Abstract

Bridge-like lipid-transport proteins (BLTPs) are an evolutionarily conserved family of proteins that localize to membrane-contact sites and are thought to mediate the bulk transfer of lipids from a donor membrane, typically the endoplasmic reticulum, to an acceptor membrane, such as that of the cell or an organelle1. Although BLTPs are fundamentally important for a wide array of cellular functions, their architecture, composition and lipid-transfer mechanisms remain poorly characterized. Here we present the subunit composition and the cryogenic electron microscopy structure of the native LPD-3 BLTP complex isolated from transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. LPD-3 folds into an elongated, rod-shaped tunnel of which the interior is filled with ordered lipid molecules that are coordinated by a track of ionizable residues that line one side of the tunnel. LPD-3 forms a complex with two previously uncharacterized proteins, one of which we have named Spigot and the other of which remains unnamed. Spigot interacts with the N-terminal end of LPD-3 where lipids are expected to enter the tunnel, and experiments in multiple model systems indicate that Spigot has a conserved role in BLTP function. Our LPD-3 complex structural data reveal protein–lipid interactions that suggest a model for how the native LPD-3 complex mediates bulk lipid transport and provides a foundation for mechanistic studies of BLTPs.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The volumes for the cryo-EM data have been deposited at the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession codes EMD-45276 (full-length) and EMD-45399 (N-terminal). The coordinates of the LPD-3 complex have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank under accession code 9CAP. The full version of the silver-stain gel is included in Supplementary Fig. 1, and the sequences for all RNAi constructs are included in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The UniProt accession number for LPD-3 is A0A0K3AWP8. The UniProt accession number for Spigot is Q4W5H0. The UniProt accession number for LTAP2 is U4PLN7. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Neuman, S. D., Levine, T. P. & Bashirullah, A. A novel superfamily of bridge-like lipid transfer proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 32, 962–974 (2022).

Casares, D., Escriba, P. V. & Rossello, C. A. Membrane lipid composition: effect on membrane and organelle structure, function and compartmentalization and therapeutic avenues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2167 (2019).

Blom, T., Somerharju, P. & Ikonen, E. Synthesis and biosynthetic trafficking of membrane lipids. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a004713 (2011).

Jackson, C. L., Walch, L. & Verbavatz, J. M. Lipids and their trafficking: an integral part of cellular organization. Dev. Cell 39, 139–153 (2016).

Wong, L. H., Gatta, A. T. & Levine, T. P. Lipid transfer proteins: the lipid commute via shuttles, bridges and tubes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 85–101 (2019).

Schauder, C. M. et al. Structure of a lipid-bound extended synaptotagmin indicates a role in lipid transfer. Nature 510, 552–555 (2014).

Hanna, M., Guillen-Samander, A. & De Camilli, P. RBG motif bridge-like lipid transport proteins: structure, functions, and open questions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 39, 409–434 (2023).

Li, P., Lees, J. A., Lusk, C. P. & Reinisch, K. M. Cryo-EM reconstruction of a VPS13 fragment reveals a long groove to channel lipids between membranes. J. Cell Biol. 219, e202001161 (2020).

Hanna, M. G., Suen, P. H., Wu, Y., Reinisch, K. M. & De Camilli, P. SHIP164 is a chorein motif lipid transfer protein that controls endosome–Golgi membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 221, e202111018 (2022).

Osawa, T. et al. Atg2 mediates direct lipid transfer between membranes for autophagosome formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 281–288 (2019).

Kumar, K., Bellad, A., Prasad, P., Girimaji, S. C. & Muthusamy, B. KIAA1109 gene mutation in surviving patients with Alkuraya-Kučinskas syndrome: a review of literature. BMC Med. Genet. 21, 136 (2020).

Toulmay, A. et al. Vps13-like proteins provide phosphatidylethanolamine for GPI anchor synthesis in the ER. J. Cell Biol. 221, e202111095 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. A conserved megaprotein-based molecular bridge critical for lipid trafficking and cold resilience. Nat. Commun. 13, 6805 (2022).

John Peter, A. T., Cheung, N. J. & Kornmann, B. Csf1: a putative lipid transport protein required for homeoviscous adaptation of the lipidome. Contact 5, 25152564221101974 (2022).

Tokai, M., Kawasaki, H., Kikuchi, Y. & Ouchi, K. Cloning and characterization of the CSF1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is required for nutrient uptake at low temperature. J. Bacteriol. 182, 2865–2868 (2000).

