Abstract

Lariat-shaped lipopeptides are important antimicrobial agents; however, their complex structures pose synthetic challenges that hamper efficient structural diversification. Here we report a new chemoenzymatic approach that facilitates access to lariat-shaped macrocycles. Unprotected, branched peptides bearing multiple nucleophiles, including a native amino terminus and a pseudo-amino terminus, were site-selectively cyclized using versatile non-ribosomal peptide cyclases, generating an array of lariat peptides with diverse sequences and ring sizes. The generality of this strategy was demonstrated using two penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterases, SurE and WolJ, as well as one type-I thioesterase, TycC thioesterase. Furthermore, the remaining nucleophile, which was not involved in the cyclization process, was exploited as a reactive handle for subsequent diversification via a site-selective acylation reaction (that is, Ser/Thr ligation). The tandem cyclization–acylation strategy enabled the one-pot, modular synthesis of lariat-shaped lipopeptides equipped with various acyl groups. Biological screening revealed that the site-selective acylation endowed the macrocyclic scaffolds with antimycobacterial activity and led to the identification of lipopeptides that inhibit 50% of growth at concentrations of 8–16 µg ml−1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Naturally occurring lariat lipopeptides, featuring a carboxy-terminal macrocyclic head group and a long acyl chain appended to the amino-terminal tail, are among the most important sources of antimicrobial agents with diverse modes of action1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. As examples, daptomycin is used to treat severe infections caused by Gram-positive pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and drug-resistant enterococci, while colistin is used as a last-line-of-defence drug to treat multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. With the continuous rise of antibiotic resistance, there is an urgent need to develop antibiotics with new modes of action. However, the efficient exploration of the rich chemical space of lariat lipopeptides is often hampered by their molecular complexities.

Regioselective ring construction is a typical obstacle for the synthesis of lariat-shaped lipopeptides, requiring an orthogonal protecting group strategy and stoichiometric amounts of coupling reagents6. In addition, the dilute conditions needed to suppress intermolecular coupling involve substantial amounts of organic solvents.

An emerging alternative methodology is the use of enzymes that catalyse peptide cyclization regio-, chemo- or stereoselectively under mild conditions12,13. Most naturally occurring lariat lipopeptides are biosynthesized via a non-ribosomal pathway in which the lariat-shaped macrocyclic scaffolds are typically constructed by type-I thioesterases (TEs), an α/β-hydrolase fold enzyme fused to the C terminus of a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase14,15,16,17. Lariat-forming type-I TEs catalyse selective cyclization using side chain nucleophiles. Unfortunately, in vitro studies have shown that lariat-forming TEs are generally sensitive to changes in the local environment of the nucleophilic residue, including its position, stereochemistry and nucleophilicity18,19,20,21,22,23,24. In addition, the yields of cyclic products are typically low due to the substantial flux of competing hydrolytic reactions. These unfavourable properties have limited the application of lariat-forming TEs in the production of structurally diverse lariat peptides.

Unlike lariat-forming cyclases, some non-ribosomal peptide (NRP) cyclases that catalyse head-to-tail backbone cyclization exhibit exceptional biocatalytic potential. In tyrocidine biosynthesis, TycC thioesterase (TycC-TE) catalyses the cyclization of the native decapeptidyl substrate in a head-to-tail manner, while also tolerating a range of substrate variants with diverse sequences and lengths in vitro25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Similarly, penicillin-binding protein (PBP)-type TEs have recently emerged as a distinct family of NRP cyclases with promising biocatalytic potential36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. The most notable representative is SurE, a macrocyclase in surugamide biosynthesis, which demonstrates broad substrate tolerance for both sequence and length40,44. Using these versatile NRP cyclases, we previously established a facile chemoenzymatic approach in which a simple diol is exploited as a surrogate for the pantetheine leaving group, thereby simplifying the synthesis of enzymatic substrates and streamlining the process (Fig. 1a)44. However, these enzymes preferentially favour heterochiral pairs of ring-closing residues and specifically use α-amine nucleophiles at the N terminus for cyclization, resulting in head-to-tail cyclic peptides. Consequently, the formation of lariat-shaped topologies remains inaccessible to these otherwise versatile NRP cyclases.

a, Schematic summary of the concepts developed in our previous study44 and this study. b, SurE-mediated cyclization of branched substrate 1 bearing two l-aa nucleophiles at the N terminus and on the side chain as a pseudo-N terminus. The Cα atoms of the terminal d-aa and l-aa are coloured magenta and purple, respectively. c, Chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat-shaped peptide 5, involving an enzyme-controlled, regiospecific cyclization. d, HPLC analysis of the enzymatic reaction mixture in the SurE-mediated cyclization of 4. Fmoc, 9-fluorenyl-methoxycarbonyl; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; Boc, tert-butoxycarbonyl; DIC, diisopropylcarbodiimide.

Results

Repurposing a head-to-tail NRP cyclase for lariat peptide synthesis

In this study, we envisioned addressing the lariat topology by leveraging highly versatile head-to-tail NRP cyclases. To this end, we first challenged the head-to-tail specificity of SurE, not by engineering the enzyme itself, but by engineering the shape of the substrates. SurE specifically uses a d-configured C-terminal α-amino acid (aa) and an l-configured N-terminal α-aa. Therefore, to the octapeptide sequence of surugamide B, we introduced an internal dipeptide unit as a ‘pseudo-N terminus’, where l-Ile was attached to the side chain of l-Lys via an isopeptide bond (Fig. 1a). The resultant branched substrate 1, with an ethylene glycol (EG) leaving group at the C terminus, has two N-terminal l-aas, and both could potentially serve as nucleophiles for cyclization (Fig. 1b). Hereafter, the position numbers of the branched chain are described by adding a prime: thus, the position number for the pseudo-N terminus would be 1′. The branched substrate 1 was incubated with 5 mol% SurE at 30 °C. After 3 h, 1 had been completely converted into two distinct products, 2 (60%) and 3 (40%; Extended Data Fig. 1). Tandem mass spectrometry (MS2) demonstrated that 2 is a canonical head-to-tail cyclic peptide, whereas 3 is a lariat-shaped cyclic peptide, formed by the pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ in the dipeptidyl unit acting as a nucleophile for cyclization (Fig. 1b). The two cyclic peptides were formed in comparable amounts, indicating that the pseudo-N terminus is as effective as the native N terminus in serving as a nucleophile for SurE-catalysed cyclization.

