Abstract

Difficulties in antibiotic treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) are partly thought to be due to heterogeneity in growth. Although the ability of bacterial pathogens to regulate growth is crucial to control homeostasis, virulence and drug responses, single-cell growth and cell cycle behaviours of Mtb are poorly characterized. Here we use time-lapse, single-cell imaging of Mtb coupled with mathematical modelling to observe asymmetric growth and heterogeneity in cell size, interdivision time and elongation speed. We find that, contrary to Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mtb initiates cell growth not only from the old pole but also from new poles or both poles. Whereas most organisms grow exponentially at the single-cell level, Mtb has a linear growth mode. Our data show that the growth behaviour of Mtb diverges from that of model bacteria, provide details into how Mtb grows and creates heterogeneity and suggest that growth regulation may also diverge from that in other bacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Tuberculosis remains challenging to treat, requiring lengthy multidrug treatment due to heterogeneity in host response and the behaviours of individual Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) bacilli1,2,3,4,5,6. Drug-tolerant subpopulations of Mtb show different characteristics in growth, metabolic state and gene regulation7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Therefore, the ability of Mtb to develop heterogeneity in many cellular processes, including growth behaviours, is thought to be a major obstacle in developing shortened therapies3,14,15,16. Phenotypic switching to a slow growth state to create persistence has been observed in other bacteria, including Escherichia coli17 and Salmonella18,19. Despite the critical role of growth variation in the ability of bacteria to tolerate drug treatment, the basic growth behaviours and heterogeneity in growth characteristics of Mtb are unknown, making it challenging to study how growth variation is created and maintained in this pathogen.

Single-cell-level growth studies of mycobacteria have focused on the non-pathogenic species Mycobacterium smegmatis, which is faster growing and larger than Mtb20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Mycobacteria elongate from their poles, and M. smegmatis grow and divide asymmetrically, creating variation in growth behaviours between sister cells (Supplementary Fig. 1, first row). M. smegmatis elongate more from their old poles, and the sister inheriting the old pole (accelerator cell) is longer at birth and grows faster than its sister (alternator cell). Our understanding of growth behaviours in M. smegmatis is based on data from live-cell and fixed-cell imaging, and practical challenges have made it difficult to perform analogous live-cell imaging experiments in Mtb owing to its slow-growing nature, small size and the requirement for handling Mtb in biosafety level 3 conditions. As a result, the collective understanding of growth behaviours in Mtb is predominantly based on detailed studies of M. smegmatis and limited verification by fixed-cell imaging in Mtb20,22,24,26,27,28,29. Although there is evidence that Mtb can grow and divide asymmetrically30,31, it may be that the growth behaviours of Mtb are not very similar to those of M. smegmatis, given the difference in timescales and dimensions. For example, the doubling time of M. smegmatis ranges from 3 h to 5 h (refs. 25,32,33,34) whereas Mtb doubles every ~18 h in rich medium, which increases in host-mimicking conditions3,35,36,37. The fundamental differences in size, growth rate and ribosome density of M. smegmatis and Mtb suggest that understanding the growth behaviours of Mtb requires a direct study of Mtb using time-lapse imaging rather than a transfer of learning from M. smegmatis31,38.

Although cells double in number in each generation with their population growing exponentially, it is unclear a priori how a single cell grows. Analysis of single-cell data in most bacteria, including M. smegmatis and even archaea, suggests exponential growth, attributed to ribosome self-production and protein synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 1, second row)39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. E. coli shows super-exponential growth during later cell cycle stages47,48,49, while Bacillus subtilis follows a biphasic growth pattern with linear growth until a critical size is reached, followed by exponential growth for a fixed time50. Corynebacterium glutamicum, a tip grower like mycobacteria, shows asymptotic linear growth, in which the rate-limiting step for growth is the synthesis of the polar cell wall51. Complex growth rate trends are observed in eukaryotic organisms such as the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe52,53, underscoring the importance of understanding growth modes for homeostasis and cell cycle regulation. Determining how cells grow is crucial as the growth mode constrains which molecular mechanisms may be involved in cell growth52,54,55. Despite the critical role of growth for tuberculosis pathogenesis and drug response, we have lacked an understanding of the growth mode of Mtb.

In this Article, we characterize the fundamental single-cell growth characteristics and growth mode of Mtb. Using time-lapse imaging, we measured single-cell growth and cell cycle parameters to describe the Mtb growth mode and detailed growth behaviours, including cell size parameters and the origins of growth heterogeneity. We show that Mtb grows and divides asymmetrically and exhibits high levels of heterogeneity in cell size, interdivision time and elongation speed. However, unlike M. smegmatis, Mtb has accelerator and alternator subpopulations that do not show different growth behaviours, suggesting that Mtb creates heterogeneity via novel mechanisms. We also observed that Mtb breaks the previously held polar growth model in which elongation occurs first from the old pole. Instead, we find that Mtb cells can grow in three distinct patterns: from the old pole first (consistent with previous models), from the new pole first or from both poles together (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, we found that the dominant growth mode of Mtb is linear at the single-cell level throughout the cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. 1). Overall, our study establishes that Mtb growth behaviours cannot be learned from model organisms alone or by fixed-cell imaging, and provides a quantitative framework to study growth behaviours and variation in Mtb.

Results

Single-cell analysis of Mtb growth and cell cycle timing

We conducted live-cell imaging experiments to generate growth and cell cycle timing data for Mtb at the single-cell level (video set A, Supplementary Video 1). Annotation of these images allowed us to calculate many growth features at the single-cell level in 363 cells that were fully annotatable (from ~2,700 cells imaged in biological triplicate videos), including cell length at birth (Lb) and division (Ld), growth rate and elongation speed (Fig. 1a). We observed that cell size (medians of 2.3 µm at birth and 4.5 µm at division) and growth rates (median interdivision time of 16 h) measured by live-cell imaging were consistent with those reported using bulk measurement (Supplementary Notes Section 1). By tracking cell lineage, we identified sister cells (starting from the second generation) and annotated which sister inherited the old and new poles (accelerator and alternator cells, respectively, starting from the third generation) (Fig. 1a). To determine cell cycle timing, this base video set was made with Mtb strain CDC1551 carrying a fluorescent reporter of active DNA replication via a GFP tag on an episomal copy of single-stranded binding protein (SSB) (Fig. 1b–e and Extended Data Fig. 1a–f)56. By annotating when SSB–GFP foci appear and disappear, we calculated the length of the B, C and D periods for single cells, the average duration of each period in the total population (Fig. 1f,g) and the SSB foci location (Extended Data Fig. 1g). In Mtb, the B, C and D periods comprise 21%, 58% and 20%, respectively, of the total cell cycle duration (Fig. 1f) compared with 4%, 69% and 20%, respectively, for M. smegmatis, suggesting that the cell cycle periods were not proportionally similar in Mtb and M. smegmatis (Fig. 1f,g)25,56,57.

a, Schematic of growth parameters derived from Mtb across generations by time-lapse imaging. Cells loaded into the device (first generation) establish the pole age for the next generations but are excluded from analysis owing to incomplete cell cycle observation. In the second and subsequent generations, all growth features are determined, including Lb, DNA replication initiation (Li), Ld, interdivision time (Td), growth rate (λ), elongation speed \(\left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\right)\) and identification of old and new poles. In the third (and subsequent) generations, we identify accelerators (acc) (n = 173) and alternators (alt) (n = 130). In baseline experiments (video set A), cell cycle timing at the single-cell level is determined using an SSB–GFP reporter strain of Mtb (total cell n = 363). b, Determination of cell cycle state using SSB–GFP. SSB binds to replication forks81,82, with green foci indicating ongoing chromosome replication (C period); there were no visible foci before and after replication (B and D periods, respectively). The yellow arrows highlight the foci. Scale bars = 2 µm. c, Single-cell traces of SSB–GFP localization with hourly timepoints corresponding to b. The distance from the x-axis to the black circle represents cell length. The green circles indicate SSB–GFP foci localization along the cell body. The asterisks correspond to the images shown in b. d, Annotation of the cell cycle state in a cell with an E period, in which a small population (11%) initiates replication before division (foci positive)25. Daughter cells inheriting the foci enter directly into the C period. The yellow arrows highlight the foci, and the white dashed lines outline some individual Mtb cells. Scale bars = 2 µm. e, Single-cell SSB–GFP traces with hourly timepoints corresponding to d. The green circles indicate SSB–GFP foci. The asterisks correspond to the images shown in d. Length in c and e is unitless. f,g, Cell cycle timing in Mtb (f) and M. smegmatis (g). The average time and proportion of each cell cycle period are shown (B: pre-replication, C: DNA replication, D: post-replication, E: new DNA replication after a D period but before division). The M. smegmatis data are from a previous study25.

