Abstract

Most people in the USA manage their health by taking at least one prescription drug, and drugs classified as non-antibiotics can adversely affect the gut microbiome and disrupt intestinal homeostasis1,2. Here we identify medications that are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal infections across a population cohort of more than one million individuals monitored over 15 years. Notably, the cardiac glycoside digoxin and other drugs identified in this epidemiological study are sufficient to alter the composition of the microbiome and the risk of infection with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Tm) in mice. The effect of digoxin treatment on S. Tm infection is transmissible through the microbiome, and characterization of this interaction highlights a digoxin-responsive β-defensin that alters the microbiome composition and consequent immune surveillance of the invading pathogen. Combining epidemiological and experimental approaches thus provides an opportunity to uncover drug–host–microbiome–pathogen interactions that increase the risk of infections in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Disruption of the gut microbiome can have a wide range of consequences depending on the individual and the environment, including inflammatory bowel disease, autoinflammatory disease, colon cancer and gastrointestinal (GI) infections3,4,5,6. However, these diseases are individually rare, and the specific triggers and resulting microbiome changes that alter risk in susceptible individuals remain mostly unknown. Large-scale, prospective epidemiological studies (of tens to hundreds of thousands of individuals) are a crucial strategy to identify risk factors for rare pathologies in human populations, but this approach is challenging in the context of the gut microbiome because available cohorts that are sufficiently powered to include rare events do not incorporate microbiome data captured before and after the onset of disease.

One of the most widespread consequences of microbiome disruption is a loss of colonization resistance in the GI tract, in which the gut microbiome loses its ability to work in concert with the host immune system to prevent the expansion of pathogens in the gut. Notably, the use of prescription medications is commonly associated with GI side effects, including infections6,7,8. These side effects contribute to drug-related hospitalizations and can limit drug tolerance9. Although both oral and non-oral medical drugs can alter microbiome composition and gut microorganisms can metabolize medical drugs2,10,11,12,13, potential connections between non-antibiotic prescription drug use, microbiome disruption and infection risk are mainly unknown. Given that most people in the USA maintain their health by taking one or more prescription medications, and that diarrhoeal diseases kill more than one million people globally each year1,14,15,16, such interactions have widespread implications.

Although microbiome data are not directly available in large-scale, longitudinal epidemiological datasets, we reasoned that clinical diagnosis codes reporting GI infection could serve as an indirect indicator of microbiome disruption in a large human population. In this report, we analysed prescription drug use and clinical diagnosis codes from more than one million individuals over 15 years to identify drugs associated with an increased risk of GI infection. We found that many of these drugs, including the cardiac glycoside digoxin, alter gut microbiome composition and colonization resistance in a mouse model of infection with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Tm). We show that digoxin induces the retinoic-acid-related orphan receptor (ROR)γt-dependent expression of a previously uncharacterized family of enteric β-defensins, which, in turn, selectively decreases commensal microorganisms that promote immune surveillance against enteropathogens. Integrating epidemiological and experimental approaches therefore constitutes a strategy to identify triggers of microbiome disruption in human populations that alter the risk for pathologies recorded in clinical diagnosis codes.

Drug–infection links in a cohort of one million people

To identify drugs associated with increased infection risk in humans, we examined medical services, hospitalization and pharmacy claims data in a dynamic cohort of more than one million anonymized individuals, spanning 15 years. We designed a case–crossover study to perform this analysis, which allowed us to use each case as their own control, effectively adjusting for various known and unknown individual characteristics that could influence the underlying risk of GI infection17 (Fig. 1a). To this end, we identified the first recorded infectious GI event for each individual within the 15-year time period (Supplementary Table 1). Next, we established a case window of around 60 days immediately preceding the infectious GI event and a control window of around 60 days immediately before the case window, and assessed exposure to prescription drugs in both case and control windows (Extended Data Fig. 1a; see Methods for details). Using conditional logistic regression, we identified drug classes that had higher odds of having been dispensed in case windows than in control windows, indicating an association between the drug classes and the risk of GI infection. Because the relationship between drug exposure and microbiome disruption is expected to vary between drugs, we assumed that recency would be important in establishing potential associations. We used a 60-day window to allow for some degree of medication non-adherence and possible lagged effects of exposure. A sensitivity analysis found similar associations when a shorter window of 30 days was used.

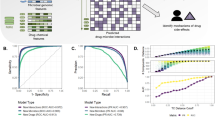

a, Design of a case–crossover epidemiological study to identify associations between prescription medications and infectious GI events across more than one million individuals. Case and control windows are defined relative to infectious GI events; for each drug, an odds ratio is calculated as the number of individuals (N) taking the drug in case periods relative to control periods. b, Epidemiological study results. Twenty-one drugs (with names listed) were identified for further study on the basis of the number of patients with drug dispensations within each class, odds ratio (OR) > 1.5 and P < 0.05. Letters (a–ba) indicate drug classes, and numbers (1–231) indicate individual drugs (Supplementary Table 2). Multivariate analysis was performed for the selected 21 drugs to adjust for potential confounders (shaded area: antimicrobial agents, immunosuppressants and antidiarrhoeals) of increased infection risk (Supplementary Table 4). c, Experimental design to study colonization resistance in mice. d, Drug-dependent differences in microbiome composition (beta diversity) measured using principal coordinate analysis on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity before and after drug treatment (left) and between drug- and control-treated mice in the same cohort at day 0 (D0) (right). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was used to calculate the amount of variation. The effect size (R2) explains the magnitude of dissimilarities between groups. Drug and vehicle names are coloured by mouse cohort. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. e, Several drugs identified in the epidemiological screen affect the S. Tm ΔinvA faecal pathogen burden in C57BL/6NTac mice (data at 12 h after infection). Statistical significance was calculated using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (n = 5 mice per drug group; n = 25 mice for vehicle group). In the box plots, the centre line is the median, the top and bottom hinges extend from the 25th to the 75th percentiles and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. CFUs, colony-forming units.

This analysis identified several expected drug classes, such as antibacterials, immunosuppressants and antidiarrhoeals, suggesting that the case–crossover strategy can successfully identify drug classes that increase the risk of GI infections (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Notably, this approach also highlighted specific non-antibiotic drug classes that increase GI infection disease risk to a similar or greater extent to that observed with the expected drug classes (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2). Next, we performed an unbiased analysis of individual drugs from both significant and non-significant drug classes and identified several drugs that were individually associated with increased infection risk. We selected medications that met specific criteria within each class (prescription number > 100, odds ratio > 1.5 and P value < 0.05), and identified 21 candidate drugs for further studies in mice (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). P values after adjustment for potential confounders (for example, concurrent use of antibiotics, antidiarrhoeals and immunosuppressants) are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Validation in mice

We next examined the effects of the 21 drugs identified in the epidemiological study on microbiome composition and infection risk in mice challenged with the model enteropathogen S. Tm. Colonization resistance is a crucial factor in determining pathogen infection in this model, and most studies rely on streptomycin treatment to disrupt the microbiome before infection18. We administered each of the 21 drugs (Supplementary Table 3), plus vehicle controls in each mouse cohort, twice daily to separate groups of conventional (CV) C57BL/6NTac mice (Taconic Biosciences) for two days with faecal sampling for 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing before treatment initiation and 12 h after the final dose. Wild-type (WT) S. Tm contains two type III secretion systems (T3SS): T3SS-1 mediates invasion of non-phagocytic cells and induces widespread gut inflammation, whereas T3SS-2 enables systemic spread and survival within the host19. Because inflammation further disrupts the microbiome, we performed the initial drug screen using an S. Tm ΔinvA strain, which lacks an integral structural component of T3SS-1 and is attenuated for colitis but encodes a functional T3SS-2 (refs. 19,20). After a 12-h washout period following the final drug dose, we infected each mouse with S. Tm ΔinvA and monitored infection over time (Fig. 1c). To quantify the effect of drug treatment on the gut microbiome, we evaluated beta diversity within groups before and after drug treatment and between drug- and control-treated groups from the same mouse cohort. Several drugs induced significant compositional changes in the faecal microbiome in at least one of these comparisons (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1c); digoxin and donepezil significantly altered microbiome composition in both comparisons. In addition, four drugs (digoxin, clonazepam, pantoprazole and quetiapine) significantly increased the pathogen burden in mice 12 h after infection (Fig. 1e). These drugs did not exhibit widespread antibiotic activity when tested on representative human gut bacterial isolates (Extended Data Fig. 1d).

