Abstract

RTS,S/AS01E, the first approved malaria vaccine, demonstrated moderate efficacy during the phase 3 pediatric trial. We previously investigated cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses following the primary 3-dose immunization and now report responses to the booster dose given 18 months later. Thirty CMI markers were measured by Luminex in supernatants of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 709 children and infants after RTS,S/AS01E antigen stimulation, and their associations with malaria risk and antibodies one month post-booster and one year later were assessed. IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-5, and IL-13 were associated with RTS,S/AS01E booster vaccination, and IL-2 responses to the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) remained higher after one year. IL-2 was associated with reduced malaria risk in one site, and IL-10 was associated with increased risk in infants. Anti-CSP IgG and IL-2 were moderately correlated one year after booster. This study highlights the moderate cell-mediated immunogenicity of the RTS,S/AS01E booster dose that aligns with partial recovery of RTS,S/AS01E vaccine efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The decades-long effort to develop a malaria vaccine reached a historic achievement in 2021, when RTS,S/AS01E (RTS,S), the first malaria vaccine to pass a pediatric phase 3 clinical trial, was recommended by the World Health Organization for use in children living in regions with moderate-to-high malaria transmission1. The pre-erythrocytic RTS,S vaccine contains a portion of the central repeating amino acid sequence NANP and the C-terminal region of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP), fused to and co-expressed with unfused hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and formulated with AS01E, a liposomal-based adjuvant containing Monophosphoryl lipid A and QS-212. RTS,S was designed to generate strong humoral and cell-mediated immunity3; nevertheless, identifying RTS,S immune correlates of protection has been an ongoing challenge4.

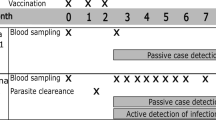

The phase 3 trial consisted of a 3-dose primary immunization regimen (month [M] 0, M1, and M2) followed by a booster dose at M20. The antibody type and levels generated by RTS,S primary vaccination towards CSP have demonstrated a correlation with protection in children during the phase 3 trial5,6,7. While the booster dose restored vaccine efficacy8 from 18.3 to 25.9% in infants and 28.3 to 36.3% in children, unexpectedly, IgG antibody levels to the NANP repeat region of CSP post-booster were lower compared to the response post-primary vaccination5,9. B cell responses are likely supported by CD4+ T cells; therefore, understanding the role of RTS,S-induced cellular responses in generating and maintaining antibodies is essential.

RTS,S studies using controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) of malaria-naïve adults10,11,12 or in field studies with children13,14,15,16 have made some advances toward understanding RTS,S-induced cellular responses. However, the association of cell responses with malaria protection, as well as the underlying mechanisms, remains unclear17. CSP-specific CD4+ T cells appear to be consistently associated with RTS,S, specifically with the expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) identified during RTS,S phase 2 trials11,13,14,15,18. In children following primary vaccination during the RTS,S phase 3 trial, we detected higher frequencies of CSP- and HBsAg-specific central memory and effector memory CD4+ T cells co-expressing IL-2, TNF and the co-stimulatory molecule CD40L, as well as HBsAg-specific CD4+ T cells producing interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-17, and effector memory CD4+ T cells producing IL-21, a T follicular helper (TFH) cytokine, to both vaccine antigens19. In a CHMI study in malaria naïve adults, RTS,S also induced TFH cells producing IL-21, which were associated with protection20. In the RTS,S phase 3 clinical trial, following in vitro stimulations of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with vaccine antigens, we found primary RTS,S vaccination to be associated with CSP-specific IL-2 and IL-5 secretion. TH1 cytokines, particularly IFN-γ, IL-15, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), correlated with malaria protection, while TH2 cytokines IL-5 and regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), were associated with risk16.

No data exists for RTS,S-induced cellular immune responses following the booster dose during the pediatric phase 3 trial. Our study aimed to assess the vaccine-specific cytokine, chemokine and growth factor responses at M21 following the RTS,S booster dose, and the maintenance one year later at M32, in two African sites, which is an essential step towards filling this gap. We evaluated associations between the markers and the risk of malaria 11 months later, and considered the effect of epidemiological and clinical factors and previous malaria episodes on the response to the booster dose. Additionally, we explored associations of cytokine responses with RTS,S-induced antibodies after the booster dose. Identifying factors associated with RTS,S immunogenicity and protective cellular responses is critical to designing effective, longer-lasting, second-generation malaria vaccines.

Results

Study population

At M21, a total of 709 infants and children from Bagamoyo, Tanzania, and Manhiça, Mozambique, were analyzed between the three vaccine groups that either received the RTS,S booster (R3R) or comparator vaccine (R3C and C3C) at M20 (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). The median age was 26.7 months, and approximately 52% of participants were female. Previous malaria cases within 1-year before M20 occurred in 6.6% of participants; hemoglobin concentrations measured at M20 showed that 29.5% of the participants had anemia ( < 10 g/dL), and 6.2% were malnourished according to weigh-for-age Z-scores (WAZ score <−2).

