Abstract

Many terrestrial plant communities, especially forests, have been shown to lag in response to rapid climate change. Grassland communities may respond more quickly to novel climates, as they consist mostly of short-lived species, which are directly exposed to macroclimate change. Here we report the rapid response of grassland communities to climate change in the California Floristic Province. We estimated 349 vascular plant species’ climatic niches from 829,337 occurrence records, compiled 15 long-term community composition datasets from 12 observational studies and 3 global change experiments, and analysed community compositional shifts in the climate niche space. We show that communities experienced significant shifts towards species associated with warmer and drier locations at rates of 0.0216 ± 0.00592 °C yr−1 (mean ± s.e.) and −3.04 ± 0.742 mm yr−1, and these changes occurred at a pace similar to that of climate warming and drying. These directional shifts were consistent across observations and experiments. Our findings contrast with the lagged responses observed in communities dominated by long-lived plants and suggest greater biodiversity changes than expected in the near future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Climate change is expected to alter species distributions, resulting in cascading risks to global biodiversity and ecosystem functioning1,2,3. Terrestrial plant species have been repeatedly shown to respond slowly despite the rapid pace of warming2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. As a consequence, delayed species extinctions and abrupt community reshuffling are expected in the future5. However, this consensus is mostly supported by evidence from forest ecosystems, with the response of other ecosystems relatively understudied. Compared with forests, grassland ecosystems have the potential to be highly responsive to climate change, as they are often dominated by relatively short-lived species18,19 and might be more directly exposed to harsh climatic conditions14,20,21. Identifying such rapid ecological changes in non-forest communities is important for early detection and accurate projection of climate change impacts. Therefore, we ask whether grassland communities closely track climate change, shifting in composition in a consistent direction at a rapid pace.

However, few studies have focused on the pace of compositional shifts in grasslands relative to climate change (but see ref. 22). Furthermore, inconsistent findings from observational and experimental studies suggest that compositional shifts are highly variable. For example, some long-term observations have shown relative increases in grasses at the cost of forbs under concurrent warming and drying23,24,25, while climate change manipulative experiments have suggested seemingly inconsistent compositional shifts26,27,28,29. The persistent challenge in assessing how grassland communities track climate change requires long-term, extensive records and inference methods to analyse them robustly.

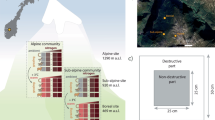

To test whether grassland community compositions respond rapidly and consistently to climate change, we collected compositional data from long-term quantitative observations and manipulative experiments in the California Floristic Province (CFP), a global biodiversity hotspot30,31 (Extended Data Fig. 1). Encompassing broad geographic, climatic and edaphic gradients, the CFP harbours over 5,000 native vascular plant species with over 30% endemism32, but is heavily invaded by non-native species33. We first compiled 12 long-term observational records (Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 2) across the regional climate gradient during a period of climate warming and drying (equation (1), Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We leveraged 829,337 occurrence records in a large-scale community science programme and 30 year temperature and precipitation climatologies to estimate the realized climatic niches of 349 species in the CFP (Supplementary Table 3). We then quantified how communities shifted in composition through changes in the community temperature index (CTI) and community precipitation index (CPI), calculated from species’ realized climatic niches and their relative abundance (equations (2) and (3)). This approach does not require a complete species turnover to detect compositional changes; rather, it is sensitive to more nuanced changes in species’ relative abundance. We compared community compositional changes with the observed climate changes. In parallel, we applied the same approach to three long-term global change experiments within the CFP and estimated the effects of climate manipulations on community compositions. Finally, we analysed the abundance changes of individual species and synthesized observational and experimental community compositional shifts in the climate niche space.

Given the considerable observed climate warming and drying in the CFP (Extended Data Fig. 1), we hypothesize that the CFP grassland communities would shift towards species associated with warmer and drier locations (thermophilization and xerophilization, respectively) at a comparable rate to that of climate change, by contrast to the lagged response in forests. We also anticipate that community compositional shifts, both those observed over time and those manipulated by experiments, would be consistent in direction. These hypotheses, tested with a combination of long-term observations and manipulative experiments, enable us to answer the ecological question of how grassland communities, a potentially highly responsive system, track climate change.

Estimates of species’ climatic niches

Species had distinct geographic distributions that indicate their climatic niches across the CFP grasslands (Fig. 1a,b). Species’ temperature niche centroids (medians of mean annual temperature at recorded occurrences) ranged from 8.15 °C to 17.3 °C, and the precipitation niche centroids (medians of annual precipitation at recorded occurrences) ranged from 266 mm to 1,410 mm (Fig. 1c). Additional analyses supported the robustness of our niche estimates against alternative occurrence datasets (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1), climate datasets (Supplementary Fig. 2), climate variables (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), summary statistics (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6), spatial and climate thinning (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8) and time periods (Supplementary Fig. 9). Across all the species, the temperature and precipitation niche centroids were negatively and significantly correlated (Fig. 1c, Pearson’s correlation r = −0.671, P ≤ 0.001). This correlation suggests that species associated with warmer locations were also associated with drier locations, probably reflecting the negative correlation between temperature and precipitation in the semi-arid Mediterranean climate of the CFP and species’ long-term adaptation to this regime.

a, Occurrence of grassland species in the CFP, retrieved from the GBIF data (grey points), highlighting two example species, D. californica in the north (blue points) and S. pulchra in the south (red points). b, Species occurrence in climate space of mean annual temperature and annual precipitation, retrieved from the CHELSA data (grey), highlighting the same two example species, D. californica under cool and wet climates (blue) and S. pulchra under warm and dry climates (red). c, Estimated climatic niche centroids from the medians of temperature and precipitation for each species (grey), highlighting the two species (blue and red).

We illustrate this pattern in climatic niche space with two species of grasses: Danthonia californica and Stipa pulchra. They occupy distinct geographical areas (Fig. 1a) and niches in the climate space (Fig. 1b,c and Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5). D. californica, a northern CFP species, occurs in relatively cooler and wetter areas having a mean annual temperature of 12.5 °C (5.50–15.3 °C) (median and 90% interval) and annual precipitation of 1,110 mm (510–2,750 mm). By comparison, S. pulchra, a more southern species, inhabits warmer and drier locations, characterized by a mean annual temperature of 15.3 °C (12.9–17.4 °C) and annual precipitation of 549 mm (279–1,110 mm). Among all the species, the clear niche differentiation lays the foundation for using the species’ climatic niche estimates to subsequently quantify community compositional shifts along observational and experimental climate variations (Fig. 1c).

Observational and experimental evidence of community shifts

Using our species’ climatic niche estimates, we analysed changes in community indices in long-term observations to test whether community thermophilization and xerophilization were tracking the observed climate change (Fig. 2). The grassland communities were monitored over 8–33 years, across 12 sites with 176 total plot years (Angelo Coast; Carrizo Plain; Elkhorn Slough; Jasper Ridge; McLaughlin; Morgan Territory; Pleasanton Ridge; Sunol; Swanton Ranch; University of California (UC), Santa Cruz; Vasco Caves; Fig. 2, Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3, and Extended Data Table 1). These observational sites spanned an approximately 30,000 km2 geographical area and varied with respect to location (inland or coastal), soil type (serpentine or non-serpentine) and dominant vegetation (annual or perennial grasses).

