Abstract

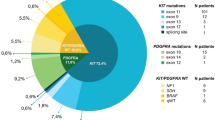

Epigenetic aberrations are widespread in cancer, yet the underlying mechanisms and causality remain poorly understood1,2,3. A subset of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) lack canonical kinase mutations but instead have succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) deficiency and global DNA hyper-methylation4,5. Here, we associate this hyper-methylation with changes in genome topology that activate oncogenic programs. To investigate epigenetic alterations systematically, we mapped DNA methylation, CTCF insulators, enhancers, and chromosome topology in KIT-mutant, PDGFRA-mutant and SDH-deficient GISTs. Although these respective subtypes shared similar enhancer landscapes, we identified hundreds of putative insulators where DNA methylation replaced CTCF binding in SDH-deficient GISTs. We focused on a disrupted insulator that normally partitions a core GIST super-enhancer from the FGF4 oncogene. Recurrent loss of this insulator alters locus topology in SDH-deficient GISTs, allowing aberrant physical interaction between enhancer and oncogene. CRISPR-mediated excision of the corresponding CTCF motifs in an SDH-intact GIST model disrupted the boundary between enhancer and oncogene, and strongly upregulated FGF4 expression. We also identified a second recurrent insulator loss event near the KIT oncogene, which is also highly expressed across SDH-deficient GISTs. Finally, we established a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) from an SDH-deficient GIST that faithfully maintains the epigenetics of the parental tumour, including hypermethylation and insulator defects. This PDX model is highly sensitive to FGF receptor (FGFR) inhibition, and more so to combined FGFR and KIT inhibition, validating the functional significance of the underlying epigenetic lesions. Our study reveals how epigenetic alterations can drive oncogenic programs in the absence of canonical kinase mutations, with implications for mechanistic targeting of aberrant pathways in cancers.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Sequencing data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in GEO with the accession code GSE107447.

References

Kaelin, W. G. Jr & McKnight, S. L. Influence of metabolism on epigenetics and disease. Cell 153, 56–69 (2013).

Jones, P. A. & Baylin, S. B. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell 128, 683–692 (2007).

Flavahan, W. A., Gaskell, E. & Bernstein, B. E. Epigenetic plasticity and the hallmarks of cancer. Science 357, eaal2380 (2017).

Janeway, K. A. et al. Defects in succinate dehydrogenase in gastrointestinal stromal tumors lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 314–318 (2011).

Killian, J. K. et al. Succinate dehydrogenase mutation underlies global epigenomic divergence in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Discov. 3, 648–657 (2013).

Bickmore, W. A. & van Steensel, B. Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell 152, 1270–1284 (2013).

Dixon, J. R. et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012).

Dekker, J. & Mirny, L. The 3D genome as moderator of chromosomal communication. Cell 164, 1110–1121 (2016).

Rao, S. S. et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680 (2014).

Hnisz, D. et al. Activation of proto-oncogenes by disruption of chromosome neighborhoods. Science 351, 1454–1458 (2016).

Xiao, M. et al. Inhibition of α-KG-dependent histone and DNA demethylases by fumarate and succinate that are accumulated in mutations of FH and SDH tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 26, 1326–1338 (2012).

Lu, C. et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature 483, 474–478 (2012).

Bell, A. C. & Felsenfeld, G. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature 405, 482–485 (2000).

Hark, A. T. et al. CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature 405, 486–489 (2000).

Liu, X. S. et al. Editing DNA methylation in the mammalian genome. Cell 167, 233–247.e17 (2016).

Flavahan, W. A. et al. Insulator dysfunction and oncogene activation in IDH mutant gliomas. Nature 529, 110–114 (2016).

Hirota, S. et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 279, 577–580 (1998).

Boikos, S. A. & Stratakis, C. A. The genetic landscape of gastrointestinal stromal tumor lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Endocrine 47, 401–408 (2014).

Taguchi, T. et al. Conventional and molecular cytogenetic characterization of a new human cell line, GIST-T1, established from gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Lab. Invest. 82, 663–665 (2002).

