Abstract

The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) has served as a key index linking basin-scale climate variability to marine ecosystem changes in the North Pacific. However, recent apparent breakdowns of PDO–ecosystem correlations have raised concerns about the stability of the mode and its continued relevance in a warming climate. Here we show that basin-wide warming now overwhelms PDO-related sea surface temperature (SST) variability, although neither the PDO’s spatial pattern nor its strength have changed. We introduce the pan-basin pattern as a complementary index to describe the non-stationary SST baseline of the North Pacific. Regional SSTs increasingly reflect the superposition of these two signals, providing an explanation for weakened or inverted PDO–ecosystem correlations. Future use of the PDO index in management will require discerning the effects of internal dynamics from those of absolute changes in SST as extreme and no-analogue ocean conditions driven by interacting natural variability and anthropogenic warming become more common.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

North Pacific climate variability has historically been dominated by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), an empirical mode describing concomitant warm sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the eastern Pacific and cold SST anomalies in the central and western Pacific during its positive ‘warm’ phase1,2,3,4. Associated with basin-scale atmospheric, oceanographic and ecological changes2,4,5,6, the PDO index is a popular indicator in marine resource management7,8, with its historical sign reversals (for example, 1925, 1947 and 1977) heralded as regime shifts—climate-driven reconfigurations of species distributions and abundances with major socioeconomic impacts2,5,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

In 1977, an abrupt shift of the PDO into its positive phase triggered pronounced responses in salmon fisheries along the North American west coast: catches surged in the Gulf of Alaska (GOA) but declined in the northern California Current13,16,17. These synchronous changes, coinciding with shifts in SST and other physical and ecological variables, drew attention to the underlying pattern of low-frequency climate variability and ultimately led to the identification and formalization of the PDO2,3,9. Although initially defined in the context of its influence on northeastern Pacific salmon, the PDO index has since emerged as a significant correlate in population and community dynamics across trophic levels, including species ranging from phytoplankton to seabirds and marine mammals throughout the North Pacific18,19,20,21,22,23,24.

In the past decade, previously quantified PDO–ecosystem relationships have been called into question25,26, prompting re-evaluations of the PDO’s regional impacts25,27,28,29 and claims that the mode itself fundamentally changed30. In the GOA, annual catches of salmon correlated negatively with the PDO from 2014–2019, a surprising departure from the significant positive correlation exhibited in previous decades2,13,27. Weakened responses to the PDO have been additionally documented among aggregated biological time series that include seabirds and ichthyoplankton in the California Current and groundfish, forage fish and crustaceans in the GOA29.

In this Article, we show that although the PDO has not changed in pattern or strength, pan-basin warming now overwhelms its SST changes, producing periods during which regional SST anomalies diverge from what is expected of the PDO’s expression. We introduce the pan-basin pattern (PBP) as a new index describing this basin-wide warming, and discuss how interacting PDO and PBP variability can produce diverse biological responses, including those observed in GOA salmon catches. Updating understanding of these patterns of North Pacific climate and their respective impacts is critical to ensure appropriate use of environmental indices in management. Furthermore, this work emphasizes the role of interacting internal variability and anthropogenic warming to produce no-analogue ocean regimes including the persistent extreme warm conditions of the past decade.

Emergent dominance of pan-basin warming

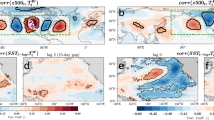

The PDO is defined as the leading empirical orthogonal function (EOF) of SST anomalies in the North Pacific (20–65° N, 105–260° E), canonically following removal of the global mean SST (GMSST) signal2,3. By this construction, the PDO is designed to describe internal climate variability distinct from global-scale temperature changes. This canonical PDO variability has been stable through recent decades, as represented in the leading EOF of GMSST-removed SST anomalies among sliding retrospective 30-year windows (Fig. 1, right column). Similarly, second EOFs consistently resemble the SST footprint of the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation (NPGO)/Victoria Mode pattern31,32. Both patterns exhibit only minor deviations in spatial pattern and explain stable amounts of variance through time (EOF1: 20–26%; EOF2: 12–16%; Fig. 2, bottom row). Before 2014, removal of the GMSST signal before calculation of the leading EOFs is trivial—the PDO patterns represented by EOF1 calculated with and without removal of the GMSST are strongly correlated (R = 0.98–0.99; Extended Data Fig. 1 and Fig. 1) and differences in the explained variance are negligible (Fig. 2).

