Abstract

Enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) is a significant public health concern, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, where it commonly causes hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks. There are no clinically available antivirals, and use of inactivated vaccine is restricted to China. This review explores patterns of humoral immune response to EV-A71, highlights critical epitopes, and discusses vaccine development. Critically, we examine the challenges facing EV vaccination strategies, as well as future directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enteroviruses (EVs), members of the Picornaviridae family, are highly contagious and prevalent viruses with the potential to cause localized outbreaks and burden global health infrastructure1. Apart from respiratory EVs2, EVs are predominantly transmitted via the fecal-oral route, causing a wide array of diseases ranging from asymptomatic infection to fever, hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD), herpangina, respiratory or gastrointestinal illness, conjunctivitis, encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, acute flaccid myelitis, or myocarditis3,4.

To date, over 100 human-infecting non-respiratory EVs have been identified around the world1. This rather large number and ubiquitous global distribution highlights the profound diversity of this group of viruses. EVs are classified into 15 species according to the sequence of their capsid protein, VP1. Here, we focus on EV-A71, a member of the Enterovirus alphacoxsackie A species (formerly named Enterovirus A species)3. EV-A71 can be further classified into four genogroups (A to D) and 13 subgenogroups (A, B1-5, C1-6, and D)5,6. Their geographical distribution varies, with subgenogroups B3-5 and C2-5 observed in the Asia Pacific, while C1, C2, and C4 are dominant in Europe7. The vast genetic diversity of EV-A71 circulating strains further poses additional challenges to developing cross-protective vaccines. There is, thus, a need to clarify the interplay between immunity and co-circulating EV-A71 strains. Here, we aim to provide an overview of vaccine development and current knowledge of humoral immunity to EV-A71, including antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), as well as the implications and challenges for vaccine development. We will commence our discussion with a comprehensive overview of EV-A7, focusing on the biology, epidemiological significance, and diagnostics, before diving into humoral immunity, vaccination, and therapeutic monoclonal antibodies.

EV-A71 biology

EV-A71 is a small (~30 nm) non-enveloped virus8 with a positive sense single-stranded RNA genome that codes for a single open reading frame (ORF) flanked by 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs)9 (Fig. 1A). The ORF is divided into three central regions: P1, P2, and P3. The P1 encodes the structural capsid proteins (VP1–VP4)10. P2 and P3 encode non-structural proteins (2 A, 2B, 2 C, 3 A, 3B, 3 C, and 3D) critical for viral replication, structural reorganization of the host cell, and immune evasion.

A Depiction of the EV-A71 genome, polyprotein, precursor proteins, and processed proteins. Triangles indicate the protease responsible for cleavage. B A three-dimensional schematic of the EV-A71 virion was obtained from the protein database entry 6UH1182. VP1, VP2, and VP3 are depicted in green, purple, and orange, respectively. Fivefold, threefold, and twofold axes of symmetry are indicated in dashed black lines. C Based on the 6UH1 structure182, a three-dimensional schematic of the capsid proteins VP1-4 was generated using ChimeraX. Key structural features relevant to host humoral response are highlighted with bold lines for epitopes in the visual plane and dashed lines for antigenic sites that are out of view. VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 are colored in green, purple, orange, and black, respectively. D Schematic of the EV-A71 life cycle. Key steps in the life cycle are indicated in bold. Briefly, EV-A71 attaches to the receptor, is endocytosed, the virus uncoats and the viral genomic RNA is released into the cytosol, where it can be translated and processed into various viral proteins or used as a template for replication. Virus particles are assembled, matured, and released via lytic or non-lytic pathways. Image generated using Biorender.

Specifically, the EV-A71 virion comprises 60 copies of VP1-4 that assume icosahedral symmetry8 with a pseudo-T = 3 symmetry8(Fig. 1B). VP1 is the immunodominant epitope10. VP1, VP2, and VP3 project outward on the viral surface, while VP4 lies beneath and interacts with the genomic RNA. The capsid threefold, twofold, and fivefold axes of symmetry define distinct structural features. The threefold axis is where the VP2 and VP3 proteins meet, creating the canyon region, a deep depression in the virion surface11 (Fig. 1C). Variable loops serve as antigenic sites and facilitate functions such as receptor binding12. Notably, the VP1 GH loop and the VP2 EF loop interact with host receptor scavenger receptor B–member 2 (SCARB2)13,14. Additionally, the BC loop of VP1, situated near the fivefold axis, is an antibody target15,16. The VP3 knob region is the most prominent protrusion on the surface of the virion, while the VP2 puff region is the largest perturbation of the VP2 protein and forms part of the canyon ridge12. Both the VP2 puff and the VP3 knob are immune targets15,17. Together, these structural features define the virion architecture and mediate critical functions such as receptor binding, immune evasion, and host recognition.

EVs typically infect the host through mucosal tissues and can disseminate to different organ compartments in the body18. EV-A71 replicates predominantly in the intestinal mucosa, where it enters the cell after binding to SCARB2, the primary uncoating receptor13. Other secondary receptors such as P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1), sialylated glycans, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and annexin II (Anx2) have been reported to facilitate infection19. Several internalization mechanisms have been described for EV-A7120, but the predominant pathway is through SCARB2-mediated pH-dependent endocytosis (Fig. 1D). Upon receptor binding, the virus undergoes clathrin-mediated endocytosis, where the increasingly acidic pH environment of the lysosome triggers the release of the viral RNA genome into the cytoplasm21. Subsequently, a type 1 internal ribosomal entry site recruits the host ribosomes to initiate cap-independent translation of the positive strand RNA22,23. The translated polyprotein then undergoes post-translational proteolytic processing to generate precursor and mature proteins (Fig. 1A, D). Replication begins once new polymerases are available. The viral protein VPg (3B), covalently attached to the viral genomic RNA, acts as a primer to initiate replication18. An intermediate negative-sense strand is synthesized and serves as a template to produce a plethora of nascent positive-sense viral RNA strands, which can either be translated into viral proteins or packaged in new virions. Progeny virus can either be released from the cells during lysis24 or by alternative non-lytic pathways25.

EV-A71 seroepidemiology and prevalence

With the biological characteristics of EV-A71 now outlined, the following section focuses on its seroepidemiology and prevalence, offering a broader perspective on its distribution and public health significance. EV-A71 mainly causes outbreaks in parts of Cambodia26, China27, Japan28, Malaysia29, Singapore30, Taiwan31, Thailand32, and Vietnam33. The absence of dedicated surveillance systems is a key challenge in determining the true impact of EV-A71 infections. Given that infections may be asymptomatic, serological tools are particularly beneficial in estimating EV-A71 prevalence. EV-A71 seroprevalence ranges from 88.8 to 4.31% based on a meta-analysis of seroprevalence studies from areas of high endemicity, such as South East Asia, to less endemic regions, including countries in continental Europe and South America34.

Although EV-A71 seroprevalence varies by region, age-dependent trends in serology are shared globally34. Generally, maternal anti-EV antibodies are detected at birth but decrease within the first six months27. Anti-EV antibodies increase again from between 6 months to two years onwards28,35 (Fig. 2). For example, in a Vietnamese study, antibodies against EV-A71 were present in 55% of cord blood, four percent of infants at nine months, and 84% of children aged 5–15 years old33. Disease severity peaks between 6 months to 2 years36, coinciding with the drop in anti-EV antibodies. HFMD occurs most frequently in children under 4 years of age, and infections become increasingly rare throughout adulthood37.

A sharp decrease in serum antibodies within the first six months of life coincides with an increase in EV infections in the first two years of life. These infections result in seroconversion, and as a result, the seroprevalence gradually increases as more people are infected and develop immunity. Illustration made with Biorender.

Severe disease and death have been reported in immunocompromised patients38,39. Particularly, individuals with B-cell deficiencies, as a result of host genetics38,40 or immunosuppressive therapies39,41, are at increased risk for prolonged infection and neuronal complications. As infections can be prolonged in these patients, they also serve as a potential reservoir for the emergence of novel EV-A71 genetic variants42.

EV-A71 outbreaks occur approximately every 3 years43, a pattern supported by seroprevalence peaks observed with similar periodicity26. The periodic decrease in seroprevalence may result from several factors, including waning immunity over time and introducing susceptible individuals into the population through birth or immigration. Moreover, HFMD transmission is influenced by seasonality, with peak occurrences varying by region. HFMD typically occurs between March and May in Singapore37, in June in Southern China, and in May, September, and October in Northern China44. Specifically, sudden changes in temperature, precipitation, and humidity have been highlighted as factors influencing transmission risk45. The variability of these factors, compounded by increased globalization, highlights the need for enhanced and coordinated global surveillance efforts.

EV-A71 surveillance and diagnostics

Globally, EV-A71 surveillance data varies between regions, with some areas having limited surveillance. Improving and standardizing EV-A71 surveillance could help forecast which subgenogroups are becoming more prevalent and will require vaccination in the future.

