Abstract

Morphological disparity and taxonomic diversity are distinct measures of biodiversity, typically expected to evolve synergistically. However, evidence from mass extinctions indicates that they can be decoupled, and while mass extinctions lead to a drastic loss of diversity, their impact on disparity remains unclear. Here we evaluate the dynamics of morphological disparity and extinction selectivity across the Permian–Triassic mass extinction. We developed an automated approach, termed DeepMorph, for the extraction of morphological features from fossil images using a deep learning model and applied it to a high-resolution temporal dataset encompassing 599 genera across six marine clades. Ammonoids, brachiopods and ostracods experienced a selective loss of complex and ornamented forms, while bivalves, gastropods and conodonts did not experience morphologically selective extinctions. The presence and intensity of morphological selectivity probably reflect the variations in environmental tolerance thresholds among different clades. In clades affected by selective extinctions, the intensity of diversity loss promoted the loss of morphological disparity. Conversely, under non-selective extinctions, the magnitude of diversity loss had a negligible impact on disparity. Our results highlight that the Permian–Triassic mass extinction had heterogeneous morphological selective impacts across clades, offering new insights into how mass extinctions can reshape biodiversity and ecosystem structure.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

The DeepMorph was implemented in Python (v. 3.6.5) and R (v. 4.2.0). Other libraries include Pytorch (v. 1.10.2), torchvision (v. 0.11.3+cu113), opencv-python (v. 4.5.2.54), geomorph (v. 4.0.5) and dispRity (v. 1.7.0) was also used for feature extraction and disparity quantifiation. Models and scripts are available at GitHub (https://github.com/XiaokangLiuCUG/DeepMorph).

References

Briggs, D. E., Fortey, R. A. & Wills, M. A. Morphological disparity in the Cambrian. Science 256, 1670–1673 (1992).

Foote, M. Discordance and concordance between morphological and taxonomic diversity. Paleobiology 19, 185–204 (1993).

Gould, S. J. Trends as changes in variance: a new slant on progress and directionality in evolution. J. Paleontol. 62, 319–329 (1988).

Guillerme, T. et al. Disparities in the analysis of morphological disparity. Biol. Lett. 16, 20200199 (2020).

Hopkins, M. J. & Gerber, S. in Evolutionary Developmental Biology: A Reference Guide (eds Nuño de la Rosa, L. & Müller, G. B.) 965–976 (Springer, 2021).

Cole, S. R. & Hopkins, M. J. Selectivity and the effect of mass extinctions on disparity and functional ecology. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf4072 (2021).

Deline, B. & Ausich, W. I. Testing the plateau: a reexamination of disparity and morphologic constraints in early Paleozoic crinoids. Paleobiology 37, 214–236 (2011).

Stubbs, T. L. & Benton, M. J. Ecomorphological diversifications of Mesozoic marine reptiles: the roles of ecological opportunity and extinction. Paleobiology 42, 547–573 (2016).

Erwin, D. H. Disparity: morphological pattern and developmental context. Palaeontology 50, 57–73 (2007).

Carvalho, M. R. et al. Extinction at the end-Cretaceous and the origin of modern neotropical rainforests. Science 372, 63–68 (2021).

Bapst, D. W., Bullock, P. C., Melchin, M. J., Sheets, H. D. & Mitchell, C. E. Graptoloid diversity and disparity became decoupled during the Ordovician mass extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3428–3433 (2012).

Grossnickle, D. M. & Newham, E. Therian mammals experience an ecomorphological radiation during the Late Cretaceous and selective extinction at the K–Pg boundary. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160256 (2016).

Pimiento, C. et al. Selective extinction against redundant species buffers functional diversity. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20201162 (2020).

Puttick, M. N., Guillerme, T. & Wills, M. A. The complex effects of mass extinctions on morphological disparity. Evolution 74, 2207–2220 (2020).