Digoxin disrupts colonization resistance

Because digoxin significantly altered the composition of the microbiome and the risk of S. Tm infection in mice, and its interaction with the microbiome is well known21,22, we selected this drug for further study. Independent replication of S. Tm ΔinvA infection in digoxin-pretreated mice confirmed the significant increase in pathogen burden in faecal samples collected 12 hours, 2 days and 4 days after infection, as well as in the GI contents and extraintestinal tissues 4 days after infection (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2a–g). Consistent with this increased pathogen burden, digoxin-pretreated mice exhibited significantly increased mortality, compared with control mice that were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before S. Tm ΔinvA infection (Fig. 2b). Digoxin pretreatment had no effect on bacterial loads in the liver and spleen of mice that were infected with S. Tm ∆invA intraperitoneally; this indicates that the increase in mortality results from the higher pathogen burden in the gut and subsequent dissemination, and suggests that digoxin has a key role in altering the gut microenvironment to cause increased pathogenesis (Extended Data Fig. 2h–i).

a,b, C57BL/6NTac mice were orally gavaged with PBS (in 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) or digoxin (5 mg kg−1) and infected with S. Tm ΔinvA as in Fig. 1c. a, Faecal pathogen burden in PBS-pretreated (n = 11) or digoxin-pretreated (n = 13) mice at 12 h after infection. b, Mortality of PBS-pretreated or digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6NTac mice after S. Tm ΔinvA infection or mock infection. c, Faecal pathogen burden in PBS-pretreated (n = 22) or digoxin-pretreated (n = 23) C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice 12 h after infection with WT S. Tm. d, Survival of PBS-pretreated or digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice after infection with WT S. Tm. e,f, Effect of digoxin on infection in C57BL/6J mice. Faecal pathogen burden (n = 5 per group) (e) and mortality (f) in non-cohoused, PBS-treated or digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6J mice after infection with S. Tm ΔinvA. g, Effects of PBS pretreatment or digoxin pretreatment on S. Tm infection in C57BL/6J mice that were cohoused with C57BL/6NTac mice for 14 days. Mice were separated before PBS or drug administration and infection. h, Schematic of gut microbiome transplantation experiments. i,j, Effects of transplantation of the GI contents from PBS-pretreated or digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6NTac donor mice on S. Tm faecal pathogen burden at 4 dpi (PBS n = 9, digoxin n = 8) (i) and mortality (j) in ex-GF recipient mice colonized with either microbiome before infection. In a,c,e,i, bars represent median values, and dotted lines represent the limit of detection. Two-sided Mann–Whitney test was used for comparison. In b,d,f,g,j, P values were calculated using the Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test. NS, not significant.

C57BL/6NTac mice succumb rapidly to infection by WT S. Tm because they have a nonfunctional allele of Nramp1 (also known as Slc11a1), a gene that is essential for the bactericidal activity of macrophages; C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice exhibit increased resistance to WT S. Tm23. Pretreating C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice with digoxin before infection with WT S. Tm increased pathogen burden and mortality in these mice, compared with control mice that were treated with PBS before WT S. Tm infection (Fig. 2c,d and Extended Data Fig. 2j–k). To examine the effect of digoxin on other pathogens, we infected digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6NTac mice with Citrobacter rodentium, an attaching and effacing pathogen that is commonly used as a mouse surrogate for human pathogens such as enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli and enteropathogenic E. coli, or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE), a human pathogen associated with nosocomial infection. Notably, pretreatment with digoxin significantly increased the C. rodentium burden in the faeces (measured at the peak of infection; 10 days post-infection (dpi)), and also increased the levels of C. rodentium attached to the intestinal epithelium (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Similarly, mice pretreated with digoxin had an increased VRE burden in the faeces as well as in the GI contents (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Together, these results suggest that digoxin pretreatment is associated with an increased risk of infection in humans, independent of the concurrent use of other drugs, and is sufficient to increase infection risk in several mouse models of infection.

Digoxin can alter the activity of RORγt (encoded by the Rorc gene)24,25. RORγt is essential for the differentiation of naive T cells into proinflammatory T helper 17 (TH17) cells that produce the cytokines interleukin-17 (IL-17) and interleukin-22 (IL-22)24,25; other cell types (for example, group 3 innate lymphoid cells; ILC3) also produce these cytokines in a RORγt-dependent manner26. These cytokines act on epithelial cells to upregulate the expression of antimicrobial lectins such as Reg3g and Reg3b, and induce the expression of chemokines that promote the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the mucosal surface27,28,29. This orchestrated innate immune response contributes substantially to the establishment of a gut barrier, which is crucial for sustaining gut–immune homeostasis and conferring protection against enteric pathogens, and the presence of these factors in the ileum is implicated in resistance to S. Tm colonization27,30. Notably, expression of IL-17- and IL- 22-dependent antimicrobial lectins such as Reg3b and Reg3g was downregulated in digoxin-pretreated mice in the ileal tissue specifically, but not in the caecum and colon (Extended Data Fig. 3e–g).

We next assessed whether the direct effect of digoxin on the host is likely to explain the differences in susceptibility to infection outcome irrespective of the effect of digoxin on the microbiome. To this end, we first determined whether other digoxin treatment regimens altered the risk of infection. We assessed S. Tm ΔinvA infection in C57BL/6NTac mice that were treated with a single dose of digoxin (2 h before infection) or given an extended treatment regimen (twice-daily treatment for 7 days, followed by a 12-h washout before infection) (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Unlike the two-day treatment group, neither of these treatment strategies altered the infection outcome, relative to control mice that were treated with PBS before infection (Extended Data Fig. 4b–e). Consistent with this result, proinflammatory S. Tm resistance genes that were significantly downregulated after two days of digoxin treatment returned to baseline levels after seven days of drug administration (Extended Data Fig. 4f). These distinct phenotypes, depending on the timing of digoxin treatment, suggest that the direct effect of digoxin on the host is not sufficient to explain the increased S. Tm susceptibility.

Because digoxin treatment alters microbiome composition (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1c), we next examined whether mice with different microbiomes exhibit similar digoxin responses. Although both C57BL/6NTac mice and C57BL/6J mice exhibited a slight reduction in weight after digoxin treatment, pretreatment with the drug did not cause increased pathogen burden or altered mortality in C57BL/6J mice infected with S. Tm ∆invA (Fig. 2e,f and Extended Data Fig. 4g). Cohousing these mice with C57BL/6NTac mice for two weeks to allow for microbiome exchange altered this phenotype: C57BL/6J mice cohoused with C57BL/6NTac mice were significantly more susceptible to infection after digoxin pretreatment, compared with cohoused controls that were not treated with digoxin before infection (Fig. 2f,g). Despite this increased mortality, the pathogen burden was similar at 3 dpi, potentially because of the high dose of S. Tm that was used in this experiment (Extended Data Fig. 4h).

To determine whether the effect of digoxin on pathogen susceptibility is transmissible through the microbiome, we next treated C57BL/6NTac donor mice with digoxin or PBS for 2 days as above and, after a 12-h washout period, transplanted the gut contents of each donor mouse into a germ-free (GF) recipient mouse. Seven days after microbiome transplantation, recipient mice were euthanized (to measure proinflammatory markers) or infected with S. Tm ΔinvA (Fig. 2h). Recipient mice carrying the microbiomes of digoxin-treated donor mice exhibited significantly reduced expression of proinflammatory markers before infection and increased pathogen burden, weight loss and mortality after infection, compared with recipients that were colonized with the microbiomes of PBS-treated mice (Fig. 2i,j and Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). By contrast, transplanting the gut contents from C57BL/6NTac donor mice that were treated for seven days with digoxin or PBS, or from C57BL/6J donor mice that were treated for two days with digoxin or PBS, into GF recipient mice resulted in no difference in S. Tm ΔinvA susceptibility between recipient groups (Extended Data Fig. 5c–g; as above, gut contents were collected from donor mice 12 h after the last dose of digoxin or PBS). Together, these data suggest that the direct interaction between digoxin and host cells (including any trace carryover from microbiome transplantation after the 12-h washout in donor mice and 7 days in recipient mice) is not sufficient to increase susceptibility to S. Tm infection.

