Abstract

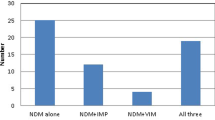

Carbapenems are last-resort antibiotics for treating bacterial infections. The widespread acquisition of metallo-β-lactamases, such as VIM-2, contributes to the emergence of carbapenem-resistant pathogens, and currently, no metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors are available in the clinic. Here we show that bacteria expressing VIM-2 have impaired growth in zinc-deprived environments, including human serum and murine infection models. Using transcriptomic, genomic and chemical probes, we identified molecular pathways critical for VIM-2 expression under zinc limitation. In particular, disruption of envelope stress response pathways reduced the growth of VIM-2-expressing bacteria in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we showed that VIM-2 expression disrupts the integrity of the outer membrane, rendering VIM-2-expressing bacteria more susceptible to azithromycin. Using a systemic murine infection model, we showed azithromycin’s therapeutic potential against VIM-2-expressing pathogens. In all, our findings provide a framework to exploit the fitness trade-offs of resistance, potentially accelerating the discovery of additional treatments for infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

RNA-seq data are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject PRJNA1054171 with the accession numbers SRR27256495, SRR27256494, SRR27256493, SRR27256492, SRR27256491 and SRR27256490. The genomic data for E. coli BW25113 referenced in this study are available at the European Nucleotide Archive under the accession number CP009273. In addition, the K. pneumoniae strain ATCC 43816 genome sequence is available in GenBank under BioProject PRJNA675363 with the accession number CP064352. Genomics source data have been deposited on Code Ocean86 (for genetic suppressors—Keio collection, https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.1737239.v1; for genetic enhancers—Keio collection, https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.7249224.v1; for genetic enhancers—CRISPRi collection, https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.7144620.v1). The data presented in Fig. 2a,c–g are provided in Supplementary Tables 1, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8, respectively. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The R script supporting the findings of this study is available on Code Ocean86 (for genetic suppressors—Keio collection, https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.1737239.v1; for genetic enhancers—Keio collection, https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.7249224.v1; for genetic enhancers—CRISPRi collection, https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.7144620.v1).

References

Bush, K. The importance of β-lactamases to the development of new β-lactams. in Antimicrobial Drug Resistance: Mechanisms of Drug Resistance (ed. Mayers, D. L.) 135–144 (Humana Press, 2009).

Pandey, N. & Cascella, M. Beta lactam antibiotics. StatPearls https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545311/ (2023).

Meletis, G. Carbapenem resistance: overview of the problem and future perspectives. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 3, 15–21 (2016).

King, A. M. et al. Aspergillomarasmine A overcomes metallo-β-lactamase antibiotic resistance. Nature 510, 503–506 (2014).

Brown, E. D. & Wright, G. D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature 529, 336–343 (2016).

Martin, J. K. et al. A dual-mechanism antibiotic kills gram-negative bacteria and avoids drug resistance. Cell 181, 1518–1532 (2020).

McLaughlin, M. et al. Correlations of antibiotic use and carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 5131–5133 (2013).

2021 Antibacterial Agents in Clinical and Preclinical Development: An Overview and Analysis (World Health Organization, 2022).

Everett, M. et al. Discovery of a novel metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor that potentiates meropenem activity against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e00074-18 (2018).

González-Bello, C., Rodríguez, D., Pernas, M., Rodríguez, Á. & Colchón, E. β-Lactamase inhibitors to restore the efficacy of antibiotics against superbugs. J. Med. Chem. 63, 1859–1881 (2020).

Wang, D. Y., Abboud, M. I., Markoulides, M. S., Brem, J. & Schofield, C. J. The road to avibactam: the first clinically useful non-β-lactam working somewhat like a β-lactam. Future Med. Chem. 8, 1063–1084 (2016).

Lomovskaya, O. et al. Vaborbactam: spectrum of beta-lactamase inhibition and impact of resistance mechanisms on activity in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e01443-17 (2017).

Mansour, H., Ouweini, A. E. L., Chahine, E. B. & Karaoui, L. R. Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam: a new carbapenem β-lactamase inhibitor combination. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 78, 674–683 (2021).

Lomovskaya, O. et al. QPX7728, an ultra-broad-spectrum β-lactamase inhibitor for intravenous and oral therapy: overview of biochemical and microbiological characteristics. Front. Microbiol. 12, 697180 (2021).