Immunogenicity of the RTS,S booster dose at M21 and M32

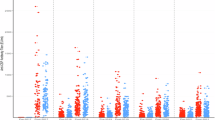

To identify markers of immunogenicity elicited by the RTS,S booster dose, we compared vaccine antigen cytokine concentration ratios from R3R (RTS,S-boosted) versus R3C (RTS,S-unboosted) and R3R versus C3C (Comparator) at M21 and M32. At M21, CSP and HBsAg ratios were significantly higher for IL-2 in the R3R group compared to the C3C group (Fig. 1a) whereas the increase relative to the R3C group was not statistically significant. CSP-stimulated IL-13 ratios were also higher in the R3R compared to the C3C group but not statistically significant after adjustment for multiple testing (P = 0.007, Padj = 0.07). In addition, HBsAg-stimulated cytokine ratios were also significantly higher for IFN-γ, IL-5, and IL-13 in R3R than in C3C, and the booster dose was found to significantly increase IL-17 in the R3R group compared to both R3C and C3C (Fig. 1a). At M32, CSP responses were maintained for IL-2, which were significantly higher in R3R compared to both R3C and C3C; and HBsAg ratios were higher for IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-5 in the R3R compared to the C3C group (Fig. 1a).

a Forest plots illustrating fold differences in geometric mean relative concentrations between vaccine groups for all cytokines, one month following the booster at M21 (left) and one year later at M32 (right). Point estimates and whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals (CI); asterisks (*) indicate significant differences in distributions according to Wilcoxon tests after Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment. b Boxplots showing individual levels and comparing vaccination groups for the five markers that were significantly increased upon vaccination for either CSP- and/or HBsAg-stimulated PBMC samples. The central line in the box represents the median of the relative concentrations in each vaccination group, while the box limits indicate the quartiles.

Box plots displaying individual data points for the primary immunogenicity markers IL-2, IL-13, IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-5 show an increasing trend for R3C (RTS,S-unboosted) and R3R (RTS,S-boosted) over C3C (Comparator) for both CSP and HBsAg ratios at M21 and M32 (Fig. 1b). Analysis of crude concentrations showed a similar pattern of significantly elevated cytokines following CSP and HBsAg stimulation as was found for the antigen ratios (Supplementary Fig. 2). Correlations between levels of CSP-stimulated versus HBsAg-stimulated primary immunogenicity markers assessed at M21 showed low to moderate positive correlations between the two vaccine antigens in all three vaccine groups (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Factors affecting RTS,S immunogenicity at M21 and M32

To evaluate if there were clinical or demographic factors affecting the above RTS,S immunogenicity markers (IL-2, IL-13, IFN-γ, IL-17 or IL-5), we analyzed the effect modification of age, sex, site, previous malaria exposure, anemia, and WAZ scores on the cytokine increases in R3R (RTS,S-boosted) versus C3C (Comparator) group (Fig. 2). At M21, no statistically significant effect modification by any condition on immunogenicity markers was observed (interaction Padj > 0.05). However, unadjusted analysis showed that age and site were effect modifiers of vaccination immunogenicity, specifically for CSP-specific IL-5 for age (interaction P = 0.02; Padj = 0.32) and IFN-γ (interaction P = 0.005; Padj = 0.14), and IL-17 (interaction P = 0.02; Padj = 0.32) for site (Fig. 2). In stratified analyses, CSP-specific IL-13, IFN-γ, and IL-17 were associated with RTS,S booster for children (P = 0.03, P = 0.006, P = 0.02, respectively) but not for infants (P = 0.78, P = 0.9, P = 0.33, respectively), who had increased CSP-specific IL-5 by vaccination (P = 0.02) (Fig. 2). For HBsAg stimulation, age was an effect modifier of vaccination on IL-17 and IL-13 responses (RTS,S booster induced IL-17 and IL-13 in children but not in infants), although the interaction was not statistically significant after adjustment for multiple testing (interaction P = 0.003; Padj = 0.14 and P = 0.006; Padj = 0.14, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Forest plots illustrating fold differences in geometric mean relative concentrations (ratios) of CSP- and HBsAg-stimulated cytokine responses between R3R (RTS,S-boosted) and C3C (Comparator) groups stratified by age, sex, site, prior malaria exposure (1-year before M20), anemia, and WAZ scores, for the primary RTS,S immunogenicity markers (IL-2, IL-13, IFN-γ, IL-17 or IL-5). Open and closed diamonds representing conditions within each factor are defined in the bottom panel showing sample size. Point estimates and whiskers indicate 95% CI. No significant effect modification (interaction) in a regression model was found following Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment. Bar plots representing the number of study participants within each group are shown at the bottom.

At M32, no immunogenicity effect modifiers were identified for CSP stimulations (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, age and site were associated with significantly different RTS,S-induced HBsAg IL-2 responses (Supplementary Fig. 4), though significance was lost after adjusting for multiple comparisons. RTS,S booster dose induced higher IL-2 concentrations in infants than children at M32 (interaction P = 0.006, Padj = 0.16) and higher in Bagamoyo than Manhiça (interaction P = 0.007; Padj = 0.17).

Malaria exposure before M21 was not associated with CSP-specific responses in non-vaccinated participants (C3C), suggesting absence of naturally acquired immunity for CSP cellular responses (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Correlates of malaria risk

The association of the main immunogenicity markers at M21 with the risk of malaria during the following 11 months was assessed through Cox models including the interaction with vaccination group (Fig. 3a). None of the CSP and HBsAg primary immunogenicity markers were associated with risk of malaria between the different vaccine groups (interaction), nor was there a direct association within any of these groups (stratified association) (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 6). For the other markers, CSP-stimulated RANTES showed a tendency towards increasing malaria risk with more RTS,S vaccination (interaction P = 0.02, Padj = 0.5) (Supplementary Fig. 6). For CSP, no association was found for any marker with malaria regardless of the vaccine group (main effect).