Digoxin decreases SFB abundance

Because the effect of digoxin on infection was transmissible through the microbiome, we next evaluated digoxin-mediated changes in the microbiome in C57BL/6NTac and C57BL/6J mice. Digoxin treatment significantly altered the composition of the gut microbiome in both C57BL/6NTac and C57BL/6J mice (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c), and its effects included a decrease in the relative abundance of several Lactobacillus taxa (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6d,e). Digoxin treatment also led to a marked depletion of ‘Candidatus savagella’ in C57BL/6NTac mice; this microorganism was absent in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6f). ‘Candidatus savagella’ is a member of the segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) group of spore-forming, Gram-positive bacteria. SFB attach to the ileal epithelium and trigger a cascade of host immune responses, including upregulation of the serum amyloid A (SAA1 and SAA2) pathway and activation of RORγt, which results in a proinflammatory gut environment that protects against invading pathogens27,31. Consistent with the 16S rRNA sequencing results, targeted quantitative PCR (qPCR) measurement of the levels of SFB in C57BL/6NTac and C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice indicated a significant reduction in faecal SFB levels after digoxin pretreatment (Fig. 3b,c). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses of ileal tissue from digoxin- and vehicle-pretreated mice showed that digoxin pretreatment almost completely eliminated SFB from the ileal epithelium (Fig. 3d). Mice pretreated with 0.5 mg kg−1 digoxin also showed a significant reduction in SFB as measured by qPCR and SEM, indicating that two days of digoxin treatment alters the ability of SFB to attach to the ileal epithelium or colonize the gut across the range of digoxin doses used in the literature24,25 (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 6g). Notably, the other drugs selected from the epidemiological screen do not affect the abundance of SFB in mice, suggesting that additional mechanisms contribute to the drug-mediated loss of colonization resistance (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a, Volcano plot showing differentially abundant taxa in the faecal contents of PBS-pretreated and digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6NTac mice. b,c, SFB abundance in PBS-pretreated or digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6NTac (n = 5 per group) (b) and C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ (n = 8 per group) (c) mice relative to total bacteria, as measured by qPCR. d, SEM of the terminal ileum of C57BL/6NTac mice pretreated with PBS or digoxin. Representative images are shown from two independent experiments. Scale bars, 40 μm. e, Representative flow-cytometry plots showing ileal CD4+IL-17A+ T cells (top), ileal neutrophils (middle) and ileal Ly-6Chi monocytes and macrophages (bottom) from PBS-pretreated or digoxin-pretreated mice. CD4+ T cells were gated as B220−NK1.1−TCRβ+CD4+CD8−. Neutrophils were gated as B220−NK1.1−TCRβ−CD11b+Ly-6G+. Monocytes and macrophages were gated as B220−NK1.1−TCRβ−CD11b+Ly-6G−Ly-6Chi. f–h, Frequency of IL-17A+CD4+ T cells after ex vivo stimulation with PMA and ionomycin (f), neutrophils (g) or Ly-6Chi monocytes and macrophages (h) from the ileal lamina propria of PBS-pretreated or digoxin-pretreated mice (n = 5 mice per group). i, C57BL/6J mice cohoused with C57BL/6NTac mice acquire SFB, which is reduced after treatment with digoxin (Dig). Mice were separated before PBS or drug administration (n = 5 per group). Data are mean ± s.e.m. j, Relative abundance of SFB in ex-GF recipient mice after transplantation of the GI contents from PBS-pretreated or digoxin-pretreated C57BL/6NTac donor mice (n = 5 per group). Data are geometric mean values; error bars are geometric s.d. k,l, SFB colonization is sufficient to alter the response of C57BL/6J mice to digoxin. SFB colonization was done on day (−14) relative to infection, and drugs were administered for two days before infection as in Fig. 1c. k, Relative abundance of SFB after PBS (n = 8) or digoxin (n = 6) pretreatment. l, Mortality after S. Tm ΔinvA infection. P value calculated using the Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test. In b,c,f–h,i–k, two-sided Mann–Whitney test was used for comparison.

Four lines of evidence further suggest that the effect of digoxin on immunomodulatory microorganisms such as SFB is a key step in determining how the drug affects susceptibility to pathogens. First, SFB-depleted mice exhibited a significant decrease in the proportion and total numbers of IL-17A-producing CD4 T cells, neutrophils and Ly-6Chi monocytes and macrophages in the small intestine lamina propria (Fig. 3e–h and Supplementary Fig. 2a–e). Consistent with this, the expression of Il17a and of marker genes of neutrophils and monocytes was significantly downregulated in digoxin-pretreated mice (Extended Data Fig. 6h–n). Second, treating SFB-negative C57BL/6J mice with digoxin had no effect on S. Tm infection; C57BL/6J mice cohoused with C57BL/6NTac mice became colonized with SFB and treating these mice with digoxin after cohousing decreased their levels of SFB and increased S. Tm pathogenesis, relative to PBS-treated controls (Figs. 2e–g and 3i). Third, SFB levels were significantly reduced in ex-GF recipient mice that were engrafted for seven days (to allow for microbiome equilibration) with the microbiomes of digoxin-treated C57BL/6NTac donor mice, compared with recipients engrafted with the microbiomes of PBS-treated donors (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 7a–c). Finally, we directly colonized C57BL/6J mice with faecal material from SFB-monoassociated gnotobiotic mice; these mice became robustly colonized with SFB and treatment with digoxin resulted in a significant depletion in the SFB population (Fig. 3k) and increased pathogen burden and infection susceptibility (Fig. 3l and Extended Data Fig. 7d). In line with the observation that the effect of digoxin on infection susceptibility and proinflammatory marker genes is transient (Extended Data Fig. 4b–f), SFB levels recovered in mice that were treated with digoxin for five days or more (Extended Data Fig. 7e). A brief drug discontinuation period is sufficient to render the system digoxin-sensitive again (Extended Data Fig. 7f). Finally, we treated C57BL/6NTac mice with vancomycin to ascertain whether treatment with antibiotics that reduce the levels of SFB is sufficient to recapitulate the effect of digoxin on SFB-dependent proinflammatory marker genes. Indeed, oral vancomycin reduced the levels of SFB and the expression of these genes (Extended Data Fig. 7g,h). Together, these results suggest that treatments that reduce the levels of SFB for two days are sufficient to alter gut–immune homeostasis.

Digoxin-induced BD-39 controls SFB levels

Because digoxin binds to the master transcription factor RORγt24, we next examined whether the digoxin-dependent decrease in SFB is RORγt dependent. Pretreating SFB-colonized Rorc−/− mice with digoxin did not result in reduced SFB levels or increased susceptibility to infection (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8a,b), suggesting that, first, digoxin does not directly kill SFB, and second, digoxin reduces the levels of SFB in a RORγt-dependent manner. Although RORγt is expressed in both TH17 and ILC3 cells, mice specifically lacking ILC3 cells32 exhibit a reduction in SFB in response to digoxin, as observed in WT mice, whereas mice lacking both TH17 and ILC3 cells are insensitive (Extended Data Fig. 8c). We also examined Rag1−/− mice, which lack mature T and B cells: treating SFB-monocolonized Rag1−/− mice with digoxin had no effect on SFB abundance in these mice, whereas SFB-monocolonized WT control mice showed a significant decrease in SFB abundance after treatment with digoxin (Extended Data Fig. 8d). Together, these observations suggest that digoxin controls SFB levels in a TH17-dependent manner.

