Abstract

Optical quasiparticles called magnetic excitons recently emerged in magnetic van der Waals materials. Akin to the highly effective strategies developed for electrons, the strong interactions of these excitons with the spin degree of freedom may provide innovative solutions for long-standing challenges in optics, such as steering the flow of energy and information. Here we demonstrate the transport of excitons by spin excitations in the van der Waals antiferromagnetic semiconductor CrSBr. Our observations reveal ultrafast, nearly isotropic exciton propagation, substantially enhanced at the Néel temperature, transient contraction and expansion of exciton clouds at low temperatures and superdiffusive behaviour in bilayer samples. These signatures largely defy description by commonly known exciton transport mechanisms. Instead, we attribute them to magnon currents induced by laser excitation. We propose that the drag forces exerted by these currents can effectively imprint characteristic properties of spin excitations onto the motion of excitons. The universal nature of the underlying magnon–exciton scattering promises the driving of excitons by magnons in other magnetic semiconductors and even in non-magnetic materials by proximity in heterostructures, merging the rich physics of magnetotransport with optics and photonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

More than three decades ago, the giant magnetoresistance effect1,2 demonstrated the extensive potential of controlling electrons using the spin degree of freedom in solids. The profound impact of this discovery on science and technology spawned the field of spintronics and ultimately came to play an important role in modern electronics. Now, reports of excitons in magnetic van der Waals crystals3,4,5,6,7,8 and their interactions with magnetic spin order raise the question whether similar developments are on the brink of transforming optics and photonics. High-speed propagation, anomalous dispersion, exceptional coherence and thermopower9,10,11,12,13,14 can be extremely attractive features of spin excitations (magnons and paramagnons) in this context. This promise, however, rests on the expectation that the recently reported coupling of excitons and magnons15,16,17,18 can indeed be leveraged to control19,20,21 the movement of quasiparticles in solids.

A key material to explore this question is the van der Waals magnetic semiconductor CrSBr (refs. 22,23). At low temperatures, CrSBr exhibits strong magnetization along the in-plane b axis that alternates between layers in the out-of-plane c axis (Fig. 1b). Moderate magnetic fields are already sufficient to switch the antiferromagnetic (AFM) ground state into a ferromagnetic (FM) configuration. As the temperature rises, an increasingly larger number of thermal magnons progressively suppresses long-range magnetic order until the material becomes paramagnetic (PM) above the Néel temperature of TN = 132 K (refs. 22,23,24). Moreover, a local temperature gradient generates a flux of incoherent magnons25. Most importantly, CrSBr hosts tightly bound excitons that interact strongly with light17, are tunable by magnetic fields6,26,27 and couple to both coherent and incoherent magnons15,16,17,18. This renders it an ideal platform to study the impact of magnon currents on excitonic motion.

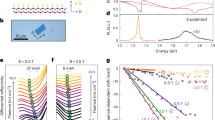

a, PL spectrum and the derivative of reflectance contrast (with a fit curve; Methods) recorded at T = 4 K. The dashed line and the Gaussian profile mark the optical signature of the fundamental exciton X0 transition in CrSBr (refs. 6,28). b, Schematic of the CrSBr structure in the AFM phase and the optical injection of propagating excitons in the experiments. c, PL cross-section profiles along b measured at 4 K and 125 K. The PL is integrated in energy and in time from 0 to 150 ps after pulsed excitation. The arrows represent the standard deviation σ extracted from Gaussian fits. Inset: corresponding time dependence of the relative Δσ2(t). The solid lines are linear fits to the data. d, Blue circles, temperature dependence of the effective diffusion coefficient D*, extracted by evaluating \({D}^{* }=\frac{1}{2} \partial \Delta {\sigma }^{2}/\partial t\) over the first 80 ps along the b axis. The blue line is a guide to the eye. The solid and dotted orange lines show the expected classical diffusion of excitons along the a and b axes. Labels and the black dashed line mark the TN and the AFM–PM phase transition, respectively. The error bars indicate the statistical error of the linear fit of σ2(t) to obtain D*. Data in c and d are obtained under a fluence of 390 μJ cm−2 at 1.61-eV excitation energy, corresponding to an exciton density in the range of 1012 cm−2 per layer. Similar results, obtained at a smaller fluence for an excitation energy of 1.77 eV close to the B-exciton resonance, are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. a.u., arbitrary units.

