Abstract

This review outlines the fundamentals of photoelectrocatalysis (PEC) using BiVO4 as a promising photoelectrode for environmental applications. Key PEC factors—light absorption, semiconductor properties, potential, temperature, and pH—are discussed. BiVO4’s optical, structural, and stability traits are compared with other vanadates. Synthesis methods (electrodeposition, SILAR, sputtering, and others) and performance-enhancing strategies (doping, heterojunctions, high-exposed facets) are examined. BiVO4’s pollutant degradation pathway and dual-function PEC systems are explored, emphasizing the balance between properties for efficient energy conversion and environmental cleanup.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global increase in environmental contamination—driven by population growth, agricultural expansion, industrial activity, and poor waste management—has led to the widespread pollution of air1,2,3,4, soil5, surface water6,7, and groundwater8,9. Organic pollutants, including dyes, surfactants, plastics, compounds of emerging concern (CECs), and human waste, have accumulated in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, presenting critical challenges to environmental and public health. In response, significant research has been devoted to developing efficient methods for the degradation or removal of these persistent contaminants, particularly in aqueous environments10. Among the most effective technologies, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have gained prominence due to their ability to generate highly oxidizing reactive oxygen species (HOROS), which initiate complex oxidation cascades that break down organic molecules into less harmful or value-added products or mineralized forms11. Within this class, photoelectrocatalysis (PEC) has emerged as a promising approach for degrading recalcitrant organic compounds, offering enhanced performance through the combination of photocatalysis and electrochemical assistance. As shown in Fig. 1, research in PEC has rapidly expanded in recent years, with continuing growth anticipated.

A PEC system typically consists of a photoactive electrode (photoanode or photocathode), usually a semiconductor metal oxide, operated under an external bias potential or current12. Common materials for photoanode fabrication include TiO213, WO314, ZnO15, Cu2O16, CdS17, FeS17, Fe2O318, Bi2WO619, BiVO420, as well as perovskite-based oxides (ABO3)21,22. Among these, TiO2 has been extensively studied due to its non-toxicity and affordability. However, its photocatalytic activity is restricted to the ultraviolet region of the spectrum23, prompting the search for visible-light-photocatalytic alternatives. Bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) has gained considerable attention due to its relatively narrow bandgap (~2.4 eV) and visible-light photoactivity, which make it suitable for applications such as organic dye degradation and water splitting24,25. As illustrated in Fig. 1, BiVO4 has become one of the most widely studied materials in PEC research. Given that Earth receives approximately 8.6 × 104 TW year−1 of solar energy—vastly exceeding the ~13.2 TW consumed globally in 201926,27—PEC represents a compelling route for solar-to-chemical energy conversion.

BiVO4 is particularly attractive for such applications due to its low cost, environmental safety, and photochemical stability, making it well-suited for large-scale implementations in environmental remediation and hydrogen generation.

In PEC systems, the application of an external bias facilitates charge separation and suppresses electron–hole recombination, thereby improving overall photocatalytic efficiency. Further enhancements through doping, morphology control, and heterojunction engineering have continued to improve the performance of BiVO4-based electrodes. Current research trends and degradation efficiencies in PEC systems are critically evaluated28.

Despite the extensive knowledge surrounding BiVO4, recent reviews have primarily focused on water-splitting and photocatalytic applications. In contrast, this review provides a comprehensive analysis of the physicochemical principles governing PEC systems based on BiVO4, with particular emphasis on environmental remediation. We examine charge generation, separation, and transfer mechanisms in BiVO4 photoanodes and assess their impact on the degradation of various pollutants. Additionally, we explore synthesis strategies and surface modification techniques—including doping and structural optimization—highlighting their role in improving charge transfer, reducing recombination, and enhancing overall system performance. These insights underscore the potential of BiVO4 as a sustainable, multifunctional material for efficient solar-to-chemical energy conversion and environmental applications

Catalysis, electrocatalysis, photocatalysis, and photoelectrocatalysis

Catalysis, electrocatalysis (EC), photocatalysis (PC), and PEC are distinct yet interrelated processes that utilize catalysts or catalyst-like materials to facilitate chemical transformations under varying conditions. Catalysts work by lowering the activation energy of a reaction, thereby increasing the reaction rate without altering the thermodynamic equilibrium. These reactions typically require external inputs such as elevated temperature or pressure to initiate or sustain reaction kinetics (Fig. 2a). EC involves an electrode—typically a metal—that enhances electrochemical reactions at its surface, driven by an external electrical potential or current (Fig. 2b). PC involves the absorption of photons by the photocatalyst, which generates electron-hole pairs. These pairs then participate in redox reactions to degrade pollutants or produce useful chemicals (Fig. 2c). Lastly, PEC combines light irradiation and an applied electrical potential to enhance reaction rates; the catalyst functions under both conditions, promoting redox reactions and reducing recombination losses, making it particularly effective for processes like hydrogen production and environmental remediation (Fig. 2d). BiVO4 can function as both a photocatalyst and photoelectrocatalyst. Therefore, while this discussion covers PC, it primarily focuses on PEC.

Catalysis

Catalysis (Fig. 2a) is a phenomenon where traces of a foreign material (the catalyst) increase the rate of chemical reactions29. The catalytic process typically involves the following elementary steps: (i) Diffusion of the substrate to the catalyst surface; (ii) Adsorption of the substrates onto the active sites of the catalyst; (iii) Chemical reaction forming products on the catalyst surface; (iv) Desorption of the products from the active sites; (v) Catalyst regeneration for new chemical reactions (though catalysts are not indefinitely reusable)29,30.

At the molecular level, a chemical reaction occurs when reactants collide with sufficient energy to overcome the activation energy barrier, leading to bond-breaking and the formation of new, more stable bonds, molecules, or atoms (i.e., products). A catalyst facilitates this process by spontaneously adsorbing one of the reactants, which causes the molecules to lose rotational and translational degrees of freedom. This process helps break the bonds of the adsorbed reactant, guiding the reaction down a more energetically favorable pathway. As shown in Fig. 3a, the free energy of the catalyzed (blue line) and uncatalyzed (green line) reactions is the same, meaning the catalyst does not affect the equilibrium constant, which depends only on the reactants and products. In other words, the catalyst changes reaction kinetics by generating intermediates (IM–n, related to adsorption, reaction, and desorption processes) to bypass traditional transition state (TS) (Fig. 3) but does not alter the thermodynamics of the chemical reaction29,30,31.

a Typical reaction energy diagram of the uncatalyzed reactions (green line) and catalysis reaction (blue line), where TS is a transition state, IM-n are intermediates. Adapted from Kakaei et al.29 b Removal efficiency percentage of polystyrene microplastics by electrooxidation. Taken from Kiendrebeogo et al.39.

Electrocatalysis

EC is a heterogenous catalytic process involving electrochemical reactions on the electrode–electrolyte interface (Fig. 2b). In this process, the electrode serves as both an electron donor/acceptor and catalyst, hence it is termed “electrocatalyst”32,33. EC can also be defined as the introduction of catalytic materials on the electrode surface to increase the rate of electrochemical reactions while using a potential perturbation value equal to or less than that used without a catalyst; this generally results in a substantial increase in electron transfer efficiency34. This latter definition closely resembles that of heterogeneous catalysis but incorporates additional assistance by electric potential perturbations.

A helpful example used to explain EC is the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) in Reaction 135. As reactions with an outer-sphere mechanism are generally not considered electrocatalytic, we will focus on the typical HER pathway36. Thus, the formation of H2 occurs according to (i) the Volmer reaction, electrosorption with formation of •H (Reaction 2), followed by (ii) the Heyrosky reaction, electrochemical reaction between •H and H+ (Reaction 3) or (iii) the Tafel reaction (chemical reaction between two adjacent •H).

As in heterogenous catalysis, here, the final two steps involve product desorption and electrode reactivation. Reaction 1 does not occur spontaneously, as the electrode must donate an electron to the proton for the reaction to progress.

The interaction between the electrode and the reactant significantly influences the reaction rate. For instance, in the case of H2 production, the electrode material reduces the reaction kinetics; if Pt is replaced with Hg, the reaction rate decreases35,37. This relationship is illustrated in Table 1, where the exchange current jo represents the charge exchange rate at equilibrium per unit area. A larger jo values indicates more a favorable charge transfer and faster reaction, whereas a smaller value corresponds to a slower rate36.

Another crucial factor in EC is the overpotential. In electrochemical systems, increasing the overpotential generally increases the reaction rate; however, the work potential is based on the objective of the assay. For instance, in electrosynthesis in aqueous media, if the overpotential exceeds the potential of O2 or H2 production, the Faradaic efficiency (FE) may decrease or by-products could be produced.

