Abstract

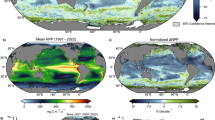

Terrestrial and marine ecosystems constitute the primary components of the Earth’s biosphere, yet their photosynthetic productions are typically studied separately, which limits understanding of planetary carbon uptake and biosphere health. Here, using multiple satellite-derived products, we identify contrasting net primary production (NPP) trends between land and ocean, probably reflecting their differential sensitivity to climate warming, especially in tropical regions. Planetary NPP shows an overall increase of 0.11 ± 0.13 PgC yr−1 (P = 0.05) from 2003 to 2021, driven by a significant terrestrial enhancement of 0.20 ± 0.07 PgC yr−1 (P < 0.001) and partially offset by an oceanic decline of −0.12 ± 0.12 PgC yr−1 (P = 0.07). While land contributes to the strong upwards NPP trend, the interannual variability in global NPP is predominantly driven by the ocean, especially during strong El Niño–Southern Oscillation events. Our findings highlight the resilience and potential vulnerability of biosphere primary productivity in a warming climate, calling for integrated land–ocean monitoring and assessment to support climate mitigation initiatives.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All global satellite and geophysical products needed to evaluate the conclusions in this article are publicly available, with their respective access links provided in Supplementary Table 1. The generated global land and ocean means and their annual trends and significance from 2003 to 2021 are available via the Open Science Framework repository73. An interactive tool for the visualization of the key global NPP metrics including multiyear mean, annual trend, interannual variability and specific yearly anomaly is available online74.

Code availability

All codes needed to reproduce the key findings in this article are available via the Open Science Framework repository73.

References

Steffen, W. et al. The emergence and evolution of Earth System Science. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 54–63 (2020).

Field, C. B., Behrenfeld, M. J., Randerson, J. T. & Falkowski, P. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281, 237–240 (1998).

O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F. & Steinberger, J. K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 1, 88–95 (2018).

Gruber, N. et al. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 119–134 (2023).

Ruehr, S. et al. Evidence and attribution of the enhanced land carbon sink. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 518–534 (2023).

Zeng, Z. et al. Climate mitigation from vegetation biophysical feedbacks during the past three decades. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 432–436 (2017).

Behrenfeld, M. J. et al. Biospheric primary production during an ENSO transition. Science 291, 2594–2597 (2001).

Crisp, D. et al. How well do we understand the land–ocean–atmosphere carbon cycle? Rev. Geophys. 60, e2021RG000736 (2022).

Zhao, M. & Running, S. W. Drought-induced reduction in global terrestrial net primary production from 2000 through 2009. Science 329, 940–943 (2010).

O’Sullivan, M. et al. Climate‐driven variability and trends in plant productivity over recent decades based on three global products. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2020GB006613 (2020).

Piao, S. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 14–27 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Earth’s record-high greenness and its attributions in 2020. Remote Sens. Environ. 316, 114494 (2025).

Novick, K. A. et al. The impacts of rising vapour pressure deficit in natural and managed ecosystems. Plant Cell Environ. 47, 3561–3589 (2024).

Li, F. et al. Global water use efficiency saturation due to increased vapor pressure deficit. Science 381, 672–677 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Song, C., Band, L. E. & Sun, G. No proportional increase of terrestrial gross carbon sequestration from the greening earth. JGR Biogeosci. 124, 2540–2553 (2019).

Behrenfeld, M. J. et al. Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity. Nature 444, 752–755 (2006).

Westberry, T. K., Silsbe, G. M. & Behrenfeld, M. J. Gross and net primary production in the global ocean: an ocean color remote sensing perspective. Earth Sci. Rev. 237, 104322 (2023).

Gregg, W. W. & Rousseaux, C. S. Global ocean primary production trends in the modern ocean color satellite record (1998–2015). Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 124011 (2019).

