Abstract

Spin–orbit coupling (SOC) has played an important role in many topological and correlated electron materials. In graphene-based systems, SOC induced by a transition metal dichalcogenide at close proximity has been shown to drive topological states and strengthen superconductivity. However, in rhombohedral multilayer graphene, a robust platform for electron correlation and topology, superconductivity and the role of SOC remain largely unexplored. Here we report transport measurements of transition metal dichalcogenide-proximitized rhombohedral trilayer graphene. We observed a hole-doped superconducting state SC4 with a critical temperature of 234 mK. On the electron-doped side, we noted an isospin-symmetry-breaking three-quarter-metal phase and observed that the nearby weak superconducting state SC3 is substantially enhanced. Surprisingly, the original superconducting state SC1 in bare rhombohedral trilayer graphene is strongly suppressed in the presence of transition metal dichalcogenide—opposite to the effect of SOC on all other graphene superconductivities. Our observations form the basis of exploring superconductivity and non-Abelian quasiparticles in rhombohedral graphene devices.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data shown in the main figures are available via the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JTUM2H (ref. 63). The datasets generated during and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used to calculate Fig. 3i is available via the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JTUM2H (ref. 63).

References

Han, T. et al. Large quantum anomalous Hall effect in spin-orbit proximitized rhombohedral graphene. Science 384, 647–651 (2024).

Lu, Z. et al. Fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect in multilayer graphene. Nature 626, 759–764 (2024).

Chen, G. et al. Evidence of a gate-tunable Mott insulator in a trilayer graphene moiré superlattice. Nat. Phys. 15, 237–241 (2019).

Zhou, H. et al. Half- and quarter-metals in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nature 598, 429–433 (2021).

Zhou, H., Xie, T., Taniguchi, T., Watanabe, K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nature 598, 434–438 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Spectroscopy signatures of electron correlations in a trilayer graphene/hBN moiré superlattice. Science 375, 1295–1299 (2022).

Han, T. et al. Correlated insulator and Chern insulators in pentalayer rhombohedral-stacked graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 181–187 (2024).

Han, T. et al. Orbital multiferroicity in pentalayer rhombohedral graphene. Nature 623, 41–47 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. Spontaneous broken-symmetry insulator and metals in tetralayer rhombohedral graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 188–195 (2024).

Winterer, F. et al. Ferroelectric and spontaneous quantum Hall states in intrinsic rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 20, 422–427 (2024).

Arp, T. et al. Intervalley coherence and intrinsic spin-orbit coupling in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys 20, 1413–1420 (2024).

Zhang, F., Sahu, B., Min, H. & MacDonald, A. H. Band structure of ABC-stacked graphene trilayers. Phys. Rev. B 82, 035409 (2010).

Jung, J., Zhang, F. & MacDonald, A. H. Lattice theory of pseudospin ferromagnetism in bilayer graphene: competing interaction-induced quantum Hall states. Phys. Rev. B 83, 115408 (2011).

Reddy, A. P., Paul, N., Abouelkomsan, A. & Fu, L. Non-Abelian fractionalization in topological minibands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 166503 (2024).

Ju, L., MacDonald, A. H., Mak, K. F., Shan, J. & Xu, X. The fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 455–459 (2024).

Zhou, H. et al. Isospin magnetism and spin-polarized superconductivity in Bernal bilayer graphene. Science 375, 774–778 (2022).

Zhou, H. Ferromagnetism and Superconductivity in Rhombohedral Trilayer Graphene. PhD thesis, UC Santa Barbara (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Enhanced superconductivity in spin–orbit proximitized bilayer graphene. Nature 613, 268–273 (2023).

Holleis, L. et al. Nematicity and orbital depairing in superconducting Bernal bilayer graphene with strong spin orbit coupling. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.00742 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Twist-programmable superconductivity in spin–orbit coupled bilayer graphene. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.10335 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Tunable superconductivity in electron- and hole-doped Bernal bilayer graphene. Nature 631, 300–306 (2024).

Arora, H. S. et al. Superconductivity in metallic twisted bilayer graphene stabilized by WSe2. Nature 583, 379–384 (2020).

Su, R., Kuiri, M., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Folk, J. Superconductivity in twisted double bilayer graphene stabilized by WSe2. Nat. Mater. 22, 1332–1337 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Promotion of superconductivity in magic-angle graphene multilayers. Science 377, 1538–1543 (2022).

Lu, J. M. et al. Evidence for two-dimensional Ising superconductivity in gated MoS2. Science 350, 1353–1357 (2015).

Saito, Y. et al. Superconductivity protected by spin–valley locking in ion-gated MoS2. Nat. Phys. 12, 144–149 (2016).