Heterogeneity in Mtb growth characteristics

Studies of mycobacterial growth characteristics have been performed primarily in M. smegmatis25,26,34,58,59. In M. smegmatis, growth and division are asymmetric, giving rise to more heterogeneity in growth characteristics than in other bacterial species4,25,26,27,28,60. To describe Mtb growth characteristics and compare levels of heterogeneity with those of M. smegmatis, we compared the distributions of lengths at birth and division, elongation speed and interdivision time of Mtb with those of M. smegmatis (Fig. 2a,b). We observed that Mtb growth is heterogeneous to the same degree as M. smegmatis growth for birth length (Mtb 19% and M. smegmatis 19% in coefficient of variation (CV), P = 1) and elongation speed (Mtb 22% and M. smegmatis 23% in CV, P = 0.41). Heterogeneity is increased in Mtb compared with that in M. smegmatis for division length (Mtb 17% and M. smegmatis 15% in CV, P = 0.018) and interdivision time (Mtb 28% and M. smegmatis 21% in CV, P = 1.42 × 10−7). We also observed notable differences in growth and cell cycle behaviours between Mtb and Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), with a higher variation in interdivision time observed in Mtb than in BCG (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

a,b, Distributions of Lb, Ld, Td and elongation speed \(\left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\right)\) are shown for both Mtb (n = 363; video set A) (a) and M. smegmatis (n = 391) (b). The coefficient of variation is shown in the upper right corner of each plot. The centre line of each box-and-whisker plot indicates the median. The left whisker extends from the minimum value to the lower quartile, and the right whisker extends from the upper quartile to the maximum value. The M. smegmatis data are from a previous study25. c,d, Growth property distributions are compared between acc and alt cells in Mtb (n of acc = 173, n of alt = 130) (c) and M. smegmatis (n of acc = 193, n of alt = 188) (d). Lb, Ld, elongation speed, growth amount and Td are compared between acc and alt, respectively. Horizontal lines mark the median value for each sample. The M. smegmatis data are from a previous study25. P values were calculated using the two-sided, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. In Mtb, the P values for each comparison are 0.024, 0.66, 0.39, 0.27 and 0.80, respectively (c). The P values for M. smegmatis are 8.29 × 10−23, 6.66 × 10−20, 2.20 × 10−9, 0.0004 and 0.070, respectively (d). Mann–Whitney U = 9,542, 10,908, 10,592, 10,419 and 11,050 in Mtb and 7,576, 8,326, 11,712, 14,335 and 16,207 in M. smegmatis, respectively. e,f, Distributions of division asymmetry in Mtb, M. smegmatis and E. coli. The distributions of division asymmetry in Mtb (e) and M. smegmatis (f) are calculated using the equation Lb of alt cell (daughter cell)/Ld of mother cell. The division symmetry of E. coli is calculated using the equation Lb of daughter cell/Ld of mother cell (e). The M. smegmatis and E. coli data are from previous studies25,83. The dashed lines at 0.5 indicate perfect symmetry. The CVs of Mtb, E. coli and M. smegmatis are 12%, 6% and 22%, respectively. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. NS, not significant.

Growth properties are independent of pole age

Growth and division asymmetry in M. smegmatis leads to a deterministic heterogeneity in growth properties. For example, the accelerator cells are longer, elongate more and elongate faster than the alternator cells (Fig. 2d)25,26,27,28. Because Mtb shows slightly more heterogeneous growth behaviours in cell sizes and interdivision time than M. smegmatis, we speculated that differences in growth characteristics between accelerator and alternator cells would be amplified in Mtb. Instead, we found no significant difference in their behaviours except for a slight difference in cell size where accelerator cells are born longer than alternator cells that did not remain different when we considered the batch effects of experimental replicates (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 3)61. Therefore, we conclude that accelerator and alternator cells do not show different growth behaviours in Mtb as they do in M. smegmatis.

Mtb division asymmetry is variable

Because accelerator and alternator cells show similar growth behaviours in Mtb, including cell size, we speculated that division might be relatively symmetric compared with that of M. smegmatis. We quantified the division asymmetry level by calculating the ratio of the length of the alternator cell at birth to the sum of the length of both sisters at birth. Accordingly, the distribution of division asymmetry would centre around 0.5 for symmetric division and below 0.5 when the alternator cells are smaller than the accelerator cells (Fig. 2e,f). Reflecting the relatively minor difference in birth sizes between accelerator and alternator cells in Mtb compared with M. smegmatis, we observed that the Mtb distribution is centred near 0.5 (0.49), whereas the M. smegmatis distribution is centred around 0.45 (Fig. 2e,f). We noted that the distribution of division asymmetry for Mtb, although narrower than in M. smegmatis (CV of 12% versus 22%, P = 1 × 10−17; Fig. 2f), is significantly more variable than in E. coli (CV of 6%, P = 5 × 10−29; Fig. 2e). Together, these data suggest that growth heterogeneity is less systematically asymmetric in Mtb than it is in M. smegmatis, but the variation in the level of division asymmetry is still greater than that of other model organisms such as E. coli.

Mtb growth is mildly asymmetric

Mycobacterial elongation is polar, and growth is faster (and earlier) from the old pole than from the new pole in M. smegmatis26,27,30,62,63,64. In Mtb, fixed-cell imaging of growth patterns has suggested that Mtb growth is also asymmetric but less asymmetric than in M. smegmatis27,28,30,64,65. However, it has been challenging to quantify the asymmetric growth pattern and determine whether there is more growth from the old pole than from the new pole without time-lapse imaging. By tracking cell surface features, new end take-off (NETO) was observed, that is, the old pole elongates before the new pole elongates, in both Mtb and M. smegmatis64. To measure growth asymmetry throughout entire division cycles in Mtb, we followed Mtb growth by time-lapse imaging for ~6 days (140 h) after pulse labelling Mtb with blue fluorescent d-alanine (HADA) for 24 h (video set B) (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Video 2). We used mathematical models to quantify growth by analysing growth annotations over time. On the basis of previous results of NETO64, we selected between linear and bilinear models, using Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) metrics to characterize the length growth at each pole as a function of time from birth (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 4)66. A linear model implies constant elongation speed throughout the cell cycle, whereas a bilinear model implies a lag period followed by constant-speed growth.

a, A 5-h-interval image sequence of FDAA-labelled Mtb cells. Individual cells were fully labelled with HADA at the beginning of the time-lapse imaging. The unlabelled area at the poles indicates a newly grown cell wall since the start of the imaging. The white dashed lines outline some individual Mtb cells. Scale bars = 2 µm. b, Schematic diagram of polar growth quantification using FDAA-labelled Mtb. The green area within the cell indicates FDAA (HADA) labelling. The white (unlabelled) area at the poles indicates the new cell wall. The white dashed line indicates septum formation. c, Distribution of growth asymmetry in Mtb. The histogram is fit with a Gaussian. The grey dashed line (score of 0.5) represents symmetric growth (mean value = 0.58, n = 147).

For each cell, we calculated a growth asymmetry metric, which is the proportion of total growth over one cell cycle that is contributed by the old pole, that is, \(\text{Growth asymmetry} = \frac{{\rm{Growth}}\;{\rm{from}}\;{\rm{old}}\;{\rm{pole}}}{{\rm{Total}}\;{\rm{growth}}\;{\rm{from}}\;{\rm{both}}\;{\rm{poles}}}\). A growth asymmetry score of 0.5 indicates symmetric growth (equal growth from the old and the new old), and scores <0.5 and >0.5 indicate more growth contribution by the new and the old poles, respectively. Using the polar growth data from linear and bilinear fits, we found the distribution of growth asymmetry to be centred around 0.54 (Fig. 3c), indicating that the old pole elongates more than the new pole in a larger subpopulation of Mtb.