Ryan-Keogh, T. J., Tagliabue, A. & Thomalla, S. J. Global decline in net primary production underestimated by climate models. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 75 (2025).

Ryan-Keogh, T. J., Thomalla, S. J., Chang, N. & Moalusi, T. A new global oceanic multi-model net primary productivity data product. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 4829–4848 (2023).

Chen, J. M. et al. Vegetation structural change since 1981 significantly enhanced the terrestrial carbon sink. Nat. Commun. 10, 4259 (2019).

Yu, T. et al. Estimation of global vegetation productivity from global land surface satellite data. Remote Sens. 10, 327 (2018).

Endsley, K. A., Zhao, M., Kimball, J. S. & Devadiga, S. Continuity of global MODIS terrestrial primary productivity estimates in the VIIRS era using model‐data fusion. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 128, e2023JG007457 (2023).

Ito, A. A historical meta‐analysis of global terrestrial net primary productivity: are estimates converging? Glob. Change Biol. 17, 3161–3175 (2011).

Westberry, T., Behrenfeld, M. J., Siegel, D. A. & Boss, E. Carbon‐based primary productivity modeling with vertically resolved photoacclimation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22, 1–18 (2008).

Silsbe, G. M., Behrenfeld, M. J., Halsey, K. H., Milligan, A. J. & Westberry, T. K. The CAFE model: a net production model for global ocean phytoplankton. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 1756–1777 (2016).

Brewin, R. J. et al. Sensing the ocean biological carbon pump from space: a review of capabilities, concepts, research gaps and future developments. Earth Sci. Rev. 217, 103604 (2021).

Seiler, C. et al. Are terrestrial biosphere models fit for simulating the global land carbon sink? J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002946 (2022).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 5301–5369 (2023).

Román, M. O. et al. Continuity between NASA MODIS collection 6.1 and VIIRS collection 2 land products. Remote Sens. Environ. 302, 113963 (2024).

McClain, C. R., Franz, B. A. & Werdell, P. J. Genesis and evolution of NASA’s satellite ocean color program. Front. Remote Sens. 3, 938006 (2022).

Terhaar, J. et al. Assessment of global ocean biogeochemistry models for ocean carbon sink estimates in RECCAP2 and recommendations for future studies. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 16, e2023MS003840 (2024).

Keenan, T. F. & Riley, W. J. Greening of the land surface in the world’s cold regions consistent with recent warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 825–828 (2018).

Li, G. et al. Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 1116–1123 (2020).

Sallée, J.-B. et al. Summertime increases in upper-ocean stratification and mixed-layer depth. Nature 591, 592–598 (2021).

Moore, J. K. et al. Sustained climate warming drives declining marine biological productivity. Science 359, 1139–1143 (2018).

D’Alelio, D. et al. Machine learning identifies a strong association between warming and reduced primary productivity in an oligotrophic ocean gyre. Sci. Rep. 10, 3287 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Ocean-scale patterns of environment and climate changes driving global marine phytoplankton biomass dynamics. Sci. Adv. 10, eadm7556 (2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 791–795 (2016).

Chen, S. et al. Amazon forest biogeography predicts resilience and vulnerability to drought. Nature 631, 111–117 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Global fire modelling and control attributions based on the ensemble machine learning and satellite observations. Sci. Remote Sens. 7, 100088 (2023).

Thomalla, S. J., Nicholson, S.-A., Ryan-Keogh, T. J. & Smith, M. E. Widespread changes in Southern Ocean phytoplankton blooms linked to climate drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 975–984 (2023).

Lewis, K. M., Van Dijken, G. L. & Arrigo, K. R. Changes in phytoplankton concentration now drive increased Arctic Ocean primary production. Science 369, 198–202 (2020).

Xue, T. et al. Southern Ocean phytoplankton under climate change: a shifting balance of bottom-up and top-down control. Biogeosciences 21, 2473–2491 (2024).