Here we demonstrate the transport of excitons in CrSBr and present a series of experimental signatures implicating the drag of excitons by magnons. For up to tens of picoseconds after the excitation by a short light pulse, excitons are observed to move remarkably fast. Their propagation correlates with the magnetic phase and reaches a maximum at TN. Corresponding effective diffusion coefficients are as high as 150 cm2 s−1, exceeding expectations from classical exciton diffusion by orders of magnitude. Moreover, for the majority of excitation conditions, the exciton propagation is quasi-isotropic in the van der Waals plane, in stark contrast to the highly anisotropic exciton effective masses dictated by the electronic dispersion of CrSBr. Instead, it matches the nearly isotropic in-plane propagation of thermal magnons and their group velocities. Finally, at low temperatures and excitation densities, we observe a complete reversal of the exciton propagation direction, from expansion to contraction, and find ultrafast, superdiffusive behaviour in bilayers (2L) with effective velocities reaching 41 km s−1 within the first 15 ps.

Magnetically correlated exciton transport

The photoluminescence (PL) and reflectance contrast spectra of a 9-nm-thick (about 10L; Supplementary Section 2) crystal in Fig. 1a are typical for the few-nanometre-thick CrSBr flakes investigated in our study. The PL peak at 1.366 eV matches the well-known resonance of CrSBr excitons (X0) in the reflectance6,17,26,28, whereas additional low-energy features in PL are attributed to either phonon sidebands29 or surface-like states30. In light of the results presented below, we note that neither the effective diffusion coefficients nor the emission lifetimes we obtain from our measurements vary considerably across the emission spectrum (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 14). The use of such very thin crystals, with purely excitonic optical responses, avoids contributions from self-hybridized polaritons17. This allows us to measure the actual propagation of excitons with a transient optical microscopy technique by imaging the spectrally integrated cross-section of the entire PL emission as a function of time and space onto a fast streak camera detector following the excitation by a sub-1-ps short laser pulse (Methods)31. Temporally and spectrally integrated spatial profiles of the 10L PL signal, presented for 4 K and 125 K (Fig. 1c), already show that the exciton propagation length in CrSBr is temperature dependent. Even more pronounced are the differences in the time-resolved expansions of the exciton cloud, presented in the inset as a relative increase in Δσ2(t), which represents the relative change of the mean squared displacement32.

For a quantitative analysis, we evaluate the effective exciton diffusion coefficient, defined as \({D}^{* }=\frac{1}{2} \partial \Delta {\sigma }^{2}/\partial t\), during the first 80 ps, as a function of the lattice temperature for an excitation fluence of 390 μJ cm−2, which corresponds to an estimated initial exciton density of about 2 × 1012 cm−2 per layer (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Section 3). As demonstrated in Fig. 1d, the exciton propagation exhibits a pronounced maximum near TN, the critical point of the magnetic phase transition. Among the observed phenomena characteristic for the spatiotemporal dynamics of excitons in CrSBr (Extended Data Fig. 3), the temperature dependence of D* is particularly intriguing because of its striking similarity with the nearly diverging magnetic susceptibility at TN (ref. 24). This correlation suggests that the transport of excitons is not determined by classical diffusion or hopping as in the majority of semiconductors. Instead, the coupling of excitons to the spin degree of freedom seems to play a major role.

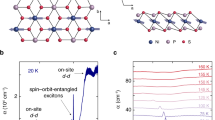

This notion is strongly supported by two key findings of our study. First, at T = TN, exciton transport is almost isotropic with respect to the a and b axes, as shown by the symmetric PL shape and similar density-dependent traces of Δσ2(t) (Fig. 2a,b). This observation is in stark contrast with the strongly anisotropic dispersion of excitons and electrons6,26,33,34 and the anisotropic electric conductivity35 in CrSBr, but in good agreement with recent studies reporting nearly isotropic magnon transport15,18. Our calculation of the magnon dispersion (Fig. 2e) further shows that magnons are not only much more isotropic but also much heavier than excitons. Second, the time-resolved expansion of the exciton cloud (Fig. 2b) strongly depends on the excitation fluence and can, thus, become exceptionally fast. Most values of D* we obtain from evaluating the dynamics in the first 20 ps are orders of magnitude larger than those expected from a classical diffusion model. The latter estimates exciton diffusion coefficients to be in the range of 1 cm2 s−1, or below, based on the exciton masses in the a and b directions and scattering rates obtained from the temperature-dependent linewidths of the X0 peak (Supplementary Section 5A and Fig. 1d (orange lines)).

a, Top: spatial PL profile recorded at TN = 132 K under a fluence of 3,100 μJ cm−2. Broadening along the a and b directions is indicated by the blue and red arrows, respectively. The dashed circles mark the σ values extracted from the Gaussian fits of the PL and laser profiles. Bottom: spatial profile of the excitation laser. b, Time and fluence dependencies of Δσ2(t) recorded at TN along the a and b directions (Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The lines are linear fits to the data during the first 25 ps. Insets: the axis of transport measurement. c, Position dependence of X0 emission under an excitation fluence of 260 μJ cm−2 (top) and 3,100 μJ cm−2 (bottom), corresponding to the estimated exciton densities between 1.1 × 1012 and 1.3 × 1013 cm−2 per layer, respectively. The sample temperature was nominally 4 K, but spectral shifts in the region of laser excitation locally indicate an effective increase in temperature due to excitation (Extended Data Fig. 5). The laser profile is shown by the grey line. d, Schematic illustrating an incoherent magnon flux jmag (blue) propagating away from the excitation region, dragging excitons (red and blue circles) along. Pulsed laser excitation is indicated by the red line. e, Calculated magnon dispersion. Compared with exciton masses from ref. 26, magnons are substantially heavier than excitons; magnon-to-exciton mass ratios are 38 and 7 along the b and a directions. Ma and Mb denote the masses of magnons along the a- and b-directions, respectively; m0 is the free electron mass. The solid and dashed lines represent two branches that are very close in energy (Supplementary Section 6).