Mumbach, M. R. et al. HiChIP: efficient and sensitive analysis of protein-directed genome architecture. Nat. Methods 13, 919–922 (2016).

Arao, T. et al. FGF3/FGF4 amplification and multiple lung metastases in responders to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 57, 1407–1415 (2013).

Javidi-Sharifi, N. et al. Crosstalk between KIT and FGFR3 promotes gastrointestinal stromal tumor cell growth and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 75, 880–891 (2015).

Li, F. et al. FGFR-mediated reactivation of MAPK signaling attenuates antitumor effects of imatinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Discov. 5, 438–451 (2015).

West, R. B. et al. The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 107–113 (2004).

Pal, S. K. et al. Efficacy of BGJ398, a fibroblast growth factor receptor 1-3 inhibitor, in patients with previously treated advanced urothelial carcinoma with FGFR3 alterations. Cancer Discov. 8, 812–821 (2018).

Janeway, K. A. et al. Sunitinib treatment in pediatric patients with advanced GIST following failure of imatinib. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 52, 767–771 (2009).

Sircar, K. et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal as precursors of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 23, 377–389 (1999).

Gomez-Pinilla, P. J. et al. Ano1 is a selective marker of interstitial cells of Cajal in the human and mouse gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296, G1370–G1381 (2009).

Singh, R. D. et al. Ano1, a Ca2+-activated Cl- channel, coordinates contractility in mouse intestine by Ca2+ transient coordination between interstitial cells of Cajal. J. Physiol. 592, 4051–4068 (2014).

Urbini, M. et al. Gain of FGF4 is a frequent event in KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/RAS-P WT GIST. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 58, 636–642 (2019).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Heinz, S. et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010).

Whyte, W. A. et al. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 153, 307–319 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Ooi, W. F. et al. Epigenomic profiling of primary gastric adenocarcinoma reveals super-enhancer heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 7, 12983 (2016).

Cohen, A. J. et al. Hotspots of aberrant enhancer activity punctuate the colorectal cancer epigenome. Nat. Commun. 8, 14400 (2017).

McDonald, O. G. et al. Epigenomic reprogramming during pancreatic cancer progression links anabolic glucose metabolism to distant metastasis. Nat. Genet. 49, 367–376 (2017).

Hovestadt, V. et al. Decoding the regulatory landscape of medulloblastoma using DNA methylation sequencing. Nature 510, 537–541 (2014).

Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 16, 259 (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. Exploring long-range genome interactions using the WashU Epigenome Browser. Nat. Methods 10, 375–376 (2013).

Phanstiel, D. H. Sushi: Tools for visualizing genomics data. R package version 1.16.0. https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/Sushi.html (2019).

Lareau, C. A. & Aryee, M. J. hichipper: a preprocessing pipeline for calling DNA loops from HiChIP data. Nat. Methods 15, 155–156 (2018).

Splinter, E., de Wit, E., van de Werken, H. J., Klous, P. & de Laat, W. Determining long-range chromatin interactions for selected genomic sites using 4C-seq technology: from fixation to computation. Methods 58, 221–230 (2012).

van de Werken, H. J. et al. Robust 4C-seq data analysis to screen for regulatory DNA interactions. Nat. Methods 9, 969–972 (2012).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Hemming, M. L. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor enhancers support a transcription factor network predictive of clinical outcome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E5746–E5755 (2018).

Wagner, G. P., Kin, K. & Lynch, V. J. Measurement of mRNA abundance using RNA-seq data: RPKM measure is inconsistent among samples. Theory Biosci. 131, 281–285 (2012).

GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 45, 580–585 (2013).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Grant, C. E., Bailey, T. L. & Noble, W. S. FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27, 1017–1018 (2011).

Mathelier, A. et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D142–D147 (2014).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Abyzov, A., Urban, A. E., Snyder, M. & Gerstein, M. CNVnator: an approach to discover, genotype, and characterize typical and atypical CNVs from family and population genome sequencing. Genome Res. 21, 974–984 (2011).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Wagle, M. C. et al. A transcriptional MAPK pathway activity score (MPAS) is a clinically relevant biomarker in multiple cancer types. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 7, 2 (2018).Correct publication information for this reference?