The electrocatalytic process has gained significant attention in the field of wastewater decontamination. Its versatility has enabled the development of complex systems. A notable example is the anodic oxidation of polystyrene microplastics on a boron-doped diamond (BDD) electrode, which exemplifies the potential of electrocatalysis in addressing persistent pollutants. In this process, both the electrolyte and water undergo electrooxidation via the abstraction of one electron, initiating the formation of reactive species capable of attacking and breaking down the polymer matrix. This process can generate HOROS such as hydroxyl radical (•OH) and sulfate radical (\({\mathrm{SO}}_{4}^{\bullet -}\)) by mean reactions of single electron transfer promoted by the external supply. In the studies of Lu et al.38 and Kiendrebeogo et al.39 show that these oxidized species have the most important contribution in the degradation38,39. Since these radicals are what degrades the polystyrene microplastics, it is referred to as indirect oxidation. Additionally, by changing the material nature, the degradation present and important change, too. BDD achieved up to ~90% of removal efficiency while electrodes such as iridium oxide (IrO2) and mixed metal oxides (MMO) just achieved up to ~20% and ~10%, respectively39 (Fig. 3b). This significant contrast in the degradation percentages is because BDD is a pour catalyst for O2 evolution (the oxygen evolution reaction is slow), which makes it in a good catalyst to produce •OH40,41,42. It reveals how the electrocatalyst can form “exotic species” and how the material influences in their formation, as discussed in this section.

Photocatalysis

PC is a type of heterogenous catalytic process in which a chemical reaction is accelerated in the presence of a photocatalyst under light irradiation, typically described in terms of photon energy (hν), Fig. 2c43. Depending on the photocatalyst’s physical state, PC can be classified as homogenous or heterogenous. In heterogenous PC, the photoactive material is usually in the solid state and can take various forms44. The PC process involves the following four steps: (i) Irradiation of the photocatalyst, using either sunlight or artificial light sources (e.g., LEDs or traditional lamps) whose energy exceeds that of the material’s bandgap energy (hν > Ebg); (ii) Excitation of electrons (e−) from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), generating holes (h+) in the VB; these charge carriers are referred to as “photogenerated \({{\rm{e}}}_{{\rm{CB}}}^{-}\)/\({{\rm{h}}}_{{\rm{VB}}}^{+}\) pairs”45; (iii) Adsorption of the substrate onto the photoactivated catalyst surface; (iv) Redox reaction of the substrate46. The efficiency of the process primarily depends on the photocatalyst material, which must satisfy the following criteria47: (i) an appropriate energy difference between the CB minimum (ECB) and VB maximum (EVB); (ii) suitable band-edge positions of ECB and EVB, that provide the required redox potentials to drive the desired reduction/oxidation reactions; and (iii) favorable dynamics of the photogenerated \({{\rm{e}}}_{{\rm{CB}}}^{-}\)/\({{\rm{h}}}_{{\rm{VB}}}^{+}\) pairs, including low recombination rates, sufficient diffusion lengths, high mobility, and efficient charge transfer.

In PC, charge transfer reactions occur simultaneously, with reduction taking place in the CB and oxidation in the VB. However, one of these half-reactions typically limits the overall process, which can be kinetically described as: d[h+]/dt = d[e-]/dt. It is therefore essential to distinguish PC processes based on their energy balance. When the oxidation of organic compounds is coupled with hydrogen (H2) generation, the reaction is classified as photosynthetic, owing to its positive Gibbs free energy change under dark conditions. In contrast, if charge neutrality is maintained via O2 reduction, the process is considered conventional photocatalysis. Nevertheless, photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems provide the most direct and accurate means of characterizing and quantifying these processes48. PC is currently regarded as one of the most promising approaches for wastewater treatment, as it facilitates the generation of •OH, superoxide radicals (\({{\rm{O}}}_{2}^{\bullet -}\)), and photogenerated holes (\({h}_{{VB}}^{+}\)) under light irradiation49. These HOROS act as strong oxidizing agents that attack a wide range of organic compounds, initiating sequential reactions that lead to extensive oxidation and, in some cases, complete mineralization. Consequently, PC is classified as an AOP46.

For instance, in the photocatalytic degradation of Basic Red 46 using an Fe-doped BiVO4/SnO2 photocatalyst, the formation of excitons in the composite triggers the formation of HOROS. Initially, the system undergoes a 30-minute adsorption–desorption equilibrium stage in the dark, during which the pollutant concentration in the bulk solution slightly decreases. Upon light irradiation, oxygen molecules in the medium react with \({{\rm{e}}}_{{\rm{CB}}}^{-}\) in CB from the SnO2 component to form \({{\rm{O}}}_{2}^{\bullet -}\), while water molecules are oxidized by \({{\rm{h}}}_{{\rm{VB}}}^{+}\) in VB of the Fe-doped BiVO4 to yield •OH. According to Abrishami-Rad et al.50, both radical species significantly contribute to the degradation of Red 46 (Fig. 4a).

Photoelectrocatalysis

PEC is a heterogenous PC process assisted by the application of a relatively small external potential or current, Fig. 2d12,51. In a typical PEC system, the working electrode is a photoelectrode consisting of a semiconductor-based photocatalyst supported on a conductive substrate (electrode). Upon illumination with light of energy greater than the photocatalyst’s bandgap, the photoelectrode becomes photoactivated, while the applied external potential facilitates charge separation and transport by minimizing recombination losses. The specific perturbation depends on the characteristics of the photoelectrode (n-type or p-type) and the desired reaction (photoelectrooxidation or photoelectroreduction). Instead of potential perturbation, external current perturbations can also be used, either cathodic (ic) or anodic (ia)45. PEC is considered an AOP when the photoelectrogenerated holes in the VB have an oxidation potential high enough to produce •OH from water oxidation. •OH is one of the strongest oxidants in nature, chemically green, and non-selective (E°•OH/H2O = 2.74 V vs. SHE), making it suitable for degrading (oxidizing) persistent organic compounds, either to achieve complete mineralization or to generate products useful for circular economy purposes12. Photoelectrochemical oxidation occurs through both •OH and photoelectrogenerated \({h}_{{VB}}^{+}\). For instance, the proposed PEC mechanism of glycerol (substrate) on BiVO4 is outlined in Fig. 4b: (i) Light generates \({e}_{{CB}}^{-}\)/\({h}_{{VB}}^{+}\) pairs; (ii) The substrate adsorbs onto the surface; (iii) Holes react with the substrate; (iv) The generated oxidizing agents react with the organic compound (degradation pathway) or with itself (recombination); (v) The molecule undergoes dehydration; (vi) The derivatized substrate desorbs from the surface.

Factors affecting the photoelectrocatalytic process based on BiVO₄

Effect of light in PEC systems

For BiVO4, which has a bandgap energy (Ebg) of 2.4 eV, photons with a wavelength of at least 517 nm (within the visible spectrum) are required to initiate excitation, according to the relation E = hc/λ. Photons with energy greater than Ebg can effectively induce charge separation through light absorption52. In a PEC system, Tateno et al.53 investigated the oxidation of 1-phenyl ethyl alcohol under illumination with various wavelengths. As shown in Fig. 5b, lower-energy (longer-wavelength) light required approximately 2.5 times more applied potential to achieve comparable FE. This behavior correlates with the light-harvesting efficiency of the BiVO4 photoanode (Fig. 5a), which exhibits a maximum response around 460 nm. At longer wavelengths, the efficiency declines sharply due to reduced photon absorption.

a Light-harvesting efficiency spectra of BiVO4/WO3 composite, BiVO4, and WO3 photoanodes. b Effect of wavelength on the photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of 1-phenyl ethyl alcohol. Adapted from Tateno et al.53.

The reduction in FE under low-energy illumination can be rationalized by fundamental principles of semiconductor physics. When a light beam with energy close to the semiconductor’s Ebg irradiates its surface, an electron in the VB is excited to the CB (Fig. 6a). However, such an electron may recombine with the hole via radiative recombination, emitting a photon with energy close to Ebg (Fig. 6c). On the other hand, when the light energy is significantly greater than Ebg, the excited electron transitions to a higher energy level, typically a non-bonding molecular orbital in the CB. In this case, instead of remaining at the CB edge, the electron undergoes a process called “relaxation,” descending to the CB edge while releasing energy as heat (Fig. 6b)54. Therefore, PEC efficiency depends on the overlap between the charge carrier energy levels and the allowed states in the molecular orbitals of the reactive species at the interface. In the PEC process, maximizing the number of available charge carriers is essential, as they are driven toward the external circuit with the aid of an external potential.