Xi, X. et al. Ising pairing in superconducting NbSe2 atomic layers. Nat. Phys. 12, 139–143 (2016).

Island, J. O. et al. Spin–orbit-driven band inversion in bilayer graphene by the van der Waals proximity effect. Nature 571, 85–89 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Quantum Hall effect measurement of spin–orbit coupling strengths in ultraclean bilayer graphene/WSe2 heterostructures. Nano Lett. 19, 7028–7034 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Spin–orbit coupling and interactions in quantum Hall states of graphene/WSe2 heterobilayers. Phys. Rev. B 104, L201301 (2021).

Lin, J.-X. et al. Spin–orbit-driven ferromagnetism at half moiré filling in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Science 375, 437–441 (2022).

Wakamura, T. et al. Spin–orbit interaction induced in graphene by transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 99, 245402 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Strong interface-induced spin–orbit interaction in graphene on WS2. Nat. Commun. 6, 8339 (2015).

de la Barrera, S. C. et al. Cascade of isospin phase transitions in Bernal-stacked bilayer graphene at zero magnetic field. Nat. Phys. 18, 771–775 (2022).

Cao, Y. et al. Nematicity and competing orders in superconducting magic-angle graphene. Science 372, 264–271 (2021).

Koshino, M. & McCann, E. Trigonal warping and Berry’s phase Nπ in ABC-stacked multilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 165409 (2009).

Zollner, K., João, S. M., Nikolić, B. K. & Fabian, J. Twist- and gate-tunable proximity spin–orbit coupling, spin relaxation anisotropy, and charge-to-spin conversion in heterostructures of graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 108, 235166 (2023).

Li, Y. & Koshino, M. Twist-angle dependence of the proximity spin–orbit coupling in graphene on transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 99, 075438 (2019).

Zollner, K., Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Proximity spin–orbit and exchange coupling in ABA and ABC trilayer graphene van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 105, 115126 (2022).

Xie, M. & Das Sarma, S. Flavor symmetry breaking in spin–orbit coupled bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 107, L201119 (2023).

Dong, Z., Lantagne-Hurtubise, É. & Alicea, J. Superconductivity from spin-canting fluctuations in rhombohedral graphene. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17036 (2024).

Chou, Y.-Z., Wu, F. & Das Sarma, S. Enhanced superconductivity through virtual tunneling in Bernal bilayer graphene coupled to WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 106, L180502 (2022).

Dong, Z., Chubukov, A. V. & Levitov, L. Transformer spin-triplet superconductivity at the onset of isospin order in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 107, 174512 (2023).

Chou, Y.-Z., Tan, Y., Wu, F. & Das Sarma, S. Topological flat bands, valley polarization, and interband superconductivity in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene with proximitized spin–orbit couplings. Phys. Rev. B 110, L041108 (2024).

Dong, Z., Levitov, L. & Chubukov, A. V. Superconductivity near spin and valley orders in graphene multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 108, 134503 (2023).

You, Y.-Z. & Vishwanath, A. Kohn–Luttinger superconductivity and intervalley coherence in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 105, 134524 (2022).

Chatterjee, S., Wang, T., Berg, E. & Zaletel, M. P. Inter-valley coherent order and isospin fluctuation mediated superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 13, 6013 (2022).

Cea, T., Pantaleón, P. A., Phong, V. T. & Guinea, F. Superconductivity from repulsive interactions in rhombohedral trilayer graphene: a Kohn–Luttinger-like mechanism. Phys. Rev. B 105, 075432 (2022).

Chou, Y.-Z., Wu, F., Sau, J. D. & Das Sarma, S. Acoustic-phonon-mediated superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 187001 (2021).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Josephson current and noise at a superconductor/quantum-spin-Hall-insulator/superconductor junction. Phys. Rev. B 79, 161408 (2009).

Zhang, F. & Kane, C. L. Time-reversal-invariant Z4 fractional Josephson effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 036401 (2014).

Orth, C. P., Tiwari, R. P., Meng, T. & Schmidt, T. L. Non-Abelian parafermions in time-reversal-invariant interacting helical systems. Phys. Rev. B 91, 081406 (2015).

Zaletel, M. P. & Khoo, J. Y. The gate-tunable strong and fragile topology of multilayer-graphene on a transition metal dichalcogenide. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.01294 (2019).

Zhang, F., Jung, J., Fiete, G. A., Niu, Q. & MacDonald, A. H. Spontaneous quantum Hall states in chirally stacked few-layer graphene systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 156801 (2011).

Han, T. et al. Accurate measurement of the gap of graphene/h-BN moiré superlattice through photocurrent spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 146402 (2021).