Magnon–exciton drag

Besides diffusion, few other processes are known to impact exciton transport. Among them, exciton–exciton repulsion can be excluded due to its strong dependence on the effective mass and expected anisotropy36. Exciton–exciton annihilation31,37 may potentially play a role, as it can lead to an apparent, density-dependent broadening of the spatial exciton distribution. However, the annihilation coefficients we obtain and the resulting contributions to the effective diffusion coefficient substantially underestimate our observations for the majority of the studied experimental conditions with the exception of room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 9). Most importantly, one would not expect this process to be enhanced specifically at TN. Due to its general importance for other two-dimensional semiconductors, we provide an extensive discussion on exciton–exciton annihilation in Supplementary Section 5B.

The position dependence of the X0 emission peak at T = 4 K, where the reduction in linewidth compared to that at elevated temperatures resolves much smaller spectral shifts (Fig. 2c), reveals that considerable amounts of excess energy are released in the CrSBr crystal following optical excitation. Especially under a higher fluence, sizable spectral shifts within the excitation area strongly indicate local heating by several tens of kelvins, as shown by the analysis in Extended Data Fig. 5. Thus, not only excitons but also an imbalance in the spatial occupation of phonons and magnons is created by the optical excitation38, resulting in a flux of all quasiparticles away from the excitation region39,40. Although neither the pure Seebeck drift of excitons themselves41 nor their coupling to phonons42,43 can explain the peak we observe at TN. Thermal magnon currents, as we discuss below, are key for understanding the transport of excitons in this material instead. It is also worth noting that the high sensitivity of PL to exciton populations in the first tens of picoseconds, the larger fluence and the absence of external fields contrast the nanosecond propagation dynamics of coherent magnons studied in recent pump–probe experiments15,16,18.

We propose that a mutual drag between excitons and thermal magnon currents emerges directly from their scattering. Our theoretical analysis (Supplementary Section 7) demonstrates that the underlying interaction is distinct from the magnon–exciton coupling recently observed in a canted spin state15. Because of their larger effective mass and occupation, magnons are able to substantially accelerate excitons through scattering, analogous to the effects enhancing the thermal transport of electrons in magnetic materials44. This process of magnon–exciton drag qualitatively explains the key signatures of our experiments. First of all, the steady increase in the population of thermal magnons on approaching TN enhances the magnon flux11,45,46 and, thus, maximizes the magnon–exciton drag effect, which is in good agreement with the pronounced maximum of D* we observe at TN. This is also confirmed by a recent study on CrSBr (ref. 25) reporting a maximum of the electronic Seebeck coefficient near TN. Even at temperatures above TN, substantial drag is expected from the short-range magnetic correlations called paramagnons47, evidenced in the magnetometry measurements of CrSBr far beyond TN (ref. 24).

A more detailed description of this process is presented in Supplementary Section 7. It estimates that the nearly isotropic dispersion15 and propagation18 of magnons with non-zero momentum may overcome the strong anisotropy of the electronic dispersion when the scattering rates are sufficiently high. In this case, the stream of heavy, rapidly propagating magnons essentially carries the excitons along (Fig. 2d). This also explains why, at elevated temperatures, anisotropic exciton transport is only observable at very low excitation densities compared with the studied regime (Extended Data Fig. 6) and why the differences are much smaller than expected from theory. Finally, we note that the average expansion of excitons we observe is in overall good agreement with the typical propagation velocities of magnons, which are in the range of approximately a few kilometres per second in CrSBr. Altogether, the magnon–exciton drag effect provides a suitable framework for capturing key signatures of the exciton transport observed in our experiments across a broad range of temperatures.