Korn, D., Hopkins, M. J. & Walton, S. A. Extinction space—a method for the quantification and classification of changes in morphospace across extinction boundaries. Evolution 67, 2795–2810 (2013).

Raup, D. M. & Sepkoski, J. J. Mass extinctions in the marine fossil record. Science 215, 1501–1503 (1982).

Erwin, D. H. Extinction: How Life on Earth Nearly Ended 250 Million Years Ago (Princeton Univ. Press, 2006).

Song, H. et al. Respiratory protein-driven selectivity during the Permian–Triassic mass extinction. Innovation 5, 100618 (2024).

Song, H., Wignall, P. B., Tong, J. & Yin, H. Two pulses of extinction during the Permian–Triassic crisis. Nat. Geosci. 6, 52–56 (2013).

Fan, J.-x et al. A high-resolution summary of Cambrian to Early Triassic marine invertebrate biodiversity. Science 367, 272–277 (2020).

Stanley, S. M. Estimates of the magnitudes of major marine mass extinctions in Earth history. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E6325–E6334 (2016).

Luo, M., Shi, G. R., Buatois, L. A. & Chen, Z. Trace fossils as proxy for biotic recovery after the end-Permian mass extinction: a critical review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 203, 103059 (2020).

Villier, L. & Korn, D. Morphological disparity of ammonoids and the mark of Permian mass extinctions. Science 306, 264–266 (2004).

Dai, X., Korn, D. & Song, H. Morphological selectivity of the Permian–Triassic ammonoid mass extinction. Geology 49, 1112–1116 (2021).

Wan, J. et al. Decoupling of morphological disparity and taxonomic diversity during the end-Permian mass extinction. Paleobiology 47, 402–417 (2021).

Smithwick, F. M. & Stubbs, T. L. Phanerozoic survivors: actinopterygian evolution through the Permo–Triassic and Triassic–Jurassic mass extinction events. Evolution 72, 348–362 (2018).

Romano, C. et al. Permian–Triassic Osteichthyes (bony fishes): diversity dynamics and body size evolution. Biol. Rev. 91, 106–147 (2016).

Hsiang, A. Y. et al. AutoMorph: accelerating morphometrics with automated 2D and 3D image processing and shape extraction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 605–612 (2018).

Sibert, E., Friedman, M., Hull, P., Hunt, G. & Norris, R. Two pulses of morphological diversification in Pacific pelagic fishes following the Cretaceous–Palaeogene mass extinction. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20181194 (2018).

Weeks, B. C. et al. A deep neural network for high‐throughput measurement of functional traits on museum skeletal specimens. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 347–359 (2023).

Newell, A., Yang, K. & Deng, J. in Computer Vision – ECCV 2016 (ed. Leibe, B. et al.) 483–499 (Springer, 2016).

Huang, S., Gong, M. & Tao, D. A coarse-fine network for keypoint localization. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ed. O’Conner, L.) 3028–3037 (IEEE Computer Society, 2017).

Le, V.-L., Beurton-Aimar, M., Zemmari, A., Marie, A. & Parisey, N. Automated landmarking for insects morphometric analysis using deep neural networks. Ecol. Inform. 60, 101175 (2020).

Nguyen, H. H. et al. A lightweight keypoint matching framework for insect wing morphometric landmark detection. Ecol. Inform. 70, 101694 (2022).

Brayard, A. et al. Good genes and good luck: ammonoid diversity and the end-Permian mass extinction. Science 325, 1118–1121 (2009).

Jattiot, R., Bucher, H. & Brayard, A. Smithian (Early Triassic) ammonoid faunas from Timor: taxonomy and biochronology. Palaeontogr. A 317, 1–137 (2020).

Brosse, M., Brayard, A., Fara, E. & Neige, P. Ammonoid recovery after the Permian–Triassic mass extinction: a re-exploration of morphological and phylogenetic diversity patterns. J. Geol. Soc. 170, 225–236 (2013).

