Abstract

Optical tweezer arrays1,2 have transformed atomic and molecular physics, now forming the backbone for a range of leading experiments in quantum computing3,4,5,6,7,8, simulation1,9,10,11,12 and metrology13,14,15. Typical experiments trap tens to hundreds of atomic qubits and, recently, systems with around 1,000 atoms were realized without defining qubits or demonstrating coherent control16,17,18. However, scaling to thousands of atomic qubits with long coherence times and low-loss and high-fidelity imaging is an outstanding challenge and critical for progress in quantum science, particularly towards quantum error correction (QEC)19,20. Here we experimentally realize an array of optical tweezers trapping more than 6,100 neutral atoms in around 12,000 sites, simultaneously surpassing state-of-the-art performance for several metrics that underpin the success of the platform. Specifically, while scaling to such a large number of atoms, we demonstrate a coherence time of 12.6(1) s, a record for hyperfine qubits in an optical tweezer array. We show room-temperature trapping lifetimes of about 23 min, enabling record-high imaging survival of 99.98952(1)% with an imaging fidelity of more than 99.99%. We present a plan for zone-based quantum computing5,21 and demonstrate necessary coherence-preserving qubit transport and pick-up/drop-off operations on large spatial scales, characterized through interleaved randomized benchmarking. Our results, along with recent developments8,22,23,24, indicate that universal quantum computing and QEC with thousands to tens of thousands of physical qubits could be a near-term prospect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Optical tweezer arrays1,2 have transformed atomic and molecular physics experiments by simplifying detection and enabling individual-particle control25,26,27, resulting in rapid, recent progress in quantum computing3,4,5,6,7,8, simulation1,9,10,11,12 and metrology13,14,15. In this context, each atom typically encodes a single qubit that is controlled with electromagnetic fields and ideally features long coherence times to enable these applications with high fidelity. Such optically trapped atomic qubit devices coexist with other platforms that have single-qubit control and readout, including ion traps28 and superconducting qubits29.

There are important incentives to scale up such fully programmable qubit platforms. Optical atomic clocks gain stability with increasing atom numbers30, while quantum simulation experiments benefit from thousands of qubits to explore emergent collective phenomena31,32 or demonstrate verifiable quantum advantage33,34. Most critically, QEC demands both large system sizes and exceptional fidelities: even the most resource-efficient protocols require several thousand physical qubits operating with error rates less than 10−3 to encode more than 100 logical qubits20,35. This represents a fundamental scalability challenge that has limited the practical impact of quantum technologies.

Present universal quantum computing architectures, such as those based on neutral atoms5,6,7,8, ions28 and superconducting qubits29, typically operate with tens to hundreds of qubits. Although most platforms suffer from increasingly deleterious effects as system size grows28,29, neutral atoms in optical tweezer arrays offer a promising solution for rapid scalability in the near term thanks to a programmable architecture adaptable to larger system sizes.

Universal quantum computing capabilities with neutral atoms have recently been realized in optical tweezer array systems, based on demonstrations of individual qubit addressing36,37,38,39, high-fidelity entangling gates8,22, coherence-preserving dynamical reconfigurability5,8,40 and ancilla-based mid-circuit measurement8,21,41. Very recently, tweezer systems with about a thousand atoms have been realized in a discontiguous array based on interleaved microlens elements16 and by means of repeated reloading from a reservoir17,18; none of these experiments, however, report control of qubits, measurement of coherence times or coherence-preserving transport.

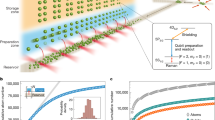

Here we demonstrate a tweezer array with 11,998 sites that traps more than 6,100 atomic qubits, simultaneously matching or surpassing state-of-the-art values for metrics underpinning the usefulness of the platform, including hyperfine qubit coherence time, trapping lifetime in a room-temperature apparatus, coherent transport distance and fidelity, trap transfer fidelity, as well as combined imaging fidelity and survival (Fig. 1). Our results have implications for the aforementioned applications in quantum science, in particular, concerning large-scale quantum computing and error correction, as discussed in more detail below.

a, Representative single-shot image of single caesium atoms across an 11,998-site tweezer array. Inset, magnified view of a subsection of the stochastically loaded array. b, Averaged image (from 16,000 experimental iterations) of single atoms across an 11,998-site tweezer array. Inset, magnified view of a subsection of the averaged array. Atoms are spaced by 7.2 μm and held in 1,061-nm and 1,055-nm optical tweezers. The contrast is enhanced for visual clarity. c, Schematic of the optical tweezer array generation. Tweezer arrays, generated by two SLMs, at 1,061 nm and 1,055 nm are combined on a polarizing beam splitter (PBS) with orthogonal polarization and focused through an objective with a NA of 0.65 and a field of view (FOV) 1.5 mm in diameter. The direction of gravity is along \(\widehat{y}\). We collect scattered photons from single atoms through the same objective and image them on a qCMOS camera. d, Histogram of filling fraction. We load 6,139 single atoms on average per experimental iteration (51.2% of the array on average), with a relative standard deviation of 1.13% over 16,000 iterations. e, Summary of the key metrics demonstrated in this work. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Summary of approach and results

Our approach makes use of high-power trapping of single caesium-133 atoms at far-off-resonant wavelengths in a specially designed, room-temperature vacuum chamber (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1a), enabling low-loss, high-fidelity imaging in combination with long hyperfine coherence times at the scale of 6,100 qubits (Fig. 1e). Specifically, we demonstrate single-atom imaging with a survival probability of 99.98952(1)% and a fidelity of 99.99374(8)%, surpassing the state of the art achieved in much smaller arrays42. This, together with a 22.9(1)-min vacuum-limited lifetime in our room-temperature apparatus43—much longer than typical state-of-the-art vacuum lifetimes for tweezer arrays in room-temperature apparatuses—provides realistic timescales for array operations in large-scale arrays with minimal loss, for example, for atomic rearrangement25,26,27.

Notably, we further demonstrate a coherence time of 12.6(1) s, a record for a hyperfine qubit tweezer array, surpassing previous values by almost an order of magnitude5,6. We also show a single-qubit gate fidelity of 99.9834(2)% measured with global randomized benchmarking.

Finally, we demonstrate coherent atomic transport across 610 μm with a fidelity of about 99.95% and coherent transfer between static and dynamic traps with a fidelity of 99.81(3)%. These together form crucial ingredients for scaling atomic quantum processors in a zone-based architecture, with a detailed plan laid out further in the Supplementary Information. Our results indicate that quantum computing with 6,000 atomic qubits is a near-term prospect, providing a path towards QEC with hundreds of logical qubits20.

Large-scale optical tweezer generation

To scale the optical tweezer array platform, while extending hyperfine coherence times, we generate traps using near-infrared wavelengths, far-detuned from dominant electric-dipole transitions, thus minimizing photon scattering and dephasing processes44. Caesium atoms have the highest polarizability among the stable alkali-metal atoms at near-infrared wavelengths at which commercial fibre amplifiers provide continuous-wave laser powers that exceed 100 W. Thus, a large number of traps can be created with sufficient depth. A representative single-shot image of the array is shown in Fig. 1a and an averaged image is shown in Fig. 1b.

The atoms are spaced by approximately 7.2 μm and held in traps at 1,055 nm and 1,061 nm, generated using spatial light modulators (SLMs), whose hologram phases are optimized with a weighted Gerchberg–Saxton (WGS) algorithm45 to make the tweezer trap depth uniform (Methods). The tweezer light is combined with polarization and focused through a high numerical aperture (NA) objective with a large field of view 1.5 mm in diameter, usable for atom trapping and manipulation (Fig. 1c).