Consistent with climate warming and drying, grassland communities shift dominance to species associated with warmer (increasing CTI) and drier (decreasing CPI) locations in 12 long-term observational sites across the CFP (red trend lines determined by linear regression and significant slopes by two-sided t-test; NS: P > 0.05, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001). Refer to Extended Data Table 1 for sample sizes. The box plots show the median (centre), the first and third quartiles (bounds of the box), the range extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles (whiskers) and outliers beyond this range (points). The map shows the geographical distribution of the 12 sites with grassland percentage cover (green) from MODIS land-cover-type data.

Across the observational network, we estimated an overall thermophilization of 0.0216 ± 0.00592 °C yr−1 (mean ± s.e., P = 0.0053) and xerophilization of −3.04 ± 0.742 mm yr−1 (P = 0.0019) in these grassland communities using linear mixed-effects models with site-level random intercepts (equation (4)). Notably, these trends were comparable to the climate warming and drying at these sites in their order of magnitudes, with mean annual temperature increasing at 0.0177 ± 0.00260 °C yr−1 and annual precipitation decreasing at −4.22 ± 1.48 mm yr−1 (equation (1) and Extended Data Fig. 3). When examined individually with linear regression, 8 of the 12 sites had significant increases in CTI and significant decreases in CPI over the years (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Four sites experienced no significant CTI or CPI changes, which might reflect the importance of factors other than regional climate change in determining species composition, such as climate oscillations, soil type, microclimate, topography, propagule pressure and disturbance regime34,35,36. For example, serpentine soils might limit species’ establishment, especially non-native annual grass and forb species, and thus dampen shifts in CTI and CPI compared with communities in non-serpentine soils (Fig. 2e,f)37,38. In addition, non-native species that are typically much more abundant in non-serpentine soils might respond faster than native species to climate warming and drying, contributing to more rapid CTI and CPI changes39,40,41. The observational evidence reveals a rapid, region-wide trend of grassland community shifts towards warmer and drier species compositions, consistently aligning with the observed climate warming and drying trends in the region.

To disentangle the influence of local factors and focus on the climatic drivers of community shifts, we analysed a series of manipulative experiments using the same approach. The warming experiment (part of the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment) was conducted for 16 consecutive years, from 1999 to 2014, in ~7,500 m2 within a 50,000 m2 grassland and experienced a large variation of plot-level temperature (8.69–12.3 °C) and precipitation (240–1,380 mm) in 2,174 total plot years42. The warming treatment increased in strength over three phases: phase 1 with +80 W m−2 heating, phase 2 with +100 W m−2 heating and phase 3 with +250 W m−2 heating.

Across three phases of the warming experiment, communities in warming plots (n = 64, possibly compounded by drying), compared with those in ambient plots (n = 72), did not differ significantly in phase 1 or 2. However, there was a significant increase in CTI of 0.148 ± 0.0249 °C and a significant decrease in CPI of −17.3 ± 2.76 mm in phase 3 (Fig. 3), estimated using linear mixed-effects models with year-level random intercepts (equation (5) and Supplementary Table 6). In addition to providing strong support for our hypothesis, we showed that experimental warming caused thermophilization and xerophilization in as short as a year, with the effects being more significant under stronger treatments.

Warming treatment causes communities to shift dominance to species associated with warmer (CTI) and drier (CPI) locations in the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment. The orange background shades denote phase 1 (+80 W m−2 heating) in 1999–2002, phase 2 (+100 W m−2 heating) in 2003–2009 and phase 3 (+250 W m−2 heating) in 2010–2014. Ambient plots (n = 72) and warming plots (n = 64) are in black and red, respectively. Effects of warming during each phase of treatment were estimated by linear mixed-effects models (two-sided t-test; NS: P > 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001). Box plots show the median (centre), the first and third quartiles (bounds of the box), the range extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles (whiskers), and outliers beyond this range (points).

We synthesized evidence from the effects of watering or drought treatments in the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment and two International Drought Experiments43 on CTI and CPI (Extended Data Figs. 6–8). Drought treatments led to either no significant change or warmer and drier communities (increased CTI, decreased CPI), whereas watering treatments drove the opposite community responses (Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 7). These patterns aligned with the coupled effects of thermophilization and xerophilization caused by warming. Compared with CPI, a community index calculated directly from a drought metric provided similar insight into xerophilization driven by warming and drying (Supplementary Figs. 10–12). The use of CTI and CPI revealed community compositional changes that were not evident when considering traditional species guilds (native versus non-native, annual versus perennial, grass versus forb) (Supplementary Figs. 13–15). Collectively, the results from observations and experiments indicate that the combined warming and drying in the CFP drive grassland communities towards species associated with warmer and drier locations. Importantly, the magnitude of this shift scales with the strength of climate change.

Analysis and synthesis of community shifts

Underlying the shifts in community composition are changes in species abundance44; thus, we identified key species that experienced abundance changes and drove community compositional shifts. Across the observational sites, certain species showed significant increases in abundance over time (for example, Bromus diandrus, two-sided t-test, P ≤ 0.05) or established after the first 5 years (for example, Eschscholzia californica); conversely, some species experienced decreases in abundance (for example, Festuca myuros) or extirpated before the last 5 years (for example, Hypochaeris radicata) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 16). In the experiment, certain species showed increases (for example, Brachypodium distachyon) or decreases (for example, Torilis arvensis) in abundance under the warming treatments compared with the ambient conditions (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 17). There was no evidence for dominant or rare species consistently driving community shifts (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). While the species contributing to these community shifts varied, the ones that became more abundant were generally associated with warmer and drier locations (two-sided Wilcoxon test, P ≤ 0.05) across the observations (Fig. 4c) and under the warming experiment (Fig. 4d).

a, Across the 12 observational sites, climatic niche centroids for species with a significant increase in abundance over time (open green circles), with a significant decrease in abundance over time (open orange circles), established (filled green circles), extirpated (filled orange circles) and all other species (open grey circles) (two-sided t-test, P ≤ 0.05). The circle size is proportional to the species’ relative abundance in the community. b, In phase 3 of the experiment, climatic niches for species with increases (green), decreases (orange) and no change in abundance (grey) (two-sided t-test, P ≤ 0.05). c, Across the observations, the summary of climatic niches for species with an increase (n = 94), a decrease (n = 103) and no change (n = 690) in abundance over time. Box plots show the median (centre), the first and third quartiles (bounds of the box), the range extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles (whiskers), and outliers beyond this range (points). The levels of significance and P values are from two-sided Wilcoxon tests for pairwise comparisons (NS: P > 0.05, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001). d, In the experiment, the summary of climatic niches for species with an increase (n = 15), a decrease (n = 37) and no change (n = 495) in abundance between ambient and warming plots. Descriptions for the box plots and statistics follow c.