McGowan, A. J. Ammonoid taxonomic and morphologic recovery patterns after the Permian–Triassic. Geology 32, 665–668 (2004).

Jablonski, D. Survival without recovery after mass extinctions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8139–8144 (2002).

He, W., Shi, G. & Bu, J. in Brachiopods Around the Permian–Triassic Boundary of South China (eds He, W. et al.) 51–60 (Springer, 2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Significant pre-mass extinction animal body-size changes: evidences from the Permian–Triassic boundary brachiopod faunas of South China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 448, 85–95 (2016).

Foster, W., Lehrmann, D., Yu, M., Ji, L. & Martindale, R. Persistent environmental stress delayed the recovery of marine communities in the aftermath of the latest Permian mass extinction. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. 33, 338–353 (2018).

Huang, Y., Tong, J., Fraiser, M. L. & Chen, Z.-Q. Extinction patterns among bivalves in South China during the Permian–Triassic crisis. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 399, 78–88 (2014).

Tu, C., Chen, Z.-Q. & Harper, D. A. Permian–Triassic evolution of the Bivalvia: extinction-recovery patterns linked to ecologic and taxonomic selectivity. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 459, 53–62 (2016).

Foster, W. J. & Twitchett, R. J. Functional diversity of marine ecosystems after the Late Permian mass extinction event. Nat. Geosci. 7, 233–238 (2014).

Orchard, M. J. Conodont diversity and evolution through the latest Permian and Early Triassic upheavals. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 252, 93–117 (2007).

Payne, J. L. & Finnegan, S. The effect of geographic range on extinction risk during background and mass extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10506–10511 (2007).

Jablonski, D. & Raup, D. M. Selectivity of end-Cretaceous marine bivalve extinctions. Science 268, 389–391 (1995).

Song, H. et al. Anoxia/high temperature double whammy during the Permian–Triassic marine crisis and its aftermath. Sci. Rep. 4, 4132 (2014).

Knoll, A. H., Bambach, R. K., Payne, J. L., Pruss, S. & Fischer, W. W. Paleophysiology and end-Permian mass extinction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 256, 295–313 (2007).

Song, H., Wignall, P. B. & Dunhill, A. M. Decoupled taxonomic and ecological recoveries from the Permo–Triassic extinction. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5091 (2018).

Dai, X. et al. A Mesozoic fossil lagerstätte from 250.8 million years ago shows a modern-type marine ecosystem. Science 379, 567–572 (2023).

Ciampaglio, C. N., Kemp, M. & McShea, D. W. Detecting changes in morphospace occupation patterns in the fossil record: characterization and analysis of measures of disparity. Paleobiology 27, 695–715 (2001).

Ruta, M., Angielczyk, K. D., Fröbisch, J. & Benton, M. J. Decoupling of morphological disparity and taxic diversity during the adaptive radiation of anomodont therapsids. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20131071 (2013).

Bazzi, M., Kear, B. P., Blom, H., Ahlberg, P. E. & Campione, N. E. Static dental disparity and morphological turnover in sharks across the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Curr. Biol. 28, 2607–2615.e3 (2018).

Khanna, N., Godbold, J. A., Austin, W. E. & Paterson, D. M. The impact of ocean acidification on the functional morphology of foraminifera. PLoS ONE 8, e83118 (2013).

Fox, L., Stukins, S., Hill, T. & Miller, C. G. Quantifying the effect of anthropogenic climate change on calcifying plankton. Sci. Rep. 10, 1620 (2020).

Jurikova, H. et al. Permian–Triassic mass extinction pulses driven by major marine carbon cycle perturbations. Nat. Geosci. 13, 745–750 (2020).

Payne, J. L. et al. Calcium isotope constraints on the end-Permian mass extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8543–8548 (2010).

Dal Corso, J. et al. Environmental crises at the Permian–Triassic mass extinction. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 197–214 (2022).