Min, H. et al. Intrinsic and Rashba spin–orbit interactions in graphene sheets. Phys. Rev. B 74, 165310 (2006).

Naimer, T., Zollner, K., Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Twist-angle dependent proximity induced spin–orbit coupling in graphene/transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 104, 195156 (2021).

Yang, B. et al. Strong electron–hole symmetric Rashba spin–orbit coupling in graphene/monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 96, 041409 (2017).

Amann, J. et al. Counterintuitive gate dependence of weak antilocalization in bilayer graphene/WSe2 heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 105, 115425 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Origin and magnitude of ‘designer’ spin–orbit interaction in graphene on semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. X 6, 041020 (2016).

Lui, C. H., Li, Z., Mak, K. F., Cappelluti, E. & Heinz, T. F. Observation of an electrically tunable band gap in trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 7, 944–947 (2011).

Velasco, J. Jr et al. Transport spectroscopy of symmetry-broken insulating states in bilayer graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 156–160 (2012).

Yang, J. & Yoon, C. Replication data for: Impact of spin–orbit coupling on superconductivity in rhombohedral graphene. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JTUM2H (2025).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge helpful discussions with T. Senthil, E. Berg, A. Stern, L. Levitov, Z. Dong, T. Wang and J. Alicea. We thank D. Zumbühl, A. Cotton, O. Sedeh, M. Xu, H. Weldeyesus, C. Scheller and Z. Hadjri for assistance in measurement during the revision process. L.J. acknowledges support from a Sloan Fellowship. J.Y. and J.S. were supported by NSF grant DMR-2414725. T.H. was supported by NSF grant DMR-2225925. The device fabrication for this work was carried out at the Harvard Center for Nanoscale Systems and MIT.nano. The data analysis and writing were supported by the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-004447252). K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (grants 20H00354, 21H05233 and 23H02052) and the World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan. C.Y. and F.Z. were supported by the NSF under grants DMR-2414726, DMR-1945351, DMR-2105139 and DMR-2324033; they also acknowledge the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) for providing resources that have contributed to the research results reported in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J. supervised the project. J.Y., X.S., Z.L. and V.K. performed the DC magneto-transport measurements. J.Y., S.Y., T.H. and L.S. fabricated the devices. J.S., Z.L. and T.H. helped with installing and testing the dilution refrigerator. K.W. and T.T. grew the hBN crystals. C.Y. and F.Z. performed the theoretical calculations. All authors discussed the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Superconductivity in a second device D2.

a, Four-terminal resistance Rxx as a function of n and D for device D2. Similar to D1, well-developed SC4 and SC3 can be observed in both D > 0 and D < 0 regime. Inset: optical image of the device. “S” and “D” stand for source and drain, and Rxx is measured from contact “1” / “2”. b, Illustration of sample structure. Different from D1, in D2 RTG is encapsulated by two bilayer tungsten diselenide (2L-WSe2). Thus, the top and bottom 2L-WSe2 are aligned in 0° with respect to each other to preserve the inversion symmetry. c, Differential resistance dV/dI as a function of the direct current IDC of SC4 and SC3, measured at the square and the circle markers in a.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Out-of-plane magnetic field dependence of critical current and the Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless transition.

a–d, Differential resistance dV/dI as a function of the direct current IDC and out-of-plane magnetic field B⊥, for D1 SC4 (a), D1 SC3 (b), D2 SC4 (c), and D2 SC3 (d). Fraunhofer oscillation patterns can be seen in D1 SC4 but not in other superconducting states. e, f, Voltage V as a function of direct current IDC at different temperature, for D1 SC4 (e) and D1 SC3 (f), measured at the green and orange marker positions in Fig. 1b. By comparing the data with V ~ I3 (grey dash lines), we can determine the Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless transition temperature TBKT is 173 mK for D1 SC4 and 85 mK for D1 SC3.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Temperature dependence of SC states in the single-side-TMD device D3.

a, c, Temperature dependence of SC1, when holes are in the top / bottom, proximitized to / far away from the TMD layer. e, Temperature dependence of SC4 for D > 0, corresponding to holes are close to the top TMD layer. g, i, Temperature dependence of SC3, when electrons are in the top / bottom, close to / far away from the TMD layer. b, d, f, h and j, Temperature dependence of dV/dIDC, corresponding to the superconducting states in a, c, e, g and i.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Temperature dependence of superconducting states in D2.

a, Rxx as a function of n and D near SC4 in D2. b, c, Temperature dependence of Rxx in SC4, measured at D = −0.20 V/nm and D = −0.17 V/nm. d, Rxx as a function of n and D near SC3 in D2. e–i, Temperature dependence of Rxx in SC4, measured from D = 0.14 V/nm to D = 0.26 V/nm, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Temperature dependence of SC4 in D2 at different in-plane magnetic field.

a–c, Temperature dependence of Rxx at B‖ = 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 T, respectively. d, Critical temperature Tc at n = −0.77 * 1012 cm−2, as a function of in-plane magnetic field B‖. Solid line is fitted with Tc/Tc,B=0 = 1 – B‖2/BSOBP, where the effective spin-orbit field BSO = λI/2gμB. Assuming g = 2, we can extract Ising-SOC intensity λI ~ 0.6 meV.