The tweezers are created with 130 W of optical power generated from fibre amplifiers. After transmission through the optical path, around 35–40 W reaches the objective, and from trap parameter measurements (see the ‘Tweezer generation’ section in Methods), we estimate about 1.4 mW to be used per tweezer at the atom plane. We measure an average trap depth of kB × 0.18(2) mK, with a standard deviation of 11.4% across all sites (Extended Data Fig. 2d), enabling consistent loading probability per site.

Loading and imaging single atoms

We demonstrate uniform loading and high imaging fidelity across the sites in the array. To load single atoms in the tweezers, we cool and then parity-project from a roughly 1.6-mm 1/e2 diameter magneto-optical trap (MOT). Before imaging the atoms, we use a multipronged approach to filter out atoms in spurious off-plane traps, residual from the SLM tweezer creation (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 3).

We then zero the magnetic field and apply 2D polarization gradient cooling (2D PGC) in the atom array plane (x–z plane in Fig. 1c) for fluorescence imaging of single atoms, which simultaneously cools the atoms. Imaging light is applied for 80 ms and photons are imaged on a quantitative CMOS (qCMOS) camera. We find that each site has a loading probability of 51.2% with a relative standard deviation of 3.4% across the sites, demonstrating uniform filling of single atoms (Extended Data Fig. 2c). This allows us to load more than 6,100 sites on average in each iteration (Fig. 1d).

We distinguish atomic presence in the array with high fidelity. Each image undergoes a binarization procedure (Methods), in which each site is attributed a value of 0 (no atom detected) or 1 (one atom detected). We weight the collected photons in a 7 × 7-pixel box centred around each site, to add more weight to pixels close to the centre of the point-spread function of each site (Extended Data Fig. 4a). The resulting signal is compared with a threshold to determine whether an atom is present or not (Fig. 2).

Imaging histograms showing the number of photons collected per site and per image collected from 16,000 experimental iterations. Note that the horizontal axes are weighted photon counts (see text); for non-weighted photon counts, see Extended Data Fig. 4b. a, Imaging histogram of three randomly selected sites in the array (in which x and y respectively denote the horizontal and vertical site indices in the array). b, Histogram averaging over all sites in the array. Per-site histograms are fitted with a Poissonian model that integrates losses during imaging (Methods). The wide separation of peaks for empty and filled tweezers enables the high imaging fidelity presented in this work. The binarization threshold used to determine tweezer occupation is indicated by the vertical dashed line and the average point-spread functions for the two classifications (atom absent and atom detected) are shown next to their corresponding peaks. Note that we detect no more than one atom in each tweezer. Inset, the same histogram presented with a log-scale vertical axis. The weighted average relative error bar per bin is 0.08% (0.05% for the log-scale inset owing to the smaller number of bins).

We characterize the imaging fidelity, defined as the probability of correctly labelling atomic presence in a site, with a model-free approach, for which no assumption is made about the photon distribution from Fig. 2. To this end, we identify anomalous series of binary outputs46 in three consecutive images. For instance, 0 → 1 → 1 would point to a false-negative event in the first image, whereas 1 → 1 → 0 could be because of atom loss during the second image or a false-negative event in the third one. This approach allows us to precisely decouple inherent atom loss from false negatives or positives. From this, we find an imaging fidelity of 99.99374(8)% (note that we excise the first image, which we find has slightly lower fidelity and survival probability; Methods). Crucial to this result is the homogeneous photon scattering rate across the array (Extended Data Fig. 4d) and the consistency of the point-spread function across the array (waist radius of 1.7 pixels with a standard deviation of 0.2 pixels). Consistent imaging parameters across the array are further evidenced in that we find that treating each site with an individual threshold only marginally improves the imaging fidelity to 99.9939(1)%. Finally, we estimate that the imaging fidelity in the absence of atomic loss would be closer to 99.999% (Methods).

Imaging survival and vacuum-limited lifetime

The probability of losing no atom in a tweezer array during imaging and because of finite vacuum lifetime both decrease exponentially in the number of atoms in an array, making these metrics crucial to optimize for large-scale array operation. The vacuum-limited lifetime, in particular, sets an upper bound on the duration during which operations can be executed without loss of an atom in a given experimental run. This can, for example, be applied as an upper limit on the fidelity with which we can achieve a defect-free array through atom rearrangement25,26.

We investigate the vacuum-limited lifetime using an empirically optimized cooling sequence consisting of a 10-ms 2D PGC cooling block every 2 s. By fitting the exponential decay of the atom survival, we find a 1/e lifetime of 22.9(1) min (Fig. 3a). This is a much longer timescale compared with state-of-the-art room-temperature atomic experiments and within a factor of five of the longest reported lifetime in a cryogenic apparatus43. The result indicates that the probability of losing a single atom across the entire array remains less than 50% during 100 ms, a relevant timescale for dynamical array reconfiguration and quantum processor operation.

a, Vacuum-limited lifetime. Array-averaged survival fraction as a function of hold time is plotted. Three experiments are shown in the figure: pulsed cooling, continuous cooling and no cooling. The green markers show data with a 10-ms 2D PGC block applied every 2 s during the wait time (pulsed PGC), the red markers show data with a 2D PGC block continuously applied during the wait time (continuous PGC) and the blue markers show the data without cooling during the wait time (no PGC). The error bars are smaller than the markers. We find a 1/e lifetime of around 2.2 min without cooling. When the pulsed PGC block is applied, by fitting the data with p(t) ∝ exp(−t/τ), we find a vacuum lifetime of τ = 22.9(1) min. When the 2D PGC is applied continuously, we obtain τ = 17.7(2) min. b, Array-averaged survival fraction after many successive images. Between each image, we hold the atoms for 10 ms, without applying any cooling beams. We fit the data with \(p(N)\propto {p}_{1}^{N}\), in which p(N) is the survival fraction after imaging N times. From the fit, we find a steady-state imaging survival probability of p1 = 0.9998952(1). The light purple fill shows the estimated 68% confidence interval.

Moreover, we accurately characterize the imaging survival probability, without assuming any parameters, by performing 80-ms repeated imaging up to 1,000 times, after which approximately 90% of initially loaded atoms still survive (Fig. 3b). This corresponds to a steady-state imaging survival probability of 99.98952(1)%, mostly limited by vacuum lifetime. This, to the best of our knowledge, surpasses previous studies reporting record steady-state imaging survival using single alkaline-earth-metal42 and alkali-metal47 atoms in optical tweezers. These results, and the uniformity of imaging survival across the array (Extended Data Fig. 5a), enable low-loss, high-fidelity detection of single atoms in large-scale arrays, crucial components for the practical use of the system. In Extended Data Fig. 6, we present imaging fidelity and survival results with a shorter imaging duration of 20 ms.