López, C., Ayala, J. A., Bonomo, R. A., González, L. J. & Vila, A. J. Protein determinants of dissemination and host specificity of metallo-β-lactamases. Nat. Commun. 10, 3617 (2019).

Meini, M.-R., González, L. J. & Vila, A. J. Antibiotic resistance in Zn(II)-deficient environments: metallo-β-lactamase activation in the periplasm. Future Microbiol. 8, 947–979 (2013).

González, J. M. et al. Metallo-β-lactamases withstand low Zn(II) conditions by tuning metal–ligand interactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 698–700 (2012).

González, L. J. et al. Membrane-anchoring stabilizes and favors secretion of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 516–522 (2016).

Meini, M.-R., Tomatis, P. E., Weinreich, D. M. & Vila, A. J. Quantitative description of a protein fitness landscape based on molecular features. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1774–1787 (2015).

González, L. J., Bahr, G., González, M. M., Bonomo, R. A. & Vila, A. J. In-cell kinetic stability is an essential trait in metallo-β-lactamase evolution. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 1116–1126 (2023).

Murdoch, C. C. & Skaar, E. P. Nutritional immunity: the battle for nutrient metals at the host–pathogen interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 657–670 (2022).

Côté, J. P. et al. The genome-wide interaction network of nutrient stress genes in Escherichia coli. mBio 7, e01714–e01716 (2016).

Velasco, E. et al. A new role for zinc limitation in bacterial pathogenicity: modulation of α-hemolysin from uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 8, 6535 (2018).

Liu, J. Z. et al. Zinc sequestration by the neutrophil protein calprotectin enhances Salmonella growth in the inflamed gut. Cell Host Microbe 11, 227–239 (2012).

Galani, I., Souli, M., Chryssouli, Z., Katsala, D. & Giamarellou, H. First identification of an Escherichia coli clinical isolate producing both metallo-β-lactamase VIM-2 and extended-spectrum β-lactamase IBC-1. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10, 757–760 (2004).

Maaroufi, R. et al. Occurrence of NDM-1 and VIM-2 co-producing Escherichia coli and OprD alteration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from hospital environment samples in northwestern Tunisia. Diagnostics 11, 1617 (2021).

Hernández-García, M. et al. Confronting ceftolozane-tazobactam susceptibility in multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales isolates and whole-genome sequencing results (STEP study). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 57, 106259 (2021).

Hernández-García, M. et al. WGS characterization of MDR Enterobacterales with different ceftolozane/tazobactam susceptibility profiles during the SUPERIOR surveillance study in Spain. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2, dlaa084 (2020).

Falco, A., Ramos, Y., Franco, E., Guzmán, A. & Takiff, H. A cluster of KPC-2 and VIM-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST833 isolates from the pediatric service of a Venezuelan hospital. BMC Infect. Dis. 16, 595 (2016).

Mohammad Ali Tabrizi, A., Badmasti, F., Shahcheraghi, F. & Azizi, O. Outbreak of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae harbouring blaVIM-2 among mechanically-ventilated drug-poisoning patients with high mortality rate in Iran. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 15, 93–98 (2018).

Vilacoba, E. et al. A blaVIM-2 plasmid disseminating in extensively drug-resistant clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 7017 (2014).

Ghaith, D. M. et al. First reported nosocomial outbreak of Serratia marcescens harboring blaIMP-4 and blaVIM-2 in a neonatal intensive care unit in Cairo, Egypt. Infect. Drug Resist. 11, 2211–2217 (2018).

Yan, J.-J., Ko, W.-C., Chuang, C.-L. & Wu, J.-J. Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in a university hospital in Taiwan: prevalence of IMP-8 in Enterobacter cloacae and first identification of VIM-2 in Citrobacter freundii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50, 503–511 (2002).

Porres-Osante, N. et al. First description of a blaVIM-2-carrying Citrobacter freundii isolate in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 6331–6332 (2014).

Matsumura, Y. et al. Genomic epidemiology of global VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 2249–2258 (2017).

Hong, D. J. et al. Epidemiology and characteristics of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Chemother. 47, 81–97 (2015).

Alcock, B. P. et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D690–D699 (2023).

Yonekawa, S. et al. Molecular and epidemiological characteristics of carbapenemase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in Japan. mSphere 5, e00490-20 (2020).