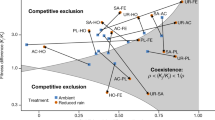

Despite differences in the identities of species driving community compositional changes, our synthesis in the niche space revealed consistent and comparable community compositional shifts from both long-term observations and manipulative experiments (Fig. 5). Representing the CTI–CPI values of these communities in climate niche space is akin to conducting an ordination analysis with only two dimensions, which are more biologically meaningful and directly linked to climate gradients (Figs. 1c and 5a). While the strength of the warming experiment lies in establishing causality in controlled climate change scenarios, the 12 observational studies conducted across a wide geographic range provide a comprehensive exploration of the climate space (Fig. 5a)45.

a, Community compositions at the 12 observational sites and the experimental site are described by the median CTI (°C) and CPI (mm), positioned in estimated species’ climatic niche centroids (median, grey). The inset rectangle shows the extent of b. b, Communities shift in a consistent direction in the climate space in the observations and experiment. For the observational sites, the arrows point from the start to the end of the sampling period; for the experiment site, the arrows point from ambient to warming treatments. The CTI–CPI extent is identical in c, whereas the inset rectangle shows the extent of d. c, Communities shift significantly in 8 of 12 observational sites. d, Communities shift significantly, primarily in the phase 3 warming of the experiment. In b–d, arrows are set to be semi-transparent for sites with non-significant linear temporal trends in either CTI or CPI and for phases with non-significant differences between the ambient and warming treatments in either CTI or CPI (two-sided t-test, P > 0.05). Refer to Figs. 1 and 2 for P values for each test.

We identified a shared pattern in which community thermophilization and xerophilization occurred along a common trajectory of CTI and CPI, which showed remarkable consistency under both long-term climate change and strong warming treatment (Fig. 5b). Among the significant shifts, a community thermophilization of 0.1 °C corresponded to a xerophilization of −12.3 mm (median) from the observations and −9.28 mm from the experiment. More pronounced climate change across the distributed observations (Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) and intensifying phases of the warming experiment resulted in stronger community thermophilization and xerophilization (Figs. 2, 3 and 5c,d). Examining multiple compositional shifts in the climate niche space reveals that while the magnitude of these shifts may depend on the observed time period (Fig. 5c) or the degree of warming (Fig. 5d), thermophilization and xerophilization are highly coupled changes in the study region, stemming from the structure of the distinctive climate niche space (Fig. 1a).

Discussion

Our study provides compelling evidence that grassland communities in the coastal CFP shift in a consistent direction and at a rapid pace comparable to climate change. Our findings contrast with the documented lagged responses in forests2,5,7,8,10,11,12,13,15,16. We reported these shifts in multiple communities across a vast geographic area, despite differences in climate, soil type, topography and land use history. Integrating evidence from climate change experiments, we uncovered a clear pattern of climate-driven community compositional shifts.

The rate of grassland community thermophilization in this study exceeds that in many studies of forest communities. Across the 12 observational sites analysed, the overall thermophilization rate (increasing CTI per year) of 0.0216 °C yr−1 (background climate warming of 0.0177 °C yr−1) is far greater than the thermophilization rate of 0.0039 °C yr−1 in western US forests (background climate warming of 0.032 °C yr−1)46. It also exceeds the rate of 0.0066 °C yr−1 in Andean forest communities12,47 and 0.009 °C yr−1 in European forest communities16. Notably, herbaceous plants in the forest understory also have such a lagged response to climate change5,10,11,16. The rate we observed is close to that of temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands, as estimated from occurrence records22. The rapid response of our grassland communities might be attributed to the faster population turnover of common species, greater exposure to macroclimatic changes and the dominance of non-native species. First, grasslands are dominated by annual and short-lived perennial plants, leading to faster changes in species’ relative abundance and shifts in community composition compared to forests dominated by long-lived trees1,18,19. In addition, plants’ seasonal dormancy in the dry summers of the Mediterranean climate48 might also accelerate compositional changes. Second, unlike forests, grasslands might have limited capacity for understory microclimates to attenuate the effects of macroclimate warming, leading to exposed microhabitats that experience more rapid warming14,20,21,49,50. Last, grasslands in the study region, especially those in non-serpentine soil, are dominated by non-native species adapted to warmer and drier climates, which were able to increase in distribution and abundance rapidly51.

Furthermore, our study reveals a region-wide xerophilization in the Mediterranean climate that is often overlooked in temperate studies. We observed significant overall xerophilization at a rate of −3.04 mm yr−1 across observational sites; in comparison, a continental-scale assessment of the New World plant communities did not conclude a consistent direction of either xerophilization or mesophilization (increase in CPI)22. Previously, it has been shown that thermophilization correlated with mesophilization (wetting), driven by the positive correlation between temperature and precipitation in temperate zones22. However, we reported an opposite coupling between thermophilization and xerophilization (drying) in the coastal CFP (Fig. 5). The distinct coupling could arise from the negative correlation between species’ temperature and precipitation niches shaped by the Mediterranean climate, together with the concomitant warming and drying trends in the region. Given that community compositional changes in the temperature and precipitation dimensions (Fig. 5b) were strongly constrained by the narrow climate niche space of the species pool available (Fig. 5a), any future combinations of climatic conditions that extend beyond existing species’ climatic niches might limit the pool of suitable species and, therefore, the ability of communities to track changes in multiple climatic variables52.

We recognize a few limitations in our study. First, our estimation of climatic niches did not account for species’ intraspecific variation or their ability to acclimate or adapt to changing abiotic conditions, which may constrain the application of our findings53,54. However, conducting such analyses would be feasible for only a limited number of well-studied species rather than entire communities. Second, while our long-term datasets encompassed a wide range of coastal grassland types in both observational and experimental sites, we lacked similar data from the complete range of interior grassland communities, such as valley grasslands or oak–grass savannas55. Last, we could not completely isolate the individual effects of warming and drying within this composite climate change driver, as the warming treatment in the experiment also resulted in some drying56. Despite these complexities, our study provides highly consistent observational and experimental evidence of rapid grassland community shifts driven by climate change.

The strong response of coastal CFP grassland communities to warming and drying suggests that these shifts might persist in the face of ongoing climate change. Unlike forest communities that are threatened by the growing climatic debt8,11,16, our study suggests that grassland communities might suffer from different vulnerabilities under climate change. The rapid changes in community composition predict the possibility of changes in local biodiversity and species interaction in immediate terms24,57,58,59. Furthermore, the coupled community compositional shifts, constrained by distinct species’ niche space, suggest that communities might be limited in the capacity to track multidimensional climatic change. Our findings of rapid grassland community shift offer novel insights into climate-driven biodiversity changes in a highly responsive ecosystem.

