Abstract

Vortex knots have been seen decaying in many physical systems. Here we describe topologically protected vortex knots, which remain stable and undergo fusion and fission and conserve a topological invariant. The host medium, a chiral nematic liquid crystal, exhibits intrinsic chirality of molecular alignment, whereas cores of the vortex lines are structurally achiral regions in which a molecular twist cannot be defined. We can reversibly switch between fusion and fission of these vortex knots by applying electric pulses. This reveals the physical embodiments of concepts in knot theory, such as connected sums of knots and band surgeries. Our findings demonstrate the interplay of chirality effects at hierarchical levels from constituent molecules to the host medium and the energetically stable chiral vortex knots. This emergent physical behaviour may enable applications in electro-optics and photonics in which such fusion and fission processes of vortex knots can be used for controlling light.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Lord Kelvin’s attempts to develop physics models of chemical elements led to the modern-day knot theory1,2,3,4, a branch of pure mathematics, as well as to concepts of chirality and topology that play essential roles across the entire nature’s hierarchy, from elementary particles to soft, biological and quantum matter and to cosmology5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Fascinating experimental analogues of Kelvin’s vortex knot models of atoms were recently studied in common media like water12, but complex knots were found to decay to simpler counterparts and disappear after a series of reconnections of the vortex lines, so far finding no technological utility. On the other hand, liquid crystals (LCs) are known for their widespread applications, ranging from information displays to soft robotics and biodetection18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. However, their technological utility mainly relies on the continuous deformations of the orientational order of rod-like molecules in response to fields and other stimuli20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, even though topological defects are often used in some functionality designs, like mechanical actuation, guided nanoscale self-assembly and beamsteering19,23,28,29. At the same time, recent developments in nematic colloids and chiral LCs allowed for controllably realized closed loops and knots of vortex lines and particle-like topological solitons stabilized by chirality in the bulk of chiral media10,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Among them are the so-called ‘heliknotons’10, particle-like solitons that contain knotted vortex lines with structurally achiral core regions in which the twist cannot be defined, which can be referred to as ‘dischiralation’ vortex lines, in analogy to dislocations and disclinations in ordered media in which positional and orientational order is disrupted, respectively. However, the possibilities of using external stimuli for inducing fusion, fission and various reconnections of such topological objects, including inter-transformations between distinct states, as well as the dynamics of such processes have not been studied, although the control of particle-induced knots of disclination defects by laser tweezers was demonstrated32. Could the electric switching of such fascinating topological objects further enhance the vast electro-optic technological potential of LCs, in addition to providing vivid demonstrations and experimental tests of the mathematical knot theory at work? Towards this goal, we explore how low-voltage electric fields can guide controlled transformations of stable Kelvin-atom-like vortex knots in chiral LCs through fusion, fission and more complex relinking of knots.

Fission and fusion of atoms release massive amounts of energy, whereas the net total number of nucleons, protons and neutrons is conserved. Anyons in quantum computing40, skyrmions in optics41, and many other particles and topological quasiparticles can exhibit similar processes, but they are hidden from direct experimental observations and often difficult to control. We describe how topologically protected vortex knots in the chiral LC medium undergo directly observable reconnections and conserving integer-valued topological invariants, mimicking nuclear fusion and fission. Much like in subatomic systems, our soft-matter analogues of fusion and fission always lead to a lower energy of the final state. Interestingly, pulses of electric field can controllably alter the energetics of these states and sequentially fuse or split the same particle-like vortex knots, which would be impossible to achieve with subatomic-physics counterparts of our knotted particle-like objects. The facile control of such localized knotted structures in the chiral LC’s helical axis field promises knot-theory-guided photonic and electro-optic applications and unconventional computation, as well as data storage and spintronics applications for similar knots in magnetic systems9,10,11, in addition to providing insights into topologically analogous phenomena in fields ranging from cosmology to particle physics.

Electric-pulse-controlled interactions between knots

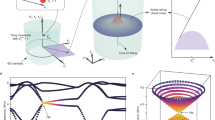

Our chiral nematics are confined in a geometry similar to that of electro-optic devices and displays22,24 (Fig. 1a–c), where the chiral LC is sandwiched between transparent indium tin oxide electrodes, to which a 1-kHz alternating-current voltage is applied. Far away from the knots, the helical axis field χ(r), around which molecules twist, is spatially uniform and orthogonal to confining substrates. Localized vortex knots in χ(r), regions in which the directionality of twist cannot be defined, are obtained by locally melting and quenching the LC using laser tweezers incorporated into an inverted microscope imaging setup. These localized knots are the so-called heliknotons, topological solitons with the hopfion topology in the material director field n(r) (Fig. 1d,e), but exhibiting singular vortex lines in χ(r) (Fig. 1b)10. Due to the dielectric coupling between the electric field and spatially localized n(r) and χ(r), the structure of heliknotons strongly depends on the magnitude of the applied voltage, expanding (shrinking) with increasing (reducing) voltage. The ensuing stability of different knotted structures at lower or higher voltages enables reversible transformations between them, allowing us to finely tune vortex knot interactions, reconnections and complexity via applying electrical pulses or a continuously changing voltage.

a, LC cell geometry with indium-tin-oxide-coated substrates, allowing the application of a tunable voltage to a sample containing vortex knots, where each separate closed-loop component in the schematic is differently coloured. b, Schematic of a vortex knot with the helical axis field \({\bf{\chi }}({\bf{r}})\) cross-sections depicting the local \({\bf{\chi }}({\bf{r}})\) field around the vortex at position \({\bf{r}}\). c, Schematic showing that \({\bf{\chi }}({\bf{r}})\) is the helical axis field around which the LC molecules and director field n(r) twist. d, Twist in the vectorized director field n(r) in the cross-section of a small part of the heliknoton (left) and the corresponding helical axis field \({\bf{\chi }}({\bf{r}})\) (right). The red circle indicates a –1/2 dischiralation region in the vortex knot’s cross-section. e, Hopfion topology of the heliknoton in n(r): preimages in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) (and \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{3}\)) correspond to distinct points in \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\), which form interlinked closed loops coloured by their orientation on \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\), as indicated by the dashed double arrows.

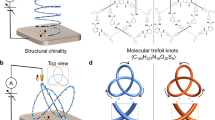

Although the connected sum of knots is a pure mathematical concept of reconnecting strands of two different knots through the so-called band surgery operation (Fig. 2a), similar reconnections can also emerge in biological contexts42, preserving the number of under/overcrossings within the ensuing composite knot. Our vortex knots with disrupted twisting in their cores (Fig. 2b) commonly also exhibit more complex types of fusion, reconnecting simultaneously at two sites of the interacting knots (Fig. 2c–g and Supplementary Video 1). The vortex lines forming the knots can have locally defined winding numbers of 1/2 or –1/2 (Fig. 2c,g), characterizing the local cross-sections of these defects, where the winding numbers quantify the angle by which χ(r) rotates around the vortex line when one navigates around its core once, divided by 2π. During the interaction, fragments of vortex lines of opposite winding number (±1/2) annihilate simultaneously at the two sites, effectively leading to two band surgeries (Fig. 2c–g). Such transformations first lead to a two-component link and then, with the subsequent reconnections, to a four-component link (Fig. 2c–g). To gain insights into how these transformations take place in our chiral nematic system, we visualize the smoothly vectorized n(r) with the help of its colour-coded order-parameter space, the two-sphere \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\) (Fig. 2d,e). This analysis reveals that n(r) stays continuous during such reconnections as the knots approach and fuse, having cores of merging vortex lines exhibit locally the same n(r) orientation. To reveal the behaviour of singular χ(r) during reconnection, we also visualize regions with strong bend and splay distortions in χ(r) (Fig. 2f,g). This reveals the fine details of the local annihilation of opposite-winding-number vortex line fragments, resulting in the reconnection, where the ±1/2 winding number of a given vortex fragment is encoded in the splay–bend pattern (Fig. 2f,g).