Verstreken, P. et al. Tweek, an evolutionarily conserved protein, is required for synaptic vesicle recycling. Neuron 63, 203–215 (2009).

Kang, Y. J. et al. Tweek-dependent formation of ER-PM contact sites enables astrocyte phagocytic function and remodeling of neurons. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.06.565932 (2023).

Kumar, N. et al. VPS13A and VPS13C are lipid transport proteins differentially localized at ER contact sites. J. Cell Biol. 217, 3625–3639 (2018).

Clark, S., Jeong, H., Goehring, A., Kang, Y. & Gouaux, E. Large-scale growth of C. elegans and isolation of membrane protein complexes. Nat. Protoc. 18, 2699–2716 (2023).

Jeng, E. E. et al. Systematic identification of host cell regulators of Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis using a genome-wide CRISPR screen. Cell Host Microbe 26, 551–563 (2019).

Kumar, R., Kumari, B. & Kumar, M. Prediction of endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins using fragmented amino acid composition and support vector machine. PeerJ 5, e3561 (2017).

Valverde, D. P. et al. ATG2 transports lipids to promote autophagosome biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 218, 1787–1798 (2019).

Adlakha, J., Hong, Z., Li, P. & Reinisch, K. M. Structural and biochemical insights into lipid transport by VPS13 proteins. J. Cell Biol. 221, e202202030 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Structural basis for lipid transfer by the ATG2A–ATG9A complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 32, 35–47 (2025).

Braschi, B., Bruford, E. A., Cavanagh, A. T., Neuman, S. D. & Bashirullah, A. The bridge-like lipid transfer protein (BLTP) gene group: introducing new nomenclature based on structural homology indicating shared function. Hum. Genom. 16, 66 (2022).

Srinivasan, S., Alvarez, D., John Peter, A. T. & Vanni, S. Unbiased MD simulations identify lipid binding sites in lipid transfer proteins. J. Cell Biol. 223, e202312055 (2024).

Tristram-Nagle, S., Petrache, H. I. & Nagle, J. F. Structure and interactions of fully hydrated dioleoylphosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biophys. J. 75, 917–925 (1998).

Hallgren, J. T. et al. DeepTMHMM predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.08.487609 (2022).

Szumowski, S. C. et al. Small GTPases promote actin coat formation on microsporidian pathogens traversing the apical membrane of Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal cells. Cell Microbiol. 18, 30–45 (2016).

Chang, C. L. et al. Feedback regulation of receptor-induced Ca2+ signaling mediated by E-Syt1 and Nir2 at endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions. Cell Rep. 5, 813–825 (2013).

Bean, B. D. M. et al. Competitive organelle-specific adaptors recruit Vps13 to membrane contact sites. J. Cell Biol. 217, 3593–3607 (2018).

Gomez-Sanchez, R. et al. Atg9 establishes Atg2-dependent contact sites between the endoplasmic reticulum and phagophores. J. Cell Biol. 217, 2743–2763 (2018).

Gueneau, L. et al. KIAA1109 variants are associated with a severe disorder of brain development and arthrogryposis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102, 116–132 (2018).

Pei, J., Tang, M. & Grishin, N. V. PROMALS3D web server for accurate multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W30–W34 (2008).

Eng, J. K., Jahan, T. A. & Hoopmann, M. R. Comet: an open-source MS/MS sequence database search tool. Proteomics 13, 22–24 (2013).

Wilmarth, P. A., Riviere, M. A. & David, L. L. Techniques for accurate protein identification in shotgun proteomic studies of human, mouse, bovine, and chicken lenses. J. Ocul. Biol. Dis. Inform. 2, 223–234 (2009).