Methods

Study area

The CFP grasslands are a prime study system due to their expansive environmental gradients and remarkable species richness. Spanning an area of approximately 300,000 km2, the CFP extends across broad geographic (115–124° W longitude, 28–44° N latitude) and climatic (−8.35 to 20.3 °C temperature, 54.8– 3,600 mm precipitation) gradients. The CFP is home to a rich diversity of plant species and is known as a global biodiversity hotspot30,31. The CFP harbours an estimated 5,006 native vascular plant species, 1,846 of which are endemic32. Located on the Pacific Coast of North America, the CFP has a Mediterranean-type climate, which has experienced significant changes, notably warming and drying, over the past four decades (Extended Data Fig. 1).

In the CFP, grassland has the modal land cover type, occupying 12% of the total area (MODIS land-cover-type data)60. CFP grasslands are limited by both temperature and moisture. Disturbances such as wildfires are critical to maintaining the biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of CFP grasslands. The climatic gradient in the area leads to diverse grassland community compositions, including drier inland communities dominated by annuals, wetter coastal communities with higher abundances of perennials and communities adapted to unique soil types such as serpentine. CFP grasslands provide key ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, nitrogen cycling and wildlife habitat55. At the same time, grasslands in the CFP are a highly threatened ecosystem, owing to conversion to agriculture, alteration in disturbance regimes (for example, fire, grazing) and invasive non-native species, which dominate the vast majority of grasslands in the CFP. In this study, we aim to investigate climate change impacts on the coastal CFP grassland communities by focusing on 12 long-term observational sites and 3 global change experiments distributed across a wide coastal area within the CFP (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3).

Observational and experimental sites

We collected grassland community composition from 12 sites in the CFP with 8–33 years of observations from 1983 to 2021 (Extended Data Fig. 2). These sites are Angelo Coast61, Carrizo Plain62, Elkhorn Slough63, Jasper Ridge serpentine64,65, McLaughlin annual66, McLaughlin serpentine66, Morgan Territory67, Pleasanton Ridge28,67, Sunol28,67, Swanton Ranch63, UC Santa Cruz63 and Vasco Caves28,67. They vary with respect to climate, land use and disturbance history, soil type and relative cover of native species. Sites were classified as either annual valley grasslands, northern coastal prairies or serpentine grasslands based on soil type and location relative to the coast (Extended Data Table 1). Across sites, community composition sampling methods varied between point-intercept and aerial cover estimates in quadrats (Extended Data Table 1). Species abundance was measured as the relative contribution of species to the total intercepts or the cover in a quadrat for standardization across datasets. Data for most sites were collected once annually during peak spring growth. Most sites were dominated by non-native annual grass and forb species, except for sites on serpentine soils that were dominated by diverse native species (Extended Data Table 1). Extended Data Table 1 provides an overview of the locations, grass types and community data collection methods across all 12 sites.

Spanning large geographic and climatic gradients (Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 3), these 12 sites have experienced climate change. To quantify climate change that occurred within these observational grassland communities, we extracted past climate data from CHELSA68 and regressed annual temperature and precipitation over four decades. Similar to the overall trends in the CFP (Extended Data Fig. 1), the climatic trends in the 12 sites were warming (temperature increases) and drying (precipitation decreases) from 1980 to 2019, although the trends differed between sites (Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We quantified overall trends in mean annual temperature (MAT) and total annual precipitation (TAP) across the 12 sites with the following linear mixed-effects model to account for correlation between and within sites.

where s is the site of observation (one of the 12 sites), t is the time of observation (year), i is the plot (within sites) and β1 is the estimated overall rate of change (°C yr−1). A similar model applies to TAPsti. Overall, the 12 sites experienced climate warming of 0.0177 ± 0.00260 °C yr−1 (mean ± s.e.) and climate drying of −4.22 ± 1.48 mm yr−1.

The warming experiment was part of the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment (JRGCE) located in San Mateo, California (37° 24′ N, 122° 14.5′ W). The site occupies ~7,500 m2 within a 50,000 m2 stand of California annual and perennial valley grassland and has a Mediterranean climate with cool, wet winters and warm, dry summers. The experimental treatments consisted of four global change factors—temperature, precipitation, CO2 and nitrogen—at either ambient or an elevated level, applied in a complete factorial, randomized block design with eight replicates. Thirty-six circular plots 2 m in diameter, subdivided into 4 equal-sized subplots, were established in the summer of 1997. The 1997‒1998 growing season was a pretreatment year, after which treatments were applied for 16 consecutive growing seasons (1999‒2014), from the time of germination (November) to plant senescence (June).

Here we focus on the warming treatment, which was applied via heaters suspended above the circular plots. The warming treatment was implemented progressively with three phases. During phase 1 (1999‒2002), the heating was applied at +80 W m−2, resulting in an approximate temperature warming of +1 °C. Subsequently, in phase 2 (2003‒2009), the heating was increased to +100 W m−2, leading to a temperature warming of around +1.5 °C. Finally, in phase 3 (2010‒2014), the heating was more than doubled in strength to +250 W m−2, which was approximately equivalent to a temperature warming of +2 °C (ref. 42). We leveraged the full-factorial design and pooled subplots with treatments other than warming in a balanced manner to arrive at 72 ambient subplots and 64 warming subplots. The grassland community composition was measured using a similar point-intercept method, by lowering pins into the vegetation at fixed grid locations and recording the number and species of all plants that hit the pin69.

Additional watering and drought experiments

In the main analysis, we focus on the effect of the warming treatment in the JRGCE. Here we provide more information on the additional treatments and experiments that were designed to study the effect of changes in precipitation and drought. In the JRGCE, the watering treatment imposed was +50% of ambient rainfall, plus two 10 mm additions after the last rainfall event42, giving rise to 72 ambient plots and 64 watering plots.

The effects of both watering and drought were examined in the McLaughlin Water Experiment located at the University of California McLaughlin Reserve (38° 52′ N, 122° 26′ W) from 2015 to 2021 (missing data in 2020)70. For the watering sub-experiment, horizontal watering lines were laid out to water 30 serpentine plots and 10 total non-serpentine plots, with equal numbers of unwatered control plots. From 1 December to 1 March of each year, sprinklers were operated weekly to bring total (natural plus supplemental) precipitation up to or slightly above the 30 year weekly average. For the drought sub-experiment, rainfall shelters (3 × 3 m) that intercepted 100% of precipitation were installed at 10 plots on deep serpentine soils, with 10 unsheltered control plots. The shelters in place from 1 December to 1 March of each year were designed to exclude roughly 70% of annual precipitation, simulating an ‘extreme’ drought scenario, although the shelters did not completely exclude precipitation. Each year, a 1 × 1 m ‘core’ plot in each plot was sampled for species-specific aerial cover.