Hazard ratios indicate the factor by which the hazard is estimated to increase or decrease for one standard deviation change in the cytokine relative concentrations (ratio). Association of the primary immunogenicity markers with hazard of malaria in (a) children and infants together; (b) children only; and (c) infants only. Significance was tested with a Wald test on the corresponding Cox regression coefficient used to obtain hazard ratios. No significant differences were found following Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment.

For HBsAg responses, increased IL-10, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-1α) and TNF levels in R3R (RTS,S-boosted) showed tendencies for lower risk of malaria (P = 0.045 and P = 0.040 and P = 0.072, respectively) but were not significant after adjustment. HBsAg-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1) was significantly associated with lower risk of malaria for main effect (regardless of vaccine group), though significance was lost after adjustment (P = 0.01; Padj = 0.160) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Factors affecting correlates of malaria risk

In stratified analyses by age cohort (Fig. 3b, c; Supplementary Fig. 7a, b), in infants and the R3C (RTS,S-unboosted) group, CSP IL-2 was associated with risk of malaria (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 3.3, confidence intervals (CI) [1.3, 8.2]), but this was not significant when adjusting for multiple comparisons (P = 0.009, Padj = 0.5) and CI were very wide (Fig. 3c). Likewise, in R3C for HBsAg, IL-2 and IL-13 were associated with increased risk of malaria, but significance was lost after adjustment (P = 0.01, Padj = 0.5; P = 0.02, Padj = 0.6, respectively) (Fig. 3c). For infants, IL-10 was significantly associated with a higher risk of malaria regardless of vaccination (main effect P = 0.0005, Padj = 0.02), an effect that also reached unadjusted significance in the R3R (RTS,S-boosted) group (P = 0.02, Padj = 0.5) (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

Stratified correlates analysis by site showed a significant effect modification of CSP-stimulated IL-2 on the risk of malaria by the different vaccination groups in Manhiça before adjusting for multiple comparisons (interaction P = 0.02, Padj = 0.8), with a stronger association with lower risk in the R3R (RTS,S-boosted) group, but not in Bagamoyo (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). In line with these observations, CSP-specific IL-2 levels were higher in controls than malaria cases in the R3R group in Manhiça (unadjusted P = 0.0356) (Supplementary Fig. 8c), whereas there were no differences in Bagamoyo (P = 0.597). No other primary immunogenicity markers were found to have significant associations with malaria risk for either vaccine antigen in either of the two sites (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b).

Correlation between RTS,S-induced cytokines and antibody responses at M21 and M32

For total anti-CSP NANP IgG antibody levels measured by ELISA, no statistically significant correlations were found with any of the primary immunogenicity markers at M21 (Fig. 4a); however, a significant inverse correlation of RANTES with anti-CSP IgG was observed (Fig. 4b). Total anti-CSP NANP IgG had a significant moderate positive correlation with IL-2 at M32 (Fig. 4c).

a Primary immunogenicity markers measured at M21, (b) RANTES measured at M21, and (c) primary markers measured at M32. Antibody levels shown as EU/mL and cytokines as log10 ratios. Spearman rho and P-values are shown in the plots with a linear regression trend line. R3R (RTS,S-boosted) and R3C (RTS,S-unboosted) have been pooled, n = 30 at M21 and n = 28 at M32.

Further correlations were performed using anti-CSP full length (CSP FL), anti-NANP, and anti-C-terminus (Cterm) IgG subclass levels measured by Luminex in a previous study showing that the booster dose induced IgG, IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4, but not IgG2, which had relatively unchanged levels following the primary vaccination until M32. At M21, for the primary immunogenicity markers, we only observed a significant moderate positive correlation for IL-17 with anti-NANP IgG2 levels (Supplementary Fig. 9a). IL-15 had a moderate significant inverse correlation with anti-CSP FL IgG4 at M21 (Supplementary Fig. 9b). At M32, a significant moderate inverse correlation was found for IL-2 and IL-13 with anti-NANP IgG2, and IL-2 and IL-5 with IgG4 (Supplementary Fig. 9c, d). For the remaining primary markers and IgG subclasses against CSP antigens, there were no significant correlations (Supplementary Fig. 10). RANTES had moderate significant positive correlations with anti-CSP FL and Cterm IgG and IgG1, and anti-NANP IgG4 at M32 (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Regarding HBsAg cytokine responses at M21, IL-17 had significant moderate positive correlations with HBsAg IgG1, and IL-2, IL-5 and IL-13 with IgG2 (Supplementary Fig. 12). At M32, positive correlations were found between IL-17, IL-5, and IL-13 with anti-HBsAg IgG and IgG1, also IL-17 and IL-5 with IgG2, and IL-5 with IgG4 (Supplementary Fig. 13). Additionally, some HBsAg-specific cytokine concentrations correlated positively with CSP antibodies at M21, mainly involving IL-17 and IL-2 responses correlating with protective IgG1 and IgG3 against the CSP FL and NANP (Supplementary Figs. 14, 15) and IL-17, IL-5 and IL-13 correlating with Cterm IgG3, and IL-17 with Cterm IgG1 (Supplementary Figs. 16). At M32, fewer significant correlations between HBsAg-specific cytokine responses and CSP antibodies were found (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Discussion