a, Connected sum of two trefoil knots. b, Schematic of a dischiralation vortex line with the core in the form of a region in which the helical axis field \({\bf{\chi }}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\) is singular (undefined) within a chiral LC. The top inset shows the local \({\bf{\chi }}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\) and the molecular twist at a point corresponding to the single black double arrow in a neighbourhood of the vortex line. c, Schematic of the vortex reconnections between the vortex knots of two heliknotons, where the grey and black segments indicate +1/2 and –1/2 vortex line fragments, respectively. The dashed red lines represent the locations of the corresponding cross-sections of \({\bf{\chi }}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\) depicted in planes perpendicular to the local vortex cores. The red circles highlight regions of reconnection progressing from left to middle; additional intra-heliknoton reconnections transform the dischiralation vortex knots depicted in the middle-to-right schematics. d, Two heliknotons undergoing a paired reconnection event, transforming from two trefoils (frame one) to multicomponent links (frames 3–5) coloured according to the director orientation shown in e. The red circles highlight regions in which reconnections progress through the intermediate formation of vertices of a four-valent graph, in the process indicated in c. e, Colour-mapping scheme of the vectorized director orientation n(r) based on the \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\) sphere (top left), where all the possible orientations of the unit vector are uniquely represented by the colours, as illustrated for the helical structure (top right). In the flattened version of the coloured unit sphere (bottom), the arrows show the directions of increasing azimuthal and polar angles describing the orientations of n(r), where the white centre corresponds to the north pole and black periphery denotes the south pole of \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\). f, Reconnections (shown in d) visualized with ribbons of splay and bend, where the dual-band and tri-band ribbons distinguish between the +1/2 and –1/2 winding numbers of dischiralation lines, respectively. Positive splay and bend regions of deformed χ(r) are shown in blue and the negative counterparts, in yellow, as depicted in g. Cross-sectional slices show the local χ(r) orientation and regions of strong splay and bend, both within their actual locations in the sample and as separate enlarged subpanels in the insets below and above. g, Schematic of the χ(r) orientation and the corresponding splay–bend geometry and the colour scheme for each dischiralation local structure type. Reconnections in d and f were initiated by reducing the voltage from 2.8 V (first three frames) to 2 V (last two frames) in a 20-μm-thick cell with an LC pitch of 5 μm. Supplementary Video 1 shows the corresponding dynamics.

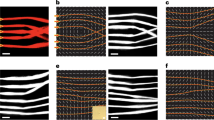

Polarizing optical microscopy (POM), coupled with numerical POM and free-energy modelling of the system (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video 2), reveals how the fusion of individual heliknotons progresses upon changing the applied voltage. The evolution of the separation vector (Fig. 3e) tracks the dynamics of heliknotons as they fuse together. The relinking pathways extracted from the experimental images and from the energy-minimizing evolution of the n(r) and χ(r) fields closely match (Fig. 3f,g and Supplementary Video 3). Interestingly, relinking, both within an individual heliknoton and between an interacting pair, can be driven along different kinetic pathways to yield complex knots (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Figs. 1–6), which can be understood in terms of possible band surgeries between the vortex line segments within individual knots or their pairs. In addition to the various types of double reconnection (Figs. 2–4), the reconnections representing more classical analogues of mathematical ‘connected sum of knots’ (Fig. 2a) are observed when heliknotons approach each other with the separation vector parallel to the far-field helical axis χ0 (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Video 4), which can be induced by subsecond pulses of the electric field. The relinking response times \({\tau }_{{\mathrm{a}}}\) and \({\tau }_{{\mathrm{o}}}\), defined as times needed for the fusion- or fission-type knot relinking to occur after the electric field is turned on or off, respectively, also occur in the subsecond range (Fig. 5b). Relinking times for double reconnection and reconnections of vortex lines within individual heliknotons are also characterized by times in the subsecond-to-second range, although somewhat longer pulses are typically needed to prompt these topological transformations (Fig. 5c,d and Supplementary Video 5). The response times can be tuned by controlling the electric field pulse amplitude, where \({\tau }_{{\mathrm{a}}}\) (\({\tau }_{{\mathrm{o}}}\)) can be shortened by increasing (reducing) the strength of the pulse (Extended Data Fig. 7). Although the band surgeries associated with knot transformations are classified as incoherent3,43,44,45 in nature in most cases, the examples shown in Fig. 5a,b can be considered as physical manifestations of the mathematically coherent (preserving orientation) band surgery2,3, with oriented constituent vortex knots undergoing fusion.

a–d, POM time series showing an initial array of six vortex knots after they are perturbed from the initial equilibrium configuration by changing voltage (a); three heliknotons fuse while three others remain individualized (b); the fused trimer hybridizes with one more heliknoton to form a tetramer, alongside two individual heliknotons (c); the remaining two individual heliknotons fuse to form the final configuration of a dimer (right) next to a tetramer (left) (d). Scale bars, 10 μm. The black double arrows show the orientation of crossed polarizers. The bottom-right insets are the corresponding numerically simulated POMs. Angle \(\psi\) defines the relative in-plane angle between the long axes of two interacting heliknotons. Sample thickness d = 16 μm and pitch p = 6.9 μm; the applied voltage U = 1.7 V in a and U = 2.1 V in b–d. Temporal progression is shown by arrows between the frames, with the elapsed time marked on them. Supplementary Video 1 shows the corresponding dynamics. e, Relative heliknoton–heliknoton positions and the visualization depicting the orientation parameters (\({\theta}_{\mathrm{el}},{\phi}\)) defined relative to the inter-heliknoton separation vector \({{\bf{r}}}_{\mathrm{s}}\) and the uniform far-field helical background of the sample. f,g, Experimental (f) and numerically simulated (g) trajectories of the separation vector for the two far-right trefoils in a–d. The knot insets in f (visualized with the help of KnotPlot freeware52) show the simplified vortex knot topology at the beginning, middle and end of the interaction process. The experimental and simulated dependencies are coloured based on the elapsed time according to the colour scheme shown in f. The schematic of the insets in f have each closed-loop components represented by different colours. The colours of the knot insets in g represent the director orientations in the non-singular cores of vortices, according to the scheme shown in Fig. 2e. The corresponding dynamics are shown in Supplementary Video 3.

a, Band surgery schematics of the admissible reconnections that occur within a single heliknoton. b, Band surgery schematics of the observed trefoil–trefoil reconnections. The annotations connect the schematics to transformations demonstrated in Figs. 2 and 3. The black-filled circles along the diagonal abbreviate alternative combinatorial reconnection pathways, which could be obtained by choosing different reconnection sites along the upper and lower branches, respectively. The grey (black) fragments within the knots denote +1/2 (–1/2) vortex fragments (Fig. 2c). Surgeries within heliknotons are coloured in blue, whereas inter-heliknoton reconnections are coloured in green. The blue-shaded (green-shaded) regions indicate an active reconnection pathway within (between) heliknotons corresponding to four-valent vertices (Fig. 2a, middle). KnotPlot-visualized52 insets show the simplified representations of fused vortex knots after reconnections. The arrows indicate reversible pathways induced by changing the applied voltage. Although different pathways can be preselected by means like relative initial positions, sample thickness, pitch, surface boundary conditions, voltage amplitude, frequency and various kinetic voltage-driving schemes, the detailed explorations of such means of control is beyond the present study’s scope.

a, Reconnection of trefoils coloured according to the scheme shown in Fig. 2e, with the top insets visualizing splay–bend ribbons at the reconnection site before (left), during (middle) and after (right) the reconnection. The top insets show the details of structure change in the region of reconnections, based on the colour scheme shown in Fig. 2g. The knots in the bottom inset show the simplified knot topology before and after the reconnection (Supplementary Video 4). b, Knotted vortex length for repeated fusion and fission of trefoil vortices depicted in a. The purple and orange shades correspond to the length of separated trefoils and red triangles refer to the length of their connected sum. c, Switching between trefoil knots (purple and orange markers) and the multicomponent links (blue and cyan) shown in Fig. 2d–f, repeated multiple times (Supplementary Video 5). The red triangles refer to the intermediate graph structure facilitating the reconnection. d, Switching between a single trefoil knot (red) and three-linked loops (purple, orange and cyan). In b–d, the total knot length is plotted as the solid black curves; the dashed black lines are guides for the eye when the number of components changes. Top: applied voltage magnitude U of the pulse train. \({\tau }_{{\mathrm{a}}}\) (\({\tau }_{{\mathrm{o}}}\)) denotes the time interval between a switch in electric pulses and the corresponding link-changing fusion (fission) event. The parameters used are sample thickness d = 25 μm and pitch p = 5 μm.

