable to HDs after vaccination, but 25% of INR did not develop immune responses against non-Spike after BTI. Similarly, around 30% of vaccinated INR PLWH (median CD4 count of 254 cells per mm3) had no T-cell response70. Vaccination still favored Spike T-cell responses over non-spike responses after BTI, as evidence of a vaccine effect, contrasting with the situation in non-vaccinated COVID-19 patients who had dominant non-spike responses. Therefore, we demonstrated a vaccine effect in HD and PLWH regardless of INR/IR status. Spike-specific T-cell immunity is less affected by mutations71,72,73,74, and evidence thus far indicates that T cells play a critical role in protection against severe COVID-1975, are necessary for early resolution of COVID-1976,77, and even more for protection against severe infection in settings of low antibody levels78,79,80. Moreover, in contrast to decaying antibody titer, SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell memory was durable (around 6 months) and comparable between PLWH69 and non-HIV infected donors75,81. The limited induction of CD8 responses found by others in vaccinated patients after primary infection82 has therefore raised concerns for high-risk PLWH. As helper CD4 T cells may support and sustain the expansion of CD8 T cells, the low CD4 counts in INR could also have limited the induction of the cytotoxic response.

Chronic HIV infection leads not only to quantitative but also qualitative immune defects that are not entirely restored by ART83. So, despite a comparable magnitude of T-cell response, the polyfunctionality of SARS-CoV-2 T cells from vaccinated PLWH was affected in comparison to HDs in our cohort. These defects were combined with an ex vivo activated effector phenotype of Spike-specific CD8 T cells in INR after both vaccination and BTI. The consequences of the reduced polyfunctionality and PD-1 expression on Spike-specific CD4 T cells prompted us to monitor carefully the durability of protection against future infections63. Moreover, the frequency of PD-1+ memory CD4 T cells has been associated with long COVID/ post-acute sequelae (PASC) in PLWH recovering from SARS-CoV-2 infection63. The four-fold higher odds of PASC in PLWH were also strongly associated with chronic inflammation (IP-10, IL-6) that is usually linked to persistent co-morbidities such as cardiovascular and metabolic complications. We describe here chronic inflammation, including the activation of innate immunity in vaccinated PLWH, that persists after BTI. This inflammation was mild even in INR, as observed previously with HDs infected with Omicron and Delta variants84,85. Interestingly, some molecules associated with microbial translocation (and monocyte activation), such as sCD14, LBP, and Galectin-9, were normalized in the systemic circulation after BTI. This down-modulation could be in part due to decreased differentiation into monocyte lineage and/or to recruitment into tissues86.

Despite the notable strengths of this study, such as its in-depth analysis of a homogeneous cohort of PLWHs (age, gender, co-morbidities, and social factors) and comprehensive high-dimensional analysis of the SARS-CoV-2-specific adaptive immune response following natural SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination in PLWH and those without HIV, several limitations need to be considered. First, even if the broad clinical and immunological data set from sixteen PLWHs is substantial for a longitudinal study, it remains relatively modest in terms of serological analyses and clinical trials. Specifically, the study fully sampled only fourteen vaccinated INR following BTI. Second, due to good adherence to ART, our cohort has well-controlled viremia and no patients with very low CD4 count ( < 200 cells/mm3). No severe COVID-19 was observed for the PLWH following BTI, and therefore the systemic inflammation was limited compared to positive control cohorts (ICU COVID-19 and sepsis patients). Moreover, at the sampling times, most PLWH had already received at least two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. In order to evaluate the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination efficacy in PLWH, we compared them with vaccinated HD and included non-vaccinated convalescent COVID-19 to document the immune response following natural primary infection or BTI in INR with suboptimal vaccination efficiency. However, the comparison of variant-specific immune memory induced by vaccination vs. infection was constrained by circulating strains (WT/Alpha vs. Delta/Omicron), with no inclusion of more severe disease for HD. Additionally, while the sampling time-points for infection align with those of the vaccination studies, they were self-reported due to the cessation of PCR-based COVID-19 registration during the Omicron surge. Samples were longitudinally collected after a positive serology test or self-questionaries (BTI) rather than immediately post acutely positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test in most instances. The duration of infection, the risk of prolonged viral shedding, and viral evolution in immune-compromised patients have been debated87, with particular concerns about genomic surveillance and ART adherence88. Finally, the durability of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune response and the potential risk of reinfection have not been documented here, and it would be crucial to understand whether the activated effector profile of T cells could entail increased susceptibility or increased HIV viral blips89.

Our in-depth analyses of vaccine and hybrid immunity showed a surprisingly robust T-cell immunity after mRNA vaccination, demonstrating the capacity of vaccine-mediated immunity even in PLWH with low CD4 counts and despite low serological responses. With regard to the incomplete conversion of memory B cells, skewed phenotype, and reduced polyfunctionality of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells, further variant booster vaccination, and close health monitoring (ART adherence, genomic screening) are indicated to limit prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection and long COVID.