Qubit coherence

Key to recent progress in quantum computing and metrology with neutral atoms is the ability to encode a qubit in long-lived states of an atom, such as hyperfine states5,6, nuclear spin states36,37,38 or optical clock states13,14. In caesium atoms, the hyperfine ground states (|F = 3, mF = 0⟩ ≡ |0⟩ and |F = 4, mF = 0⟩ ≡ |1⟩) provide such a subspace for storing quantum information (see Methods for state preparation and readout procedures). Furthermore, entanglement by means of Rydberg interactions can be readily transferred to this qubit to realize high-fidelity two-qubit gates22. We demonstrate the storage and manipulation of quantum information in a large-scale atom array by measuring the coherence time and global single-qubit gate fidelity using a microwave horn to drive the hyperfine transition (Fig. 4a). For microwave operation, we adiabatically ramp down tweezers to a depth of kB × 55 μK.

a, Array-averaged Rabi oscillations between the hyperfine clock states |0⟩ and |1⟩. The fitted Rabi frequency is 24.611(1) kHz. The observed decay after several hundred microseconds arises from the spatially varying Rabi frequency (Extended Data Fig. 7b). b, Array-averaged Ramsey oscillations. During free evolution, the microwave drive field is detuned by 1 kHz, resulting in Ramsey oscillations. The characteristic decay time of these oscillations is \({T}_{2}^{* }=14.0(1)\,{\rm{ms}}\) from fitting the average signal of all atoms. The light blue dashed line shows the decay time \({T}_{2}^{* ({\rm{site}})}=25.5\,{\rm{ms}}\) from fitting individual sites first and averaging the decay time afterwards. c, Measurement of the dephasing time T2 after dynamical decoupling. After an initial π/2 pulse, a variable number of XY16 dynamical decoupling cycles with a fixed time τ = 12.5 ms between π pulses are used to offset the reversible dephasing. The phase of the final π/2 pulse is chosen to be either 0 or π and subtracting the population difference in these two cases provides the coherence contrast. The contrast decay is fitted to obtain T2 = 12.6(1) s. d, Randomized benchmarking of the global single-qubit gate fidelity. For each number of Clifford gates, 60 different random gate strings of this length are applied, after which the overall inverse of the string is applied. For a given gate string length, each translucent marker of a given colour represents the return probability for a string of gates, while the solid green markers indicate the averaged return probability over the 60 different strings. The inset lists all of the colours used to indicate the 60 random gate strings for a given length. The decay of the final population to 1/2 is fitted to (1 − d)N and Fc = 1 − d/2 represents the average Clifford gate fidelity.

Preserving the coherence of a quantum system as it is scaled up is a known challenge across platforms for quantum computing and simulation29. This difficulty persists even for neutral atoms, albeit at a lower level, owing to residual interactions with a noisy and inhomogeneous electromagnetic environment, particularly with the tweezers themselves. Thus, we choose to trap in far-off-resonant optical tweezers to preserve coherence, because at constant trap depth, the differential light shift of the hyperfine qubit decreases as 1/Δtweezer and the scattering rate as \(1/{\Delta }_{{\rm{tweezer}}}^{3}\), in which Δtweezer is the tweezer laser detuning relative to the dominant electronic transition44. We indeed observe long coherence times, measuring a depolarization time of T1 = 119(1) s (Extended Data Fig. 7d) and an array-averaged ensemble dephasing time of \({T}_{2}^{* }=14.0(1)\,{\rm{ms}}\) (Fig. 4b), limited by trap depth inhomogeneity. Measured site by site, the dephasing time is \({T}_{2}^{* ({\rm{site}})}=25.5\,{\rm{ms}}\), consistent with being limited by an atomic temperature of about 4.3 μK during microwave operation (Methods). In Extended Data Fig. 8 and Methods, we present and discuss site-resolved qubit coherence data.

The dephasing can be further mitigated by dynamical decoupling. By applying cycles of XY16 sequences48 with a period of 12.5 ms between π pulses, the measured dephasing time is T2 = 12.6(1) s, a new benchmark for the coherence time of an array of hyperfine qubits in optical tweezers5,6 (Fig. 4c). Also, we investigate in Extended Data Fig. 7g the coherence time at different trap depths, yielding notably T2 = 3.19(5) s at the full trap depth of kB × 0.18 mK. Although lower, this result also surpasses previously known results with hyperfine qubits in a tweezer array.

Finally, we determine single-qubit gate fidelities through global randomized benchmarking49. To compensate for the inhomogeneous Rabi frequency across the array, we use the SCROFULOUS composite pulse50. We apply gates sampled from the Clifford group C1, followed by an inverse operation, and measure the final population in |1⟩ (Fig. 4d). Fitting the decay as the number of gates increases yields an average Clifford gate fidelity Fc = 0.999834(2), limited by phase noise in our system likely due to magnetic field noise (Methods). This could be readily addressed by upgrading the current sources driving the magnetic field coils or by operating at MHz-scale Rabi rates with optical Raman transitions (notably used to perform sideband spectroscopy in Extended Data Fig. 9).

Coherent long-distance transport and atom transfer

We now focus more specifically on the practical implementation of a quantum computer, as it is a flagship application of our work and because it demands the most sophisticated toolbox of aforementioned use cases. Universal quantum computing requires local single-qubit and two-qubit gates, which have been implemented either through single-site addressing6 or a zone-based architecture5,21. Zone-based architectures make use of the ability to dynamically move atoms in a coherence-preserving manner5,40, enabling long-range, non-local connectivity, which allows for less stringent QEC bounds51. This architecture also provides a path for mid-circuit readout21. We depict a possible zone layout in Extended Data Fig. 10a and the Supplementary Information, which includes a storage zone large enough for more than 6,100 atoms. We do not foresee challenges in creating the zones themselves, for example, Rydberg-based two-qubit gates should be feasible in a large interaction zone for more than 500 gates in parallel with state-of-the-art fidelities (Supplementary Information Section IV).

However, coherence-preserving transport between storage and adjacent interaction or readout zones might require covering large distances of about 500 μm. Although moving atoms using acousto-optic deflectors (AODs) is now a well-established practice to resort them into a deterministic configuration25,26 or to transport them coherently5,8,21,39, this distance is much farther than previously demonstrated distances for single-atom transport with tweezers5,21. Furthermore, transferring atoms between dynamic (AOD-generated) and static (SLM-generated) tweezers requires precise relative alignment, conceivably challenging in our system owing to the high laser power or potential for worsening aberrations over the large field of view.

Thus, we investigate the feasibility of coherence-preserving transport and SLM–AOD trap transfer over larger length scales. First, isolating challenges with the coherent transport operation, we load atoms directly into ten AOD-generated tweezers and characterize coherent moves up to about 610 μm (Fig. 5 and top section of Extended Data Fig. 10). Second, we assess the viability of large-scale parallel AOD–SLM trap transfers with 195 AOD-generated tweezers that span a square of dimensions 504 μm × 468 μm (Fig. 6). As an outlook, we demonstrate a proof-of-principle combination of these techniques in a large-scale static array (although in a different trap layout) moving a 2D array of 47 atoms over 375 μm, a distance comparable with predicted zone spacings in our system (Extended Data Fig. 10e,f). For all operations, we use the most wide-band commercially available AODs at near-infrared wavelengths, which cover up to 500–600 μm along one axis for the optical parameters used here (Methods).

a, Schematic and atom survival for a diagonal (blue) or straight (pink) move for ten tweezers (with depth kB × 0.28 mK) spaced by about 10.6 μm. Despite being shorter, a straight move needs to be executed more slowly than a diagonal one owing to cylindrical lensing. b, Coherence of an atom after being transported diagonally 610 μm (blue) in 1.6 ms or held stationary (grey). c, IRB sequence used to benchmark the move fidelity. Random Clifford gates are interleaved between each of the M (<N) moves, with the total number of gates N constant. d, Benchmarking results for repeated 610-μm diagonal moves. Top, atom survival for varied times, fitted to a clipped Boltzmann distribution (Methods). 1.6-ms moves are used for the middle and bottom panels. Middle, IRB return probability for static and transported atoms. Curves are fits that include coherence and atom losses (Methods). Bottom, average instantaneous transport fidelity after a given number of moves, fitted from the IRB return probability (Methods). The curve width represents the 68% confidence interval. The instantaneous fidelity of 99.953(2)% is constant for the first approximately 30 moves.

a, Layout of the transfer experiment showing 195 dynamic AOD traps (bright blue) overlapped with 1,061-nm static SLM traps (pale blue). Atoms are repeatedly picked up and moved away by 2.4 μm, then held for 100 μs. During this time, the SLM traps are turned off to ensure that atoms left behind in SLM traps are removed (this way, atom survival correctly corresponds to a successful pick-up and drop-off). SLM traps are subsequently turned back on and atoms held in AOD tweezers are moved back and dropped off into the SLM traps. For IRB data shown in d, gates are interleaved between each round-trip transfer. A pick-up and split-move operation (or equivalently a merge-move and drop-off operation) is considered a ‘one-way transfer’. b, Best hand-optimized trajectory for trap transfer (Methods), using a quadratic depth profile and a constant jerk movement. Here we implement the pick-up and the tweezer separation move in sequence, without overlap. c, To speed up atom transfer between static and dynamic traps while preserving high survival, we optimize, through machine learning, a trajectory in which dynamic AOD traps are simultaneously ramped and moved. The dashed lines and black dots represent the values that are optimized by the algorithm. d, Top, atom survival as a function of the number of repeated one-way transfers for various one-way ‘pick-up and split' total durations. A 400-μs trajectory is optimized through machine learning. Middle, return probability after IRB for the machine-learning-optimized trajectory. Bottom, extracted instantaneous fidelity of a coherent one-way transfer as a function of the number of previous one-way transfers.