Regions in the Asia Pacific region, including China46, Singapore47, and Taiwan35, actively monitor EV transmission. In 2017, the European Non-Polio Enterovirus Network was established and issued recommendations regarding EV diagnosis and monitoring48, which has been ongoing across twenty European countries. From 2015 to 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) Western Pacific Regional Office released annual Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease Situation Updates and bi-weekly surveillance summaries. However, data from other regions is lacking. In addition, asymptomatic infections make EV surveillance particularly challenging, and several EV infections are often undiagnosed.

The WHO’s Guide to Clinical Management and Public Health Response to Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease recommends testing for HFMD cases from vesicles, as they represent current systemic infection. Harvala et al. recommend testing respiratory, stool, and blood samples in addition to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), heart biopsy, and eye swabs based on clinical manifestations that include neurological, cardiac, or ophthalmological complications, respectively48. Virus isolation and EV identification through molecular techniques such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or neutralization assays are advised by the WHO49. Nested PCR targeting the 5’UTR, VP1, and VP4/VP2 regions can identify EV, while virus-specific RT-PCR focusing on the VP1 gene can provide precise virus characterization49. However, testing for each EV genogroup via RT-PCR is expensive and labor-intensive. Diagnostics based on serology, specifically IgM, have been explored50. Yet, these tests lack genogroup specificity and do not necessarily reflect a current infection. In fact, serology can be used to differentiate between primary and secondary infections. A rapid increase of IgM and a delayed IgG response following symptom onset is indicative of a primary EV-A71 infection, whereas a robust IgG response at symptom onset signifies previous exposure51,52. EV can occasionally be detected in CSF. In cases with suspected central nervous system involvement, EV could only be detected in ~2.5% of cases53. This is likely related to a lag between the presence of the virus in the brain and the onset of host response-related symptoms. Site-of-care rapid antigen tests that can discriminate between EVs have yet to be developed and made commercially available. Such tests would be incredibly valuable for surveillance and implementation of appropriate strategies to support symptomatic management. In addition, a comprehensive understanding of the clinical manifestations of EV-A71 infection is crucial for improving case recognition and guiding appropriate clinical management.

EV-A71 infection and humoral response

EV-A71 can manifest as HFMD, characterized by self-limiting febrile illness with oral ulcers and a papulovesicular rash on the hands and/or feet54. Alternatively, herpangina can be observed, in which ulcers are present in the back of the oral cavity. Children under 2 years old are more likely to present with atypical rashes. Complications include aseptic meningitis, encephalomyelitis, encephalitis, and acute flaccid paralysis55. Other EVs from the enterovirus alphacoxsackie species can also cause HFMD and herpangina, but EV-A71 has been more frequently associated with neurological complications25.

The incubation period of EV-A71 ranges from three to six days from exposure to symptom onset (Fig. 3)56. Symptom onset coincides with detection of viral RNA and induction of immune response57,58. Viremia gradually decreases following symptom onset (Day 0) and is cleared by day 758 (Fig. 3).

The incubation period is 4–6 days from virus exposure to symptom onset (Day 0). The percentage of patients with detectable viral RNA from serum (pink) decreases from symptom onset (day 0) with viremia (red) peaking at symptomatic day three and four58. The dashed red line is used to express a rise in serum EV-A71. However, as this period is before symptom onset, limited data is available to concretely describe viremia levels. The geometric mean titer of serum nAbs (blue) ranged from ~100 to at day 1 post symptom onset to ~1000 at day five60 or six59, depending on the study. SIgA (black) peaks between 6–10 days after symptom onset and decreases thereafter based51. Figure made with Biorender.

On the other hand, anti-EV-A71 neutralizing antibodies (nAb) begin to increase from illness onset54. The level of anti-EV-A71 nAb in children aged two months to 12 years from Zhengzhou and Henan, China, peaked around day 13 and remained elevated for at least 26 months following infection59,60. Notably, almost all patients (80-90%) were seropositive from illness onset60. Specifically, Xu et al. showed that IgM levels increase in the first four days of symptomatic infection and remain elevated for ~40 days61. On the other hand, anti-EV-A71 IgG has been found up to 60 days after the symptomatic presentation started. Patients with severe infection produce significantly higher nAb titers than those who experience mild infection60.

IgA antibodies are found in two forms. Secretory IgA (SIgA) is secreted predominantly in dimeric form from the mucus membrane lining the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. IgA can additionally be observed in the circulatory system, where IgA tends to be monomeric62. SIgA is important in defense against EV, as they are secreted at the primary sites of infection and replication. Efforts have been made to establish SIgA-based diagnostic tests for EV-A71 from patient saliva51. However, anti-EV-A71 SIgA from saliva does not persist as long as IgM, peaking between six and ten days after symptom onset and dropping below the detection level after 21 days51. Anti-EV-A71 nAbs confer protection in humans15,63,64 and in vivo models, including non-human primates and mouse models65,66. The respective contribution of IgA and SIgA to the prevention of EV-A71 infection remains to be better defined.

SIgA found in the mucosa can interact with specific antigens through the canonical fragment antigen binding (Fab) region or non-specific antigens via non-canonical binding mediated by glycans on the j-chain of dimeric IgA67. While IgA non-specific non-canonical binding of antigen has been demonstrated for gram-positive bacteria68, less is known about IgA non-specific binding of viruses, and its involvement in anti-EV-A71 immunity remains to be investigated. Nevertheless, established antibody-mediated mechanisms of viral neutralization provide critical insights into the broader landscape of humoral immunity against enteroviruses.

Mechanisms of neutralization

Antibody responses to EV infections, specifically mechanisms of neutralization, have been extensively reviewed recently69. Antibodies can inhibit viral infection by several distinct mechanisms, including a) preventing virus binding to cellular receptors, b) impeding essential conformational changes required for viral uncoating and RNA release, c) inducing premature virus uncoating and RNA release, d) encouraging virus aggregation, and d) antibody-mediated proteolysis. Alternative mechanisms of viral clearance mediated by antibodies include antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), whereby antigens marked by antibodies are targeted for degradation by phagocytes and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) in which immune cells, including natural killer cells, macrophages or neutrophils, kill infected cells that have been coated with antibody as a result of antigen exposure, ingestion and display of antigen peptides at the cell surface.

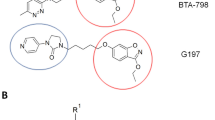

Neutralization of EV-A71 mediated by blocking receptor binding has been demonstrated for mouse-derived anti-EV-A71 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) A9, D5, D6, and C4, all of which recognize the GH loop on the VP1 protein that partially overlaps with the SCARB2 binding site14,15,70 (Fig. 1C). The mAb D5, elicited in response to a conformational epitope, additionally interacts with the virion at the twofold icosahedral symmetry axes and exhibits a stabilizing effect, thus thwarting the conformational changes required for uncoating and RNA release70. In contrast, mAb E18 binds to mature virions and induces premature uncoating, resulting in the release of viral RNA71.

The additional neutralization mechanisms previously mentioned have not yet been observed to prevent EV-A71 infection. However, these have been reported for other EVs. Virus aggregation neutralizes poliovirus, a member of the Enterovirus coxsackiepol species (previously known as Enterovirus C species). Specifically, mAb 35-1f4 reduced the number of infectious poliovirus particles in vitro by forming large immune complex aggregates72. Furthermore, antibody-mediated proteolysis, where the Fc portion of endocytosed opsonized viruses triggers TRIM-21 to recruit host proteases for viral degradation, has been observed in Enterovirus alpharhino species (formerly referred to as Rhinovirus A species)73. ADCP and ADCC have been identified as important mechanisms of viral infection with related Enterovirus alpharhino and Enterovirus alphacoxsackie species, respectively74,75. Together, these findings underscore the diversity of antibody-mediated neutralization strategies across enteroviruses and highlight the need for a deeper understanding of epitope-specific response, especially those that elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies against EV-A71 and related viruses.

Epitopes

Given the diversity within the Enterovirus alphacoxsackie species, identifying epitopes with the capacity to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies against multiple genotypes is of paramount importance and has implications for vaccine efficacy, the development of diagnostics, and the design of therapeutics and monoclonal antibodies. VP1 is the primary immunodominant protein target (Fig. 4A), although antibodies have been isolated from human sera against other structural and non-structural EV proteins, including VP2, VP3, 2 C, 3 C, and 3D76,77,78.