Complex knots, graphs and analogues of high-baryon-number particles formed via fusion

Beyond single- and multicomponent knots and links, large composite structures formed via the fusion of many separate knots also exhibit topological features of graphs, which, in our case, are structures composed of edges in the form of vortex lines and vertices at their junctions (Fig. 6). Although three-dimensional spatial graphs are commonly seen as transient states separating the distinct knots before and after relinking (Figs. 2–5), for large structures formed via the fusion of many knots, they also emerge as energy-minimizing or metastable states (Fig. 6c–j and Supplementary Videos 6–10). The visualization of n(r) in the zoomed-in regions of complex inter-vortex’s junctions forming graphs confirms that the material director field remains non-singular within them (Fig. 6), as well as illustrates the details of branching, connections and reconnections of the vortex lines in the χ(r) field. Some of the components of complex vortex knots have multiple transformations between the local 1/2 and –1/2 structures along the closed loops, whereas the other components can maintain a single winding number, corresponding to 1/2 or –1/2 (Figs. 2c–g, 4 and 6c (insets) and Extended Data Fig. 6).

a,b, Two \(Q=2\) fused knot dimers shown in a, which previously formed through fusion of pairs of individual trefoil-shaped vortex knots (Extended Data Fig. 6), hybridize together to form a tetramer shown in b. The fusion was driven by switching voltage from ~3.7 V to ~4 V. Insets show simplified vortex knot schematics, where each closed loop is differently coloured. c, Graph state formed by reconnections within a vortex knot tetramer, with the circled four-valent node of vortex lines that can be resolved into different knot states depending on relinking; detailed configurations of vortex lines and the corresponding simplified knot schematics of the entire knots are illustrated in the boxed inset, where the top visualizations use the scheme shown in Fig. 2g and in the bottom ones, each closed-loop component is differently coloured. d–g, Two \(Q=3\) trimers shown in d, each obtained by fusing three elementary heliknotons, sequentially reconnect to produce a \(Q=6\) heliknoton (e), which evolves into transient (f) and then stable complex graph with several nodes (g) while conserving Q = 6; for dynamics, see Supplementary Video 6. The inset in d schematically shows distinctly coloured closed-loop vortex components prior to the reconnection depicted in e. The detailed configurations of vortex lines in the region of fusion are shown in the bottom insets of e–g according to the scheme also used in c. h,i, Eight \(Q=1\) heliknotons arranged closely together, as shown in h, fuse to form a vortex graph with \(Q=8\), in response to applying 4 V (h,i). j, A fused state of 18 elementary heliknotons relaxed from a perturbed lattice to form an interconnected graph with \(Q=18\) (Extended Data Fig. 8; Supplementary Video 7 shows the dynamics of the simulated POM); the complex knot is produced via the fusion of individual knots from an array by pulsing (three times) with voltage amplitudes between 1.5 V and 3 V. The simulated POMs of the knotted structures are shown as insets in h–j, which are obtained for crossed polarizers indicated by white double arrows. Parameters used in simulations are sample thickness d = 25 μm and pitch p = 5 μm; vortex cores are coloured by the n(r) orientation according to the scheme shown in Fig. 2e.

Although fusion and fission of two elementary heliknotons already has many diverse scenarios (Figs. 2–5), dependent on the relative directionality of the fusion of knots, even more possibilities arise for such processes involving more than two heliknotons (Fig. 6 and Extended Data Figs. 1–3). The pathways of the fusion of knots can be controlled by tuning the applied voltage and using laser tweezers, where the latter allows us to spatially translate heliknotons and to locally melt or realign the chiral LC in between the vortex knots, thereby prompting the desired reconnections to occur. Within the interior of a single heliknoton, the knotting topology can be controlled by changing the applied voltage. In the simplest case, the trefoil vortex state transforms into a three-component link by reducing the voltage (Fig. 4a). The corresponding reverse transformation can be induced by increasing the voltage. Proximity to other heliknotons can influence the interior knotting even in the absence of inter-heliknoton relinking, in some cases, producing the Solomon link (Fig. 4a) due to attractive heliknoton–heliknoton interactions. At first sight, the relation between the complex diverse knots and the concept of quasiatoms is elusive because the numbers of components (vortex loops and knots) as well as the numbers of crossings change during successive reconnections related to fusion and fission and other knot transformations. One would expect having integer invariants characterizing the quasiparticle knots that could represent the effective ‘baryon numbers’ or the effective number of nucleons. Despite the large spectrum of relinking possibilities and within the voltage range of stability of individual and fused knots, we find that the cumulative Hopf index of heliknotons, defined in the material field n(r), is conserved during fusion, fission and various other transformations. Indeed, characterizing the Hopf index as an integral, we find that the Hopf indices follow the addition of components during fusion and stay conserved as the number of elementary heliknotons taking part in interactions/transformations (Figs. 2–6 and Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5). For a solitonic unit vector field n(r) embedded in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) whose far-field background allows for compactification into \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{3}\), the Hopf index Q can be obtained as38,46

where \({F}_{\mathrm{ij}}={\epsilon }_{\mathrm{abc}}{n}^{{\mathrm{a}}}{\partial }_{\mathrm{i}}{n}^{\mathrm{b}}{\partial }_{\mathrm{j}}{n}^{\mathrm{c}}\), \(\epsilon\) is the Levi–Civita symbol and \({{\mathrm{A}}}_{\mathrm{i}}\) is defined as \({F}_{\mathrm{ij}}=\frac{1}{2}\left({\partial }_{\mathrm{i}}{{\mathrm{A}}}_{\mathrm{j}}-{\partial }_{\mathrm{j}}{{\mathrm{A}}}_{\mathrm{i}}\right)\); Einstein summation convention is used and details of the calculation are presented in the Methods. For all the studied transformations, the Hopf indices obtained via the integration of topological charge density before and after the relinking of vortices match (up to numerical errors) with the corresponding numerical integration values (Extended Data Fig. 5). These values of Hopf index are also consistent with the geometric analysis and interpretation of this topological invariant as the linking number between the preimages of any pair of distinct points on \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\), the order-parameter space of vectorized n(r) (Extended Data Fig. 4)46,47. Figure 6 and Extended Data Figs. 5, 6 and 8 show examples of different ‘isotopes’ that have the same Hopf index formed from the same initial heliknoton structures but with different vortex knotting and linking details. Interestingly, the fusion of elementary heliknotons helps to make complex analogues of high-baryon-number nucleons15 or high-atomic-number chemical elements, like in the original Kelvin’s vortex atom model and in topological Skyrme models of nucleons1,2,3,4.

Elasticity-mediated interactions and reconnections of vortex knots

The facile attractive interaction that leads to ‘double reconnections’ (Figs. 2 and 3) via the annihilation of vortex fragments with local opposite elementary winding numbers of ±1/2 can be understood as stemming from the attractive elasticity-mediated local interaction between the vortex regions of opposite winding numbers situated in the proximity of one another. This is both analogous and different from what was observed for vortices in water12, where the possibility of reconnections to occur depends on the directionality of swirling flows around the vortex cores. At the same time, other scenarios are possible, too, in which locally graph-like configurations can form as transient states, embedding a superposition of reconnected states that can take place (Figs. 5a and 6). Among other particularly interesting reconnection scenarios is the generation of a vortex loop that simultaneously reconnects multiple knots and serves as some kind of ‘glue’, fusing together the dischiralation vortex cores (Fig. 6e–g and Supplementary Video 6).

Since the Hopf index of our vortex-knot-containing structures is conserved before and after the reconnections that mediate the fusion and fission processes, one can ask: what is the minimum number of reconnections needed to go from one knot to another and keep Q constant? For all the studied knots that appear to have crossings of positive type both before and after the fusion/fission processes, a lower-bound estimate for it, and upper bound as well, can be obtained by calculating the reconnection numbers (or signature topological invariants) by following the recently introduced topological analysis of reconnections45. The relative reconnection number, determined as the difference \(\left|{R}(K_{\mathrm{i}})-{R}(K_{\mathrm{f}})\right|\) between the numbers of reconnections needed to unknot each of the knots, is indeed found to be the lower bound and, in some special instances, equals the number of reconnections that we observe (Extended Data Fig. 9). For example, the relative reconnection number for a single heliknoton undergoing internal reconnections is 2, consistent with what we observe. In a more complicated example involving two pairs of heliknotons consisting of three-linked rings (Fig. 4b (left) and Extended Data Fig. 9g), we again find the observed number of reconnections separating the two knots saturates the lower bound \(\left|{R}(K_{\mathrm{i}})-{R}(K_{\mathrm{f}})\right|=3\). Furthermore, since the application of special external stimuli such as very strong fields can destroy elementary heliknotons and lead to changes in Hopf index Q of fused composite knot soliton states, the multiplicity of vortex reconnections associated with such knot-destroying and Q-changing transformations also need to be considered, although they are outside the scope of this study.

It is also of interest to investigate what happens to the writhe during reconnections. Akin to what was found for the connected-sum type of formation of knotted DNA molecules42, we find that cumulative writhe is conserved during the elementary knot fusion/fission processes (Extended Data Fig. 9e). However, interestingly, this is not the case during internal intra-heliknoton reconnections nor more complex reconnections that go beyond the process of fusion and fission of elementary knots (Extended Data Fig. 9d).