The RTS,S fourth dose in the African pediatric phase 3 trial significantly increased levels of CSP-specific IL-2 one month post-booster and, importantly, it remained elevated one year after. However, significant differences in cytokine levels one month post-booster were only detected when compared with comparator vaccinees and not with RTS,S vaccinees without RTS,S booster, suggesting a modest cellular response may have been generated by the booster dose. This is in line with the limited recovery of vaccine efficacy and limited antibody induction by the booster dose. HBsAg-specific responses included more cytokines besides IL-2 (TH1), encompassing different functions: TH1 (IFN-γ), TH17 (IL-17), and TH2 (IL-13, and IL-5). IL-17 was the sole cytokine that significantly increased as a result of the booster dose compared to RTS,S vaccinated children without the RTS,S booster. Of those responses, IL-2 and IL-5 were still detected one year after the booster, indicating maintenance of some T cell memory responses. This confirms our previous results after primary vaccination that the HBsAg component of RTS,S may result in higher cellular immunogenicity than CSP, perhaps from the higher proportion of HBsAg than CSP antigen in RTS,S or due to previous hepatitis B vaccination included in the expanded program on immunization.

Despite RTS,S induction of IL-2, no clear association of this cytokine with malaria risk was detected in overall RTS,S vaccinees. However, stratifying by site, CSP-specific IL-2 in the RTS,S-boosted group tended to lower the risk of malaria in Manhiça, but not Bagamoyo, suggesting that site may affect the immune response to RTS,S vaccination and its role in protection. A previous study comparing children from Tanzania and Mozambique during the phase 3 trial found differences in immune development between the sites. Children from Tanzania had significantly lower frequencies of circulating innate and adaptive cell populations, including T cell subsets, which are the producers of IL-2, as well as effector cells potentially involved in RTS,S protective mechanisms (NK cells, monocytes, memory B and T cells)21. In contrast, stratifying the correlates analysis by age cohort, infants showed trends for CSP-specific IL-2 to be associated with a higher risk of malaria in the RTS,S-unboosted group. Nevertheless, the infant cohort had fewer overall participants in this study. Additionally, the infant cohort tended to produce lower levels of cytokines, which resulted in many markers below one after correcting for DMSO background, and yielded wide confidence intervals.

CSP-specific IL-2 has been highlighted in past RTS,S field studies as a key immunogenicity marker13,14,15,16,18,19,22,23. Still, it has only been shown to play a role in protective immunity in a study of vaccinated malaria-naïve adults12. Our previous studies following primary immunization at M3 found increased frequencies of CSP-specific IL-2 expressing CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry, and IL-2 measured in PBMC culture supernatants by Luminex; however, association with malaria protection was not observed either16,19. Yet, IL-2 may still contribute to RTS,S-induced protection, as it can stimulate proliferation, augment effector functions of T cells, and support memory CD4+ T cell populations24,25. NK cells producing IFN-γ via activation by CSP-specific CD4+ T expressing IL-2 have also been demonstrated in RTS,S-vaccinated children in Tanzania23.

Furthermore, IL-2 is key in supporting CD4+ T cell and B cell responses, which help support antibody production25. IL-2 has been demonstrated to be associated with B cell differentiation into plasma cells and the maintenance of antibody titers26,27. We found that IL-2 had a low positive correlation with anti-CSP IgG one month post-booster in RTS,S vaccinated children, with and without booster dose. However, positive correlation strength and significance increased at M32. Interestingly, there were significant moderate inverse correlations of IL-2 with anti-NANP IgG2 and IgG4. Our group previously showed IgG2 and IgG4 responses to vaccine antigens at M3 to associate with malaria risk over the one-year follow-up post-primary immunization6. Of note, the booster dose induced IgG4 (and IgG1 and IgG3) but not IgG29.

Demographic factors can impact RTS,S immunogenicity at primary vaccination, including age, geographic location, previous exposure to malaria, anemia, and health status5,6,16,21. Here, no clear-cut effect modifications were detected, although there were some tendencies at M21 of children responding with higher antigen-specific cytokines to booster vaccination (mainly IL-17, but also IL-13 and IFN-γ). Instead, infants had increased IL-5 responses after booster vaccination compared to children. Age cohort differences could be due to differences in immune composition and response according to age, but also could be a consequence of differences in primary vaccine responses.

Interestingly, the correlates analysis for infants showed IL-10, an immunoregulatory cytokine, to be significantly associated with an increased risk of malaria independently of vaccination. Elevated IL-10 has been shown in a previous study of Tanzanian children to be associated with a lower capacity to clear P. falciparum parasites28. An earlier prospective study by our group involving Mozambican mothers and their children demonstrated that higher IL-10 production was associated with a greater risk of clinical malaria, and the increased risk could be inherited29.

In our previous study on RTS,S post-primary immunization16, RANTES was also associated with malaria risk. RANTES, produced by memory T cells, monocytes, and macrophages in PBMCs30,31 can polarize cellular responses towards a TH1 profile, leading to lower antigen-specific humoral responses32, which may explain the inverse correlation that we observed between RANTES and anti-CSP IgG at M21. Acute malaria has also been shown to drive TH1 cytokine responses, resulting in a less functional TH1-polarized subset of TFH cells33. These TH1-type TFH cells were associated with impaired B cells producing suboptimal antibody responses33.