Methods

Study participants

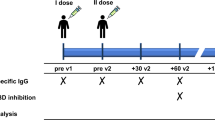

In an observational study (CS041), a total of 41 PLWH were recruited before SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination and stratified based on peripheral CD4 T-cell count as Immune Non-Responder ( < 350 per μL, n = 21, INR) and Immune Responder ( > 350 per μL, n = 20, IR), as shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 and Supplementary Fig. 7. Longitudinal follow-up of vaccinated PLWH allowed the identification of patients suffering from COVID-19 (HIV BTI, n = 16), by positive serology for anti-nucleocapsid IgG. Time-points for BTI for individual PLWH were defined according to the patient’s self-declaration of COVID-19, verified by serological measures. 6/21 INR had transient CD4 > 400 cells/µL during the last years, but only 3 INR had CD4 count >500 cells/µL. We defined a cut-off of 2000 BAU/mL, 1 month after previous mRNA vaccine doses, to identify vaccine-induced seroconversion (standardized WHO units). PLWH received essentially mRNA-based vaccines (BNT162b2, Pfizer-BioNTech or mRNA-1273, Moderna) except one patient for the first dose of vaccine (ChAdOx1, AstraZeneca).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) samples were collected from PLWH after dose 2 (n = 41), and after BTI (n = 16).

The anti-SARS-CoV-2 humoral and cellular immune responses in non-hospitalized PLWH were compared to three control groups: (1) the immune responses observed in HIV-negative hospitalized COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe disease recruited in 2020 (Cohort 1, n = 20 with follow-up from day 7 up to one year) with the Wuhan wild type SARS-CoV-2 variant. See Supplementary Table S3 for cohort details. (2) A cohort with severe COVID-19 recruited in the period 2020-21 infected with SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan and Alpha variants (Cohort 2, n = 17) (Supplementary Table S3). (3) Vaccinated non-hospitalized patients with BTI with either Delta or Omicron (n = 37), (Supplementary Table S4). All patients aged ≥18 years admitted to the hospital with polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-confirmed SARS-2-CoV-2 infection were eligible for inclusion. Blood samples were obtained from each patient within 48 h of admission and up to 10 days during hospitalization, as well as at 3-month and 12-month follow-ups in a subset of patients for cohorts 1 and 2. From December 2021, adults with positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test, with or without positive Omicron or Delta variant PCR on oro-nasopharyngeal specimens (i.e., verified or suspected Omicron/Delta variant cases, respectively), and symptomatic household members of suspected Omicron cases were consecutively recruited to a prospective cohort study [a joint venture between The Norwegian Corona Cohort (NCT04320732) and the Norwegian SARS-CoV-2 study (NCT04381819)]. Pre-2019 pandemic or pre-vaccination healthy donors (HD), as well as SARS-CoV-2 naïve healthy donors after 2nd doses of vaccines (n = 19), were used as controls. Patients with sepsis but without HIV or SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) were used as a validation cohort for the inflammatory response (n = 16, Supplementary Table S5). Sepsis patients (n = 16) conforming to Sepsis-3 criteria, were sampled at hospital admission90.

Ethical considerations

All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in South-Eastern Norway (REK #106624 for the Norwegian SARS CoV2 cohort and REK 1.2007.83 and 2015/629 for the PLWH cohort).

Sample preparation

Each sample consisted of two frozen aliquots with an average cell number of 10 million cells and viability above 95% per donor. Samples were thawed at 37 °C and immediately transferred into a complete RPMI medium (10% FCS, 1% penicillin /streptomycin, glutamine, 10 mM HEPES). After the first wash, thawed cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with DNAse (STEMCELL). Live cells were purified by removing dead cells using a column-based magnetic depletion approach according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Miltenyi). Vaccinated healthy donor PBMCs matched for at least one of the donor HLA alleles were included in each experiment as a control for specific T-cell identification. VeriCells were included in each experiment as a control for phenotypic markers.

HLA typing

PLWH and HD were pre-typed by flow cytometry for A02, A24, and B07 expression. Frozen PBMCs from individuals positive for specific HLA were subsequently stained with the corresponding Dextramers/ Tetramers Class I restricted (HLA-A*01:01, HLA-A*02:01, HLA-A*24:02, and HLA-B*07:02) as described33. The non-SARS-CoV-2-related viruses were used as an internal control for the same individuals (CMV, EBV, Influenza, see Supplementary section).