A Schematic representation of linear epitope sites on the structural proteins targeted by anti-EV cross-reactive IgM and IgG based on Supplementary Table 1. The epitope names refer to the names assigned in the paper describing them. B Epitope sequences. Note that similar epitopes have been described in multiple papers under different names. For example, the amino-acid sequences of SP70183 and VP1-8119 are YPTFGEHKQEKDLEYC and PTFGEHKQEKDLE, respectively. Moreover, several epitopes overlap. For example, E2 (PALTAVET) can be found in the E1 epitope (PALTAVETGATNPL). If the epitope is found within a linear sequence that forms a loop of known importance for viral interactions, the name of the loop is included in parentheses. C, D A three-dimensional image of VP1-4 was generated in ChimeraX using the 6UH1 structure from the protein database182. Linear epitopes targeted by IgM (C) and IgG (D) are highlighted in pink (VP1), blue (VP4), and yellow (VP2). Image generated using Biorender.

An exhaustive list of published epitopes recognized by human IgM and IgA antibodies is presented in Supplementary table 1, while Fig. 4 highlights representative linear epitopes targeted by human IgM (Fig. 4B, C) or IgG antibodies (Fig. 4B, D). Human IgM and IgG predominately target epitopes located in VP1, of which several linear epitopes have been well characterized76,77,78. As mentioned above, the VP1 GH loop is an immunodominant antigenic site8. Likewise, the VP2 EF loop, the canyon region and the region between the twofold and threefold axes are commonly targeted by anti-EV antibodies8,70,78,79. Of note, epitopes targeted by IgA have not been well characterized in EV-A71 infection.

Remarkably, there is limited overlap between linear epitopes targeted by human, mouse, and rabbit sera80. This highlights that the underlying B-cell repertoire in different species may lead to distinct polyclonal antibody responses80 and suggests that neutralizing epitopes identified in model organisms should be cautiously approached as they may not translate between hosts.

Conformational epitopes have additionally been described for EV-A71, although to a lesser extent than linear ones11,15. Most epitope mapping work has been performed by mutagenesis, and high-resolution structural data are available for seven antibodies in complex with EV-A7181. Notably, mAb A9 interacts with the puff region, BC loop, and α2 on VP3 as well as the C-terminus of VP1, while mAb D6 targets the GH loop of VP2, the puff and BC loop of VP3, and the C-terminus of VP1 (Fig. 1C). A9 and D6 both occlude SCARB2 binding15 (Supplementary table 1). Meanwhile, 38-1-10 A and 38-3-11 A isolated from patient sera interact near the threefold symmetry axis of the icosahedral virion and effectively protect mice from lethal EV-A71 challenge11. On the other hand, neutralizing mAb 10D3, derived from a murine model, targets a few residues in the VP3 knob region and is effective in neutralizing all EV-A71 genogroups in vitro17 (Fig. 1C). Likewise, conformational epitope M1-16, derived from human sera, maps to two amino acids on the VP1 BC loop82 (Fig. 1C). Recently, in silico bioinformatic approaches have been implemented to predict conformational epitopes of EV-A71 and CVA1683. However, follow-up in vitro efficacy assays are required to confirm the accuracy of these methods.

Epitopes that lead to serotype-specific and broadly reactive immunity have been identified (Supplementary Table 1)77,78. Several conserved epitopes exist, yet cross-protection from an initial natural infection is rare, and multiple subsequent HFMD infections are required to enrich cross-neutralizing antibodies. This is consistent with data by Saarinen et al., which showed that children tend to have fewer cross-reactive antibodies than adults, who generally have a more robust antibody response84. Consequently, this raises questions regarding the role of the immune imprinting in enterovirus infections, where the immune system relies on the memory of previous exposure to a similar virus to mount a secondary immune response against the novel strain that may result in an immune response that is insufficient to protect the host against disease85. Immune imprinting is a phenomenon frequently described in viruses with high mutation rates, such as influenza. Limited evidence suggests that immune imprinting may be involved in secondary infection with related Enterovirus echovirus 3086, yet to our knowledge, immune imprinting has not been observed in EV-A71 infections. However, a similar and potentially harmful antibody-mediated mechanism, known as ADE87, has been described in enteroviruses and will be further discussed in the next section.

Antibody-dependent enhancement

While neutralizing antibodies offer protection against subsequent infection, non-neutralizing, subneutralizing, or waning antibodies can lead to enhanced infection rather than protection. This paradoxical phenomenon, referred to as antibody-dependent enhancement, was first described in 196488 and has been widely documented in flaviviruses89. ADE has been suggested to play a role in exacerbating EV infections87.

Mechanistically, ADE can occur in a fragment crystallizable region receptor (FcR) dependent or an FcR-independent manner (Fig. 5)90. FcR-dependent ADE is the most common and widely studied ADE pathway in viral infection (Fig. 5A). There are two FcR-dependent ADE pathways, the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. In the extrinsic FcR-dependent ADE pathway, non-neutralizing antibodies mediate viral entry via interaction with FcRs on immune cells91, enhancing the infection by increasing the number of infected cells92. In contrast, the intrinsic ADE pathway occurs when the FcR internalized antibody-virus complex modulates the antiviral response, enabling increased viral replication, sustained infection, and higher progeny virus production by the infected cell92. Of note, both mechanisms could theoretically co-occur93.

A FcR-dependent extrinsic and intrinsic ADE pathways91,184,185. The FcR-dependent ADE extrinsic pathway entails sub-neutralizing antibodies binding to the virus, facilitating virus entry into the cell via the FcR. The intrinsic FcR-dependent ADE pathway is characterized by a downregulation of the host antiviral and pro-inflammatory responses driven by endocytosis of the antigen-antibody complex. B Complement-dependent ADE occurs due to C1q binding to the opsonized virus and facilitating endocytosis of the virus via the C1qR. C FcR-independent antibody facilitated viral entry, whereby a mAb binds the primary receptor and induces a conformational change that exposes the binding sites of the co-receptor, promoting virus entry. The figure was generated using biorender.

Alternatively, enhanced virus entry can occur in an FcR-independent manner. Complement-dependent ADE, whereby aggregation of antigen–antibody complex facilitates C1q binding to the antibody Fc region and enables virus entry via C1q receptors (C1qR) on diverse cell types, including fibroblasts and endothelial cells (Fig. 5B)94. Additionally, a novel mechanism of antibody-assisted virus entry has been recently reported for viruses with co-receptors. Antibodies target and bind the primary receptor binding site on the virus surface, inducing a conformational change that facilitates binding to a co-receptor and promotes membrane fusion95(Fig. 5C). EV-A71 can use several attachment receptors to facilitate viral entry in addition to SCARB296, highlighting this mechanism as a potential mechanism of ADE in EVs that warrants further investigation.

Disentangling the epidemiological data for evidence of ADE during EV-A71 infection is challenging due to limited EV-A71 surveillance programs and overlapping clinical presentations with other viruses. Nevertheless, evidence from school-aged children in Taiwan suggests that ADE could contribute to disease severity, as children infected with EV-A71 were more likely to develop symptomatic infection with a subsequent heterotypic EV infection than their sero-naïve classmates97. In addition, as mentioned above, the rise in disease severity at six to eleven months coincides with the decline in maternal antibodies3, and it has been proposed that this drop in antibody concentration could increase infectivity98. Of note, in this situation, the increased severity may also result from decreased protection by maternal antibodies.

Experimental data also suggest that ADE can result from secondary EV infection. Indeed, EV-A71-seropositive immune sera have demonstrated the capacity to induce increased EV-A71 infection of primary monocytes98. Similarly, antibodies present in diluted human intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), which consists of pooled purified polyvalent IgG from multiple donors that could have varying levels of anti-EV-A71 antibodies, can induce increased EV-A71 infection of monocytic cell lines87. This finding has potential clinical implications as IVIg is used to treat HFMD99. Neutralizing antibodies corresponding to circulating strains have been observed in IVIg99. Specifically, in China, where EV-A71 is highly prevalent, IVIg contains high titers of anti-EV-A71 nAbs100. However, in areas where seroprevalence is low, IVIg could contain subneutralizing levels of Abs that would facilitate ADE.

ADE has been reported in murine models, where primary infection with EV-A71 strains AH08/06 or Taiwan/4643/98 followed by subsequent infection with a heterotypic strain, either AH08/09 or MP4, respectively, resulted in lethal infection87,101. Cao et al. suggested that IgG subclasses may differentially drive ADE of EV-A71 infection, where IgG1 has the highest neutralizing activity in vitro, followed by IgG2, while IgG3 shows no neutralizing activity and is linked with enhanced infection102. The role of complement-dependent ADE in EV infections remains to be investigated and is of great interest given that EVs elicit a robust, rapid IgM response upon infection, as mentioned in the previous section on EV-A71 infection and humoral response (Fig. 3)61. Clinical evidence associating severe EV-A71 disease and ADE in humans warrants further investigation.