Light intensity is another crucial parameter that directly influences the efficiency of PEC systems. Zainal et al.55 examined the PEC degradation of methyl orange using TiO2 under illumination from a 300 W tungsten lamp. By adjusting the lamp’s intensity to 100%, 75%, 50%, 25%, and 0%, they monitored dye degradation over 2 hours. The results demonstrated that the degradation rate increased with light intensity, the greater the photon flux incident on the semiconductor surface, the higher the generation rate of photogenerated \({e}_{{CB}}^{-}\)/\({h}_{{VB}}^{+}\) pairs, thereby promoting the formation of HOROS and accelerating dye degradation. The relationship between degradation efficiency and light intensity exhibited an exponential trend, highlighting the importance of considering this parameter in the optimization of PEC processes55,56. Notably, any factor that affects light intensity or wavelength—such as solution turbidity or excessive absorbance—can impair charge carrier generation and thus reduce PEC performance. Optimizing the direction of light irradiation is a practical strategy to mitigate these losses. For instance, semi-transparent BiVO4-modified electrodes have shown improved performance when illuminated from the back side, as this configuration enhances charge carrier generation at the electrode–semiconductor interface, facilitating their transfer into the external circuit57. Moreover, placing the light source inside the reactor ensures more direct illumination of the photoelectrode, minimizing losses due to scattering and absorption by the solution45. Thus, PEC cell design must meet two key requirements: (i) maximizing photoelectrode light absorption and (ii) enhancing mass transfer within the reactor system58.

Semiconductor properties and photoelectrode behavior

Semiconductors are classified into n-type and p-type based on their majority charge carriers. In n-type semiconductors, the Fermi level (EF) lies closer to the CB, making holes generation in the VB more favorable. Conversely, p-type semiconductors have EF near the VB, thereby facilitating electron production. In simpler terms, n-type semiconductors have electrons as majority carriers and holes as minority carriers, while p-type semiconductors exhibit the opposite behavior59. Based on this classification, PEC electrodes can be categorized as photoanodes (n-type semiconductors), which facilitate oxidative processes under appropriate illumination, and photocathodes (p-type semiconductors), which promote reductive processes.

The photoelectrode type plays a crucial role in the PEC process and its applications. This distinction is evident when comparing the photocurrent response of p-type and n-type BiVO4 under various applied potentials. In one study, tetragonal zircon phase-type BiVO4 -tz-BiVO4 (commonly referred to as p-BiVO4 due to its p-type characteristics) was synthetized via a hydrothermal method and deposited onto a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) electrode. Subsequent annealing at different temperatures to obtain monoclinic scheelite-type BiVO4−ms-BiVO4 (n-BiVO4) (Fig. 7a). As confirmed in the Mott–Schottky plots (Fig. 7c); a clear shift in slope at 450 °C indicates a transition from p-type to n-type conductivity. This transition substantially impacts the lineal sweep voltammetry (LSV) test under chopped light illumination (Fig. 7b). Specifically, p-BiVO4 exhibited enhanced photoactivity at cathodic potentials, consistent with its reductive behavior, while n-BiVO4 showed superior performance under anodic conditions, supporting oxidative reactions60.

a X-ray diffraction patterns, b LSV curves under chopped light, and c Mott–Schottky plots. Adapted from Wang et al.60.

Semiconductor morphology a critical role in determining PEC performance. For instance, a porous BiVO4/FTO photoanode exhibited an improvement of over 99% in FE and 87.4% in selectivity compared to a conventional BiVO4/FTO photoanode. These enhancements are attributed to reduced charge recombination, improved charge separation, extended light absorption, and a larger effective surface area61,62,63. Unlike conventional PC, where the semiconductor is typically dispersed in suspension, PEC offers greater operational efficiency by suppressing charge recombination, enhancing the synergy between electrochemical and photochemical pathways, and eliminating the need for photocatalyst recovery thus enabling the reuse of durable photoelectrodes. In PEC systems, however, it is important to consider both the exposed facet of the semiconductor—commonly addressed in PC—and the orientation of the crystal on the electrode surface, which is uniquely relevant to PEC. With respect to facet exposure, Zhang et al. investigated BiVO4 photoanodes with dominant (010), (010)/(110), and (110) facets. Their findings demonstrated that photoanodes dominated by the (010) facet exhibited superior photoelectrochemical performance, attributed to the deeper valence band energy associated with this crystallographic orientation64,65.

The impact of crystal orientation was further explored by Lu et al.66, who compared two fabrication strategies: a seed-layer method to control facet exposure and conventional electrodeposition to generate a nanoporous surface. A randomly oriented surface, produced via hydrothermal synthesis, showed a low photocurrent density of 0.3 mA cm−2, while exposure of the high-exposed (040) facet led to a substantial increase in photocurrent—reaching 2.2 mA cm−2—surpassing even the classical electrodeposition approach (1.3 mA cm−2). These findings are consistent with the work of Zhang et al.67, who prepared BiVO4 powders with preferential (010) facet growth and demonstrated that, despite well-defined crystalline facets, random orientation on the electrode surface significantly limited PEC activity. Lastly, the adsorption of reagents and products on the photoelectrode surface is a crucial parameter influencing PEC performance. For example, when a TiO2 electrode was used in the synthesis of azobenzene, the FE decreased to 62.0% compared to that observed with a BiVO4 electrode63. Such limitations highlight the challenges of continuous PEC operation, as many pollutants and organic substances remain adsorbed on the photoelectrode, hindering its continuous use58. Moreover, the surface composition of the semiconductor also plays a role. In water-splitting reactions, variations in the interfacial concentration of Bi or V have been shown to affect band edge positioning and charge separation efficiency68.

Effect of applied potential in PEC systems

The high energy consumption in EC and the high charge carrier recombination in PC make PEC a promising alternative for water decontamination69. Under constant light intensity, the generation rate of charge carriers in a semiconductor remains constant until perturbed by an external factor. When an external potential or current is applied, electrons in the CB are efficiently extracted into to the external circuit, thereby suppressing charge carriers’ recombination. Additionally, an electron donor compound (i.e., a reducing agent) must be available at the semiconductor–electrolyte interface to fill the holes created by photoexcitation. As the applied potential increases, the photocurrent correspondingly rises69,70. However, if the reducing agent does not fill the holes fast enough, or the surface becomes saturated with oxidized products, the photocurrent will be limited by the charge carrier recombination56,71. Despite the recombination limitations that may exist in PEC, its synergistic nature allows it to achieve high decontamination efficiencies even under low overpotential conditions.

Applying an external potential not only drives charge separation, but also directly influences the semiconductor itself. When a photoelectrode is immersed in an electrolyte solution, electrostatic interactions between the semiconductor and the solution cause a shift of the EF of the semiconductor. This displacement induces band bending and establishes a quasi-Fermi level (EF,equil.), which reaches equilibrium with the redox potential of the solution (EF,redox). This phenomenon, knows as “band bending,” originates at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface and extends into the bulk of the semiconductor, forming a space charge layer (SCL) or space charge region (Fig. 8a). The SCL plays a crucial role in PEC by promoting charge separation and suppressing charge carrier recombination45. The SCL thickness depends on the potential and varies in relation to the flat band potential (Efb), Efb defining the potential at which no excess charge exists at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface, the semiconductor/electrolyte interface is in electrostatic equilibrium72. When the applied potential exceeds Efb, the SCL widens, further shifting the semiconductor’s EF and enhancing charge separation. Conversely, if the applied potential (E) is equal to the Efb, the SCL approaches zero thickness, and EF aligns with the quasi-Fermi level. With knowledge of a semiconductor’s bandgap, it become possible to estimate the absolute position of the conduction and valence bands47,73. Overall, the applied potential modulates the delicate balance between carrier recombination and charge transfer.

a Formation of the space charge layer (SCL) at the semiconductor−solution interface. b Charge transfer rate constant (red) and recombination rate constant (black) for unmodified (open symbols) and CoPi-modified BiVO4 (closed symbols). The error bars represent the variability in measurements for different samples at selected potentials. In total, three bare BiVO4 electrodes and two BiVO4/CoPi electrodes were analyzed. Figure and description adapted from Zachäus et al.196.