Chi, P. et al. ETV1 is a lineage survival factor that cooperates with KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Nature 467, 849–853 (2010).

Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

Manning, G., Whyte, D. B., Martinez, R., Hunter, T. & Sudarsanam, S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298, 1912–1934 (2002).

Yu, G. et al. ggtree: an R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 28–36 (2017).

ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012).

Lee, M. Y. et al. Transcriptome of interstitial cells of Cajal reveals unique and selective gene signatures. PLoS One 12, e0176031 (2017).

Killian, J. K. et al. Recurrent epimutation of SDHC in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 268ra177 (2014).

Tang, C. M. et al. Hedgehog pathway dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of human gastrointestinal stromal tumors via GLI-mediated activation of KIT expression. Oncotarget 7, 78226–78241 (2016).

Ostrowski, J. et al. Functional features of gene expression profiles differentiating gastrointestinal stromal tumours according to KIT mutations and expression. BMC Cancer 9, 413 (2009).

Astolfi, A. et al. A molecular portrait of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an integrative analysis of gene expression profiling and high-resolution genomic copy number. Lab. Invest. 90, 1285–1294 (2010).

Gautier, L., Cope, L., Bolstad, B. M. & Irizarry, R. A. affy—analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics 20, 307–315 (2004).

Li, Z. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell 15, 501–513 (2009).

Murakami, A. et al. Hypoxia increases gefitinib-resistant lung cancer stem cells through the activation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. PLoS One 9, e86459 (2014).

Bosch-Marce, M. et al. Effects of aging and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity on angiogenic cell mobilization and recovery of perfusion after limb ischemia. Circ. Res. 101, 1310–1318 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Gillespie, M. Miri, F. Najm, P. van Galen and E. Choy for assistance with clinical samples and analysis, H. Gu and A. Gnirke for sequencing assistance, and E. Gaskell for discussions. W.A.F. is supported by an F32 from the National Cancer Institute. Y.D. is supported by the Tosteson Postdoctoral Fellowship. B.E.B. is the Bernard and Mildred Kayden Endowed MGH Research Institute Chair and an American Cancer Society Research Professor. This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the NIH Common Fund, the Starr Cancer Consortium, and the Ludwig Center at Harvard.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and experimental design: W.A.F., Y.D., S.E.J., M.L.H., E.T.S., G.D.D. and B.E.B. Methodology and data acquisition: W.A.F., Y.D., S.E.J., M.L.H., D.R.T., E.H., S.J.S., N.M.J., C.P.R., B.K.E., P.C.G., J.L.H., E.T.S., G.D.D. and B.E.B. Analysis and interpretation of data: W.A.F., Y.D., M.L.H., S.J.S., N.M.J., G.D.D. and B.E.B. Manuscript writing and revision: W.A.F., Y.D. and B.E.B.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.E.B. is an advisor and equity holder for Fulcrum Therapeutics, 1CellBio, HiFiBio and Arsenal Biosciences, is an advisor for Cell Signaling Technologies, and has equity in Nohla Therapeutics. G.D.D. reports relationships with Novartis, Bayer, Pfizer, EMD-Serono, Sanofi, Ignyta, Roche, Loxo Oncology, AbbVie, Mirati Therapeutics, Epizyme, Daiichi-Sankyo, WIRB Copernicus Group, ZioPharm, Polaris Pharmaceuticals, M.J. Hennessey / OncLive, Adaptimmune, GlaxoSmithKline, Blueprint Medicines, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, G1 Therapeutics, CARIS Life Sciences, Bessor Pharmaceuticals, ERASCA Pharmaceuticals, CHAMPIONS Oncology, Janssen, PharmaMar; in addition, G.D.D. has a Use patent on imatinib for GIST, licensed to Novartis, with royalties paid to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peer review information Nature thanks Christian Frezza, Michael Heinrich, Michael Rehli and Peter Scacheri for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Epigenomic characterization of GIST.