Low-temperature transport

To complete the experimental picture, we now present two particularly striking phenomena observed at low temperatures. First, at 4 K, the exciton distribution is not expanding; it appears to be contracting over time (Fig. 3a,b), which can be resolved because the absolute width of the PL spot still exceeds the optical diffraction limit (Extended Data Fig. 7). The observed contraction is also very fast. Depending on the chosen model, we either obtain an average inward velocity of –3 km s−1 or D* = –13 cm2 s−1. Contraction is not too common for excitons48,49 but seems to be ubiquitous in CrSBr, independent of the layer number. Since the effect is more prominently observed along the b axis, exciton transport at 4 K is anisotropic in the a–b plane. Increasing the fluence or the sample temperature, however, turns the anisotropic contraction into a positive, nearly isotropic expansion of the exciton cloud (Figs. 3c and 2b).

a, Streak camera image from 10L recorded at T = 4 K showing space- and time-resolved exciton PL normalized to the maximum at each time step. Exciton transport measured along the b direction under a laser excitation fluence of 155 μJ cm−2. The dashed lines are a guide to the eye. b, Line fit of Δσ2(t) extracted from a corresponds to an effective diffusion coefficient of D* = −(13 ± 1) cm2 s−1. Inset: image denoting the axis of transport measurement. c, Dependence of D* on temperature (grey squares) and excitation fluence (4 K; blue circles) shows a transition from exciton cloud contraction to expansion. The excitation fluence for the temperature series was 310 μJ cm−2. Inset: excitation fluence dependence of D* measured at 4 K in the 10L crystal for transport along the a and b axes. The solid lines approximate a linear fluence and temperature dependence. d, Magnon dispersion of the lowest branch for small magnon momenta Q. e, Corresponding magnon group velocities. norm., normalized.

The fact that the group velocity of magnons with very small energies and momenta can become negative in CrSBr (ref. 18; Fig. 3d,e) suggests that a scenario in which excitons are dragged by magnons with predominantly antiparallel phase and group velocities is possible. A simplified, semianalytical model presented in Supplementary Section 7 indeed shows that the primary excitation of such magnons at low temperatures and fluences may allow magnons propagating away from the excitation region to scatter excitons backwards, causing a contraction of the exciton cloud. By contrast, at elevated temperatures or fluences, the thermal occupation of magnons with higher energies and momenta, and positive group velocity, favours forward scattering and regular expansion (Fig. 3c). This also motivates a selective excitation of magnons with negative and positive group velocities18 for future experiments in this unusual propagation regime.

The second striking observation at low temperatures is a remarkably fast expansion of the excitonic emission in 2L crystals spanning hundreds of nanometres within picoseconds (Fig. 4a). The broadening is continuous and well resolved in the first 15 ps after the excitation and appears to be only limited by the fast decay of excitons (Fig. 4b). Most interestingly, in this time window, Δσ2(t) does not increase linearly but exhibits a superlinear behaviour. The observed expansion law, Δσ2 ∝ tα, with values of α between 1.3 ± 0.1 and 2.1 ± 0.3 obtained from fits, is a hallmark of exciton superdiffusion32. Similar features are consistently observed along the a direction, for both AFM and FM phases, and in other 2L samples (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 10 and Methods), and yet are absent in a nearby 3L crystal. For completeness, we note that monolayer PL signals were too small to draw reliable conclusions.

a, Streak camera image recorded at T = 4 K showing space- and time-resolved exciton PL normalized to the maximum at each time step. It shows a rapid expansion in a 2L crystal for FM configuration (Methods). The excitation fluence is set to 310 μJ cm−2 and the PL is measured along the b axis. The dashed lines are guides to the eye. b, PL transients of the spatially integrated emission. The grey dashed line represents the detector response to an ~140-fs short excitation pulse. The PL lifetime extracted from the monoexponential fits shown in the figure increases with the layer number from 3 ps in 2L (AFM and FM) to 4 ps in 3L and 11 ps in 10L. c, Corresponding Δσ2(t) measured for a 2L crystal (AFM and FM) and a 3L (AFM) crystal. The obtained effective propagation velocity of excitons in 2L (FM) is 41 km s−1 (Extended Data Fig. 7). d, PL spectra recorded at 20 K and 60 K. e, Δσ2(t) fitted by Δσ2 ∼ tα with α > 1 for 20 K and α = 1 for 60 K. Inset: data for 60 K in the first 10 ps.