Keller, A., Nesvizhskii, A. I., Kolker, E. & Aebersold, R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 74, 5383–5392 (2002).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 (2010).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 58, 1948–1954 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank P. A. Karplus for help with structure analysis and manuscript preparation; E. Gouaux and the members of the Gouaux laboratory for discussions; A. Reddy for MS analysis; F. Jalali-Yazdi for help with cryo-EM data processing; Z. Zhou for providing the lpd-3 RNAi construct; and T. Evans for help with C. elegans RNAi experiments. This work was supported by Howard Hughes Medical Institute funding to E. Gouaux; Oregon State University startup funds to S.C.; US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K99 NS126642 to Y.K.; and NIH grants R37 NS053538-18 and R01 NS124146-01 to M.F. A portion of this research was supported by NIH grant R24GM154185 and was performed at the Pacific Northwest Center for Cryo-EM with assistance from M. Miletto. The OHSU Proteomics Shared Resource is partially supported by NIH core grants P30EY010572 and P30CA069533.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. performed the cryo-EM experiments. Y.K. and A.J. performed the RNAi screen and astrocyte-mediated phagocytosis assays in Drosophila. Y.K. generated the constructs for cell culture experiments and K.S.L. performed the experiments. Y.K. performed the worm RNAi experiments in C. elegans. M.P. provided guidance and training for C. elegans experiments. H.L. performed functional analyses of transgenic worm lines. Y.K., M.F. and S.C. designed the project and wrote the manuscript. All of the authors contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Stefano Vanni, Osamu Nureki and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Development and cold tolerance of wild type and transgenic worms.

a, Percentages of animals that reached developmental L4 stage at indicated hours post egg preparation in wild type (WT) worms, lpd3::mvenus worms, or mvenus::lpd3 worms. b, Percentages of animals that survived cold exposure (4 °C for 20 h) post egg preparation in wild type (WT) worms, lpd3::mvenus worms, or mvenus::lpd3 worms. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns=not significant. Values are means +/− S.D. (two-sided unpaired t-test, N = 9 biological replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Isolation of LPD-3 from C. elegans.

a, Spectral confocal image of mVenus fluorescence in an lpd3::mvenus worm showing fluorescence throughout the worm body. Shown is one representative image of six total images. b, Representative FSEC profile of the LPD-3 complex, detected via tryptophan fluorescence. c, A silver stained SDS-PAGE gel of the purified LPD-3 complex. Teal asterisk indicates LPD-3. Other bands may correspond to transiently associated proteins or contaminants. The experiment was repeated two times with similar results. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. d, Mass spectrometry analysis of the purified LPD-3 complex, showing the three proteins with the highest peptide spectral counts (pSC).

Extended Data Fig. 3 RNAi screen in Drosophila.

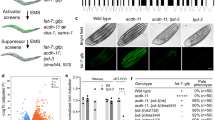

a, Mass spectrometry analysis of the LPD-3 complex, showing the proteins that were subjected to RNAi-mediated knockdown in Drosophila astrocytes to in order to identify regulators of phagocytosis. Y38C1AA.12 lacks a gene name in C. elegans and is referred to in this text as LTAP2. pSC = peptide spectral counts. For the sequences of each RNAi construct, see Supplementary Table 2. b, Overview of vCrz neuron morphology: Eight pairs of vCrz neurons are present in the ventral nerve cord, red dotted box represents imaged region. c, vCrz neuronsat the wandering third instar larval stage (wL3) in controls which is broken down and fully cleared by astrocytes at head eversion (HE, ~12 h after puparium formation) in controls. Astrocyte knockdown of spigot (CG6665) with GMR25H07-Gal4 (astrocyte-specific driver) does not affect neuronal morphology at wL3 but disrupts the ability of astrocytes to clear neuronal debris by HE. vCrz neurons were labelled with anti-Crz, and all images are maximum Z projections of the entire ventral nerve cord (VNC). Scale bar, 50 μm. d, Quantification of data from (c) for controls (UAS-FLP5.DD) (wL3, N = 7; HE, N = 12) and UAS-spigot RNAi (wL3, N = 12; HE, N = 5). Graphs show mean ± SEM, and each dot represents independent animals. Statistical comparisons were performed using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. ****P < 0.0001, ns=not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cryo-EM data analysis of the LPD-3 complex.

Flow chart for cryo-EM data analysis of the LPD-3 “N-terminal” map and “full-length” map. Scale bar of cryo-EM micrograph = 200 Å.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cryo-EM statistics, angular distributions, and selected sections of density maps.

a, N-terminal cryo-EM density map coloured by local resolution values. b, Angular distributions of the final N-terminal reconstruction. c, Fourier shell correlations (FSEC) curves for the N-terminal map and model. d, Full-length cryo-EM density map coloured by local resolution values. e, Angular distributions of the final full-length reconstruction. f, Fourier shell correlations (FSEC) curves for the full-length map and model. g, Fragments of cryo-EM density map and atomic model of LPD-3, Spigot, and phospholipid molecules in the tunnel. The cryo-EM maps are shown as mesh.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Cryo-EM density map of the full-length LPD-3 complex.