a, Effects of PBS or digoxin pretreatment on SFB levels in SFB-colonized Rorc−/− mice (n = 8 per group) and their WT littermate controls (n = 7 per group). b,c, Relative expression of selected genes encoding AMPs in ileal tissue of C57BL/6NTac mice with or without digoxin pretreatment (exact n and P values are provided in the Source Data) (b) and RNA-seq (c). Two-tailed unpaired t-test. d–f, Expression of Defb39 in ileal tissue of SFB-colonized Rorc−/− mice (n = 4 per group) (d), GF mice (n = 5 per group) (e) and SFB-monocolonized ex-GF mice (f) after PBS (n = 4) or digoxin (n = 6) pretreatment. g, Absolute SFB abundance in the ileum contents of ex-GF mice monocolonized with SFB and treated with PBS (n = 5) or digoxin (n = 6). h, Expression of SFB-responsive (Saa1 and Reg3g) genes in ileal tissue of ex-GF mice monocolonized with SFB and treated with PBS (n = 4) or digoxin (n = 6). i, SFB abundance in faecal samples from Vil-Defb39 transgenic mice and WT controls (n = 3 per group). j, Schematic for measuring the antimicrobial activity of purified BD-39 against SFB. k, Absolute SFB abundance over time in ex-GF mice (n = 3 per group). Two-sample Welch t-test was used to compare the two groups. In b,d–f,h, fold change is measured relative to the mouse housekeeping gene, Gapdh. In a,d–i, a two-sided Mann–Whitney test was used to compare two groups. In a, multiple comparisons were made using the Bonferroni–Dunn method. Bars represent median values in a,g and geometric mean values in d–f,h. Data in i,k are s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Because antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) such as REG3γ and α-defensins are linked with reduced SFB abundance in the gut33,34, we measured the expression of a panel of AMPs in the ileal tissue of digoxin- and PBS-pretreated C57BL/6NTac mice. Digoxin pretreatment in general had no effect or resulted in downregulation of most of the measured AMPs; however, drug treatment resulted in a significant upregulation of Defb39, the gene that encodes β-defensin 39 (BD-39) (Fig. 4b). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of ileal tissue (from a separate cohort of digoxin- and PBS-pretreated C57BL/6NTac mice) confirmed the digoxin-dependent upregulation of Defb39 that was observed in the targeted gene-expression study, and further identified a second member of this β-defensin family (BD-37) as potentially upregulated in digoxin-pretreated compared with PBS-treated mice (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 8e). Consistent with the digoxin-dependent reduction in SFB levels and previous targeted gene-expression analyses, these RNA-seq measurements highlighted the digoxin-induced downregulation of SFB-dependent genes27 (Saa1 and Saa2), as well as key proinflammatory factors involved in the control of S. Tm infection (Il17a, Il22, Reg3b, Reg3g, Cxcl1, Cxcl2 and Ccl2; Extended Data Figs. 3e, 6h–n and 8e,f). The digoxin-dependent induction of Defb39 was specific to the ileum (Extended Data Fig. 8g), which is the primary site of SFB attachment; digoxin-dependent repression of Reg3b and Reg3g in SFB-positive mice was also specific to the ileum (Extended Data Fig. 3e–g).

Notably, pretreating SFB-colonized Rorc−/− mice with digoxin did not alter the expression of Defb39 in these mice, and administering WT mice with digoxin for an extended (seven-day) interval returned Defb39 expression to untreated levels (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 8h). In addition, GF mice, which lack TH17 cells in the small intestine lamina propia27, did not overexpress Defb39 in the ileum after digoxin treatment (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, treating SFB-monoassociated GF mice with digoxin resulted in significantly increased expression of Defb39, reduced SFB abundance and decreased expression of canonical SFB-regulated genes (Saa1 and Reg3g) (Fig. 4f–h). Together, these results suggest that other members of the microbiota are not necessary for digoxin-dependent Defb39 upregulation or SFB reduction. To determine whether Defb39 upregulation is sufficient to modulate the levels of SFB, we generated transgenic mice that constitutively express Defb39 under the control of the intestinal epithelium-specific villin (encoded by Vil1) promoter (referred to as Vil-Defb39). These mice overexpress Defb39 throughout the length of the gut (Extended Data Fig. 9a) and exhibit robust changes in the microbiome, including a significant decrease in Lactobacillus (Extended Data Fig. 9b–d). Notably, transgenic expression of Vil-Defb39 significantly reduced the levels of SFB, compared with WT C57BL/6NTac controls; SFB levels in Vil-Defb39 mice were similar to those in digoxin-pretreated WT mice (Figs. 3b and 4i and Extended Data Fig. 9e). We next purified recombinant BD-39 and assessed its activity against a panel of commensal species spanning the major gut phyla. Notably, certain species (for example, Clostridium sporogenes and S. Tm) were insensitive to BD-39, whereas others (including Lactobacilli strains) showed moderate or high levels of sensitivity (Extended Data Fig. 9f). Efflux pumps and the outer membrane barrier probably contribute to BD-39 resistance, because an E. coli ΔbamBΔtolC strain showed significantly increased sensitivity, compared with the WT strain (Extended Data Fig. 9f). To test whether BD-39 exhibits direct antimicrobial activity against SFB (which is not readily cultured in vitro), we incubated the caecal contents from SFB-monoassociated mice with purified BD-39 or control buffer under anaerobic conditions, inoculated the incubated samples into GF mice and measured SFB viability in the inoculum by quantifying SFB levels over time in recipient mice. Notably, SFB levels were significantly reduced in mice colonized with the BD-39 incubated samples, as compared to those colonized with the buffer-incubated samples, indicating that BD-39 can kill SFB directly (Fig. 4j,k). These data suggest that pretreatment with digoxin induces the expression of Defb39 in a RORγt-dependent manner and that Defb39 expression is sufficient to reduce SFB levels and alter consequent immune responses in mice.

Digoxin and infection in human-microbiome mice

Although SFB is rare in humans35, individuals exhibit extensive interpersonal variation in other TH17-inducing gut microorganisms36. In addition, human microbiomes exhibit interpersonal variation in digoxin metabolism22 (inactivation), which is mediated by the microbial enzyme Cgr2. Oral administration of the Cgr2-dependent digoxin metabolite, dihydrodigoxin, does not alter SFB levels or S. Tm infection in mice (Extended Data Fig. 10a–c). To determine whether TH17-inducing human gut microorganisms render mice susceptible to digoxin-mediated loss of colonization resistance, we rederived C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice to the GF state, colonized these mice with a defined 20-strain consortium of human gut species known to induce a TH17 response36 (Supplementary Table 6) and measured the digoxin response in these mice (this consortium does not include cgr2-positive species). Notably, digoxin pretreatment reduced the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the ileum, as observed in C57BL/6NTac (SFB-positive) mice (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 10d). To extend these results to complete human gut communities, we reasoned that a pooled human-microbiome sample would be likely to include TH17-inducing taxa. We first estimated the cgr2 gene abundance across the microbiomes of 30 human donors12 using targeted and metagenomic approaches; approximately half of the individuals lacked detectable cgr2 (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 10e). We colonized GF C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice with a pooled sample from eight cgr2-negative human donors, and measured the digoxin response in these mice. Colonizing GF Nramp1+/+ mice with these human communities resulted in robust expression of Il22 (Fig. 5d). Notably, digoxin pretreatment reduced the expression of Il22 and Il17a, increased the levels of Defb39 in the ileum and variably affected the expression of other proinflammatory marker genes (Fig. 5d–f and Extended Data Fig. 10f). In addition, digoxin treatment altered the microbiome, including depleting Lachnospiraceae and Bacteroides (Extended Data Fig. 10g). Furthermore, infection with WT S. Tm resulted in a significantly increased pathogen burden in digoxin-treated mice compared with PBS-treated controls carrying the same pooled human community (Fig. 5g). Consistent with this increased pathogen burden, digoxin-pretreated, S. Tm-infected mice exhibited increased expression of S. Tm-responsive inflammatory marker genes19,37 (Fig. 5h). Collectively, these studies suggest that the effect of digoxin pretreatment on infection risk is conserved in the context of SFB-negative human microbiomes.

a, Experimental design. A TH17-inducing defined community of human gut isolates or pooled human faecal samples were used to colonize GF C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ recipient mice. Mice were treated with PBS (n = 4) or digoxin (n = 5) as in Fig. 1c. Twelve hours after the final treatment dose, mice were euthanized or infected with WT S. Tm. b, Ileal expression of selected marker genes at day 0 in mice colonized with the TH17-inducing defined community. c, Schematic for pooling human-microbiome samples. d, Ileal expression of Il22 at day 0 in mice colonized with TH17-inducing pooled human gut microbiomes (GF n = 5, PBS n = 4, digoxin n = 4). Ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare multiple groups. e, Expression of Il17a in digoxin-pretreated (n = 4) or PBS-pretreated (n = 4) ex-GF mice. f, Expression of Defb39 in digoxin-pretreated (n = 5) or PBS-pretreated (n = 5) ex-GF mice. g,h, Ex-GF Nramp1+/+ mice pretreated with PBS (n = 5) or digoxin (n = 5) were infected with WT S. Tm. g, Pathogen burden in the faeces and in the contents of the ileum, caecum and colon at 4 dpi. h, Gene expression of S. Tm-responsive inflammatory marker genes in ileal tissue from mice colonized with pooled human communities at 4 dpi. Two-sided Mann–Whitney test was used to compare two groups in b,e–h. Bars are geometric mean values in b,d–f,h, and median in g.

Discussion

Several GI diseases are linked with the microbiome. Here we used large-scale epidemiological human data to identify prescription medications that represent risk factors for infectious GI diseases. Nearly half of the non-antibiotic medications identified in the epidemiological study altered microbiome composition, susceptibility to infection or both in mice. We focused on digoxin, which alters the risk of infection in mice by inducing the expression of β-defensins that reconfigure the gut microbiome, leading to immune reprogramming and a diminished response to pathogens (see Supplementary Discussion). In the context of a mouse gut microbiome, immune reprogramming is mediated by SFB; gnotobiotic mice colonized with IL-17a- and IL-22-inducing human communities lacking SFB exhibit similar responses, suggesting that this response is conserved across mice and humans.