Band bending not only enhances charge separation but also facilitates electron extraction and diminishes recombination losses. Intensity-modulated photocurrent spectroscopy (IMPS) studies have shown that BiVO4 photocurrent response is predominantly limited by surface recombination rather than surface catalysis22. By quantifying the charge recombination and transfer rate constants—both determined by IMPS—for bare BiVO4 and BiVO4 photoanodes modified with cobalt phosphate (CoPi), it has been shown that CoPi suppresses surface recombination by a factor of 10 to 20 (Fig. 8b). Surprisingly, the charge transfer rate constant is minimally affected, despite the well-established electrocatalytic properties of CoPi. This reduction in recombination leads to an overall increase in charge transfer efficiency, which is consistent with the observed improvement in photocurrent. This topic will be further discussed in a later section. In summary, Fig. 8 provides evidence—based on kinetic constants—that the applied potential reduces recombination much more significantly than the enhancement achieved through modification. This finding underscores the complex interdependence between charge transfer dynamics and recombination processes in PEC systems.

Adapted from Tayyebi et al.57.

Effect of temperature on PEC performance

As discussed in previous sections, temperature change occurs naturally through relaxation or recombination. The quasi-Fermi levels of holes (\({E}_{F,{h}^{+}}^{q}\)) and electrons (\({E}_{F,{e}^{-}}^{q}\)) are affected by temperature variations and described by Eqs. (5) and (6):

where kB, is the Boltzmann constant (1.380649×10−23 J/K); \({N}_{{eff},V/C}\) represents the effective density of states in the CB or VB; ne and nh are the electron and hole concentrations, respectively; and T is temperature. These parameters determine the potential of quasi-Fermi levels in a pristine semiconductor74,75.

In the case of TiO2, energy band positions shift with temperature. Specifically, the VB moves toward more positive potentials (vs. vacuum), while the CB shifts toward more negative potentials (vs. vacuum). Consequently, the Ebg of the semiconductor narrows as the temperature increases76. Generally, the performance of PEC systems improves with increasing temperature. Chanyu et al. investigated this effect using BiVO4 thin-film photoanodes as a model system77. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy revealed that the improvement is primarily due to improved charge transport efficiency within the bulk of the material, rather than increased interfacial charge injection. Polarization curves revealed for both water and sulfite oxidation showed a shift toward less positive onset potentials, attributed to enhanced charge separation and reduced recombination77. However, the enhancement in PEC performance by temperature is not unlimited. Biswas et al. reported that the photocurrent in TiO2 reaches a maximum at 45 °C in NaOH and KOH solutions, attributing the subsequent decline to pH changes at higher temperatures76. Similarly, the α-SnWO4 photoanode exhibited its maximum photocurrent at 50 °C in a KOH/H3BO3 buffer (pH = 9) containing 0.2 M Na2SO3. Beyond this temperature, the photocurrent declined due to photoanode degradation78. On the other hand, Liu et al.79 found that for CuWO4, the photocurrent decrease at elevated temperatures was primarily due to increased recombination rates. As the temperature rises, carrier mobility increases, which extends the minority carrier diffusion length, allowing carriers to reach the electrode faster and increasing the photocurrent. However, this increased carrier mobility also reduces carrier lifetime compared to that at room temperature, which can affect the photocurrent at higher temperatures if mobility does not counteract recombination59,79. Surprisingly, BiVO4-based PEC systems exhibit an irreversible enhancement in photocurrent following high-temperature treatment, even upon returning to room temperature. At high temperatures, the kinetics of interfacial reactions also increase, leading to a drop in localized surface pH due to oxidation reactions (e.g., citrate or sulfite oxidation), which produce H+ and contribute to BiVO4 photo-corrosion. This results in the reprecipitation of BiVO4 as an amorphous surface layer. Since amorphous BiVO4 possesses a more energetic VB and a comparable Ebg to its crystalline counterpart, electron extraction is facilitated, thereby improving the photocurrent response77.

In summary, temperature influences PEC dynamics in both the SCL and the semiconductor-electrolyte interface, primarily influencing reaction kinetics, charge transfer rates, and species adsorption. These effects can significantly impact conversion efficiency and recombination dynamics. Additionally, temperature-induced changes in the interactions among water, ionic species, and the semiconductor surface may alter electrode composition and increase susceptibility to photocorrosion.

Effect of pH on PEC performance

Beyond its well-known influence on electrochemical processes, pH also plays a crucial role in photochemical reactions, influencing the species produced and the reaction pathways in PEC systems. In an alkaline medium, oxygen evolution on a BiVO4 photoanode proceeds via the oxidation of OH− by h+, producing H2O and O2. In contrast, under acidic conditions, the O2 evolution pathway involves the direct oxidation of H2O by h+ 57.

The influence of pH on photocurrent response has been studied using BiVO4/FTO as a model photoelectrode57. Tayyebi et al.57 systematically examined photocurrent generation at acidic (pH 2.5), neutral (pH 6.5), and alkaline (pH 9.5) conditions. LSV assays revealed a distinct trend across the potential range. At low applied potentials (up to ~0.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl), the photocurrent was highest in acidic media up to ~0.3 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), consistent with previously reported behavior for NiO/ZrO2 electrodes80. From 0.3 V to 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), the highest photocurrent occurred in alkaline media. However, at higher potentials (1.4–1.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl), the trend reversed, with acidic media again yielding the highest photocurrent. This behavior is attributed to potential-dependent modifications in the Helmholtz layer and shifts in the quasi-Fermi level, both of which are influenced by the differential adsorption of H+ and OH⁻ species at the semiconductor–electrolyte interface, as described in Eq. (7)57:

These interface variations induce band bending within the semiconductor, which either facilitates or impedes charge separation. For instance, in alkaline media, the BiVO4 photoanode exhibits an upward shift in energy band positions, resulting in increased band bending that enhances charge separation efficiency (Fig. 9)57.

In the case of TiO2, pH plays a pivotal role in the PEC degradation of organic compounds by modulating surface charge and molecular interactions. Under highly acidic media, protons (H3O+) adsorb onto the TiO2 surface, rendering it positively charged and thereby repelling cationic species. On the other hand, in alkaline media, the adsorption of OH⁻ results in a negatively charged surface that enhances the attraction of cationic species. A key parameter governing this behavior is the point of zero charge (pHpzc)70. For BiVO4, which has a pHpzc ~3.4, the surface becomes positively charged below this value due to H3O+ adsorption, leading to electrostatic repulsion of cationic species. Conversely, above this pH, the surface repels anionic species81,82. However, in PEC systems, the surface charge of the semiconductor is also influenced by the applied potential. For n-type semiconductors, anodic polarization induces a positive surface charge, which alters electrostatic interactions and, in turn, influences the degradation efficiency of organic molecules.

In addition to its effect on surface charge, pH can significantly alter the chemical structure and speciation of target compounds in solution. For instance, the PC degradation of p-nitrophenol (PNP, pKa ~ 7.1) on TiO2 (pHpzc ~ 6.2) is strongly pH-dependent, altering its adsorption behavior83. At pH 5, the TiO2 has a positive charge, while at pH 8, it becomes negatively charged, thus modifying the adsorption behavior of PNP. Various interaction mechanisms between PNP and TiO2 surface have been proposed84, including hydrogen bonding with Ti–H2O complexes, which become stronger at higher pH and enhancing degradation efficiency83. The most effective degradation occurs at pH > 8, making alkaline conditions particularly favorable for environmental water treatment applications.

Similar effects are expected for BiVO4-based systems, where pH is anticipated to influence the adsorption and degradation of organic pollutants through surface charge modulation. As the evidence suggests, the profound and varied effects of pH exerts multifaceted effects on PEC processes, underscoring the complexity of understanding and optimizing BiVO4 photoelectrochemical performance. These intricacies will be explored in greater detail in the following subsection.

Effect of pH on PEC performance and stability of BiVO4

The pH modulates the flat-band potential and surface proton activity, thus altering the interfacial energetics and kinetics of water oxidation on BiVO4. As the pH increases, the valence band edge shifts ~−59 mV/pH, affecting the thermodynamic driving force for hole-mediated oxidation in the VB. However, this also increases the local concentration of OH−, which can contribute a greater quantity of •OH after the oxidation of water, but if there is saturation, it can also favor the chemical recombination of radicals. The oxygen evolution reaction (OER) proceeds via multi-step proton-coupled electron transfers (PCET), typically involving adsorbed intermediates such as S–OH*, S–O*, and S–OOH*, whose formation barriers are pH-dependent85. Here, S refers to the surface and * denotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) intermediates formed in situ.

The overall half-reaction remains:

but the reaction kinetics and surface coverage of intermediates vary with pH, influencing the steady-state photocurrent and product selectivity.