Next, we aimed to manipulate the regiospecificity of the cyclization to achieve exclusively the head-to-side chain reaction. PBP-type TEs generally exhibit relaxed specificity towards the N-terminal nucleophile, but strictly recognize its stereochemical configuration, accepting only l-configured residues as nucleophiles, not d-configured residues36,40. Taking advantage of this unique stereospecificity, the native N-terminal residue l-Ile1 was replaced with d-Val to suppress head-to-tail cyclization. The peptide main chain was synthesized on a solid support that was functionalized by EG before solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS)44. The orthogonal protecting group 1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohex-1-ylidene)ethyl (Dde) on the l-Lys3 side chain was removed with 2% hydrazine, and then the pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ was installed on the side chain of l-Lys3 in an additional round of coupling. Resin cleavage and concomitant global deprotection generated the EG-functionalized branched peptide 4 (Fig. 1c), which was then subjected to reaction with SurE, quantitatively producing the lariat-shaped cyclic peptide 5 (Fig. 1d). Notably, although 4 contains three different nucleophiles (that is, N-terminal d-Val1, pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ and ε-NH2 of l-Lys5), no cyclized peptides were generated via d-Val1 or ε-NH2, with the pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ serving exclusively as the nucleophile. These results showed that the regiospecificity of SurE can be switched by altering the stereochemical configuration of nucleophiles, enabling the repurposing of SurE for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat-shaped peptides. The lariat peptide 5 can be obtained by chemical synthesis in a yield of 33% in 19 steps, while the corresponding EG substrate 4 was obtained in 83% yield in 17 steps and then quantitatively cyclized using SurE (Supplementary Table 6), highlighting the advantage of the chemoenzymatic approach.

To obtain mechanistic insights into the regiospecific macrocyclization directed by the stereochemical configuration of the nucleophile, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on a covalent docking model constructed using the crystal structure of apo SurE (Protein Data Bank (PDB): 6KSU) and 1. C-terminal d-Leu8 was set at the previously identified C-terminus binding pocket44, while N-terminal l-Ile1 or pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ was set at the putative nucleophile binding site45: the side chain of l-Ile1/l-Ile1′ was accommodated in the pocket formed by Leu284/Trp288/Met293/His295/Asp306 and the nucleophile amine was hydrogen-bonded to Tyr154, which is thought to abstract a proton48 (Extended Data Fig. 2). l-Ile1 was retained in the nucleophile binding site during 50 ns of MD simulations, and the distance between the l-Ile1 amine and C-terminal d-Leu8 carbonyl carbon was on average 4.5 Å (Extended Data Fig. 3). In contrast, when the configuration of N-terminal l-Ile1 was inverted to d-allo-Ile1, variability in the position of the N terminus was observed in the simulation, and the simulated distance between the nucleophilic amine and C-terminal d-Leu8 carbonyl carbon was much longer, up to over 10 Å, which could account for the unfavourable binding of the d-configured nucleophile (Extended Data Fig. 3). Parallel results were obtained in comparable simulations of docking models in which pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ or d-allo-Ile1′ was bound to the nucleophile binding site (Extended Data Fig. 4). These computational results align well with the observed regiospecificity of SurE for 1 and 4, and suggest that the nucleophile stereoselectivity stems from the spatial arrangement of the side chain-recognizing pocket and proton-abstracting Tyr154 in the nucleophile binding site of SurE.

We next investigated the tolerance of SurE for different pseudo-N terminus positions. To this end, the sequence of 4 was scanned by the l-Ile1′-l-Lys dipeptidyl unit shown in Fig. 2a to give branched EG-functionalized substrates 6–11, with different distances between the pseudo-N terminus and C terminus (Fig. 2b). In 7–11, the native l-Ile1 at the main chain N terminus was substituted with d-Val1 to suppress head-to-tail cyclization. All substrates contained two to three nucleophiles: pseudo-N-terminal l-aa, N-terminal d-aa and/or ε-NH2 of l-Lys. SurE catalysed the cyclization of 6 and 7 to produce near-quantitative yields of the lariat-shaped peptides cyc-6 (31-membered ring) and cyc-7 (28-membered ring), respectively, with ring sizes larger than 5 (25-membered ring; Fig. 2c,d and Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the yield dropped sharply for macrocycles with less than 22 ring atoms. With the expectation of improved reaction yields, the reaction solvent was engineered. The addition of up to 30% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) generally had a positive impact, probably by improving substrate solubility and suppressing hydrolytic flux49,50, and the yields for the formation of lariat-shaped peptides with small rings improved to some extent (for example, from 20% to 55% for 11 with a 13-membered ring). Cyclization occurred exclusively from the pseudo-N terminus in all cases.

a, Structure of the dipeptide unit used to install the pseudo-N terminus. b, Surugamide B-based branched EG-functionalized substrates 6–11 were synthesized to assess the effect of distance between the pseudo-N terminus and C terminus. c, Conversions of 6–11 using SurE in the absence and presence of 30% DMSO. The conversions to macrocyclization (orange) and EG hydrolysis (blue) products are shown. d, Lariat peptides generated by the reactions of 6–11 with SurE. The Cα atoms of d-aa and l-aa at the substrate termini are highlighted by magenta and purple circles, respectively. The ring sizes are indicated in circles in the structures.

To gain insights into the structural basis of the specificity towards the pseudo-N terminus position, the variants of pseudo-N terminus scanning that adopted cyclic conformations were covalently docked onto SurE (PDB: 6KSU). The pseudo-N terminus was set in the nucleophile binding site and the nucleophile amine was directed towards the d-Leu8 carbonyl (Extended Data Fig. 5). Notably, the docked sequences 6, 7 and 4 show interactions with the lipocalin domain that shapes the active site cleft of SurE, while 8–11 apparently lack such contacts (Extended Data Fig. 5). This could account for the distinct cyclization yields achieved according to ring size; however, further insights into protein dynamics (for example, the movement of the lipocalin domain45 and/or the flexible loops in the PBP domain upon substrate binding40) are necessary to clarify the basis of ring-size specificity in detail.