BD-39, an orthologue of human BD-1, is a member of a family of β-defensins that are conserved across mammals; the human genome encodes more than 30 members of this family38. Human BD-1 is expressed in the GI tract, including the colon and ileum, and is induced in the presence of pathogens or other signals39,40. Although infection and inflammation at the mucosal surface are generally thought to be the triggers for induction of β-defensins41, our data indicate that xenobiotic compounds such as digoxin also serve as inducing signals. Notably, BD-39 expression returns to baseline levels after extended treatment with digoxin. Although the specific attenuating mechanism requires further study, induction of regulatory T cells can promote immunogenic tolerance against compounds such as food antigens42,43. In mice subjected to an extended digoxin treatment regimen, temporary discontinuation followed by resumption of digoxin treatment resensitized the mice to the effects of digoxin on BD-39 expression, SFB levels and consequent immune responses. The epidemiological study is likely to have included patients who began digoxin treatment at the end of the case window, as well as individuals who were temporarily noncompliant (missed doses), which could explain why digoxin increases infection risk in patients despite attenuation over time in mice. Notably, around 25% of patients treated with digoxin are typically noncompliant owing to underdosing44.

Whether digoxin-dependent BD-39 expression and consequent microbiome remodelling is adaptive or accidental remains unclear. Like many medications, digoxin is derived from a poisonous plant (foxglove), and several examples of microbiome-mediated responses to plant compounds are observed in nature45. Other factors, such as environmental exposures, diet and pathogen infection, can also disrupt the composition of the microbiome; epidemiological studies track each of these events in large human cohorts46,47,48,49,50. Furthermore, medical records document diverse health outcomes with potential links to microbiome disruption, including conditions such as non-infectious colitis and colon cancer, and show how the microbiome can affect drug efficacy and toxicity51,52,53,54. The combination of epidemiological and experimental approaches described here could be used to define mechanistic relationships between other causes and consequences of microbiome disruption in humans, and to identify individuals at risk, as well as therapeutic interventions.

Strengths and limitations

In this study, we examined the association between drugs and infectious GI events over 15 years across a population of more than one million people who had public insurance coverage for all medical care and prescription medications. The design of the epidemiological study was chosen for efficiency, which allowed us to model a large number of drugs. However, several important limitations should be noted, including the high frequency of chronic medications prescribed in both case and control windows and the necessity for follow-up experimental studies in mice (see Supplementary Discussion). Further studies will also be necessary to define how the associations found in this cohort extend to other populations. We also note that, although several lines of evidence highlight the role of BD-39 in mediating the effects of digoxin on colonization resistance in mice, the role of orthologous proteins in humans was not tested in this study.

Methods

Epidemiological study design and analysis

Epidemiological design and data source

To investigate therapeutic drug classes and individual drugs that might affect colonization resistance, we performed a case–crossover study in a population-based dynamic cohort. The case–crossover design was selected because it allowed us to use each case as their own control, thereby adjusting for known and unknown individual characteristics that might influence the outcome of GI infection17,55,56. The population-based dynamic cohort comprised a population-based 25% random sample of the 4.1 million residents of Montreal, Quebec, followed over a period of 15 years from 1999 to 2014. The cohort is dynamically updated each year to account for migration in and out of the area. Each member of the cohort is provided with universal health insurance for all medical and hospital care through the provincial health insurer (Regie de l’assurance maladie du Québec; RAMQ). In addition, all essential drugs are covered for residents aged 65 years or older, those receiving income security and those without drug insurance through their employer (approximately 50% of Quebec residents). For each member of the cohort, RAMQ provided the research group with all medical services received including the date and location of the service, patient and physician identification, primary diagnosis, type of visit and reimbursement provided, as well as records of all RAMQ-covered drugs dispensed through community pharmacies (date, drug, patient and pharmacy identification). These data were linked by patient identification to the provincial birth and death registry, which records the date, time and cause of death, as well as to the Ministry of Health database on all hospitalizations in the province (patient identification, dates of admission and discharge, primary and secondary discharge diagnoses, and procedures).

Definitions of case and control periods and sampling relative to drug exposure

Within this cohort of 1,434,375 individuals, we identified all individuals who had a physician claim or hospital admission with the primary diagnosis of a GI problem suspected to be of infectious origin (events). The code set of diagnostic codes (indicated by relevant International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision (ICD-9 and ICD-10) codes) was developed based on previously validated code sets57,58 and included ICD-9 codes (001x, 002x, 003x, 004x, 005x, 0060, 0061, 0062, 0069, 007x, 008x and 009x) and ICD-10 codes (A00x, A01x, A02x, A03x, A04x, A05x, A060, A061, A062, A069, A07x, A08x and A09). If an individual had multiple visits for an infectious GI problem, we selected the first visit. Prescription drug use in the 60 days (around 2 months) before the visit for an infectious GI problem was assessed (case period). To avoid misclassification of the timing of drug exposure (that is, the drug was prescribed to treat the GI problem), we excluded drugs that were prescribed in the three-day period directly before the GI-related visit. For each patient, we selected a control date that was around two months before the first GI-related visit. Drug use was assessed in the two months before the control date, excluding the same three-day gap period before the control date to assess drug use (Extended Data Fig. 1a). In a sensitivity analysis, we used a shorter window of 30 days for each of the case and control periods.

Measurement of prescription drug use

In each two-month case and control period, we created a drug-by-day matrix using the date of dispensing and the duration of supply for each prescription filled by a patient. Drugs were classified by ingredient and therapeutic class using the American Hospital Formulary System (AHFS, see https://ahfsdruginformation.com/).

Analysis and visualization of epidemiological data

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Conditional logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between GI infection risk with each therapeutic class and drugs frequently prescribed within each therapeutic class. Several drug classes were considered expected associations (including antimicrobial agents; immunosuppressive agents; antidiarrhoeal agents; analgesics and antipyretics; antiemetics; and cathartics and laxatives) and were ruled out of further investigations. On the basis of the selected inclusion criteria (>100 dispensations, odds ratio > 1.5 and P < 0.05), a subset of drugs was identified for further investigation in mouse models (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2). Drugs that were not well-tolerated in mice (for example, risperidone) were excluded, resulting in a final list of 21 drugs. Epidemiological data were visualized using a complex heat map59 to illustrate the criteria used for drug selection (Fig. 1b).

For the final list of 21 drugs that were selected for further investigation in mouse models, we assessed whether the concurrent use of antibiotics, immunosuppressants and/or antidiarrhoeals modified the association by including binary indicators for use (yes/no) in multivariate models (Supplementary Table 4).

Chemicals and primers

Drugs for animal studies were purchased individually, and drug dosages were determined according to previous studies (Supplementary Table 3). All of the primers used in the study are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Microbiological culture and growth measurements

Bacterial strains

All bacterial strains and isolates used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Aerobic growth conditions

Routine aerobic culturing was performed in Luria Bertani (LB) broth using shaking conditions (220 rpm) at 37 °C for 16 h. Stocks were prepared from 16-h cultures using autoclaved glycerol (20% final concentration) and stored at −80 °C.

Anaerobic growth conditions

All anaerobic microbiology steps were performed in a flexible anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products) containing 20% CO2, 10% H2 and 70% N2, using pre-reduced media and materials. Routine anaerobic culturing was done using liquid mega medium60 or Brucella blood agar plates. Stocks were prepared under anaerobic conditions from 16-h cultures using autoclaved glycerol (20% final concentration) and stored in single-use aliquot vials at −80 °C.

In vitro growth assays

To measure the effects of medical drugs on the growth of representative gut microbial species, growth measurements were made at three relevant drug concentrations (20 µM, 40 µM and 80 µM), as described previously10. To this end, 384-well plates were freshly prepared with each of the 21 identified drugs (Fig. 1b) at each concentration in modified Gifu anaerobic medium (HyServe) and stored in the anaerobic chamber for 24 h before bacterial inoculation. Twelve representative human gut isolates, S. Tm, E. coli and E. coli ∆bamB∆tolC61 (Supplementary Table 6) were cultured for 16 h and inoculated in quadruplicate into the 384-well plate at an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600 nm) of 0.025. Plates were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 24 h, and the OD600 nm was recorded every 15 min after mixing for 1 min prior to measurement. Medium controls were used as blanks. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to evaluate bacterial growth under different drug concentrations, which were compared with the AUC for the corresponding vehicle concentrations (DMSO controls). Double-sided Mann–Whitney U tests were performed to test the significance of AUC differences, and P values were corrected by the Benjamini–Hochberg method, with P < 0.05 after multiple-hypothesis testing considered significant. AUC differences were converted into a heat map using the R package pheatmap62, and clustering was performed on the basis of the bacterial growth AUC.