Top: EOFs for total SST anomalies. Bottom: EOFs for GMSST-removed SST anomalies. The red dashed lines indicate the approximate year of transition from the PDO to the PBP in EOF1 calculated from total SST anomalies. The modes associated with each EOF are labelled, as visually identified in Fig. 1.

When including years beyond 2013, we observe a departure from the historical norm; the PDO is replaced by a new basin-wide pattern in the leading EOF of the total SST anomalies (that is, GMSST not removed). By the 30-year period ending in 2017, the first EOF is unidirectional across the entire North Pacific basin, with all loadings of the same sign (Fig. 1). We refer to this pattern (that is, EOF1 of the total SST anomalies for 1994–2023) as the PBP. As the magnitude of the PBP supersedes that of the PDO, the percentage variance explained by EOF1 increases (21–51%) to exceed any historical 30-year interval of the PDO (Fig. 2). The transition from PDO dominance to PBP dominance is robust to the inclusion of only winter months (November to March; Extended Data Fig. 2) and to changes in the length of the sliding window on which the EOFs are calculated, occurring within the past decade when considering sliding windows of 20–100 years (Extended Data Figs. 3–5). The resulting PBP index (that is, principal component 1 of the total SST anomalies for 1994–2023) exhibits a linear correlation of 0.80 to GMSST time series (Extended Data Figs. 6 and 7).

Robust PDO despite predominant warming

Although recently overshadowed by PBP warming, the PDO has neither changed in spatial pattern (Fig. 1) nor weakened relative to its historical expression (Fig. 2). For the 1994–2023 period, the SST pattern of the PDO occurs in the second EOF of total SST anomalies, tightly correlated with its representation in the first EOF of GMSST-removed SST anomalies (R = 0.99; Extended Data Fig. 1). Eigenvalues for this most recent (1994–2023) EOF1 of GMSST-removed SST anomalies and EOF2 of total SST anomalies are similar (0.12 versus 0.13) and within the historical range of GMSST-removed EOF1 values (0.095–0.170; Extended Data Fig. 8), and the resultant principal components are strongly correlated (Extended Data Figs. 6 and 7). However, the percentage variance of the PDO pattern in EOF2 of total SST anomalies decreases from 23 to 13% over the most recent decade, coincident with the overwhelming and increasing importance of the PBP in EOF1 (Fig. 2). Synchronous with the emergence of the PBP in EOF1, the PDO first appears in EOF2 of total SST anomalies in the 30-year period ending in 2015 (Fig. 1). The simultaneous change from the PBP to the first EOF and from the PDO to the second EOF underscores that these are two distinct patterns; the PDO emerges as both the leading mode of GMSST-removed SST anomalies and a secondary mode orthogonal to the PBP. Similarly, the historical EOF2 NPGO/Victoria Mode pattern is demoted to the third EOF of total SST anomalies for the 1994–2023 period, but explains a similar amount of absolute variance as in previous periods or with GMSST removed (Extended Data Fig. 9). These results indicate that although the dominant mode of total North Pacific SST change is now secular warming, the PDO and NPGO/Victoria Mode remain the leading internal climate modes.

Revisiting North Pacific climate changes

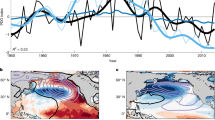

Projection of the most recent GMSST-removed EOF1 onto the full Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature (ERSST) dataset (1854–2024) reproduces the reversals of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Center for Environmental Information PDO index (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/pdo/; Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 6), showing the negative cold regimes of 1890–1924 and 1947–1976 and positive warm regimes of 1925–1946 and 1977 to the late 1990s. Since 2000, sub-decadal reversals occurred around 2003, 2006, 2014 and 2020. Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the PBP has increased along with the GMSST (Fig. 3a,b). The PDO probably plays some role in modulating global mean temperature, with previous negative PDO phases implicated in a hiatus in global mean surface temperature change through an increase in the heat content sequestered in the ocean subsurface in the tropics33,34,35,36. The apparent stepwise increase of the PBP coinciding with the transition into the positive PDO phase around 2014 could reflect such suppression and then rebound of the GMSST trend and/or the influence of reduced aerosol forcing in the western Pacific37.

a, GMSST anomalies. b, Principal component (PC) time series for PBP, defined as the leading EOF of total SST anomalies for 1994–2023 projected onto the full ERSST record. c, PDO time series as reconstructed from the leading EOF of GMSST-removed SST anomalies for 1994–2023 projected onto the full ERSST record. d–g, Predicted SST anomaly signals associated with the PBP (yellow) and PDO (red and blue) compared with the total SST anomalies (solid black lines) and PBP + PDO SST anomalies (dashed black lines) in the GOA (d), California Current (CC; e), Oyashio Current (OC; f) and Kuroshio Current (KC; g) LMEs, all shown as the three-month rolling mean. h, Map of the locations of the four LMEs shown in d–g.