Generality of the chemoenzymatic strategy

To determine whether another head-to-tail NRP cyclase would also be suitable for lariat peptide synthesis, we next investigated WolJ, a PBP-type TE involved in wollamide/desotamide biosynthesis43. WolJ has previously been shown to efficiently cyclize a hexapeptidyl EG substrate in a head-to-tail manner to generate the anti-tuberculosis synthetic cyclic peptide wollamide B1 (ref. 44). As WolJ catalyses macrolactamization using an N-terminal l-Trp, the model wollamide B1 sequence was scanned by the l-Trp1′-l-Lys dipeptidyl unit to generate the branched EG-functionalized substrates 12–16 (Fig. 3a,b), with the N terminus of 13–16 replaced with d-Ala to suppress head-to-tail cyclization. As a result, 12–15 were cyclized to give the corresponding lariat-shaped peptides with 16- to 25-membered rings in various yields, showing that WolJ is also capable of using a pseudo-N terminus for ring closure (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Fig. 2). Notably, WolJ was more amenable to a non-aqueous solvent than SurE, enabling the DMSO content to be increased up to 50%, which led to a marked improvement in the reaction yields. However, the cyclization of 16 to form a 13-membered ring was not tolerated, showing the limitation of WolJ with respect to ring size (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Fig. 2).

a, The structure of the l-Trp1′-l-Lys dipeptide unit used to install the pseudo-N terminus. b, Wollamide B1-based branched EG-functionalized substrates 12–16 were synthesized to assess the effect of distance between the pseudo-N terminus and C terminus. c, Conversions of 12–16 using WolJ in the absence and presence of 50% DMSO. The conversions to macrocyclization (orange) and EG hydrolysis (blue) products are shown. d, Structures of cyc-12–16. The Cα atoms of d-aa and l-aa at the substrate termini are highlighted by magenta and purple circles, respectively. The ring sizes are indicated in circles in the structures. e, TycC-TE-mediated cyclization of the branched substrate 17. The conversion in buffer containing 50% DMSO is indicated. f, Effect of distance between termini on the TycC-TE-mediated cyclization of the branched substrates 18–20. The structure of tyrocidine A is shown for comparison. Conversions are indicated. aYield in buffer excluding DMSO. bYield in buffer containing 50% DMSO. g, WolJ-mediated cyclization of branched substrate 28. The conversion in buffer containing 60% DMSO is indicated. C-terminal Gly is highlighted with a grey circle. h, Structure of wollamide B.

To explore the ability of another member of the NRP cyclase family to generate lariat-shaped peptides from branched substrates, we tested a canonical cis-acting TE (type-I TE), namely TycC-TE. TycC-TE is a TE domain in tyrocidine synthetase that catalyses head-to-tail macrolactamization. Studies have shown its broad substrate tolerance for internal residues25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, while maintaining strict stereospecificity for the nucleophile. Type-I TEs generally exhibit a heterochiral preference for the two ring-closing residues that is opposite to that of PBP-type TEs, that is, TycC-TE tolerates d-Phe1 but not l-Phe1 at the N terminus25. As it accepts the EG leaving group44, we designed the branched, decapeptidyl EG-functionalized substrate 17 bearing an N-terminal l-Phe1 and a pseudo-N-terminal d-Phe1′. Encouragingly, TycC-TE catalysed macrolactamization using exclusively the pseudo-N terminus to generate a lariat-shaped variant of tyrocidine, cyc-17 (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 6). Scanning the tyrocidine sequence with a pseudo-N terminus (that is, the d-Phe1′-l-Lys dipeptidyl unit) revealed that TycC-TE exhibits a moderate scope for lariat ring size, forming lariat peptides with more than 31 ring atoms (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat lipopeptides using acylated substrates

Many lariat-shaped peptides with pharmaceutical relevance, such as daptomycin and colistin, possess lipophilic tails to interact with biological membranes, which are crucial to exert their biological activities5,8,10,11. To investigate the efficacy of our method for producing such lariat-shaped lipopeptides, the N terminus of the branched EG-functionalized substrate of TycC-TE was acylated with a myristoyl group to generate the branched lipopeptidyl EG-functionalized substrate 27. TycC-TE accepted 27 and converted it to the lariat-shaped lipopeptide cyc-27 in 80% yield in the presence of 50% DMSO, demonstrating the suitability of TycC-TE for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat-shaped lipopeptides (Extended Data Fig. 8). Similarly, we tested the suitability of a PBP-type TE for lariat lipopeptide synthesis. Cilagicin is a promising antimicrobial dodeca-lipodepsipeptide with a 34-membered macrocyclic scaffold and a myristic acid chain appended to its N terminus11. Replacing the myristic acid tail with a biphenyl group gave cilagicin-BP with improved in vivo efficacy11. We designated the peptide bond between Gly-l-Tyr as the macrocyclization site. For synthetic convenience, the depsipeptide-forming l-Thr at the branching position was replaced with l-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (l-Dap) to give branched substrate 28, which possesses a bulky biphenyl group appended to d-Ser (Fig. 3g). For the cyclase, we chose WolJ, which can accept a substrate with Gly at the C terminus44. WolJ catalysed the cyclization of 28 to give the cilagicin-BP amide analogue, cyc-28, with 60% conversion in the presence of 60% DMSO (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, cyc-28 differs from wollamide B, the native product of WolJ, in several aspects: sequence, ring size and the presence of a bulky biphenyl group (Fig. 3h). This result shows that the PBP-type TE WolJ is suitable for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat-shaped lipopeptides.

Modular synthesis of lariat lipopeptides by enzymatic macrocyclization and post-cyclization acylation

Although TycC-TE and WolJ tolerate branched substrates with bulky acyl moieties, this approach requires the re-synthesis of the entire substrate from scratch every time that the acyl tail is altered. This laborious process could be bypassed if the tail portion were site-selectively introduced after enzymatic lariat formation. To establish a modular pipeline for rapid structural diversification, we envisioned coupling the presented chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat macrocycles with additional orthogonal reactions that could be directly performed in one pot following the enzymatic reaction. The regioselective cyclization of branched substrates affords products in which the remaining N-terminal nucleophiles that were not involved in cyclization are retained and could potentially be useful as reactive handles. To directly modify the remaining nucleophiles, we coupled enzymatic cyclization with serine/threonine ligation (STL), a selective acylation reaction of an N-terminal Ser/Thr, using salicylaldehyde (SAL) esters as acyl donors51,52. The branched EG-functionalized substrate 29 with an N-terminal d-Ser1 and a pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ was quantitatively converted to the corresponding lariat-shaped peptide cyc-29 using SurE (Extended Data Fig. 9). Incubating the crude enzymatic product with the biphenyl-SAL ester SL021 in a pyridine–acetic acid solution quantitatively converted cyc-29 to an oxazolidine. Successive treatment with 50% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) afforded cyc-29-SL021, a lariat-shaped peptide with a biphenyl moiety (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 9), demonstrating that the tandem cyclization–acylation strategy generates lariat-shaped lipopeptides in one pot from acyclic branched precursors.

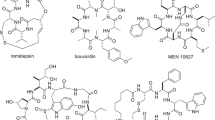

a, The synthetic scheme for the lariat lipopeptide cyc-29-SL021 is shown as an example. After SurE-mediated lariat formation, the enzymatic reaction mixture was directly subjected to STL to introduce the biphenyl group onto the free N-terminal d-Ser that was not used for cyclization. b, The structures of 51 lariat lipopeptides synthesized in this study. The lariat scaffolds (top) and acyl moieties (bottom) are shown. The d- and l-configured terminal residues are highlighted by magenta and purple circles, respectively. The position of the acyl group is shaded in grey. The ring sizes are indicated in circles in the structures.