Thirumalai, K. et al. Future increase in extreme El Niño supported by past glacial changes. Nature 634, 374–380 (2024).

Hu, K., Huang, G., Huang, P., Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Intensification of El Niño-induced atmospheric anomalies under greenhouse warming. Nat. Geosci. 14, 377–382 (2021).

Tittensor, D. P. et al. Next-generation ensemble projections reveal higher climate risks for marine ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 973–981 (2021).

Huston, M. A. & Wolverton, S. The global distribution of net primary production: resolving the paradox. Ecol. Monogr. 79, 343–377 (2009).

Fernández-Martínez, M. et al. Diagnosing destabilization risk in global land carbon sinks. Nature 615, 848–853 (2023).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 1917–2005 (2022).

Kwiatkowski, L. et al. Emergent constraints on projections of declining primary production in the tropical oceans. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 355–358 (2017).

Zhao, Q., Zhu, Z., Zeng, H., Zhao, W. & Myneni, R. B. Future greening of the Earth may not be as large as previously predicted. Agric. Meteorol. 292, 108111 (2020).

Cao, D. et al. Projected increases in global terrestrial net primary productivity loss caused by drought under climate change. Earth’s Futur. 10, e2022EF002681 (2022).

Wieder, W. R., Cleveland, C. C., Smith, W. K. & Todd-Brown, K. Future productivity and carbon storage limited by terrestrial nutrient availability. Nat. Geosci. 8, 441–444 (2015).

Hou, H. et al. Future land use/land cover change has nontrivial and potentially dominant impact on global gross primary productivity. Earth’s Futur. 10, e2021EF002628 (2022).

Running, S. W. A measurable planetary boundary for the biosphere. Science 337, 1458–1459 (2012).

Richardson, K. et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh2458 (2023).

Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11645–11650 (2017).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Northrop, E. & Lubchenco, J. The ocean is key to achieving climate and societal goals. Science 365, 1372–1374 (2019).

Huang, X. et al. High spatial resolution vegetation gross primary production product: algorithm and validation. Sci. Remote Sens. 5, 100049 (2022).

Behrenfeld, M. J. & Falkowski, P. G. Photosynthetic rates derived from satellite‐based chlorophyll concentration. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42, 1–20 (1997).

EPPLEY, R. W. Temperature and phytoplankton growth in the sea. Fish. Bull. 70, 1063–1085 (1971).

Twedt, K., Xiong, X., Geng, X., Wilson, T. & Mu, Q. Impact of satellite orbit drift on MODIS Earth scene observations used in calibration of the reflective solar bands. In Proc. Earth Observing Systems XXVIII Vol. 12685, 158–167 (SPIE, 2023).

MODIS/Aqua ocean color reprocessing 2022.0. NASA https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/reprocessing/r2022/aqua/ (2025).

Sulla-Menashe, D., Gray, J. M., Abercrombie, S. P. & Friedl, M. A. Hierarchical mapping of annual global land cover 2001 to present: the MODIS Collection 6 Land Cover product. Remote Sens. Environ. 222, 183–194 (2019).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future Köppen–Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 5, 1–12 (2018).

Marine Ecoregions and Pelagic Provinces of the World. GIS Layers Developed by The Nature Conservancy with Multiple Partners, Combined from Spalding et al. (2007) and Spalding et al. (2012) (The Nature Conservancy, 2012).

Dang, X., Peng, H., Wang, X. & Zhang, H. Theil–Sen estimators in a multiple linear regression model. Olemiss Edu. 2, 1–30 (2008).

Tomé, A. R. & Miranda, P. M. A. Piecewise linear fitting and trend changing points of climate parameters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, 1–4 (2004).

pwlf: piecewise linear fitting https://jekel.me/piecewise_linear_fit_py (2025).

Bowen, N. K. & Guo, S. Structural Equation Modeling (ed. Brockveld, K. C.) Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Li, Z. & Cassar, N. A mechanistic model of an upper bound on oceanic carbon export as a function of mixed layer depth and temperature. Biogeosciences 14, 5015–5027 (2017).