Mtb growth is linear at the single-cell level

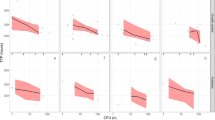

The similarity in the heterogeneity of growth characteristics, such as cell size at birth and division between Mtb and M. smegmatis, made us question whether they grow in a similar manner, qualitatively, at the single-cell level. In previous studies, M. smegmatis has been observed to grow exponentially21,25,34. Another study reported bilinear growth of M. smegmatis cells64 in which cells grow linearly for some time after which they change to a different elongation speed. To study the mode of growth of Mtb, we used a differential method for the analysis of growth during the cell cycle, such as plots of changes in cell length \(\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\) versus time since birth (t), rather than cell length (L) versus t (Supplementary Notes Section 2)67. Recent works support the effectiveness of methods such as elongation speed \(\left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\right)\) versus age \(\left(\frac{t}{\rm{Td}}\right)\) and growth rate \(\left(\frac{1}{L}\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\right)\) versus age plots for understanding the mode of growth47,49,50. Findings include the super-exponential growth of E. coli47, biphasic growth of B. subtilis and asymptotic linear growth of C. glutamicum50,51. In this study, we apply similar approaches to elucidate the mode of Mtb growth (Supplementary Notes Section 3).

For exponentially growing cells, the growth rate \(\left(\frac{1}{L}\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\right)\) is constant throughout the cell cycle while the elongation speed \(\left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\right)\) increases with age (Supplementary Fig. 1). The ideal linear fit of the growth rate versus age plot would be a horizontal line with the y-intercept equal to the average growth rate. By contrast, for linear growth, the binned data trend for elongation speed will be constant throughout the cell cycle, and hence, the growth rate decreases with age (Supplementary Fig. 1)47.

On plotting growth rate versus age using the data of Mtb grown in unbuffered medium (video set A, as described in Fig. 1), we show that the growth rate decreases with age (Fig. 4a) while the elongation speed versus age plot stays constant (Fig. 4b). We found that the binned data trend (blue) from the experiments was largely consistent (barring small fluctuations) with the trend obtained using simulations of linear growth with measurement noise taken into account (Fig. 4 and Methods). The mode of growth was also found to be linear when the experimental replicates were analysed separately (Extended Data Fig. 5).

a, The binned data trend of the growth rate \(\left(\frac{1}{L}\frac{{{\rm{d}}L}}{{{\rm{d}}t}}\right)\) versus age plot is shown for Mtb data (video set A, n = 363 for unbuffered; video set C, n = 135 for acidic; video set B, n = 248 for neutral condition, using the cells that are born and divided during the video only). The binned data trends decrease with age and are largely consistent with the predicted trends obtained using simulations of linear growth (red lines). b, The binned data trend of the elongation speed versus age plot is shown for Mtb data. The binned data trends are nearly constant, consistent with linear growth simulations (red lines). The dots and error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. Age in a and b is unitless.

To investigate whether the linear growth behaviour of Mtb extends beyond standard growth conditions (unbuffered), we examined Mtb growth in acidic (pH 5.9, resembling the pH during macrophage infection) and neutral media68,69. We observed consistent linear growth in both acidic (video set C, Supplementary Video 3) and neutral (video set B, Supplementary Video 2) growth conditions, as evidenced by the trends of growth rate and elongation speed (Fig. 4).

Polar growth can start from either or both poles

A previous study on polar growth in mycobacteria indicated that Mtb elongates via NETO dynamics in which the old pole starts growing linearly from birth while the new pole undergoes linear growth after a certain lag time64. This NETO dynamics predicts a growth change when the new pole starts growing. In this section, we investigate how to reconcile polar growth with the roughly linear growth we observed in Fig. 4.

As introduced previously, pulse label experiments were used to observe growth at the old and new poles (Fig. 3a,b). Based on NETO, the old pole is expected to grow from birth and the new pole to be delayed before growing (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 4a,d)64. However, as shown in Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 4b,e, approximately half of the cells started growing from both poles within 1 h of cell birth—45.6% in neutral pH and 49.5% in acidic pH, from n = 147 and 101 cells in video sets B and C, respectively (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 1). Following the ‘NETO’ nomenclature, we call these dynamics ‘both ends immediately take-off’ (BEITO). The joint distribution for the time (relative to birth) at which the old pole and the new pole start growing peaks at short times on both axes in both neutral and acidic pH (Fig. 5d). Aside from NETO dynamics64, we have also found cases in which the new pole starts growing before the old pole as shown in Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 4c,f (‘old end take-off’ (OETO)). In neutral pH, we found that NETO was observed in 33.3% of the total cells, while OETO was observed in 21.1% of the total cells. In acidic pH, the proportions for NETO and OETO were 37.6% and 12.9%, respectively (Fig. 5d). The elongation speeds are greater for the old pole growth than for the new pole growth in both neutral and acidic pH conditions (Fig. 5e). The overall greater elongation from the old pole relative to the new pole may be due to a combined effect of slightly more cases of NETO than OETO and a faster elongation speed from the old pole.

a–c, Representative examples of different polar growth dynamics (video set B; other examples are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4). The elongation length at each pole is shown as a function of time. The lines represent the best fit to the data and can be either linear or bilinear. a, The new pole starts elongating later than the old pole (NETO). b, Both poles elongate from the beginning of the cell cycle (BEITO). c, The new pole starts elongating before the old pole (OETO). The legend in a also applies to b and c. d, Joint distribution of the timings when the old and new poles start growing in neutral (n = 147) and acidic pH (n = 101) (video set B and C, respectively). e, Distribution of the elongation speed at each pole in neutral and acidic pH (video set B and C, respectively). f, Growth rate and elongation speed versus age in neutral (n = 147) and acidic (n = 101) growth conditions. Simulations of the proposed model are carried out using parameters derived from experimental data. Growth rate trends as a function of age and elongation speed versus age are compared between simulations (black) and experiments (red) for neutral pH and acidic pH conditions. The dots and error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. Note that here we are showing numerical simulations with a comparable number of cells to that used in the experiment, leading to significant fluctuations. These fluctuations can obscure the deviations from linearity predicted by the full model, which accounts for different subpopulations. The model predictions, averaged over a larger population of cells, are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. Age in f is unitless.

Using simulations (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Notes Section 4), we reconcile the population-averaged linear growth across the cell cycle (Fig. 4) with the pattern of polar growth with different ends growing at different times (Fig. 5). This comes about primarily owing to the early take-off times in NETO and OETO populations.

To conclude, the cells undergo polar growth, with both poles starting to grow from the beginning of the cell cycle in half of the cells (BEITO), and in the other half, either pole can start growing first. Using simulations based on our experimental data and distribution of cells that are BEITO, NETO and OETO, we could reproduce the largely constant elongation speed versus age curve observed in the experiments.

Discussion

A key feature of the pathogenesis of Mtb is slow growth and phenotypic heterogeneity, which is thought to enable Mtb to reside, survive and hide in multiple sites of infection in humans4,36,70. Therefore, we have an urgent need to understand how Mtb grows and regulates growth heterogeneity to understand their bet-hedging strategies that enable population-level drug and immune evasion. Using time-lapse imaging, we describe the growth behaviours and heterogeneity of tubercle bacilli in detail. Previous studies hinted at less asymmetric polar growth in Mtb than in M. smegmatis, which would attenuate differences in growth behaviours between sister cells and overall variation in growth behaviours30,64. However, we show that cell-to-cell variation in cell size, interdivision time and growth speed was similar and high compared with those of model rod-shaped bacteria. Because M. smegmatis generates two types of sister cells (accelerator and alternator) via their growth pattern, which gives rise to subpopulations with different growth characteristics and drug susceptibility patterns27,28, the tuberculosis field has sought to understand how accelerator and alternator cells contribute to drug tolerance in Mtb. However, our results here suggest that they do not show deterministically different growth behaviours in Mtb, suggesting the need to explore alternative sources of growth heterogeneity in Mtb, potentially polar growth patterns, gene or protein distributions, or metabolic state, to better understand virulence and drug responses. Whereas numerous studies have established that M. smegmatis initiates growth from the old pole25,27,28,64, we found that there are diverse polar growth types in Mtb: some cells grow from the new pole or old pole first and others elongate from both poles at once soon after birth. The three polar growth patterns observed in this study—NETO, OETO and BEITO—may play a role in driving phenotypic heterogeneity, including differences in drug and immune tolerance.

Combining single-cell growth data with mathematical modelling, we show that the Mtb growth mode at the single-cell level is linear throughout the cell cycle. Most bacterial species are thought to grow exponentially in biomass and volume41,42,44,46,47. In this study, we showed that Mtb growth was nearly linear not only in an unbuffered rich growth condition but also in slower, more stringent growth conditions in an acidic medium, mimicking a stressor that the bacteria face during infection. The persistence of linear growth behaviour in both rich and acidic conditions suggests that linear growth is the dominant growth mode of Mtb and not the exception.