The long-term chemical stability of BiVO4 under PEC operation is also strongly pH dependent. In acidic media, BiVO4 undergoes pronounced dissolution, especially via vanadium leaching, due to the higher solubility of vanadate species and the increased chemical potential for metal release. A representative dissolution pathway is:

At near-neutral pH, dissolution is kinetically hindered, and surface passivation can occur through the formation of Bi2O3-like layers, which may impede hole transfer. In alkaline media, stability improves due to the lower solubility of Bi3+ and VO43− species, although the accumulation of OH− at the interface can still foster recombination. Additionally, the surface formation of BiO(OH) may either protect or resist charge transfer depending on its structural order and coverage. These competing mechanisms highlight the intricate balance between performance and degradation, where pH simultaneously modulates charge carrier dynamics, photocorrosion rates, and interfacial reactivity. For a more detailed description of the multiple dissolution and transformation reactions of BiVO4, as well as mechanistic insights and analysis of the Pourbaix diagram, we recommend the reader to consult the comprehensive studies published in the literature86,87.

Theoretical work by Ambrosio et al. offers atomic-level insight into these pH effects by developing a methodology that combines ab initio electronic structure calculations, molecular dynamics, and thermodynamic integration88. This approach enables the determination of the pKa values of specific surface adsorption sites and the calculation of the pHpzc, as well as the dominant water adsorption mode (molecular vs. dissociative) on (010)BiVO4. The resulting speciation diagram indicates that from pH 2 to 8, the interface is predominantly covered by molecularly adsorbed water, while HO− becomes the main adsorbed species above pH 8.2. Proton adsorption is negligible except under strongly acidic conditions. These findings support the view that interfacial site occupancy, dictated by pH, strongly influences hole transfer kinetics and surface recombination, and thus governs the observed PEC response.

Experimental studies confirm that BiVO4 exhibits slow, uniform dissolution under operating conditions, mainly due to the buildup of photogenerated holes at the surface and the lack of spontaneous passivation via Bi oxides87. Complementary work by Tao et al. supports a degradation mechanism involving preferential V leaching, with surface enrichment of Bi2O3 or Bi4O7 acting as passivating layers that reduce photocorrosion but also impede charge transport86. Furthermore, Singh et al. introduced a first-principles thermodynamic metric (Gibbs free energy difference with respect to stable Pourbaix domains, ΔGpbx) to quantify the metastability of BiVO4 (~0.59 eV/atom)89. Although BiVO4 falls in a metastable regime, its operational stability at near-neutral pH is attributed to kinetic barriers and dynamic surface reconstruction, underscoring the limitations of purely thermodynamic descriptors.

Beyond its well-documented influence on semiconductor band edge positions and surface charge, pH profoundly dictates the speciation of organic pollutants and affects their interfacial dynamics during PEC water treatment using BiVO4 photoanodes. Many organic contaminants exist as acid-base pairs, and their protonation state, defined by solution pH, critically impacts their adsorption characteristics, oxidation mechanisms, and ultimately, electron transfer kinetics at the semiconductor-electrolyte interface90,91,92. While the BiVO4 surface typically carries a negative charge above its isoelectric point90, under PEC operation (where the photoanode is illuminated and polarized) a spatial charge separation occurs. This generates hole accumulation at the surface, resulting in positive local charge regions that can attract anionic species, thereby facilitating interfacial electron transfer. It’s worth remembering that, given the proven generation of •OH from water oxidation on BiVO4, the indirect oxidation of organic compounds by these radicals is the typically expected mechanism.

The interaction behavior of selected organic compounds with BiVO4 is expected to conform to trends predicted and experimentally observed across diverse PEC systems. For instance, deprotonated species such as carboxylates and phenolates tend to interact more strongly with the BiVO4 surface under near-neutral to alkaline conditions, often resulting in enhanced PEC activity. Consider the degradation of carboxylic acids (e.g., acetic acid, benzoic acid) and phenolic compounds (e.g., phenol, bisphenol A): at low pH (acidic conditions, below their respective pKa values), these compounds exist predominantly in their neutral, protonated forms (R-COOH and Ar-OH), which exhibit limited adsorption due to weaker electrostatic interactions or even repulsion. This limits direct hole transfer from the valence band and ultimately slows down the degradation kinetics. In contrast, under alkaline conditions (pH above the pKa), these species deprotonate into their anionic forms, carboxylates (R-COO−) and phenoxides (Ar-O−), which are electrostatically attracted to the positively polarized BiVO4 surface under illumination and bias. This facilitates interfacial adsorption, improves charge transfer efficiency, and promotes oxidative degradation. Additionally, the increased electron density on the oxygen atoms in these anions enhances their susceptibility to oxidation by valence band holes or surface-generated hydroxyl radicals, further accelerating PEC reactivity. Oppositely, organic compounds containing amine groups (e.g., aniline) exhibit an inverse pH dependence. At low pH, amines are protonated to form cationic ammonium species (R-NH3+), which are repelled by the positively charged photoanode, hindering adsorption and reactivity. As the pH increases, these molecules deprotonate to their neutral forms (R-NH2), which, while not strongly attracted electrostatically, remain susceptible to oxidation by photogenerated h+ or •OH.

These ideas underscore the intricate interplay between pH, surface charge, and PEC-induced polarization in modulating pollutant adsorption and oxidation kinetics. Deviations from these behaviors may result from non-ideal interfacial interactions or surface modifications associated with solid-state transformations. In this context, in situ interfacial characterization using spectroelectrochemical techniques is strongly encouraged as a key tool for mechanistic elucidation.

Future advancements in PEC water treatment require integrated approaches that combine speciation modeling of representative pollutants with experimental photocurrent and degradation measurements. Such efforts will clarify the pH-dependent interfacial behavior of organic contaminants on BiVO4, enabling optimized operational conditions that maximize degradation efficiency and photoanode stability. Understanding the precise mechanistic pathways, whether direct hole oxidation, indirect radical attack, or mediated electron transfer, as functions of pH and organic speciation are crucial for designing more effective and selective PEC systems.

As highlighted in this section, careful control and documentation of factors affecting the PEC process are essential for future reproducibility. A summary of the catalytic processes is provided in Table 2.

Properties of BiVO4 and comparison with other metal vanadates

Metal vanadates are a big family conformed for structures such as MVO4, MV2O4, MV2O6, MV3O8, M2V2O7, and M3V2O8 (where M is an alkaline earth/transition/rare earth/other metal). Promising photocatalyst based on TiVO493, SmVO494, Ag3VO495 and V2O596 have to be studied in contaminant elimination and hydrogen production; nevertheless, the photoelectroactivity of these materials is poor. For instance, photoanodes based on Ag3VO4 showed the maxima photocurrent of 19 μA cm−2 at 1.23 V (vs. RHE) while BiVO4-photoanodes can achieve up to 130 μA cm−2 even at less potentials (0.20 V vs. Ag/AgCl or around 0.40 V vs. NHE)95,97. Also, not all vanadate presents photoactivity to make photoelectrodes. For instance, the Ni2V2O7 has a band gap of 2.17 eV and a band position to promote oxidation reaction; however, it does not happen. This vanadate has to undergo a hydrogen treatment to have oxygen vacancies (NiV3O8) to present a little of photocurrent98. Although several metal vanadates shown roughly the same band positions as BiVO4 (Fig. 10), photoelectrochemical application has not studied deep.

Conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) of several metal vanadates used in photocatalysis such as Ni3(VO4)2282, FeVO4283, V2O596, Ca2V2O7284, quantum dots (QD)-Ni3(VO4)2285, GdVO4286, CaV2O6284, SmVO494, TiVO493, Ag3VO495, BiVO497, NiV3O898, Ni2V2O798, InVO4287, LaVO4288, Zn3(VO4)2289, YVO4290, and Mg3V2O8291.

Crystalline structure and optical properties

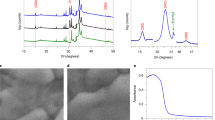

BiVO4 naturally occurs as mineral pucherite; however, when synthesized in the laboratory, it can adopt different crystal structures. As shown in Fig. 11a–c, four main crystal forms have been observed: orthorhombic (o-BiVO4, pucherite), monoclinic scheelite (ms-BiVO4, clinobisvanite), tetragonal zircon-type (tz-BiVO4, dreyerite), and tetragonal scheelite (ts-BiVO4, clinobisvanite), which features modifications in atomic positions compared to ms-BiVO449,99. Clinobisvanite can exist in either of the two scheelite structures—tetragonal or monoclinic—with the key difference being a greater distortion in the local environments of V and Bi ions in the monoclinic structure12,100. Although more than eight crystalline phases of BiVO4 have been reported, the monoclinic phase exhibits the best PC performance due to its bandgap energy of approximately 2.4 eV. Consequently, ms-BiVO4 is commonly used to produce photoanodes97,101. More recently, tz-BiVO4 has been employed in photoanode fabrication, and a combination of ms-BiVO4 and tz-BiVO4 has been explored for water splitting without the need for an external bias102,103.

a o-BiVO4, b tz-BiVO4, and c ms-BiVO4. Each crystalline form was obtained and adapted from the Crystallography Open Database. d Variation in the band positions of ms-BiVO4 facets. Adapted from Yu et al.106.