Superdiffusion generally indicates coherent transport. However, the ballistic motion of excitons themselves seems an unlikely explanation, since excitons are expected to be frequently scattered by phonons and magnons on these timescales. Besides, experimental transport signatures in 2L crystals otherwise match the contraction, nearly isotropic propagation and pronounced fluence dependence of thicker samples (Extended Data Fig. 9 and 10). We, thus, speculate that the superdiffusive behaviour results from the enhanced interactions of excitons with ballistically propagating magnon waves. This is supported by the fact that the expected transition towards regular diffusion (Δσ2 ∝ t) is observed at temperatures of around 60 K (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 1). The origin of superdiffusion in 2L and the large effective velocities that exceed the velocity of long-range magnon transport reported for bulk CrSBr (refs. 15,18) is not clear at this stage. Nevertheless, we note that the properties of excitons and magnons in ultrathin crystals could differ from those of bulk (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). In particular, phenomena related to surface30,50,51 and superluminal-like effects12, as well as a stronger role of phonons52,53, could contribute to the ultrafast dynamics of excitons and magnons in 2L crystals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, exciton transport in ultrathin crystals of the layered antiferromagnet CrSBr is very fast, fluence dependent and peaks at TN. It features both expansion and contraction and can become superdiffusive in bilayer crystals. Although common transport mechanisms fail to describe these findings, the scattering of excitons by a flux of thermal magnons is proposed to drive exciton transport. For sufficiently strong interactions, excitons no longer move independently inside a stream of heavy magnons; they are effectively carried by the magnon current. The fact that magnons can exhibit much longer coherence times and lengths than excitons, and may be excited electrically, highlights the considerable potential of exciton–spin interactions to imprint magnon transport properties onto the typically slow motion of excitons. It might further be possible to drive excitons even in non-magnetic semiconductors by both coherent and incoherent magnon currents using proximity effects in heterostructures. Altogether, these results are highly promising for the realization of efficient magnetic control of optical quasiparticles, an encouraging new direction for fundamental research on correlated exciton–spin systems and, more broadly, energy and information transport in solids.

Methods

Crystal growth and sample fabrication

CrSBr bulk single crystals were synthesized by the chemical vapour transport method described in ref. 26. From these bulk crystals, thin flakes with typical lateral extensions of several tens of micrometres were mechanically exfoliated directly from tape onto standard SiO2/Si substrates with a SiO2 thickness of 285 nm. After the transfer, samples were stored under vacuum conditions. For the experiments, they were mounted either directly onto the cold finger of a continuous-flow He cryostat, or on top of a small disc magnet with in-plane magnetization providing a permanent magnetic field of ~0.2 T, which was then glued onto the cold finger. We estimate an accuracy of ±10° for the alignment of CrSBr crystals with respect to the in-plane magnetization axis of the magnet and an accuracy of ±5° for their alignment relative to the detector slit. Due to a reduction in the saturation field, 2L crystals placed on top of the disc magnet allow us to study exciton transport in the FM phase inside our cryostat (Fig. 4 shows the results).

Optical spectroscopy and time-resolved microscopy

Few-layer crystals with lateral extensions of at least several micrometres were preselected by optical microscopy. Their layer number was determined by optical contrast and confirmed by atomic force microscopy. Before measuring the exciton dynamics, each flake was characterized by reflectance and PL spectroscopy. For reflectance, we used the attenuated output of a spectrally broadband tungsten halogen lamp, focused to a spot size of about 2.0 μm by a ×60 glass-corrected microscope objective (numerical aperture, 0.7). Spectra measured on top of the bare SiO2/Si substrate were used as a reference for the CrSBr reflectance spectra and analysed by the transfer-matrix method calculating the absorption spectrum based on a small set of Lorentz oscillators.

For transient PL microscopy, we used ultrashort (~140-fs) linearly polarized optical pulses from a Ti:sapphire laser tuned to a photon energy of 1.61 eV, or to 1.77 eV where specified. The laser was focused to a spot size of 0.8 μm by a ×60 glass-corrected objective. For each flake, the linear polarization of the laser was aligned parallel to the crystallographic b axis; no polarization-selective optics were used for the detection of emission. The PL was spectrally filtered to remove the laser excitation before being directed into the spectrometer, where it was either spectrally dispersed by a grating or imaged by a silver mirror. The signal was detected by a charge-coupled device and by a streak camera to acquire time-integrated and time-resolved data, respectively. We estimate the accuracy of D* values determined by our experiment to be ±0.1 cm2 s−1.

In our experiments, the variance σ of the PL spot in the first one or two picoseconds is typically ~0.3 μm larger than the size of the laser spot. This could result from differences in the excitation and detection wavelengths, chromatic aberration of the imaging system and potential ultrafast, subpicosecond propagation processes that are beyond the resolution of the streak camera detector.

Data availability

The main datasets generated and analysed in this study are available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17542127 (ref. 54). All other data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001) Fe/(001) Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472–2475 (1988).

Binasch, G., Grünberg, P., Saurenbach, F. & Zinn, W. Enhanced magnetoresistance in layered magnetic structures with antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange. Phys. Rev. B 39, 4828–4830 (1989).

Seyler, K. L. et al. Ligand-field helical luminescence in a 2D ferromagnetic insulator. Nat. Phys. 14, 277–281 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Direct photoluminescence probing of ferromagnetism in monolayer two-dimensional CrBr3. Nano Lett. 19, 3138–3142 (2019).

Kang, S. et al. Coherent many-body exciton in van der Waals antiferromagnet NiPS3. Nature 583, 785–789 (2020).

Wilson, N. P. et al. Interlayer electronic coupling on demand in a 2D magnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 20, 1675–1680 (2021).