Understanding bacterial growth at the single-cell level is crucial in bacterial physiology. While a prevalent framework implicates ribosome-centric growth models (Supplementary Discussion), our discovery of linear growth in Mtb challenges this paradigm, suggesting the need for novel regulatory mechanisms of growth mode. Various mechanisms, including gene dosage and cell wall growth limitations, may underlie this linear growth, highlighting the complexity of bacterial growth dynamics and the necessity for further investigation into the growth mechanisms of Mtb.

In addition to exploring the question of how linear growth is observed in Mtb, one may also enquire about the underlying reasons for this phenomenon. In bacteria such as E. coli, the existing paradigm is that the selection pressure faced by cells during evolution has led them to grow as fast as possible (barring the presence of non-growing subpopulations such as persisters)17,71. Indeed, in long-term evolution experiments, growth rate has significantly increased over the generations72, and extensions of the ribosome-limited model for growth showed that making ribosomes consist of numerous, smaller proteins leads to a significant growth rate increase73, thus interpreting the ribosome structure itself in terms of growth rate optimization. This picture appears invalid in Mtb, suggesting that it faces different constraints and selection pressure. This could arise owing to its constant battle with the immune system, making its main challenge evading it rather than optimizing growth rate.

Our study provides a baseline understanding of Mtb growth properties and their variations in a population of cells. These data include cell sizes, cell cycle timing and elongation speeds. We find that the growth mode and level of heterogeneity are together unique and cannot be explained using models developed in model bacteria or other closely related species such as M. smegmatis. Given the critical role of growth, metabolic state and adaptation to fluctuating environments that Mtb faces during infection to Mtb virulence and drug response, further studies on the growth behaviours of Mtb and other pathogens will enable us to develop improved therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Overview of the video sets

For the baseline video set (video set A), we used Mtb CDC1551 strain harbouring the SSB–GFP reporter, which was grown in unbuffered (pH ~6.8) standard (supplemented Middlebrook 7H9) growth medium at 37 °C. Time-lapse imaging was conducted for 96 h, with images taken every hour.

Two additional video sets were made using the fluorescent d-amino acid (FDAA) pulse-labelled CDC1551 wild-type strain. Videos were made in neutral (pH 7.0, video set B) or acidic (pH 5.9, video set C) standard (supplemented 7H9) growth medium at 37 °C. Time-lapse imaging was conducted for 140 h, with images captured every hour. All the videos were made inside a biosafety level 3 facility.

Bacterial strain

Mtb CDC1551 strain (video sets B and C) and its transformant with a hygromycin-resistant replicating plasmid expressing SSB fused to a green fluorescent protein (SSB–GFP) and smyc′::mCherry (video set A) were used in this study56. All live-cell work with these strains was performed inside a biosafety level 3 facility.

Bacterial culture

Mtb was grown in a standard medium consisting of 7H9 broth (ThermoFisher; DF0713-17-9) with 0.05% Tween 80 (ThermoFisher; BP338-500), 0.2% glycerol (ThermoFisher; G33-1) and 10% Middlebrook OADC (ThermoFisher; B12351). For the SSB–GFP reporter strain (video set A), 50 µg ml−1 of hygromycin (ThermoFisher; 10687010) was added to maintain SSB–GFP, smyc′::mCherry. The Mtb strain was grown to an OD600 of 0.5–1.0 from frozen aliquots at 37 °C with mild agitation. Cultures were subcultured via back dilution to an OD600 0.05 and grown to the mid-log phase (OD600 0.5–0.7) before experimental use. For videos in which polar growth is assessed (video sets B and C), Mtb cells were backdiluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in 10 ml 7H9 medium (unbuffered) supplemented with 100 µM HADA (see below) for 24 h. Labelled cells were washed twice with PBS (ThermoFisher; 20012-027) + 0.2% Tween 80 (PBST) and resuspended in pH 5.9 or 7.0-adjusted fresh 7H9 medium that was supplemented with sterile spent medium (50:50) for loading into the microfluidic devices for time-lapse imaging.

FDAA labelling

The blue FDAA, HADA (Tocris; 6647), was used for video set B and C. HADA powder was dissolved in DMSO to a stock concentration of 100 mM and stored for a short period at −80 °C. Cells were incubated in 100 µM HADA for 24 h before the start of the imaging.

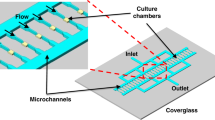

Microfluidic device

The highest-throughput microfluidics for studying cell growth in rod-shaped bacteria require that the bacteria are loaded into thin channels40,74,75. However, mycobacteria cannot be loaded into these channels because they are coated in a thick mycolic acid layer in their cell wall, making them too sticky for these devices (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

We overcame this challenge by optimizing protocols and using a custom microfluidic device to achieve long-term time-lapse imaging of Mtb in a biosafety level 3 laboratory. We used devices previously designed to study M. smegmatis to ensure freedom of movement in polar growth and v-snapping23,25. We observed that, whereas M. smegmatis grows with a new medium constantly flowing in the microfluidic devices, Mtb enters growth arrest. Culture filtrate is required to enable Mtb single cells to grow under constant flow; therefore, we supplemented the new medium flowing into the device with culture filtrate at a ratio of 1:1 to avoid growth arrest. With these protocols, we were able to achieve a consistent growth pattern in Mtb over 4 days of imaging with a doubling time (~17 h) that is consistent with the doubling times of Mtb in bulk culture76,77,78.

Live-cell microscopy

Before loading Mtb cells into a custom polydimethylsiloxane microfluidic device, cells were filtered through a 10 μm membrane filter to remove clumps. Mtb cells were loaded into a microfluidic device through the outlet port using a syringe that contains filtered Mtb cell culture23. The devices contain a main microfluidic feeding channel with a height of 10–17 μm and viewing chambers with a diameter of 60 μm and a height of 0.8–0.9 μm. Fresh medium was delivered to cells at a flow rate of 5 μl min−1 using a microfluidic syringe pump. The device was placed on an automated microscope stage within an environmental chamber maintained at 37 °C. Mtb cells were imaged at ×60 magnification using a widefield Deltavision PersonalDV (Applied Precision), which is located inside a biosafety level 3 facility. For video set A, cells were illuminated with an InsightSSI Solid State Illumination System every hour for 96 h. Cells were imaged using transmitted light bright-field microscopy, GFP (475 nm/525 nm) and mCherry (575 nm/625 nm). mCherry was imaged to ensure the presence of the plasmid and was not used for analysis. The videos were performed in biological triplicate, with each replicate performed separately in different microfluidic devices on different days. For FDAA pulse-labelled videos (video sets B and C), cells were imaged every hour for 140 h using transmitted light bright-field microscopy, and HADA was visualized with a cyan fluorescent protein filter (433 nm/475 nm).

Live-cell image segmentation

For video set A, ImageJ plugin ObjectJ (version 1.03x) was used to hand-annotate cell length, growth and cell cycle progression throughout the image stack (time lapse). Single cells were annotated23,25 for cell length by marking two points at each pole. Additional points (up to four points in total within a cell) are annotated when foci were present. The SSB–GFP reporter forms a green fluorescent focus during DNA replication. Newly divided cells generally did not have an SSB–GFP focus, labelled as the pre-replication period (B period). The period when one or two SSB–GFP foci were detected was defined as the replication period (C period), and the subsequent period when foci were absent was labelled as the post-replication period (D period). Some cells had one or two foci after the division period but before septation; in these cases, we labelled those occurrences as the pre-division period (E period)25,56,57. Cell poles and visible foci were annotated in each frame—two points at each pole of a single cell were annotated if no foci were detected, while three (one focus) or four (two foci) points were annotated when foci appeared. The localizations of foci were manually analysed (custom code) and used to determine cell cycle timing. The annotation in each frame was extracted, containing information on cell length and cell cycle progression over time (1 h timescale). The ObjectJ data were exported to an XML file. Information on mother–daughter and accelerator–alternator cell relationships was also collected from cell pedigree trees using custom scripts in MATLAB for analysis; specifically, these scripts calculate and collate single-cell data—length at birth and division, duration of each cell cycle period, SSB foci presence and localization, accelerator–alternator status and pedigree relationships between cells (for example, mother–daughter–sister cell relations). During time-lapse imaging, we observed a rare subpopulation in which the cells express a high intensity of GFP. We observed that these cells did not divide and entered growth arrest. This may be due to phototoxicity caused by high SSB–GFP abundance. These cells were excluded from annotation.