Laubacher, M. E. & Ades, S. E. The Rcs phosphorelay is a cell envelope stress response activated by peptidoglycan stress and contributes to intrinsic antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 190, 2065–2074 (2008).

Miot, M. & Betton, J.-M. Protein quality control in the bacterial periplasm. Microb. Cell Factories 3, 4 (2004).

Hews, C. L., Cho, T., Rowley, G. & Raivio, T. L. Maintaining integrity under stress: envelope stress response regulation of pathogenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 313 (2019).

Baba, T. et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008 (2006).

Rachwalski, K., Tu, M. M., Madden, S. J., Hansen, D. M. & Brown, E. D. A mobile CRISPRi collection enables genetic interaction studies for the essential genes of Escherichia coli. Cell Rep. Methods 4, 100683 (2024).

Klobucar, K., French, S., Côté, J.-P., Howes, J. R. & Brown, E. D. Genetic and chemical–genetic interactions map biogenesis and permeability determinants of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. mBio 11, e00161-20 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Increasing intracellular magnesium levels with the 31-amino acid MgtS protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 5689–5694 (2017).

Beard, S. J. et al. Evidence for the transport of zinc(II) ions via the pit inorganic phosphate transport system in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184, 231–235 (2000).

Gati, C., Stetsenko, A., Slotboom, D. J., Scheres, S. H. W. & Guskov, A. The structural basis of proton driven zinc transport by ZntB. Nat. Commun. 8, 1313 (2017).

Tam, C. & Missiakas, D. Changes in lipopolysaccharide structure induce the σE-dependent response of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1403–1412 (2005).

Konovalova, A. et al. Inhibitor of intramembrane protease RseP blocks the σE response causing lethal accumulation of unfolded outer membrane proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E6614–E6621 (2018).

Alba, B. M., Leeds, J. A., Onufryk, C., Lu, C. Z. & Gross, C. A. DegS and YaeL participate sequentially in the cleavage of RseA to activate the σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response. Genes Dev. 16, 2156–2168 (2002).

Bongard, J. et al. Chemical validation of DegS as a target for the development of antibiotics with a novel mode of action. ChemMedChem 14, 1074–1078 (2019).

Pogliano, J. et al. Aberrant cell division and random FtsZ ring positioning in Escherichia coli cpxA* mutants. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3486–3490 (1998).

Mathelié-Guinlet, M., Asmar, A. T., Collet, J.-F. & Dufrêne, Y. F. Bacterial cell mechanics beyond peptidoglycan. Trends Microbiol. 28, 706–708 (2020).

World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines—23rd List (World Health Organization, 2023).

Al-Marzooq, F., Ghazawi, A., Daoud, L. & Tariq, S. Boosting the antibacterial activity of azithromycin on multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli by efflux pump inhibition coupled with outer membrane permeabilization induced by phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 8662 (2023).

Farha, M. A. et al. Overcoming acquired and native macrolide resistance with bicarbonate. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 2709–2718 (2020).

Geddes, E. J., Li, Z. & Hergenrother, P. J. An LC–MS/MS assay and complementary web-based tool to quantify and predict compound accumulation in E. coli. Nat. Protoc. 16, 4833–4854 (2021).

Nicoloff, H., Gopalkrishnan, S. & Ades, S. E. Appropriate regulation of the σE-dependent envelope stress response is necessary to maintain cell envelope integrity and stationary-phase survival in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 199, e00089-12 (2017).

Moore, J. B., Blanchard, R. K. & Cousins, R. J. Dietary zinc modulates gene expression in murine thymus: results from a comprehensive differential display screening. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3883–3888 (2003).

Gammoh, N. Z. & Rink, L. Zinc in infection and inflammation. Nutrients 9, 624 (2017).

Galloway, S. P., McMillan, D. C. & Sattar, N. Effect of the inflammatory response on trace element and vitamin status. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 37, 289–297 (2000).

Lonergan, Z. R. & Skaar, E. P. Nutrient zinc at the host–pathogen interface. Trends Biochem. Sci. 44, 1041–1056 (2019).

Mojica, M. F., Bonomo, R. A. & Fast, W. B1-Metallo-beta-lactamases: where do we stand? Curr. Drug Targets 17, 1029–1050 (2016).

Sabath, L. D. & Abraham, E. P. Zinc as a cofactor for cephalosporinase from Bacillus cereus 569. Biochem. J. 98, 11C–13CC (1966).