ADE has additionally been reported for related Enterovirus alphacoxsackie species and, to a greater extent, Enterovirus betacoxsackie species (previously referred to as Enterovirus B species). CVB-induced ADE has been observed in mice103. Incubation of coxsackievirus B4 (CVB4) with the IgG-enriched fraction of sera from Swiss albino mice previously exposed to epitope E2 on the VP1 developed increased vial titers during infection in mice104. Kishimoto et al. showed that mice who developed sub-neutralizing antibodies following primary infection with CVB3 experienced enhanced severity of secondary infection with CVB3, characterized by myocarditis, compared to mice with neutralizing antibodies or no antibodies105. Furthermore, they found that enhanced infection was Fc-dependent, as the Fab region alone was insufficient to enhance infection in vitro. In line with these observations, Yu et al. showed that primary infection with CVB2 followed by secondary infection with a heterotypic CVB3 virus in mice resulted in increased viral RNA load, tissue inflammation and necrosis in the heart and pancreas compared to CVB2 or CVB3 alone106.

Interestingly, incubation of sera from children previously infected with coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) resulted in increased production of interferon-alpha (IFN-α) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in vitro compared with sera from uninfected children107. Whether this translates into a clinically relevant phenotype remains to be demonstrated. Likewise, CVB4 pre-incubated with patient sera elicited a robust IFN-α response in infected PBMCs compared to CVB4 alone108,109,110, implicating that intrinsic ADE pathways could be involved.

As mentioned, neutralization can result from antibody-induced viral aggregation, as shown for poliovirus72. But, in some conditions, viral aggregates may improve infection by increasing the multiplicity of infection and favoring productive replication. Antibody Fab1-IA was found to neutralize rhinovirus weakly but induced virus aggregation111. Interestingly, while a Fab1-IA antibody-to-virus ratio between 10 and 100 led to virus neutralization, increasing the ratio to 1000 or higher resulted in an increase in the number of infectious virions collected. This suggests that a higher concentration of Fab1-IA may enhance viral infection.

Taken together, these experimental data suggest the existence of ADE in EV. Accordingly, they highlight a potentially deleterious impact of using low doses of IVIg to treat patients with severe EV-related disease, which is currently the only available therapy for severe disease and is further discussed in section 10 of this review. Indeed, a meta-analysis shows that higher doses of IVIg have a better prognosis112, yet whether this is due to insufficient antibody titers or ADE remains to be investigated. Moreover, understanding the interplay between immunity and pathogenicity in the context of multiple circulating EV strains is critical when addressing vaccine design, development, and implementation.

Vaccine

There is an urgent and unmet need to develop and implement EV vaccines to mitigate the disease burden. Several EV-A71 vaccine strategies are currently being explored (Fig. 6). The vaccine development approach that has proven to be the most successful thus far, particularly in China where three vaccines have been licensed, is the use of inactivated vaccines63,113,114,115,116. Nevertheless, pre-clinical development of EV-A71 vaccines using alternative approaches, including, live attenuated vaccines (LAV)117, virus-like particles (VLPs)118, DNA119, microRNA120, and protein-based121 vaccines is underway. Interestingly, even though EV-A71 is transmitted through the fecal-oral route, the commercially available EV71 vaccines and most vaccine candidates under development are administered via intramuscular injection63,113,114,115,116,117,118,119. In fact, only one study employs oral administration for vaccination122. Regardless of the vaccine approach, it is crucial to understand the immune correlates of protection, identify the relevant strains circulating in the community, and comprehend how immunity influences either protection or potential disease enhancement. Moreover, given that the highest burden of disease occurs in children under 2 years old, it is essential for an EV-A71 vaccine candidate to present an excellent safety profile. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of all EV-A71 vaccines, detailing those currently approved and available for use, as well as those in various stages of pre-clinical and clinical development.

Representation of vaccine (black arrows) and immunotherapy (gray arrows) strategies for mitigating severe EV-A71 infection. Dashed arrows highlight vaccines in pre-clinical development, while filled arrows indicate vaccine candidates that have completed phase III clinical trials and/or are approved. The image was made using Biorender.

Three licensed inactivated EV-A71 subgenogroup C4 vaccines, produced by Sinovac Biotech Ltd, Beijing Vigoo Biological, and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS), are available in China80 (Table 1, Fig. 6). Randomized control trials of these three inactivated vaccines report a seroconversion rate of 87.6–100% and a greater than 90% efficacy in preventing HFMD for infants 6–35 months old63,113,114,115,116. The vaccine efficacy is comparable between the three vaccines, with Sinovac Biotech Ltd slightly outperforming the other two in clinical trials. A systematic review of EV-A71 vaccine efficacy estimated that a single dose of any of the inactivated vaccines available in China prevents 66.9% of infections, while two doses result in an 84.2% vaccine efficacy123. Moreover, seropositivity was maintained for the two-year follow-up period of the CAMS114 and Beijing Vigoo Biological124 clinical trials and the five-year follow-up study for the Sinovac Biotech Ltd vaccine115.

Since the introduction of inactivated vaccines in China in 2016, post-marketing studies have been conducted to determine real-world efficacy. Notably, EV-A71 vaccine coverage varies with values of 24% in Ningbo to 44% in Zhejiang, China125,126. Encouragingly, a meta-analysis suggested that a vaccine coverage of over 20% reduces the relative risk of EV-A71 transmission by ~10%, although the risk remains higher with increasing population density127. The results of a modeling study based on data collected from suspected HFMD cases in Zhejiang between 2016 and 2019 estimated that vaccinating 55% of children under the age of 5 years is sufficient to prevent epidemics126. The collective findings from these studies indicate that 100% vaccine coverage may not be a prerequisite for preventing outbreaks and suggest that targeted vaccination efforts in children under five years old can contribute significantly to controlling EV-A71 transmission.

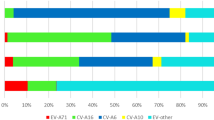

Indeed, post-marketing studies indicate that EV-A71 infections are less common (3.4–7.2% versus over 10%) in regions where an inactivated EV-A71 vaccine was implemented, however, the identity of the subgenogroups observed since vaccine implementation was not reported128. In contrast, non-EV-A71 strains, particularly CVA6 and CVA16, have increased in incidence, now accounting for 77.2–85.8% of HFMD infections compared to approximately 15% before the rollout of the EV-A71 vaccine129. This is not surprising, as post-vaccination studies indicate that the EV-A71 inactivated vaccine does not confer cross-protection against CVA strains, highlighting the need for multivalent vaccines130. However, the introduction of the inactivated EV-A71 vaccines may not be solely responsible for an increase in CVA infections, as countries that have not implemented EV-A71 vaccines have also experienced a rise in CVA strains in recent years131. The dominant circulating EVs change frequently and vary by season and region129, making it challenging to determine which subgenogroups to include in such a vaccine. Finally, the ability of the subgenogroup C4 vaccine to offer long-term protection against other EV-A71 genogroups in humans is not known. In vitro data suggest that the approved inactivated vaccines offer cross-protection against EV-A71 subgenogroups A, B3-5, and C1-563,113,114,115,116,124,132,133. However, the C1 subgenogroup emerged in Guangdong, China, between 2018 and 2019134, 2 years after vaccination campaigns using the C4 inactivated EV-A71 vaccines started135, suggesting that these vaccines may not provide cross-protection against other EV-A71 subgenogroups.

While long-term vaccine efficacy remains under assessment, the safety profile of these vaccines is promising. The occurrence of adverse events following vaccination with the Vigoo Biological or Sinovac Biotech Ltd vaccine did not differ from the placebo group63,116, highlighting that these vaccines have excellent safety profiles. Mild adverse events such as fever along with pain, swelling, and redness at the injection site were reported in the first week following vaccination with the CAMS vaccine113. Encouragingly, no novel genetic mutations have been observed in circulating EV-A71 strains following the introduction of an inactivated EV-A71 vaccine in China in 2016 by the CAMS136, indicating that it has not led to the emergence of new genetic mutations in the virus, bolstering support that these vaccines are safe.

More recently, a formalin-inactivated EV-A71 subgenogroup B4 with alum adjuvant (EV-71vac) has completed phase III clinical trials in Taiwan and Vietnam (NCT01268787, NCT02200237, NCT03865238)64,137,138. In phase I clinical trials, 95% of adults vaccinated with EV-71vac had a greater than fourfold increase in neutralizing antibodies against baseline with no significant boost following a second dose137, indicating that one dose may be sufficient. Critically, approximately 85% of vaccine recipients demonstrated cross-neutralizing antibodies against EV-A71 subgenogroup B1, B5, and C4A, while a limited number of vaccinees (20%) additionally exhibited neutralizing efficacy against subgenogroup C4B and related EV CVA16. The vaccine showed a good safety profile, with no reports of severe adverse events during the follow-up period138,139. The phase II clinical trial in children aged 2 months to 11 years provided evidence that two vaccine doses of 5 μg were safe, elicited neutralizing antibodies that last for at least 1 year post-vaccination, and cross-neutralize subgenogroups B5, C4, and C5138. Notably, this vaccine was effective alongside the routine childhood immunization schedules against measles, mumps, rubella, Japanese encephalitis, poliovirus, Hepatitis B, Meningococcal A, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and tuberculosis138. Phase III clinical trials in children aged two to 11 months highlighted a vaccine efficacy of 96.8% against EV-A71-associated disease in vaccinees compared with placebo64. Long-term efficacy remains to be evaluated.