PDO-related SST anomalies are notably stronger in the eastern Pacific than in the western Pacific, whereas PBP-related anomalies are more uniform (Fig. 3d–g). Although we do not expect the SST anomalies associated with the two modes to perfectly sum to the total SST anomalies (Fig. 3d–g, solid versus dashed lines), the first two EOFs explain more than 60% of the total variance in the most recent 30 years and indeed capture much of the total variability. In the northeast Pacific’s California Current and GOA large marine ecosystems (LMEs) (Fig. 3h), historical SST anomalies before 2014 largely tracked the PDO component, consistent with strong PDO loading in these regions. Historical SST anomalies in the Kuroshio Current and Oyashio Current LMEs more closely follow the PBP anomalies, consistent with the relatively strong PBP loadings and weak PDO loadings across these regions.

Crossplots of PDO- and PBP-related SST anomalies provide a framework for interpreting historical changes in the relative strength of regional expressions of global change (PBP) and internal variability (PDO) (Fig. 4a). Before 2014, variability in the northeast Pacific (GOA and California Current) concentrated along the PDO axis, consistent with the historical dominance of the PDO in these regions (Fig. 4b,c). From 2014–2016, strong PDO-positive and PBP-warming anomalies of comparable magnitude combined to produce exceptionally warm and persistent SST anomalies in the northeast Pacific, with notable marine heatwaves of 2014–2016 (the Blob) and 2019–2020 occurring when the PBP and PDO had constructive signals38,39,40,41,42,43. As the PDO became less positive from 2017–2020, PBP warming remained elevated; although the PBP signal dominated, positive SST anomalies in the eastern Pacific were still concordant with a positive PDO. However, when the PDO shifted into its negative phase around 2021, its associated northeast Pacific cooling was insufficient to offset the continued PBP warmth. Consequently, 2021–2024 represents the first sustained period of the recent historical record during which warming confounded PDO variability such that a negative ‘cold’ PDO phase did not coincide with negative SST anomalies in the eastern Pacific (Figs. 3d,e and 4b,c). In the western Pacific Kuroshio Current and Oyashio Current LMEs, where PDO loadings are historically weaker and more variable (Fig. 1), disagreement in the sign of the PDO and regional SST anomalies occurred around 2014–2019 during the previous negative PDO phase (Fig. 3f,g and Fig. 4d,e). In all four regions, the span of PDO SST anomaly variability is maintained while moving along the axis of global change, illustrating the superposition of internal variability on a shifting baseline.

a, Schematic for the interpretation of changes in SST related to internal variability (that is, the PDO; y axis) and global temperature change (that is, the PBP; x axis). In the top right and lower left quadrants PDO and PBP anomalies of the same direction yield constructive SST anomaly signals, whereas in the top left and lower right quadrants PDO and PBP anomalies of opposite signs are destructive. When the magnitude of the PDO-derived SST anomalies is greater than the absolute PBP-derived anomaly, internal variability dominates, whereas when the PBP SST is greater, global change overpowers the PDO. Years that fall within the hourglass are dominated by PDO variability, whereas years that fall within the bowtie are dominated by PBP change. b–d, As in a, predicted annual average SST anomalies in association with the PBP and PDO in LMEs of the North Pacific: GOA (b), CC (c), OC (d) and KC (e). Years are labelled for 2014–2023 only. The data point fill colours correspond to observed annual SST anomalies.

Non-stationary ecological responses to PDO variability

Although numerous studies document strong historical correlations between North Pacific ecosystem components and the PDO2,5,13,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, observations suggest that some of these relationships have weakened or even reversed in recent years25,27,29. We revisit the seminal case study of salmon variability in the GOA to examine how the superposition of PDO variability and PBP warming can obscure ecosystem impacts2,13,16,17,44. From 1965–1988, annual catches of pink, sockeye and coho salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha, O. nerka and O. kitsutch, respectively) showed strong positive correlations with the PDO index2,13,27. These correlations decayed from 1989–2013, then became significantly negative after 2014 (refs. 27,29), synchronous with the rising predominance of the PBP.