Inflammatory markers

The following enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were used according to manufacturer protocols. From R&D Systems: Human CD14 DuoSet ELISA (DY383), Human CD163 DuoSet ELISA (DY1607), Human LBP DuoSet ELISA (DY870-05), Human Galectin-9 DuoSet ELISA (DY2045), Human GDF-15 Quantikine ELISA Kit (DGD150), Human CXCL4/PF4 Quantikine ELISA (Kit DPF40), Human IFN-alpha (41100); from Ebioscience: Human MPO Instant ELISA Kit (BMS2038INST); from Thermo Scientific: Invitrogen novex IP 10 Human ELISA Kit (KAC2361); from Abcam Human C-Reactive Protein/CRP (Ab99995); from MyBioSource: Human zonulin ELISA Kit (MBS706368); from Meso Scale diagnostics: human Calprotectin (F21YB-3).

Olink® Target 96 inflammatory panel

The systemic inflammation of PLWH, after vaccine dose 2 or BTI and controls (vaccinated HD, BTI, or severe COVID-19 patients) was determined by analyzing CPT plasma samples by Olink Proteomic Proximity Extension Assay (PEA) technology. The Olink® Target 96 inflammatory panel was used on an Olink® Signature Q100 instrument according to the manufacturer´s instructions.

Flow cytometry

Cryo-preserved PBMCs were enriched for live cells by magnetic depletion of dead cells (Dead cells removal microbeads, Miltenyi) in the presence of Citrate buffer and stained with antibody panels to quantify and characterize the phenotype of specific T-cell responses directed against Spike peptides (two million cells per sample) and B-cell responses to RBD or Spike protein (one million cells per sample). Cells were acquired on a BD FACSymphony (BD Biosciences) or Attune NxT (ThermoFisher).

MAbs were for BD FACSymphony: BB515 Mouse Anti-Human CD279 (PD-1) Clone EH12.1, BD Biosciences, PerCP-eFluor 710, KLRG1 Monoclonal Antibody (13F12F2), eBioscience, PE/Cyanine7 anti-human GPR56, Clone CG4, Nordic Biosite, Alexa Fluor 700 anti-human CD244 (2B4), clone C1.7, Nordic Biosite, APC/Cyanine7 anti-human HLA-DR, clone L243, Nordic Biosite, BV480 Rat Anti-Human CXCR5 (CD185) (Clone: RF8B2) BD Biosciences, BB515 Mouse Anti-Human CD38, clone, HIT2 BD Biosciences, Brilliant Violet 570™ anti-human CD3, Nordic Biosite, Brilliant Violet 605, CD127 Mouse anti Human, Clone HIL 7R M21, BD Biosciences, Brilliant Violet 650, CD161 Mouse anti Human, clone: DX12, BD Biosciences, BV711 Mouse Anti-Human TIM-3 (CD366), clone 7D3, BD Biosciences, BV750 Mouse Anti-Human CD8, clone SK1, BD Biosciences, Brilliant Violet 785™ anti-human CD57 Recombinant, clone QA17A04, Nordic Biosite, BV421 Mouse Anti-Human CD319 (CRACC), BD Biosciences, BUV395 Mouse Anti-Human TIGIT, clone 741182, BD Biosciences, Live/dead™ Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit, for UV excitation, ThermoFisher Scientific, BUV563 Mouse Anti-Human CD45RO, clone UCHL1, BD Biosciences, BUV615 Mouse Anti-Human CD95, clone DX, BD Biosciences, BUV661 Mouse Anti-Human CD4, clone SK3, BD Biosciences, BUV737 Mouse Anti-Human CD38, clone HB7, BD Biosciences, BUV805 Mouse Anti-Human CD27, clone L128, BD Biosciences. VeriCells PBMC (BioLegend) were included as controls.

Frequency values were calculated based on the percentage of the parent immune cell population, and phenotypic markers were gated individually for each sample and calculated as % of positive cells. High-dimensional phenotypic profiles and sample distributions were shown using uniform manifold approximation and projection. Data analysis was performed using CYTOGRAPHER® (ImmunoScape cloud-based analytical software), custom R-scripts, GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software), and FlowJo v10 software (BD Life Sciences). Statistical significance was set at a threshold of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Detection of specific memory CD8 T cells