Chirality and topology

Chirality of the LC host medium is essential for heliknoton stability as the chiral term in the free-energy functional allows for the (meta)stability of both helical background and heliknotons. Reversing the handedness of the host medium gives origin to the hopfions of opposite charge Q (refs. 33,34), which can be checked by consistently vectorizing the circulations of preimages47. The vortex knots, preimage links and host chiral LC medium are chiral, with the knot chirality preserved during elementary relinking operations within fusion and fission (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). In fact, all isotopes of vortex atoms can be thought of as obtained by relinking operations within the knots. Switching handedness of the host medium leads to energy-minimizing knots of opposite handedness, too. Although most known knots in mathematics are chiral and achiral knots are rather rare, one can ask whether achiral knots can be possibly obtained from the fusion of energetically stabilized elementary chiral knots. Although we did not obtain such achiral knots in experiments or numerical analyses so far, we identified a scenario in which specific series of band surgeries could lead to such achiral knots (Extended Data Fig. 10c), provided that both end and intermediate states are energy-minimizing structures under suitable material parameters and voltage-driving schemes, or in response to other external stimuli. Thus, our experimentally accessible system can be used to explore the interplay between chirality at hierarchically different levels, from that of chiral carbon centres of chiral dopant molecules within the LC to that of the chiral nematic host medium and to particle-like vortex knots embedded in it.

The topology of a chiral LC can be viewed from different perspectives33. On one hand, the order-parameter space for three-dimensional structures of non-polar n(r) is \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}/{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\), which can be smoothly vectorized for non-singular structures in three dimensions to yield an order-parameter space of \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\). From this viewpoint, the localized field configurations are simply hopfions classified by the third homotopy groups, \({\pi }_{3}\left({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}/{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\right)\) or \({\pi }_{3}\left({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\right)\), which are identified with the group of integers under addition, that is, \({\pi }_{3}\left({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}/{{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\right)={\pi }_{3}\left({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\right)={\mathbb{Z}}\). On the other hand, considering the mutually orthogonal χ(r) and n(r) fields together, the order-parameter space becomes the quotient space \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{3}/{Q}_{8}\) (refs. 10,48), where \({Q}_{8}\) is the quaternion group. In this framework, the vortex lines studied here can be considered as one of the elements of \({Q}_{8}\), since \({\pi }_{1}\left({{\mathbb{S}}}^{3}/{Q}_{8}\right)={Q}_{8}\), where unrestricted relinking is allowed because all the vortex lines belong to the same element of \({Q}_{8}\) (ref. 48). When on their own, knots of \({\pi }_{1}\left({{\mathbb{S}}}^{3}/{Q}_{8}\right)\) vortex lines would not necessarily have topological protection as they could be reduced to unknots, much like in the case of vortices in water12. However, the dual nature of our heliknotons manifests itself in the profound conservation of a topological invariant—the Hopf index—during all observed dischiralation vortex-relinking transformations.

The designs of artificial forms of matter and metamaterials with pre-engineered physical properties are in great demand to power the growth of modern technologies, but their atom-like building blocks are typically nanofabricated. The studied dischiralation vortex knots in chiral LCs exhibit particle-like meta-atom behaviour, with a striking resemblance of vortex knot models of atoms proposed by Kelvin1. Their promise for being the building blocks of metamatter stems from the fact that, much like conventional atoms or nucleons, they are characterized by integer-valued-Hopf-index topological invariants46,47,49, analogues of baryon and atomic numbers. The ability of on-demand reconnections within arrays and crystals of knots of various symmetries by applying electric fields locally using patterned electrodes, like in displays24, may allow for exploring the combinatorial diversity of complex knots and links that can be realized within a chiral LC medium. Being realized in the spatial structures of reconfigurable chiral LCs19,50, our knots may induce topologically non-trivial configurations in the phase or polarization of light with robust properties14,51. Therefore, heliknotons may find technological utility in electro-optics, singular optics and photonics. Furthermore, since similar topological objects and reconnection processes can be realized in chiral magnets11, the stability, fusion and fission of knots could be potentially used in spintronics, data storage and unconventional computation.

Methods

Materials and sample preparation

The chiral LC mixture used was prepared from 4-cyano-4′-pentylbiphenyl (5CB, EM Chemicals), doped with the left-handed chiral additive cholesterol pelargonate (Sigma-Aldrich). To obtain a target pitch of p = 5–10 μm for the mixture, the formula \({c}_{{\rm{d}}}=(\text{HTP})^{-1}p^{-1}\) where \({c}_{{\mathrm{d}}}\) is the mass concentration of the chiral additive and HTP = 6.25 μm−1 refers to the helical twisting power for cholesterol pelargonate in 5CB. The resulting pitch of chiral LCs was confirmed using the Grandjean–Cano wedge cell method10. For samples prepared to conduct nonlinear imaging, 80% of the chiral 5CB mixture was mixed with 19% of reactive mesogen RM-257 (Merck) and 1% photoinitiator Irgacure 369 (Sigma-Aldrich). To prepare LC cells responsive to electric fields, indium-tin-oxide-coated glass substrates were spin coated with PI-2555 (HD MicroSystems) at 2,700 rpm for 30 s and subsequently baked for 5 min at 90 °C, followed by an hour at 180 °C. The polyimide-coated side was rubbed with a velvet cloth to produce a preferred planar alignment for LC molecules. The as-prepared indium-tin-oxide-coated glass substrates were then assembled into LC cells using ultraviolet-curable glue with silica spheres whose diameters range from 20 µm to 30 μm inserted between the substrates to provide a well-defined cell gap. The indium-tin-oxide-coated glass was then soldered with copper wires and attached to a voltage supply (GFG-8216-A, GW Instek) to control the voltage across the cell. The assembled cells were filled with chiral LC mixtures through capillary forces.

Generating and imaging localized heliknotons in chiral LCs

All the experiments were performed at room temperature. The generation of heliknotons was carried out by holographic laser tweezers focusing a 10–30-mW laser beam produced by an ytterbium-doped continuous-wave fibre laser (YLR-10-1064, IPG Photonics) into the cell, when a voltage of ~2–3 V at 1 kHz was applied across the sample. The holographic laser tweezers setup can produce arbitrary patterns of laser intensity within the sample, though a focused beam that locally disrupts the orientational order of the LC material is generally sufficient to create initial conditions for the system that relax into heliknotons when a suitable voltage is applied. The beam only needs to be applied for a few seconds to initialize a heliknoton. Once generated, a laser power of ~5 mW can be utilized to steer heliknotons and guide their interaction and assembly, thereby forming lattices, arrays and hybridized vortex knots and simultaneously adjusted by the applied voltage. The pairwise interaction between heliknotons can be modulated by increasing or reducing the voltage, initiating vortex reconnection events dependent on the positions and orientations of the heliknotons involved. POM images were taken with an IX-81 Olympus microscope incorporated with the holographic laser tweezers mentioned above, using a pair of orthogonally orientated polarizers, to allow for in situ imaging by a charge-coupled device camera (Flea FMVU-13S2C-CS, Point Grey Research). Several high-numerical-aperture objectives ranging from ×100, ×40 and ×20 magnifications (numerical aperture of 1.4, 0.75 and 0.4, respectively) were used in experiments to observe detailed structures of individual heliknotons or assemblies and crystals of multiple heliknotons with a larger field of view.

Three-dimensional nonlinear optical imaging

To resolve the detailed structure within heliknotons and fused heliknoton structures, we utilized a three-photon emission fluorescence polarizing microscopy setup, which is directly integrated with the IX-81 microscope described above. To prepare samples for three-photon emission fluorescence polarizing microscopy, after generating soliton structures in a cell with the polymerizable chiral LC mixture, ultraviolet light from a 20-W mercury lamp was concentrated onto a small region of interest through an aluminium foil mask with a pinhole to locally polymerize and preserve the orientational order by crosslinking the reactive mesogens. The small polymerization region allows heliknotons to be generated and ‘frozen’ at multiple spots within a cell sequentially, improving the throughput. Once polymerized, the cell was split apart and most of the unpolymerized 5CB molecules were washed away with isopropyl alcohol and replaced with index-matching immersion oil. This procedure was done to minimize birefringence of the LC material, which can lead to imaging artifacts, and maintain the LC \({\bf{n}}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\) configurations. A Ti-sapphire oscillator (Chameleon Ultra II, Coherent) operating at 870 nm with 140-fs pulses at 80-MHz repetition rate was used to excite the remaining 5CB molecules by three-photon absorption. The fluorescence signal is filtered with a 417/60-nm bandpass filter and detected in the forward-detection mode using a photomultiplier tube (H5784-20, Hamamatsu). The signal intensity of the three-photon absorption process scales with \({\cos }^{6}\left(\beta \right)\), where β is the relative angle between the long axis of the 5CB molecule and the polarization vector of light. For imaging scans done in this work, circularly polarized light, obtained by a quarter-wave plate, was utilized to extract the preimages of \({\bf{n}}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\) aligned along the far-field helical axis χ0, corresponding to regions with the lowest fluorescence signal. Isosurfaces extracted from experimental imaging were then analysed and contrasted with the corresponding numerical structure relaxed from initial conditions matching the experimental starting configuration.