The monoclinic structure consists of vanadium ions coordinated by four oxygen atoms and bismuth ions coordinated by eight oxygen atoms from eight different VO4 units, forming layers25. In the tetragonal structure of BiVO4, the V–O bond lengths are equal at 1.72 Å, while the Bi–O bond lengths are 2.453 Å and 2.499 Å. Due to significantly distortion, the ms-BiVO4 structure loses its tetragonal symmetry, leading to changes in its bonds lengths: V–O (1.77 Å and 1.69 Å) and Bi–O (2.354 Å, 2.372 Å, 2.516 Å, and 2.628 Å)100. These distortions in the monoclinic structure enhance charge mobility due to the hybridization and overlap of Bi3+ (6 s2) orbitals with O2− (2p6) orbitals at the top of the VB12,104.

Density functional theory studies have shown that the VB is primarily composed of non-bonding O 2pπ states, with minor contributions from Bi 6s orbital, while the CB consists of V 3 d states104. The band positions of monoclinic BiVO4 (m-BiVO4) are approximately 0.32 eV for the CB and 2.47 eV for the VB97. Although the minimum bandgap, defined by the VB maximum and CB minimum, is an indirect bandgap of 2.17 eV, some studies classify BiVO4 as a direct bandgap semiconductor because it exhibits larger direct band gaps that are closer to experimental values105.

In recent years, the engineering of materials has made efforts to grow anisotropic materials in one direction or materials of one highly exposed facet. The bismuth vanadate is one of these anisotropic materials. The facets most studied of this material are {010} and {110}, which present slight differences. The (110) facet presents a CB energetically higher than the CB of the (010) facet, and vice versa, the VB of the (110) facet is energetically lower than the VB of the (010) facet (Fig. 11d). This variation in energy produces a movement of carriers resulting in an accumulation of holes and electrons in the (110) facet and (010) facet, respectively106,107,108. Strategies used to synthesize photoanodes with a preferred facet are explained in the Fabrication of BiVO4 Photoanodes section.

Stability of BiVO4 in photoelectrochemical systems

Despite its notable advantages, BiVO4 has several limitations, including susceptibility to photocorrosion, low electrical conductivity, and a sluggish charge transfer kinetics86,109. Under PEC processes in aqueous media, a passivation layer—primarily composed of bismuth oxides—tends to form on the electrode surface, which progressively reduces the photocurrent density. Notably, several studies have demonstrated that the use of saturated solutions of V5+ ions can substantially improve the operational stability of the BiVO4 photoanode86. Photocorrosion of BiVO4 becomes particularly pronounced in acidic environments. For instance, in H2SO4, a BiVO4/WO3/FTO photoanode can lose up to 74% of its photoactivity after only 120 minutes of PEC operation110. This phenomenon is likely due to the leaching of Bi3+ ions into the acidic medium, a process that can occur even in the absence of an external bias110. To further investigate this phenomenon, Li et al. studied the photocorrosion behavior of BiVO4 electrodes using both aqueous (0.1 M NaHCO3/H2O) and non-aqueous (0.1 M LiClO4/MeCN) media. Electrodes were first subjected to irradiation under applied potentials of 1.0 V or 1.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 24 hours, followed by 24 hours in the dark at open-circuit conditions, and finally exposed to another 24-hour PEC cycle under the same potentials. Photocorrosion was assessed through UV–Vis absorption spectra and photocurrent measurements. After approximately 96 hours of operation (four full cycles), electrodes in the aqueous medium exhibited a marked reduction in absorption between 400–600 nm (Fig. 12a) compared to those in acetonitrile (CH3CN), consistent with a greater degree of structural degradation. Similarly, photocurrent responses showed significantly diminished performance for the aqueous system (Fig. 12b). In contrast, the CH3CN-based medium effectively mitigated degradation, as evidenced by minimal losses in both absorption and photocurrent intensity71.

a UV–Vis spectra and b photocurrent vs. potential of a BiVO4 electrode before and after ~96 hours of photoelectrocatalysis. Adapted from Li et al.71.

Another critical factor influencing BiVO4 photocorrosion is the applied potential. Higher anodic potentials in acidic electrolytes tend to accelerate the corrosion process of the photoanode56. To overcome these challenges, recent efforts have focused on doping strategies aimed at enhancing the structural and photoelectrochemical stability of BiVO4, as discussed in the following sections.

Synthesis of powder BiVO4

The synthesis of BiVO4 powders commonly employs NH4VO3 as the VO43− source and Bi(NO3)3‧5H2O as the Bi3+ source. However, various other organic and inorganic precursors can be used (Table 3). Precise pH control is crucial for the successful formation ms-BiVO4, as hydroxyl and vanadate ions compete in aqueous solution. Under strongly alkaline conditions, especially during hydrothermal synthesis, undesired by-products such as tetragonal zircon-type (tz-BiVO4) and other vanadium-rich derivatives (e.g., Bi9VO16, Bi4V2O11, Bi12V2O23, Bi14,V5O33, and Bi2O3) can form, all of which exhibit lower PC activity compared to ms-BiVO4101. Despite these challenges, careful optimization of hydrothermal conditions—such as temperature, reaction time, and precursor concentration—can yield high-purity BiVO4 with minimal formation of secondary crystalline phases. Owing to its versatility and scalability, the solvo/hydrothermal route has emerged as the most prevalent method for producing high-quality BiVO4 powders for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical applications.

Annealing has become a key step to obtaining ms-BiVO4, the thermodynamically favored phase with superior photoactivity. Conversion to ms-BiVO4 is typically induced by thermal treatment at temperatures exceeding 397–497 °C, promoting an irreversible phase transformation from other less active crystalline forms111. This transition is facilitated by oxygen loss during annealing, which generates oxygen vacancies that stabilize the monoclinic structure and enhance photocatalytic performance. For instance, annealing under nitrogen atmosphere increases the density of oxygen vacancies compared to air treatment, thereby improving the photocurrent response of the resulting photoanode60. In a comparative study, Wang et al. demonstrated that BiVO4 annealed in nitrogen (BiVO4-N2) achieved a photocurrent density of 1.09 mA cm−2, slightly surpassing that of the air-annealed counterpart (0.88 mA cm−2)112. Likewise, BiVO4 prepared by various synthetic methods followed by annealing has consistently shown enhanced photoactivity57.

The tz-BiVO4 can also be synthesized via hydrothermal routes through the addition of EDTA-2Na to the precursor solution. EDTA-2Na chelates Bi3+ ions, thereby inducing Bi vacancies in the crystal lattice. These cationic vacancies typically confer p-type semiconductor behavior, as observed in BiVO460. This strategy has been successfully applied to prepare tz-BiVO4 powder and tz-BiVO4/FTO photocathodes, which display excellent PC performance under reductive potentials60,103,113.

Another promising avenue in BiVO4 engineering is the development of two-dimensional (2D) architectures. The cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-induced assembly technique plays a crucial role in the formation of nanosheets114. This method has previously been used to synthesize Bi-nanotubes through the formation of lamellar surfactant/inorganic composite (BiCl4−-CTA+)115. In the case of BiVO4, VO43− ions react with Bi3+ within the lamellar structure via hydrothermal treatment. After washing, impurities such as CTAB and Cl− are removed, yielding pure BiVO4. However, this method primarily yields orthorhombic-BiVO4114, which, as previously discussed, does not exhibit the highest photoactivity.

In recent years, the synthesis of 0D BiVO4 quantum dots (QDs) has gained increasing attention. QD-BiVO4 has been synthesized via the hydrothermal method using sodium oleate as a surfactant, Bi(NO3)3·5H2O as the Bi3+ source, and either Na3VO4·12H2O or NH4VO3 as the VO43− source116,117.

Alternatively, QDs can be obtained through the successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) method, which will be discussed in detail later. Although heterojunctions incorporating BiVO4-QD enhance photo(electro)catalytic activity, pristine BiVO4 QDs have not yet been evaluated in PEC processes or their applications118,119. Moreover, QD-BiVO4 can be synthesized within large metal-organic frameworks, where the precursors are confined within the network, facilitating the formation of BiVO4 crystals with reduced particle size120.

A comprehensive summary of BiVO4 precursors, synthesis methods, and processing conditions is presented in Table 3.