a, ChIP–seq profiles for H3K27ac were compared for GIST specimens and other gastrointestinal tract tumour specimens (GAC, gastric adenocarcinoma; CRC, colorectal cancer; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma). Heat map depicts pairwise Pearson correlations between the top 10,000 most variable peaks (yellow indicates high correlation; blue indicates low correlation). The dendrogram (left) was derived by unweighted average distance linkage. Enhancer patterns are relatively consistent across GIST subtypes, compared to other tumour types. b, DNA methylation levels in the vicinity of CTCF sites were profiled genome-wide by hybrid-selection bisulfite sequencing. CTCF sites are binned according to the amount their methylation increased in SDH-deficient GISTs, relative to SDH-intact GISTs (methylation change computed over a 250 bp window centred on the motif). For each bin, bar graphs depict the percentage of sites that lose CTCF binding in SDH-deficient GISTs, per ChIP–seq. Separate plots are shown for CTCF sites for which motifs do or do not contain a CpG. Increased methylation over CTCF sites is associated with more frequent loss of CTCF binding, even when the CTCF motif lacks a CpG. c, Plot depicts correlation between CTCF occupancy and DNA methylation in SDH-deficient GISTs. Red points show Spearman correlations between CTCF ChIP–seq signal and methylation of CpGs at indicated positions relative to the centre of the CTCF motif. Red line reflects correlation to average methylation over 10 bp windows. Randomly permuted data (black) are shown for comparison. Anti-correlation between CTCF occupancy and methylation is evident over a ~250-bp binding footprint. d, Genomic views of a representative 10 Mb region on chromosome 21 depict chromosome topology (HiC, red), CTCF binding (ChIP–seq, orange) and CTCF–CTCF loop interactions (HiChIP, black) for the SDH-intact GIST model, GIST-T1. TADs are visible as triangles of enhanced interaction in HiC data, flanked by boundaries that correspond to loop interactions in HiChIP data. Genes (blue) are also indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Super-enhancers and insulators in GIST.

a, Traces depict H3K27ac ChIP–seq signal for normal stomach muscle (NSM) and GISTs of the indicated subtype over the FGF–ANO1 locus. b, Traces depict H3K27ac ChIP–seq signal for NSM and GISTs of the indicated subtype over the PDGFRA–KIT locus. Genes are indicated in blue, and super-enhancer locations are indicated by green bars. For a, b, traces are representative of 11 KIT-mutant and 6 SDH-deficient tumours with similar results. c, Traces depict CTCF binding over the FGF insulator in normal stomach muscle (NSM) and GIST clinical specimens. d, Plot depicts CTCF ChIP–seq signal over the strongest CTCF peak in the FGF insulator in normal stomach muscle (NSM, n = 4), and KIT mutant (n = 11), PDGFRA mutant (n = 2) and SDH-deficient GISTs (n = 6). e, Traces depict CTCF binding over the KIT insulator in normal stomach muscle (NSM) and GIST clinical specimens. f, Plot depicts CTCF ChIP–seq signal over the strongest CTCF peak in the KIT insulator in normal stomach muscle (NSM, n = 4), and KIT mutant (n = 11), PDGFRA mutant (n = 2) and SDH-deficient GISTs (n = 6). For d and f, horizontal bars reflect mean values and P values indicate significance of CTCF loss in SDH-deficient GIST, as determined by the Walt test (via DEseq254). All n values represent the number of biologically independent clinical specimens.

Extended Data Fig. 3 FGF locus 4C-seq data and insulator deletion.

a, Traces depict 4C-seq data at FGF locus, as in Fig. 2b, except graphed on the same axis to allow for direct comparison. b, c, Bar plots quantify 4C-seq interactions between the super-enhancer viewpoint and FGF4 (b) or FGF3 (c). Expression of these genes in the corresponding SDH-deficient GIST specimens is also shown. d, Traces depict CTCF ChIP–seq signal in GIST-T1 cells infected with CRISPR–Cas9 and either a control sgRNA directed at GFP (black, top) or sgRNAs directed against the two indicated CTCF motifs in the FGF insulator (second row, red).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Allelic imbalance in FGF3 and FGF4 activation.