Numerical modelling of heliknotons via energy minimization

Numerical modelling of fusion and fission of heliknotons and other knotted solitonic structures is based on minimizing the Frank–Oseen free-energy functional:

via the finite-difference method. Here \({F}_{\text{elastic}}\) accounts for elastic energy penalties incurred due to splay (\({k}_{11}\)), twist (\({k}_{22}\)), bend (\({k}_{33}\)) and saddle-splay (\({k}_{24}\)) deformations and takes the form

The saddle-splay energy contributes to the energetics of defects and surface-anchoring energy53,54. Since the n(r) configurations considered in this work are continuous and strong anchoring conditions are applied, we set \({k}_{24}\) to zero. The other elastic constants \({k}_{11}\) (6.4 pN), \({k}_{22}\) (3.0 pN) and \({k}_{33}\) (10.0 pN) take the experimentally determined values of 5CB. Similarly, the electric contribution is defined by

where \({\bf{E}}\) is the applied field, \({\varepsilon }_{0}=8.854\times {10}^{-12}\,\text{F}\,{\text{m}}^{-1}\) is the permittivity of vacuum, \({\varepsilon }_{\perp }\) is the dielectric coefficient perpendicular to the director axis and \(\Delta \varepsilon\) is the dielectric anisotropy of the LC medium. For 5CB, \(\Delta \varepsilon\) and \({\varepsilon }_{\perp }\) take the values of 13.8 and 5.2, respectively. The equations of motion for the director field were obtained by varying the total energy functional and replacing the derivatives with their fourth-order finite-difference counterparts. This, subsequently, yields a set of coupled algebraic equations at each grid point to locally update the director field. To ensure numerical stability, an under-relaxation routine was performed such that the successive numerical solution is a weighted average of the old and new solutions: \({n}_{\mathrm{i}}\to \alpha {n}_{\mathrm{i}}+\left(1-\alpha \right){n}_{\mathrm{i}}^{{\prime} }\). The parameter \(\alpha \in \left[\mathrm{0,1}\right]\) is generally set to \(\alpha =0.1\) and was chosen empirically to ensure a convergent solution. To account for local distortions in the electric field due to the dielectric nature of the LC material, after each subsequent update for the director field, the voltage is updated by minimizing the free energy with respect to the electric field and substituting the derivatives of voltage with fourth-order finite-difference derivatives. This yields an equation to update the electric field at each grid point evolving the voltage simultaneously as the director field is relaxed. Periodic boundaries were assigned to the planes perpendicular to the helical axis, whereas hard boundary conditions were defined on the top and bottom of the cell. High-throughput grid calculations were performed in parallel via code written in C++ with CUDA acceleration.

Heliknotons are initialized from the ansatz6,9,17

where \({\vec{{\bf{N}}}}_{{\mathrm{bg}}}\left(\vec{{\bf{r}}}\right)=\cos \left(2{{\pi}}z/p\right)\hat{{\bf{x}}}+\sin \left(2{\pi}z/p\right)\hat{{\bf{y}}}\) defines the background helical director field, \(p\) is the pitch and \({\bf{q}}\left({\bf{r}}\right)=\cos \left({\pi}{Qr}/p\right)+\sin \left({\pi}{Qr}/p\right)\hat{{\bf{r}}}\) is a quaternion. Here Q is an integer that defines the charge of the heliknoton and is set to unity for elementary heliknotons. In our modelling, to obtain the final heliknoton ansatz \({\bf{n}}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\), the z component of \({\bf{n}}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\) is inverted:

For initial conditions involving multiple elementary heliknotons, a cut-off radius is chosen to be the pitch \(p\) to allow for the embedding of multiple heliknotons in a uniform helical background. This is carried out by superimposing the ansatz configurations for heliknotons localized at different locations \(\{{{\bf{r}}}_{\mathrm{i}}\}\). The ansatz above is then relaxed according to the energy-minimizing procedure described above.

To calibrate the elapsed time in simulations to match that of the experiments, we reconstruct the same initial conditions for both experiment and numerical simulations of the reconnection corresponding to Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 6. For a node density of 253p−3, we find the time elapsed for each iteration to be 0.205 ms.

Fusion and fission response times

We explore the dynamic characteristics of elementary heliknotons fusing and splitting apart by pulsing the applied voltage. Here we describe the dependence of the response times \({\tau }_{{\mathrm{a}}}\) (\({\tau }_{{\mathrm{o}}}\)) as a function of the voltage amplitude in detail. Although a complete characterization of the switching dynamics is beyond the scope of this work, the most relevant parameter allowing one to tune the switching dynamics is the applied voltage magnitude (Extended Data Fig. 7). Given a pair of heliknotons in the trefoil state just before (after) a fusion event, the response time \({\tau }_{{\mathrm{a}}}\) (\({\tau }_{{\mathrm{o}}}\)) diverges for a critical voltage dependent on the separation distance and the relative orientation of the heliknoton–heliknoton pair. This critical voltage can be interpreted as the voltage that typically stabilizes a four-valent intermediate graph topology instead of completing the reconnection event. As the applied voltage deviates from the critical voltage, the response times sharply drop and saturate to finite subsecond values. Note that the response times in Extended Data Fig. 7 are somewhat smaller than those observed in Fig. 5b,c due to the closer distance at which the heliknotons were initialized in this context. The set of parameters used above can be translated to other experimental geometries by noting the Frank–Oseen free-energy functional can be rescaled by the pitch without influencing the equations of motion. Thus, the response time (neglecting initial conditions) appears to depend only on the dimensionless electric field defined by \(\widetilde{{\mathrm{E}}}=\sqrt{{\varepsilon }_{0}\Delta \varepsilon /\bar{K}}\left(V/\widetilde{{\mathrm{d}}}\right)\), where \(\widetilde{{\mathrm{d}}}\) is the thickness of the cell expressed in units of pitch \(p\) and \(\bar{K}\) is the average elastic constant at room temperature.

Visualization and topological characterization of heliknotons

The helical axis field \({\bf{\chi }}({\bf{r}})\) is obtained by constructing the chirality tensor \({C}_{\mathrm{ij}}={\partial }_{\mathrm{i}}{n}_{l}{\epsilon }_{\mathrm{jlk}}{n}_{\mathrm{k}}\), where Einstein summation convention is assumed and obtaining the dominant principal eigenvector, which defines the orientation of the local non-polar helical axis \({\bf{\chi }}({\bf{r}})\). Local regions within heliknotons that do not have a well-defined chiral axis correspond to vortex lines. In this work, we colour these vortex lines according to their local director orientation on the \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\) sphere. Vortex knots obtained by sampling the raw grid points are often coarse. To improve the quality of these knots, vortices are first smoothed via Taubin smoothing to ensure a faithful reconstruction of the knot topologies55. These smoothed isosurface data are then used to construct a graph, which is traversed to find link components before and after knot reconnections. When graphs can be successfully resolved into links, the corresponding knot diagrams are imported into the KnotPlot freeware52 for three-dimensional visualization, after which they can further analysed. Ribbons of splay–bend in a tubular neighbourhood about the vortex lines are produced by constructing a tensor \({\mathbb{Q}}\left({\bf{\chi }}\right)={\bf{\chi }}\otimes {\bf{\chi }}-1/3\) and calculating the splay–bend parameter \({S}_{\text{SB}}={\partial }_{\mathrm{i}}{\partial }_{\mathrm{j}}{{\mathbb{Q}}}_{\mathrm{ij}}\) (here Einstein summation is assumed)56. The blue and yellow ribbons indicate regions with \({S}_{\text{SB}} > 0\) and \({S}_{\text{SB}} < 0\), respectively, and correspond to isosurfaces of \({S}_{\text{SB}}\) values of 10% of the average positive splay–bend \(\left\langle {S}_{\text{SB}}^{+}\right\rangle\) and 10% of the average negative splay–bend \(\left\langle {S}_{\text{SB}}^{-}\right\rangle\) within the tubular neighbourhood of the vortex knot. To produce smooth ribbons close to the vortex cores in which \({\boldsymbol{\chi }}\) is ill-defined, \({S}_{\text{SB}}\) at each grid point is locally averaged with its nearest neighbours.