Antigen-specific CD8 T cells were detected by peptide: HLA multimers as described33 (see Supplementary section and Supplementary Table S7 for an overview). The peptides listed below are referenced individually in the Supplementary Section. Spike-Specific CD8 were detected using PE-conjugated Dextramers (Immudex) targeting Spike and restricted to HLA-A*0101 (LTDEMIAQY), HLA-A*0201 (YLQPRTFLL), HLA-A*2402 (QYIKWPWYI), and HLA-B*0702 (SPRRARSVA). The panel was expanded using Flex-T tetramer according to the manufacturer´s instructions (BioLegend). We UV-exchanged peptides for Spike epitopes restricted to HLA-A*0101 (YTNSFTRGVY), HLA-A*0201 (LITGRLQSL and RLNEVAKNL), HLA-A*2402 (NYNYLYRLF), and HLA-B*0702 (APHGVVFL) and tetramerized with Streptavidin-PE (Biolegend). A similar approach was performed for non-Spike derived epitopes, including HLA-A*0101 (ORF3a, FTSDYYQLY, and ORF1ab, TTDPSFLGRY), HLA-A*0201 (ORF3a, LLYDANYFL), HLA-A*2402 (ORF3a, VYFLQSINF), and HLA-B*0702 (Nucleoprotein, SPRWYFYYL) and tetramerized with Streptavidin-APC (Biolegend). CMV-and EBV/FLU-specific CD8 T cells were generated similarly and tetramerized using Streptavidin-PECF594 (Biolegend) and Streptavidin-PE-Cy5, respectively. CMV-derived epitopes were for HLA-A*0101 (DNA polymerase processivity factor, VTEHDTLLY), HLA-A*0201 (65 kDa phosphoprotein, NLVPMVATV), HLA-A*2402 (65 kDa phosphoprotein, QYDPVAALF), and HLA-B*0702 (65 kDa phosphoprotein, RPHERNGFTVL) and EBV derived epitopes were for HLA-A*0201 (EBV LMP2, FLYALALLL) and HLA-B*0702 (EBV antigen 3, RPPIFIRRL). A Flu peptide was for HLA-A*0101 (Nucleoprotein, Influenza A virus CTELKLSDY). All peptides were ordered from Genscript with a purity above 85% by HPLC purification and mass spectrometry. Lyophilized peptides were reconstituted at a stock concentration of 10 mM in DMSO.

Antigen-specific multimer CD8 T cells were identified by fine manual gating. The designation of bona fide antigen-specific T cells was further dependent on (a) the detection cut-off threshold ( ≥ 5 events to be detected), (b) the background noise (frequencies of specific CD8 T cells must be greater than frequencies from the corresponding CD4 T-cell population) as unbiased objective criteria for antigen-specificity assessment. Spike and non-Spike Dextramers staining have been extensively validated in COVID-19 convalescent patients and in SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated healthy donors during longitudinal follow-up. The peptides are referenced individually in the Supplementary Section.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific memory B cells

Spike-specific B cells from thawed PBMCs were detected using sequential staining of biotinylated Recombinant WT SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Trimer and RBD (HEK) (Miltenyi) conjugated with streptavidin-PE or streptavidin-BV786 respectively and combined with probes already conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 for Spike RBD B1.1, 529 (AFR11056, R&D Systems) and conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 for Full-length Spike B1.1, 529 protein (AFG11061, R&D Systems,). Commercial probes were already conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 for Spike RBD B1.1, 529 (AFR11056, Gly339Asp, Ser371Leu, Ser373Pro, Ser375Phe, Lys417Asn, Asn440Lys, Gly446Ser, Ser477Asn, Thr478Lys, Glu484Ala, Gln493Arg, Gly496Ser, Gln498Arg, Asn501Tyr, Tyr505His, R&D Systems) and conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 for Full-length Spike B1.1, 529 protein (AFG11061, Ala67Val, His69del, Val70del, Thr95Ile, Gly142Asp, Val143del, Tyr144del, Tyr145del, Asn211del, Leu212Ile, ins214Glu-Pro-Glu, Gly339Asp, Ser371Leu, Ser373Pro, Ser375Phe, Lys417Asn, Asn440Lys, Gly446Ser, Ser477Asn, Thr478Lys, Glu484Ala, Gln493Arg, Gly496Ser, Gln498Arg, Asn501Tyr, Tyr505His, Thr547Lys, Asp614Gly, His655Tyr, Asn679Lys, Pro681His, Asn764Lys, Asp796Tyr, Asn856Lys, Gln954His, Asn969Lys, Leu981Phe) (Arg682Ser, Arg685Ser, Lys986Pro, Val987Pro, R&D Systems,). 2 × 106 cryo-preserved PBMC samples were transferred in a 96-well U-bottom plate. Cells were first stained with Fc block (BD Biosciences) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed and stained with probe master mix containing 100 ng Spike-A488, and 25 ng RBD-A647 for 1 h at 4 °C. Following incubation with antigen probes, cells were washed twice and stained with Blue Live Dead (Thermo Fischer) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed again and stained with antibodies according to manufacturer protocols: BUV805-Mouse Anti-Human CD7, clone M-T701 BD Biosciences, BUV805-Mouse Anti-Human CD14, clone M5E2, BD Biosciences, BV711-Mouse Anti-Human CD19, clone HIB19, BD Biosciences, BUV395-Mouse Anti-Human CD20, clone 2H7, BD Biosciences, BUV737-Mouse Anti-Human CD21, clone B-ly4, BD Biosciences, BUV615-Mouse Anti-Human CD24, clone ML5, BD Biosciences, A700-Mouse Anti-Human CD27, clone L128, BD Biosciences, PE-CF594-Mouse Anti-Human CD38, clone HIT2, BD Biosciences, PecyPE-Cy-7-Mouse Anti-Human CD71, clone CY1G4, BD Biosciences, BV605-Mouse Anti-Human IgD, clone IA6-2, BD Biosciences, Percp.5PerCP-Cy5.5 Mouse Anti-Human IgM, clone MHM-88, Biolegend, BV421-Mouse Anti-Human IgG, clone G18-145, BD Biosciences, APC-H7-Mouse Anti-Human HLA-DR, clone L243, Biolegend, and BV480-Rat Anti-Human CXCR5, clone RF8B2, BD Biosciences for 30 min on ice. Cells stained with the Spike Trimer were fixed with the transcription factor buffer (Thermo Fischer) and intra-cellularly stained for IRF4 (eFluor660, clone 3E4, Thermo Fischer) and Blimp-1 (PE-CF594, clone 6D3, BD Biosciences). Cells stained with RBD and full Spike probes were fixed overnight in 1% PFA. Samples were acquired on BD FACSymphony.