a, Two heterozygous SNPs in FGF4 (both 3′ UTR) enabled us to evaluate allelic expression in three SDH-deficient GISTs (tumours S6, S1 and S4). Both alleles for each SNP were detected in DNA sequencing data for these tumours, but only one allele was detected in RNA-seq data of tumours S1 and S6, indicative of mono-allelic FGF4 expression. Both alleles are detected in tumour S4, indicating bi-allelic expression of FGF4. b, Heterozygous SNPs in FGF3 exons (both synonymous base substitutions) enabled us to evaluate allelic expression in the SDH-deficient GISTs (tumours S2 and S5). In both cases, DNA sequencing confirmed heterozygosity at the genome level (C/A and T/C, respectively), but RNA-seq data demonstrated mono-allelic FGF3 expression. c, Both alleles of heterozygous SNPs in ANO1 exons were found in the RNA-seq data derived from SDH-deficient GIST samples, confirming bi-allelic expression of ANO1. Similarly, both alleles of heterozygous SNPs were found in the histone H3K27ac ChIP–seq data, confirming the bi-allelic nature of the super-enhancer (not shown). d, One SDH-deficient GIST sample was heterozygous for a SNP (rs386829467) located about 50 bp from the CTCF motif of Peak 2 in the FGF insulator. Allele-agnostic methylation data confirmed 43% methylation of the CTCF peak in this tumour, while essentially no methylation was detected in the SDH-intact tumours (left). Separation of the two alleles using the heterozygous SNP revealed strong allelic bias in the SDH-deficient tumour: one allele was largely unmethylated (~3% methylation), while the other was highly methylated (~75% methylation), consistent with mono-allelic methylation of the CTCF site (right). e, Schematic depicts 4C-seq experimental protocol and primer design for detecting SNPs. DNA elements in close physical proximity are crosslinked and restricted with an enzyme that leaves nucleotide overhangs. These overhangs are then proximity ligated to crosslinked fragments. A second restriction enzyme (with different restriction sites) is then used to circularize the ligated fragments, allowing for inverse PCR. Here we selected restriction enzymes and designed a custom read 2 primer to capture a heterozygous SNP within the super-enhancer. This second read is normally non-informative as contact frequencies are determined through the viewpoint primer (read 1), but in this case enabled us to detect the SNP and assign each ligated fragment to a specific allele. f, The left trace (grey) depicts standard 4C-seq data (allele agnostic), which demonstrates strong interaction between super-enhancer viewpoint and FGF4. However, the SNP covered in the non-viewpoint read enabled us to distinguish interactions involving the minor (top right) or major (bottom right) allele. This revealed that the major allele (purple) is responsible for ~97% of super-enhancer–FGF4 interactions.

Extended Data Fig. 5 KIT locus 4C-seq data and insulator deletion.

a, Traces depict KIT locus 4C-seq data, as in Fig. 3b, except graphed on the same axis to allow for direct comparison. b–d, Bar plots quantify 4C-seq interactions (top, reproduced from Fig. 3b) between the super-enhancer viewpoint and positions within the super-enhancer TAD (b), sequences just beyond the KIT insulator (c), or the KIT gene itself (d). P values indicate significance of difference between SDH-intact and SDH-deficient, by two-sided t-test. e, Traces depict CTCF ChIP–seq signal in GIST-T1 cells infected with Cas9 and either a control sgRNA directed at GFP (black, top) or sgRNAs directed against the two bound CTCF motifs in the KIT insulator (second row, red).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Hypoxia marker induction in GIST-T1 cells.

a, Bar plot depicts levels of the TET product, 5-hydroxymethyl-cytosine (5-hmC), measured by ELISA in GIST-T1 cells infected with CRISPR–Cas9 and either a short guide RNA targeting GFP (sgGFP) or SDHB. Cells were cultured in either control media or media supplemented with 20 μM of dimethylsuccinate (DMS), a membrane-permeable ester of succinate, for 3 days, as indicated. b, c, Plots show relative expression of pseudo-hypoxia-associated genes EPAS1 (also known as HIF2A)67 and IGF1R68 (b), and KITLG (also known as SCF)69 (c) in control GIST-T1 cells (black), SDH-deficient GIST-T1 cells generated by CRISPR–Cas9 knockout of SDHB and cultured with exogenous succinate (red), or GIST-T1 cells treated with the iron chelator DFX to simulate hypoxia (blue). Upregulation of KIT ligand due to pseudo-hypoxia or tumour hypoxia may supplement FGF ligands in promoting RTK signalling in SDH-deficient GIST.