Mouse experiments

Conventional and gnotobiotic husbandry

All mice experiments were performed using protocols approved by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and all mice were kept in a 12-h light–dark cycle. For housing conditions, the temperature was maintained at between 20 °C and 26 °C and the humidity at between 30% and 70%. Six-to-eight-week-old CV mice were used in these studies unless stated otherwise. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but sample sizes were similar to those reported in previous studies of colonization resistance63,64. Female mice were used for colonization resistance screening and cohousing experiments. Both sexes were used for all other experiments. CV mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions with unlimited access to water and food (Teklad Global 16% protein rodent diet, Envigo). GF mice were housed in gnotobiotic isocages (Sentry sealed positive pressure (SPP) isolation cage system; Allentown). In experiments using gnotobiotic mice carrying faecal microbiome transplants from individual donor mice or pooled human faecal samples, gnotobiotic recipient mice were individually housed in flexible plastic gnotobiotic isolators. Gnotobiotic mice were fed a standard, autoclaved mouse chow (5K67 LabDiet, Purina) ad libitum and provided with autoclaved water for the duration of the experiment. GF status was routinely monitored by 16S rRNA-targeted PCR of faecal DNA and culturing of faecal samples under aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

Investigation of candidate drugs in mice

Groups of six-to-eight-week old female C57BL/6NTac mice (Taconic Biosciences) were treated with each of the 21 candidate drugs identified in the epidemiological analysis (Fig. 1b; n = 5 per group) in cohorts of 4 or 5 drugs per cohort. All mice within a cohort were obtained concurrently, and a vehicle control group was included in each cohort. All drugs were dissolved in 90% PBS, 5% DMSO and 5% Tween 80 to create consistent treatment conditions between the groups. Drug dosage was determined according to the literature (Supplementary Table 3), and drugs that were not completely dissolved were administered as a slurry; each drug was prepared fresh before gavage. Mice were orally gavaged with individual drugs twice daily for two days (four doses in total). The first drug dose was administered in the evening (Zeitgeber time (ZT)12), with the three subsequent doses at 12-h intervals. Faecal samples were collected for microbiome assessment immediately before the first drug treatment (D(−2)) and 12 h after the final dose (D0; also ZT12). For infections, approximately 108 colony-forming units (CFUs) of S. Tm ∆invA (ref. 20), prepared as described below, were used for infection by oral gavage at the D0 time point (ZT12, 12 h after the final drug dose). S. Tm ∆invA CFUs were enumerated from faeces 12 hours, 1 day, 2 days and 4 days after infection.

Pathogen infection

WT65 and ΔinvA (SB1901)20 genotypes of S. Tm strain SL1344 were grown in LB broth overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. After 16 h of growth, bacteria were washed twice and resuspended in autoclaved PBS. Mice were infected with around 108 CFUs by oral gavage unless otherwise stated, and were weighed at the same time daily before and after infection. For S. Tm infections, mice were euthanized at 4 dpi or monitored for survival as described below. For intraperitoneal infections, mice were infected with around 105 CFUs, and the liver and spleen were collected at 1 dpi. For quantification of faecal S. Tm CFUs, faeces were weighed, homogenized by vortexing in 1 ml of sterile PBS, serially diluted in PBS and plated on agar plates supplemented with 200 µg ml−1 streptomycin. Plates were incubated for at least 16 h at 37 °C before CFU enumeration, and CFU was reported per gram of faeces for each mouse. S. Tm-selective CFU plating was also done before infection to confirm the absence of streptomycin-resistant aerobic taxa in each microbiome. For C. rodentium (strain DBS100: ATCC51459) infections, strains were grown in LB medium as described above. Mice were infected with around 108 CFUs intragastrically and euthanized at the peak of infection66 (10 dpi), and faecal samples were collected to measure C. rodentium DNA abundance as described below. Intestinal tissues were dissected, washed thoroughly with PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria and then vigorously vortexed to obtain tissue-associated bacterial CFUs, which were enumerated by plating on MacConkey agar plates. For VRE infections, strains were grown in brain heart infusion-supplemented (BHIS) broth overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. Mice were infected with around 108 CFUs per mouse by oral gavage, and euthanized at 1 dpi. Faeces and gut contents were plated on enterococcal agar (BD, 212205) plates supplemented with 8 µg ml−1 vancomycin and 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin.

Survival analysis

Mice were observed twice daily during the experimental period, and those with weight loss of 20% or more, and/or clear morbidity (lethargy, huddling, shivering or hunched posture), were euthanized immediately.

Digoxin administration

Digoxin was freshly prepared in PBS with 5% DMSO before each gavage and administered (5 mg per kg or 0.5 mg per kg) as an oral suspension to mice. PBS 5% DMSO (referred to as PBS controls) was used as vehicle control for all digoxin experiments in mice. The dose of 5 mg per kg mouse body weight was selected on the basis of previous literature24,25,67. This dose led to a slight reduction in weight in C57BL/6NTac, C57BL/6J and Rorc−/− mouse strains, as previously observed68 (Extended Data Fig. 4g), but did not cause other observed distress, morbidity or mortality to mice. Although both the 5 mg per kg and the 0.5 mg per kg dose significantly reduced the levels of SFB and increased the risk of S. Tm infection in mice, we used the higher dose unless otherwise indicated so as to reduce the number of mice required, in light of the intrinsic variability of S. Tm infection in mice that are not receiving streptomycin pretreatment before infection. In some experiments, mice were euthanized at the D0 time point (12 h after the final drug dose, before pathogen infection) for measurement of host gene expression.

Vancomycin administration

Six-to-eight-week-old female C57BL/6NTac mice were treated with vancomycin either orally (25 mg per kg) or intraperitoneally (2.5 mg per kg, to account for the reported 10% bioavailability of oral vancomycin69) for two days (two doses per day), and intraperitoneally administered PBS was used as a control. Mice were euthanized 12 h after the final drug dose, and ileum tissues were collected for gene-expression analysis. Faeces were collected before and after drug treatment for SFB enumeration.

Cohousing experiments

Three-to-four-week-old female C57BL/6J and C57BL/6NTac mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and from Taconic Biosciences, respectively. Mice were tagged and cohoused (two randomly selected C57BL/6J and two C57BL/6NTac mice per cage) for two weeks, and then segregated into new cages according to vendor origin. Segregated C57BL/6J mice were housed together, and digoxin administration and pathogen infection were done as described above, with a high dose of around 109 CFUs per mouse. Experiments with non-cohoused control mice grouped in cages were performed concurrently.

Studies using CV and GF C57BL/6NTac Nramp1 +/+ mice

CV C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice70 were provided by J. E. Galán and were bred in-house at the Yale Animal Resources Center. Six-to-ten-week-old male and female mice were used for drug administration and infection studies as described above. GF C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice were rederived to the GF state by sterile hysterectomy of the CV C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice. In brief, donor CV C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice were time-mated along with GF Swiss Webster dams used for fostering. Forty microlitres of progesterone (NDC, 00143972501) was subcutaneously injected into the pregnant donor mice on the back, near the rump, for three consecutive days before the C-section. On the day of the C-section, the pregnant donor mouse was euthanized by cervical dislocation and submerged in hot (40 °C) Virkon S (Lanxess, 57811373) to disinfect. The pup-loaded uterus was removed and submerged in a 50-ml tube filled with Virkon S. The tube with pups was inserted into the GF isolator containing the GF Swiss Webster foster female. The pups were removed from their amniotic sacs, cleaned with Q-tips, placed with the foster female and monitored until they were accepted. Sterilizing levels of chlorine dioxide (CLIDOX-S: 1:3:1 (Pharmacal, 95120F)) were used to maintain sterility during the procedure. GF status was monitored as described above.