In consideration of atom survival as a function of long-distance movement speeds, we find that the speed of transport is strongly constrained by cylindrical lensing—an effect that occurs when the AOD frequency is rapidly swept52—which becomes increasingly deleterious as the AOD field of view is increased (Supplementary Information Section III.A). Notably, using a pair of crossed AODs for diagonal transport converts cylindrical lensing into spherical lensing, enabling substantially faster movement (Fig. 5a). With diagonal moves, we first demonstrate in Fig. 5b negligible loss of coherence for atoms transported by 610 μm in 1.6 ms. We suppress dephasing with one XY4 dynamical decoupling sequence per move.

Realistic applications of coherent transport involve several consecutive moves. Therefore, we characterize the fidelity of the quantum channel defined by coherent transport through interleaved randomized benchmarking53 (IRB; Fig. 5c and Methods). To the best of our knowledge, such a quantitative characterization of transport fidelity in neutral atoms has not been previously demonstrated. To maximize the dephasing cancellation, we apply dynamical decoupling in a transformed Clifford frame (Methods).

We perform this benchmarking technique for a distance of 610 μm (Fig. 5d), with diagonal moves. We first measure the survival probability of an atom in a tweezer at the end of the sequence for different move durations (top panel). For a 1.6-ms move using kB × 0.28-mK-deep traps, we then characterize the return probability to the initial quantum state after IRB as a function of the number of moves (middle panel). Other distances, trap depths and move times are shown in Extended Data Fig. 10.

The resulting IRB return probability data are non-exponential in the number of moves, because at large numbers of moves, trap losses become dominant and the fidelity for the transport channel depends on the number of previously executed moves. This motivates defining an instantaneous fidelity, that is, the fidelity of the transport channel after a certain number of previous moves (Methods), shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 5d. The instantaneous fidelity approaches a constant value of 99.953(2)% for small numbers of one-way moves (≲30), for which losses are the sub-dominant error. This regime is most relevant for QEC, as data qubits and ancilla qubits can, in principle, be swapped every few layers of gates54.

We then move on to characterizing the atom transfer between static and dynamic tweezers. We demonstrate that these operations proceed without the emergence of unexpected technical challenges by performing high-fidelity parallel AOD–SLM transfer across the full field of view of the AOD (Fig. 6).

We use 195 AOD tweezers spread across 504 μm × 468 μm (Fig. 6a) to perform and characterize the repeated transfer procedure, post-selected on initially filled SLM sites. As with coherent transport benchmarking, we evaluate the transfer fidelity as a function of the number of one-way transfers through IRB (Fig. 6d). To execute faster (or higher-fidelity transfers at a given duration), we propose and implement a trajectory on which AOD ramp-and-move operations are simultaneously optimized with machine learning techniques to maximize survival (Fig. 6c and Methods). Compared with our manually optimized trajectory (Fig. 6b), this technique yields much higher atomic survival and enables a one-way transfer fidelity of 99.81(3)% for ≲12 transfers.

In the future, such machine learning techniques could also be used to optimize combined pick-up and transport, for which we find a fidelity of 99.87(1)% for the first approximately 12 operations at the chosen timescales with manually optimized methods (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 10f).

Finally, to cover the full extent of the array, we propose using several pairs of crossed AODs, with the demonstrated long-distance transport allowing overlap between adjacent AOD-pair controlled regions (Supplementary Fig. 2). With the layout presented in Extended Data Fig. 10a and the Supplementary Information, four such regions would be necessary. Alternatively, further scanning techniques (for example, fast-scanning mirrors) can be used to position the field of view of a single pair of crossed AODs across the full array iteratively.

Such techniques are also applicable to initial rearrangement of atoms in the storage zone. For example, by implementing a parallel assembly algorithm55,56 in four quadrants (Supplementary Information Section II), with estimates for relevant timings based on simulation, data and previous experiments (Supplementary Table 1), we expect that we can sort the array in parallel in about 137 ms or sequentially quadrant by quadrant in about 522 ms.

Conclusion and outlook

We have shown scaling of neutral-atom qubit numbers in optical tweezers to more than 6,100. We simultaneously achieve high imaging survival and fidelity as well as a long room-temperature vacuum-limited lifetime. We find record coherence times in alkali-metal atom tweezer arrays and a high global single-qubit gate fidelity, limited by technical noise. Further, we also characterize the fidelity of quantum transport channels for moves and trap transfer at relevant length scales, using randomized benchmarking.

Our results usher in a new generation of neutral-atom quantum processors based on several thousand qubits, particularly relevant for QEC20,35. Furthermore, large-scale programmable devices enabling advances in quantum metrology8,13,14,15,30 and simulation31,32,33 are made accessible through this work. For example, our platform—with the demonstrated qubit numbers—could be used for verifiable quantum advantage with low-depth evolution33,34. Tweezer clocks could be scaled using near-infrared, high-power tweezers for loading and imaging57 before transferring atoms to magic-wavelength traps for clock operation8,13,14,15. We also foresee applications in quantum simulation for problems in which boundary effects play an important role1,9,10,11,31, which can be minimized with the large system sizes demonstrated here.

Finally, our work indicates that further scaling of the optical tweezer array platform to tens of thousands of trapped atoms should be achievable with present technology, while essentially preserving high-fidelity control. In our present apparatus, several factors limit the number of sites. One limitation is the finite number of pixels of each SLM (reducing the diffraction efficiency as the array size is increased), along with reduced SLM diffraction efficiency at higher incident laser powers. By using available higher-resolution SLMs, and by exploring techniques with higher pixel modulation depth58, we hope to use both power and field of view more efficiently.

Furthermore, we observe worsening optical aberrations at tweezer powers greater than that in the present study owing to thermal heating of the objective. This is the main limitation on atom number for the results in this work, even after aberrations were mitigated using the SLM (Methods). This constraint could be circumvented by using an objective with a housing material that retains less heat or with integrated cooling strategies. Such upgrades should allow us to almost double the number of tweezers that we create using two fibre amplifiers. We further anticipate the potential to switch from polarization combination to wavelength-based array combination, opening further avenues for increasing tweezer number with similar techniques to those used in this work. Atom numbers may further be increased in our array with the same number of tweezers by using enhanced loading59 or reloading techniques17,60. Already in the near term, we expect to increase the number of atomic qubits to more than 10,000 with the present system using a subset of these techniques.