Cheng, Z. et al. A single salt bridge in VIM-20 increases protein stability and antibiotic resistance under low-zinc conditions. mBio 10, e02412–e02419 (2019).

Tsuchido, T., VanBogelen, R. A. & Neidhardt, F. C. Heat shock response in Escherichia coli influences cell division. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 83, 6959–6963 (1986).

Vats, P., Shih, Y.-L. & Rothfield, L. Assembly of the MreB-associated cytoskeletal ring of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 170–182 (2009).

Mitchell, A. M. & Silhavy, T. J. Envelope stress responses: balancing damage repair and toxicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 417–428 (2019).

Nair, A. B. & Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 7, 27–31 (2016).

Souque, C., Escudero, J. A. & MacLean, R. C. Integron activity accelerates the evolution of antibiotic resistance. eLife 10, e62474 (2021).

Poirel, L. et al. Characterization of VIM-2, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-β-lactamase and its plasmid- and integron-borne gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 891–897 (2000).

Simner, P. J. et al. An NDM-producing Escherichia coli clinical isolate exhibiting resistance to cefiderocol and the combination of ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam: another step towards pan-β-lactam resistance. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 10, ofad276 (2023).

Cox, G. et al. A common platform for antibiotic dereplication and adjuvant discovery. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 98–109 (2017).

Chung, C. T., Niemela, S. L. & Miller, R. H. One-step preparation of competent Escherichia coli: transformation and storage of bacterial cells in the same solution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 2172–2175 (1989).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 525–527 (2016); 34, 888 (2016).

Ihaka, R. & Gentleman, R. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5, 299–314 (1996).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Keseler, I. M. et al. EcoCyc: fusing model organism databases with systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D605–D612 (2013).

Karp, P. D. Pathway databases: a case study in computational symbolic theories. Science 293, 2040–2044 (2001).

Karp, P. D. et al. Pathway Tools version 19.0 update: software for pathway/genome informatics and systems biology. Brief. Bioinform. 17, 877–890 (2016).

Datsenko, K. A. & Wanner, B. L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6640–6645 (2000).

Depardieu, F. & Bikard, D. Gene silencing with CRISPRi in bacteria and optimization of dCas9 expression levels. Methods 172, 61–75 (2020).

French, S. et al. A robust platform for chemical genomics in bacterial systems. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 1015–1025 (2016).

Das, I., Burch, R. E. & Hahn, H. K. Effects of zinc deficiency on ethanol metabolism and alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase activities. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 104, 610–617 (1984).

Seamless sharing and peer review of code. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 773 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Wright from McMaster University for bacterial strains from the Institute for Infectious Disease Research clinical collection. We also thank the Centre for Microbial Chemical Biology at McMaster University, specifically N. Henriquez for LC–MS/MS. This research was supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair award, a Foundation Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CHIR; FRN 143215) and a grant from the Ontario Research Fund (RE09-047) to E.D.B. M.M.T. was supported by a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGS-D). D.C. was supported by a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGS-M) and an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. M.E.S. was supported by a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGS-M). J.M.S. was supported by The Weston Family Foundation and the CIHR. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.T. conceived the research, designed and carried out experiments and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. L.A.C. and R.G. assisted in the animal experiments. K.R. assisted with the design of the mobile plasmids and the execution of the genomic studies. S.F. performed the microscopy analysis. D.C. aided in the analysis of the RNA-seq dataset. C.R.M. assisted with manuscript editing. M.E.S. and F.W. acquired MIC data. J.M.S. assisted with data interpretation and manuscript editing. E.D.B. conceived the research and assisted with data interpretation and manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 VIM-2 expression reduces K. pneumoniae growth in zinc-limited human serum.

(a, b) CFU/mL of viable cell counts of K. pneumoniae expressing VIM-2 (blue) and the empty vector (dark red) in 50% human serum (a, n = 5 for all time points except for 12 hours (n = 3)) and 50% human serum supplemented with 10 µM ZnSO4 (b, n = 6 for all time points except for 12 hours (n = 3) and 24 hours (n = 5)) over 24 hours. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Overexpression of degP is associated with improved growth of carbapenem-resistant bacteria.

