Abstract

Long-term, large-scale experimental studies provide critical information about how global change influences communities. When environmental changes are severe, they can trigger abrupt transitions from one community type to another leading to a regime shift. From 2014 to 2016, rocky intertidal habitats in the northeast Pacific Ocean experienced extreme temperatures during a multi-year marine heatwave (MHW) and sharp population declines of the keystone predator Pisaster ochraceus due to sea star wasting disease (SSWD). Here we measured the community structure before, during and after the MHW onset and SSWD outbreak in a 15-year succession experiment conducted in a rocky intertidal meta-ecosystem spanning 13 sites on four capes in Oregon and northern California, United States. Kelp abundance declined during the MHW due to extreme temperatures, while gooseneck barnacle and mussel abundances increased due to reduced predation pressure after the loss of Pisaster from SSWD. Using several methods, we detected regime shifts from substrate- or algae-dominated to invertebrate-dominated alternative states at two capes. After water temperatures cooled and Pisaster population densities recovered, community structure differed from pre-disturbance conditions, suggesting low resilience. Consequently, thermal stress and predator loss can result in regime shifts that fundamentally alter community structure even after restoration of baseline conditions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Community structure data are available on the Environmental Data Initiative Data Portal (https://doi.org/10.6073/pasta/1589a0ed9412db430a5555bc968a18a0). Temperature data (for example, https://doi.org/10.6085/AA/YBHX00_XXXITV2XMMR03_20200919.50.1) and sea star population data (https://doi.org/10.6085/AA/LTREB_Data.1.1) are published on DataONE. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code supporting the findings of this study is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/zechmeunier/intertidal-regime-shifts).

References

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1324 (2018).

McCabe, R. M. et al. An unprecedented coastwide toxic algal bloom linked to anomalous ocean conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 10,366–10,376 (2016).

Chan, F., Barth, J., Kroeker, K., Lubchenco, J. & Menge, B. The dynamics and impact of ocean acidification and hypoxia: insights from sustained investigations in the northern California current large marine ecosystem. Oceanography 32, 62–71 (2019).

Hughes, T. P. & Connell, J. H. Multiple stressors on coral reefs: a long-term perspective. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 932–940 (1999).

McCauley, D. J. et al. Marine defaunation: animal loss in the global ocean. Science 347, 1255641 (2015).

Scheffer, M. et al. Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature 461, 53–59 (2009).

Conversi, A. et al. A holistic view of marine regime shifts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20130279 (2015).

Rogers-Bennett, L. & Catton, C. A. Marine heat wave and multiple stressors tip bull kelp forest to sea urchin barrens. Sci. Rep. 9, 15050 (2019).

Ling, S. D. et al. Global regime shift dynamics of catastrophic sea urchin overgrazing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20130269 (2015).

Estes, J. A. & Palmisano, J. F. Sea otters: their role in structuring nearshore communities. Science 185, 1058–1060 (1974).

Watson, J. & Estes, J. A. Stability, resilience, and phase shifts in rocky subtidal communities along the west coast of Vancouver Island. Can. Ecol. Monogr. 81, 215–239 (2011).

Schultz, J. A., Cloutier, R. N. & Côté, I. M. Evidence for a trophic cascade on rocky reefs following sea star mass mortality in British Columbia. PeerJ 4, e1980 (2016).

Burt, J. M. et al. Sudden collapse of a mesopredator reveals its complementary role in mediating rocky reef regime shifts. Proc. R. Soc. B. 285, 20180553 (2018).

Harvell, C. D. et al. Disease epidemic and a marine heat wave are associated with the continental-scale collapse of a pivotal predator (Pycnopodia helianthoides). Sci. Adv. 5, eaau7042 (2019).

Bond, N. A., Cronin, M. F., Freeland, H. & Mantua, N. Causes and impacts of the 2014 warm anomaly in the NE Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 3414–3420 (2015).

Gentemann, C. L., Fewings, M. R. & García‐Reyes, M. Satellite sea surface temperatures along the West Coast of the United States during the 2014–2016 northeast Pacific marine heat wave. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 312–319 (2017).

Hobday, A. et al. Categorizing and naming marine heatwaves. Oceanography 31, 162–173 (2018).