A limitation of the study is that we could not ascertain the cell origin of the RTS,S induced cytokines or if these were due to increased numbers of stimulated cells producing cytokines or rather a result of few primed cells producing higher levels of cytokines. However, previous flow cytometry studies can allow us to infer what cells may produce these cytokines. For instance, CSP-specific CD4+ T cells produced weak or no IFN-γ, while HBsAg-stimulated CD4+ T cells did14,19, and other cells produce IFN-γ after bystander stimulation23. Furthermore, IL-2 is induced mainly in activated T cells, and we know from previous studies that RTS,S increases the frequencies of CD4+ T cells producing IL-213,14,18,19,22. Characterization of T cell-specific responses by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry will be explored in future studies. These studies will inform upon the effect of the booster dose on memory and TFH cells among other cell subsets, which are critical for germinal center responses and supporting B cells for the production of high-affinity antibodies, as well as the role of RANTES on TFH cells. Another limitation inherent to malaria field trials is that participants without clinical malaria may not have been necessarily protected as they may not have been exposed (bitten by an infectious mosquito), or they may have been infected but asymptomatically or not gone to a health post even if sick. In addition, we tested all available samples, yet the sample size still limited the statistical power of our analyses of immune correlates of malaria risk. However, several cytokines were associated with malaria risk in exploratory and unadjusted analyses, which may be chance findings. Despite controlling for FDR ( < 5%), our exploratory study contains numerous comparisons, opening the possibility of false positives and therefore unadjusted associations with malaria risk have not been highlighted. Unfortunately, antibody data were only available in a subset of participants, limiting correlation analyses between antibodies and cytokines. Furthermore, the distribution of age cohorts between sites was unequal. Manhiça consisted of children and infants, while Bagamoyo only had children, which reduced the power of the effect modification analysis since we limited the site analysis to only children, and age analysis to participants only from Manhiça. New results should help generate new hypotheses but also require further independent validation.

In summary, our results further support IL-2 as a key RTS,S-induced CSP-specific immunogenicity marker that tends to associate with reduced risk of malaria and to correlate positively with anti-CSP total IgG antibody and negatively with IgG subclasses associated with increased risk. The stronger association of IL-2 with reduced risk of malaria in Manhiça compared to Bagamoyo suggests that there may be site-specific differences in RTS,S-protective responses. CSP-specific IL-10 was significantly associated with an increased risk of malaria in the infants, suggesting that this immunoregulatory cytokine should be analyzed in malaria vaccine studies. HBsAg-specific responses were more numerous than CSP, and several tendencies were found for lower risk of malaria, highlighting the need to better understand the role of HBsAg in RTS,S vaccination. Our findings align with previous studies indicating that a strong vaccine-induced IL-2 response likely provides the support necessary for a robust humoral and cellular response to control a pre-erythrocytic infection. However, RTS,S induced a relatively low IL-2 response overall that was undetected in many participants. Therefore, modifying the vaccine design and strategy to elicit a higher memory T cell response may increase vaccine durability and efficacy.

Materials and methods

Ethics

Parents or guardians of the study participants provided written informed consent. The following ethics review boards and regulatory authorities from participating countries approved the study protocol: The Ethical Committee of the Hospital Clínic in Barcelona (CEIC, Spain), National Health and Bioethics Committee (CNBS, Mozambique), Ethikkommission Beider Basel (EKBB, Switzerland), National Institutional Review Board (NIMR, Tanzania), Ifakara Health Institute IRB (IHIIRB, Tanzania), and the Research Ethics Committee (REC, USA).

Study Design

This study included a subset of vaccinees who were enrolled for the cellular component of MAL067, an immunology ancillary study to the RTS,S/AS01E phase 3 trial (Malaria-055, ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00866619), which has been previously described8,16. Study participants included children aged 5–17 months (age at first dose) and infants aged 6–12 weeks, who were vaccinated with three primary doses at one-month intervals of either RTS,S or a comparator vaccine, which was meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (Menjugate™, Novartis) for infants and rabies vaccine (VeroRab™, Sanofi Pasteur) for children. At M20, a booster dose was given to the three trial groups as follows: (i) three primary doses of RTS,S followed by an RTS,S booster (R3R); (ii) three primary doses of RTS,S followed by a comparator dose (R3C), and (iii) three primary comparator vaccine doses followed by a comparator vaccine boost (C3C) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Both age cohorts received the Menjugate™ vaccine as comparator at M20. Malaria cases were participants presenting clinical malaria (fever ≥ 37.5 °C and parasite-positive blood smear) over an 11-month follow-up period between M21 and M32, and controls were participants without malaria. Prior exposure to malaria was assessed for the one year leading up to the booster dose at M20. Demographic factors such as hemoglobin concentrations and WAZ were measured at M20. Manhiça Health Research Center, Fundação Manhiça, in Mozambique, and Ifakara Health Institute and Bagamoyo Research and Training Centre, in Tanzania, participated in this study, and both sites had low-medium malaria transmission intensity8,34,35. Infants and children were recruited in Manhiça, whereas Bagamoyo only included children.