For FDAA pulse-labelled videos (video sets B and C), using the HADA label as a marker of old cell wall material, we annotated growth from the new and the old poles in cells born during the video (so that we could establish pole age) from birth to division (n = 248) (Fig. 3a,b). The cell poles and HADA labelling were hand annotated in each frame using ImageJ (version 1.53f) with an ObjectJ plugin. Whole-cell labelling was annotated at each pole in the first time point. When cells elongated, a non-labelled area appeared, representing the new growth site. In cases in which cells elongated from only one pole, three points were annotated. When cells elongated from both poles, four points were annotated, starting from one pole (single point), then the HADA-labelled cell body (two points) and then the other pole (single point). After annotation, the x and y coordinates of each annotation point were extracted, and the distance was calculated using the Euclidean distance formula.

Simulations

In Fig. 4, we show that Mtb growth was largely consistent with linear growth simulations. Here we describe the model used for the linear growth simulations and the simulation methodology. Simulations of linear growth were carried out for 500 cells. Elongation speeds were assumed to have a Gaussian distribution with the mean \({\langle \lambda }_{\rm{lin}}\rangle\) and standard deviation \({\rm{CV}}_{\lambda ,{\rm{lin}}}\langle {\lambda }_{\rm{lin}}\rangle\) determined using the experiments. They were calculated as the mean and standard deviation of \(\frac{\rm{{Ld}-{Lb}}}{\rm{Td}}\) where Lb, Ld and Td are length at birth, length at division and the generation time, respectively. Values for (\(\langle {\lambda }_{\rm{lin}}\rangle\) in μm h−1, \({\rm{C{V}}}_{\lambda ,{\rm{lin}}}\)) are as follows: unbuffered medium (0.1442, 0.226), acidic medium (0.0741, 0.286), neutral medium (0.069, 0.240), replicate 1 (0.1663, 0.181), replicate 2 (0.134, 0.193) and replicate 3 (0.1309, 0.220). The elongation speed was determined at the start of the cell cycle. The length at birth for each cell was sampled from a normal distribution with mean \(\langle \rm{{L}{b}}\rangle\) and CV (CVb) fixed using the experimental data. The values (\(\langle \rm{{L}{b}}\rangle\) in μm, CVb) are as follows: unbuffered medium (2.37, 0.19), acidic medium (2.34, 0.24), neutral medium (2.25, 0.18), replicate 1 (2.60, 0.19), replicate 2 (2.22, 0.18) and replicate 3 (2.27, 0.17). The cells divided upon reaching size \({\rm{Ld}}=2(1-\alpha ){\rm{Lb}}+2\alpha \varDelta +\eta\). Here Δ is a constant and α is the size regulation strategy that can take any value from 0 to 1. When α is 1, cells divide on reaching a particular size 2Δ (sizer), and for \(\alpha =\frac{1}{2}\), cells divide on adding a constant size Δ from birth. α and Δ are determined using the slope and intercept of the experimental Ld versus Lb plot, which are 2(1 − α) and 2αΔ, respectively79. η is the size additive division noise with mean zero and standard deviation (σbd). Our results are independent of the nature of division noise. The values for (α, Δ in μm, σbd in μm) are as follows: unbuffered medium (0.60, 2.28, 0.57), acidic medium (0.89, 2.77, 0.85), neutral medium (0.71, 2.26, 0.41), replicate 1 (0.61, 2.40, 0.66), replicate 2 (0.72, 2.26, 0.42) and replicate 3 (0.65, 2.18, 0.37). The length of each cell was measured at 1 h intervals. The measured length is the sum of the actual length of the growing cell and a measurement error normally distributed with mean zero and standard deviation determined from experiments (Supplementary Notes Section 5). The standard deviation values in μm are as follows: unbuffered medium (0.13), acidic medium (0.12), neutral medium (0.11), replicate 1 (0.14), replicate 2 (0.15) and replicate 3 (0.12).

We also investigated the effects of NETO, OETO and BEITO dynamics on the binned data trends of growth rate versus age and elongation speed versus age plots in Fig. 5f. We conducted simulations using the information of polar growth from the fluorescent HADA-labelled experiments in both neutral and acidic pH, which we will elaborate next. The simulations have the same number of cells as the experiments, that is, n = 101 for acidic and n = 147 for neutral pH conditions. Each cell is initialized to be born at a length sampled from a normal distribution with the mean (acidic, 2.30 μm; neutral, 2.29 μm) and CV (acidic, 0.24; neutral, 0.16) determined from the experiments. Each cell starts growing as BEITO with a probability equal to the fraction of BEITO cells in the experiments (~50% for acidic and ~46% for neutral pH). The elongation speed of old and new pole growth is drawn from independent normal distributions with the mean (acidic: old, 0.044 μm h−1; new, 0.036 μm h−1; neutral: old, 0.045 μm h−1; new, 0.034 μm h−1) and CV (acidic: old, 0.38; new, 0.42; neutral: old, 0.35; new, 0.40) determined from the experiments. For the remaining non-BEITO cells, growth does not occur from the poles until a certain take-off time. To accurately simulate the take-off time distributions, we sampled the timings with equal probability and with replacement from the non-BEITO cells obtained in the experiments. It ensured that the distribution of take-off times for the old and new poles and the proportion of NETO and OETO cells are similar in the simulations and experiments. The cell cycle ends once the cell reaches a particular division size (Ld) determined solely by the birth size (Lb), that is, mathematically, Ld = 2(1 − α)Lb + 2αΔbd + ζbd. The values of α and Δbd were obtained from the experiments (α = 0.83, Δbd = 2.89 μm for acidic pH and α = 0.8, Δbd = 2.34 μm for neutral pH), and ζbd is the normally distributed noise in the division size with mean 0 and standard deviation determined such that the standard deviation of the division size is the same in simulations and experiments (acidic: 0.85 μm; neutral: 0.40 μm). The length of the cell is measured from cell birth until cell division at 1 h time intervals. A measurement noise term is added to each measurement with mean 0 and standard deviation determined using HADA-labelled cells: in these experiments, the length of the HADA-labelled part of the cell is assumed to be constant (non-growing) throughout the cell cycle and the deviation from the constancy provides an estimate of the magnitude of measurement noise (acidic: 0.099 μm; neutral: 0.078 μm). In some of the cells, it is hard to visualize the growth of the new pole because of the finite resolution limit of imaging. In these cases, the new pole appears to be non-growing until some point in the cell cycle after which it experiences a sudden change in growth. We include these non-growth biases by sampling the times from experiments for which the new pole has no measured growth. We include this bias for completeness; however, we note that its exclusion does not change the results qualitatively.

Characterizing single trajectories using AIC and BIC values

We characterize the growth at the old and new poles using FDAA (HADA) labelling (Fig. 3). Figure 3a (middle panel) shows that the cells have an unlabelled part at the old pole after the first generation. The old pole growth is measured by adding unlabelled parts to the existing unlabelled region. The growth at the new pole is marked by the appearance of an unlabelled region at the new pole and, in a few cases, the growth of unlabelled parts to the existing unlabelled region. The aim is to identify the amount of growth at each pole and the time at which the pole growth starts. However, precise measurement of single-cell polar growth is difficult because the clumping of Mtb cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a) obscures the position of the poles and, thus, complicates the determination of the HADA-unlabelled part. This section explains the statistical models used to determine the polar growth at both ends at a single-cell level.

Previous studies have determined growth at each individual pole to be linear64. Linear growth is also supported by our results in the main text (Fig. 4). Thus, to determine the growth at each pole, we fit two different models to the length versus time trajectories: (1) linear growth and (2) bilinear growth, in which the length stays constant for a certain time and then increases linearly. Bilinear growth was used to characterize NETO64, in which it was proposed that the new pole starts growing after a time delay from cell birth. We assume that some old poles may also grow bilinearly (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 4c,f).

In cells that already have an unlabelled part at the old pole, we calculate the amount of old pole growth at time t from birth as the difference between the length of the unlabelled HADA region at the old pole at time t from birth and the initial unlabelled part at birth. The measured length grown can be negative for the old pole as the unlabelled HADA region at birth can be inaccurate due to cell clumping or cell tilting along the z-plane in the microfluidic chamber. We show examples of length grown versus time for the old pole (blue and green) and new pole (red) in Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 4. In most of the cells of the pulse label experiment, we do not observe a HADA-unlabelled region at the new pole at the time of birth. In these cells, the length grown at the new pole is the length of the unlabelled HADA region at the new pole. The length grown is marked as zero when we do not observe the unlabelled HADA region at a pole.