Hopf indices of elementary and hybridized heliknotons are numerically computed according to the following procedure described elsewhere38,46. First, we make the identification \({b}^{\mathrm{i}}={\epsilon }^{\mathrm{ijk}}{F}_{\mathrm{jk}}={\epsilon }^{\mathrm{ijk}}{\partial }_{\mathrm{j}}{{\mathrm{A}}}_{\mathrm{k}}\), allowing us to associate the quantity \({\bf{A}}\) with a vector potential of \({\bf{b}}={\pmb{\nabla }}{\bf{\times }}{\bf{A}}\). The Hopf index Q can then be written as \(Q=\frac{1}{64{{\mathrm{\pi }}}^{2}}\int {{\mathrm{d}}}^{3}{\bf{r}}({\bf{b}}\cdot {\bf{A}})\). It follows that on computing \({\boldsymbol{b}}\), the vector potential \({\bf{A}}\) is obtained from numerical integration and Q can be obtained. All numerical derivatives are performed with fourth-order accuracy, yielding Hopf indices that agree within numerical error with the number of heliknotons initialized. The Hopf charge may also be determined by counting the linking number of different vectorized preimages47. The north- and south-pole preimages correspond to the director orientations along χ0 or the z axis. These preimages can be numerically extracted by computing isosurfaces according to the condition \(\left|{\bf{n}}\left({\bf{r}}\right)-{{\bf{n}}}_{\mathrm{t}}\right| < \eta\), where \(\eta\) is a numerical tolerance set to 0.1 corresponding to a small neighbourhood of allowed vectorized \({\bf{n}}\left({\bf{r}}\right)\) orientations surrounding the target orientation \({{\bf{n}}}_{\mathrm{t}}\).

Simulated POM movies were generated by applying a simple Jones matrix approach. We begin with a homogeneous input vector \({{\bf{E}}}_{0}={\left(\begin{array}{cc}1 & 0\end{array}\right)}^{{\mathrm{T}}}\) representing linearly polarized light along the x axis of a given wavelength λ. Rays of light are assumed to propagate along the far-field helical axis χ0 (along the z axis) of the cell followed by a crossed polarizer aligned with the y axis. For a small LC volume of thickness \(\Delta z\) with the director aligned with the x axis, the corresponding Jones matrix is

where \({\delta }_{0}=2{\pi}{n}_{\mathrm{o}}\Delta z/\lambda\) and \({\delta }_{\mathrm{eff}}=2{\pi}{n}_{\mathrm{eff}}\Delta z/\lambda\) are the phases of the fast and slow axes, respectively. The extraordinary (\({n}_{{\mathrm{e}}}\)) and ordinary (\({n}_{{\mathrm{o}}}\)) refractive indices are related to the effective refractive index accounting for the out-of-plane angle \(\theta\) of the director and is given by

In a medium of 5CB, \({n}_{{\mathrm{e}}}\) and \({n}_{{\mathrm{o}}}\) assume the values of 1.77 and 1.58, respectively. More generally, for directors with an angle \(\phi\) from the x axis in the x–y plane, a rotation \(R\left(\phi \right)\in \mathrm{SO}\left(2\right)\) can be applied to \({J}_{0}\) according to \(J\left({\theta},{\phi}\right)=R\left(\phi \right){J}_{0}\left({\theta }\right)R{\left(\phi \right)}^{{\mathrm{T}}}\). Applying this Jones matrix ansatz to the discretized grid geometry above, the effective Jones matrix for each point (x, y) in the focal plane is obtained by multiplying successive Jones matrices from different layers together corresponding to a column with \({N}_{\mathrm{z}}\) elements along the helical axis:

The output polarization for a given wavelength is obtained by applying \(M\left(x,y\right)\) to the input polarization and selecting the second component \({{\mathrm{e}}}_{\mathrm{y}}^{\left({\lambda }\right)}\) due to the output polarizer. The normalized intensity is computed from the squared magnitude of the output. This procedure is carried out for 650-, 550- and 450-nm light, with relative intensities of 1.0, 0.6 and 0.3, respectively, determined by the spectral content of the light source used in the experiments. For still POMs, the open-source software Nemaktis57 with the ability to model more complex optical effects via ray-tracing and beam propagation (Extended Data Fig. 4b, bottom) was found yielding images generally consistent with the ones modelled by the Jones matrix approach. We found that both our Jones matrix approach and Nemaktis yield results that agree well with the experiments.

Tracking interactions between heliknotons via POM imaging

To track the separation vector between two heliknotons during fusion and fission using POM, we make use of their key property: heliknotons have orientations and positions along the far-field helical axis coupled, thereby undergoing a screw-like rotational motion when translated along the far-field helical axis10. In the POM video (Supplementary Video 2), by recording the change in a relative angle describing the heliknoton’s azimuthal orientation, the heliknoton’s dynamics across the sample thickness (along the z axis and far-field helical axis) can be tracked, in addition to tracking its lateral displacement. It follows that by defining \(\psi\) to be the relative angle between the long axes of the two heliknotons, one obtains \(\psi =2{\pi}{s}_{\mathrm{z}}/p\), where \({s}_{\mathrm{z}}\) is their separation in z. Since the in-plane heliknoton separation can be directly determined from the POM images, the full separation vector between the two heliknotons can be reconstructed. The same procedure can be applied to simulated POM images of numerically simulated heliknotons as well, to enable a direct comparison of fusion/fission between experiments and simulations. In experimental cells that are less than \(4p\) in thickness, heliknotons tend to persist in the midplane of the cell, allowing \(\psi\) to be easily determined as the heliknotons are perturbed from equilibrium by changing the voltage or laser tweezers manipulation.

Characterization of knot topology

A crucial aspect of our findings is the translation of our vortex knots, and the simplified diagrams introduced to faithfully represent their topologies and site-specific reconnections. We choose to represent these reconnections in diagrams via blue and green bands corresponding to band surgeries associated with internal and external heliknoton reconnections, respectively (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 9d–g). Additionally, information about the local winding number of the vortices is also important as reconnections often occur through a reconnection mechanism involving the annihilation (fusion) or pair creation (fission) between the vortex segments of opposite winding number. We find that for all links obtained, all reconnections analysed can be identified with the mathematical operation of coherent band surgery in which orientations are preserved3,45. From the diagrams produced, one can track the evolution of the writhe as vortex knots and links undergo reconnections3,42,43,44,45. The writhe serves as a simple measure of complexity in the knots we obtain as they are generated from right-handed trefoil building blocks in which the action of incorporating another trefoil into a complex composite knot only increases the writhe (Extended Data Fig. 9).

Like the writhe, one can compute the so-called reconnection number for a given knot or link. The reconnection number of a knot or link is the least number of reconnections that need to be performed to transform it to an unknot43,45. In general, this number is not known, but computable bounds on it from below exist (such as the so-called signature of the knot) and a very particular upper bound is always known that we shall call the R-number of the knot or link and denote by R(K), where K is the link. In this case, one simply smooths crossings such that the local knot orientation is preserved (Extended Data Fig. 9a)45. The circles generated by this action are called Seifert circles3,45. The R-number is defined as45

where \(c\) is the number of crossings in the original diagram and \(s\) is the number of Seifert circles. The meaning of the formula is that one can perform reconnections at \(R\) crossings (it is lower than the total number of crossings) and obtain an unknot45. This is shown in Extended Data Fig. 9b for the trefoil knot and implicitly for other examples in the figure. Once one has the reconnection numbers for a reconnection pathway (\(K_{\mathrm{i}}\to K_{\mathrm{f}}\)), it follows that the relative R-number \(\left|{R}(K_{\mathrm{i}})-{R}(K_{\mathrm{f}})\right|\) is a well-defined quantity that estimates from above the minimal number of reconnections necessary to transform \(K_{\mathrm{i}}\) to \(K_{\mathrm{f}}\). If the link K has all positive crossings (Extended Data Fig. 9), then R(K) is equal to the reconnection number of K. In general, for any K, the link or knot K can be transformed into an unknot in R(K) reconnections. R(K) is the least among all the possible unknottings when K is positive.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the article and its Supplementary Information. Data are also available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used for the numerical calculations are provided in the Supplementary Information.

References

Thomson, W. 4. On vortex atoms. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. 6, 94–105 (1869).

Turner, J. C. & van de Griend, P. History and Science of Knots (World Scientific, 1996).

Kauffman, L. H. Knots and Physics Vol. 1 (World Scientific, 2001).

Smalyukh, I. I. Review: knots and other new topological effects in liquid crystals and colloids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 83, 106601 (2020).

Faddeev, L. & Niemi, A. J. Stable knot-like structures in classical field theory. Nature 387, 58–61 (1997).

Manton, N. & Sutcliffe, P. Topological Solitons (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004).

Sutcliffe, P. Skyrmion knots in frustrated magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 247203 (2017).

Dennis, M. et al. Isolated optical vortex knots. Nat. Phys. 6, 118–121 (2010).

Han, J. H. Skyrmions in Condensed Matter (Springer, 2017).

Tai, J.-S. B. & Smalyukh, I. I. Three-dimensional crystals of adaptive knots. Science 365, 1449–1453 (2019).

Voinescu, R., Tai, J.-S. B. & Smalyukh, I. I. Hopf solitons in helical and conical backgrounds of chiral magnetic solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 057201 (2020).

Kleckner, D. & Irvine, W. Creation and dynamics of knotted vortices. Nat. Phys. 9, 253–258 (2013).