Birowska, M., Junior, P. E. F., Fabian, J. & Kunstmann, J. Large exciton binding energies in MnPS3 as a case study of a van der Waals layered magnet. Phys. Rev. B 103, L121108 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Photoluminescence path bifurcations by spin flip in two-dimensional CrPS4. ACS Nano 16, 16385–16393 (2022).

Barman, A. et al. The 2021 magnonics roadmap. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33, 413001 (2021).

Lebrun, R. et al. Tunable long-distance spin transport in a crystalline antiferromagnetic iron oxide. Nature 561, 222–225 (2018).

Tu, S. et al. Record thermopower found in an IrMn-based spintronic stack. Nat. Commun. 11, 2023 (2020).

Lee, K. et al. Superluminal-like magnon propagation in antiferromagnetic NiO at nanoscale distances. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1337–1341 (2021).

Hortensius, J. et al. Coherent spin-wave transport in an antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 17, 1001–1006 (2021).

Wei, X.-Y. et al. Giant magnon spin conductivity in ultrathin yttrium iron garnet films. Nat. Mater. 21, 1352–1356 (2022).

Bae, Y. J. et al. Exciton-coupled coherent magnons in a 2D semiconductor. Nature 609, 282–286 (2022).

Diederich, G. M. et al. Tunable interaction between excitons and hybridized magnons in a layered semiconductor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 23–28 (2023).

Dirnberger, F. et al. Magneto-optics in a van der Waals magnet tuned by self-hybridized polaritons. Nature 620, 533–537 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Dipolar spin-wave packet transport in a van der Waals antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 20, 794–800 (2024).

Unuchek, D. et al. Room-temperature electrical control of exciton flux in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 560, 340–344 (2018).

Dong, Y. et al. Fizeau drag in graphene plasmonics. Nature 594, 513–516 (2021).

Tulyagankhodjaev, J. A. et al. Room-temperature wavelike exciton transport in a van der Waals superatomic semiconductor. Science 382, 438–442 (2023).

Göser, O., Paul, W. & Kahle, H. Magnetic properties of CrSBr. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 92, 129–136 (1990).

Telford, E. J. et al. Layered antiferromagnetism induces large negative magnetoresistance in the van der Waals semiconductor CrSBr. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003240 (2020).

Long, F. et al. Intrinsic magnetic properties of the layered antiferromagnet CrSBr. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 222401 (2023).

Canetta, A. et al. Impact of spin-entropy on the thermoelectric properties of a 2D magnet. Nano Lett. 24, 6513–6520 (2024).

Klein, J. et al. The bulk van der Waals layered magnet CrSBr is a quasi-1D material. ACS Nano 17, 5316–5328 (2023).

Tabataba-Vakili, F. et al. Doping-control of excitons and magnetism in few-layer CrSBr. Nat. Commun. 15, 4735 (2024).

Meineke, C. et al. Ultrafast exciton dynamics in the atomically thin van der Waals magnet CrSBr. Nano Lett. 24, 4101–4107 (2024).

Lin, K. et al. Strong exciton-phonon coupling as a fingerprint of magnetic ordering in van der Waals layered CrSBr. ACS Nano 18, 2898–2905 (2024).

Shao, Y. et al. Magnetically confined surface and bulk excitons in a layered antiferromagnet. Nat. Mater. 24, 391–398 (2025).

Kulig, M. et al. Exciton diffusion and halo effects in monolayer semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 207401 (2018).

Ginsberg, N. S. & Tisdale, W. A. Spatially resolved photogenerated exciton and charge transport in emerging semiconductors. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 71, 1–30 (2020).

Bianchi, M. et al. Paramagnetic electronic structure of CrSBr: comparison between ab initio GW theory and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 107, 235107 (2023).

Bianchi, M. et al. Charge transfer induced Lifshitz transition and magnetic symmetry breaking in ultrathin CrSBr crystals. Phys. Rev. B 108, 195410 (2023).

Wu, F. et al. Quasi-1D electronic transport in a 2D magnetic semiconductor. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109759 (2022).

Vögele, X., Schuh, D., Wegscheider, W., Kotthaus, J. & Holleitner, A. Density enhanced diffusion of dipolar excitons within a one-dimensional channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 126402 (2009).

Kumar, N. et al. Exciton-exciton annihilation in MoSe2 monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 89, 125427 (2014).

Kirilyuk, A., Kimel, A. V. & Rasing, T. Ultrafast optical manipulation of magnetic order. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2731 (2010).

Au, Y. et al. Direct excitation of propagating spin waves by focused ultrashort optical pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 097201 (2013).

An, K. et al. Magnons and phonons optically driven out of local equilibrium in a magnetic insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 107202 (2016).

Perea-Causín, R. et al. Exciton propagation and halo formation in two-dimensional materials. Nano Lett. 19, 7317–7323 (2019).