Next, we fit the two models discussed above for each single cell to the length grown at each pole versus time curves. The linear model is characterized by two parameters \(y= ax+b\), where \(a\) is the elongation speed of the pole and b is a measure of the unlabelled HADA region at cell birth. For the bilinear model, the underlying equation is

where \(a\), b and c are the elongation speed of the pole, the bias in determining the initial HADA-unlabelled region and the time when the pole starts growing (relative to birth), respectively. For fitting, we ignore those data points where the length grown is zero (the y-axis is zero). We minimize the squared sum of residuals (RSS); \({\rm{RSS}}={\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{\left(\;{y}_{i}-\widehat{{y}_{i}}\right)}^{2}\), where \({y}_{i}\) is the true value of the \({i}{\rm{th}}\) data point of the dependent variable and \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) is the predicted value from the model. To compare which of the two models better fits the single-cell trajectories, we use the AIC and the BIC. They are defined as

where k is the number of parameters in the model (k = 2 for linear, k = 3 for bilinear), N is the number of data points fitted and \(\widehat{L}\) is the maximum value of the model’s likelihood function. In the AIC and BIC methods, a model is favoured if it has a greater maximum likelihood value, and it is penalized for having a greater number of parameters, the penalty being different for AIC and BIC as shown in equations (2) and (3). Assuming that the errors (\({y}_{i}-\widehat{{y}_{i}}\)) are drawn from an independent and identical normal distribution, the AIC and BIC values can be simplified to66

The AIC and BIC values themselves have little significance. The relevant metric is the difference between AIC and BIC values of the two models being compared; in our case, they are ΔAIC = AIC(linear) − AIC(bilinear) and ΔBIC = BIC(linear) − BIC(bilinear). A model with a lower AIC and BIC value is preferred. In our case, the bilinear model is preferred if both ΔAIC and ΔBIC values are greater than zero, while the linear model is preferred if the ΔAIC and ΔBIC values are less than zero. In a few cases in which ΔAIC and ΔBIC values have opposite signs, the model with fewer parameters, that is, the linear model, is preferred.

Having chosen the appropriate model using the ΔAIC and ΔBIC values obtained upon fitting both models to the length versus time trajectories of each cell, we aim to calculate the time at which the growth at a particular pole starts, the elongation speed at that pole and the amount of growth at that pole. We discuss the calculation of these quantities for different cases of fit results obtained, first for old pole growth and subsequently for new pole growth.

A bilinear curve best fits the trajectory for old pole growth shown in Extended Data Fig. 4c. In these cases in which the old pole growth is bilinear, the value of parameter c (equation (1)) of the best bilinear fit denotes the time at which the pole starts elongating. The slope \(a\) is the elongation speed of the pole and the constant b is the bias in determining the initial unlabelled HADA region. Thus, the amount of polar growth during the cell cycle is the length increase within time c and Td (the doubling time). Mathematically, the amount of polar growth = \(a({\rm{Td}}-c)\). For the old pole growth trajectories in Extended Data Fig. 4a,b, where the best fits are linear, we assume that the growth starts from time 0. The y-intercept obtained (positive in (b) and negative in (c)) can be interpreted as the error in determining the initial unlabelled HADA region. The elongation speed is the slope of the best linear fit, and the amount of growth is equal to Slope × Td.

Next, we discuss the calculations of growth parameters for the new pole growth. We fit the non-zero length grown versus time data to the two models—linear and bilinear—and choose the appropriate model based on ΔAIC and ΔBIC values. In the trajectory shown in Extended Data Fig. 4c, the best fit is linear with a negative y-intercept. On extrapolating the best fit to y = 0, we obtain a positive time Ttrans. As we do not observe the unlabelled HADA region before this time point, we interpret the time Ttrans as the time when the pole starts growing. The raw data show the new pole to have a HADA label for some time after Ttrans because the unlabelled HADA region is small and might be undetectable in the videos until it reaches a particular length. Examining the videos shows that this length is around 0.2–0.4 µm. This can also be seen in Extended Data Fig. 4a–c trajectories, in which there is a sudden jump in the length of the new pole. The elongation speed is the slope of the best linear fit, and the amount of growth is Slope × (Td − Ttrans). In Extended Data Fig. 4b, the best linear fit has a positive y-intercept. In this case, we interpret the y-intercept as an initial undetectable HADA-unlabelled region at the new pole. The new pole starts growing from the beginning of the cell cycle with an elongation speed equalling the slope of the best linear fit. The amount of growth at the new pole during a cell cycle is Slope × Td. In Extended Data Fig. 4a, in which a bilinear fit better explains the length grown as a function of time, the interpretation of the fit is similar to that of the old pole. The constant parameter b in equation (1) denotes the HADA-unlabelled region at cell birth, c denotes the time when the new pole starts growing and the slope \(a\) denotes the elongation speed. The amount of growth is given by the same equation as that of the old pole, \(a({\rm{Td}}-c)\).

In a few cases, we observed that the new pole had an unlabelled HADA region at cell birth. In such cases, we analysed the new pole using the same method as the old pole, as discussed previously in this section.

We use the definition of BEITO as cells starting to grow from both poles within 1 h of birth. This is related to the error in estimating the value of c, the time when the pole starts growing. To calculate the accuracy in the estimation of parameter c, we generated 100 trajectories using the model (either linear or bilinear) determined for each pole and each cell. To the deterministic growth component—elongation speed and growing time—we added a noise that is normally distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation determined by the residuals. For each of the 100 trajectories, we again undertook the fitting and model selection procedure described above and obtained estimates of elongation speed and time delay before growth at that pole starts. The standard deviation of parameter c is obtained for the old pole and the new pole growth. The standard deviation for both poles in both acidic and neutral conditions is between 0.8 h and 1.1 h. Note that this is close to the time between successive measurements (Δt = 1 h) but much smaller than the mean interdivision time (35–45 h).

Statistics and reproducibility

The scatter plots are presented with median values. The two-sided, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test was performed throughout the features compared between accelerator and alternator cells within Mtb or M. smegmatis strains.

Significance between CV values was tested using an asymptotic test for the equality of coefficients of variation from k populations80. The test is commonly used to compare variation between k different groups with unequal sample sizes. In this work, we consider k = 2 because we conduct pairwise CV comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The test does quite well irrespective of the underlying distribution of the data (normal, log-normal, gamma) provided that the sample size is large (n = 20).

We used the package ‘cvequality’ (version 0.2.0) in R version 4.1.2 (202 1-11-01) to compare the coefficients of variation. Simulations and data analyses were performed using MATLAB version R202lb. Three-dimensional histograms were made using Python version 3.9.

Images from Fig. 1b,d and Supplementary Fig. 1a,b are representative of three biological replicates. Images from Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 1c are representative of two biological replicates. Single cells loaded into 40–60 separate microfluidic chambers were used for imaging, generating 40–60 videos per biological replicate. The videos from two biological replicates, part of which were used for Fig. 3a, include a total of 1,089 annotated single cells.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The primary datasets and the referenced datasets processed from time-lapse imaging annotations are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22930310 (ref. 84).

Code availability

The custom MATLAB code used in this study is available via GitHub at https://github.com/pkar96/Mtb-growth (ref. 85).

References

Mitchison, D. A. Role of individual drugs in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 4, 796–806 (2000).

Barry, C. E. et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 845–855 (2009).

Lenaerts, A., Barry, C. E. & Dartois, V. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis pathology, microenvironments and therapeutic responses. Immunol. Rev. 264, 288–307 (2015).

Cadena, A. M., Fortune, S. M. & Flynn, J. L. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 691–702 (2017).

Chung, E. S., Johnson, W. C. & Aldridge, B. B. Types and functions of heterogeneity in mycobacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 529–541 (2022).

Dartois, V. A. & Rubin, E. J. Anti-tuberculosis treatment strategies and drug development: challenges and priorities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 685–701 (2022).

Gold, B. & Nathan, C. Targeting phenotypically tolerant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.tbtb2-0031-2016 (2017).

Ehrt, S., Schnappinger, D. & Rhee, K. Y. Metabolic principles of persistence and pathogenicity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 496–507 (2018).

Rittershaus, E. S. C. et al. A lysine acetyltransferase contributes to the metabolic adaptation to hypoxia in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 1495–1505.e3 (2018).

Baker, J. J., Dechow, S. J. & Abramovitch, R. B. Acid fasting: modulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism at acidic pH. Trends Microbiol. 27, 942–953 (2019).

Li, Y. Y. et al. Clinically relevant mutations of mycobacterial GatCAB inform regulation of translational fidelity. mBio 12, e0110021 (2021).