Wang, K., Dutt, A., Wojcik, C. C. & Fan, S. Topological complex-energy braiding of non-Hermitian bands. Nature 598, 59–64 (2021).

Sugic, D. et al. Particle-like topologies in light. Nat. Commun. 12, 6785 (2021).

Naya, C. & Sutcliffe, P. Skyrmions and clustering in light nuclei. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 232002 (2018).

Lin, W., Mata-Cervera, N., Ota, Y., Shen, Y. & Iwamoto, S. Space-time optical hopfion crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 083801 (2025).

Shnir, Y. M. Topological and Non-Topological Solitons in Scalar Field Theories (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Chaikin, P. M. & Lubensky, T. C. Principles of Condensed Matter Physics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995).

Meng, C., Wu, J.-S. & Smalyukh, I. I. Topological steering of light by nematic vortices and analogy to cosmic strings. Nat. Mater. 22, 64–72 (2023).

Gennes, P.-G. & de Prost, J. The Physics of Liquid Crystals (Clarendon Press, 2013).

Kim, D. S., Lee, Y.-J., Kim, Y. B., Wang, Y. & Yang, S. Autonomous, untethered gait-like synchronization of lobed loops made from liquid crystal elastomer fibers via spontaneous snap-through. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh5107 (2023).

Khoo, I.-C. & Wu, S.-T. Optics and Nonlinear Optics of Liquid Crystals (World Scientific, 1993).

White, T. J. & Broer, D. J. Programmable and adaptive mechanics with liquid crystal polymer networks and elastomers. Nat. Mater. 14, 1087–1098 (2015).

Yeh, A. P. & Gu, C. Optics of Liquid Crystal Displays (Wiley, 2010).

Lyu, P., Broer, D. J. & Liu, D. Advancing interactive systems with liquid crystal network-based adaptive electronics. Nat. Commun. 15, 4191 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. Shape morphing directed by spatially encoded, dually responsive liquid crystalline elastomer micro-actuators. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208613 (2023).

Sultanov, V. et al. Tunable entangled photon-pair generation in a liquid crystal. Nature 631, 294–299 (2024).

Kos, Ž & Dunkel, J. Nematic bits and universal logic gates. Sci. Adv. 8, eabp8371 (2022).

Wang, X., Miller, D. S., Bukusoglu, E., De Pablo, J. J. & Abbott, N. L. Topological defects in liquid crystals as templates for molecular self-assembly. Nat. Mater. 15, 106–112 (2016).

Martinez, A. et al. Mutually tangled colloidal knots and induced defect loops in nematic fields. Nat. Mater. 13, 258–263 (2014).

Bowick, M. J., Chandar, L., Schiff, E. A. & Srivastava, A. M. The cosmological Kibble mechanism in the laboratory: string formation in liquid crystals. Science 263, 943–945 (1994).

Tkalec, U., Ravnik, M., Čopar, S., Žumer, S. & Muševič, I. Reconfigurable knots and links in chiral nematic colloids. Science 333, 62–65 (2011).

Ackerman, P. J. & Smalyukh, I. I. Diversity of knot solitons in liquid crystals manifested by linking of preimages in torons and hopfions. Phys. Rev. X 7, 011006 (2017).

Ackerman, P. J. & Smalyukh, I. I. Static three-dimensional topological solitons in fluid chiral ferromagnets and colloids. Nat. Mater. 16, 426–432 (2017).

Machon, T. & Alexander, G. P. Knots and nonorientable surfaces in chiral nematics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14174–14179 (2013).

Jampani, V. S. R. et al. Colloidal entanglement in highly twisted chiral nematic colloids: twisted loops, Hopf links, and trefoil knots. Phys. Rev. E 84, 031703 (2011).

Zhang, Q., Ackerman, P. J., Liu, Q. & Smalyukh, I. I. Ferromagnetic switching of knotted vector fields in liquid crystal colloids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 097802 (2015).

Tai, J.-S. B., Ackerman, P. J. & Smalyukh, I. I. Topological transformations of Hopf solitons in chiral ferromagnets and liquid crystals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 921–926 (2018).

Machon, T. & Alexander, G. P. Knotted defects in nematic liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 027801 (2014).

Pachos, J. K. Introduction to Topological Quantum Computation (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

Teng, H., Zhong, J., Chen, J., Lei, X. & Zhan, Q. Physical conversion and superposition of optical skyrmion topologies. Photon. Res. 11, 2042 (2023).

Katritch, V., Olson, W. K., Pieranski, P., Dubochet, J. & Stasiak, A. Properties of ideal composite knots. Nature 388, 148–151 (1997).

Kleckner, D., Kauffman, L. & Irvine, W. How superfluid vortex knots untie. Nat. Phys. 12, 650–655 (2016).

Milnor, J. W. Topology from the Differentiable Viewpoint (Princeton Univ. Press, 1997).

Kauffman, L. H. Topology of vortex reconnection. in Inverse Problems: In Memory of Professor Zbibniew Oziewicz Vol. 824 (eds Makaruk, H. E. & Owczarek, R. M.) 47–66 (American Mathematical Society, 2025).

Whitehead, J. H. C. An expression of Hopf’s invariant as an integral. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 33, 117–123 (1947).

Bott, R., Tu, L. W. Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology (Springer-Verlag, 1995).

Wu, J.-S., Valenzuela, R. A., Bowick, M. J. & Smalyukh, I. I. Topological rigidity and non-Abelian defect junctions in chiral nematic systems with effective biaxial symmetry. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021036 (2025).

Hopf, H. Über die Abbildungen der dreidimensionalen Sphäre auf die Kugelfläche. Math. Ann. 104, 637–665 (1931).

Born, M. et al. Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1999).

Guo, H. et al. Self-healing of optical skyrmionic beams. J. Opt. 27, 025604 (2025).

Scharein, R. G. & Rawdon, E. J. in Knotted Fields (eds Ricca, R. L. & Liu, X.) 281–317 (Springer Nature, 2024).

Selinger, J. V. Interpretation of saddle-splay and the Oseen-Frank free energy in liquid crystals. Liq. Cryst. Rev. 6, 129–142 (2018).

Tai, J.-S. B. & Smalyukh, I. I. Surface anchoring as a control parameter for stabilizing torons, skyrmions, twisted walls, fingers, and their hybrids in chiral nematics. Phys. Rev. E 101, 042702 (2020).

Taubin, G. Curve and surface smoothing without shrinkage. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 852–857 (IEEE, 1995).

Žumer, S., Čančula, M., Čopar, S. & Ravnik, M. Imaging and visualization of complex nematic fields. In Proc. SPIE Liquid Crystals XVIII 91820C (SPIE, 2014).

Poy, G. & Žumer, S. Ray-based optical visualisation of complex birefringent structures including energy transport. Soft Matter 15, 3659–3670 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Lee and H. Zhao for discussions and technical assistance. This research was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, under contract number DE-SC0019293 with the University of Colorado at Boulder. I.I.S. and L.H.K. acknowledge the hospitality of the International Institute for Sustainability with Knotted Chiral Meta Matter (WPI-SKCM2) during their sabbatical visits. We are grateful to R. Scharein and acknowledge the use of the KnotPlot freeware52 medium (https://knotplot.com) in creating some of the simplified diagrammatic visualizations corresponding to their experimental and computational results (coloured insets of knots and links are shown in Figs. 3f and 4).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.H. and J.-S.B.T. performed the experiments and numerical modelling, under the supervision of I.I.S. D.H., L.H.K., J.-S.B.T. and I.I.S. analysed the topological invariants of knots. I.I.S. conceived and directed the research. D.H., J.-S.B.T. and I.I.S. wrote the paper, with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Inge Nys and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 POM micrographs of laser-tweezer-driven vortex reconnections.

a, Two elementary heliknotons spontaneously fusing into a dimer; here sample thickness d = 30 μm, pitch p = 5 μm, and voltage U = 3.4 V. b, c, Laser tweezer manipulation of heliknotons to construct more complex vortex knots by incrementally fusing elementary ones greater complexity (b) and obtaining a “tangle” of fused heliknotons (c). Crossed polarizer orientations are indicated by white double arrows. The relevant parameters are d = 15 μm, p = 4.5 μm, and U = 2.1 V in b and d = 17.5 μm, p = 5.4 μm, and U = 1.8 V in c.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Fusion of complex knots from a lattice of elementary heliknotons.

a–c, Time evolution of several heliknoton lattices perturbed from equilibrium by increasing the applied voltage. Black double arrows indicate crossed polarizer orientations. In (b), sample thickness d = 17.5 μm, pitch p = 5.4 μm, and applied voltage U = 1.8 V in the first frame and 2.3 V in subsequent frames. In (a) and (c), d = 16 μm, p = 6.9 μm, and U = 1.7 V in the first frame and 2.1 V in subsequent frames. The real-time dynamics of transformations corresponding to a and c is shown in SI Video 8.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Laser-tweezer-guided fusion of chains and clusters of heliknotons.