The effect of drought was also examined at three sites in the Santa Cruz International Drought Experiment from 2015 to 2021 (missing data in 2020)71. The experiment was conducted at three sites near UC Santa Cruz (36° 59′ N, 122° 3′ W), namely Arboretum, Marshall Field and Younger Lagoon. Rainfall interception shelters (4 × 4 m) with V‐shaped troughs were installed to intercept 60% of ambient precipitation and to divert the water off plots72. Each site had five drought treatment plots and five control plots. Research plots occupying the central 2 × 2 m of shelters were sampled each year for species-specific aerial cover.

Taxonomic harmonization

The grassland community data inevitably contain taxonomic nomenclature issues. Following the general guidelines and best-practice principles73, we harmonized taxon names in two steps. First, we corrected misspelled species names by preparing a taxonomic table with unique species names and guilds from observational and experimental community data. The taxonomic table was first automatically informed by the R package taxize74 and then manually compiled by two independent taxonomic experts on the author team (J.C. Lesage and J.C. Luong). Second, we consolidated the obsolete species names, subspecies and varieties to up-to-date, consistent, synonym-resolved species names, according to the current taxonomy by the same two experts using the California Jepson eFlora75.

All taxonomic groups were identified at the species level, with exceptions in the genera Avena, Festuca and Hypochaeris. In these genera, some records were identified only at the genus level. To maximize sample size and minimize bias, we retained these unidentified records and assigned dummy species to these three records. The climatic niche of the dummy species was estimated by averaging over all the species in their corresponding genus. Specifically, the Avena dummy species were the average of Avena barbata and Avena fatua, the Festuca dummy species were the average of Festuca bromoides and Festuca perennis, and the Hypochaeris dummy species were the average of Hypochaeris glabra and H. radicata.

In total, we identified 372 consolidated species (excluding dummies and including 110 non-native species) across the observational and experimental grassland communities. These species were used for the subsequent analyses.

Species occurrence and climatic niche estimation

We retrieved species’ geographical distributions from observed occurrence records and quantified their niches from climate data. Specifically, we first downloaded all the georeferenced plant location records publicly available through the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) in the CFP on 2 August 202376. We downloaded records of not only the consolidated species but also their synonyms, identified by two independent taxonomic experts on the author team (J.C. Lesage and J.C. Luong). We filtered for GBIF records with coordinates and with no known geospatial issues, including exactly zero coordinates, coordinates outside of the given country’s polygon, uninterpretable coordinates and out-of-range coordinates. We further filtered for records with valid coordinate uncertainty below 10 km and removed duplicate records. We obtained 830,175 records for 369 species. To ensure that niche estimates are of high quality, we retained species with more than 100 occurrences recorded in the GBIF data. In total, we retained 829,337 records for 349 species (including 239,797 records for 104 non-native species).

The relationship between species’ ecological niches and geographic distributions in the CFP77 allows us to assess climate change impacts on community composition by tracking communities in the niche space. To estimate species’ climatic niches, we then obtained long-term average climate data to quantify species niche centroids as the median temperature and precipitation across all occurrences of the species. We chose the median to summarize central tendency because it is a robust statistic, which does not assume normal distribution and is not unduly affected by outliers. Specifically, we obtained climatology data from CHELSA for 1981‒201068. We show species’ niche estimation with the two examples corresponding to Fig. 1, D. californica (Extended Data Fig. 4) and S. pulchra (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Community compositional shift analysis

We calculated the community-weighted means (CWM) of the temperature and precipitation niche centroids (species niche centroids). We referred to these two CWMs as the CTI and the CPI, respectively. Assigning CTI and CPI to communities weighted by species abundances is equivalent to the method of moments in statistical inference.

Indices such as CTI and CPI are straightforward measures of the relative dominance of species associated with certain temperature and precipitation levels, based on historical climate averages and species occurrence records. Such indices have been extensively used to test the prediction of directional compositional changes in a variety of communities, including animals6,78,79, plants5,7 and multi-taxon communities15. For plants, analyses of resurveyed forest plots in the tropics suggest that thermophilization lags behind climatic warming for long-lived trees12, consistent with slow tree migration in the temperate zones8,9. However, it remains unclear how climate change drives CTI–CPI changes in grasslands, where shorter lifespans promote faster population turnover and might facilitate more rapid community compositional shifts in response to climate change.

For site s, year t, plot i and species j, species abundance (point intercept or percentage cover) is denoted as Astij, the temperature niche centroid as Tj and the precipitation niche centroid as Pj. Across all the species j = 1, …, J, the CWM of temperature, that is, CTI, is the first moment, or the expected community temperature under the species abundance distribution:

Likewise, the CWM of precipitation, that is, CPI, is the expected community precipitation under the species’ abundance distribution:

A higher CTI suggests that species associated with warmer locations are more prevalent and abundant in the community; likewise, a lower CPI suggests that species associated with drier locations are more prevalent and abundant in the community22.

For the observational communities, we compared CTI and CPI across years, quantifying the rate of thermophilization and xerophilization. While simple linear regression provides a straightforward way to characterize site-specific trends, we quantified overall trends in CTI and CPI with linear mixed-effects models, to account for spatial correlation between sites and temporal autocorrelation within sites.

where s is the site of observation (one of the 12 sites), t is the time of observation (year), i is the plot (within sites) and β1 is the estimated overall rate of change (°C yr−1). A similar model applies to CPIsti. The use of random intercepts (b0s) and random slopes (b1s) accounts for spatial correlation in compositional changes. Annual grassland communities are highly independent of years, as shown in previous studies42, partly driven by the summer dieback of Mediterranean grasslands48. Nevertheless, our use of random intercepts and random slopes further alleviates possible issues from temporal autocorrelation. We also summarized site-specific CTI and CPI change over the years by linear regression (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

For the experimental communities, similar to observations, we quantified the overall effects of experimental treatments on CTI and CPI using linear mixed-effects models, pooling data from all years in an experiment, with the consideration of temporal correlation (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 7).

where t is the time of experimental treatment (year), i is the plot, xi is the experimental treatment of the plot (0 = control group, 1 = treatment group) and β1 is the estimated treatment effect (°C). Likewise, a similar model applies to CPIti. The use of random intercepts (b0t) accounts for variations and correlations between years. We also compared CTI and CPI between ambient and warming treatments each year using linear regressions with CTI or CPI as the response variable and treatment as the predictor.

Similar to the analyses for the warming treatment, we used linear mixed-effects models to test the effects of watering and drought in additional experiments. For JRGCE, we also tested the effects of watering treatment on CTI and CPI (equation (5), Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 7). For the McLaughlin Water Experiment, we tested the effects of watering on CTI and CPI in both serpentine and non-serpentine communities (equation (5), Extended Data Fig. 7a,b and Supplementary Table 7). The effects of drought were tested similarly in the serpentine community (equation (5); drought treatment was not available for the non-serpentine community) (Extended Data Fig. 7c and Supplementary Table 7). For the Santa Cruz International Drought Experiment, the effects of drought on CTI and CPI were tested at three sites (Arboretum, Marshall Field and Younger Lagoon), respectively (equation (5), Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 7). We visualized and compared the effects of global change manipulations in three experiments (Extended Data Fig. 9).