Zhang, Y. & Cassar, N. Data and Python codes for ‘Contrasting biological production trends over land and ocean’. Open Science Framework https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/86K3N (2025).

Zhang, Y. Interactive tool for ‘Planetary Photosynthetic Productivity’. Google Earth Engine App https://planetlab.users.earthengine.app/view/p3npp (2025).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the NASA MODIS Ocean and Land Science Teams, M. Behrenfeld (Oregon State University), M. Zhao (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center), K. A. Endsley (University of Montana), S. Liang (University of Maryland), W. Ju (Nanjing University) and J. Chen (University of Toronto) for providing global ocean and land NPP products. We also thank the modelling groups contributing to CMIP6 for their ocean biogeochemistry simulations and the TRENDY project teams for their terrestrial biosphere model outputs, as coordinated through the Global Carbon Budget initiative. In addition, we extend our sincere appreciation to the institutions and researchers listed in Supplementary Table 1 for making the publicly available land and ocean datasets used in this study. Y.Z., W.L. and G.S. are partially supported by the Duke University–USDA Forest Service collaboration (grant no. 23-JV-11330180-119). N.C. is supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. OCE-2123198). J.X. is supported by the National Science Foundation (Macrosystem Biology and NEON-Enabled Science program: grant no. DEB-2017870). J.M. is supported by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) through the ‘Reducing Uncertainties in Biogeochemical Interactions through Synthesis and Computing’ scientific focus area and the ‘Terrestrial Ecosystem Science Scientific’ focus area, funded by the Earth and Environmental Systems Sciences Division of the Biological and Environmental Research Office within the US Department of Energy Office of Science. ORNL is managed by UT-Battelle, LLC, for the DOE under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and N.C. conceived the idea and designed the research. Y.Z., N.C., W.L., G.S., M.D., J.M., Z.L. and Q.Z. developed the methodology. Y.Z. and N.C. carried out the investigation. Y.Z. performed the data visualization and wrote the original draft of the paper. All authors, including Y.Z., N.C., W.L., G.S., J.M., M.D., J.X., Z.L., H.Z., Q.Z., S.H. and C.S., discussed the design, methods and results, and contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the paper

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Steven Running, Rui Sun and Toby Westberry for their contributions to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of global ensemble means and interannual variability in land and ocean NPP based on remote sensing products from 2003 to 2021.

a, Ensemble means of land NPP (N = 3), ocean NPP (N = 3) and global total NPP (N = 9). b, Annual land NPP changes from three RS-based products (BEPS, GLASS and MOD17). c, Annual ocean NPP changes from three RS-based products (CAFE, CbPM and EVGPM). In a, error bars represent the standard deviations across three models for both land and ocean NPP, as well as nine annual combinations for global NPP. Annual NPP anomalies in b and c are calculated relative to the multi-year mean (2003–2021) of each modeled NPP.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Annual ocean NPP changes along the latitudinal gradient (1° interval) from 2003 to 2021.

a, Annual NPP anomalies expressed as latitudinal area-weighted mean. b, Annual NPP anomalies expressed as latitudinal area-weighted total. In both panels, anomalies are calculated relative to the multiple year mean within each latitudinal band. The vertical line marks the 2015 breakpoint in the global ocean NPP trend, as shown in Fig. 1b. Two horizontal lines denote the mid- to high-latitude regions, where the decline-to-increase reversal in NPP is mainly observed.