We can hypothesize a cause for these changing correlations by building a simple conceptual model assuming that a theoretical biological response (for example, salmon abundance) can be described as a function of temperature with a normal distribution centred on the thermal optimum (Fig. 5)45,46. Because the magnitude of PDO-related SST anomalies remains consistent under PBP warming (Figs. 2 and 4), the absolute SST associated with a given PDO index value shifts with the warming baseline, moving along the response curve as secular warming progresses. Positive correlations between pre-1989 salmon catches in the GOA and the PDO index suggest that historical PDO-related SST variability spanned the ascending arm of the theoretical response curve (Fig. 5; scenario A). As PBP warming raises absolute SSTs associated with PDO variability, SSTs during positive PDO phases begin to exceed the thermal optimum, triggering negative biological responses and decorrelation with the PDO index during the 1989–2013 period (Fig. 5; scenario B). Once the PBP baseline exceeds the thermal optimum, PDO-related variability falls on the descending arm of the response curve, aligning with the shift to negative correlations after 2014 (Fig. 5; scenario C). This model may also explain the weakening of already negative PDO correlations; as PBP warming pushes PDO variability further down the descending arm of the response curve to where it flattens, the biological response to warming during positive PDO phases is reduced.

This model assumes that a theoretical biological response (for example, salmon abundance) is described by a normal distribution as a function of SST, and that the range of SST anomalies variability associated with the PDO is maintained but shifted in absolute SST with PBP warming. In scenario A, the response positively correlates with the PDO index, as increasing PDO index values correspond to stronger biological responses, consistent with observed salmon catches in the GOA before 1989. In scenario B, with basin-wide warming, PDO variability shifts along the biological response curve towards the thermal optimum, resulting in decorrelation between the PDO index and biological response, as observed for GOA salmon catches from 1989–2013. In scenario C, as warming continues, PDO variability is shifted beyond the thermal optimum, resulting in negative correlations with the PDO index, as is seen for GOA salmon catches from 2014–2019. m is the slope of the linear correlation between PDO index values and the biological response. Salmon image from PhyloPic under a Creative Commons license PDM 1.0.

The application of this conceptual model to different species and populations will produce different outcomes based on how the species-specific thermal optima align with regional expressions of PBP and PDO variability (for example, Figs. 3 and 4). For example, catches of salmon in the northern California Current (Washington, Oregon and California, near the species’ southern range) were historically negatively associated with the PDO index, albeit more weakly correlated with the PDO index than the GOA salmon catches2,13. Warmer SSTs in the south would place the salmon catches further along the response curve, which may explain the divergent historical responses to the PDO between the two regions. Critically, this conceptual model assumes that absolute SSTs primarily drive biological impacts. For biological responses to the PDO that are driven by variability associated with other aspects of the PDO, such as changes in upwelling or thermocline depth, the PDO–biology correlations may be unchanged or exhibit more complicated responses. Thus, this model offers a conceptual framework for understanding the diversity of biological responses to the PDO under PBP warming, including the weakening, strengthening, inversion or perpetuation of historical correlations. Further research is needed to explore whether incorporating both the PDO and PBP may recover some of the biological inferences lost since 2014.

Discussion

We demonstrate that the leading mode of interdecadal North Pacific SST changes recently transitioned from the PDO to a pattern of unidirectional change across the entire basin (that is, the PBP). For the first prolonged period of the recent observational record, a negative ‘cold’ PDO phase failed to coincide with cool SST anomalies in the eastern Pacific—a harbinger of the increasing non-stationarity in relationships between the PDO and regional SSTs (Fig. 3d,e). Despite explaining proportionally less variance, ongoing robust PDO variability indicates that drivers of the mode’s SST anomaly footprint have been resilient to warming through the early twenty-first century (Figs. 1 and 2). As the PDO is a statistically emergent pattern integrating several processes (for example, stochastic Aleutian Low forcing, teleconnections with the tropics, and ocean Rossby waves)4,47, its future evolution will depend on how these contributing processes are cumulatively impacted by warming across timescales.

Although the historical physical drivers of North Pacific decadal variability are relatively well understood4,48, the biophysical mechanisms through which ecosystems respond are less so. The PDO has historically served as a reliable proxy for SST in much of the North Pacific. However, as regional SST anomalies continue to diverge from those historically expected based on PDO signals (Fig. 3d–g), there will be a growing need to distinguish impacts associated solely with SST anomalies from those produced by the dynamics related to the PDO (for example, changes in upwelling, transport or source waters). For example, since the 2021 transition into the negative PDO phase (Figs. 3d,e and 4b,c), warming is superimposed on a cold PDO regime in the eastern North Pacific, leading to confusion in the community regarding the expected biological effects26. Further investigation into the mechanisms behind PDO–ecosystem relationships should prioritize discernment of temperature-specific effects on biology from the effects of other physical or biogeochemical processes. Given the ongoing stability of the PDO pattern, the PDO index probably remains a useful indicator of North Pacific climate variability, but perhaps with its ecological relevance in how it reflects changing dynamical processes rather than regional SST anomalies.