Dick, D. G., Darroch, S., Novack-Gottshall, P. & Laflamme, M. Does functional redundancy determine the ecological severity of a mass extinction event? Proc. R. Soc. B 289, 20220440 (2022).

Dunhill, A. M., Foster, W. J., Sciberras, J. & Twitchett, R. J. Impact of the Late Triassic mass extinction on functional diversity and composition of marine ecosystems. Palaeontology 61, 133–148 (2018).

Larson, D. W., Brown, C. M. & Evans, D. C. Dental disparity and ecological stability in bird-like dinosaurs prior to the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Curr. Biol. 26, 1325–1333 (2016).

Benton, M. J. Vertebrate Palaeontology (John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

Payne, J. L., Bush, A. M., Heim, N. A., Knope, M. L. & McCauley, D. J. Ecological selectivity of the emerging mass extinction in the oceans. Science 353, 1284–1286 (2016).

Pimiento, C. et al. Functional diversity of marine megafauna in the Anthropocene. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay7650 (2020).

Woodhouse, A. et al. Adaptive ecological niche migration does not negate extinction susceptibility. Sci. Rep. 11, 15411 (2021).

Raja, N. B. et al. Morphological traits of reef corals predict extinction risk but not conservation status. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 1597–1608 (2021).

Malanoski, C. M., Farnsworth, A., Lunt, D. J., Valdes, P. J. & Saupe, E. E. Climate change is an important predictor of extinction risk on macroevolutionary timescales. Science 383, 1130–1134 (2024).

Huang, S., Roy, K. & Jablonski, D. Origins, bottlenecks, and present-day diversity: patterns of morphospace occupation in marine bivalves. Evolution 69, 735–746 (2015).

Carlson, S. J. The evolution of Brachiopoda. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 44, 409–438 (2016).

Ramezani, J. & Bowring, S. A. Advances in numerical calibration of the Permian timescale based on radioisotopic geochronology. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 450, 51–60 (2018).

Burgess, S. D., Bowring, S. & Shen, S. Z. High-precision timeline for Earth’s most severe extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3316–3321 (2014).

Yin, H., Zhang, K., Tong, J., Yang, Z. & Wu, S. The global stratotype section and point (GSSP) of the Permian–Triassic boundary. Episodes 24, 102–114 (2001).

Henderson, C. M. Permian conodont biostratigraphy. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 450, 119–142 (2018).

Yin, H. & Wu, S. Transitional bed—the basal Triassic unit of South China. J. China Univ. Geosci. 10, 163–172 (1985).

Liu, X., Song, H., Bond, D. P. G., Tong, J. & Benton, M. J. Migration controls extinction and survival patterns of foraminifers during the Permian–Triassic crisis in South China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 209, 103329 (2020).

Teichert, C., Kummnel, B. & Kapoor, H. Mixed Permian–Triassic fauna, Guryul Ravine, Kashmir. Science 167, 174–175 (1970).

Chen, Z. Q., Kaiho, K. & George, A. D. Survival strategies of brachiopod faunas from the end-Permian mass extinction. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 224, 232–269 (2005).

Widmann, P. et al. Dynamics of the largest carbon isotope excursion during the Early Triassic biotic recovery. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 196 (2020).

Qin, X. et al. U2-Net: going deeper with nested U-structure for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 106, 107404 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Automatic taxonomic identification based on the Fossil Image Dataset (>415,000 images) and deep convolutional neural networks. Paleobiology 49, 1–22 (2023).

Paszke, A. et al. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 8024–8035 (Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation, 2019).

Bradski, G. & Kaehler, A. Learning OpenCV: Computer Vision with the OpenCV Library (O’Reilly Media, 2008).

Gower, J. C. Generalized Procrustes analysis. Psychometrika 40, 33–51 (1975).

Rohlf, F. J. & Slice, D. Extensions of the Procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst. Zool. 39, 40–59 (1990).