Weitzman, B. et al. Changes in rocky intertidal community structure during a marine heatwave in the Northern Gulf of Alaska. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 556820 (2021).

Suryan, R. M. et al. Ecosystem response persists after a prolonged marine heatwave. Sci. Rep. 11, 6235 (2021).

Magel, C. L., Chan, F., Hessing-Lewis, M. & Hacker, S. D. Differential responses of eelgrass and macroalgae in Pacific Northwest estuaries following an unprecedented NE Pacific Ocean marine heatwave. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 16 (2022).

Spiecker, B. J. & Menge, B. A. El Niño and marine heatwaves: ecological impacts on Oregon rocky intertidal kelp communities at local to regional scales. Ecol. Monogr. 92, e1504 (2022).

Whalen, M. A., Starko, S., Lindstrom, S. C. & Martone, P. T. Heatwave restructures marine intertidal communities across a stress gradient. Ecology 104, e4027 (2023).

Cavole, L. et al. Biological Impacts of the 2013–2015 warm-water anomaly in the Northeast Pacific: winners, losers, and the future. Oceanography 29, 273–285 (2016).

Miner, C. M. et al. Large-scale impacts of sea star wasting disease (SSWD) on intertidal sea stars and implications for recovery. PLoS ONE 13, e0192870 (2018).

Menge, B. A. et al. Sea star wasting disease in the keystone predator Pisaster ochraceus in Oregon: insights into differential population impacts, recovery, predation rate, and temperature effects from long-term research. PLoS ONE 11, e0153994 (2016).

Konar, B. et al. Wasting disease and static environmental variables drive sea star assemblages in the Northern Gulf of Alaska. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 520, 151209 (2019).

Paine, R. T. Food web complexity and species diversity. Am. Nat. 100, 65–75 (1966).

Menge, B. A. et al. Keystone predation: trait‐based or driven by extrinsic processes? Assessment using a comparative-experimental approach. Ecol. Monogr. 91, e01436 (2021).

Paine, R. T. Size-limited predation: an observational and experimental approach with the Mytilus–Pisaster interaction. Ecology 57, 858–873 (1976).

Moritsch, M. M. Expansion of intertidal mussel beds following disease-driven reduction of a keystone predator. Mar. Environ. Res. 169, 105363 (2021).

Hacker, S. D., Menge, B. A., Nielsen, K. J., Chan, F. & Gouhier, T. C. Regional processes are stronger determinants of rocky intertidal community dynamics than local biotic interactions. Ecology 100, e02763 (2019).

Eisenlord, M. E. et al. Ochre star mortality during the 2014 wasting disease epizootic: role of population size structure and temperature. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150212 (2016).

Menge, B. A. et al. Stasis or kinesis? Hidden dynamics of a rocky intertidal macrophyte mosaic revealed by a spatially explicit approach. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 314, 3–39 (2005).

Menge, B. A., Gouhier, T. C., Hacker, S. D., Chan, F. & Nielsen, K. J. Are meta-ecosystems organized hierarchically? A model and test in rocky intertidal habitats. Ecol. Monogr. 85, 213–233 (2015).

Traiger, S. B. et al. Evidence of increased mussel abundance related to the Pacific marine heatwave and sea star wasting. Mar. Ecol. 43, e12715 (2022).

Menge, B. A., Gravem, S. A., Johnson, A., Robinson, J. W. & Poirson, B. N. Increasing instability of a rocky intertidal meta-ecosystem. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2114257119 (2022).

Sanford, E. D. & Menge, B. A. Reproductive output and consistency of source populations in the sea star Pisaster ochraceus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 349, 1–12 (2007).

Lüning, K. & Freshwater, W. Temperature tolerance of Northeast Pacific marine algae. J. Phycol. 24, 310–315 (1988).

Barner, A. K., Hacker, S. D., Menge, B. A. & Nielsen, K. J. The complex net effect of reciprocal interactions and recruitment facilitation maintains an intertidal kelp community. J. Ecol. 104, 33–43 (2016).

Paine, R. T. & Trimble, A. C. Abrupt community change on a rocky shore—biological mechanisms contributing to the potential formation of an alternative state. Ecol. Lett. 7, 441–445 (2004).

Beisner, B., Haydon, D. & Cuddington, K. Alternative stable states in ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 1, 376–382 (2003).