Harnessing the established facile chemoenzymatic approach, we chemoenzymatically generated two additional lariat-shaped macrocyclic scaffolds with an N-terminal d-Ser1, cyc-30 and cyc-31 (Supplementary Fig. 5), and then synthesized a library of lariat-shaped lipopeptides by combining the three lariat-shaped scaffolds (cyc-29, cyc-30 and cyc-31) with 17 SAL esters to generate 51 samples (Fig. 4b). The pyridine–acetic acid buffer and TFA were removed from the STL reaction mixtures by a simple lyophilization process, which allowed us to evaluate directly the biological activity of the crude reaction products. Thus, we subsequently performed an antimicrobial screening assay on the 51 compounds (17 each from cyc-29, cyc-30 and cyc-31), targeting Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium abscessus, S. aureus and Escherichia coli, all of which are recognized as clinically relevant pathogens. At a concentration of 10 μg ml−1, eight compounds (cyc-30-SL003, cyc-30-SL018, cyc-30-SL021, cyc-30-SL042, cyc-31-SL014, cyc-31-SL016, cyc-31-SL031 and cyc-31-SL032) showed antimicrobial activity exclusively against M. intracellulare, which is one of the most prevalent non-tuberculous Mycobacterium species that cause severe chronic diseases, such as respiratory infections, in immunocompromised patients. These eight compounds and two non-acylated scaffolds, cyc-30 and cyc-31, were chemically synthesized and subjected to detailed evaluation. While the non-acylated scaffolds cyc-30 and cyc-31 exhibited only slight growth inhibition at more than 32 μg ml−1, the introduction of an acyl group substantially enhanced the antimicriobial potency, and the eight compounds inhibited 50% of the growth of M. intracellulare at concentrations of 8–16 µg ml−1 (Extended Data Fig. 10). Although further optimization is required, these findings highlight the effectiveness of our chemoenzymatic strategy for streamlining the library construction and subsequent evaluation of biological activity of the natural product-like lariat-shaped lipopeptides.

Discussion

The versatile head-to-tail NRP cyclases SurE, WolJ and TycC-TE have been repurposed to produce lariat-shaped peptides from branched substrates bearing a pseudo-N terminus. By virtue of the facile synthetic scheme for EG-functionalized substrates that circumvents the need for column purification steps44, an efficient access to lariat-shaped macrocyclic peptides has now been realized. A total synthetic approach to lariat peptide libraries was recently established by Kelly et al.53; however, residues with side chain nucleophiles, which typically require additional deprotection and purification processes, were outside the synthetic scope. In contrast, NRP cyclases accomplish selective macrocyclization in the presence of competing bare nucleophiles, thus offering a unique opportunity to access lariat peptide libraries with greater sequence diversity. Furthermore, the high product specificity allows a modular synthetic workflow to directly diversify the enzymatic products and also streamlines the synthetic process and subsequent evaluation of biological activity. Overall, this study not only highlights the unprecedented level of promiscuity exhibited by certain NRP cyclases but also underscores the remarkable advantages of promiscuous biosynthetic enzymes in addressing natural product-like compound libraries, eventually facilitating rapid hit generation.

Methods

General remarks

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL ECZ 500 (500 MHz for 1H NMR) or JEOL ECZ 400 (400 MHz for 1H NMR) spectrometer. Chemical shifts are given in δ (ppm) relative to residual solvent peaks as internal standard ([2H6]DMSO, δH = 2.50 ppm, δC = 39.5 ppm). Electrospray ionization MS spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Exactive mass spectrometer, a Shimadzu LCMS-2050 spectrometer and a Bruker Daltonics amaZon SL-NPC spectrometer. Optical rotations were recorded on a Jasco P-1030 polarimeter. HPLC experiments were performed on a Shimadzu HPLC system equipped with an LC-20AD intelligent pump. All reagents were used as supplied unless noted otherwise.

Construction of expression plasmids

SurE-pET28a

Detailed procedures for the cloning and expression of recombinant SurE (GenBank: BBZ90014.1) with a His6-tag fused at its N terminus have been reported previously36. Briefly, the DNA fragment coding for SurE was amplified by KOD FX Neo (Toyobo) using forward and reverse SurE as primers (forward SurE: CCGGAATTCCATATGGGTGCCGAGGGGGCG; reverse SurE: CCCAAGCTTTCAGAGCCGGTGCATGGC; restriction enzymes sites are underlined). The genomic DNA of Streptomyces albidoflavus NBRC12854 was used as template. Amplified fragments were digested by EcoRI/HindIII and inserted into the multicloning site of pUC19 (Takara) to give SurE-pUC19 (ref. 36). After conformation of the sequence, the fragment was transferred to the NdeI/HindIII site in the multicloning site of expression vector pET28a (EMD Millipore) to generate SurE-pET28a.

WolJ-pColdII

The DNA fragment encoding codon-optimized WolJ (GenBank: UNO41476.1) was synthesized by Twist Bioscience. The fragment was transferred to the NdeI/HindIII sites of pColdII (Takara) to give WolJ-pColdII, an expression plasmid for WolJ with a His6-tag fused at its N terminus44.

TycC-TE-pET28a

The DNA fragment encoding codon-optimized TycC-TE (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot: O30409.1) with a His6-tag at the C terminus was synthesized by Fasmac. The fragment was transferred to the NdeI/HindIII sites of pET28a to give TycC-TE-pET28a, an expression plasmid for TycC-TE with a His6-tag fused at its N and C termini44.

Enzyme expression and purification

Ampicillin (200 mg ml−1) and kanamycin (50.0 mg ml−1) were used for the selection of the E. coli host harbouring the pColdII- and pET28a-based plasmids, respectively. The expression plasmids were introduced into E. coli BL21 (DE3) and a single colony was inoculated into 10.0 ml of 2xYT media (1.6% Bacto tryptone, 1.0% Bacto yeast extract and 0.5% NaCl) containing the appropriate antibiotic and cultured at 37 °C overnight as seed culture. Then, 2.00 ml cultural broth was transferred to 200 ml 2xYT media containing the appropriate antibiotic and cultured at 37 °C for 3 h. The broth was cooled on ice and 0.1 mM isoproyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to induce the expression of the recombinant enzymes. E. coli was cultured at 16 °C overnight. Cells were washed with wash buffer (20.0 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 150 mM NaCl), then dissolved in lysis buffer (20.0 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole pH 8.0) and successively homogenized by sonication. Cell debris was precipitated by centrifugation at 20,630 g for 20 min at 4 °C and then the supernatant was subjected to Ni nitrilotriacetate His-Bind resin (Merck Millipore), which was equilibrated by lysis buffer. The column was washed with additional lysis buffer and then eluted with elution buffer (20.0 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 500 mM imidazole pH 8.0). Imidazole was removed on an Amicon Ultra 0.5 ml filter (Merck Millipore). The protein concentrations were measured using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit.