Bulatov, A. E. & Tikhodeev, S. G. Phonon-driven carrier transport caused by short excitation pulses in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 46, 15058–15062 (1992).

Glazov, M. M. Phonon wind and drag of excitons in monolayer semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 100, 045426 (2019).

Blatt, F., Flood, D., Rowe, V., Schroeder, P. & Cox, J. Magnon-drag thermopower in iron. Phys. Rev. Lett. 18, 395 (1967).

Qiu, Z. et al. Spin-current probe for phase transition in an insulator. Nat. Commun. 7, 12670 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Spin Seebeck effect from antiferromagnetic magnons and critical spin fluctuations in epitaxial FeF2 films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 217204 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. Paramagnon drag in high thermoelectric figure of merit Li-doped MnTe. Sci. Adv. 5, eaat9461 (2019).

Ziegler, J. D. et al. Fast and anomalous exciton diffusion in two-dimensional hybrid perovskites. Nano Lett. 20, 6674–6681 (2020).

Beret, D. et al. Nonlinear diffusion of negatively charged excitons in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 107, 045420 (2023).

Chen, Y.-J. et al. Group velocity engineering of confined ultrafast magnons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 267201 (2017).

Ye, C. et al. Layer-dependent interlayer antiferromagnetic spin reorientation in air-stable semiconductor CrSBr. ACS Nano 16, 11876–11883 (2022).

Liu, H. & Shen, K. Spin wave dynamics excited by a focused laser pulse in antiferromagnet CrSBr. Phys. Rev. B 110, 024424 (2024).

Bae, Y. J. et al. Transient magnetoelastic coupling in CrSBr. Phys. Rev. B 109, 104401 (2024).

Dirnberger, F. Exciton transport driven by spin excitations in an sntiferromagnet. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17542127 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the DFG via SFB 1277 (project B05, Project-ID: 314695032), the Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence on Complexity and Topology in Quantum Matter (ct.qmat) (EXC 2147, Project-ID 390858490) and the Emmy Noether Program (F.D., Project-ID 534078167) is gratefully acknowledged. A.C. acknowledges funding from ERC through CoG CoulENGINE (GA number 101001764). Z.S. was supported by ERC-CZ programme (project LL2101) from the Ministry of Education Youth and Sports (MEYS) and by the Advanced Multiscale Materials for Key Enabling Technologies project, supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic. Project no. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004558, Co-funded by the European Union and by the project Advanced Functional Nanorobots (reg. no. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/0000444 financed by the EFRR). Z.A.I. gratefully acknowledges support from the BASIS foundation. A.K. acknowledges financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) via Spin+X TRR 173-268565370 (project A13), the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation – AEI Grant CEX2018-000805-M (through the Maria de Maeztu Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D) and grant RYC2021-031063-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/50110001 1033 and European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.D. and A.C. conceived the experimental idea. F.D. and S.T. performed the experiments. S.T. fabricated the samples and F.D. analysed the data. K.M. and Z.S. provided the bulk crystals. M.M.G., A.K. and Z.A.I. provided theoretical support. The paper was written by F.D. and A.C. with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Nanotechnology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Exciton transport at 4 K measured in 10L for the full spectrum (unfiltered) and for the X0 peak (filtered).

a Spectrally filtered (red) PL spectrum of the 10L flake compared to the unfiltered (grey) spectrum. Shaded areas indicate the spectral cut-off of the filters. Both spectra are normalized to the maximum intensity of the full spectrum. b Variation of the mean squared displacement, Δσ2(t) = σ2(t) − σ2(0), obtained along the b–axis for the full spectrum and the filtered spectrum under 310 and 2450 μJ/cm2 excitation fluence. c Excitation fluence dependence of D* for both cases determined by evaluating the first 30 ps.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Calculated optical absorption and exciton density in the 10L crystal.

a Reflectance contrast spectrum measured at 4 K is fitted by a Lorentz oscillator model to calculate the absorption spectrum. Dashed line indicates the excitation energy of the optical pulses used to study exciton transport. b Excitation fluence and exciton and photon density for 1% absorption. Color coding of circles matches that of Fig. 2 and others.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Temperature dependence of spatio-temporal exciton dynamics.

a Exciton transport length l determined by \(l=\sqrt{2{D}^{* }\tau }\). b Exciton lifetime τ determined from single exponential fits of the spatially integrated exciton decay measured for different temperatures (cf. discussion in Section S10). c Effective exciton propagation velocity, v = Δσ(t)/t, evaluated from a linear fit of Δσ(t) over the first 20 ps after excitation (cf. also Extended Data Fig. 7). Error bars indicate the statistical error of the Δσ(t) fit. All data obtained under an excitation fluence of 390 μJ/cm2.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Exciton transport dynamics in 10L measured under resonant excitation of the B-exciton at 1.77 eV.