Methods

Vacuum apparatus

A schematic of our vacuum system is shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. After the initial chamber assembly and multiround baking process, we fire two titanium sublimation pumps (TSPs), mounted such that every surface except the rectangular portion of the glass cell and the interior of the ion pump are covered by line-of-sight sputtering. This creates a vacuum chamber in which essentially every surface is pumping. We do not find it necessary to refire the TSPs to maintain the vacuum level that we measure. We also maintain ultrahigh-vacuum conditions with an ion pump, connected to the primary chamber through a 45° elbow joint. The secondary, science, chamber consists of a rectangular glass cell (Japan Cell) optically bonded to a 24-cm-long glass flange (also sputtered by the TSP) that connects to the primary chamber. From lifetime measurements of tweezer trapped atoms (see the main text) and collisional cross-sections available in the literature61, we estimate the pressure in the glass cell to be about 7 × 10−12 mbar, consistent with vacuum simulations using the MolFlow program62.

Tweezer generation

We use light from two fibre amplifiers, at 1,061 nm (Azurlight Systems) and 1,055 nm (Precilasers), to create the optical tweezers through an objective (Special Optics) with NA = 0.65 at the trapping wavelengths (NA = 0.55 at the imaging wavelength of 852 nm) and a field of view of 1.5 mm. The tweezers are imprinted onto the light in each pathway by a Meadowlark Optics phase-only liquid crystal on silicon SLM that is water-cooled to maintain a temperature of 22 °C. On each path, there are two 4f telescopes used to map the SLM phase pattern onto the back focal plane of the objective, which subsequently focuses the tweezers into the vacuum cell as shown in Fig. 1c. In the first focal plane after the SLM, we perform spatial filtering on the two paths to remove the zeroth order and reflect the first-order diffracted light from the SLM. On the 1,061-nm path, we use two D-mirrors spaced by a few hundred microns and on the 1,055-nm path, we use a mirror with a manufactured 300-μm hole as spatial filters to separate zeroth-order light from the tweezer light. The 1,055-nm tweezers are essentially used to fill the gap between two halves of the array created by the 1,061-nm tweezers (Extended Data Fig. 2a), although we anticipate increasing the number of tweezers created with this path after implementing the objective heat-dissipation strategies as described in the ‘Conclusion and outlook’ section. At present, we use 120 W of power from the 1,061-nm fibre amplifier and around 10 W of power from the 1,055-nm fibre amplifier to create the tweezers. On the 1,061-nm path after all of the optical elements, we estimate that only around 35–40 W of the total power reaches the objective and, given measurements of trap parameters, that we have roughly 1.4 mW per tweezer. At low optical power, we estimate a ratio between the incoming power and the light diffracted into the first order of the SLM of around 65% into the full array and at full optical power, we estimate a diffraction efficiency of around 45%, even after optimizing the SLM global calibration at high power. We leave further improvement to future work.

Although we would like to separate the first-order hologram phase pattern and zeroth-order reflection in a more convenient manner, the largest angular separation that is possible between the zeroth and first orders of the SLM, as determined by the SLM pixel size, would not separate the large tweezer array from the zeroth order, owing to the large angular distribution of the tweezers. Furthermore, the diffraction efficiency of the SLM into the first order decreases with increasing separation from the zeroth order. Therefore, it is the most power-efficient choice to centre the tweezers around the zeroth order and to filter it at the first focal plane after the SLM. This decreasing diffraction efficiency with increasing distance from the zeroth order, at the centre of the array, informs our choice of a circular tweezer array. We highlight the development of these techniques of zeroth-order filtering as uniquely necessary for a large-scale array.

The SLM phase patterns are optimized with a WGS algorithm45,63,64,65 to create a tweezer array that we make uniform through a multistep process, first adjusting weights in the algorithm based on photon count on a CCD camera that images the tweezers63 and second adjusting weights based on the loading probability of each site in the atomic array with a variable gain feedback, as demonstrated on smaller arrays in previously developed schemes66. We implement around five iterations of each step to achieve the loading and survival probabilities that are shown in Extended Data Figs. 2c and 5a. The WGS goal weight Wi on each tweezer for the ith iteration is given by

normalized by the mean weight ⟨Wi⟩, in which the height Hi is determined by adjusting the value from the previous iteration using the loading probability per tweezer Pload, normalized by the average loading probability,

We choose the gains G and g to reach convergence for the given configuration of tweezers (here we use a value of 0.6 for each) and also add a cap to the allowable values of Hi to avoid oscillatory behaviour. We show in Extended Data Fig. 2b the weights for tweezers for different angular diffraction off of the SLM, obtained after using the loading-based uniformization. We also show the theoretical weights that would be expected on the basis of the inverse of the naive diffraction efficiency calculations for blazed gratings. The diffraction efficiency is given by \({\rm{DE}}={{\rm{sinc}}}^{2}\left(\frac{{\rm{\pi }}ax}{\lambda f}\right){{\rm{sinc}}}^{2}\left(\frac{{\rm{\pi }}ay}{\lambda f}\right)\), in which a is the SLM pixel size, x and y are the horizontal and vertical displacements from the zeroth order at the tweezer plane, f is the effective focal length of the objective and λ is the trapping wavelength. We expect that some divergence in behaviour could be caused by angular-dependent transmission in optics in the imaging path.

We furthermore add aberration correction to the SLM phase hologram based on Zernike polynomials67. We perform a gradient-descent-type optimization to determine the amplitude of the Zernike polynomial coefficients that maximizes the filling fraction in the array. We iterate between this optimization and 2–3 rounds of loading-based uniformization.

To align the tweezers created by the two fibre amplifiers in angle, we change the goal configuration for the WGS algorithm. The CCD camera on which we image the tweezers after the vacuum cell provides a helpful reference for this alignment.

Loading single atoms in tweezers

The typical experimental sequence can be seen in Extended Data Fig. 1c. From an atomic beam generated with a 2D MOT of caesium-133 atoms (Infleqtion CASC), we load roughly 107 atoms in the 3D MOT in 100 ms using three pairs of counter-propagating beams and create a roughly 1.6-mm 1/e2 diameter MOT cloud. The magnetic field gradient is set to 20 G cm−1 with a quadrupole configuration using a pair of coils that is perpendicular to the objective axis. Each beam has a size of 2.5 cm in diameter, detuning of Δ = −3.17Γ from the bare atom |6S1/2, F = 4⟩ ↔ |6P3/2, F′ = 5⟩ resonant transition (Extended Data Fig. 1b) and a total intensity of 10I0 (1.6I0 for repumping beams), in which I0 ≈ 1.1 mW cm−2 is the saturation intensity of the transition between the stretched states and Γ ≈ 2π × 5.2 MHz is the natural linewidth of the 6P3/2 electronically excited state68. After loading atoms into the 3D MOT, we switch off the quadrupole magnetic field and, at the same time, lower the intensity to 7I0 and detune the laser further to Δ = −19.5Γ to cool atoms below the Doppler temperature limit through 3D PGC, which loads atoms into approximately kB × 0.18-mK depth tweezers and parity projects the number of atoms in a tweezer69 to either 0 or 1. This 3D PGC is applied for 40 ms, after which we wait another 40 ms for the remaining atomic vapour from the MOT to drop and dissipate. The optical tweezer array is kept on for the whole duration of the experiment.

Generating optical tweezers with a SLM results in weak out-of-plane traps that can trap sufficiently cold atoms from the MOT70. This could lead to a strong background in the image or to false-positive detections of single atoms, both of which affect the imaging fidelity. To avoid this issue, we apply a resonant push-out beam for 2 μs, apply 2D PGC for 30 ms, quasi-adiabatically ramp down the tweezer power to one-fifth of the full power, wait for 70 ms and then ramp up the power. After this sequence, we apply 2D PGC for 180 ms with an added bias magnetic field of 0.19 G. Note that this sequence for removing atoms in spurious traps was not fully optimized and we believe that this can be readily shortened in future work. In particular, the bias field during the 180-ms PGC segment could be more carefully optimized to reduce this time.