Additional inactivated bivalent EV-A71 (subgenogroup B4/C4)/CVA16 and trivalent EV-A71 (subgenogroup B2)/CVA16/CVA6 vaccines are under pre-clinical investigation with contrasting results140,141,142. Interestingly, Yi et al. observed that neutralizing antibodies against CVA16 and EV-A71 were generated following vaccination with inactivated vaccines and were sufficient to protect against subsequent challenge140. However, Lin et al. did not detect neutralizing antibodies against CVA16 following bivalent vaccination in mice141. The inactivated trivalent EV-A71/CVA16/CVA6 elicited neutralizing antibodies against all three viruses and protected mice from lethal challenge with EV-A71, CVA16, and CVA6142. Of note, only the highest doses tested in the studies (1 µg141 and 100 ng140) of this non-adjuvanted vaccine induced an immune response in all mice. Inactivated vaccines can induce weaker antibody responses that decline shortly after vaccination and require multiple doses to maintain long-term immunity; therefore, long-term follow-up studies are encouraged. Moreover, inactivated vaccines risk stimulating a weak T-cell response due to the limited exposure to antigen116. However, inactivated viral vaccines are generally considered safe as there is no viral replication and therefore no risk of introducing virulent mutations.

VLPs and peptide vaccines are under development against EV-A71 and CVA16, with promising results in early animal studies121. VLPs are non-infectious particles that mimic the structure of viruses but lack genetic material. Similar to inactivated vaccines, VLP and protein-based vaccines are considered safe, with no risk of mutation. In addition, VLPs induce stronger human and cellular immune responses compared to inactivated vaccines143. Notably, EV-A71 VLP vaccines show long-lasting cross-protection with other EV-A71 subgenogroups118,144. Chimeric EV VLP vaccines can offer cross-protection against multiple EVs144. The chimeric VLP candidate, CHiEV-A71, is made of the EV-A71 backbone with an SP70 epitope substitution from CVA16, which spans amino acids 208-222 next to the GH loop, one of the components of the SCARB2 binding site. CHiEV-A71 elicited neutralizing antibodies against EV-A71 and CVA16 and protected neonatal mice from lethal challenge through passive immune transfer of antibodies collected from immunized mice145. Whether these antibodies protect against subsequent infection in vitro, neutralization assays, and in vivo remains to be determined.

Recombinant polypeptides have been explored as vaccine candidates, although they remain in the pre-clinical phase. Recombinant proteins, like VLPs, are generally considered safe and carry no risk of mutation. Importantly, several of these recombinant polypeptides protected mice from lethal infection and induced both B and T-cell responses146,147,148. Recombinant polypeptides have also been demonstrated to confer cross-protection against multiple genotypes. Specifically, peptide P25, derived initially from the VP1 of EV-D68, inhibited infection with EV-A71 subgenogroup C4 and EV-D68 in vitro via competitive inhibition of EV with heparan sulfate binding149. Finally, an EV-A71 vaccine approach introduced the VP1 gene fused to a mitochondrial sorting signal into a transgenic tomato plant122. The plant was then administered orally to BALB/c mice, who developed anti-EV-A71 fecal IgA and serum IgG. While it remains to be seen whether this vaccine offers protection against viral challenge, the administration strategy of the vaccines aligns with that of natural infection, and testing for the presence of neutralizing IgA adds valuable insight regarding vaccine-induced immunity, which is lacking in other studies.

Several research groups have explored additional vaccine strategies. A vaccine, EV71-VP4, composed of the first 20 amino acids on the N-terminal of the VP4 protein (VP4N20) fused with the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), formed VLPs in E. coli that were able to elicit an antibody response against the VP4N20 epitope in mice150. Moreover, the transfer of the anti-EV71-VP4 subgenogroup C4 sera to neonatal mice was sufficient to rescue 90% of the pups from lethal challenge with EV-A71 subgenogroup C4150. Similarly, an E1/2-HBc vaccine was developed using the E1, E2, or both epitopes previously mentioned151(Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 1). All vaccine candidates elicited neutralizing antibodies in mice, but only E2-HBc immunization prevented lethal outcomes after infection with EV-A71 (subgenogroup C4) and CVA16151. Another attractive pre-clinical vaccine candidate includes a DNA-based tetravalent vaccine, VP1me, that produces a complete EV-A71 VP1 protein with six reported neutralizing B-cell epitopes of four EVs, including EV-A71, CVA16, CVA10, and CVA6), was generated and elicited antibody and T-cell responses in mice119. Interestingly, the six epitopes included previously identified epitopes from mouse sera, namely VP2-28, VP4N20, and VP3-knob152,153. The vaccine also includes one CVA6 VP1 epitope, one CVA16 VP1 epitope, and a CVA10 VP2 epitope to expand the efficacy of this vaccine to other clinically relevant EVs119.

Alternatively, LAVs for EV-A71 are being explored154. LAVs offer the advantage of eliciting strong long-lasting humoral and cellular responses155. However, as replicating viruses, there is a risk of the emergence of novel, potentially virulent mutations. The furthest candidate along the pre-clinical journey is a bivalent LAV vaccine against EV-A71 and CVA16, which was shown to be safe and immunogenic in Rhesus macaques through intramuscular injection, although efficacy studies are still pending117 (Table 1). It would be interesting to assess whether oral administration rather than intramuscular injection could impact the safety and immunogenicity profile of the LAV, as this is closer to the transmission route of natural infection. Another strategy developed by Yee et al.120 involved introducing micro-RNA let-7a and miR-124a target sequences into an EV-A71 strain of the B4 subgenogroup with an 11 base pair deletion in the 5’ non-translating region and a G64R mutation in the polymerase120. The G64R mutation has been shown to enhance polymerase fidelity156, contributing to an attenuated phenotype in mice157,158, thereby supporting the safety profile of the vaccine (Table 1). This strategy was adapted from a previously developed live attenuated poliovirus vaccine, including micro-RNA let-7a and miR-124a159. The let-7a and miR-124a target sequences are specific to neuronal tissue, and their incorporation into live attenuated EV-A71 vaccine candidates blocks viral replication in central nervous tissues, restricting host tropism, preventing neurological complications, and protecting four-week-old mice from developing hind limb paralysis159.

There are several crucial aspects to consider when designing, developing, and implementing an EV vaccine. Selecting which genotype or genogroup to include in a vaccine is critical. Multiple EV strains can circulate simultaneously in the same region, and active surveillance is required to stay informed. Therefore, it is essential to design a vaccine targeting a circulating genogroup, while keeping in mind that the strains present in the community are subject to change and that vaccines should be updated accordingly in the absence of cross-protection. In this light, a vaccine offering cross-protection across genogroups of EV-A71 or across different EV-A species is desirable, although the high number of distinct EV types complicates the task. Incomplete protection raises concerns about promoting ADE. Ideally, epitopes known to elicit potent cross-neutralizing antibodies should be included, while those less immunogenic or inducing non-neutralizing or sub-neutralizing antibodies, potentially associated with ADE, should be avoided, highlighting the need to characterize EV epitopes further. In parallel with vaccine development, the therapeutic potential of monoclonal antibodies warrants careful consideration, especially as this strategy may help circumvent non-specific or suboptimal immune responses.

Monoclonal antibody therapy

Passive immunization using IVIg from pooled polyclonal sera is used clinically to treat EV-A71 (Fig. 6). However, this approach has several limitations, including batch-to-batch variation, potential transmission of blood-borne pathogens, and sub-neutralizing antibodies. Nevertheless, this approach does underscore that passive antibody transfer can protect against severe disease25. Employing monoclonal antibodies can circumvent several of the challenges IVIg poses and could provide an alternative to protecting against EV pathology.