When fitting linear mixed-effects models, we used two-sided t-tests to test whether slope parameters β1 were significantly different from zero and concluded significance when P ≤ 0.05. We used communities defined by distinct combinations of plot and year as units of analysis. Plots within a site are biological replicates. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons, as we performed each test for an independent set of observations or an independent experiment.

Analysis and synthesis of community shifts

We examined responses at the species level that underlie community-level responses. We identified the species that increased or decreased in abundance over time at each observational site, especially those that established in the community (appeared after the first 5 years) or extirpated from the community (disappeared in the last 5 years) (Supplementary Fig. 16)21. A similar comparison was conducted for the experiment, by identifying the species that increased or decreased in abundance in the warming treatment compared with the ambient treatment (Supplementary Fig. 17). We compared the temperature and precipitation niche centroid among species that increased, decreased or had no change in abundance under climate change using the two-sided Wilcoxon test, robust to outliers in species’ niche centroid (Fig. 4c,d). To explore whether community compositional shifts were driven by dominant or rare species, we further compared the rank abundance curves over time at observational sites (Supplementary Fig. 18) and between ambient and warming treatments in the experiment (Supplementary Fig. 19). We compared the evenness of communities measured by Pielou’s evenness J over time (linear regression, two-sided t-test) or between treatments (two-sided Wilcoxon test, P ≤ 0.05).

We synthesized community compositional shifts from long-term observations across the 12 sites and the JRGCE warming experiment in the climate niche space (Fig. 5). We visualized and quantified the change in CPI relative to the change in CTI and vice versa for both observational and experimental data.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The grassland community composition dataset that supports the findings of this study is publicly available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13750955 (ref. 80). The occurrence data were retrieved from GBIF, the climatic variables at occurrence locations were retrieved from CHELSA and intermediate datasets are also available in the same folder.

Code availability

All the computational analyses were performed in R 4.2.0 (ref. 81). The fully reproducible workflow, including code and processed data, is in the form of an R package and publicly available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13750955 (ref. 80).

References

Chen, I.-C., Hill, J. K., Ohlemüller, R., Roy, D. B. & Thomas, C. D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 333, 1024–1026 (2011).

Corlett, R. T. & Westcott, D. A. Will plant movements keep up with climate change? Trends Ecol. Evol. 28, 482–488 (2013).

Lawlor, J. A. et al. Mechanisms, detection and impacts of species redistributions under climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 351–368 (2024).

Loarie, S. R. et al. The velocity of climate change. Nature 462, 1052–1055 (2009).

Bertrand, R. et al. Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests. Nature 479, 517–520 (2011).

Devictor, V. et al. Differences in the climatic debts of birds and butterflies at a continental scale. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 121–124 (2012).

Gottfried, M. et al. Continent-wide response of mountain vegetation to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 111–115 (2012).

Zhu, K., Woodall, C. W. & Clark, J. S. Failure to migrate: lack of tree range expansion in response to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 1042–1052 (2012).

Zhu, K., Woodall, C. W., Ghosh, S., Gelfand, A. E. & Clark, J. S. Dual impacts of climate change: forest migration and turnover through life history. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 251–264 (2014).

Duque, A., Stevenson, P. R. & Feeley, K. J. Thermophilization of adult and juvenile tree communities in the northern tropical Andes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10744–10749 (2015).

Bertrand, R. et al. Ecological constraints increase the climatic debt in forests. Nat. Commun. 7, 12643 (2016).

Fadrique, B. et al. Widespread but heterogeneous responses of Andean forests to climate change. Nature 564, 207–212 (2018).

Lenoir, J. et al. Species better track climate warming in the oceans than on land. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1044–1059 (2020).

Zellweger, F. et al. Forest microclimate dynamics drive plant responses to warming. Science 368, 772 (2020).

Freeman, B. G., Song, Y., Feeley, K. J. & Zhu, K. Montane species track rising temperatures better in the tropics than in the temperate zone. Ecol. Lett. 24, 1697–1708 (2021).

Richard, B. et al. The climatic debt is growing in the understorey of temperate forests: stand characteristics matter. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 1474–1487 (2021).

Loik, M. E. Press, pulse, and squeeze: is climatic equilibrium ever possible on mountains? Biol. Conserv. 291, 110468 (2024).

Cleland, E. E. et al. Sensitivity of grassland plant community composition to spatial vs. temporal variation in precipitation. Ecology 94, 1687–1696 (2013).

Lenoir, J. & Svenning, J.-C. Climate-related range shifts—a global multidimensional synthesis and new research directions. Ecography 38, 15–28 (2015).

Jarzyna, M. A., Zuckerberg, B., Finley, A. O. & Porter, W. F. Synergistic effects of climate and land cover: grassland birds are more vulnerable to climate change. Landsc. Ecol. 31, 2275–2290 (2016).

Maclean, I. M. D. & Early, R. Macroclimate data overestimate range shifts of plants in response to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 484–490 (2023).

Feeley, K. J., Bravo-Avila, C., Fadrique, B., Perez, T. M. & Zuleta, D. Climate-driven changes in the composition of New World plant communities. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 965–970 (2020).

Hoover, D. L., Knapp, A. K. & Smith, M. D. Resistance and resilience of a grassland ecosystem to climate extremes. Ecology 95, 2646–2656 (2014).

Harrison, S. P., Gornish, E. S. & Copeland, S. Climate-driven diversity loss in a grassland community. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 8672–8677 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. Shifting plant species composition in response to climate change stabilizes grassland primary production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4051–4056 (2018).

Zavaleta, E. S. et al. Grassland responses to three years of elevated temperature, CO2, precipitation, and N deposition. Ecol. Monogr. 73, 585–604 (2003).

Harpole, W. S., Potts, D. L. & Suding, K. N. Ecosystem responses to water and nitrogen amendment in a California grassland. Glob. Change Biol. 13, 2341–2348 (2007).

Dudney, J. et al. Lagging behind: have we overlooked previous-year rainfall effects in annual grasslands? J. Ecol. 105, 484–495 (2017).

Griffin-Nolan, R. J. et al. Shifts in plant functional composition following long-term drought in grasslands. J. Ecol. 107, 2133–2148 (2019).

Hoffman, M., Koenig, K., Bunting, G., Costanza, J. & Williams, K. J. Biodiversity hotspots (version 2016.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3261807 (2016).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000).

Burge, D. O. et al. Plant diversity and endemism in the California Floristic Province. Madroño 63, 3–206 (2016).

Stromberg, M. R., Kephart, P. & Yadon, V. Composition, invasibility, and diversity in coastal California grasslands. Madroño 48, 236–252 (2001).