Fabrication of BiVO4 Photoanodes

Electrodeposition

Kim and Choi121 developed an electrodeposition method for BiOI using a plating solution containing Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, KI, and p-benzoquinone at pH 1.75. BiOI is synthesized on the electrode through cathodic potentials, as illustrated in Fig. 13. The reaction between the Bi salt and KI generates the [BiI4]− complex, enhancing solubility. Meanwhile, the reduction of p-benzoquinone to hydroquinone consumes protons, leading to local pH change at the working electrode, thereby facilitating BiOI precipitation. The BiOI-coated electrode is then drop-cast with a VO(acac)2 solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and subsequently calcined to form BiVO4. Any excess V2O5 is removed by washing the electrode with NaOH solution61,121. This method offers several advantages, including the synthesis of nanoporous BiVO4 and the formation of 2D layers using a system relatively simple121,122. Also, Huang et al. reported the formation of twin structures of BiVO4 using this method123. This kind of structure in photocatalysis is of high interest due to its inherent charge separation, which also improves the photoelectrocatalytic behavior.

Adapted from Wang et al.122.

Another electrochemical approach for synthesizing BiVO4 photoanodes uses Bi(NO3)3·5H2O in acetic acid and sodium acetate as a plating solution. Under anodic overpotential, (BiO)4(OH)2CO3 (bismutite) is electrodeposited onto the electrode surface via Kolbe electrolysis. The electrode is then drop-cast with a VO(acac)2 solution and annealed at 520 °C for 2 hours. Any residual V2O5 from the vanadium precursor is removed using a NaOH solution124.

Alternatively, Bi electrodeposition can be used as a precursor step in BiVO4 synthesis. In this approach, Bi(NO3)3·5H2O is dissolved in DMSO as the plating solution, and a reductive potential is applied to deposit Bi particles onto the electrode. The electrode is then dried under a N2 atmosphere with heat before undergoing the same drop-casting and annealing steps as in the previous method125.

Seed layer method

The seed layer technique has emerged as an effective strategy for fabricating high-crystalline-purity BiVO4 photoanodes, leveraging the advantages of the solvo/hydrothermal method. This approach involves the initial deposition of a thin BiVO4 film—designated as the seed layer—onto a conductive substrate, followed by subsequent crystal growth using a secondary method such as hydrothermal treatment. The seed layer is typically prepared from a precursor solution containing Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, NH4VO3, citric acid, and PVA in HNO3. This solution is spread evenly on the electrode by spin coating and then calcined. This process generates the first thin film, appointed as seed (Fig. 14a, step 1). The prepared electrode is then immersed in a hydrothermal growth solution—usually of lower concentration than the seed precursor—to promote layer growth and control film thickness (Fig. 14a, Step 2; Table 3).

Several variations of this technique have been explored. Notably, replacing the hydrothermal step with a reflux reaction has been shown to significantly influence surface morphology. While hydrothermal treatment typically results in a granular surface, reflux-grown films often exhibit faceted structures such as pyramids or rods126,127,128. In the study of Xia et al., chemical bath deposition (CBD) with NaCl was used to promote the formation of BiVO4 photoanodes with dominant (040) facets. The presence of chloride ions selectively adsorbs onto specific crystal planes, thereby directing preferential facet growth129. Further control over crystal orientation has been achieved through the addition of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) during hydrothermal synthesis. Wang et al. reported that PVP facilitates the alignment of the (040) facet parallel to the FTO substrate130. However, Zhang et al. observed that PVP may lead to mixed exposure of (010) and (110) facets, suggesting that the molecular weight of PVP plays a critical role in determining facet selectivity64. Additionally, the same group demonstrated that adjusting the pH of the growth solution to 0.9 under otherwise identical conditions favored the exclusive formation of (110)-oriented BiVO4 photoanodes64.

Successive Ionic Layer Adsorption and Reaction (SILAR) technique

The SILAR method is a widely adopted technique for the surface modification and synthesis of semiconductor materials, including BiVO4. This approach involves the alternate immersion of a substrate into two separate precursor solutions. The first solution typically contains Bi3+ ions as the bismuth source, while the second provides vanadate species (VO₄3−) as the vanadium source. Through sequential dipping, ions are adsorbed onto the substrate surface in a controlled layer-by-layer fashion. Upon exposure to the vanadate-containing solution, the previously adsorbed Bi3+; ions undergo in situ reaction to form BiVO4. Repeating this cycle allows the gradual and uniform deposition of the semiconductor film (Fig. 14b).

An essential post-deposition step in the SILAR process is thermal annealing, which promotes crystallization and enhances the structural integrity of the resulting BiVO4 film131. This high-temperature treatment is critical for achieving high crystallinity and optimizing the material’s photoelectrochemical performance. One of the major advantages of the SILAR method lies in its precise control over film thickness and particle size, both of which play a pivotal role in determining photocatalytic efficiency. For instance, Xie et al. successfully synthesized BiVO4 quantum dots (QD-BiVO4) on SnO2 nanostructures via SILAR, demonstrating the method’s capacity to produce nanoscale materials with tailored properties131.

Beyond BiVO4, the SILAR technique has been effectively employed for the deposition of other photoactive materials such as WO3132 and TiO2133,134, further highlighting its versatility. These studies collectively underscore SILAR’s potential for tuning surface morphology, crystallinity, and optoelectronic properties across a range of photoanode systems. The combination of process simplicity, precision, and compatibility with diverse substrates makes SILAR a compelling method for the fabrication of high-performance photoelectrodes for PEC applications.

Electrospinning and electrospraying techniques for BiVO4 electrode fabrication

Electrospinning is an emerging and effective method for modifying electrodes, enabling the production of nanofibrous materials under the influence of a high-voltage electric field. The technique is considered relatively simple and efficient, as it facilitates the formation of well-structured nanofibers with minimal chemical processing135. In a typical procedure, Bi(NO3)3·5H2O and vanadium(III) tris(acetylacetonate) (C15H21O6V) are dissolved in acetic acid to form a spinnable precursor solution (Fig. 15). The resulting fibers are directly deposited onto a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate and subsequently calcined to yield BiVO4 films136,137.

FESEM image adapted from Rajini et al.139.

An alternative approach involves the use of vanadium(IV) oxyacetylacetonate (VO(acac)2) in place of C15H21O6V, often combined with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as a binding agent. This formulation results in a viscous, homogeneous solution that is readily electrospun onto FTO substrates. Following calcination, the fibrous BiVO4 or co-doped BiVO4 nanostructures exhibit enhanced structural integrity and photocatalytic potential138,139,140,141,142. Among available precursors, VO(acac)2 is currently the most widely used vanadium source in BiVO4 electrospinning.

In addition to electrospinning, electrospraying has also been explored for photoanode fabrication. Swansborough-Aston et al. reported the synthesis of BiVO4 films using bismuth(III) 2-ethylhexanoate as the Bi3+ source and VO(acac)2 as the (VO4)3− source56.

The two precursor solutions were introduced into a mixing chamber and electrosprayed onto a pre-heated FTO substrate. While electrospraying offers control over surface coverage and uniformity, it requires a more sophisticated setup compared to electrospinning. Specifically, a precision syringe pump and high-voltage equipment are essential for generating uniform coatings. Moreover, the use of organic solvents and the relatively high complexity of the apparatus make this technique less environmentally friendly and less economically viable for large-scale electrode modification.

Sputtering and other surface modification techniques

Magnetron sputtering (MS) has recently gained attention as a versatile physical vapor deposition (PVD) technique for modifying photoelectrodes. This method has been employed to fabricate BiVO4-based photoanodes on various substrates, including BDD, demonstrating promising results for PEC applications143,144. This physical deposition method enables the formation of thin layers of materials (e.g., semiconductors) onto various substrates145. MS enables the controlled deposition of thin films by bombarding a target material with high-energy ions—typically argon or helium—generated in a plasma. These ions eject atoms from the target, which then condense onto a substrate to form a uniform coating146,147,148. For BiVO4 deposition, typical precursors include metallic Bi or Bi2O3 as the Bi3+ source, and metallic V or V2O5 for the (VO4)3− source49,149,150.

In addition to direct BiVO4 film formation, sputtering can be used to modify electrode surfaces with high precision143,144. The crystalline phase of the deposited BiVO4 can be tailored using radio frequency (RF) sputtering, a variation of MS that does not require a magnetron. Specifically, high RF power and elevated substrate temperatures favor the formation of ms-BiVO4, whereas lower RF power and temperatures promote the formation of tz-BiVO4. Intermediate conditions can yield a mixed-phase material containing ms-BiVO4, tz-BiVO4, and ts-BiVO4151. This method, the same the last one, requires an expensive equipment to develop it which implies a disadvantage. Despite its advantages in phase control and film uniformity, sputtering techniques require sophisticated and costly equipment, which can be a limiting factor for widespread adoption.