Notably, mAbs can act prophylactically or post-infection by neutralizing invading viruses, highlighting them as a potential approach for preventive or therapeutic treatment. While mAbs have been approved as prophylaxis and treatment for other viral infections160, anti-EV-A71 mAbs remain in the pre-clinical phase and are summarized in Table 2. Mechanistically, most mAbs neutralize the virus by inhibiting viral entry17,79,161, while other mAbs mitigate infection via alternative targets in the virus life cycle162. Specifically, mAb 10D3 that targets a conformational epitope on the knob region of VP3, protected two-week-old AG129 mice from developing limb paralysis when administered prophylactically via intraperitoneal injection and neutralized all EV-A71 genogroups in vitro17. Additionally, mAbs CT11F9163, BB145 IgG2a79, and h1A6.2161 target VP2 and protected 100% of mice from lethal challenge when administered intraperitoneally post-infection. Engineered broadly neutralizing mAb Bs(scFv)4-IgG-1 was 100% effective in protecting against lethal EV-A71 and CVA16 infection164. Additionally, mAbs 22 and 24 can bind to EV-A71 subgenogroups B5, C2, and C4 but vary in binding activity against subgenogroup B4 and do not interact with subgenogroup B1165. As mAb 22 and 24 were originally isolated and assessed as diagnostic tools, it remains to be seen whether they would effectively prevent disease in an in vitro model system165. Alternatively, mAb JL2 binds human SCARB2, indirectly inhibiting EV-A71 infection in vitro166. However, JL2 remains to be tested in vivo. On the other hand, mAb 3A12 and 3A10 target the 3DPOL (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) of EV-A71 subgenogroup A and offer partial protection against lethal disease in neonatal mice challenged with the mouse adapted virus strain (MAV-VR), originally isolated from a fatal pediatric patient167, which carries the same epitope sequence at the 3DPOL as the of EV-A71 subgenogroup A strain used in in vitro neutralization experiments162.

Importantly, it seems that the antibody isotype, rather than the epitope alone, influences the level of protection against infection or severe disease. A monoclonal IgM, mAB51, targeting the VP1 from position 215 to 219 next to the GH loop, was able to protect AG129 mice from lethal challenge with EV168. Interestingly, a monoclonal IgG, mAB53, targeting the same epitope was insufficient to protect mice from challenge168, highlighting the need to investigate EV humoral immunity further. Similarly, a comparison of chimeric antibodies 20-IgM and 20-IgG shows that 20-IgM blocks virus entry, uncoating, and RNA release more efficiently than 20-IgG169. Both chimeric antibodies were based on the mouse monoclonal IgM M20, an antibody derived from co-immunization of 6-week-old BALB/c mice with EV-A71 and CVA16, which targets the GH loop of the VP1 and has shown to efficiently neutralize multiple EV-A71 genogroups in vitro170. Moreover, 20-IgM protected 100% of mice from lethal challenge with EV-A71, CVA6, CVA10, and CVA16, whereas IgG only protected 100%, 73%, 33%, and 53% of mice from the respective viruses. This study highlights that IgM could offer broader protection against members of the Enterovirus alphacoxsackie species, given the rise of CVA infections129,131, would be an immense asset to have as a therapeutic option.

However, mAbs are short-lived and do not offer long-term protection against infection. Furthermore, as with most monotherapies, there is a risk of engendering escape mutants17. This could be addressed by creating mAb cocktails that function similarly to passive transfer of polyclonal sera like IVIg, with the added advantage of batch-to-batch consistency, no risk of blood-borne pathogen contamination, or introduction of non-neutralizing antibodies that could lead to ADE. Unfortunately, monoclonals are generally more expensive than small molecules171, yet a number of mAb have been approved, including Palivizumab for Respiratory Syncytial virus172 and Inmazeb for Ebola virus173. Monoclonal antibody therapies represent a promising adjunct to existing infection control and treatment strategies. Nevertheless, the inherent limitations of this therapeutic approach reinforce the necessity of a public health strategy that includes robust surveillance, anticipatory vaccine design, and a toolkit of therapeutic options to address the evolving landscape of circulating enteroviruses.

Concluding remarks

The interplay between population immunity and locally circulating EV strains is highly dynamic. Vaccination campaigns further shape the landscape of circulating EV diversity and can select strains that are able to evade vaccine-induced immunity136. Therefore, there is a need to improve surveillance of EVs to ensure that appropriate vaccines are introduced and to forecast which strains are becoming more prevalent and will require vaccination in the future. EV transmission is sensitive to local weather patterns, and the potential effects of climate change on EV distribution and seasonality warrant careful monitoring to prepare for future outbreaks. Moreover, the threat of recombination between different EV strains, which could generate more virulent strains and complicate vaccine efficacy174, along with the potential risk of ADE, underscores the need for robust EV surveillance systems.

Correlates of protection need to be better defined to evaluate next-generation EV-A71 vaccines. Cross-protection following primary EV infection is possible175, but it is clinically rare, suggesting multiple infections are required to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies. This natural history, compounded by multiple antigenically similar serotypes co-circulating in any given environment and the absence of long-lasting immunity, raises concerns about ADE. Furthermore, long-term vaccine protection warrants attentive monitoring, as waning vaccine-induced immunity could increase susceptibility to ADE. Both in vitro and in vivo studies on ADE have suggested that ADE-mediated infections with EVs are possible, but further clinical evidence is needed to align the experimental evidence with epidemiological data.

Moreover, the role of IgA in response to EV infections warrants further investigation. EVs are transmitted via the fecal-oral or respiratory route, both of which entail initial infection in the mucosa, where mucosal immunity plays a critical role. Wang et al. have developed a test to diagnose EVs in children based on IgA from saliva51, which could be a valuable tool in monitoring IgA response in primary and secondary infections. IgA mitigated the impact of FcγR-mediated ADE in dengue by competing with IgG for antigen binding176. Whether anti-EV IgA plays a protective role in secondary infection remains to be assessed. However, of the 28 monoclonal IgA and 37 monoclonal IgM generated based on plasmablast B-cell receptor sequences by You et al., six IgM antibodies neutralized EV-A71, while no IgA antibodies demonstrated neutralizing capabilities82.

Briefly, another factor that merits consideration when discussing EV vaccination is the possibility of engendering autoantibodies. EVs have been linked to the onset or progression of autoimmunity towards islet cells and, therefore, promote type one diabetes mellitus (T1DM) in genetically predisposed individuals177. T1DM has been associated with CVB, which persists in pancreatic ductal and β-cells, a connection supported by epidemiology and clinical studies177,178. Although no association has been observed with EV-A71 vaccination or natural infection, the diabetes-associated tyrosine phosphatase called islet cell antigen-related PTP (IAR) shares sequence homologies with VP1 and its precursor VP0179, raising potential concerns.

The global health burden of EVs remains to be entirely determined. EV outbreaks have been witnessed in the United States of America10, Europe180, and Asia Pacific region35. The genetic diversity, varied disease presentation, and geographical distribution of EVs make dissecting the interplay between immunity and pathogenesis challenging and complex. Additionally, the impact of climate change and vaccination campaigns could further shift EV epidemiology. Research on the dynamics of immunity and multiple EV infections is required to inform the development of next-generation, combined EV vaccines. Moreover, coordinated surveillance, particularly of potential zoonotic reservoirs, and preparedness efforts are essential to preventing future EV outbreaks and epidemics.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Brouwer, L., Moreni, G., Wolthers, K.C. & Pajkrt, D. World-wide prevalence and genotype distribution of enteroviruses. Viruses 13, 434 (2021).

Royston, L. & Tapparel, C. Rhinoviruses and respiratory enteroviruses: not as simple as ABC. Viruses 8, 16 (2016).

Xie, Z., Khamrin, P., Maneekarn, N. & Kumthip, K. Epidemiology of enterovirus genotypes in association with human diseases. Viruses 16, 1165 (2024).

Tapparel, C., Siegrist, F., Petty, T. J. & Kaiser, L. Picornavirus and enterovirus diversity with associated human diseases. Infect. Genet. Evol. 14, 282–293 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. A novel subgenotype C6 Enterovirus A71 originating from the recombination between subgenotypes C4 and C2 strains in mainland China. Sci. Rep. 12, 593 (2022).

Chan, Y. F., Sam, I. C. & AbuBakar, S. Phylogenetic designation of enterovirus 71 genotypes and subgenotypes using complete genome sequences. Infect. Genet. Evol. 10, 404–412 (2010).

Aswathyraj, S., Arunkumar, G., Alidjinou, E. K. & Hober, D. Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD): emerging epidemiology and the need for a vaccine strategy. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 205, 397–407 (2016).

Huang, K. A. Structural basis for neutralization of enterovirus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 51, 199–206 (2021).

Kok, C. C., Phuektes, P., Bek, E. & McMinn, P. C. Modification of the untranslated regions of human enterovirus 71 impairs growth in a cell-specific manner. J. Virol. 86, 542–552 (2012).

Du, J. et al. Analysis of enterovirus 68 strains from the 2014 North American outbreak reveals a new clade, indicating viral evolution. PLoS ONE 10, e0144208 (2015).

Huang, K. A. et al. Structural and functional analysis of protective antibodies targeting the threefold plateau of enterovirus 71. Nat. Commun. 11, 5253 (2020).

Plevka, P., Perera, R., Cardosa, J., Kuhn, R. J. & Rossmann, M. G. Crystal structure of human enterovirus 71. Science 336, 1274 (2012).

Dang, M. et al. Molecular mechanism of SCARB2-mediated attachment and uncoating of EV71. Protein Cell 5, 692–703 (2014).

Ku, Z. et al. Single Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies targeting the VP1 GH loop of enterovirus 71 inhibit both virus attachment and internalization during viral entry. J. Virol. 89, 12084–12095 (2015).