Single-atom imaging

For single-atom imaging in the optical tweezers, we use two pairs of PGC beams in a crossed-beam configuration (1/e2 diameter of 3.5 mm, 1.0 mW total). One pair is frequency-detuned relative to the other pair. Each PGC beam copropagates with a repumping beam (about 100 μW) and is independently steered. Auxiliary vertical PGC beams (not shown) aligned at a slight grazing angle along the objective axis are not used owing to high background reflections off the uncoated glass cell surface. During imaging, we increase the total intensity of the 2D PGC beams by about 3% and set the detuning to Δ = −15.5Γ from the bare atom |6S1/2, F = 4⟩ ↔ |6P3/2, F′ = 5⟩ resonant transition. We collect scattered photons for 80 ms on a qCMOS camera (Hamamatsu ORCA-Quest C15550-20UP), which we chose for its fast readout time and high resolution. The optical losses in the imaging system result in around 2.7% of scattered photons entering the camera, of which 44% are detected on the sensor owing to the quantum efficiency at 852 nm. The total magnification factor of the imaging system is 5.1.

The averaged point-spread function waist radius is measured to be 1.7 pixels on the qCMOS camera, corresponding to 7.8 μm on the camera plane or 1.5 μm on the atom plane. We estimate that, accounting for a finite atomic temperature (up to 50 μK in this simulation) and camera sensor discretization, the ideal point-spread function radius should be 1.25 pixels. We leave an investigation of the discrepancy to future work.

As well as the high fidelity and high survival demonstrated and characterized in Fig. 2 and Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5, we show in Extended Data Fig. 6 imaging results acquired with an imaging time of 20 ms. Notably, these imaging data were acquired with a PGC detuning of Δ = −9.5Γ. We measure an imaging fidelity and survival probability of 99.9571(4)% and 99.176(1)%, respectively.

Imaging model and characterization

We now describe the binarization procedure applied to each image acquired by the qCMOS camera. For each experimental run, typically consisting of a few hundred to a few thousand iterations, we apply this procedure anew.

We identify all sites by comparing the average image with the known optical tweezer array pattern generated by the SLM. The signal for each site and each image is obtained by weighting71 the number of photons per pixel with a function W(u, v) (Extended Data Fig. 4a). These weights are optimized by means of a quasi-Newton numerical method to maximize the imaging fidelity obtained with the model-free approach described below. This approach is agnostic of the photon distribution and relies on the consistency of the imaging outcomes. This helps guarantee that the imaging fidelity we quote is accurate and not artificially larger owing to overfitting.

We then compare the signal obtained for each site and each image with a threshold to determine whether an atom has been loaded. To position the threshold and estimate the fidelity, we use two complementary methods: an analytical model that predicts the shape of the imaging histogram by integrating the loss probability in a Poisson distribution and a model-free approach that estimates the fidelity by identifying anomalous atom detection results in three consecutive images. The first method infers classification errors from the shape of the photon histogram, whereas the second method detects errors directly; thus, the first method requires fewer samples to reach satisfactory accuracy. This first method is also compatible with any type of experimental runs, whereas the second method requires to specifically acquire three consecutive images. Hence, we use the first method to position the binarization threshold in most experimental runs, as well as for site-by-site analysis; we use the second method to accurately estimate the fidelity with a single array-wide threshold. The fidelities quoted in the main text are calculated using this second method.

We first describe the analytical model that predicts of the shape of histogram, which we call the ‘lossy Poisson model’. We fit six parameters: the initial filling fraction (before the first image) F, the mean number of photons collected from the background light λ0 and the atoms λ1, the broadening from an ideal Poisson distribution r0 and r1 and the pseudo-loss probability L. The exact meaning of all of these parameters is described below.

We first derive this model in the absence of broadening from an ideal Poisson distribution. We are interested in the photon distribution given that there is no atom at a given site at the beginning of imaging P(N = n|0) and the photon distribution given that there is an atom at this site at the beginning of imaging P(N = n|1), in which N is the number of photons collected. For the background photon distribution, we simply assume a Poisson distribution: \(P(N=n| 0)={{\rm{e}}}^{-{\lambda }_{0}}{\lambda }_{0}^{n}/n!\). For the atom photon distribution, we derive an expression by considering a loss-rate model in which each photon collection event (occurring with probability λ1dt) imparts a loss probability L/λ1. By integrating over t ∈ [0, 1], the system of equations that describes the evolution of the joint distribution of atom presence and photon count, we find the distribution given that one atom was initially present,

Here Γ represents the upper incomplete gamma function. The real loss probability during imaging is then given by \(\widetilde{L}=1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-L}\). This equation illustrates the two mechanisms that limit the imaging fidelity in experiments with single-atom imaging. The first mechanism, represented by the first term on the right-hand side of the equation, manifests as a Gaussian/Poissonian overlap between the two peaks of the photon distribution, reflecting our ability to record a substantial photon count above the imaging noise floor. Finite scattering rate, limited photon collection efficiency, background light leakage from the imaging beams or the ambient light and readout noise from the camera contribute to this limitation. The other mechanism that limits imaging fidelity is loss of atom during imaging. This manifests as a characteristic ‘bridge-like’ feature and is represented by the second term on the right-hand side of the above equation. The probability density in the bridge is small but finite across a wide range of photon counts between the two peaks of the imaging histogram72.

The overall photon probability distribution is then given by P(N = n) = FP(N = n|1) + (1 − F)P(N = n|0). For practical purposes, we empirically include a broadening of the Poisson distribution by writing P(N = n) = FP(N = n/r1|1)/r1 + (1 − F)P(N = n/r0|0)/r0 and by effectively considering non-integer photon numbers (by replacing factorials with the gamma function). For large n, this amounts to considering a Gaussian distribution for either of the two peaks but with the added benefit of including the loss through a physically motivated derivation using a Poisson process.

In this model, the true negative probability is given by \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{0}\,=\) \({\int }_{0}^{T}P(N=n| 0){\rm{d}}n\), in which T denotes the threshold, and the true positive probability is given by \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{1}={\int }_{T}^{\infty }P(N=n| 1){\rm{d}}n\). Finally, the imaging fidelity can be estimated as \({\mathcal{F}}=F{{\mathcal{F}}}_{1}+(1-F){{\mathcal{F}}}_{0}\) and the optimal threshold T can be found by maximizing the fidelity. We find that this model performs well when predicting the shape of the histogram site by site (Fig. 2a) but fails when the distribution of the background or atom photons in the array is non-Gaussian.

The second method we use to characterize imaging fidelity and survival requires no assumption for the photon distribution but considers that the imaging survival and fidelity is identical for three successive images46,73. We start by estimating the probability \({\widetilde{P}}_{{x}_{1}{x}_{2}{x}_{3}}\) of the presence of an atom in three images being x1x2x3, in which xi is a Boolean, equal to 1 if there is an atom and 0 if there is none,

Here S is the survival probability during imaging and F is the initial filling fraction. From this, we can estimate the probability of detecting y1y2y3 as \({P}_{{y}_{1}{y}_{2}{y}_{3}}={\sum }_{{x}_{1}{x}_{2}{x}_{3}}P({y}_{1}| {x}_{1})P({y}_{2}| {x}_{2})P({y}_{3}| {x}_{3}){\widetilde{P}}_{{x}_{1}{x}_{2}{x}_{3}}\). The conditional probabilities on the detection categorization given the true atomic presence are \(P(1| 1)={{\mathcal{F}}}_{1}\), \(P(0| 1)=1-{{\mathcal{F}}}_{1}\), \(P(1| 0)=1-{{\mathcal{F}}}_{0}\) and \(P(0| 0)={{\mathcal{F}}}_{0}\).