PBMC collection and stimulation

PMBCs were collected at M21 and M32, isolated and stimulated onsite as previously described16. Briefly, blood was collected from infants and children using BD Vacutainer® heparin tubes and BD Vacutainer® CPT™ sodium citrate tubes, respectively. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation, quantified with a Countess automated cell counter (Life Technologies), and then resuspended in culture medium (RPMI-1640, Gibco, SKU# 42401-042) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Patricell, L82263), and penicillin-streptomycin-L-glutamine (Gibco, SKU#10378-016). Cells were plated in a 96-well, U-bottom culture plates (Costar, Cultek Cat No. CLS3799-50EA) at a concentration of 4×105 cells per well in duplicate and allowed to rest for 12 h in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. Stimulations were performed in duplicate with peptide pools from CSP (31 peptides) and HBsAg (53 peptides) consisting of 15-mers overlapping by 11 amino acids, with individual peptides tested at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml (Biosyntan, Germany)14. PHA-P (Sigma-Aldrich, L1668) was the positive control, and DMSO, the peptide solvent (Sigma-Aldrich, D2650), was the negative background control. Following stimulation for 12 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, cells were centrifuged at 250 x g for 5 min at room temperature, then 180 μL of supernatant were collected from each replicate and stored at −80 °C in 96-well V-bottomed plates (Kisker, AttendBio, G096-VB) sealed with adhesive foil (Kisker, AttendBio G071-P) until analyzed. All available samples were analyzed for this study.

Multiplex bead array assay

The 30-Plex Human Cytokine Magnetic Panel for Luminex® (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to quantify the following cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors present in collected culture supernatants: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), GM-CSF, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-2R, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p40/p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, TNF, Eotaxin, IFN-γ induced protein (IP-10), MCP-1, monokine induced by IFN-γ (MIG), MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and vascular epidermal growth factor (VEGF). A modified version of the manufacturer’s protocol was followed in which half of the volume of all kit reagents was used except for the assay wash buffer16, and 25 μL of supernatant from each sample were tested. Plates were read on a Luminex® 100/200. Randomized sample distribution was used according to the site, age cohort, vaccination, and case/control to ensure balanced testing across assay plates. Each assay plate included a standard with known concentrations of each analyte (provided by the kit) that was used to prepare a curve with serial dilutions, as well as two blank controls and three reference sample positive controls prepared with the standard and with low, medium, and high analyte concentrations tested in duplicate for quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC).

QA/QC was performed using drLumi, an R package developed by our group36, which fitted the standard curves based on four- or five–parameter log-logistic models. Limits of quantification (LOQ) were based on a cutoff value (30%) of the coefficient of variation (CV) for the standard curve of each analyte. The analytes IL–6, IL–8, Eotaxin, HGF, IFN–α, and IL–7 had more than 30% of measurements below or above the LOQ, and therefore were excluded from the study. For all other markers, concentrations that could not be estimated for being outside the quantification range were imputed according to the following boundaries: i) for median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values under the lower LOQ or flagged as not quantified, the lower LOQ and half of the LOQ were used as boundaries for a random imputation; ii) for MFI over the upper LOQ or flagged as not quantified, the upper LOQ and double of the upper LOQ were used as boundaries for a random imputation.

Antibody data

Antibody data against vaccine antigens analyzed for correlations with cytokine responses were obtained in previous studies and were available only for participants from Manhiça. Specifically, IgG levels (EU/mL) against NANP measured by ELISA were obtained from the MAL055 clinical trial (CEVAC ELISA5,37). IgG and IgG subclass levels (quantified as MFI) against P. falciparum CSP antigens: CSP CSP FL, NANP, and the Cterm were measured by Luminex at ISGlobal9. Due to low participant overlap between cytokine and antibody studies (N = 39 for ELISA data and 31 for Luminex data) and since we observed minor differences for cellular immunogenicity markers elicited by the booster dose, R3R (RTS,S-boosted) and R3C (RTS,S-unboosted) were analyzed together for correlations with antibody levels.

Statistical analyses

Similarly to our previous study16, the main analysis was based on ratios between analyte concentrations after stimulations with the corresponding antigen of interest (CSP or HBsAg) and background (DMSO) to assess antigen-specific responses. Analysis of antigen-specific responses through antigen/background ratios proved more reliable and had lower variability across plates than background subtractions. Cytokine ratio analyses were complemented with crude concentration analyses, and in both cases, data was log10 transformed. As some substantial outliers resulted in skewing the data distribution, data from all markers were truncated based on the 99.75 percentile. Fold differences and their 95% CI in geometric means between groups were estimated by regressing log-transformed concentrations on the group variable and exponentiating back the regression coefficients. We also used Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to compare the distribution of log-transformed concentration ratios between groups. Effect modifiers of immunogenicity were evaluated through interactions with the vaccination group in regression models. Only participants from Manhiça were analyzed for the effect modification of age, and only children were analyzed for the effect modification of site. The association of cytokine responses with the risk of clinical malaria was assessed through Cox regression. Cytokine concentrations were scaled to ensure that the estimated HR could be interpreted as comparing hazards of malaria when log-transformed cytokine levels were increased by one standard deviation. CI and significance for HR were based on Wald tests on the corresponding Cox regression coefficient. We conducted several different HR estimations and tests for each cytokine of interest:

-

1.