Zhu, L. et al. Neutralization mechanisms of two highly potent antibodies against human enterovirus 71. mBio 9, e01013–18 (2018).

Lyu, K. et al. Crystal structures of enterovirus 71 (EV71) recombinant virus particles provide insights into vaccine design. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 3198–3208 (2015).

Kiener, T. K., Jia, Q., Meng, T., Chow, V. T. & Kwang, J. A novel universal neutralizing monoclonal antibody against enterovirus 71 that targets the highly conserved “knob” region of VP3 protein. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2895 (2014).

Baggen, J., Thibaut, H. J., Strating, J. & van Kuppeveld, F. J. M. The life cycle of non-polio enteroviruses and how to target it. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 368–381 (2018).

Yamayoshi, S., Fujii, K. & Koike, S. Receptors for enterovirus 71. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 3, e53 (2014).

Yuan, M. et al. Enhanced human enterovirus 71 infection by endocytosis inhibitors reveals multiple entry pathways by enterovirus causing hand-foot-and-mouth diseases. Virol. J. 15, 1 (2018).

Hussain, K. M., Leong, K. L., Ng, M. M. & Chu, J. J. The essential role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the infectious entry of human enterovirus 71. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 309–321 (2011).

Diarimalala, R. O., Hu, M., Wei, Y. & Hu, K. Recent advances of enterovirus 71 [Formula: see text] targeting Inhibitors. Virol. J. 17, 173 (2020).

Thompson, S. R. & Sarnow, P. Enterovirus 71 contains a type I IRES element that functions when eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4G is cleaved. Virology 315, 259–266 (2003).

Tan, C. W., Lai, J. K., Sam, I. C. & Chan, Y. F. Recent developments in antiviral agents against enterovirus 71 infection. J. Biomed. Sci. 21, 14 (2014).

Wei, Y. et al. Recent advances in enterovirus A71 infection and antiviral agents. Lab. Invest. 104, 100298 (2024).

Horwood, P. F. et al. Seroepidemiology of Human Enterovirus 71 Infection among Children, Cambodia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22, 92–95 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. Seroepidemiology of enterovirus A71 infection in prospective cohort studies of children in southern China, 2013–2018. Nat. Commun. 13, 7280 (2022).

Hagiwara, A., Tagaya, I. & Komatsu, T. Seroepidemiology of enterovirus 71 among healthy children near Tokyo. Microbiol. Immunol. 23, 121–124 (1979).

Ooi, M. H. et al. Human enterovirus 71 disease in Sarawak, Malaysia: a prospective clinical, virological, and molecular epidemiological study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44, 646–656 (2007).

Ooi, E. E., Phoon, M. C., Ishak, B. & Chan, S. H. Seroepidemiology of human enterovirus 71, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 995–997 (2002).

Lin, T. Y., Twu, S. J., Ho, M. S., Chang, L. Y. & Lee, C. Y. Enterovirus 71 outbreaks, Taiwan: occurrence and recognition. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9, 291–293 (2003).

Linsuwanon, P. et al. Epidemiology and seroepidemiology of human enterovirus 71 among Thai populations. J. Biomed. Sci. 21, 16 (2014).

Tran, C. B. et al. The seroprevalence and seroincidence of enterovirus71 infection in infants and children in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. PLoS ONE 6, e21116 (2011).

Shi, Y., Chen, P., Bai, Y., Xu, X. & Liu, Y. Seroprevalence of coxsackievirus A6 and enterovirus A71 infection in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Virol. 168, 37 (2023).

Lee, J. T. et al. Enterovirus 71 seroepidemiology in Taiwan in 2017 and comparison of those rates in 1997, 1999 and 2007. PLoS ONE 14, e0224110 (2019).

Chang, L. Y. et al. Risk factors of enterovirus 71 infection and associated hand, foot, and mouth disease/herpangina in children during an epidemic in Taiwan. Pediatrics 109, e88 (2002).

Ang, L. W. et al. Epidemiology and control of hand, foot and mouth disease in Singapore, 2001-2007. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 38, 106–112 (2009).

Riller, Q., Schmutz, M., Fourgeaud, J., Fischer, A. & Neven, B. Protective role of antibodies in enteric virus infections: Lessons from primary and secondary immune deficiencies. Immunol. Rev. 328, 243–264 (2024).

Kassab, S. et al. Fatal case of enterovirus 71 infection and rituximab therapy, france, 2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 1345–1347 (2013).

Halliday, E., Winkelstein, J. & Webster, A. D. Enteroviral infections in primary immunodeficiency (PID): a survey of morbidity and mortality. J. Infect. 46, 1–8 (2003).

Ahmed, R. et al. Enterovirus 71 meningoencephalitis complicating rituximab therapy. J. Neurol. Sci. 305, 149–151 (2011).

Weng, K. F. et al. Variant enterovirus A71 found in immune-suppressed patient binds to heparan sulfate and exhibits neurotropism in B-cell-depleted mice. Cell Rep. 42, 112389 (2023).

Puenpa, J., Wanlapakorn, N., Vongpunsawad, S. & Poovorawan, Y. The history of enterovirus A71 outbreaks and molecular epidemiology in the Asia-Pacific region. J. Biomed. Sci. 26, 75 (2019).

Xing, W. et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China, 2008-12: an epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 308–318 (2014).

Guo, T. et al. Seasonal Distribution and Meteorological Factors Associated with Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease among Children in Xi’an, Northwestern China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102, 1253–1262 (2020).

Zeng, M. et al. Seroepidemiology of Enterovirus 71 infection prior to the 2011 season in children in Shanghai. J. Clin. Virol. 53, 285–289 (2012).

Ang, L. W. et al. The changing seroepidemiology of enterovirus 71 infection among children and adolescents in Singapore. BMC Infect. Dis. 11, 270 (2011).

Harvala, H. et al. Recommendations for enterovirus diagnostics and characterisation within and beyond Europe. J. Clin. Virol. 101, 11–17 (2018).

Organization, T.W.H. A Guide to Clinical Management and Public Health Response for Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD), (World Health Organization, Manila, Philippines, 2011).

Zhou, Y. et al. Diagnostic performance of different specimens in detecting enterovirus A71 in children with hand, foot and mouth disease. Virol. Sin. 38, 268–275 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. A novel method to diagnose the infection of enterovirus A71 in children by detecting IgA from saliva. J. Med. Virol. 92, 1059–1064 (2020).

Nguyen, T. H. T. et al. Methods to discriminate primary from secondary dengue during acute symptomatic infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 375 (2018).

Ooi, M. H. et al. Evaluation of different clinical sample types in diagnosis of human enterovirus 71-associated hand-foot-and-mouth disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 1858–1866 (2007).

Ooi, M. H., Wong, S. C., Lewthwaite, P., Cardosa, M. J. & Solomon, T. Clinical features, diagnosis, and management of enterovirus 71. Lancet Neurol. 9, 1097–1105 (2010).

McMinn, P. C. An overview of the evolution of enterovirus 71 and its clinical and public health significance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26, 91–107 (2002).

Ma, E. et al. Estimation of the basic reproduction number of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 in hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 30, 675–679 (2011).

Shen, J. et al. Relationship between serologic response and clinical symptoms in children with enterovirus 71-infected hand-foot-mouth disease. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8, 11608–11614 (2015).

Cheng, H. Y. et al. The correlation between the presence of viremia and clinical severity in patients with enterovirus 71 infection: a multi-center cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 417 (2014).

Qiu, Q. et al. Kinetics of the neutralising antibody response in patients with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by EV-A71: a longitudinal cohort study in Zhengzhou during 2017-2019. EBioMedicine 68, 103398 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Comparison of neutralizing antibody response kinetics in patients with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by coxsackievirus A16 or enterovirus A71: a longitudinal cohort study of Chinese Children, 2017–2019. J. Immunol. 209, 280–287 (2022).

Xu, F. et al. Performance of detecting IgM antibodies against enterovirus 71 for early diagnosis. PLoS ONE 5, e11388 (2010).

Chen, K., Magri, G., Grasset, E. K. & Cerutti, A. Rethinking mucosal antibody responses: IgM, IgG and IgD join IgA. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 427–441 (2020).

Zhu, F. et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an enterovirus 71 vaccine in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 818–828 (2014).

Nguyen, T. T. et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an inactivated, adjuvanted enterovirus 71 vaccine in infants and children: a multiregion, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 399, 1708–1717 (2022).

Sun, S. et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of an EV71 virus-like particle vaccine against lethal challenge in newborn mice. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 11, 2406–2413 (2015).

Lim, P. Y. et al. Immunogenicity and performance of an enterovirus 71 virus-like-particle vaccine in nonhuman primates. Vaccine 33, 6017–6024 (2015).