Rorc −/− mice

Heterozygous B6.129P2-Rorctm1Litt/J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (strain 007571)71. Mice were separated according to genotype at weaning, and heterozygous mice were used to maintain the colony. Because this strain is SFB-negative, homozygous (Rorc−/−) mice and their WT littermate controls were colonized with SFB before drug and infection experiments. To this end, the caecal contents from SFB-monocolonized mice were used to colonize GF C57BL/6NTac mice; after four weeks, the GI contents from five mice were collected under sterile anaerobic conditions. All subsequent steps before −80 °C storage were also performed under sterile anaerobic conditions. The contents were weighed, resuspended in 15 ml of sterile, pre-reduced PBS per gram gut contents, vortexed and passed through a 70-µm cell strainer (Fisher, 08-771-2). An equal volume of pre-reduced 40% glycerol (in PBS + cysteine) was added to the flow-through and mixed by inverting. These ‘biobanked’ samples were stored in single-use aliquots in sealed Wheaton vials (Fisher, 03-140-390) at −80 °C. These aliquots were used to colonize Rorc−/− mice and their WT littermates by daily oral gavage beginning at 4–6 weeks of age and continuing for 3 days, followed by an 11-day rest period to allow for SFB expansion and stabilization. SFB engraftment was confirmed using qPCR with SFB-specific primers (Supplementary Table 5). Digoxin administration and pathogen infection was conducted as described above.

ΔILC3 mice

RorcSTOP, Cd4-cre+ mice (which retain Rorc expression in all T cells but lack Rorc expression in ILC3 cells)32 were bred with RorcSTOP, Cd4-cre− mice (which lack Rorc expression in both ILC3 cells and T cells)32 to obtain littermates that either specifically lacked ILC3 cells (designated ∆ILC3) or lacked both ILC3 and TH17 cells (designated RorcSTOP). SFB colonization and digoxin administration were done as described above.

Rag1 −/− mice

GF Rag1−/− (ref. 72) and WT GF control mice were colonized with one dose of SFB caecal contents and administered digoxin or PBS as described above. Mice were euthanized, the ileal contents were collected and weighed and SFB DNA was quantified.

Transgenic C57BL/6NTac Vil-Defb39 mice

Transgenic mice were generated at the Yale Genome Editing Center. The Defb39 gene insert was obtained as a gBlock (Integrated DNA Technologies). The plasmid 12.4kbVillin-ΔATG73 was obtained as a gift from D. Gumucio through Addgene (Addgene plasmid 19358). The Defb39 insert was cloned into the 12.4kbVillin-ΔATG plasmid by InFusion cloning to yield p12.4kbVillin-ΔATG-Defb39 (Supplementary Table 6). The villin promoter and transgene were excised from the plasmid backbone and microinjected into zygote pronuclei as described74. Embryos were transferred to the oviducts of pseudopregnant CD-1 foster females as described74. The presence of the transgene was confirmed by PCR using primers Defb39_F and Defb39_R (Supplementary Table 5). Although the transgenic mice did not show obvious pathology, they did have defects in generating offspring with a functionally overexpressing Defb39 gene, consistent with the reported role of Defb39 in reproductive physiology75 and the activation of the villin promoter in reproductive tissues76,77.

Microbiome transplantation

C57BL/6NTac or C57BL/6J donor mice were treated with digoxin or PBS control (standard 2-day treatment regimen or extended treatment regimens, including a 12-hour drug washout period after the final dose). GI contents were biobanked as described above, except that biobanks were established from individual mice without pooling. Male and female GF C57BL/6NTac recipient mice were singly housed in flexible plastic gnotobiotic isolators, with separate isolators for the recipients of digoxin-treated and PBS-treated biobanked samples. Recipient mice were colonized with biobanked gut microbiomes from digoxin-treated or PBS-treated donor mice in a 1:1 ratio (individual donor to individual recipient). After seven days, recipient mice were euthanized to measure host gene expression, or infected with S. Tm ∆invA as described above. SFB abundance was measured during the course of the transplant by qPCR. Mouse weight, S. Tm ∆invA CFU and survival were measured as described above.

SFB-monoassociation experiments

GF C57BL/6NTac mice were colonized by oral gavage with a single dose of biobanked material from SFB-monoassociated mice (described above). After 14 days, SFB-monoassociated mice were treated with digoxin or PBS as described above. At the D0 time point (12 h after the final dose of digoxin or PBS), mice were euthanized and the ileum tissues and ileum contents were collected for gene-expression studies and quantification of SFB abundance, respectively.

Identification of cgr2-negative human gut communities

Faecal samples from 28 healthy, unrelated human donors were previously obtained, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C in anaerobic conditions under the Yale University Human Investigation Committee protocol number 1106008725 (ref. 12). Previously published and deposited metagenomic data from each donor12 were analysed for cgr2 gene abundance using ShortBRED78. To this end, Cgr2 protein sequences were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in .fasta format, and metagenomic data were retrieved from the European Nucleotide Archive (PRJEB31790). Markers were created using the ShortBRED-Identify function and the UniRef90 reference database79. Abundance of cgr2 was quantified using the created reference markers with the ShortBRED_Quantify function using built-in USEARCH v.11.0.667 (ref. 80). In addition, cgr2 gene abundance was directly measured in aliquots of these samples by qPCR using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 5). The resulting tables for each sample were merged into one summary table (Supplementary Table 7). We selected communities from eight human donors with cgr2 gene levels below the level of detection by either method (Supplementary Table 8) for gnotobiotic mouse studies. These communities were also screened for SFB using qPCR and were SFB-negative.

Colonization of gnotobiotic mice with human-microbiome samples

GF C57BL/6NTac Nramp1+/+ mice (described above) were colonized with either the TH17 -inducing consortium of 20 human gut isolates36, provided by K. Honda (two strains that failed to grow were replaced with the corresponding type strain, as indicated in Supplementary Table 6) or the pooled human-microbiome community by oral gavage. After 14 days, mice were treated with digoxin or PBS for two days as described above. At the D0 time point (12 h after the final drug dose), mice were either euthanized to assess host gene expression using qPCR with reverse transcription (qRT–PCR), or infected with around 108 CFUs of WT S. Tm. Faecal pathogen burden was enumerated at the indicated time points, and mice were euthanized at 4 dpi for enumeration of pathogen loads in different gut compartments, and measurements of ileal gene expression by qRT–PCR.

DNA extraction from mouse faeces

DNA extraction from faecal samples was performed as previously described81. In brief, faecal pellets were collected directly from mice into pre-weighed 2-ml sterile cryotubes at the designated times. The faecal pellets were frozen at −20 °C or directly processed. Faecal pellets were then resuspended in 500 μl CP buffer (Omega), 250 μl SDS 20%, 550 μl of a 25:24:1 phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol mixture (Sigma), 250 μl of 0.1 mm Zirconia silica beads (BioSpec), and one sterilized 5/32″ diameter low-carbon steel ball (McMaster-Carr). The samples were subsequently subjected to disruption using a BeadBeater for two cycles of 2 min and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm at 4 °C, and 200 μl supernatant was used for DNA extraction using the EZ-96 Cycle Pure kit (Omega). Eluted DNA was quantified and diluted 1:100 in sterile water before 16S rRNA-seq or qPCR analysis.

Determining bacterial abundance using qPCR

The abundance of SFB and C. rodentium relative to total bacteria was measured using primers SFB_F and SFB_R (for SFB), EspA_F and EspA_R (for C. rodentium) and EU_F and EU_R (for total bacteria)34 (Supplementary Table 5). qPCR was performed using a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad) and SYBR FAST universal master mix (KAPA Biosystems). Relative abundance was calculated using the ΔCq method.

Assessment of SFB sensitivity to BD-39 antibacterial activity

BD-39 cloning and purification

To purify BD-39 (an orthologue of human BD-1)82, mouse cDNA was used as a template, and the active Defb39 sequence was amplified using Gibson primers (Supplementary Table 5). Bands were gel-excised and cloned into a pET21_NESG vector with a C-terminal His-tag for protein expression and purification.

BD-39 expression

E. coli (BL21) carrying pET21_NESG_Defb39 (Supplementary Table 6) was inoculated into 5 ml LB broth containing ampicillin and grown for 16 h at 37 °C with shaking. The culture was diluted 200-fold in 1 l LB medium containing ampicillin and grown at 37 °C with shaking to the mid-exponential phase (OD600 nm 0.6–0.8). Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 1 mM) was added to induce BD-39 expression. After three hours of induction, the culture was centrifuged, and cell pellets were collected and stored at −80 °C.