Vasey, M. C., Loik, M. E. & Parker, V. T. Influence of summer marine fog and low cloud stratus on water relations of evergreen woody shrubs (Arctostaphylos: Ericaceae) in the chaparral of central California. Oecologia 170, 325–337 (2012).

De Frenne, P. et al. Microclimate moderates plant responses to macroclimate warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18561–18565 (2013).

Ackerly, D. D. et al. Topoclimates, refugia, and biotic responses to climate change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 18, 288–297 (2020).

Going, B. M., Hillerislambers, J. & Levine, J. M. Abiotic and biotic resistance to grass invasion in serpentine annual plant communities. Oecologia 159, 839–847 (2009).

Harrison, S., Damschen, E., Fernandez-Going, B., Eskelinen, A. & Copeland, S. Plant communities on infertile soils are less sensitive to climate change. Ann. Bot. 116, 1017–1022 (2015).

Willis, C. G. et al. Favorable climate change response explains non-native species’ success in Thoreau’s woods. PLoS ONE 5, e8878 (2010).

Sorte, C. J. B. et al. Poised to prosper? A cross-system comparison of climate change effects on native and non-native species performance. Ecol. Lett. 16, 261–270 (2013).

Dainese, M. et al. Human disturbance and upward expansion of plants in a warming climate. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 577–580 (2017).

Zhu, K., Chiariello, N. R., Tobeck, T., Fukami, T. & Field, C. B. Nonlinear, interacting responses to climate limit grassland production under global change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10589–10594 (2016).

Smith, M. D. et al. Extreme drought impacts have been underestimated in grasslands and shrublands globally. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2309881120 (2024).

Bowler, D. E. et al. Cross-realm assessment of climate change impacts on species’ abundance trends. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0067 (2017).

Dee, L. E. et al. Clarifying the effect of biodiversity on productivity in natural ecosystems with longitudinal data and methods for causal inference. Nat. Commun. 14, 2607 (2023).

Rosenblad, K. C., Baer, K. C. & Ackerly, D. D. Climate change, tree demography, and thermophilization in western US forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2301754120 (2023).

Cuesta, F. et al. Compositional shifts of alpine plant communities across the high Andes. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32, 1591–1606 (2023).

Balachowski, J. A., Bristiel, P. M. & Volaire, F. A. Summer dormancy, drought survival and functional resource acquisition strategies in California perennial grasses. Ann. Bot. 118, 357–368 (2016).

Maclean, I. M. D., Hopkins, J. J., Bennie, J., Lawson, C. R. & Wilson, R. J. Microclimates buffer the responses of plant communities to climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 24, 1340–1350 (2015).

De Frenne, P. et al. Forest microclimates and climate change: importance, drivers and future research agenda. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 2279–2297 (2021).

Bradley, B. A. et al. Observed and potential range shifts of native and nonnative species with climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 55 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102722-013135 (2024).

Wessely, J. et al. A climate-induced tree species bottleneck for forest management in Europe. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1109–1117 (2024).

Bestion, E., Clobert, J. & Cote, J. Dispersal response to climate change: scaling down to intraspecific variation. Ecol. Lett. 18, 1226–1233 (2015).

Wasof, S. et al. Disjunct populations of European vascular plant species keep the same climatic niches. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 24, 1401–1412 (2015).

Mooney, H. & Zavaleta, E. Ecosystems of California (University of California Press, 2016).

Harte, J. & Shaw, R. Shifting dominance within a montane vegetation community: results of a climate-warming experiment. Science 267, 876–880 (1995).

Li, D., Miller, J. E. D. & Harrison, S. Climate drives loss of phylogenetic diversity in a grassland community. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19989–19994 (2019).

Harrison, S. Plant community diversity will decline more than increase under climatic warming. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190106 (2020).

Harrison, S., Spasojevic, M. J. & Li, D. Climate and plant community diversity in space and time. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 4464–4470 (2020).

Friedl, M. & Sulla-Menashe, D. MCD12C1 MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 0.05Deg CMG V006. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12C1.006 (2022).

Suttle, K. B. & Thomsen, M. A. Climate change and grassland restoration in California: lessons from six years of rainfall manipulation in a north coast grassland. Madroño 54, 225–233 (2007).

Grinath, J. B., Larios, L., Prugh, L. R., Brashares, J. S. & Suding, K. N. Environmental gradients determine the potential for ecosystem engineering effects. Oikos 128, 994–1004 (2019).

Hayes, G. F. & Holl, K. D. Manipulating disturbance regimes and seeding to restore mesic Mediterranean grasslands. Appl. Veg. Sci. 14, 304–315 (2011).

Hobbs, R. J. & Mooney, H. A. Community and population dynamics of serpentine grassland annuals in relation to gopher disturbance. Oecologia 67, 342–351 (1985).

Hobbs, R. J. & Mooney, H. A. Effects of rainfall variability and gopher disturbance on serpentine annual grassland dynamics. Ecology 72, 59–68 (1991).

Fernandez-Going, B. M., Anacker, B. L. & Harrison, S. P. Temporal variability in California grasslands: soil type and species functional traits mediate response to precipitation. Ecology 93, 2104–2114 (2012).

Gennet, S., Spotswood, E., Hammond, M. & Bartolome, J. W. Livestock grazing supports native plants and songbirds in a California annual grassland. PLoS ONE 12, e0176367 (2017).

Karger, D. N. et al. Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Sci. Data 4, 170122 (2017).

Andresen, L. C. et al. in Advances in Ecological Research Vol. 55 (eds Dumbrell, A. J. et al.) 437–473 (Academic Press, 2016).

Harrison, S. P., LaForgia, M. L. & Latimer, A. M. Climate‐driven diversity change in annual grasslands: drought plus deluge does not equal normal. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 1782–1792 (2018).

Loik, M. E., Lesage, J. C., Brown, T. M. & Hastings, D. O. Drought-Net rainfall shelters did not cause nondrought effects on photosynthesis for California central coast plants. Ecohydrology 12, e2138 (2019).

Yahdjian, L. & Sala, O. E. A rainout shelter design for intercepting different amounts of rainfall. Oecologia 133, 95–101 (2002).

Grenié, M. et al. Harmonizing taxon names in biodiversity data: a review of tools, databases and best practices. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 12–25 (2023).

Chamberlain, S. A., & Szöcs, E. taxize: taxonomic search and retrieval in R. F1000Research 2, 191 (2013); https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.2-191.v2

Jepson Flora Project Jepson eFlora (University of California Press, 2022).

Derived dataset GBIF.org. Filtered export of GBIF occurrence data. https://doi.org/10.15468/dd.f8sdry (2024).

Rose, M. B., Velazco, S. J. E., Regan, H. M. & Franklin, J. Rarity, geography, and plant exposure to global change in the California Floristic Province. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32, 218–232 (2023).

Cheung, W. W. L., Watson, R. & Pauly, D. Signature of ocean warming in global fisheries catch. Nature 497, 365–368 (2013).

Soroye, P., Newbold, T. & Kerr, J. Climate change contributes to widespread declines among bumble bees across continents. Science 367, 685–688 (2020).