In vitro reaction

The reaction conditions used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Liquid chromatography–MS and HPLC analysis

The analytical conditions of LC-MS and HPLC used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 5. The yields of enzymatic reactions were determined by HPLC analysis. The concentrations of the enzymatic products were estimated from their areas, assuming that the extinction coefficients of the EG esters and the corresponding enzymatic products are identical.

Liquid chromatography–MS2 analysis

Samples were separated using a Shimadzu HPLC system equipped with an LC-20AD intelligent pump. The HPLC system was operated under analytical conditions 4 (see Supplementary Table 5 for details). Liquid chromatography–MS2 experiments were performed on a Bruker Daltonics amaZon SL-NPC spectrometer using helium gas and an amplitude value of 1.0 V.

General procedure for SPPS

Step 1

The Fmoc group of the solid-supported peptide was removed using 20% piperidine–DMF (10 min, room temperature), followed by a 93:2:5 solution of DMF–1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene–piperidine (5 min, room temperature).

Step 2

The resin in the reaction vessel was washed with DMF (×3) and CH2Cl2 (×3).

Step 3

DIC (4 equiv. in DMF) and Oxyma (4 equiv. in DMF) were added to a solution of Fmoc-protected building blocks (4 equiv.). After pre-activation for 2–3 min, the mixture was injected into the reaction vessel and the resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min at 37 °C.

Step 4

The resin in the reaction vessel was washed with DMF (×3) and CH2Cl2 (×3). Amino acids were condensed onto the solid support by repeating steps 1–4.

Quantification of the loading rate in SPPS

The resin was dried under vacuum for 1 h to give Fmoc-X-Trt(2-Cl) or Fmoc-X-EG-Trt(2-Cl) resin, where X denotes amino acids and Trt represents a trityl group). The dried resin was then added to a mixture of 20% piperidine in DMF (1.00 ml) and stirred for 1 h. The supernatant was diluted 100-fold with DMF and then subjected to UV measurement at 301 nm. The loading rate (mmol g−1) was calculated from the UV absorbance as follows:

where A301 is the UV absorbance at 301 nm and Mresin is the mass of the resin used for quantification.

Synthesis of branched EG substrates

Details of the synthesis of branched EG substrates are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Docking studies for the SurE–peptide complex models by simulated annealing approach

Docking calculations were carried out using AutoDock4 (ref. 54). The crystal structure of SurE (PDB: 6KSU)40 was used as the receptor. The docking process was performed using the following procedure. (1) N-Acetyl-d-Leu mimicking C-terminal d-Leu8 was covalently docked onto Ser63 of the receptor. Polar hydrogen atoms were included in the models. The search area included the hydrophobic pocket comprising Ala227/Leu231/Ala232/Ala234/Gly235/Gly236/Gly307/Ala308/Val309, which is involved in the recognition of the substrate C terminus44. Then, 100 independent dockings were performed and the pose with productive interactions was obtained for later manipulation. (2) (S)-2-Amino-N,4-dimethylpentanamide mimicking N-terminal l-Ile1 was docked onto the receptor. Polar hydrogen atoms were included in the models. The search area included the putative binding site of the substrate N terminus, which comprises Leu284/Trp288/Met293/His295/Asp306 (ref. 45). Then, 100 independent dockings were performed and the pose with productive interactions was obtained for later manipulation. (3) The internal sequences of the substrate were carefully modelled without moving the N- and C-terminal residues. (4) Conformational sampling of the modelled substrate was performed by simulated annealing using the GROMACS 2023 software package55. The AMBER ff14SB force field was used for canonical amino acids, and the Generalized AMBER Force Field (GAFF) parameters were used for non-canonical bonds (that is, the ester bond connecting D-Leu8 and Ser63, and the isopeptide bond in the dipeptidyl units). Missing loops were modelled using MODELLER56. The complex was solvated with transferable intermolecular potential with 3 points (TIP3P) water in a cubic box (83 × 89 × 94 Å3) under periodic boundary conditions. The simulated annealing comprised 100 cycles of 300 ps. Each cycle consisted of (1) 45 ps to equilibrate the temperature at 300 K, (2) in the following 10 ps, the temperature was immediately increased to 1,000 K and maintained at this temperature for 145 ps, (3) the system was slowly cooled from 1,000 K to 300 K through 100 ps and (4) when the system reached 300 K, the coordinates were saved as the final conformation. During the simulation, the atoms of the receptor and N- and C-terminal residues were fixed by harmonic position restraints with 10 kcal mol−1 Å−2 position restriction. After the 100 cycles, the sampled poses were evaluated using the scoring function of AutoDock4 (ref. 54). The peptide ligand tethered to the catalytic Ser63 was treated as flexible and all other residues in the receptor were treated as rigid. The binding energy of the residues in the cyclic moiety was calculated using the epdb option of AutoDock4 (ref. 54) and the top ten poses for each peptide were analysed using Pymol57.

MD simulations

The AMBER ff14SB force field was used for canonical amino acids, and the Generalized AMBER Force Field (GAFF) parameters were used for non-canonical bonds (that is, the ester bond connecting D-Leu8 and Ser63, and the isopeptide bond in the dipeptidyl units). The protein was protonated by the H++ server (pH 8.0)58. The protein and ligand structures were solvated with TIP3P water in a cubic box (84 × 90 × 94 Å3) under periodic boundary conditions. Na+ or Cl− ions were included to neutralize the protein charge, then further ions were added corresponding to a salt solution of concentration 0.15 M. The protocols for energy minimization and equilibration of the system have been reported previously59. After equilibration, a production run was performed for each protonated state in the NPT ensemble (the isothermal-isobaric ensemble) at 300 K for 50 ns. Coordinates were saved every 10 ps. Distance restraints between the N-terminal nucleophilic nitrogen atom and C-terminal d-Leu8 carbon atom and also between the N-terminal nucleophilic nitrogen atom and the phenolic hydroxy group of the proposed catalytic base Tyr154 (ref. 48) were applied during equilibration and the first 10 ns of a production run. These MD simulations were performed using the GROMACS 2023 software package55.