Other less commonly used deposition techniques have also been reported for electrode modification. These include pulsed laser deposition77, hot spin coating152, Langmuir–Blodgett deposition67,153, screen printing for ITO substrates154, and aerosol pyrolysis155. While these methods offer specific advantages, the most commonly adopted approaches for BiVO4-based photoelectrode fabrication remain those discussed in the previous sections.

Doping and heterojunction engineering in BiVO₄-based photoelectrodes

To enhance the PEC performance of BiVO4, several strategies have been investigated, including ionic doping, heterojunction formation, and morphology control. This section focuses on the effects of doping and heterojunction design on improving charge transport and light-harvesting properties in BiVO4 photoanodes.

Doped BiVO4

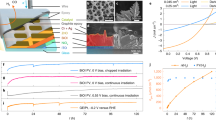

Ionic doping—either with cations or anions—is a well-established approach for modifying the optical and electronic properties of BiVO₄. In particular, the substitution of V5+ with Mo6+ or W6+ has been extensively investigated. These dopants possess oxidation states of +6 and ionic radius comparable to V5+, allowing them to integrate into the vanadium sublattice with minimal disruption to the host structure156,157. The resulting materials, Mo:BiVO4 and W:BiVO4, maintain the monoclinic scheelite-type phase while exhibiting significantly improved PEC activity (Fig. 16a). Since the doping concentration is relatively low, the monoclinic phase of pristine BiVO4 is preserved with minimal structural alterations157.

The incorporation of Mo6+ and W6+ introduces donor levels within the band structure, thereby increasing the charge carrier concentration and enhancing electron mobility156,157. As illustrated in Fig. 16b,c, photoanodes doped with 3–9% Mo or W demonstrate photocurrent densities nearly double that of pristine BiVO4. However, performance declines beyond the optimal doping concentration, likely due to lattice distortion or a reduction in the number of catalytically active surface sites157.

Although both dopants significantly enhance water-splitting performance, Mo:BiVO4 reaches its maximum photocurrent at a lower dopant concentration, as Mo6+ has been identified as a more efficient donor158,159. Additionally, co-doping with Mo6+ and W6+ (Mo/W:BiVO4) has shown synergistic effects, leading to further improvements in PEC performance under optimized conditions. These findings underscore the potential of rational dopant selection and concentration tuning as powerful tools for optimizing BiVO4-based photoelectrodes160.

Beyond Mo and W doping, other elements have been incorporated into BiVO4. For instance, Co:BiVO4161, Co/La:BiVO4161, Er:BiVO4162, Fe/W:BiVO4163, Fe:BiVO4163, La:BiVO4161, Nb:BiVO4164, Ni:BiVO4165, Ta:BiVO4110, Y:BiVO4162, and Zn:BiVO4166 has been reported to enhance conductivity156,166, stability161,163,165,166, wettability (hydrophilicity)166,167, absorption coefficient161,162,165, photocorrosion resistance86, and acidic media resistance86,110. Additionally, anionic doping with halides (F−, Cl−, Br−) has shown slight improvements in PEC performance, with Cl-BiVO4 exhibiting the best results168. Moreover, surface treatments with [B(OH)4]− anions have been found to enhance BiVO4 photoanode performance despite not being incorporated into the crystal lattice169. The presence of such anions in BiVO4 may also create synergic effects when combined with other semiconductors in heterojunctions.

Heterojunctions

Heterojunction engineering is a widely adopted strategy to enhance the PEC performance of BiVO4-based photoanodes. Heterojunctions are formed by coupling two or more semiconductors with distinct bandgap energies (Ebg) and VB and CB alignments. This configuration improves charge separation and transport, thereby minimizing electron–hole recombination and boosting the efficiency of charge utilization74,170. From a physicochemical standpoint, heterojunctions modulate the band edge positions of the constituent semiconductors, enhancing both the oxidation and reduction potential of the system. The resulting band alignment facilitates interfacial charge transfer, enabling the spatial separation of photogenerated charge carriers and extending their lifetime. Depending on the energy band configuration, different heterojunction types—such as Type I, Type II, Z-scheme, etc.—can be designed to optimize redox processes and light-harvesting capabilities. These heterostructures also broaden the light absorption range by combining semiconductors with complementary absorption spectra, allowing more efficient utilization of the solar spectrum. This enhancement translates to higher photocurrent densities and improved PEC performance in applications such as water splitting and photocatalytic pollutant degradation. Notably, the built-in electric field generated at the interface of the heterojunction—within the space charge region—plays a crucial role in driving the photogenerated electrons and holes in opposite directions. This internal field significantly reduces charge recombination and promotes efficient charge migration to reactive sites171.

A detailed overview of heterojunction types and their corresponding charge transfer mechanisms is presented in Table 4, highlighting their structural features and roles in enhancing PEC activity.

Since the degradation of contaminants in photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems is predominantly driven by oxidation processes, heterojunctions are typically engineered on the photoanode. In this configuration, photogenerated electrons are directed toward the cathode via an external circuit, where they participate in reduction reactions. The charge carrier dynamics in PEC systems generally follow similar pathways to those in photocatalytic (PC) heterojunctions, with the notable distinction of being influenced by an applied external potential. For instance, the BiVO4/BiOI interface forms a Type II heterojunction. Following the Type II mechanism, e− in the CB of BiVO4 (CB-BiVO4) are transferred to the external circuit, while h+ in the VB of BiVO4 (VB-BiVO4) migrate to the VB of BiOI, where they engage in oxidation reactions (Table 4, Entry 2)172. In contrast, the BiVO4/Co3Se4 junction exemplifies an S-scheme heterojunction. In this system, electrons in CB-BiVO4 recombine with holes in VB-Co₃Se₄, leaving the remaining holes in VB-BiVO4 to drive oxidation reactions, while electrons in CB-Co3Se4 are transferred to the external circuit or reduce species at the cathode (Table 4, Entry 7). Although schematic representations often show the CB-Co3Se4 spatially distant from the electrode, this is not a literal depiction; the materials used by Yusuf et al. were powders rather than large-area films, implying that certain Co₃Se₄ particles are in direct contact with the electrode, enabling electron transfer173. Similarly, the BiVO4/g-C3N4 photoanode operates via a Z-scheme mechanism (Table 4, Entry 6)174, as described by its authors. In this configuration, h+ accumulate in VB-BiVO4 and electrons in CB-g-C3N4. The photocatalytic performance of this system can be further enhanced by doping g-C3N4 with redox-active metals, as demonstrated by Mafa et al.175. As detailed in BiVO4 properties section, BiVO4 presents anisotropic characteristics, which have effects on the photoelectrochemical behavior. The monoclinic BiVO4 presents a (010) acts as a reductive surface, while the (110) facet is oxidative. The reason these facets have these properties is the surface heterojunction they undergo in the BiVO4 crystal, whereby electrons preferentially migrate to the (010) facet and holes to the (110) facet. This facet-selectivity enables the design of facet-specific heterojunctions, such as Ag/(010)BiVO4107. Additionally, the formation of a twin structure of BiVO4 introduces a series of internal homojunctions that promote charge separation via a “back-to-back” potential mechanism, analogous to that of surface heterojunctions (Table 4, Entry 8)123.

All the aforementioned examples involve binary heterojunctions. In more complex systems containing three or more components, multiple heterojunction types can coexist. For instance, Malefane et al. reported a quadruple-component triple S-scheme structure comprising BiOBr@LaNiO3/CuBi2O4/Bi2WO6176. Dual type II heterojunctions, such as ZnIn2S4/FeOOH/BiVO4 have also been developed by Li et al.177, as well as C-scheme architectures like Co3O4/Bi4O5I2/Bi5O7I by Malefane178, and so on179.

Given that pristine BiVO4 photoanodes are prone to self-passivation86, using a protective layer to prevent direct contact with the solution is an effective strategy to enhance stability and maintain photocurrent. For instance, constructing a heterojunction with NiFeOx on B-doped BiVO4 (B-BiVO4) significantly reduces the loss of photocurrent compared to the bare B-BiVO4 photoanode169. Likewise, incorporating CoPi onto Nb-doped BiVO4 suppresses photocorrosion by preventing the leaching of VOx specie164. Nakajima et al. investigated the BiVO4/WO3 heterojunction in acidic media and proposed that the stability arises from the diffusion of W6+ ions into BiVO4. This induces the migration of Bi3+ to the photoanode surface, forming BiOx nanoparticles that contribute to corrosion resistance180.