Kuhl, F. P. & Giardina, C. R. Elliptic Fourier features of a closed contour. Comput. Graph. Image Process. 18, 236–258 (1982).

Grieve, S. spatial-efd: a spatial-aware implementation of elliptical Fourier analysis. J. Open Source Softw. 2, 189 (2017).

Foote, M. Morphological and taxonomic diversity in clade’s history: the blastoid record and stochastic simulations. Contrib. Mus. Paleontol. 28, 101–140 (1991).

Liu, X. Heterogeneous selectivity and morphological evolution of marine clades during the Permian–Triassic mass extinction. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10531896 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge J. Wan, J. Yin, S. Jiang and X. Li for collecting the literature. We thank J. Sun and Y. Sun for helping to collect the fossil images. This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42325202, 92155201, 92255303), the State Key R&D Project of China (2023YFF0804000), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei (2023AFA006) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan). X.L. thanks the financial support from the China Scholarship Council (202206410024). D.S. received funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PCEFP3_187012), the Swedish Research Council (VR: 2019-04739) and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research MISTRA within the framework of the research programme BIOPATH (F 2022/1448). We acknowledge the contributors to the Paleobiology Database. This is Paleobiology Database publication number 485.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. and X.L. conceived this study. X.L., X.D. and F.W. collected data. X.L., H.S. and D.S. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. X.L. and D.S. analysed the data. X.L. and H.S. designed the figures. All authors revised and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Adam Woodhouse and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Percentages of PCA variances of six clades that are explained by the first 10 axes.

a–f, Percentages of PCA variances of ammonoids (a), brachiopods (b), ostracods (c), bivalves (d), gastropods (e), and conodonts (f).

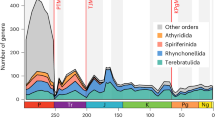

Extended Data Fig. 2 Evolution of disparity (SOR, blue squares) and diversity (orange diamonds) over time and across subsets.

Vertical bars represent 95% of the quantiles, which are calculated from 10,000 bootstrap replicates for each subset. a–f, Disparity and diversity of ammonoids (a), brachiopods (b), ostracods (c), bivalves (d), gastropods (e), and conodonts (f). Abbreviations: SOR = Sum of ranges. Fossil silhouettes adapted from ref. 18 under a Creative Commons licence CC BY 4.0.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Marginal selective intensity simulations under different magnitude losses of diversity and disparity (SOR).

a–d, Selectivity intensities among morphologies. Strong selectivity (a) indicates the highest extinction risk is ten times higher than the lowest extinction possibility. Moderate selectivity (b) indicates the highest extinction risk is five times higher than the lowest extinction risk. Weak selectivity (c) represents the highest extinction risk for a taxon that is two times higher than the one with the lowest extinction risk. Random extinction (d) represents a non-selective extinction. The rest of the extinction rates are distributed linearly. e, Disparity loss under different magnitude of diversity loss and selectivity. f, Diversity loss under different magnitude of disparity loss and selectivity.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Frequency distribution of the centroid distance shifts under 10,000 replicates from pre-extinction ammonoids.

Gray histograms indicate the 95% quantile. The red arrows represent the empirical results.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Marginal selective intensity simulations based on empirical morphological occupations under different magnitude losses of diversity.

extinction probabilities were based on the linear distributed model. a–f, Disparity loss rates of ammonoids (a), brachiopods (b), ostracods (c), bivalves (d), gastropods (e), and conodonts (f).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Morphological variations of victims, survivors, and newcomers for six clades during the PTME.