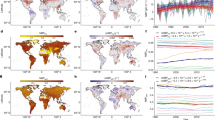

Extended Data Fig. 3 Evaluation of processed-based models in simulating land and ocean NPP with remote sensing (RS)-based models.

a, Annual land NPP from 16 Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs) and three RS-based models. b, Annual land NPP from the ensemble means of DGVM (DGVM-Mean) and RS-based models (RS-Mean), with shaded areas representing one standard deviation among each model group. c, Annual ocean NPP from 15 Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Models (GOBMs) and three RS-based models. d, Annual ocean NPP from the ensemble means of GOBMs (GOBM-Mean) and RS-based models (RS-Mean), with shaded areas representing one standard deviation among each model group. In a, b, DGVMs are from TRENDY V10 (2003 to 2020); In c, d, GOBMs are from historic simulations from CMIP6 (2003 to 2014).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Annual NPP trends and multi-year baseline NPP from 2003 to 2021 across land and ocean zones.

a, Land zones; b, Ocean zones. Land and ocean zones are shown in Extended Data Fig. 5. In b, cold oceans includes Southern Ocean and Arctic Oceans. Trends are calculated using Theil–Sen regression, with two-sided statistical significance assessed by the Mann–Kendall test (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Global zone classifications used in this study.

a, Land zones. b, Ocean zones. In a, terrestrial zones include TAM (Tropical America), TAF (Tropical Africa), TAS (Tropical Asia), AS (Arid/Semi-arid), TEM (Temperate), and BA (Boreal/Alpine). In b, marine zones include TPO (Tropical Pacific Ocean), NTP (Northern Temperate Pacific Ocean), STP (Southern Temperate Pacific Ocean), TAO (Tropical Atlantic Ocean), NTA (Northern Temperate Atlantic Ocean), STA (Southern Temperate Atlantic Ocean), TIO (Tropical Indian Ocean), STI (Southern Temperate Indian Ocean), AO (Arctic Ocean), SO (Southern Ocean), and SW (Shelf Water).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Co-regulation of gross primary production (GPP) and autotrophic respiration (AR) on annual NPP changes from 2003 to 2021.

a, Co-occurring trends of GPP and AR and their associations with NPP trends. Change classes are based on annual Theil-Sen’s slope: + (slope > 0), – (slope < 0). For example, GPP + AR + NPP+ indicates that positive trends in both GPP and AR are associated with an increase in NPP. b, Dominant drivers of NPP trends based on the relative magnitude of GPP and AR slopes. For instance, AR+ indicates that the absolute Theil-Sen’s slope of AR exceeds that of GPP, suggesting AR as the dominant influence on NPP. In a and b, values in parentheses represent the percentage of area relative to the global total vegetated land surface. c, Annual trends of key climate variables over tropical regions, including photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), precipitation, air temperature (TA), and vapor pressure deficit (VPD). d, Rank correlations among TA, VPD, GPP, and NPP across the tropical region.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Comparison of inter-annual variations in land and ocean NPP across different zones.

a. Land zones. b, Ocean zones. Annual NPP anomalies are relative to the multi-year mean from 2003 to 2021. Annual NPP values are detrended, and anomalies are calculated relative to the 2003–2021 mean for each zone. The zone exhibiting the highest absolute anomaly each year is marked with green circles for land NPP (in a) and purple circles for ocean NPP (in b). Zonal NPP values with Z-scores (defined as the ratio of the annual anomaly to the multi-year standard deviation) greater than 1.0 are indicated with an asterisk (*). Land and ocean zones are shown in Extended Data Fig. 5.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Environmental responses during the identified strong El Niño and La Niña events.

a, c, El Niño. b, d, La Niña. In a and b, land temperature represents the multi-year mean air temperature (TA), while ocean temperature refers to the multi-year mean sea surface temperature (SST) during the identified ENSO years. In c and d, land is represented by multi-year mean precipitation (PRE), and ocean is represented by multi-year mean mixed layer depth (MLD) during the identified ENSO years. All data are normalized as Z-scores, calculated by dividing annual anomalies by the multi-year standard deviation (2003–2021).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–4 and Table 1.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Li, W., Sun, G. et al. Contrasting biological production trends over land and ocean. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 880–888 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02375-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02375-1