Extended Data Fig. 7 FGF and KIT insulator methylation and expression in GIST subtypes and non-malignant cells.

a, Bar plot depicts methylation of FGF insulator CTCF peak 2 (top) and KIT insulator CTCF peak 2 (bottom) in 34 tissues and primary cells available through ENCODE60. Values are average methylation of CpGs nearest the CTCF motifs, determined by whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) (KIT insulator, 3 CpGs; FGF insulator, 6 CpGs). Methylation of these sites is also shown for SDH-intact and SDH-deficient GISTs (see Fig. 3e, f), and for flow-sorted CD45−ANO1+KIT+ (ICC enriched) cells from normal stomach muscle (NSM) tissue (n values represent biologically independent specimens). b, Left, table depicts FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) values of relevant genes in mouse ICCs isolated from jejunum or colon61. Right, dot plot depicts expression of FGF4 in either flow sorted ICCs (green) or GISTs of the indicated subtype: KIT mutant in black, PDGFRA mutant in blue, SDH-deficient in red, and KIT-/PDGFRA wild type in purple62,63,64,65,66. SDH status of the latter group is unknown, but SDH-deficient GIST represent a significant portion of KIT-/PDGFRA wild-type tumours. Data are drawn from the indicated GEO series and publications.

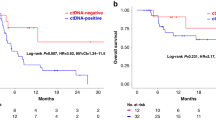

Extended Data Fig. 8 PDX trial of FGFR and KIT combination therapy in SDH-deficient GIST.

a, b, Genomic views depict RNA expression (black), H3K27ac (green) and CTCF occupancy (orange) over the FGF (a) and KIT (b) loci for the S1 primary tumour and PDX. Genes (blue), super-enhancers (green bar and shade) and lost CTCF insulators (orange shade) are indicated. c, Plot depicts tumour volume during treatment and observation periods of experiment, as in Fig. 4g, except with time axis extended until final group reached censor point (one tumour in the group >2,000 mm3). Points represent mean tumour size, error bars represent s.e.m., and shading represents range of tumour sizes for n = 8 biologically independent xenograft-bearing mice per group. For statistics, see Fig. 4g. d, Kaplan–Meier plot depicts survival until clinical endpoint (tumour size >2,000 mm3) for the same PDX trial. Median and range survival are indicated for each group. P values reflect difference in survival between groups as calculated by logrank test.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information Table 1

| Clinical Specimens Analysed Table lists all of the clinical specimens analysed in the manuscript, noting tissue type, source (FFPE vs. fresh frozen), primary site and metastatic status (if known), driver mutations (if known), and experiments performed on the tissue. For FFPE tissue, no genetic testing was performed; instead SDH status was determined by IHC

Supplementary Information Table 2

| Candidate deregulated genes due to insulator loss Table lists results of analysis of genes potentially regulated by insulator loss (see Fig. 1e). Listed are methylation difference at lost insulators and median expression in GIST of various driver mutations

Supplementary Information Table 3

| PDX Tumor Growth Data Table lists measured volumes of Patient Derived Xenograft (PDX) trial (see Fig. 4f, g, Extended Data Fig. 8.) Volumes are listed as mm3 with each column representing serial measurements of a single biologically-independent PDX-bearing mouse; for further details of study, see Methods