Benedetti-Cecchi, L., Tamburello, L., Maggi, E. & Bulleri, F. Experimental perturbations modify the performance of early warning indicators of regime shift. Curr. Biol. 25, 1867–1872 (2015).

Estes, J. A. et al. Trophic downgrading of Planet Earth. Science 333, 301–306 (2011).

Hobbs, R. J., Higgs, E. & Harris, J. A. Novel ecosystems: implications for conservation and restoration. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 599–605 (2009).

Menge, B. A. & Menge, D. N. L. Dynamics of coastal meta-ecosystems: the intermittent upwelling hypothesis and a test in rocky intertidal regions. Ecol. Monogr. 83, 283–310 (2013).

Jacox, M. G., Edwards, C. A., Hazen, E. L. & Bograd, S. J. Coastal upwelling revisited: Ekman, Bakun, and improved upwelling indices for the U.S. West Coast. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 7332–7350 (2018).

Schlegel R. W. & Smit A. J. heatwaveR: a central algorithm for the detection of heatwaves and cold-spells. R package version 0.4.6 (R Project, 2018).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Thomsen, M. S. et al. Local extinction of bull kelp (Durvillaea spp.) due to a marine heatwave. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 84 (2019).

Filbee-Dexter, K. et al. Marine heatwaves and the collapse of marginal North Atlantic kelp forests. Sci. Rep. 10, 13388 (2020).

Oksanen et al. vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.6-2 (R Project, 2022).

Maechler, M., Rousseeuw, P., Struyf, A., Hubert, M. & Hornik, K. cluster: cluster analysis basics and extensions. R package version 2.1.4 (R Project, 2022).

De Caceres, M. & Legendre, P. indicspecies: relationship between species and groups of sites. R package version 1.7.12 (R Project, 2022).

Smith, R. J. Solutions for loss of information in high-beta-diversity community data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 68–74 (2017).

Arribas, L. P., Donnarumma, L., Palomo, M. G. & Scrosati, R. A. Intertidal mussels as ecosystem engineers: their associated invertebrate biodiversity under contrasting wave exposures. Mar. Biodiv. 44, 203–211 (2014).

Elsberry, L. & Bracken, M. Functional redundancy buffers mobile invertebrates against the loss of foundation species on rocky shores. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 673, 43–54 (2021).

Legendre, P. in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity 264–268 (Elsevier, 2013).

McCune, B. & Grace, J. B. Analysis of Ecological Communities (MjM Software, 2002).

Holling, C. S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 1–23 (1973).

Aarts E. mHMMbayes: multilevel hidden Markov models using Bayesian estimation. R package version 0.2.0 (R Project, 2022).

Zucchini, W., MacDonald, I. L. & Langrock, R. Hidden Markov Models for Time Series: An Introduction Using R. (CRC Press, 2016).

McClintock, B. T. et al. Uncovering ecological state dynamics with hidden Markov models. Ecol. Lett. 23, 1878–1903 (2020).

Glennie, R. et al. Hidden Markov models: pitfalls and opportunities in ecology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 43–56 (2023).

Gal, G. & Anderson, W. A novel approach to detecting a regime shift in a lake ecosystem. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 45–52 (2010).

Gennaretti, F., Arseneault, D., Nicault, A., Perreault, L. & Bégin, Y. Volcano-induced regime shifts in millennial tree-ring chronologies from northeastern North America. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10077–10082 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Aerni, R. Askerooth, A. Barner, D. Chabot, A. Chiachi, M. Feezell, L. Field, H. Fulton-Bennett, S. Gerrity, T. Kruss, K. Matthews, B. Meunier, L. Miksell, S. Ngo, K. Nielsen, J. Robinson and E. Van Belle for field assistance. The raw temperature data were processed by M. Frenock and R. Gaddam. Most California measurements of Pisaster ochraceus size were provided by the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe), a long-term ecological consortium funded and supported by many groups. This work was supported by National Science Foundation grants to B.A.M., S.D.H. and colleagues. Z.D.M. received fellowship and grant support from the National Science Foundation, Oregon State University and the Phycological Society of America. This is contribution number 535 from PISCO (http://www.piscoweb.org/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D.H. and B.A.M. designed the study. All authors conducted the field experiment. Z.D.M. performed quality assurance on the datasets, analysed the data, created figures and tables and drafted the initial paper. All authors interpreted the results and revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Luca Rindi, J. Wootton and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

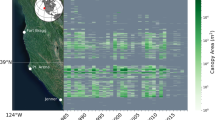

Extended Data Fig. 1 Experimental plots and locations of rocky intertidal sites on the coasts of Oregon and northern California.