Purification, dialysis and concentration of BD-39

Bacterial pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1× BugBuster buffer (Fisher, 709223), 1:3,000 diluted lysonase bioprocessing reagent (Millipore, 71230) and protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A32955)). The lysate was incubated for 30 min at room temperature under mild shaking conditions. The lysate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and incubated with IMAC-Ni resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A50584) for two hours at 4 °C. The mixture was then loaded onto polypropylene columns (QIAGEN, 34964), washed with 20 column volumes of wash buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl and 34 mM imidazole) and eluted with 30 ml elution buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole). The eluates were transferred into 3-kDa Centricon columns (Sigma, UFC700308) and dialysed with 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) three times. The concentrated protein was then stored at −80 °C in 10 mM Tris buffer. The concentration of purified BD-39 was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23225). Control buffer was prepared as above, except that E. coli pET21_NESG (lacking the Defb39 insert) was used in the first step.

In vitro killing assay against representative bacterial strains

Overnight anaerobically grown bacterial strains were resuspended with PBS + cysteine, diluted in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0), treated with varying concentrations of purified BD-39 or control (buffer) and incubated anaerobically in quadruplicate. The inoculum for all strains was diluted to obtain approximately 106 CFUs per ml of live bacterial cells after three hours of incubation. Bacterial cells were plated on de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) agar (Lactobacillus strains), LB agar plates (E. coli and S. Tm), BHI blood agar plates (Bacteroides), and tryptic soy blood agar plates (other anaerobic bacteria), and colonies were enumerated after growing at 37 °C aerobically (for E. coli and S. Tm) or anaerobically (for other bacterial strains). Viability (determined by CFU) of BD-39-treated cultures was normalized to the buffer-treated controls to determine the sensitivity of each strain to recombinant BD-39.

Ex vivo SFB killing assay

All ex vivo steps were performed under anaerobic conditions. The caecal contents of three independent SFB-monoassociated mice were collected, diluted 100-fold in 10 mM Tris buffer and incubated with 10 μM BD-39 or control buffer for 24 h at 37 °C anaerobically. Two groups of GF C57BL/6NTac mice (three mice per group; age and weight matched) were orally gavaged with 200 µl of each incubated sample. Faecal samples were collected and weighed on the indicated days. Faecal DNA was extracted as described above, and the levels of SFB were quantified using qPCR with SFB-specific primers. Caecal DNA from SFB-monoassociated mice was used for the standard curve and to obtain the absolute SFB DNA concentration.

16S rRNA-seq

Amplification and sequencing

The 16S rRNA-seq was performed on samples collected at the D(−2) time point (before drug or PBS administration) and the D0 time point (12 h after the final drug dose). After DNA extraction as described above, the V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced as previously described83. In brief, input genomic DNA was quantified (Quant-IT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit), normalized to 5 ng μl−1 and amplified using barcoded primers84 and AccuPrime Pfx SuperMix. PCR products were cleaned and normalized (SequalPrep, Invitrogen), pooled in sets of 384 samples and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (2 × 250 bp, dual 8-bp indexing, 15% PhiX spike-in) at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis.

The 16S sequencing reported in Extended Data Figs. 7a–c, 9b–e and 10g was done at SeqCoast Genomics. In brief, genomic DNA was extracted as described above and samples were prepared for 16S V3/V4 amplicon sequencing using the Zymo Quick-16S Plus NGS Library Prep Kit (D6421), which uses unique dual indexes.

The forward primer 341f (a mixture of two sequences: CCTACGGGDGGCWGCAG and CCTAYGGGGYGCWGCAG) and the reverse primer 806r (GACTACNVGGGTMTCTAATCC) were used for amplification. The amplification PCR conditions were 95 °C (10 min), 95 °C (30 s), 55 °C (30 s) and 72 °C (3 min), followed by 35 cycles of 3 previous steps, extension for 72 °C (6 min) and hold at 4 °C. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform using a 600-cycle flow cell kit to produce 2 × 300-bp paired reads. A PhiX control (30–40%; unindexed) was spiked into the library pool to support optimal base calling of low-diversity libraries on patterned flow cells. Read demultiplexing, adapter trimming and run analytics were performed using DRAGEN v.4.2.7, an on-board analysis software on the NextSeq 2000. Primer trimming was performed before analysis.

Pre-processing

The 16S rRNA-seq analysis was performed using QIIME 2 (ref. 85). When required, barcode extraction was performed using QIIME v.1.8, and QIIME v.2024.2 was used for subsequent analysis, using emp-paired for the demultiplexing step and DADA2 for truncation and denoising86.

Differential abundance analysis

RESCRIPt was used to prepare a QIIME 2-compatible small subunit (SSU) SILVA reference database based on the curated NR99 (v.138.1) database87,88,89. The classifier was trained based on the V4-targeted or V3/V4-targeted 16S primers as noted above and applied to the sequences. The relative abundance of a given taxon (genus or species level, as indicated) was calculated from the feature count of that taxon in a given sample. Differential abundance analysis was performed using ALDEx2 (ref. 90). To identify significantly altered taxa (P < 0.01), a Welch’s t-test was used.

Beta-diversity analysis

The Bray–Curtis distance matrix was used (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1c) for principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of drug-treated and vehicle-treated mice within the same experimental cohort on D0, or between D(−2) and D0 time points within each mouse group. The weighted UniFrac distance matrix was also used to incorporate phylogenetic distance between sequences in estimates of compositional differences91 (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). The amount of variation using both distance matrices was calculated using PERMANOVA using the Adonis function with 10,000 permutations. The effect size (R2) explains the magnitude of dissimilarities between groups and measures the proportion of microbiome changes that can be explained by the drug (for comparisons between PBS- and drug-treated mice within an experimental cohort) or the time point (for comparisons between time points within each mouse group). P < 0.05 was considered significant. Adonis analysis and visualization were performed using R (v.4.3.0) and the corresponding packages92,93.

SEM

CV C57BL/6NTac mice were treated with digoxin (5 mg per kg or 0.5 mg per kg) or PBS for two days, as described above. At the D0 time point (12 h after the final drug dose), mice were euthanized, and ileum tissues were collected for SEM. In brief, mice were dissected, and approximately 2 mm of ileum tissue was placed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Tissues were changed into a fresh 4% PFA solution after 30 min and incubated at 4 °C overnight, and samples were imaged at the Electron Microscopy Facility at Yale School of Medicine. The samples were pinned open onto silicone pads, and the dissected tissues were refixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4 for one hour. Next, samples were rinsed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4. These were rinsed in buffer and dehydrated through an ethanol series from 30% to 100%. The samples were dried using a Leica 300 critical point dryer with liquid carbon dioxide as the transitional fluid. The samples were glued to aluminium stubs using a carbon graphite adhesive, and sputter coated with 4 nm platinum–palladium using a Cressington 208HR coating unit. Digital images were acquired in a Zeiss CrossBeam 550 between 1.5 kV and 2 kV at a working distance of 8–12 mm.

RNA extraction and qRT–PCR

PBS or digoxin-treated mice were euthanized at the indicated time points. Mice were dissected, and approximately 2 cm of different tissues, including terminal ileum, caecum and colon, were collected. Tissues were flushed to remove the GI contents, rinsed in PBS, transferred into RNAprotect (QIAGEN) and stored at −80 °C. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Universal Mini Kit (QIAGEN, 73404) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration was measured using a plate reader (Take3, BioTek). qRT–PCR was performed as previously described94. In brief, 2 μg of diluted extracted RNA was converted to cDNA with the addition of Superscript II (Invitrogen), random primers (Invitrogen), DTT and dNTPs. For qRT–PCR, validated primers (Supplementary Table 5) and SYBR FAST universal master mix (KAPA Biosystems) were used on a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad). Data were collected and normalized to endogenous Gapdh levels. Fold change was calculated using the ΔΔCq method. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RNA-seq

Sample preparation and RNA extraction

Six-to-eight-week old female C57BL/6NTac mice (three per group) were treated with digoxin or PBS for two days as described above. At the D0 time point, mice were euthanized, the small intestine was dissected and the Peyer’s patches were removed. Approximately 2 cm of the distal small intestine (ileum) was collected, and tissues were flushed and scraped to remove luminal content, transferred into RNAprotect tissue reagent (QIAGEN) and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using the QIAzol chloroform method and the RNeasy Plus Universal Mini Kit (QIAGEN, 73404) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA-seq quality control

Total RNA quality was determined by estimating the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios on a NanoDrop instrument. RNA integrity was determined using an Agilent Bioanalyzer or Fragment Analyzer gel to measure the ratio of ribosomal peaks. Samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) values of 7 or greater were used for library preparation.

RNA-seq library preparation