HRs within each vaccination group (stratified analysis).

-

2.

A test on the effect modification of the vaccination group. This was assessed as an interaction in models, including all three vaccination groups. Significance was tested with a log-likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without the interaction terms.

-

3.

HRs within all vaccination groups together, that is, the main effect of cytokine levels independent of any effect modification by the vaccination group. This was obtained from the same regression models as in 2), using an effect-coded regressor design matrix, which made the regression coefficient for the cytokine levels and its associated HR interpretable in the presence of interaction terms.

Tests were two-tailed, and p-values were considered statistically significant to a 0.05 α-level. Asterisks were used to indicate significant results after adjustment to keep a false discovery rate (FDR) < 5% by applying the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Spearman correlation was used to measure correlation coefficients and statistical significance between cytokines and antibody responses. Due to the exploratory nature of this antibody-cytokine correlation analysis, p-values were not adjusted for multiple testing. All analyses were performed using R, and Cox regression analyses were fitted with the survival package (version 3.2–7)38.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

The code used for this study will be made available to qualified researchers upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization. WHO recommends groundbreaking malaria vaccine for children at risk. https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2021-who-recommends-groundbreaking-malaria-vaccine-for-children-at-risk.

Garçon, N. & Van Mechelen, M. Recent clinical experience with vaccines using MPL- and QS-21-containing Adjuvant Systems. Expert Rev. Vaccines 10, 471–486 (2011).

Laurens, M. B.RTS,S/AS01 vaccine (MosquirixTM): an overview. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2019;5515, https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1669415.

McCall, M. B. B., Kremsner, P. G. & Mordmüller, B. Correlating efficacy and immunogenicity in malaria vaccine trials. Semin Immunol. 39, 52–64 (2018).

White, M. T. et al. Immunogenicity of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine and implications for duration of vaccine efficacy: secondary analysis of data from a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 15, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00239-X (2015).

Ubillos, I. et al. Baseline exposure, antibody subclass, and hepatitis B response differentially affect malaria protective immunity following RTS,S/AS01E vaccination in African children. BMC Med 16, 197 (2018).

Dobaño, C. et al. Concentration and avidity of antibodies to different circumsporozoite epitopes correlate with RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine efficacy. Nat Commun.10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10195-z (2019).

RTS SCTP. Efficacy and safety of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: final results of a phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial. Lancet.386, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60721-8(2015).

Sanchez, L. et al. Antibody responses to the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine and Plasmodium falciparum antigens after a booster dose within the phase 3 trial in Mozambique. npj Vaccines 5, 1–16 (2020).

Sun, P. et al. Protective Immunity Induced with Malaria Vaccine, RTS,S, Is Linked to Plasmodium falciparum Circumsporozoite Protein-Specific CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells Producing IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 171, 6961–6967 (2003).

Kester, K. E. et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase 2a trial of falciparum malaria vaccines RTS,S/AS01B and RTS,S/AS02A in malaria-naive adults: Safety, efficacy, and immunologic associates of protection. J. Infect. Dis. 200, 337–346 (2009).

Lumsden, J. M. et al. Protective immunity induced with the RTS,S/AS vaccine is associated with IL-2 and TNF-α producing effector and central memory CD4 + T cells. PLoS One 2011;6, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020775. (2011).

Barbosa, A. et al. Plasmodium falciparum-specific cellular immune responses after immunization with the RTS,S/AS02D candidate malaria vaccine in infants living in an area of high endemicity in Mozambique. Infect. Immun. 77, 4502–4509 (2009).

Olotu A. et al. Circumsporozoite-specific T cell responses in children vaccinated with RTS,S/AS01 E and protection against P falciparum clinical malaria. PLoS One. 6, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025786 (2011).

Ndungu, F. M. et al. A Statistical Interaction between Circumsporozoite Protein-Specific T Cell and Antibody Responses and Risk of Clinical Malaria Episodes following Vaccination with RTS,S/AS01E. PLoS One.7, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052870 (2012).

Moncunill, G. et al. Distinct helper t cell type 1 and 2 responses associated with malaria protection and risk in rts,s/as01e vaccinees. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65, 746–755 (2017).

Moris, P., Jongert E., van der Most R. G. Characterization of T-cell immune responses in clinical trials of the candidate RTS,S malaria vaccine. Hum Vaccines Immunother.14, https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2017.1381809 (2018).

Agnandji, S. T. et al. Induction of Plasmodium falciparum-specific CD4+ T cells and memory B cells in gabonese children vaccinated with RTS,S/AS01E and RTS,S/AS02D. PLoS One.6, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018559 (2011).

Moncunill, G. et al. RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine induces memory and polyfunctional T cell responses in a pediatric African phase iii trial. Front Immunol.8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01008. (2017).

Pallikkuth, S. et al. A delayed fractionated dose RTS,S AS01 vaccine regimen mediates protection via improved T follicular helper and B cell responses. Elife 9, 1–25 (2020).

Hill D. L. et al. Immune system development varies according to age, location, and anemia in African children. Sci. Transl. Med.12, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw9522 (2020).

Ansong, D. et al. T cell responses to the RTS,S/AS01e and RTS,S/AS02D malaria candidate vaccines administered according to different schedules to Ghanaian Children. PLoS One 6, 1–9 (2011).