In vitro stimulation assays

Thawed cells were stimulated for 16 h with SARS-CoV-2 PepTivator Spike and non-Spike peptides consisting of 15-mer sequences with 11 amino acid overlaps (Wuhan-Hu-1, i.e., wild-type WT. Miltenyi Biotec) as described33. In brief, thawed cells were stimulated for 16 h with SARS-CoV-2 PepTivator Spike protein peptides consisting of 15-mer sequences with 11 amino acid overlaps (Wuhan-Hu-1, i.e. wild type WT. Miltenyi Biotec) as described (1). For non-Spike (WT) responses, cells were stimulated with Nucleoprotein (PepTivator SARS-CoV-2 Prot N) and Membrane protein (PepTivator SARS-CoV-2 Prot M), consisting of 15-mer sequences with 11 amino acid overlaps in addition to the 4 ORF1ab/Orf3a peptides in Supplementary Table S7, i.e., stimulated with M + N + O. Alternatively, cells were stimulated with 88 pooled WT immunodominant oligopeptides from the whole proteome (PepTivator SARS-CoV-2 Select, Miltenyi Biotec) consisting of peptides from structural proteins (S, M, N) as well as non-structural proteins (O).

Thawed cells were also stimulated for 16 h with PepMixTM HIV-1 (Con B gag motif, JPT) consisting of a Pool of 123 peptides derived from a peptide scan (15mers with 11 aa overlap) through Con B gag motif of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

Peptide stimulation was performed on 1 million PBMCs per condition in the presence of costimulatory antibodies against CD28 and CD49d (BD Biosciences) and Brefeldin-A (10 μg/mL, Millipore Sigma). SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells were identified by dual expression of CD40L (CD154) and CD137, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) for CD4 T cells and by dual expression of IFN-γ and TNF or CD137 and IL-2, TNF or IFN-γ for CD8 T cells.

Serology

A multiplexed bead-based flow cytometry assay, referred to as microsphere affinity proteomics (MAP), was adapted for the detection of WT and VOC SARS-CoV-2 Spike and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) antibodies or anti-viral IgG antibodies (anti-EBV, anti-FLU, anti-Rhinovirus) as described91,92,93,94.

Statistics

Comparative analyses of frequencies of cell subsets and marker expression are presented by GraphPad Prism version 10.1. The difference between the control and test group was tested using the Mann–Whitney U-test for unpaired data and the Wilcoxon test on paired samples for the comparison between unstimulated and peptide-stimulated samples. Tests were two-sided. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Correlations were calculated with Pearson’s test. A correlation matrix was calculated comparing phenotypic and serological marker variables in a pairwise fashion, using the corr. test function from the psych CRAN package; the corrplot package was subsequently used to graphically display the correlation matrix. The resulting p-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Bonferroni method. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were indicated by a heat scale, whereby the red color shows a positive linear correlation, and the blue color shows a negative linear correlation. The volcano plots and the correlation matrix were integrated as a package in CYTOGRAPHER®, ImmunoScape cloud-based analytical software. The SPICE (Simplified presentation of incredible complex evaluations) software was used to determine the polyfunctionality of antigen-specific T cells. A permutation test from SPICE software was used to compare the distribution of cell populations for each pair of pie charts. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Sample availability

The patient samples are not available on request due to restricting ethical and legal approvals.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abrams, E. M. & Szefler, S. J. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 659–661 (2020).

Cavanna, L., Citterio, C. & Toscani, I. COVID-19 vaccines in cancer patients. Seropositivity and safety. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9091048 (2021).