Supplementary Information Table 4

| ChIP–seq information Table lists information from ChIPseq runs associated with the work, including sample, antibody, processed data file name(s), instrument, read count, and sequencing strategy (e.g. paired/single end)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flavahan, W.A., Drier, Y., Johnstone, S.E. et al. Altered chromosomal topology drives oncogenic programs in SDH-deficient GISTs. Nature 575, 229–233 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1668-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1668-3

This article is cited by

-

Epigenetic priming promotes tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance and oncogene amplification

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2026)

-

Mitochondrial electron transport chain gene-based prognostic model identifies SDHB as a key regulator of low-grade glioma progression and therapeutic target

Cancer Cell International (2025)

-

CREPT is required for the metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer through a co-operational-chromatin loop-based gene regulation

Molecular Cancer (2025)

-

Editing DNA methylation in vivo

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Olverembatinib, a multikinase inhibitor that modulates lipid metabolism, in advanced succinate dehydrogenase-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a phase 1b study and translational research

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2025)

DR Gaurav Dixit

Hi,

Thank for this article, This article would help people who are seeking help or knowledge as well.

Dr Gaurav Dixit

BMT Physician & the Best Hematologist in Delhi

https://www.drgauravdixit.com/

Arturo Tozzi cns

UNDERRATED TOPOLOGICAL APPROACHES, APART FROM THE EVERY-DAY NETWORK CONNECTIVITY

Recent papers provide topological accounts of countless physical and biological phenomena, such as gene topology (Flavahan et al., 2019; Achar et al, 2020), hidden symmetries (Golubitsky and Stewart, 2015), phase transitions (Pettini et al., 2019), unconventional superconductivity (Cao et al., 2018), quantum computing (Collins, 2006), coupled oscillators’synchronization (Arenas et al., 2008), HIV proteins arrangement (Gaiha et al. 2019), receptor dimerization (Mohan et al., 2019). Thanks to its ability to assess systems’ properties in terms of abstract mathematical spaces (Dodson and Parker, 1997), topology is generally used in the context of complex network analysis and graph theory (Kleinberg et al., 2016), looking for, e.g., integrated network topology connectivity ((Fukushima et al. 201), multilevel entropy measures (Maletić and Zhao, 2017), and simplicial complexes (Giusti et al., 2016; Bianconi and Rahmede, 2016) that capture emergent community structures. In the current accounts, the value of topology mostly rests on the possibility to assess modifications in elusive networks subtending systems dynamics, such as transitions from star to mesh arrangements, or from ring to tree.

Nevertheless, topological changes in biological systems might be used in another, underrated way: by using theorems from algebraic topology. These frequently underrated theorems are useful to assess countless physical and biological dynamics. To provide an example, the Hairy ball theorem (HBT) (that informally states that “given at least some wind on Earth, there must at all times be a cyclone or anticyclone somewhere”) has been used to describe unconventional type-II superconductors (Laver and Forgan, 2010), and surface instabilities of liquid/vapor interfaces (Bormashenko, 2015). We refer the reader to Tozzi et al. (2017) for a survey of the countless applications of the Borsuk-Ulam theorem (“at any moment, there is always a pair of antipodal points on the Earth’s surface with equal temperatures and barometric pressures”), that stands for an unidersal principle underlying countless features from far-flung scientific disciplines. Also the ham sandwich theorem (“given globs of ham, bread, and cheese, placed any way you like, there exists one flat slice of a knife that will bisect each of the ham, bread, and cheese”), the Brouwer fixed-point theorem ( “no matter how you slosh the coffee, some point is always in the same position that it was before the sloshing began”) and the Lusternik–Schnirelmann theorem (“every time you split a sphere in three parts, one of the three must encompass an entire diameter”) display physical and biological counterparts.

In physical/biological systems, the occurrence of such algebraic theorems leads to a straightforward observation: tiny changes in topological features lead to alterations in macroscopic behavior. To provide an example that demonstrates how small modifications in topology may lead to novel functional biological features, take a perfectly spherical soap bubble. In its spherical surface, due to the Borsuk-Ulam theorem, there must exist at least two antipodal points with identical values of surface tension. When the soap bubble is deformed, the spherical shape gets lost: this leads to the disappearance of antipodal points with the same surface tension.