Permanent plots (n = 260) were established in the low intertidal zone and assigned to control, recovery, macrophyte-only or invertebrate-only treatments in five replicate blocks per site. a, Replicate block showing control treatment (blue outline) and the recovery, macrophyte-only and invertebrate-only treatments (cleared areas) during experimental set up at the northernmost site in May 2006. Control treatments were never manipulated, recovery treatments recolonized naturally following initial organism removal, macrophyte-only treatments had annual removals of sessile invertebrates, and invertebrate-only treatments had annual removals of macroalgae and surfgrasses. b, Map of 13 rocky intertidal sites grouped into regions on four capes. c-f, Examples of kelp-dominated and mussel-dominated alternative states observed in one representative recovery treatment plot at the southernmost site in July 2009 (c), July 2014 (d), June 2018 (e) and June 2022 (f). As in f, mussels in every plot dominated by mussels in 2022 were measured and then marked with red pastel to avoid repeat measurement.

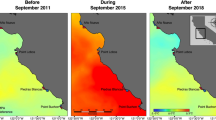

Extended Data Fig. 2 Intertidal water temperature anomalies (mean ± s.e.m.) from 2006 to 2020.

Daily anomalies were calculated as the difference between the daily temperature per cape (n = 5,375 d for Cape Foulweather, 5,376 d for Cape Perpetua, 5,392 d for Cape Blanco and 4,936 d for Cape Mendocino) and the long-term climatology per cape. Daily anomalies were then averaged within year and cape. Positive anomalies indicate warmer than average temperatures, while negative anomalies indicate colder than average temperatures.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Indicators of Pisaster ochraceus populations from 2006 to 2020.

Data were collected in annual or semiannual surveys during spring (earlier point) or summer (later point) per year. a, Sea star wasting disease (SSWD) prevalence (mean ± s.e.m.) was calculated as the per cent of diseased or recovering individuals in the population (n = 44,586 Pisaster). b, Density (mean ± s.e.m.) was calculated as the number of individuals that occurred within belt transects of known area (n = 42,306 Pisaster). c, Diameter (mean ± s.e.m.) was calculated from center length or madreporite length (n = 43,696 Pisaster).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Posterior distributions for the community state emission probabilities on Cape Foulweather.

Group-level posterior densities for alternative states 1 and 2 in the control (a,b), recovery (c,d), macrophyte-only (e,f) and invertebrate-only (g,h) treatments. Group-level densities are the means of 15 experimental plot densities.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Posterior distributions for the community state emission probabilities on Cape Perpetua.

Group-level posterior densities for alternative states 1 and 2 in the control (a,b), recovery (c,d), macrophyte-only (e,f) and invertebrate-only (g,h) treatments. Group-level densities are the means of 15 experimental plot densities.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Posterior distributions for the community state emission probabilities on Cape Blanco.

Group-level posterior densities for alternative states 1 and 2 in the control (a,b), recovery (c,d), macrophyte-only (e,f) and invertebrate-only (g,h) treatments. Group-level densities are the means of 20 experimental plot densities.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Posterior distributions for the community state emission probabilities on Cape Mendocino.

Group-level posterior densities for alternative states 1 and 2 in the control (a,b), recovery (c,d), macrophyte-only (e,f) and invertebrate-only (g,h) treatments. Group-level densities are the means of 15 experimental plot densities.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–6 and Extended Data Figs. 2–7

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Meunier, Z.D., Hacker, S.D. & Menge, B.A. Regime shifts in rocky intertidal communities associated with a marine heatwave and disease outbreak. Nat Ecol Evol 8, 1285–1297 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02425-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02425-5

This article is cited by

-

Marine heatwaves as hot spots of climate change and impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services

Nature Reviews Biodiversity (2025)

-

Age of extremes

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)