a Fluence dependence of the mean squared displacement, Δσ2(t), recorded at T = 4 K. b Fluence dependence of the effective diffusion coefficient obtained under 1.77 eV (red) and 1.61 eV (blue) excitation energies. c Temperature dependence of the effective diffusion coefficient measured with a fluence of 20 μJ/cm2 for the excitation photon energy of 1.77 eV. Solid red line is a guide to the eye. The inset illustrates how a temperature-dependent decrease of the absorption coefficient, α(T), indicated by the blue dashed line, can shift the maximum of D* towards lower temperatures. Error bars indicate the statistical error of the Δσ2(t) line fit.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Estimated increase of the local sample temperature under pulsed optical excitation.

a Left: PL emission of 10L as a function of temperature recorded under 310 μJ/cm2 fluence. Right: Same PL but as a function of excitation fluence at 4 K. Red circle and black marked spot indicate the full size of the PL emission spot and the center of the diffraction-limited PL spectra taken for data analysis. b Overlaid temperature and fluence dependence of the X0 emission energy at nominally 4 K determined in a. Inset shows a larger range of the temperature dependence. c Interpolated excitation-induced linear increase in temperature ΔT.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Signatures of anisotropic exciton transport.

Variation of the mean squared displacement, Δσ2(t), measured along a and b in 10L at 300 K for a small fluence, compared to the studied regime throughout the main manuscript, of 55 μJ/cm2 corresponding to exciton density of about 2 × 1011 cm−2 per layer. Error bars indicate the statistical error of the Δσ2(t) line fit.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Effective exciton velocity determined from transport measurements.

Exemplary measurement of σ(t) for a 10L and 310 μJ/cm2, b 10L and 3,100 μJ/cm2, c 2L and 310 μJ/cm2 illustrating the estimation of exciton propagation velocities as v = Δσ/Δt. Note that similar values can be found from a linear fit of σ(t) for t ≲ 15 − 20 ps. The values of σ obtained when imaging the laser (green dots) directly onto the streak camera do not change with time and are close to 0.4 μm. All data recorded at T = 4 K. Error bars indicate the statistical error of the Gauss fit.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Exciton transport in 10L along a and b at 4 K, 132 K, and 300 K.

a, Relative mean squared displacement, Δσ2(t), measured for different excitation fluence. Solid lines indicate the linear fits to obtain the values D* shown in Fig. S9. b Effective diffusion coefficients D* obtained from the data in a. Error bars indicate the statistical error of the Δσ2(t) line fit.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Exciton transport at 4 K in a 11L crystal.

a Exciton transport measured along the a–direction for 155 (yellow) and 3,100 (black) μJ/cm2. b Exciton transport measured along b for the full spectrum (unfiltered) and for the X0 peak (filtered). Both measurements were recorded with an excitation fluence of 310 μJ/cm2 and evaluated during the first 35 ps.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Exciton transport in 2L and other few-layer crystals at 4 K.

a Left: Schematic of the sample chip mounted on top of a small disk magnet with in-plane magnetization. Right: Optical microscope image of a 2L and a 3L crystal on the chip, which is glued onto the magnet such that the b–axis of the crystals aligns with the magnetization axis with an estimated precision of ± 10∘. b PL emission of the 2L crystal when the chip is mounted together with the magnet (red), or directly on top of the cold finger of the cryostat (blue). The spectral shift of the PL indicates a field-induced transition of the magnetic order into an FM state6. c Integrated PL signal of the 2L crystal (B = 0, AFM) shows only a weak dependence on excitation energy. d Fluence dependence of Δσ2(t) measured along the b–axis of the 2L crystal for 30 (orange), 55 (yellow), 150 (light blue), 310 (dark blue) μJ/cm2 in the AFM phase without the magnet at B=0. Dashed lines are guides to the eye. Inset: Δσ2(t) measured along a and b–axis in the FM phase on top of the magnet (B∥b) with 310 μJ/cm2. e,f Analogous to a,b on a second sample. g PL emission of a 1L and a 4L crystal when the chip is mounted together with the magnet (red), or directly on top of the cold finger of the cryostat (blue), illustrating the lack of energy shifts, as expected51. h Measurement of Δσ2(t) along the b–axis of a 2L (blue) and a 4L (orange) crystal for 500 μJ/cm2 on top of the magnet. The magnetic configuration is FM for the 2L crystal but because of the larger switching field required remains AFM for the 4L crystal. Dashed lines are guides to the eye. Inset: Magnified view of the negative transport measured in the 4L crystal. All data recorded at 4 K.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–10 and Figs. 1–15.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dirnberger, F., Terres, S., Iakovlev, Z.A. et al. Exciton transport driven by spin excitations in an antiferromagnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 21, 65–70 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02068-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02068-y