Lavin, R. C. & Tan, S. Spatial relationships of intra-lesion heterogeneity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis microenvironment, replication status, and drug efficacy. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010459 (2022).

Sebastian, J. et al. Origin and dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis subpopulations that predictably generate drug tolerance and resistance. mBio 13, e0279522 (2022).

Fauvart, M., De Groote, V. N. & Michiels, J. Role of persister cells in chronic infections: clinical relevance and perspectives on anti-persister therapies. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 699–709 (2011).

De Wet, T. J., Warner, D. F. & Mizrahi, V. Harnessing biological insight to accelerate tuberculosis drug discovery. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 2340–2348 (2019).

Mishra, R. et al. Targeting redox heterogeneity to counteract drug tolerance in replicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaaw6635 (2019).

Balaban, N. Q., Merrin, J., Chait, R., Kowalik, L. & Leibler, S. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science 305, 1622–1625 (2004).

Pontes, M. H. & Groisman, E. A. Slow growth determines nonheritable antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica. Sci. Signal. 12, eaax3938 (2019).

Mattioli, C. C. et al. Physiological stress drives the emergence of a Salmonella subpopulation through ribosomal RNA regulation. Curr. Biol. 33, 4880–4892 (2023).

Jani, C. et al. Regulation of polar peptidoglycan biosynthesis by Wag31 phosphorylation in mycobacteria. BMC Microbiol. 10, 327 (2010).

Yuichi, W. et al. Dynamic persistence of antibiotic-stressed mycobacteria. Science 339, 91–95 (2013).

Vaubourgeix, J. et al. Stressed mycobacteria use the chaperone ClpB to sequester irreversibly oxidized proteins asymmetrically within and between cells. Cell Host Microbe 17, 178–190 (2015).

Richardson, K. et al. Temporal and intrinsic factors of rifampicin tolerance in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 8302–8307 (2016).

Eskandarian, H. A. et al. Division site selection linked to inherited cell surface wave troughs in mycobacteria. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17094 (2017).

Logsdon, M. M. et al. A parallel adder coordinates mycobacterial cell-cycle progression and cell-size homeostasis in the context of asymmetric growth and organization. Curr. Biol. 27, 3367–3374.e7 (2017).

Baranowski, C. et al. Maturing Mycobacterium smegmatis peptidoglycan requires non-canonical crosslinks to maintain shape. eLife 7, e37516 (2018).

Aldridge, B. B. et al. Asymmetry and aging of mycobacterial cells lead to variable growth and antibiotic susceptibility. Science 335, 100–104 (2012).

Hesper Rego, E., Audette, R. E. & Rubin, E. J. Deletion of a mycobacterial divisome factor collapses single-cell phenotypic heterogeneity. Nature 546, 153–157 (2017).

Mukkayyan, N., Sharan, D. & Ajitkumar, P. A symmetric molecule produced by mycobacteria generates cell-length asymmetry during cell-division and thereby cell-length heterogeneity. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 1447–1454 (2018).

Botella, H. et al. Distinct spatiotemporal dynamics of peptidoglycan synthesis between Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. mBio 8, e01183-17 (2017).

Yamada, H. et al. Mycolicibacterium smegmatis, basonym Mycobacterium smegmatis, expresses morphological phenotypes much more similar to Escherichia coli than Mycobacterium tuberculosis in quantitative structome analysis and cryoTEM examination. Front Microbiol 9, 1992 (2018).

Klann, A. G., Belanger, A. E., Abanes-De Mello, A., Lee, J. Y. & Hatfull, G. F. Characterization of the dnaG locus in Mycobacterium smegmatis reveals linkage of DNA replication and cell division. J. Bacteriol. 180, 65–72 (1998).

Stephan, J. et al. The growth rate of Mycobacterium smegmatis depends on sufficient porin-mediated influx of nutrients. Mol. Microbiol. 58, 714–730 (2005).

Priestman, M., Thomas, P., Robertson, B. D. & Shahrezaei, V. Mycobacteria modify their cell size control under sub-optimal carbon sources. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 5, 64 (2017).

Garton, N. J. et al. Cytological and transcript analyses reveal fat and lazy persister-like bacilli in tuberculous sputum. PLoS Med. 5, e75 (2008).

Sarathy, J. P. & Dartois, V. Caseum: a niche for Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug-tolerant persisters. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33, e00159–19 (2020).

Larkins-Ford, J. et al. Systematic measurement of combination-drug landscapes to predict in vivo treatment outcomes for tuberculosis. Cell Syst. 12, 1046–1063.e7 (2021).

Yamada, H., Yamaguchi, M., Chikamatsu, K., Aono, A. & Mitarai, S. Structome analysis of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which survives with only 700 ribosomes per 0.1 fl of cytoplasm. PLoS ONE 10, e0117109 (2015).

Godin, M. et al. Using buoyant mass to measure the growth of single cells. Nat. Methods 7, 387–390 (2010).

Wang, P. et al. Robust growth of Escherichia coli. Curr. Biol. 20, 1099–1103 (2010).

Mir, M. et al. Optical measurement of cycle-dependent cell growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13124–13129 (2011).

Iyer-Biswas, S. et al. Scaling laws governing stochastic growth and division of single bacterial cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15912–15917 (2014).

Campos, M. et al. A constant size extension drives bacterial cell size homeostasis. Cell 159, 1433–1446 (2014).

Taheri-Araghi, S. et al. Cell-size control and homeostasis in bacteria. Curr. Biol. 25, 385–391 (2015).

Cermak, N. et al. High-throughput measurement of single-cell growth rates using serial microfluidic mass sensor arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 1052–1059 (2016).

Yu, F. B. et al. Long-term microfluidic tracking of coccoid cyanobacterial cells reveals robust control of division timing. BMC Biol. 15, 11 (2017).

Kar, P., Tiruvadi-Krishnan, S., Männik, J., Männik, J. & Amir, A. Distinguishing different modes of growth using single-cell data. eLife 10, e72565 (2021).

Cylke, A. & Banerjee, S. Super-exponential growth and stochastic size dynamics in rod-like bacteria. Biophys. J. 122, 1254–1267 (2023).

van Heerden, J. H., Berkvens, A., de Groot, D. H. & Bruggeman, F. J. Growth consequences of the inhomogeneous organization of the bacterial cytoplasm. eLife 13, RP99996 (2024).

Nordholt, N., van Heerden, J. H. & Bruggeman, F. J. Biphasic cell-size and growth-rate homeostasis by single Bacillus subtilis cells. Curr. Biol. 30, 2238–2247.e5 (2020).

Messelink, J., Meyer, F., Bramkamp, M. & Broedersz, C. P. Single-cell growth inference of Corynebacterium glutamicum reveals asymptotically linear growth. eLife 10, e70106 (2021).

Knapp, B. D. et al. Decoupling of rates of protein synthesis from cell expansion leads to supergrowth. Cell Syst. 9, 434–445.e6 (2019).

Pickering, M., Hollis, L. N., D’Souza, E. & Rhind, N. Fission yeast cells grow approximately exponentially. Cell Cycle 18, 869–879 (2019).

Scott, M., Gunderson, C. W., Mateescu, E. M., Zhang, Z. & Hwa, T. Interdependence of cell growth. Science 330, 1099–1102 (2010).

Lin, J. & Amir, A. Homeostasis of protein and mRNA concentrations in growing cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 4496 (2018).

Sukumar, N., Tan, S., Aldridge, B. B. & Russell, D. G. Exploitation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reporter strains to probe the impact of vaccination at sites of infection. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004394 (2014).

Santi, I. & McKinney, J. D. Chromosome organization and replisome dynamics in Mycobacterium smegmatis. mBio 6, e1004394 (2015).

Smeulders, M. J., Keer, J., Speight, R. A. & Williams, H. D. Adaptation of Mycobacterium smegmatis to stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 181, 270–283 (1999).

Odermatt, P. D. et al. Overlapping and essential roles for molecular and mechanical mechanisms in mycobacterial cell division. Nat. Phys. 16, 57–62 (2020).

Kieser, K. J. & Rubin, E. J. How sisters grow apart: mycobacterial growth and division. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 550–562 (2014).

Lord, S. J., Velle, K. B., Dyche Mullins, R. & Fritz-Laylin, L. K. SuperPlots: communicating reproducibility and variability in cell biology. J. Cell Biol. 219, e202001064 (2020).

Meniche, X. et al. Subpolar addition of new cell wall is directed by DivIVA in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E3243–E3251 (2014).