Bacterial strains

M. intracellulare JCM 6384 was obtained from the Japan Collection of Microorganisms, and M. abscessus ATCC 19977, S. aureus ATCC 29213 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. These strains were used in the screening of 51 potential antimicrobial compounds, with 17 each derived from cyc-29, cyc-30 and cyc-31.

Screening assay for antimicrobial compounds

For the primary screening based on antimicrobial activity, each compound was prepared at a final concentration of 100 mg ml−1 in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 5% OADC (0.06% (v/v) oleic acid, 5.0% (w/v) bovine albumin (Fraction V), 2.0% (w/v) dextrose 0.003% (w/v) catalase and 0.85% sodium chloride) for M. intracellulare and in cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth for the other bacterial species. Then, 50 ml of the compound-containing medium was dispensed into each well of a sterile 96-well microtitre plate followed by 50 ml of bacterial suspension, resulting in a final volume of 100 µl per well (~5 × 105 cells ml−1). All bacterial cultures were incubated at 37 °C for the following periods: M. intracellulare for 14 days, M. abscessus for 72 h, and S. aureus and E. coli for 20 h. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured using a VICTOR Nivo microplate reader (Revvity). Compounds that inhibited bacterial growth by ≥50%, as indicated by an OD600 value ≤50% of the DMSO control, were considered to exhibit antimicrobial activity. Bacterial strains and compounds exhibiting such activity at 100 mg ml−1 were subjected to a secondary screening at 10 mg ml−1 under the same culture conditions. Compounds exhibiting antimicrobial activity at 10 mg ml−1 were further evaluated in growth inhibition curve assays.

Growth inhibition curve assay

Bacterial cultures containing antimicrobial compounds at final concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 128 mg ml−1 were incubated at 37 °C under the same culture conditions as described above, after which the OD600 was measured. The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated using the formula [1 − (sample OD/control OD)] × 100, where ‘sample OD’ represents the OD of the treated well and ‘control OD’ refers to the OD of the compound-free control well on the same plate. Growth inhibition curves were plotted according to a previously reported method60. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Data availability

MS2 and NMR spectra are provided in the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Schneider, T. et al. The lipopeptide antibiotic friulimicin B inhibits cell wall biosynthesis through complex formation with bactoprenol phosphate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 1610–1618 (2009).

Rubinchik, E. et al. Mechanism of action and limited cross-resistance of new lipopeptide MX-2401. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 2743–2754 (2011).

Raaijmakers, J. M., De Bruijn, I., Nybroe, O. & Ongena, M. Natural functions of lipopeptides from Bacillus and Pseudomonas: more than surfactants and antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 1037–1062 (2010).

Hamley, I. W. Lipopeptides: from self-assembly to bioactivity. Chem. Commun. 51, 8574–8583 (2015).

Kleijn, L. H. et al. Total synthesis of laspartomycin C and characterization of its antibacterial mechanism of action. J. Med. Chem. 59, 3569–3574 (2016).

Wood, T. M. & Martin, N. I. The calcium-dependent lipopeptide antibiotics: structure, mechanism, & medicinal chemistry. Med. Chem. Commun. 10, 634–646 (2019).

Grein, F. et al. Ca2+-daptomycin targets cell wall biosynthesis by forming a tripartite complex with undecaprenyl-coupled intermediates and membrane lipids. Nat. Commun. 11, 1455 (2020).

Oluwole, A. O. et al. Lipopeptide antibiotics disrupt interactions of undecaprenyl phosphate with UptA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2408315121 (2024).

Hover, B. M. et al. Culture-independent discovery of the malacidins as calcium-dependent antibiotics with activity against multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 415–422 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. A naturally inspired antibiotic to target multidrug-resistant pathogens. Nature 601, 606–611 (2022).

Wang, Z., Koirala, B., Hernandez, Y., Zimmerman, M. & Brady, S. F. Bioinformatic prospecting and synthesis of a bifunctional lipopeptide antibiotic that evades resistance. Science 376, 991–996 (2022).

Schmidt, M., Toplak, A., Quaedflieg, P. J. L. M., van Maarseveen, J. H. & Nuijens, T. Enzyme-catalyzed peptide cyclization. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 26, 11–16 (2017).

Qiao, S., Cheng, Z. & Li, F. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of macrocyclic peptides and polyketides via thioesterase-catalyzed macrocyclization. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 20, 721–733 (2024).

Horsman, M. E., Hari, T. P. & Boddy, C. N. Polyketide synthase and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase thioesterase selectivity: logic gate or a victim of fate? Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 183–202 (2016).

Little, R. F. & Hertweck, C. Chain release mechanisms in polyketide and non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 39, 163–205 (2022).

Adrover-Castellano, M. L., Schmidt, J. J. & Sherman, D. H. Biosynthetic cyclization catalysts for the assembly of peptide and polyketide natural products. ChemCatChem 13, 2095–2116 (2021).

Matsuda, K. Macrocyclizing-thioesterases in bacterial non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis. J. Nat. Med. 79, 1–14 (2025).

Tseng, C. C. et al. Characterization of the surfactin synthetase C-terminal thioesterase domain as a cyclic depsipeptide synthase. Biochemistry 41, 13350–13359 (2002).

Sieber, S. A., Walsh, C. T. & Marahiel, M. A. Loading peptidyl-coenzyme A onto peptidyl carrier proteins: a novel approach in characterizing macrocyclization by thioesterase domains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 10862–10866 (2003).

Grünewald, J., Sieber, S. A., Mahlert, C., Linne, U. & Marahiel, M. A. Synthesis and derivatization of daptomycin: a chemoenzymatic route to acidic lipopeptide antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 17025–17031 (2004).

Grünewald, J., Sieber, S. A. & Marahiel, M. A. Chemo- and regioselective peptide cyclization triggered by the N-terminal fatty acid chain length: the recombinant cyclase of the calcium-dependent antibiotic from Streptomyces coelicolor. Biochemistry 43, 2915–2925 (2004).

Sieber, S. A., Tao, J., Walsh, C. T. & Marahiel, M. A. Peptidyl thiophenols as substrates for nonribosomal peptide cyclases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 493–498 (2004).

Zhong, W., Budimir, Z. L., Johnson, L. O., Parkinson, E. I. & Agarwal, V. Activity and biocatalytic potential of an indolylamide generating thioesterase. Org. Lett. 26, 9378–9382 (2024).

Maruyama, H., Yamada, Y., Igarashi, Y., Matsuda, K. & Wakimoto, T. Enzymatic peptide macrocyclization via indole-N-acylation. Chem. Sci. 16, 3872–3877 (2025).