a, Various fused heliknoton assembly guided by laser tweezers. b, c, In-situ optical manipulation of heliknoton chains fusing with heliknoton dimers at different controlled contact sites. The corresponding real-time dynamics is shown in SI Video 9. Black arrows show crossed polarizer orientations. In (a–c), sample thickness d = 16 μm, pitch p = 6.9 μm, and voltage U = 1.7 V.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Structure of fused heliknotons reconstructed numerically and experimentally.

a, Simulated midplane cross-sections of a fused heliknoton colored according to director orientations corresponding to the \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\) sphere in the right column. Parameters used: sample thickness 20 μm, pitch 5 μm, applied voltage 2.8 V. White and black loops visualize the north- and south-pole preimages (with director orientations colinear to cell normal \(\hat{z}\)) of the director field, respectively. b, Experimental (top) and numerical (bottom) POM images of the fused heliknotons shown in a. White arrows indicate crossed polarizer orientations. c, Reconstructed experimental (top) and numerical (bottom) nonlinear fluorescence images obtained using circularly polarized laser excitation. Dark regions correspond to north- and south-pole preimages while bright regions are coplanar with director orientations confined to the cross-sectional plane. d, North- and south-pole preimages extracted from experimental 3PEF-PM imaging (top) and corresponding numerical simulations (bottom). Preimages are colored according to the \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\) -based scheme shown in a.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Zoo of knots with different Hopf indices obtained via knot fusion.

Integers at the top-left of each row are the expected Hopf index values and numbers above each structure are the corresponding numerically computed Hopf indices. Cores of vortex knots are colored by their director orientation on the \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\) sphere defined in Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 4a. SI Video 10 shows dynamics of fusion of heliknotons with the net total Hopf index of \(Q=3\) and \(Q=4\). Bottom-right insets are the simplified multi-component links generated by KnotPlot software. Dots between structures with Hopf index 8 and 18 imply the vast variety of knots that exist between the two structures but have not been shown in this figure.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Vortex reconnections during fusion of two heliknotons.

a–e, Vortex fusion of two separate heliknotons into a three-component link visualized with colored vortex knots (according to the scheme in Fig. 2e) and ribbons of splay and bend colored according to the scheme in Fig. 2g. The time arrow indicates the temporal progression of evolution of the two trefoils in a into the link seen in e. The parameters used are: sample thickness d = 25 μm, pitch p = 5 μm, and voltage U = 3.9 V.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Reconnection switching response times.

a, Response times \({\tau }_{{\mathrm{a}}}\) (\({\tau}_{{\mathrm{o}}}\)) for two heliknotons reconnecting (separating) along the far-field helical axis χ0 (as shown in Fig. 5a, b) and b, two heliknotons reconnecting while approaching each other at 45 degrees with respect to χ0 (corresponding to Figs. 2d, f and 5c). Simulations were performed for a cell of thickness 25 μm and chiral LC pitch 5 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Numerically simulated heliknoton lattice hybridization for Q = 18.

a–e, Evolution of a heliknoton lattice (a) once prompted to evolve from an initial configuration into a knotted graph (e) by pulsing with voltages between 1.5-3 V (b–e) in a cell with thickness 50 μm and pitch 10 μm. Top row shows the POM micrographs of the lattice and the bottom row shows the corresponding vortex knots colored by director orientations in the vortex cores according to the scheme in Fig. 2e. Crossed white double arrows denote the crossed polarizer orientation used to compute the POM micrographs. The simulation was performed in the one-constant (obtained as an average of Frank elastic constants) approximation to reduce computation time.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Writhe and reconnection numbers for knot transformations.

a, A reconnection event between two vortices (top). A reconnection event (\(r\)) at a crossing results in a smoothed crossing (bottom). b, Reconnection of a trefoil knot. Dashed lines in (a, b) denote reconnection sites. c, Calculations for writhe \(w\) (top) and reconnection number \(R\) (bottom) for a trefoil knot. On the top, red and blue arrows denote the sign of a crossing as +1 and −1, respectively. Gray (black) lines on the trefoil refer to +1/2 (-1/2) winding number vortex segments, as defined in Fig. 2c. On the bottom, red arrows serve as guides to the eye to track the local orientation of the trefoil knot. Here \(c\) refers to the number of crossings (marked with red dashes) and \(s\) to the number of Seifert circles (black loops) obtained after smoothing the crossings. d, e, Writhe \(w\) and reconnection numbers \(R\) before and after reconnection for a single trefoil (c) and two trefoil knots (e). Large black arrows in d, e with band diagram schematics (see Figs. 4 and 5) relate the initial link (Ki) to the final link (Kf). The blue shaded box highlights the region where reconnections occured. f, g, Oriented knot diagrams and their corresponding Seifert circle diagrams used to compute the writhe and reconnection numbers for each knot denoted as K. e–g, Red arrows marking crossings indicate a positive contribution to the writhe. Top-right insets show simplified KnotPlot schematics for the knots obtained. Blue and green lines (d–g) in the upper panels denote intra- and inter-heliknoton reconnections, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Left- and right-handed vortex knots.

a, b, Left and right-handed knot diagrams and their KnotPlot representations summarize results for a left-handed and a right-handed chiral host LC medium, respectively. Knot diagrams and their reconnection sites are presented to illustrate the one-to-one correspondence between a given knot and the confirmed existence of its mirrored counterpart in a medium of opposite handedness. The direction and handedness of the helical chiral nematic background (with helical axis denoted by \({\bf{\chi }}\)) is shown schematically in the first row. Gray (black) lines on schematics refer to the local vortex winding number which is +1/2 (-1/2), as defined in Fig. 2c. Blue and green bands delineate intra- and inter-heliknoton reconnections, respectively. i-iv and v-viii correspond to the simulated left- and right-handed knots, respectively, obtained through re-linking of vortex lines as described above. c, Top row describes a typically observed fusion of two right-handed trefoil knots, while the bottom row depicts a hypothetical reconnection between a right- and left-handed trefoil knots that could produce an achiral knot, albeit such opposite-chirality knots so far could not be stabilized next to one another in left- or right-handed or achiral nematic LCs. Letters “L” and “R” denote left- or right-handedness of respective knots. Below arrows are the corresponding band surgery diagrams of the reconnected knots. Top-right insets show the simplified knots where the bottom-right knot is identified as an achiral knot.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information describing the numerical free-energy minimization and director relaxation protocol.

Supplementary Video 1

Fusion of two heliknotons. Video shows a pair of heliknotons undergoing reconnections visualized by both director-orientation-based coloured vortices and ribbons of splay-bend deformations in the helical axis field around the vortices. The simplified KnotPlot schematics of reconnections are shown in the top row of the inset in the centre. The bottom row of the inset depicts the colour scheme corresponding to \({{\mathbb{S}}}^{2}\) and visualizing director orientations, as well as the scheme defining the ribbons of splay-bend deformations in the helical axis field.

Supplementary Video 2

Heliknoton fusion starting from a linear array. A POM video of an array of initially six separate heliknotons hybridizing into a fused Q = 4 tetramer (left) and Q = 2 dimer (right). The scale bar represents 10 µm; crossed double arrows show the orientations of the crossed polarizers.

Supplementary Video 3

Voltage-induced reconnection of two heliknotons. Video shows the reconnections of two heliknotons. The heliknotons initially have the separation vector orthogonal to the helical axis; however, increasing the voltage displaces the heliknotons vertically causing them to fuse together. This fusion and further evolution of the multi-component link topology through reconnections is shown schematically with KnotPlot diagrams in the central inset’s top row, whereas the bottom row illustrates the colour schemes depicting director orientations and the local vortex winding numbers. The final four-component link obtained after transformation from a three-component link (with the intermediate state in the form of a graph seen in this video) is shown in Fig. 3f,g.

Supplementary Video 4

Fission and fusion of knots approaching along χ0 and z axis. Video shows transformations between a pair of heliknotons separated along the far-field helical axis χ0 (along z axis) switching between two separated trefoil knots and the connected sum of the two trefoils. The simplified KnotPlot diagrams of the states before and after reconnecting are shown in the centre inset’s top row; the bottom row describes the schemes for visualizing coloured director orientations (left) and splay-bend regions in the helical axis field around the vortices.

Supplementary Video 5

Repeated fusion and fission of two heliknotons. Video shows a pair of heliknotons having separation vector tilted relative to the far-field helical axis (and z axis). The simplified KnotPlot schematics of the knots obtained and respective colour schemes (similar to ones used in previous videos) are shown in the central inset.

Supplementary Video 6