Galmiche, S. et al. Immunological and clinical efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised populations: a systematic review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 28, 163–177 (2022).

Gao, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, M., Shi, S. & Tian, J. Impacts of immunosuppression and immunodeficiency on COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 81, e93–e95 (2020).

Gustafson, C. E., Kim, C., Weyand, C. M. & Goronzy, J. J. Influence of immune aging on vaccine responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 145, 1309–1321 (2020).

Jedicke, N. et al. Humoral immune response following prime and boost BNT162b2 vaccination in people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 23, 558–563 (2022).

Kared, H. et al. Hybrid and SARS-CoV-2-vaccine immunity in kidney transplant recipients. EBioMedicine 97, 104833 (2023).

Notarte, K. I. et al. Effects of age, sex, serostatus, and underlying comorbidities on humoral response post-SARS-CoV-2 Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccination: a systematic review. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 59, 373–390 (2022).

Hoft, M. A., Burgers, W. A. & Riou, C. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in people with HIV. Cell Mol. Immunol. 21, 184–196 (2024).

Hanson, H. A., Kim, E. & Badowski, M. E. A systematic review: impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on morbidity, mortality, and viral suppression in patients living with HIV. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 5, 144 (2023).

Engsig, F. N. et al. Long-term mortality in HIV-positive individuals virally suppressed for >3 years with incomplete CD4 recovery. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 1312–1321 (2014).

Pacheco, Y. M. et al. Increased risk of non-AIDS-related events in HIV subjects with persistent low CD4 counts despite cART in the CoRIS cohort. Antivir. Res. 117, 69–74 (2015).

Yan, L. et al. Cellular and molecular insights into incomplete immune recovery in HIV/AIDS patients. Front. Immunol. 14, 1152951 (2023).

Deeks, S. G. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 62, 141–155 (2011).

Moir, S. & Fauci, A. S. B-cell responses to HIV infection. Immunol. Rev. 275, 33–48 (2017).

Dandachi, D. et al. Characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes in a multicenter registry of patients with human immunodeficiency virus and coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, e1964–e1972 (2021).

Kassanjee, R. et al. COVID-19 among adults living with HIV: correlates of mortality among public sector healthcare users in Western Cape, South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 26, e26104 (2023).

Tesoriero, J. M. et al. COVID-19 outcomes among persons living with or without diagnosed HIV infection in New York state. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2037069 (2021).

Wit, F. et al. COVID-19 in people with HIV in the Netherlands. AIDS 37, 1671–1681 (2023).

Yang, X. et al. Associations between HIV infection and clinical spectrum of COVID-19: a population level analysis based on US National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) data. Lancet HIV 8, e690–e700 (2021).

Russell, C. D., Lone, N. I. & Baillie, J. K. Comorbidities, multimorbidity and COVID-19. Nat. Med. 29, 334–343 (2023).

Cossu, M. V. et al. Comorbidity burden and suboptimal immunological responses to coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in people living with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 227, 733–735 (2023).

Verburgh, M. L. et al. Robust vaccine-induced as well as hybrid B- and T-Cell immunity across SARS-CoV-2 vaccine platforms in people with HIV. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0115523 (2023).

El Chaer, F. & El Sahly, H. M. Vaccination in the adult patient infected with HIV: a review of vaccine efficacy and immunogenicity. Am. J. Med. 132, 437–446 (2019).

Remschmidt, C., Wichmann, O. & Harder, T. Influenza vaccination in HIV-infected individuals: systematic review and assessment of quality of evidence related to vaccine efficacy, effectiveness and safety. Vaccine 32, 5585–5592 (2014).

Tortellini, E. et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccination in people living with human immunodeficiency virus. Viruses 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/v15091844 (2023).

Brenchley, J. M. & Douek, D. C. HIV infection and the gastrointestinal immune system. Mucosal Immunol. 1, 23–30 (2008).

Zicari, S. et al. Immune activation, inflammation, and non-AIDS co-morbidities in HIV-infected patients under long-term ART. Viruses 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/v11030200 (2019).

Ciabattini, A. et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2-specific memory B cells six months after vaccination with the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. Front. Immunol. 12, 740708 (2021).

Goel, R. R. et al. mRNA vaccines induce durable immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Science 374, abm0829 (2021).

Notarte, K. I. et al. Characterization of the significant decline in humoral immune response six months post-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination: a systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 94, 2939–2961 (2022).

Del Valle, D. M. et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat. Med. 26, 1636–1643 (2020).

Kared, H. et al. Immune responses in Omicron SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection in vaccinated adults. Nat. Commun. 13, 4165 (2022).

Doni, A. et al. The long pentraxin PTX3 as a link between innate immunity, tissue remodeling, and cancer. Front. Immunol. 10, 712 (2019).