Trauger, J. W., Kohli, R. M., Mootz, H. D., Marahiel, M. A. & Walsh, C. T. Peptide cyclization catalysed by the thioesterase domain of tyrocidine synthetase. Nature 407, 215–218 (2000).

Trauger, J. W., Kohli, R. M. & Walsh, C. T. Cyclization of backbone-substituted peptides catalyzed by the thioesterase domain from the tyrocidine nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Biochemistry 40, 7092–7098 (2001).

Kohli, R. M., Trauger, J. W., Schwarzer, D., Marahiel, M. A. & Walsh, C. T. Generality of peptide cyclization catalyzed by isolated thioesterase domains of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 40, 7099–7108 (2001).

Kohli, R. M., Walsh, C. T. & Burkart, M. D. Biomimetic synthesis and optimization of cyclic peptide antibiotics. Nature 418, 658–661 (2002).

Xie, G. et al. Substrate spectrum of tyrocidine thioesterase probed with randomized peptide N-acetylcysteamine thioesters. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 12, 989–992 (2002).

Lin, H., Thayer, D. A., Wong, C. H. & Walsh, C. T. Macrolactamization of glycosylated peptide thioesters by the thioesterase domain of tyrocidine synthetase. Chem. Biol. 11, 1635–1642 (2004).

Kohli, R. M., Takagi, J. & Walsh, C. T. The thioesterase domain from a nonribosomal peptide synthetase as a cyclization catalyst for integrin binding peptides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1247–1252 (2002).

Garbe, D., Sieber, S. A., Bandur, N. G., Koert, U. & Marahiel, M. A. Enzymatic cyclisation of peptidomimetics with incorporated (E)-alkene dipeptide isosteres. ChemBioChem 5, 1000–1003 (2004).

Mukhtar, T. A., Koteva, K. P. & Wright, G. D. Chimeric streptogramin-tyrocidine antibiotics that overcome streptogramin resistance. Chem. Biol. 12, 229–235 (2005).

Kohli, R. M., Burke, M. D., Tao, J. & Walsh, C. T. Chemoenzymatic route to macrocyclic hybrid peptide/polyketide-like molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7160–7161 (2003).

Lin, H. & Walsh, C. T. A chemoenzymatic approach to glycopeptide antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13998–14003 (2004).

Kuranaga, T. et al. Total synthesis of the nonribosomal peptide surugamide B and identification of a new offloading cyclase family. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 9447–9451 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Investigation of penicillin binding protein (PBP)-like peptide cyclase and hydrolase in surugamide non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis. Cell Chem. Biol. 26, 737–744 (2019).

Thankachan, D. et al. A trans-acting cyclase offloading strategy for nonribosomal peptide synthetases. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 845–849 (2019).

Matsuda, K. et al. SurE is a trans-acting thioesterase cyclizing two distinct non-ribosomal peptides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 1058–1061 (2019).

Matsuda, K. et al. Heterochiral coupling in non-ribosomal peptide macrolactamization. Nat. Catal. 3, 507–515 (2020).

Matsuda, K., Fujita, K. & Wakimoto, T. PenA, a penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterase specialized for small peptide cyclization. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 48, kuab023 (2021).

Fazal, A., Wheeler, J., Webb, M. E. & Seipke, R. F. The N-terminal substrate specificity of the SurE peptide cyclase. Org. Biomol. Chem. 20, 7232–7235 (2022).

Booth, T. J. et al. Bifurcation drives the evolution of assembly-line biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 3498 (2022).

Kobayashi, M., Fujita, K., Matsuda, K. & Wakimoto, T. Streamlined chemoenzymatic synthesis of cyclic peptides by non-ribosomal peptide cyclases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3270–3275 (2023).

Budimir, Z. L. et al. Biocatalytic cyclization of small macrolactams by a penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 120–128 (2024).

Matsuda, K., Ichihara, R. & Wakimoto, T. FlkO, a penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterase in cyclofaulknamycin biosynthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 22, 6713–6717 (2024).

Kobayashi, M., Onozawa, N., Matsuda, K. & Wakimoto, T. Chemoenzymatic tandem cyclization for the facile synthesis of bicyclic peptides. Commun. Chem. 7, 67 (2024).

Du, Z. et al. Exploring the substrate stereoselectivity and catalytic mechanism of nonribosomal peptide macrocyclization in surugamides biosynthesis. iScience 27, 108876 (2024).

Yeh, E., Lin, H., Clugston, S. L., Kohli, R. M. & Walsh, C. T. Enhanced macrocyclizing activity of the thioesterase from tyrocidine synthetase in presence of nonionic detergent. Chem. Biol. 11, 1573–1582 (2004).

Wagner, B., Sieber, S. A., Baumann, M. & Marahiel, M. A. Solvent engineering substantially enhances the chemoenzymatic production of surfactin. ChemBioChem 7, 595–597 (2006).

Li, X., Lam, H. Y., Zhang, Y. & Chan, C. K. Salicylaldehyde ester-induced chemoselective peptide ligations: enabling generation of natural peptidic linkages at the serine/threonine sites. Org. Lett. 12, 1724–1727 (2010).

Kaguchi, R. et al. Discovery of biologically optimized polymyxin derivatives facilitated by peptide scanning and in situ screening chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3665–3681 (2023).

Kelly, C. N. et al. Geometrically diverse lariat peptide scaffolds reveal an untapped chemical space of high membrane permeability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 705–714 (2021).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexiblity. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1, 19–25 (2015).

Fiser, A., Do, R. K. & Sali, A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 9, 1753–1773 (2000).

DeLano, W. L. CCP4 Newsletter on Protein Crystallography No. 40; 82–92 (CCP4, 2002).

Gordon, J. C. et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W368–W371 (2005).

Moriwaki, Y. et al. Biochemistry 52, 8866–8877 (2013).

Saez-Lopez, E. et al. Amoxicillin/clavulanate in combination with rifampicin/clarithromycin is bactericidal against Mycobacterium ulcerans. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0011867 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by Hokkaido University, Global Facility Center (GFC), Pharma Science Open Unit (PSOU), funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) under ‘Support Program for Implementation of New Equipment Sharing System’ (T.W., K.M., A.K. and S.I.), the Global Station for Biosurfaces and Drug Discovery, a project of the Global Institution for Collaborative Research and Education at Hokkaido University (T.W., K.M., A.K. and S.I.), the Japan Foundation for Applied Enzymology (T.W.), the TERUMO Life Science Foundation (K.M.), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP25ak0101256 (T.W.), JP25gm1610007 (K.M., H.F., Y.H. and A.H.) and JP25ama121039 (T.W.)), Grants-in-Aid from MEXT, the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST grant nos. ACT-X JPMJAX201F (K.M.), FOREST JPMJFR233U (K.M.), A-STEP JPMJTR24U6 (T.W.) and SPRING JPMJSP2119 (Y.Y.)), and JSPS KAKENHI (grant nos. JP21H02635 (T.W.), JP22K15302 (K.M.), JP22H05128 (T.W.), JP22KJ0097 (M.K.), JP23K17410 (K.M.), JP24K01659 (K.M.) and JP25H00907 (T.W.))