a, Cryo-EM density map of the full-length LPD-3 complex, shown parallel to the membrane. b, Clipped view of the density map, showing that an internal cavity is observed along the entire length of the map. c, A model of the N-terminal LPD-3 complex is fit within the full-length density map. The full-length density map is shown in opaque grey and the model is coloured as in Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Alphafold-predicted models of LPD-3 complex subunits.

a, The Alphafold-predicted model of LPD-3. β-strands are coloured gold, α-helices are pink, and coils are green. b, The Alphafold-predicted structure of LPD-3, coloured as in (a), is superposed on the experimental model of LPD-3 (teal), revealing a high degree of structural similarity. The structures exhibit an overall α-carbon RMSD of 5.6 Å. c, The superposed structures of the LPD-3 experimental model (teal) and the Alphafold-predicted structure (gold) are shown in licorice representation. The Cγ atoms of the residues that form the ionizable track are shown as spheres, highlighting the conserved orientation of these residues in the experimental and predicted structures. d, The Alphafold-predicted model of Spigot, coloured as in (a). e, The Alphafold-predicted model of LTAP2, coloured as in (a).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Lipid organization within the tunnel and the ionizable track.

a, Cross sections of the tunnel are shown for the indicated RBG domains to highlight the changes in tunnel width and lipid organization. The protein is coloured according to secondary structure element: α-helices are pink, loops are white, and β-strands are teal. Lipids are shown as grey sticks. b, 90° rotated view of the indicated RBG domains shows the organization of lipids, as well as the locations of ionizable residues within the LPD-3 tunnel. Basic resides are shown as blue spheres and acidic residues are shown as red spheres. Other structural elements are coloured as in (a).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Knockdown of spgt-1 and LTAP2.

a, Representative confocal fluorescence images showing the actin reporter act 5p::act-5::GFP in wildtype C. elegans and C. elegans that were treated with RNAi targeting lpd-3, spgt-1, or LTAP2. Corresponding brightfield images are shown below each GFP fluorescence image. The apical intestinal membrane is indicated with an arrow. N = 24 worms were imaged for each condition. Scale bar is 20 μm. For the sequences of each RNAi construct, see Supplementary Table 1. b, Percentages of animals that reached developmental L4 stage at indicated hours post egg preparation in wild type (WT) worms, ΔLTAP2 worms, or mVenus::lpd3 worms. Values are means +/− S.D. c, Percentages of L4 stage animals that survived cold exposure (4 °C for 20 h) in wild type (WT) worms, ΔLTAP2 worms, or mVenus::lpd3 worms. Values are means +/− S.D. d, Percentages of L4 stage animals that survived freeze exposure (−20 °C for 45 min) in wild type (WT) worms, ΔLTAP2 worms, or mVenus::lpd3 worms. Values are means +/− S.D. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 (two-sided unpaired t-test, N = 12 biological replicates for all experiments in (b), (c), and (d)). e, Knockdown of endogenous C1orf43 or BLTP1 with siRNA leads to ER-PM contact site collapse as visualized by GFP::MAPPER. Cells are outlined with white dashed lines. Scale bar is 20 μm. N = 15 cells were imaged for each condition. f, Representative confocal microscopy image of a HeLa cell expressing GFP::MAPPER to mark ER-PM contact sites. Scale bar = 10 μm. g, Representative confocal microscopy images of a HeLa cell co-expressing GFP::MAPPER and C1orf43::FLAG, showing robust colocalization. Mislocalization of GFP::MAPPER, a potential indicator of cellular stress, is evident when the leftmost image is compared to (f). Cells are outlined with white dashed lines. Scale bar = 10 μm. h, Quantitation of the co-localization between GFP::MAPPER and C1orf43::FLAG. N = 15 biological replicates for both samples. Data are presented as mean values +/− S.E.M.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, Y., Lehmann, K.S., Long, H. et al. Structural basis of lipid transfer by a bridge-like lipid-transfer protein. Nature 642, 242–249 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08918-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08918-y

This article is cited by

-

Structural clues about bridge-mediated lipid transfer

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2025)

-

TMEM170 proteins are lipid scramblases associated with bridge-type lipid transporters BLTP1/Csf1

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2025)

-

BLTP3A is associated with membranes of the late endocytic pathway and is an effector of CASM

The EMBO Journal (2025)