Song, Y. & Zhu, K. zhulabgroup/grassland-cfp: publication. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13750955 (2024).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023); https://www.R-project.org/

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Ibáñez, P. B. Reich, N. J. Sanders, B. C. Weeks, M. N. Umaña, D. R. Zak and members of the University of Michigan Institute for Global Change Biology and Zhu Lab for constructive comments. We thank Y. Chen and K. Shedden for the statistical consulting. K.Z. and Y.S. were supported by the US National Science Foundation grants 2244711 and 2306198. Y.S. was supported by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Schmidt Sciences programme. Data collection at Pleasanton Ridge, Sunol and Vasco Caves by J.W.B., M.H. and P.H. was funded by the East Bay Regional Park District. The Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment was supported by the US National Science Foundation (grants 9727059, 0221838 and 0918617 to C.B.F.), US Department of Energy, Packard Foundation, Morgan Family Foundation, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Stanford University and Carnegie Institution for Science. L.M.H. acknowledges funding from the US National Science Foundation grant 2047239. G.F.H. and K.D.H. acknowledge funding from the US Department of Agriculture grant 99-35101-8234. R.J.H. was supported by a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) postdoctoral fellowship during data collection at the Jasper Ridge serpentine site. L.M.H. and R.J.H. received subsequent funding from the National Science Foundation, Mellon Foundation, CSIRO, Murdoch University and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions. L.L. acknowledges funding from the US Department of Agriculture Hatch Fund award CA-R-BPS-5212-H. L.R.P. acknowledges funding from the US National Science Foundation grant 1628754.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z. and Y.S. conceived the project. Data curation was carried out by Y.S., J.C. Lesage, J.C. Luong, J.W.B., N.R.C., J.D., C.B.F., L.M.H., M.H., S.P.H., G.F.H., R.J.H., K.D.H., P.H., L.L., M.E.L. and L.R.P. The methodology was developed by K.Z., Y.S., J. C. Lesage and J. C. Luong. K.Z. and Y.S. wrote the original draft, and all authors reviewed and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Jonathan Lenoir and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Climate change in the California Floristic Province (CFP).

Linear regressions describe trends in (A) mean annual temperature (°C yr−1) and (B) annual precipitation (mm yr−1) over the years, from 1980 to 2019, in 30 arc sec ( ~ 1 km) resolution, estimated from the CHELSA time series data. Contour lines surround pixels with statistically significant trends (two-sided t-test, p ≤ 0.05).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Data availability of 12 observational sites and three global change experiments.

The green lines indicate the start and the end of sampling; the black dots show the years in which sampling was conducted; the size of the black dots shows the sample size (number of treatment plots or number of observational plots per year).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Climate change at the observational sites.

Mean annual temperature (°C) and annual precipitation (mm) are extracted from the CHELSA monthly time series from 1980 to 2019, highlighting the sampling periods in the observational periods for comparison with Fig. 2. Trends are summarized by regression lines, solid p ≤ 0.05, dashed p > 0.05 (two-sided t-test; ns: p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001). The map shows the geographical distribution of the 12 sites with grassland percent cover (green) from MODIS land cover type data.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Example species Danthonia californica’s distributions in geographical space and climate space.

The left shows GBIF occurrence records in the CFP. The right panel shows the number of GBIF records (n) and their distribution in reference to mean annual temperature and precipitation from CHELSA data. The scatters are summarized by axis rugs for marginal distributions, as well as a Gaussian data ellipse at the 95% confidence interval and a centroid cross (median) for the joint distribution.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Example species Stipa pulchra’s distributions in geographical space and climate space.

The left shows GBIF occurrence records in the CFP. The right panel shows the number of GBIF records (n) and their distribution in reference to mean annual temperature and precipitation from CHELSA data. The scatters are summarized by axis rugs for marginal distributions, as well as a Gaussian data ellipse at the 95% confidence interval and a centroid cross (median) for the joint distribution.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Effect of watering treatment in the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment.

Watering treatment generally decreased CTI (°C) and increased CPI (mm). Ambient plots (n = 72) and watering plots (n = 64) are shown in black and blue, respectively. Effects across all years were estimated by linear mixed-effects models (two-sided t-test; ns: p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001). Box plots show the median (center), the first and third quartiles (bounds of the box), the range extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles (whiskers), and outliers beyond this range (points).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Effect of watering and drought treatments in the McLaughlin Water Experiment on CTI (°C) and CPI (mm).

Watering experiments were conducted in both (A) serpentine and (B) non-serpentine sites, while drought experiment was conducted in (C) the serpentine site. Ambient plots, watering plots, and drought plots are in black, blue, and brown, respectively. There were 30 ambient and 30 treatment plots in (A). There were ten ambient and ten treatment plots in (B) and (C). Effects across all years were estimated by linear mixed-effects models (two-sided t-test; ns: p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001). Box plots show the median (center), the first and third quartiles (bounds of the box), the range extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles (whiskers), and outliers beyond this range (points).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Effect of drought treatment on CTI (°C) and CPI (mm) in the Santa Cruz International Drought Experiment.

Experiments were conducted at three sites: (A) Arboretum (10 ambient plots and 8 treatment plots), (B) Marshall Field (9 ambient plots and 9 treatment plots), and (C) Younger Lagoon (5 ambient plots and 5 treatment plots). Ambient plots and drought plots are shown in black and brown, respectively. Effects across all years were estimated by linear mixed-effects models (two-sided t-test; ns: p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001). Box plots show the median (center), the first and third quartiles (bounds of the box), the range extending to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles (whiskers), and outliers beyond this range (points).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Effect size of manipulations on CTI (°C) and decreased CPI (mm) in three global change experiment projects.

JRGCE: Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment; MWE: McLaughlin Water Experiment; SCIDE: Santa Cruz International Drought Experiment. Different phases, soil types, and sites in a project were considered to constitute different experiments. Effect sizes were estimated across years in each experiment by linear mixed-effects models (two-sided t-test; ns: p > 0.05, sig: p ≤ 0.05). We show the mean estimates (points) and 1.95 standard errors (error bars).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–19, Tables 1–7 and Notes 1–4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, K., Song, Y., Lesage, J.C. et al. Rapid shifts in grassland communities driven by climate change. Nat Ecol Evol 8, 2252–2264 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02552-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02552-z

This article is cited by

-

Shifts in precipitation regimes exacerbate global inequality in grassland nitrogen cycles

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Divergent resource limitations of belowground versus aboveground productivity across grasslands

Nature Communications (2025)

-

A new lens on drought impacts: unlocking continental contrasts in grassland sensitivity

Science China Life Sciences (2025)

-

Precipitation pattern changes in Northern China before and after the weakening of the Asian summer monsoon

Climate Dynamics (2025)

-

Long-term and short-term effects of nitrogen addition on soil acidification in a temperate steppe

Plant and Soil (2025)