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K., K.M. and T.W. designed the whole study. M.K., K.M., Y.Y., R.I. and N.O. performed the experiments, including the chemical syntheses, enzyme assay, data analysis, docking analysis and MD simulations. H.F., Y.H., A.H. and M.S. performed the biological assay. A.K. and S.I. performed chemical syntheses. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks Ryan Seipke and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 2 The binding sites for substrate termini in SurE.

a. The docking model of terminal residues. Residues on the surface are shown in orange sticks. N-acetyl-d-Leu covalently docked to Ser63 is mimicking the C-terminal d-Leu8 (‘d-Leu8’ shown in green), and bound to the hydrophobic pocket consisting of A227/L231/A232/A234/G235/G236/G307/A308/V309, which is involved in the recognition of the substrate C terminus40,44. (S)-2-amino-N,4-dimethylpentanamide mimicking N-terminal L-Ile1 (‘L-Ile1’ shown in cyan) is bound to the putative N terminus binding site, which consists of L284/W288/M293/H295/D306. This site is equivalent to the site that binds N-terminal L-Trp in the covalent docking model of Ulm16 and desotamide A45. The interaction between the ‘L-Leu1’ amine and Y154, which is proposed to act as a catalytic base48, is shown as a dashed yellow line. b. The putative N terminus binding site of SurE shown from a different angle. c. The equivalent site in Ulm16, where N-terminal L-Trp in the covalent docking model of Ulm16-desotamide A was bound45. Residues that form the binding pocket are shown in blue sticks.

Extended Data Fig. 3 MD simulation of the docking model of SurE (6KSU) in complex with the branched peptide part of 1 that is tethered on the catalytic Ser63.

N-terminal residue (l-Ile1 or d-allo-Ile1) is set at the N terminus binding site in the initial pose. The branched peptides with the N-terminal l-Ile1 and d-allo-Ile1 are shown in green and yellow, respectively. Gray dots indicate the distance between the N-terminal Ile1 nitrogen atom and the C-terminal d-Leu8 carbonyl carbon atom. a. The snapshot of the model with the N-terminal l-Ile1 at 0 ns. b. The snapshot of the model with the N-terminal d-allo-Ile1 at 0 ns. c. The snapshot of the model with the N-terminal l-Ile1 at 10 ns. d. The snapshot of the model with the N-terminal d-allo-Ile1 at 10 ns. e. The snapshot of the model with the N-terminal l-Ile1 at 60 ns. f. The snapshot of the model with the N-terminal d-allo-Ile1 at 60 ns. g. Plot of the distance between the N-terminal nitrogen atom (l-Ile1 N or d-allo-Ile1 N) and the C-terminal d-Leu8 carbon atom (d-Leu8 C). The initial 10 ns of a production run with distance restraints is shown in grey shading.

Extended Data Fig. 4 MD simulation of the docking model of SurE (6KSU) in complex with the branched peptide part of 1 that is tethered on the catalytic Ser63.

Pseudo-N-terminal residue (l-Ile1′ or d-allo-Ile1′) is set at the N terminus binding site in the initial pose. The branched peptides with the pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ and d-allo-Ile1′ are shown in cyan and pink, respectively. Grey dots indicate the distance between the pseudo-N-terminal Ile1′ nitrogen atom and the C-terminal d-Leu8 carbonyl carbon atom. a. The snapshot of the model with the pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ at 0 ns. b. The snapshot of the model with the pseudo-N-terminal d-allo-Ile1′ at 0 ns. c. The snapshot of the model with the pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ at 10 ns. d. The snapshot of the model with the pseudo-N-terminal d-allo-Ile1′ at 10 ns. e. The snapshot of the model with the pseudo-N-terminal l-Ile1′ at 60 ns. f. The snapshot of the model with the pseudo-N-terminal D-allo-Ile1′ at 60 ns. g. Plot of the distance between the pseudo-N-terminal nitrogen atom (l-Ile1′ N or d-allo-Ile1′ N) and the C-terminal d-Leu8 carbon atom (d-Leu8 C). The initial 10 ns of a production run with distance restraints is shown in grey shading.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The covalent docking models of SurE and the branched peptides 4, 6–11.

Overall structures and active sites of docking models are shown in left and right panels, respectively. Protein surface of PBP domain and lipocalin domain are shown in gray and light green, respectively. Residues that are pre-organized to cyclic conformation are shown as opaque. Branched peptides corresponding to 6 (a), 7 (b), 4 (c), 8 (d), 9 (e), 10 (f), and 11 (g) tethered to the catalytic Ser63 are shown in green, cyan, magenta, yellow, pink, purple, and orange, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Pseudo-N terminus scanning of the tyrocidine sequence.

The structure of the d-Phe1′-l-Lys dipeptide unit, the branched EG substrates (18–26), and the cyclization/hydrolysis conversion mediated by TycC-TE are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Chemoenzymatic synthesis of a lariat lipopeptide via enzymatic lariat formation followed by Ser/Thr ligation for site-selective acylation.

a. Synthetic scheme of the lariat lipopeptide cyc-29-SL021. d- and l-configured terminal residues are highlighted with magenta and purple circles, respectively. b. HPLC analysis of reaction products at each synthetic step. Trace A: SurE reaction mixture using 29 as a substrate. Reactions were performed under reaction condition 5, as listed in Supplementary Table 4. Trace B: Reaction mixture after incubation with SL021 in pyridine/acetic acid buffer. The oxazolidine was marked with an asterisk. Trace C: Reaction mixture after TFA treatment. Samples were analyzed under analytical condition 4, as listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Anti-mycobacterial activity of lariat lipopeptides.

Growth inhibition rates (%) of Mycobacterium intracellulare JCM 6384 following treatment with (a) cyc-30-based lariat peptides and (b) cyc-31-based lariat peptides. Acyl groups are highlighted in red.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Tables 1–7 and Figs. 1–145.

Source data

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Unprocessed optical density data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kobayashi, M., Matsuda, K., Yamada, Y. et al. Non-ribosomal peptide cyclase-directed chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat lipopeptides. Nat. Chem. 18, 180–188 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01979-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01979-6