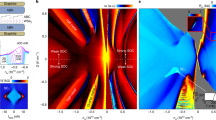

Extended Data Fig. 6 Detailed analysis of Fermiology near SC4 in D1.

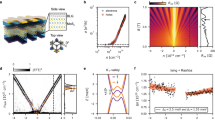

a, Four-terminal resistance Rxx of D1 near SC4. b, e, h, Rxx as a function of out-of-plane magnetic field B⊥, measured at the red dash lines in panel a: n = −0.76 × 1012 cm−2 (b), D = −0.2 V/nm (e), and D = −0.165 V/nm (h). c, f, i, Fourier transform of Rxx(1/B⊥) in b, e, and h. The grey dash lines highlight the phase boundaries identified by FFT peaks. White arrows mark the phase space of SC4. d, Analysis of the partially isospin-polarized (PIP) phase. Data are extracted from the right half of c. Black squares and red dots are extracted peak positions near f = 0 and f = 1/2, while blue, green, and purple lines are calculated by f1 + f2, 2 × f1 + f2, and 3 × f1 + f2. For |D| < 0.16 V/nm, blue line coincides with f = 1/2 (the grey dash line), indicating one single Fermi pocket instead of three in the less-populated isospin flavor. g, Illustration of expected Fermi surface in the PIP phase, when two of the four isospin flavors have low carrier densities. Due to the trigonal warping term, three small pockets are expected for each less-occupied flavor (upper panel). If we introduce some anisotropy in X-direction, only two or one pockets per flavor are also allowed (lower panel). Our data favors the last scenario, suggesting spontaneous nematicity.

Extended Data Fig. 7 More Fermiology analysis data.

a, The raw quantum oscillation data for Fig. 3e. b, c, Full quantum oscillation data and its FFT spectrum, measured in D1 near SC1. Figure 4f corresponds to the left half of Extended Data Fig. 7c. From low density to high density, three phases can be resolved by its FFT spectrum: HM, PIP, and FM with annular Fermi surfaces (FS), respectively.

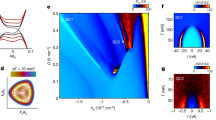

Extended Data Fig. 8 Phase diagram and Anomalous Hall Effect of the Three-quarter-metal phase.

a, b, Four-terminal resistance Rxx of D1 and D2 in the D > 0, electron-doped side. Yellow dash lines highlight the three-quarter-metal phase (TQM). c, Fourier transform of Rxx(1/B⊥) up to B⊥ = 1 T in D2, measured at the black dash line in b. The red dash line corresponds to fν = 1/3, and the white-shaded box highlights the TQM phase. The grey dash line highlights the phase boundary of the half-metal (HM) phase, and the white arrow outlines the range of n corresponding SC3, which is again next to the boundary of HM phase. d, e, Hysteresis loop of Hall resistance Rxy measured at the quarter-metal (QM) phase on the electron side (d) at the grey triangle in a, and on the hole side (e). Data are anti-symmetrized with positive and negative magnetic field (also for f). The anomalous Hall signal and the hysteresis effect are the signatures of valley polarization. f, Hall resistance Rxy measured at full-metal (FM) phase and TQM phase, at the blue and red dot marker position in a. Anomalous Hall effect is observed in the TQM phase but not in the FM phase, indicating a net valley polarization in the TQM phase.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Full phase diagram near SC1 in D1 and D3 when carriers are close to TMD.

Longitudinal resistance Rxx as a function of n & D, measured at B = 0 T in (a) D1, D < 0 and (b) D3, D > 0. In D1, even towards the boundary of the HM phase, no signatures of superconductivity can be found. SC4 in D3 is highlighted by the yellow dashed box.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Shi, X., Ye, S. et al. Impact of spin–orbit coupling on superconductivity in rhombohedral graphene. Nat. Mater. 24, 1058–1065 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02156-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02156-3

This article is cited by

-

Signatures of chiral superconductivity in rhombohedral graphene

Nature (2025)

-

Isospin magnetic texture and intervalley exchange interaction in rhombohedral tetralayer graphene

Nature Physics (2025)

-

Moiré-driven band renormalization and quantum transport in twisted 2D materials

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2025)