We use the method of least squares to minimize the difference between the experimental frequencies of bitstrings y1y2y3 and the \({P}_{{y}_{1}{y}_{2}{y}_{3}}\) by tuning the four parameters F, S, \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{0}\) and \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{1}\). The imaging fidelity is then defined as \({\mathcal{F}}=F{{\mathcal{F}}}_{1}+(1-F){{\mathcal{F}}}_{0}\). The array-wide binarization threshold is chosen to maximize the imaging fidelity (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Using this method, we find an imaging fidelity \({\mathcal{F}}=0.9999374(8)\), with a false-positive probability \(1-{{\mathcal{F}}}_{0}=7.01(8)\times 1{0}^{-5}\) and a false-negative probability \(1-{{\mathcal{F}}}_{1}=5.5(1)\times 1{0}^{-5}\); we find the survival to be S = 0.999864(2), slightly lower than the steady-state imaging survival probability measured by repeated imaging. Finally, we can inject the model-free survival probability into the lossy Poisson model to increase its accuracy (trying to extract the loss directly from the lossy Poisson model would indeed be inaccurate, because losses appear as a small tail feature between the two peaks of the imaging histogram). Using this approach, and fitting each site independently, we find an average imaging fidelity of 99.992(1)%, in reasonable agreement with the model-free imaging fidelity. By setting the atom loss to zero while keeping the other five fit parameters constant for each site, we can estimate a hypothetical imaging fidelity in the absence of atomic loss of 99.999(1)%. This analysis also illustrates that fitting the imaging histogram with a Gaussian or Poissonian model without including losses leads to overestimating imaging fidelities67.

Note that, for data shown in this work pertaining to loading and imaging, we use images 2–4 of a set of 16,000 iterations containing each four successive images, because we a posteriori realize that the survival probability and imaging fidelity are higher than for images 1–3. In this latter case, we measure an imaging fidelity of 0.999882(1) and survival of 0.999817(2). This could be because of remaining background vapour from the MOT loading stage or to imperfect background atom removal during the off-plane trapped atom push-out stage. To quantify the combined survival and fidelity in each of the images, we can use the conditional probability of observing one atom given that one atom was observed in the previous image, p(1|1). We find p(1|1) = 0.99963 between the first and second images, 0.99977 between the second and third images and 0.99981 between the third and fourth images. These numbers can still qualify as ‘high fidelity and high survival’. In principle, we could obtain the same fidelity and survival from the first image by waiting longer for the background vapour to diffuse in the chamber or by extending our push-out scheme.

In the context of atomic rearrangement, we expect that several rounds of imaging and rearrangement will be required to maximize the defect-free probability, as is already common in experiments with dozens or hundreds of atoms17,26. Hence, the lower fidelity and survival in the first image should not affect the final efficiency of rearrangement.

Qubit state preparation, control and readout

To initialize the tweezer-trapped atoms in the |6S1/2, F = 4, mF = 0⟩ ≡ |1⟩ state, we perform 5 ms of optical pumping on the 895-nm, F = 4 ↔ F′= 4 D1 transition. Simultaneously, we repump atoms in the F = 3 hyperfine ground state on the 852-nm, F = 3 ↔ F′ = 4 D2 transition. Both beams are coaligned and linearly polarized using a Glan–Thompson prism, parallel to the quantization axis defined by a 2.70-G bias magnetic field to drive π transitions. The beams are focused to dimensions 3.3 mm × 73 μm (1/e2 waists) at the tweezer array. Angular momentum selection rules forbid the \({m}_{F}=0\leftrightarrow {m}_{F}^{{\prime} }=0\) transition for ΔF = 0 and the atomic population accumulates in |1⟩ after several spontaneous emissions. We estimate a state preparation fidelity of 99.2(1)%, inferred from the early-time contrast of the Rabi oscillations in Fig. 4a. After preparing the atoms in |1⟩, the trap depth is adiabatically lowered to kB × 55 μK for microwave operation.

The set-up used to drive microwave transitions is described in Extended Data Fig. 7a. Similarly to other experiments74,75, the RF signal from an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG; Spectrum Instrumentation M4i.6622-x8) IQ-modulates a microwave signal generator (Stanford Research Systems SG386) set at a fixed frequency of 4.6 GHz. The signal is then frequency-doubled, filtered, passed through an isolator before being amplified to 10 W of microwave power (Qubig QDA). A 10-dBi-gain pyramidal horn emits the microwave field on the atom array at a distance of 15 cm.

For state readout, we apply a resonant |6S1/2, F = 4⟩ ↔ |6P3/2, F′ = 5⟩ pulse to push out atoms in |1⟩, before imaging the remaining atoms in |0⟩ with the scheme described above. By measuring the off-resonantly depumped population during push-out after pumping all atoms in |F = 4⟩, we infer a spin-resolved push-out fidelity of 99.88(5)%. The data in Figs. 4 and 5 and Extended Data Figs. 7, 8 and 10 are not corrected for state preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors. Instead, our measurements of the coherence time and gate fidelity rely on protocols that are intrinsically insensitive to SPAM errors.

Microwave spectroscopy reveals that the initial atomic population is close to an even distribution among the F = 4 sublevels. We measure a depumping rate of 0.064(5) μs−1 from F = 4 to F = 3 at our operating D1 optical pumping beam intensity when the D2 repump is shuttered off. The intensity of the D2 repump is increased until there is no measurable improvement in state preparation fidelity. Factors that limit the state preparation include imperfect linear polarization purity, spatial variations in the pump laser intensity owing to interference fringes arising from the surface of the science glass cell and heating incurred during the optical pumping. Modelling our magnetic field coils, we estimate that the local direction of the bias magnetic field deviates by <10−5 radians for distances of about 1 mm from the geometric centre, and this has a negligible impact on the state preparation of our large-scale array. Other state preparation schemes with higher fidelity have been demonstrated previously on smaller arrays and could be implemented in our system in the future22,76.

Characterizing the atomic qubits

To characterize the Rabi frequency across the array, we drive the qubit for variable times and measure the population in |1⟩, both at early times (0–150 μs) and at late times (900–1,000 μs). We observe a spatially varying Rabi frequency across the array (Extended Data Fig. 7b), with a gradient that is orthogonal to the propagation axis of the microwave field, which points to a reflection off a vertical metallic optical breadboard next to the vacuum cell.

We also characterize the dephasing in the array using Ramsey interferometry. During the free-evolution time, we detune the microwave drive field by δ = 2π × 1 kHz from the average qubit frequency. The envelope of the Rabi oscillation has a Gaussian decay with a characteristic time \({T}_{2}^{* }=14.0(1)\,{\rm{ms}}\). However, when considering each site individually, we find an average \(\langle {T}_{2}^{* ({\rm{site}})}\rangle =25.5\,{\rm{ms}}\) with a standard deviation of 3.2 ms (in the per-site case, we fit the oscillation decay with the dephasing decay function from ref. 77). This shows that dephasing across the array primarily occurs because of trap depth inhomogeneities (Extended Data Fig. 2d): assuming a Gaussian distribution of trap depth with standard deviation δU, the qubit frequencies in the array also follow a Gaussian distribution, which results in an ensemble-wide dephasing time \({T}_{2}^{* {\rm{(inh)}}}=\sqrt{2}\hbar /(\eta \delta U)\), in which η is the ratio of the scalar differential polarizability of the hyperfine ground states to their polarizability at the fine-structure level77. On the other hand, finite atomic temperature limits the per-site dephasing time \({T}_{2}^{* ({\rm{site}})}\). We observe an uneven distribution of \({T}_{2}^{* }\) across the atom array (Extended Data Fig. 8b), with a much lower \({T}_{2}^{* }\) measured for atoms trapped in tweezers at 1,055 nm than for those trapped in the bottom half of tweezers at 1,061 nm. This discrepancy could be because of worse optical aberrations in these areas that decrease the efficiency of polarization-gradient cooling or owing to different intensity noise profiles from the different fibre amplifiers or SLMs used on the two pathways. These data reveal that further investigation of noise sources specific to lasers or tweezer pathways could explain limiting factors on coherence times in neutral-atom arrays beyond those owing to photon scattering and dephasing processes44,78.