As the PBP–temperature baseline climbs in concert with global ocean warming, local and regional SST anomalies that would historically have been associated with an exceptionally strong PDO and/or El Niño (for example, >2 standard deviations) will occur more frequently. For example, constructive signals between internal variability and secular warming from 2014–2020 contributed to warm temperature extremes during this period (for example, ref. 49). Quantification of the range of internal variability related to the PDO and other modes will be needed to constrain the potential for climate extremes resulting from interaction of internal variability and anthropogenic warming, leveraging approaches such as palaeoclimate records, long model simulations or large model ensembles50,51. Constraining internal variability and stability is also necessary for understanding the future of PDO impacts beyond the North Pacific (for example, theorized impacts on hydroclimate in western North America and northeastern Asia)52,53,54,55,56,57 and its role in modulating global climate.

Global-scale trends and internal variability are now both important determinants of North Pacific climate48,58, with the influence of pan-basin warming surpassing that of the PDO within the past decade. The combination of long-term warming and natural variability has already begun to produce profound physical and ecological changes throughout the North Pacific, including severe marine heatwaves with ecosystem-wide impacts59,60, rapid sea ice declines and novel weather patterns in the Alaskan Arctic61, and new human–wildlife conflicts62. Management decisions based on historical baselines will fail to capture increasingly important emergent interactions between anthropogenic warming and internal variability. This increased uncertainty in associations between basin-scale variability and regional responses underscores the need for management approaches to incorporate dynamical modelling and prediction of North Pacific climate (for example, ref. 63), rather than relying on historical relationships with basin-scale indicators as predictors. Given that the internal variability of the North Pacific is especially strong, a similar emergence of pan-basin warming over internal variability is probably already occurring in other basins, suggesting that the recontextualization of indices of climate variability under warming is needed widely.

Methods

We analysed historical SSTs provided by version 5 of the NOAA ERSST (ERSSTv5) at 2°-latitude by 2°-longitude resolution monthly from January 1854 to the present (retrieved February 2024)64. The ERSST was developed, in part, through the use of EOFs to reconstruct spatial SST fields, but robustly describes long-term trends and patterns of variability in the North Pacific throughout the twentieth century65. Moreover, we focused our analysis on the post-1960 period for which spatially comprehensive observations are available.

We first quantified the leading modes of variability of North Pacific SST anomalies through the past century and examined how these modes differ when calculated with the GMSST signal removed (that is, the canonical PDO calculation3) or not (that is, calculated based on the total SST anomalies). To this end, we calculated EOFs of North Pacific SST anomalies for 105° E–80° W and 20–65° N in 30-year intervals with and without subtraction of the GMSST anomaly. All EOFs were computed using the Jacobi method for singular value decomposition with area weights, using Climate Data Operators66. We calculated all EOFs using monthly SST anomalies relative to the 1854–2024 climatology; because we were targeting the evolution of interannual–interdecadal variability relative to the shifting baseline associated with global temperature change, the choice to centre EOFs on the extended climatology was appropriate here (for example, as in ref. 30). We analysed patterns of SST variability in 30-year windows, which were long enough to capture decadal-scale variations but frequent enough to enable the detection of changes in these patterns with some precision.

We projected the leading EOFs in the most recent 30-year interval (1994–2023), calculated with and without removal of GMSST, onto the full SST anomaly record to produce principal component time series extending back to 1854. The principal component scores were normalized to the standard deviation of the full record (1854–2024). We calculated expected contributions of each pattern to SST anomalies by regressing the principal components on monthly SST anomalies to calculate linear principal component–SST anomaly transfer functions for each grid cell. We then predicted SST anomalies along each principal component time series to generate fields of the SST anomalies expected in association with each mode in each time step, and calculated the mean predicted SST anomalies for each of several LMEs of the North Pacific: the GOA, California Current, Kuroshio Current and Oyashio Current (Fig. 3h). Code for the analysis described above is publicly archived67.

Data availability

All analyses were conducted on the freely accessible NOAA ERSSTv5, which is hosted by the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html). PBP index values are included in Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

The code used to calculate and visualize the results is publicly available from GitHub (https://github.com/acluett/PBP-PDO-Indices) and archived on FigShare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30261070)67.

References

MacDonald, G. M. & Case, R. A. Variations in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation over the past millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L08703 (2005).

Mantua, N. J., Hare, S. R., Zhang, Y., Wallace, J. M. & Francis, R. C. A Pacific Interdecadal Climate Oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 78, 1069–1080 (1997).