(a) mRNA levels of degP compared in wildtype and mutant Keio strains, transcript levels were normalized to the level of rrsE. The dotted line delineates degP levels in wildtype (WT), at a fold change of 1. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (WT, n = 7; ∆waaP, n = 4; ∆gmhA, n = 7; ∆atpD, n = 6; ∆hldE, n = 3; ∆waaF; n = 6; ∆yiiS, n = 2; n is defined as biological replicates and each biological replicate consists of at least two technical replicates). Statistical significance was determined using a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons, relative to the WT (∆waaP, *P = 0.039; ∆gmhA, ****P < 0.0001; ∆atpD, *P = 0.013; ∆hldE, ****P < 0.0001; ∆waaF, ****P < 0.0001; ∆yiiS, ***P = 0.0005). (b) Protein levels of DegP from whole cell lysates in wildtype and mutant Keio strains. RNA Polymerase subunit α served as a loading control. Data is a representative blot of three biological replicates. (c) mRNA levels of degP compared in K. pneumoniae carrying the empty vector (Empty; n = 3) and expressing VIM-2 (VIM-2; n = 3) following growth in vivo. Samples were collected 7 hours post-infection from the blood. Transcript levels were normalized to the level of recA. Data are mean ± s.e.m, and each point represents an individual mouse. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test, **P < 0.01 (t = 6.727, df=4).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Inhibiting DegS is a viable strategy to treat VIM-2-expressing K. pneumoniae in vivo.

Viable cell counts of K. pneumoniae carrying the empty vector (Empty) or expressing VIM-2 (VIM-2) in the (a) blood, (b) kidney, and (c) liver. Each strain was treated with a vehicle (grey; blood n = 5,5; kidney n = 7,6, liver n = 7,7) or 50 mg/kg of the DegS inhibitor (orange; blood n = 4,8, kidney n = 6,8, liver n = 6,10) one hour after infection. Each point represents an individual mouse. The centre line delineates the median, the box limits mark the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers depict the range. CFU were enumerated at 6 hours post-infection. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney test with Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. The mouse infection model was repeated on three separate days.

Extended Data Fig. 4 VIM-2 expression impairs cell septation under zinc-limited conditions.

(a, b) Fluorescent microscopy of wildtype (WT) E. coli, E. coli carrying the empty vector, and E. coli expressing VIM-2 in (a) M9 minimal media and (b) M9 minimal media supplemented with 10 µM ZnSO4. Cells are stained with FM 4-64. Scale bar = 10 µm. (c) Fluorescent microscopy of wildtype (WT) K. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae carrying the empty vector, and K. pneumoniae expressing VIM-2 in M9 minimal media. Cells are stained with FM 4-64. Scale bar = 10 µm. Microscopy was repeated in duplicate to ensure consistent phenotypes.

Extended Data Fig. 5 A22 selectively targets VIM-2 expressing K. pneumoniae in human serum.

Competitive index (CI) for the co-inoculation of K. pneumoniae expressing VIM-2 and the empty vector in 50% human serum at 24 hours in the presence of two-fold dilutions of A22 (0 µg/mL, n = 7; 2 µg/mL, n = 2; 4 µg/mL, n = 4; 8 µg/mL, n = 5; 16 µg/mL n = 3; 32 µg/mL, n = 4). Data are mean ± s.e.m. The dotted line represents a CI of 1.

Extended Data Fig. 6 VIM-2 expression disrupts the integrity of the outer membrane.

N-Phenly-1-naphthylamine (NPN) uptake of E. coli expressing VIM-2 (light blue) relative to the empty vector control (red) in M9 minimal media (n = 6,6), M9 minimal media supplemented with 10 µM ZnSO4 (n = 5,6), and M9 minimal media supplemented with 10 µM MgSO4 (n = 4,6). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided unpaired t-test with false discovery rate correction, applying the two-stage linear step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli, ***P < 0.001 (M9: t = 11.35, df=10; M9 + Zn2+: t = 1.333, df = 9; M9 + Mg2+: t = 26.20, df=8).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Azithromycin is a viable treatment option for VIM-2-expressing K. pneumoniae in vivo.

Viable cell counts of K. pneumoniae carrying the empty vector (Empty) or expressing VIM-2 (VIM-2) in the (a) spleen, (b) kidney, and (c) liver. Each strain was treated with a vehicle (grey; spleen n = 11,12; kidney n = 7,11, liver n = 11,12) or 10 mg/kg of azithromycin (purple; blood n = 6,6, kidney n = 4,5, liver n = 6,6) one hour after infection and 3.5 hours post-infection. Each point represents an individual mouse. The centre line delineates the median, the box limits mark the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers depict the range. CFU were enumerated at 6 hours post-infection. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney test with Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Clinical isolate of P. aeruginosa naturally expressing VIM-2 displays a fitness cost in zinc-limited environments.