Horowitz, A. et al. Antigen-Specific IL-2 Secretion Correlates with NK Cell Responses after Immunization of Tanzanian Children with the RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine. J. Immunol. 188, 5054–5062 (2012).

Darrah, P. A. et al. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat. Med 13, 843–850 (2007).

Seder, R. A., Darrah, P. A. & Roederer, M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: Implications for vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 247–258 (2008).

Le Gallou, S. et al. IL-2 Requirement for Human Plasma Cell Generation: Coupling Differentiation and Proliferation by Enhancing MAPK–ERK Signaling. J. Immunol. 189, 161–173 (2012).

Litjens, N. H. R. et al. IL-2 producing memory CD4+ T lymphocytes are closely associated with the generation of IgG-secreting plasma cells. J. Immunol. 181, 3665–3673 (2008).

Hugosson, E. et al. Higher IL-10 levels are associated with less effective clearance of Plasmodium falciparum parasites. Parasite Immunol. 26, 111–117 (2004).

Zhang, G. et al. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) polymorphisms are associated with IL-10: Production and clinical malaria in young children. Infect. Immun. 80, 2316–2322 (2012).

Swanson, B. J. et al. RANTES production by memory phenotype T cells is controlled by a posttranscriptional, TCR-dependent process. Immunity 17, 605–615 (2002).

Conti, P. et al. Expression and secretion of RANTES by human peripheral blood CD4+ cells are dependent on the presence of monocytes. Ann. Clin. Lab Sci. 31, 75–84 (2001).

Frauenschuh, A. et al. Differential polarization of immune responses by co-administration of antigens with chemokines. Vaccine 23, 546–554 (2004).

Obeng-Adjei, N. et al. Circulating Th1-Cell-type Tfh Cells that Exhibit Impaired B Cell Help Are Preferentially Activated during Acute Malaria in Children. Cell Rep. 13, 425–439 (2015).

The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership. A Phase 3 Trial of RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine in African Infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2284–2295 (2012).

The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership. First results of phase 3 trial of RTS,S/ AS01 malaria vaccine in African children. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1863–1875 (2011).

Sanz, H. et al. drLumi: An open-source package to manage data, calibrate, and conduct quality control of multiplex bead-based immunoassays data analysis. PLoS One 12, 1–18 (2017).

Clement, F. et al. Validation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the quantification of human IgG directed against the repeat region of the circumsporozoite protein of the parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Malar. J. 11, 1–15 (2012).

Therneau, Terry M. Grambsch, P. M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. 1–350 (New York, NY, 2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants of the study and their families. We are grateful to the MAL055 clinical team; the field and laboratory personnel from CISM, ISGlobal, and IHI-BRTC, in particular, Núria Díez-Padrisa and Nana Williams for their support. We thank Lina Sanchez and Marta Vidal for contributing the antibody data. We are also grateful to the members of the MAL067 Vaccine Immunology Consortium investigators. We thank GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA for their support, in 2008–2009, for developing the study plan and for transferring custodianship of the MAL067 samples to ISGlobal. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA was provided the opportunity to review a preliminary version of this manuscript for factual accuracy, but the authors are solely responsible for final content and interpretation. We also thank PATH’s Center for Vaccine Innovation and Access (via a Core 2 grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grant No. OPP48782) for their support in the conduct of the MAL067 Study. We thank Neville Kisalu (PATH) for reviewing this manuscript prior to submission. GM is supported by RYC 2020–029886‑I/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, co‑fundedby European Social Fund (ESF). The study was supported by funds from NIH-NIAID (USA, R01AI095789, U01AI165745), and the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, PI11/00423 and PI17/02044) cofounded by FEDER funds/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). We acknowledge support from the grant CEX2023-0001290-S funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and support from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA Program. This research is part of the ISGlobal’s Program on the Molecular Mechanisms of Malaria which is partially supported by the Fundación Ramón Areces. CJ was supported by an AGAUR-FI scholarship (2019 FI_B 00986) granted by the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Empresa i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya and co-funded with Social European Fund. RM was supported by a scholarship from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PFIS-FI18/00295). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. D.M., C.Do, and G.M. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. D.M. and R.M. analyzed the study data and interpreted results with C.Do and G.M.; G.M., C.Do, and C.Da conceived and designed the cellular immunology experiments. M.M., C.Da, C.Do, C.J., J.J.C., and G.M. processed the samples and performed the stimulations. C.Do and G.M. led the development of the experiments. C.J., R.M., A.N., A.C., and R.A. performed the Luminex assays. R.A. managed Luminex plate design and coordinated Luminex assays. R.M., C.J., D.M., R.A., C.Do, and G.M. developed the analytical plans. M.V., R.A. and G.M. performed Luminex data QA/QC and M.V. performed data preprocessing. C.Da and C.Do were site PIs for the immunology study. P.A. was the CISM PI for the MAL055 study. All authors agree with the manuscript results and conclusions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.J.C. is employed by Antigen Discovery Inc., Irvine, CA, United States, but declares no financial or non-financial competing interests. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be seen as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitchell, R.A., Macià, D., Jairoce, C. et al. Effect of RTS,S/AS01E vaccine booster dose on cellular immune responses in African infants and children. npj Vaccines 9, 200 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00977-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00977-y