Mantua, N. J. & Hare, S. R. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation. J. Oceanogr. 58, 35–44 (2002).

Newman, M. et al. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation, revisited. J. Clim. 29, 4399–4427 (2016).

Chavez, F. P., Ryan, J., Lluch-Cota, S. E. & Ñiquen C, M. From anchovies to sardines and back: multidecadal change in the Pacific Ocean. Science 299, 217–221 (2003).

Zhang, Y., Wallace, J. M. & Battisti, D. S. ENSO-like interdecadal variability: 1900–93. J. Clim. 10, 1004–1020 (1997).

Litzow, M. A. & Mueter, F. J. Assessing the ecological importance of climate regime shifts: an approach from the North Pacific Ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 120, 110–119 (2014).

Peterson, W. T. et al. Applied fisheries oceanography: ecosystem indicators of ocean conditions inform fisheries management in the California current. Oceanography 27, 80–89 (2014).

Ebbesmeyer, C. C. et al. 1976 step in the Pacific climate: forty environmental changes between 1968–1975 and 1977–1984. In Proc. 7th Annual Climate Workshop 115–126 (California Department of Water Resources, 1990).

Miller, A. J., Cayan, D. R., Barnett, T. P., Graham, N. E. & Oberhuber, J. M. Interdecadal variability of the Pacific Ocean: model response to observed heat flux and wind stress anomalies. Clim. Dyn. 9, 287–302 (1994).

Beamish, R. J., Benson, A. J., Sweeting, R. M. & Neville, C. M. Regimes and the history of the major fisheries off Canada’s west coast. Prog. Oceanogr. 60, 355–385 (2004).

Peterson, W. T. & Schwing, F. B. A new climate regime in northeast Pacific ecosystems. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2003GL017528 (2003).

Hare, S. R., Mantua, N. J. & Francis, R. C. Inverse production regimes: Alaska and West Coast Pacific salmon. Fisheries 24, 6–14 (1999).

Santora, J. A. et al. Impacts of ocean climate variability on biodiversity of pelagic forage species in an upwelling ecosystem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 580, 205–220 (2017).

Schroeder, I. D. et al. Source water variability as a driver of rockfish recruitment in the California Current Ecosystem: implications for climate change and fisheries management. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 76, 950–960 (2019).

Francis, R. C. & Hare, S. R. Decadal-scale regime shifts in the large marine ecosystems of the North-East Pacific: a case for historical science. Fish. Oceanogr. 3, 279–291 (1994).

Hare, S. R. & Francis, R. C. Climate change and salmon production in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. In Climate Change and Northern Fish Populations (ed. Beamish, R. J.) 357–372 (NRC Research Press, 1995).

Chiba, S., Batten, S., Sasaoka, K., Sasai, Y. & Sugisaki, H. Influence of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation on phytoplankton phenology and community structure in the western North Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 2012GL052912 (2012).

Hipfner, J. M., Galbraith, M., Bertram, D. F. & Green, D. J. Basin-scale oceanographic processes, zooplankton community structure, and diet and reproduction of a sentinel North Pacific seabird over a 22-year period. Prog. Oceanogr. 182, 102290 (2020).

Biela, V. R. et al. Influence of basin- and local-scale environmental conditions on nearshore production in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Mar. Coast. Fish. 8, 502–521 (2016).

Vandenbosch, R. Effects of ENSO and PDO events on seabird populations as revealed by Christmas bird count data. Waterbirds 23, 416–422 (2000).

Champagnon, J., Lebreton, J.-D., Drummond, H. & Anderson, D. J. Pacific Decadal and El Niño oscillations shape survival of a seabird. Ecology 99, 1063–1072 (2018).

Perryman, W. L., Joyce, T., Weller, D. W. & Durban, J. W. Environmental factors influencing eastern North Pacific gray whale calf production 1994–2016. Mar. Mammal. Sci. 37, 448–462 (2021).

Ingman, K. et al. Modeling changes in baleen whale seasonal abundance, timing of migration, and environmental variables to explain the sudden rise in entanglements in California. PLoS ONE 16, e0248557 (2021).

Litzow, M. A. et al. Non-stationary climate–salmon relationships in the Gulf of Alaska. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20181855 (2018).

Thompson, A. R. et al. State of the California Current Ecosystem report in 2022: a tale of two La Niñas. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1294011 (2024).

Litzow, M. A. et al. Quantifying a novel climate through changes in PDO–climate and PDO–salmon relationships. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087972 (2020).