(a) Growth kinetics of a clinical P. aeruginosa isolate that naturally expresses VIM-2 (GDW923) and (b) PAO1, a control strain, in M9 minimal media (n = 5,2; light blue) and M9 minimal media supplemented with 10 µM of ZnSO4 (n = 6,2; dark blue). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Data is normalized to OD600 of each strain at 48 hours and fit to Gompertz growth. (c) CFU/mL of viable cell counts of P. aeruginosa expressing VIM-2 and PAO1, a VIM-2 negative strain, in 50% human serum (n = 3,4; light blue) and 50% human serum supplemented with 10 µM ZnSO4 (n = 3,4; dark blue) at 24 hours. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided unpaired t-test with false discovery rate correction, applying the two-stage linear step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli, **P < 0.01 (GDW923: t = 5.050, df=4; PAO1: t = 0.4850, df=6). (d) Fluorescent microscopy of a clinical P. aeruginosa isolate that naturally expresses VIM-2 (GDW923) and PAO1, a VIM-2 negative strain, in M9 minimal media and M9 minimal media supplemented with 10 µM ZnSO4. Cells are stained with FM 4-64. Scale bar = 10 µm. (e) NPN uptake of P. aeruginosa expressing VIM-2 (GDW923) in M9 minimal media (n = 6,6) and M9 minimal media supplemented with 10 µM ZnSO4 (n = 6,6). A carbapenem-susceptible P. aeruginosa strain (PA01) is used as a control. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided unpaired t-test with false discovery rate correction, applying the two-stage linear step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli, ****P < 0.0001 (GDW923: t = 9.809, df=10; PAO1: t = 3.137, df=10).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Subinhibitory concentrations of meropenem sensitize clinical isolates to azithromycin and elevate VIM-2 expression.

(a) MIC of azithromycin against a panel of P. aeruginosa clinical isolates harbouring VIM-2 and PAO1, a VIM-2 negative strain in M9 minimal media and M9 minimal media supplemented with ½ MIC of meropenem. (b) mRNA levels of vim-2 compared in clinical isolates in M9 minimal media (CDC 230, n = 3; CDC 242, n = 3; CDC 254, n = 3; CDC 255, n = 6) and M9 minimal media supplemented with ½ MIC of meropenem (CDC 230, n = 4; CDC 242, n = 3; CDC 254, n = 5; CDC 255, n = 5). Transcript levels were normalized to the level of 16S rRNA. The dotted line delineates vim-2 levels in CDC 230, at a fold change of 1. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided unpaired t-test with false discovery rate correction, applying the two-stage linear step-up method by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli, *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0011 (CDC 230: t = 3.682, df=5; CDC 242: t = 2.809, df=4; CDC 254: t = 1.380, df=6; CDC 255: t = 9.033,df=9).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Azithromycin reduces the bacterial load of a clinical P. aeruginosa isolate naturally expressing VIM-2 in vivo.

Log10 reduction of viable cell counts P. aeruginosa CDC 243 in the spleen, kidney, and liver treated with 50 mg/kg of azithromycin one-hour post-infection relative to vehicle-treated mice (n = 4). Mice also received a treatment of 100 mg/kg of ZnSO4 every four hours or a vehicle (n = 4). Each point represents an individual mouse. The centre line delineates the median, the box limits mark the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers depict the range. CFUs were enumerated at 18 hours post-infection. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Spleen: t = 4.982, df=6; Kidney: t = 4.745, df=6; Liver: t = 3.003, df=6).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5 and Tables 2, 4, 6, 8, 11 and 12.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 10.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, M.M., Carfrae, L.A., Rachwalski, K. et al. Exploiting the fitness cost of metallo-β-lactamase expression can overcome antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens. Nat Microbiol 10, 53–65 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01883-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01883-8

This article is cited by

-

Zinc-dependent β-lactam resistance at a cost

Nature Microbiology (2025)

-

Dissecting pOXA-48 fitness effects in clinical Enterobacterales using plasmid-wide CRISPRi screens

Nature Communications (2025)

-

In vitro activity of the novel β-lactamase inhibitor FL058 combined with meropenem against KPC- or NDM-producing enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2025)