Kieser, K. J. et al. Phosphorylation of the peptidoglycan synthase PonA1 governs the rate of polar elongation in mycobacteria. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005010 (2015).

Hannebelle, M. T. M. et al. A biphasic growth model for cell pole elongation in mycobacteria. Nat. Commun. 11, 452 (2020).

Garcia-Heredia, A. et al. Peptidoglycan precursor synthesis along the sidewall of pole-growing mycobacteria. eLife 7, e37243 (2018).

Yang, X.-S. Introduction to Algorithms for Data Mining and Machine Learning 1st edn (eds Bentley, J. S. & Lutz. M.) Ch. 4 (Elsevier, 1st edition, 2019); https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817216-2.00011-9

Cooper, S. Distinguishing between linear and exponential cell growth during the division cycle: single-cell studies, cell-culture studies, and the object of cell-cycle research. Theor. Biol. Med. Model 3, 10 (2006).

Vandal, O. H., Nathan, C. F. & Ehrt, S. Acid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4714–4721 (2009).

Tan, S., Sukumar, N., Abramovitch, R. B., Parish, T. & Russell, D. G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis responds to chloride and pH as synergistic cues to the immune status of its host cell. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003282 (2013).

Gygli, S. M., Borrell, S., Trauner, A. & Gagneux, S. Antimicrobial resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: mechanistic and evolutionary perspectives. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41, 354–373 (2017).

Levien, E., Min, J., Kondev, J. & Amir, A. Non-genetic variability in microbial populations: survival strategy or nuisance? Rep. Prog. Phys. 84, 116601 (2021).

Lenski, R. E. Experimental evolution and the dynamics of adaptation and genome evolution in microbial populations. ISME J. 11, 2181–2194 (2017).

Kostinski, S. & Reuveni, S. Ribosome composition maximizes cellular growth rates in E. coli. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 28103 (2020).

Caspi, Y. Deformation of filamentous Escherichia coli cells in a microfluidic device: a new technique to study cell mechanics. PLoS ONE 9, e83775 (2014).

Li, H. et al. Adaptable microfluidic system for single-cell pathogen classification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 10270–10279 (2019).

James, B. W., Williams, A. & Marsh, P. D. The physiology and pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis grown under controlled conditions in a defined medium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88, 669–677 (2000).

Barczak, A. K. et al. In vivo phenotypic dominance in mouse mixed infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 192, 600–606 (2005).

Gill, W. P. et al. A replication clock for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 15, 211–214 (2009).

Amir, A. Is cell size a spandrel? eLife 6, e22186 (2017).

Feltz, C. J. & Miller, G. E. An asymptotic test for the equality of coefficients of variation from k populations. Stat. Med. 15, 647–658 (1996).

Maffeo, C. & Aksimentiev, A. Molecular mechanism of DNA association with single-stranded DNA binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 12125–12139 (2017).

Spenkelink, L. M. et al. Recycling of single-stranded DNA-binding protein by the bacterial replisome. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 4111–4123 (2019).

Eun, Y. J. et al. Archaeal cells share common size control with bacteria despite noisier growth and division. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 148–154 (2018).

Chung, E. S., Kar, P., Kamkaew, M., Amir, A. & Aldridge, B. B. Single-cell imaging of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell cycle reveals linear and heterogenous growth. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22930310 (2024).

Chung, E. S., Kar, P., Kamkaew, M., Amir, A. & Aldridge, B. B. Single-cell imaging of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell cycle reveals linear and heterogenous growth. GitHub https://github.com/pkar96/Mtb-growth (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Tan (Tufts University School of Medicine) for the generous gift of the CDC1551 SSB–GFP, smyc′::mCherry strain. B.B.A. was supported by the NIH (R01 AI143611-01). A.A. was supported by NSF CAREER (1752024), cofunded by the European Union (ERC, BIGR, 101125981) and the Clore Center for Biological Physics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S.C., P.K., B.B.A. and A.A. conceptualized the project, E.S.C. and M.K. conducted the experiments and time-lapse imaging annotation, and P.K. ran the mathematical analysis. E.S.C., P.K., B.B.A. and A.A. wrote the draft, and all authors reviewed and edited the paper. B.B.A. and A.A. acquired funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Single-cell traces of SSB-GFP localization (movie set A).

The distance between the x-axis and the black circle indicates cell length. Yellow circles indicate SSB-GFP foci. a-c, Cells with a cell cycle comprised of B-C-D periods. The duration of each period can vary between single cells. d,e, Cells with cell cycle comprised of B-C-D-E periods. Cells with an E period initiate another round of DNA replication before division. The daughter cells of this type of cell lack the B period and enters C directly. f, Example cell with a cell cycle comprising a C and D period. This type of cell cycle occurs in cells whose mother begins replication before division (E period). In cases where foci disappeared for a frame or two due to focus issues and then reappeared, we assumed replication continued until the last foci disappeared. g, Proportional distances between new pole or old pole and SSB foci. The left cartoon illustrates how the proportional distance between SSB and new pole or old pole is calculated. The green circle indicates the location of SSB foci. In each cell, the distance was measured when either one or two SSB foci were present. To calculate the proportional distance, the average distance from either the new or old pole was divided by the length of the cell (for cells with one SSB focus: proportional distance between new pole and SSB = a⁄b; for cells with two SSB foci: proportional distance between new pole and SSB = a⁄c, between old pole and near SSB = b⁄c). On the right, the circles represent the proportional distance between SSB foci and the indicated pole (cell numbers with one SSB focus = 363, cell numbers with two SSB foci = 139). The red horizontal lines mark the median value. Each dot represents a single cell from three biological replicates. P-value was calculated using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Species-specific growth characteristics in mycobacteria.

a, The average time and proportion of each cell cycle period (B: pre-replication, C: DNA replication, D: post-replication, E: new DNA replication after a D period but before division) are indicated. The BCG and M. smegmatis data are from a previous study25. b, Distributions of Lb, Ld, Td, and elongation speed are compared between Mtb (n = 363) and BCG (n = 74). The numbers above the plots and red horizontal lines indicate the median value for each sample. P-values were calculated with the two sided, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. The p-values for each comparison are 9.36*10−39, 8.66*10−39, 4.10*10−06, and 6.56*10−21, respectively. The BCG data are from a previous study25.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Growth characteristics of Mtb during the course of time-lapse imaging (movie set A).

The distributions of Lb and Ld, elongation speed, growth amount, and Td are compared between acc (n = 173) and alt (n = 130), respectively. Dots with green, orange, and gray indicate different biological replicates. Colored dots with black border indicate median values of single dots (single cells) in the same color. Horizontal lines mark the median value of a total population for each sample. P-values were calculated with a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Single cell growth in NETO, BEITO, and OETO (movie set B).

a and d represent single cells with NETO, b and e represent single cells with BEITO, and c and f represent single cells with OETO. d-f, The snapshots display the length grown at the old pole (green line) and the new pole (red line). The plots next to the snapshots illustrate the best fits for length growth vs. time trajectories. A linear fit best describes the old pole growth of cells (d) and (e), while a bilinear fit is preferred for the cell in (f) based on the \(\Delta {AIC}\) and \(\Delta {BIC}\) values. Regarding the new pole growth, a linear fit is preferred for cells (e) and (f), while a bilinear fit is preferred for cell (d).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Growth rate vs. age and elongation speed vs. age plots of each biological replicate (movie set A).

a-c, The binned data trend (blue dots) of growth rate \((\frac{1}{L}\frac{{dL}}{{dt}})\) vs. age plots are shown for three individual replicates of Mtb data (n = 125, 116, 122, respectively). The binned data trend decreases with age and is largely consistent with the predicted trend obtained using simulations of linear growth (red line). d-f, The binned data trend (blue dots) of elongation speed vs. age plot is shown for the three replicates of Mtb data. The binned data trend is constant consistent with the predicted trend obtained using linear growth simulations. The error bars are presented as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–6, Table 1, discussion and notes.

Supplementary Video 1

A video (video set A) using the Mtb CDC1551 strain harbouring the SSB–GFP reporter in unbuffered (pH ~6.8) standard growth medium supplemented with Middlebrook 7H9.

Supplementary Video 2

A video (video set B) using the FDAA pulse-labelled Mtb CDC1551 wild-type strain in neutral (pH 7.0) standard growth medium supplemented with Middlebrook 7H9.

Supplementary Video 3

A video (video set C) using the FDAA pulse-labelled Mtb CDC1551 wild-type strain in acidic (pH 5.9) standard growth medium supplemented with Middlebrook 7H9.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article