Zwolinski, J. P. & Demer, D. A. Re-evaluation of the environmental dependence of Pacific sardine recruitment. Fish. Res. 216, 120–125 (2019).

Litzow, M. A. et al. The changing physical and ecological meanings of North Pacific Ocean climate indices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 7665–7671 (2020).

Werb, B. E. & Rudnick, D. L. Remarkable changes in the dominant modes of North Pacific sea surface temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101078 (2023).

Bond, N. A., Overland, J. E., Spillane, M. & Stabeno, P. Recent shifts in the state of the North Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2003GL018597 (2003).

Di Lorenzo, E. et al. North Pacific Gyre Oscillation links ocean climate and ecosystem change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L08607 (2008).

Courtillot, V., Le Mouël, J.-L., Kossobokov, V., Gibert, D. & Lopes, F. Multi-decadal trends of global surface temperature: a broken line with alternating ∼30 yr linear segments? Atmos. Clim. Sci. 3, 364–371 (2013).

Medhaug, I., Stolpe, M. B., Fischer, E. M. & Knutti, R. Reconciling controversies about the ‘global warming hiatus’. Nature 545, 41–47 (2017).

Yao, S.-L., Luo, J.-J., Huang, G. & Wang, P. Distinct global warming rates tied to multiple ocean surface temperature changes. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 486–491 (2017).

Trenberth, K. E., Fasullo, J. T., Branstator, G. & Phillips, A. S. Seasonal aspects of the recent pause in surface warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 911–916 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Atmosphere teleconnections from abatement of China aerosol emissions exacerbate Northeast Pacific warm blob events. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2313797121 (2024).

Amaya, D. J., Miller, A. J., Xie, S.-P. & Kosaka, Y. Physical drivers of the summer 2019 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Commun. 11, 1903 (2020).

Capotondi, A., Newman, M., Xu, T. & Di Lorenzo, E. An optimal precursor of Northeast Pacific marine heatwaves and Central Pacific El Niño events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097350 (2022).

Dalsin, M., Walter, R. K. & Mazzini, P. L. F. Effects of basin-scale climate modes and upwelling on nearshore marine heatwaves and cold spells in the California Current. Sci. Rep. 13, 12389 (2023).

Di Lorenzo, E. & Mantua, N. Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1042–1047 (2016).

Overland, J. E., Wang, M. & Ballinger, T. J. Recent increased warming of the Alaskan marine Arctic due to midlatitude linkages. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 35, 75–84 (2018).

Ren, X., Liu, W., Capotondi, A., Amaya, D. J. & Holbrook, N. J. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation modulated marine heatwaves in the Northeast Pacific during past decades. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 218 (2023).

Beamish, R. J. et al. The regime concept and natural trends in the production of Pacific salmon. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56, 516–526 (1999).

Pauly, D. On the interrelationships between natural mortality, growth parameters, and mean environmental temperature in 175 fish stocks. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 39, 175–192 (1980).

Savage, V. M., Gillooly, J. F., Brown, J. H., West, G. B. & Charnov, E. L. Effects of body size and temperature on population growth. Am. Nat. 163, 429–441 (2004).

Schneider, N. & Cornuelle, B. D. The forcing of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. J. Clim. 18, 4355–4373 (2005).

Di Lorenzo, E. et al. Modes and mechanisms of Pacific Decadal-scale variability. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 249–275 (2023).

Jacox, M. G., Alexander, M. A., Stock, C. A. & Hervieux, G. On the skill of seasonal sea surface temperature forecasts in the California Current System and its connection to ENSO variability. Clim. Dyn. 53, 7519–7533 (2017).

Deser, C. et al. Future changes in the intensity and duration of marine heat and cold waves: insights from coupled model initial-condition large ensembles. J. Clim. 37, 1877–1902 (2024).

Gedalof, Z., Mantua, N. J. & Peterson, D. L. A multi-century perspective of variability in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation: new insights from tree rings and coral. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 57-1–57-4 (2002).

Chan, J. C. L. & Zhou, W. PDO, ENSO and the early summer monsoon rainfall over south China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L08810 (2005).

Chen, W., Feng, J. & Wu, R. Roles of ENSO and PDO in the link of the East Asian winter monsoon to the following summer monsoon. J. Clim. 26, 622–635 (2013).

Hu, Z.-Z. & Huang, B. Interferential impact of ENSO and PDO on dry and wet conditions in the U.S. Great Plains. J. Clim. 22, 6047–6065 (2009).

McCabe, G. J., Palecki, M. A. & Betancourt, J. L. Pacific and Atlantic Ocean influences on multidecadal drought frequency in the United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4136–4141 (2004).