REFERENCES

1)Achar YJ, Adhil M, Choudhary r, Gilbert N, Foiani M. 2020. Negative supercoil at gene boundaries modulates gene topology. Nature 577: 701–705.

2)Arenas, A., Díaz-Guilera, A., Kurths, J., Moreno, Y., Zhou, C. 2008. Synchronization in complex networks. Phys. Rep. 469, 93-153.

3)Bianconi G, Rahmede C. 2016. Network geometry with flavor: From complexity to quantum geometry. Phys Rev E. 2016 Mar;93(3):032315. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.93.032315.

4)Bormashenko E. 2015. Surface instabilities and patterning at liquid/vapor interfaces: Exemplifications of the “hairy ball theorem”. Colloids and Interface Science Communications. Volume 5, March 2015, Pages 5-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.c....

5)Borsuk K. 1933. Dreisatzeuber die n-dimensionale euklidischesphare. FundamentaMathematicae, XX, 177–190.

6)Cao Y, Fatemi V, Fang S, Watanabe K, Taniguchi T, et al. 2018. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature volume 556, 43–50.

7)Collins, G. P. 2006. Computing with quantum knots. Scientific American, 294(4), 56-63.

8)Dodson CTJ, Parker PE. 1997. A user’s guide to algebraic topology, Kluwer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1997. ISBN: 0-7923-4292-5, MR1430097.

9)Flavahan WA, Drier Y, Johnstone SE, Hemming ML, Tarjan DR, et al. 2019. Altered chromosomal topology drives oncogenic programs in SDH-deficient GISTs. Nature, 575: 229–233.

10)Fukushima M, Betzel RF, He Y, van den Heuvel MP, Zuo XN, Sporns O. 2017. Structure-function relationships during segregated and integrated network states of human brain functional connectivity. Brain Struct Funct. 2017 Oct 31. doi: 10.1007/s00429-017-1539-3.

11)Gaiha GD, Rossin EJ, Urbach J, Landeros C, Collins DR, et al. 2019. Structural topology defines protective CD8+ T cell epitopes in the HIV proteome. Science, 3;364(6439):480-484. doi: 10.1126/science.aav5095.

12)Giusti C, Ghrist R, Bassett D.2016. Two's company, three (or more) is a simplex : Algebraic-topological tools for understanding higher-order structure in neural data.JComputNeurosci. 2016 Aug;41(1):1-14. doi: 10.1007/s10827-016-0608-6.

13)Golubitsky, M., Stewart, I. (2015). Recent advances in symmetric and network dynamics. Chaos, 25(9), 097612.

14)Kleineberg K-K, Boguñá M, Ángeles Serrano M, Papadopoulos F. 2016. Hidden geometric correlations in real multiplex networks. Nature Physics (12) 1076–1081. doi:10.1038/nphys3812.

15)Laver M, Forgan EM. 2010. Magnetic flux lines in type-II superconductors and the 'hairy ball' theorem. Nature Communications volume 1, Article number: 45.

16)Maletić S, Zhao Y. 2017. Multilevel Integration Entropies: The Case of Reconstruction of Structural Quasi-Stability in Building Complex Datasets. April 2017Entropy 19(4):172. DOI10.3390/e19040172.

17)Mohan K, Ueda G, Kim AR, Jude KM, Fallas AJ, et al. 2019. Topological control of cytokine receptor signaling induces differential effects in hematopoiesis. Science, Vol. 364, Issue 6442, eaav7532. DOI: 10.1126/science.aav7532.

18)Pettini, G., Gori, M., Franzosi, R., Clementi, C., & Pettini, M. 2019. On the origin of phase transitions in the absence of symmetry-breaking. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 516, 376-392.

19)Tozzi A, Peters JF, Fingelkurts AA, Fingelkurts AA, Marijuán PC. 2017. Topodynamics of metastable brains. Physics of Life Reviews, 21, 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j....

Arturo Tozzi

Center for Nonlinear Science, Department of Physics, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas, USA

tozziarturo@libero.it

Arturo.Tozzi@unt.edu