Garred, P. et al. Susceptibility to HIV infection and progression of AIDS in relation to variant alleles of mannose-binding lectin. Lancet 349, 236–240 (1997).

Khoury, D. S. et al. Correlates of protection, thresholds of protection, and immunobridging among persons with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 381–388 (2023).

Coburn, S. B. et al. Analysis of postvaccination breakthrough COVID-19 infections among adults with HIV in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2215934 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Association between immune dysfunction and COVID-19 breakthrough infection After SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the US. JAMA Intern. Med. 182, 153–162 (2022).

Lane, H. C. et al. Abnormalities of B-cell activation and immunoregulation in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 309, 453–458 (1983).

Zhou, Q. et al. Correlation between CD4 T-cell counts and seroconversion among COVID-19 vaccinated patients with HIV: a meta-analysis. Vaccines 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11040789 (2023).

Tuan, J. J. et al. Qualitative assessment of anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein immunogenicity (QUASI) after COVID-19 vaccination in older people living with HIV. HIV Med. 23, 178–185 (2022).

Brockman, M. A. et al. Reduced magnitude and durability of humoral immune responses to COVID-19 mRNA vaccines among older adults. J. Infect. Dis. 225, 1129–1140 (2022).

Costiniuk, C. T. et al. COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity in people with HIV. AIDS 37, F1–F10 (2023).

Heftdal, L. D. et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses eleven months after the third dose of BNT162b2 an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine in people with HIV - a prospective observational cohort study. EBioMedicine 93, 104661 (2023).

Levy, I. & Rahav, G. The effect of HIV on COVID-19 vaccine responses. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 18, 135–141 (2023).

Thorley-Lawson, D. A. & Gross, A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med 350, 1328–1337 (2004).

Whitehurst, C. B. et al. HIV co-infection augments EBV-induced tumorigenesis in vivo. Front. Virol. 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/fviro.2022.861628 (2022).

Ho, J. et al. Two overrepresented B cell populations in HIV-infected individuals undergo apoptosis by different mechanisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19436–19441 (2006).

Suryani, S. et al. Differential expression of CD21 identifies developmentally and functionally distinct subsets of human transitional B cells. Blood 115, 519–529 (2010).

Malaspina, A. et al. Appearance of immature/transitional B cells in HIV-infected individuals with advanced disease: correlation with increased IL-7. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2262–2267 (2006).

Estes, J. D. Pathobiology of HIV/SIV-associated changes in secondary lymphoid tissues. Immunol. Rev. 254, 65–77 (2013).

Levin, E. G. et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine over 6 months. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, e84 (2021).

Perez-Alos, L. et al. Modeling of waning immunity after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and influencing factors. Nat. Commun. 13, 1614 (2022).

Cao, Y. et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature 602, 657–663 (2022).

Karim, S. S. A. & Karim, Q. A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 2126–2128 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 602, 676–681 (2022).

Mlcochova, P. et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 Delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature 599, 114–119 (2021).

Planas, D. et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature 596, 276–280 (2021).

Vergori, A. et al. Immunogenicity to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine third dose in people living with HIV. Nat. Commun. 13, 4922 (2022).

Vergori, A. et al. Neutralizing activity and T-cell response after bivalent fifth dose of messenger RNA vaccine in people living with HIV. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 134, 195–199 (2023).

Alrubayyi, A. et al. Characterization of humoral and SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell responses in people living with HIV. Nat. Commun. 12, 5839 (2021).

Donadeu, L. et al. Long-lasting adaptive immune memory specific to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent coronavirus disease 2019 stable people with HIV. AIDS 36, 1373–1382 (2022).

Peluso, M. J. et al. Postacute sequelae and adaptive immune responses in people with HIV recovering from SARS-COV-2 infection. AIDS 36, F7–F16 (2022).

Riou, C. et al. Relationship of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 response to COVID-19 severity and impact of HIV-1 and tuberculosis coinfection. J. Clin. Invest. 131, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI149125 (2021).

Feng, Y. et al. Immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in people living with HIV-1: a non-randomized cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 43, 101226 (2022).

Frater, J. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in HIV infection: a single-arm substudy of a phase 2/3 clinical trial. Lancet HIV 8, e474–e485 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Comparing immune responses to inactivated vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 between people living with HIV and HIV-negative individuals: a cross-sectional study in China. Viruses 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/v14020277 (2022).

Oyaert, M. et al. Evaluation of humoral and cellular responses in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinated immunocompromised patients. Front. Immunol. 13, 858399 (2022).

Woldemeskel, B. A. et al. The BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine elicits robust humoral and cellular immune responses in people living with human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Clin. Infect. Dis. 74, 1268–1270 (2022).