Ryzhkova, N. et al. PDO dynamics shape the fire regime of boreal subarctic landscapes in the Northwest Territories, Canada. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 130, e2024JG008178 (2025).

Fang, K. et al. Hydroclimate variations in central and monsoonal Asia over the past 700 years. PLoS ONE 9, e102751 (2014).

Overland, J. E. & Wang, M. Future climate of the north Pacific Ocean. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 88, 178–182 (2007).

Cavole, L. M. et al. Biological impacts of the 2013–2015 warm-water anomaly in the Northeast Pacific: winners, losers, and the future. Oceanography 29, 273–285 (2016).

Suryan, R. M. et al. Ecosystem response persists after a prolonged marine heatwave. Sci. Rep. 11, 6235 (2021).

Ballinger, T. J. & Overland, J. E. The Alaskan Arctic regime shift since 2017: a harbinger of years to come? Polar Sci. 32, 100841 (2022).

Santora, J. A. et al. Habitat compression and ecosystem shifts as potential links between marine heatwave and record whale entanglements. Nat. Commun. 11, 536 (2020).

Tommasi, D. et al. Managing living marine resources in a dynamic environment: the role of seasonal to decadal climate forecasts. Prog. Oceanogr. 152, 15–49 (2017).

Huang, B. et al. Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Wen, C., Kumar, A. & Xue, Y. Factors contributing to uncertainty in Pacific Decadal Oscillation index. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 7980–7986 (2014).

Schulzweida, U. CDO User Guide. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10020800 (2023).

Cluett, A. et al. Supplementary code for: Pan-basin warming now overshadows robust Pacific Decadal Oscillation. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30261070 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NOAA’s Changing Ecosystem and Fisheries Initiative, Integrated Ecosystem Assessment Program and Modeling, Analysis, Predictions, and Projections Program. We thank N. Mantua for providing helpful feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.C. conceptualized and performed the analyses and prepared the paper. S.J.B., M.G.J., M.P.B. and E.L.H. contributed to interpretation of the analyses and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Xianyao Chen, Yanyan Huang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Correlations between North Pacific sliding EOFs and the PDO.

A) Pattern correlation coefficients (area weighted) between the total SSTa EOF 1 and GMSST-removed EOF 1 (black points) and between the total SST anomaly EOF 2 and GMSST-removed EOF 1 (white points), for 30-year sliding windows (end-year indicated by each data point) as shown in Fig. 1. B) Principal component correlation coefficients between the total SST anomaly PC 1 and GMSST-removed PC 1 (black points) and between the total SSTa PC 2 and GMSST-removed PC 1 (white points), for 30-year sliding windows (end-year indicated by each data point) as shown in Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Sensitivity of emergent pan-basin warming to seasonality (winter).

As in Fig. 1, but calculated using winter season only (NDJFM).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Sensitivity of emergent pan-basin warming to timeframe (20 years).

As in Fig. 1, calculated with 20-year windows.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Sensitivity of emergent pan-basin warming to timeframe (50 years).

As in Fig. 1, calculated with 50-year windows.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Sensitivity of emergent pan-basin warming to timeframe (100 years).

As in Fig. 1, calculated with 100-year windows.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Global mean sea surface temperature and North Pacific index time series.

Time series of the A) GMSST anomaly, B) PDO and C) NPGO indices provided by the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory, and first and second principal component time series for the total SST anomaly (D-E) and GMSST-removed (F-G) EOFs for the 1994-2023 period.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Correlations between global mean sea surface temperature and North Pacific index time series.

Linear correlations between monthly principal component time series as shown in Extended Data Fig. 6 (EOFs calculated for the 1994-2023 period), GMSST, and the PDO index provided by the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory (PSL). Correlation coefficients are provided in the upper left corner of each panel.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Eigenvalues of North Pacific sliding EOFs.

As in Fig. 2, showing eigenvalues rather than percentage variance explained.

Extended Data Fig. 9 First three EOFs of North Pacific total and GMSST-removed SST anomaly, showing the PDO and NPGO patterns.

Leading EOFs of total (top row) and GMSST-removed (bottom row) SST anomaly for 1994-2023, showing the NPGO/Victoria Mode in EOF 3 and EOF 2, respectively.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

Monthly PBP values calculated as the leading EOF of North Pacific SST anomalies, without removal of the GMSST anomaly, based on NOAA’s ERSSTv5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cluett, A.A., Bograd, S.J., Jacox, M.G. et al. Pan-basin warming now overshadows robust Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 1340–1347 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02482-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02482-z