Seikrit, C. & Pabst, O. The immune landscape of IgA induction in the gut. Semin. Immunopathol. 43, 627–637 (2021).

Mathias, A. & Corthesy, B. N-Glycans on secretory component: mediators of the interaction between secretory IgA and gram-positive commensals sustaining intestinal homeostasis. Gut Microbes 2, 287–293 (2011).

Mbani, C. J. et al. Enterovirus antibodies: friends and foes. Rev. Med. Virol. 34, e70004 (2024).

Ye, X. et al. Structural basis for recognition of human enterovirus 71 by a bivalent broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005454 (2016).

Plevka, P. et al. Neutralizing antibodies can initiate genome release from human enterovirus 71. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2134–2139 (2014).

Thomas, A. A., Vrijsen, R. & Boeye, A. Relationship between poliovirus neutralization and aggregation. J. Virol. 59, 479–485 (1986).

Watkinson, R. E., McEwan, W. A., Tam, J. C., Vaysburd, M. & James, L. C. TRIM21 promotes cGAS and RIG-I sensing of viral genomes during infection by antibody-opsonized virus. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005253 (2015).

Du, R. et al. Non-neutralizing monoclonal antibody targeting VP2 EF loop of Coxsackievirus A16 can protect mice from lethal attack via Fc-dependent effector mechanism. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, 2149352 (2023).

Behzadi, M. A. et al. A cross-reactive mouse monoclonal antibody against rhinovirus mediates phagocytosis in vitro. Sci. Rep. 10, 9750 (2020).

Gao, F. et al. Enterovirus 71 viral capsid protein linear epitopes: identification and characterization. Virol. J. 9, 26 (2012).

Aw-Yong, K. L., Sam, I. C., Koh, M. T. & Chan, Y. F. Immunodominant IgM and IgG epitopes recognized by antibodies induced in enterovirus A71-associated hand, foot and mouth disease patients. PLoS ONE 11, e0165659 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Genome-wide linear B-cell epitopes of enterovirus 71 in a hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) population. J. Clin. Virol. 105, 41–48 (2018).

Xu, L. et al. Protection against lethal enterovirus 71 challenge in mice by a recombinant vaccine candidate containing a broadly cross-neutralizing epitope within the VP2 EF loop. Theranostics 4, 498–513 (2014).

Aw-Yong, K. L., NikNadia, N. M. N., Tan, C. W., Sam, I. C. & Chan, Y. F. Immune responses against enterovirus A71 infection: implications for vaccine success. Rev. Med. Virol. 29, e2073 (2019).

You, L. et al. Antibody signatures in hospitalized hand, foot and mouth disease patients with acute enterovirus A71 infection. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1011420 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Bioinformatics-based prediction of conformational epitopes for Enterovirus A71 and Coxsackievirus A16. Sci. Rep. 11, 5701 (2021).

Saarinen, N.V.V. et al. Multiplexed high-throughput serological assay for human enteroviruses. Microorganisms 8, 1426 (2020).

Vatti, A. et al. Original antigenic sin: a comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 83, 12–21 (2017).

Tsuchiya, H., Furukawa, M., Matsui, M., Katsuki, K. & Inouye, S. Original antigenic sin’ phenomenon in neutralizing antibody responses in children with enterovirus meningitis. J. Clin. Virol. 19, 205–207 (2000).

Han, J. F. et al. Antibody dependent enhancement infection of enterovirus 71 in vitro and in vivo. Virol. J. 8, 106 (2011).

Hawkes, R. A. Enhancement of the infectivity of arboviruses by specific antisera produced in domestic fowls. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 42, 465–482 (1964).

Halstead, S. B. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 60, 421–467 (2003).

Takada, A. & Kawaoka, Y. Antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infection: molecular mechanisms and in vivo implications. Rev. Med. Virol. 13, 387–398 (2003).

Shukla, R., Ramasamy, V., Shanmugam, R. K., Ahuja, R. & Khanna, N. Antibody-dependent enhancement: a challenge for developing a safe dengue vaccine. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 572681 (2020).

Narayan, R. & Tripathi, S. Intrinsic ADE: the dark side of antibody dependent enhancement during dengue infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 580096 (2020).

Thomas, S. et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) and the role of complement system in disease pathogenesis. Mol. Immunol. 152, 172–182 (2022).

Nicholson-Weller, A. & Klickstein, L. B. C1q-binding proteins and C1q receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11, 42–46 (1999).

Guillon, C., Schutten, M., Boers, P. H., Gruters, R. A. & Osterhaus, A. D. Antibody-mediated enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity is determined by the structure of gp120 and depends on modulation of the gp120-CCR5 interaction. J. Virol. 76, 2827–2834 (2002).

Hu, K., Onintsoa Diarimalala, R., Yao, C., Li, H. & Wei, Y. EV-A71 mechanism of entry: receptors/co-receptors, related pathways and inhibitors. Viruses 15, 785 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Structures of foot-and-mouth disease virus with neutralizing antibodies derived from recovered natural host reveal a mechanism for cross-serotype neutralization. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009507 (2021).

Wang, S. M. et al. Enterovirus 71 infection of monocytes with antibody-dependent enhancement. Clin. Vaccin. Immunol. 17, 1517–1523 (2010).

Coudere, K. et al. Neutralising antibodies against enterovirus and parechovirus in IVIG reflect general circulation: a tool for sero-surveillance. Viruses 13, 1028 (2021).

Cao, R. et al. Presence of high-titer neutralizing antibodies against enterovirus 71 in intravenous immunoglobulin manufactured from Chinese donors. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50, 125–126 (2010).

Chen, I. C., Wang, S. M., Yu, C. K. & Liu, C. C. Subneutralizing antibodies to enterovirus 71 induce antibody-dependent enhancement of infection in newborn mice. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 202, 259–265 (2013).

Cao, R. Y. et al. Human IgG subclasses against enterovirus Type 71: neutralization versus antibody dependent enhancement of infection. PLoS ONE 8, e64024 (2013).

Sauter, P. & Hober, D. Mechanisms and results of the antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infections and role in the pathogenesis of coxsackievirus B-induced diseases. Microbes Infect. 11, 443–451 (2009).

Elmastour, F. et al. Immunoglobulin G-dependent enhancement of the infection with Coxsackievirus B4 in a murine system. Virulence 7, 527–535 (2016).

Kishimoto, C., Kurokawa, M. & Ochiai, H. Antibody-mediated immune enhancement in coxsackievirus B3 myocarditis. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 34, 1227–1238 (2002).

Yu, J. Z. et al. Secondary heterotypic versus homotypic infection by Coxsackie B group viruses: impact on early and late histopathological lesions and virus genome prominence. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 8, 93–102 (1999).

Aswathyraj, S. et al. Serum-derived IgG from coxsackievirus A6-infected patients can enhance the infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with coxsackievirus A6. Microb. Pathog. 125, 7–11 (2018).

Chehadeh, W., Bouzidi, A., Alm, G., Wattre, P. & Hober, D. Human antibodies isolated from plasma by affinity chromatography increase the coxsackievirus B4-induced synthesis of interferon-alpha by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 82, 1899–1907 (2001).

Alidjinou, E. K., Sane, F., Engelmann, I. & Hober, D. Serum-dependent enhancement of coxsackievirus B4-induced production of IFNalpha, IL-6 and TNFalpha by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 5020–5031 (2013).

Morvan, C., Nekoua, M. P., Debuysschere, C., Alidjinou, E. K. & Hober, D. Antibody-dependent enhancement and neutralization against CVB4 investigated in vitro and in silico through an agent-based model. J. Med. Virol. 96, e29399 (2024).

Che, Z. et al. Antibody-mediated neutralization of human rhinovirus 14 explored by means of cryoelectron microscopy and X-ray crystallography of virus-Fab complexes. J. Virol. 72, 4610–4622 (1998).

Jiao, W. et al. The effectiveness of different doses of intravenous immunoglobulin on severe hand, foot and mouth disease: a meta-analysis. Med. Princ. Pract. 28, 256–263 (2019).

Li, R. et al. An inactivated enterovirus 71 vaccine in healthy children. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 829–837 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. Immunity and clinical efficacy of an inactivated enterovirus 71 vaccine in healthy Chinese children: a report of further observations. BMC Med. 13, 226 (2015).

Hu, Y. et al. Five-year immunity persistence following immunization with inactivated enterovirus 71 type (EV71) vaccine in healthy children: a further observation. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 14, 1517–1523 (2018).

Zhu, F. C. et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunology of an inactivated alum-adjuvant enterovirus 71 vaccine in children in China: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 381, 2024–2032 (2013).

Yang, T. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an experimental live combination vaccine against enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 in rhesus monkeys. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 16, 1586–1594 (2020).

Kim, H. J. et al. Efficient expression of enterovirus 71 based on virus-like particles vaccine. PLoS ONE 14, e0210477 (2019).