a–f, Morphological variations of ammonoids (a), brachiopods (b), ostracods (c), bivalves (d), gastropods (e), and conodonts (f). All the specimens are not to scale. Taxonomy list for ammonoids, a1–a11: Urartoceras abichianum, Araxoceras latissimum, Changhsingoceras sichuangense, Schizoloboceras vediensis, Araxoceltites sanestapanus, Metotoceras woodwardi, Episageceras dalailamae, Dunedinites pinguis, Anotoceras kama, Tellerites sp., and Pseudovishnuites guidingensis. For brachiopods, b1–b12: Fusispirifer sp., Glyptorhynchia lens, Janiceps peracuta, Paramarginifera japonica, Cathaysia chonetoides, Marginifera ornata, Permianella typica, Paryphella orbicularis, Piarorhynchella selongensis, Lichuanorelloides lichuanensis, and Orbicoelia speciosa. For ostracods, c1–c11: Cooperuna tenuis, Baschkirina ballei, Triplacera sp., Polycope baudi, Coronakirkbya hamori, Acanthoscapha blessi, Fabalicypris parva, Basslerella superarella, Samarella meishanella, Permoyoungiella bogschi, and Hollinella martensiformis. For bivalves, d1–d10: Pteronites pinnaeformis, Parallelodon laochangensis, Dyasmya elegans, Unionites canalensis, Solemya togata, Ensipteria guizhouensis, Entolioides subdemissus, Nucinella taylori, Isognomon ephippium, and Permophorus bregeri. For gastropods, e1–e11: Palaeostylus pupoides, Streptacis whitfieldi, Retispira sinensis, Porcellia paucituberculata, Stachella micra, Tropidodiscus curvilineatus, Anomphalus fusuiensis, Worthenia humilis, Meekospira solenisciforma, Microlampra heshanensis, and Wannerispira shangganensis. For conodonts, f1–f9: Hadrodontina aequabilis, Gondolella constricta, Sweetocristatus arcticus, Cypridodella spengleri, Iranognathus sosioensis, Pachycladina rendona, Isarcicella isarcica, Clarkina meishanensis, and Furnishius triserratus.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Ammonoid morphological occupation across three intervals based on multiple species and specimens.

a, Multiple species from one genus and multiple specimens for the same species. b, The result of interspecific variations of some representatives. Plots based on the raw data, including 191 species and 219 specimens. Notably, genera dating from the Changhsingian and characterized by stronger shell ornamentations exhibited higher levels of interspecific variation, as exemplified by Paratirolites and Alibashites. Conversely, genera from the Induan fauna displayed fewer variations, as observed in Ambites and Mullericeras.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Disparity comparison between genus-based and species rarefied results and selectivity test based on the rarefied results.

a, The square dots represent results based on genus-level, and diamond dots indicate rarefied disparity changes. Vertical bars represent 95% quantiles, calculated from 10,000 bootstrap replicates for each subset (that is, one-side test). b, Frequency distribution of the SOV by subsampling six species (Nsurvivors = 6) from Changhsingian, and the Pquantile < 0.08. c, Frequency distribution of the SOV by subsampling 52 species (NInduan = 52) from Changhsingian, Pquantile < 0.05. d, Frequency distribution of the centroid distance shifts under random replicates from pre-extinction taxa, Pquantile « 0.01 (NInduan = 52).

Extended Data Fig. 9 SOV comparison between the results using two PCA axes and ten PCA axes from ammonoids and conodonts.

a, Sum of variance of ammonoids, first two and ten PCA axes include 89.4% and 98.0% of total variations, respectively. b, Sum of variance of conodonts, first two and ten PCA axes include 66.6% and 7.6% of total variations, respectively. Vertical bars represent 95% quantiles, calculated from 10,000 bootstrap replicates for each subset.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Song, H., Chu, D. et al. Heterogeneous selectivity and morphological evolution of marine clades during the Permian–Triassic mass extinction. Nat Ecol Evol 8, 1248–1258 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02438-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02438-0

This article is cited by

-

Emerging uses of artificial intelligence in deep time biodiversity research

Nature Reviews Biodiversity (2025)

-

Advancing paleontology: a survey on deep learning methodologies in fossil image analysis

Artificial Intelligence Review (2025)