Antinori, A. et al. Humoral and cellular immune response elicited by mRNA vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in people living with human immunodeficiency virus receiving antiretroviral therapy based on current CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, e552–e563 (2022).

Keeton, R. et al. T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike cross-recognize Omicron. Nature 603, 488–492 (2022).

Redd, A. D. et al. Minimal crossover between mutations associated with Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 and CD8(+) T-cell epitopes identified in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. mBio 13, e0361721 (2022).

Redd, A. D. et al. CD8+ T-cell responses in COVID-19 convalescent individuals target conserved epitopes from multiple prominent SARS-CoV-2 circulating variants. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 8, ofab143 (2021).

Tarke, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination induces immunological T cell memory able to cross-recognize variants from Alpha to Omicron. Cell 185, 847–859.e811 (2022).

Moss, P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Immunol. 23, 186–193 (2022).

Mallajosyula, V. et al. CD8(+) T cells specific for conserved coronavirus epitopes correlate with milder disease in COVID-19 patients. Sci. Immunol. 6, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abg5669 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. An immunodominant NP(105-113)-B*07:02 cytotoxic T cell response controls viral replication and is associated with less severe COVID-19 disease. Nat. Immunol. 23, 50–61 (2022).

Naranbhai, V. et al. T cell reactivity to the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is preserved in most but not all individuals. Cell 185, 1041–1051.e1046 (2022).

Nemet, I. et al. Third BNT162b2 vaccination neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 492–494 (2022).

Suryawanshi, R. K. et al. Limited cross-variant immunity from SARS-CoV-2 Omicron without vaccination. Nature 607, 351–355 (2022).

Agrati, C. et al. Persistent spike-specific T cell immunity despite antibody reduction after 3 months from SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2-mRNA vaccine. Sci. Rep. 12, 6687 (2022).

Gao, F. et al. Spheromers reveal robust T cell responses to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine and attenuated peripheral CD8(+) T cell responses post SARS-CoV-2 infection. Immunity 56, 864–878.e864 (2023).

Korencak, M. et al. Effect of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy on immune cellular functions. JCI Insight 4, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.126675 (2019).

Maslo, C. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients in South Africa during the COVID-19 Omicron wave compared with previous waves. JAMA 327, 583–584 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Characterizing distinct profiles of immune and inflammatory response with age to Omicron infection. Front. Immunol. 14, 1189482 (2023).

Campbell, J. H., Hearps, A. C., Martin, G. E., Williams, K. C. & Crowe, S. M. The importance of monocytes and macrophages in HIV pathogenesis, treatment, and cure. AIDS 28, 2175–2187 (2014).

Msomi, N., Lessells, R., Mlisana, K. & de Oliveira, T. Africa: tackle HIV and COVID-19 together. Nature 600, 33–36 (2021).

Karim, F. et al. Clearance of persistent SARS-CoV-2 associates with increased neutralizing antibodies in advanced HIV disease post-ART initiation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2360 (2024).

Peluso, M. J., Bakkour, S., Busch, M. P., Deeks, S. G. & Henrich, T. J. A high percentage of people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) on antiretroviral therapy experience detectable low-level plasma HIV-1 RNA following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, e2845–e2846 (2021).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801–810 (2016).

Holter, J. C. et al. Systemic complement activation is associated with respiratory failure in COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 25018–25025 (2020).

Jyssum, I. et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses to two and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in rituximab-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective, cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 4, e177–e187 (2022).

Sikorski, K. et al. A high-throughput pipeline for validation of antibodies. Nat. Methods 15, 909–912 (2018).

Wu, W. et al. Antibody array analysis with label-based detection and resolution of protein size. Mol. Cell Proteom. 8, 245–257 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by CEPI and received support from KG Jebsen Centre for B-cell malignancies (grant 19), The Health South East Health Authority, the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence scheme, project number 332727, Oslo University Hospital, and the University of Oslo. Funders have no role in the design and writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K. and L.A.M. conceived and designed the study. H.K. and L.A.M. drafted the paper. A.D.R., J.C.H., D.H.R., F.L.J., B.H., C.P., T.B., and A.A. contributed to drafting the paper. H.K., A.A., I.E., and A.C. performed experiments. H.K., A.A., I.E., and L.A.M., analyzed and interpreted data. A.A., I.E., A.C., T.B., F.L.J., and A.D.R. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. L.S., T.B., C.P., K.T., D.H.R., B.S., J.T.V., B.H., J.C.H., and A.D.R. organized the collection of samples and information from the cohorts. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alirezaylavasani, A., Skeie, L.G., Egner, I.M. et al. Vaccine responses and hybrid immunity in people living with HIV after SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections. npj Vaccines 9, 185 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00972-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00972-3

This article is cited by

-

Booster dose reshapes SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific B cell immunity in people living with HIV

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)