To relate \({T}_{2}^{* }\) and trap depth inhomogeneity or atomic temperature, the parameter η can be calculated as the ratio of the differential light shift of the hyperfine states to the electronic ground state light shift, which yields η = 1.50 × 10−4. (At the few-percent accuracy level, it becomes important to account for higher-order processes79,80, but such accuracy is not required here.) We corroborate this value by experimentally measuring the differential light shift by means of Ramsey interferometry at different depths (Extended Data Fig. 7c). We find η = 1.3(1) × 10−4, in reasonable agreement with the theoretical value. This allows us to estimate the atomic temperature during microwave operation as77 \(T=\sqrt{{{\rm{e}}}^{2/3}-1}\times 2\hbar /(\eta {k}_{{\rm{B}}}\langle {T}_{2}^{\ast ({\rm{s}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{e}})}\rangle )\approx 4.3\,{\rm{\mu }}{\rm{K}}\) (assuming that the temperature is sufficiently homogeneous to invert the fraction and the mean). This temperature may differ from the effective atomic temperature during other points of the experimental sequence that do not include the ramp-down and state preparation steps that may decrease and increase the temperature, respectively.

Dynamical decoupling

To extend the operation time of a realistic quantum processor well beyond the dephasing time of the array, we can apply dynamical decoupling on the atomic qubits. We empirically find that a period of 12.5 ms yields the longest dephasing time of 12.6(1) s for the reduced trap depth of kB × 55 μK. This timescale is a record for hyperfine qubit tweezer arrays5,6 and approaches results for a single hyperfine qubit in a customized blue-detuned trap81, alkali atoms in an optical lattice76 and nuclear qubits in a tweezer array82.

We vary the number of symmetric XY16 cycles and obtain the coherence contrast by applying a final π/2 pulse with phase 0 or π. Subtracting the population difference in these two cases yields the coherence contrast after the dynamical decoupling sequences.

We investigate in Extended Data Fig. 7g the coherence time T2 as a function of the trap depth for two different periods between π pulses (only for atoms trapped with the fibre amplifier at 1,061 nm), 12.5 ms and 6.2 ms. We attribute the different optimal periods at different depths to a trade-off between the unfiltered noise at a specific dynamical decoupling period83 and the effective depolarization induced by each π pulse. At the full trap depth, we measure a coherence time of 3.19(5) s, which still constitutes a record for hyperfine qubits in a tweezer array.

Considering the Raman scattering rate at a trap depth of kB × 0.18 mK, we expect that a substantially longer coherence time should be achievable. On the basis of this observation and the discrepancy in coherence time between atoms trapped at 1,061 nm and 1,055 nm seen in site-resolved data (Extended Data Fig. 8c), we posit that the observed coherence time is limited by intensity noise owing to the trapping lasers or the SLMs. We leave further investigation to future work.

Single-qubit gate randomized benchmarking

We measure our single-qubit gate fidelity through randomized benchmarking, similarly to refs. 84,85. For each given length n, we select Un−1,…, U0 at random from the 24 unitaries composing the Clifford group. We then apply U−1Un−1…U0, in which U−1 is the inverse of Un−1…U0. We decompose Clifford gates into elementary rotations around Bloch sphere axes using the zyz Euler angles. Rotations around z are implemented by offsetting the phase of all following x and y rotations86.

Owing to the inhomogeneous Rabi frequency, each rotation must be applied using length-error-resilient composite pulses. Among common families of error-resilient pulses50,87,88, we find that SCROFULOUS performs the best in our case. The SCROFULOUS implements a rotation of angle θ around the axis indexed by the angle ϕ on the Bloch sphere equatorial plane (abbreviated as θϕ) with a symmetric composite pulse \({({\theta }_{1})}_{{\phi }_{1}}{({\theta }_{2})}_{{\phi }_{2}}{({\theta }_{3})}_{{\phi }_{3}}\), in which θ1 = θ3 = arcsinc(2cos(θ/2)/π), \({\phi }_{1}={\phi }_{3}=\phi +\arccos \left(-\frac{{\rm{\pi }}\cos {\theta }_{1}}{2{\theta }_{1}\sin (\theta \,/\,2)}\right)\), θ2 = π and \({\phi }_{2}={\phi }_{1}-\arccos \left(-\frac{{\rm{\pi }}}{2{\theta }_{1}}\right)\). In our implementation, the average pulse area for a random Clifford unitary is 2.02π.

We fit the decay of the final population with the number of applied Clifford gates as \(\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}(1-{d}_{0}){(1-d)}^{n}\), in which d0 arises from SPAM errors, d is the average depolarization probability at each gate and n is the number of gates. The average Clifford gate fidelity is then given by49: Fc = 1 − d/2.

Even though the measured single-qubit gate fidelity is competitive with other state-of-the-art atom arrays experiments6,7,21,89, single-qubit gate fidelities >0.9999 have been reported85,90 in smaller arrays. Moreover, the maximal theoretical fidelity achievable for a given dephasing time is84\({\mathcal{F}}=\frac{3}{4}+\frac{1}{4{(1+0.95{(t/{T}_{2}^{* })}^{2})}^{3/2}}\), in which t is the average time needed to apply a Clifford gate, t = ⟨θ⟩/Ω, ⟨θ⟩ being the average pulse area per Clifford gate. Hence, gate fidelities higher than 0.99999 should be achievable based only on this value.

Beyond infidelities owing to decoherence, other parameters that may limit single-qubit gate fidelities are: (1) amplitude errors owing to instabilities in the microwave power; (2) phase errors owing to the microwave set-up; (3) phase errors owing to optical tweezer intensity noise; (4) phase errors owing to magnetic field noise. We are interested in which of these factors is limiting the gate fidelity. We rule out (1) because we observe that the Rabi frequency is very stable shot-to-shot (variations of less than 0.1%) and we estimate that such variations should be completely suppressed by the SCROFULOUS pulse. We also rule out (3), as reducing the trap depth further does not greatly improve the randomized benchmarking results (Extended Data Fig. 7g) and the fidelity is identical for atoms trapped in tweezers at 1,055 nm and 1,061 nm (unlike \({T}_{2}^{* }\) and T2). Although we cannot formally rule out (2), we estimate that it is unlikely because active components in the microwave set-up have a very low phase noise and we observe a sub-10 Hz linewidth of the microwave signal with a spectrum analyser.

We also notice a dominant phase noise at 60 Hz in the qubit array owing to the mains AC voltage. We measure the intensity of this noise with a spin-echo sequence, for which the time between each pulse is τ = 1/(2 × 60 Hz) (Extended Data Fig. 7e). Although this low-frequency noise cannot by itself explain the single-qubit gate fidelity loss, it points more generally to residual magnetic field noise that could be mitigated by shielding the vacuum cell, upgrading the current sources driving the magnetic field coils and/or by operating the MHz scale through Raman transitions. This can be achieved, for instance, by using the amplitude-modulation set-up used for Raman sideband spectroscopy.

Raman sideband spectroscopy with amplitude-modulation set-up

To measure the axial and radial trapping frequencies, we use a Raman set-up based on amplitude modulation of a laser beam91. The laser beam, red-detuned by 345 GHz from the D1 electronic transition in 133Cs, is phase-modulated using a resonant electro-optic modulator at 9.2 GHz (Qubig) before reflecting twice off a highly dispersive chirped Bragg grating (OptiGrate CBG-894-90) that transforms phase modulation into amplitude modulation. Two amplitude-modulated beams with different wavevectors k1 and k2 drive sideband transitions, similar to previous works with mode-locked lasers used to address the motion of trapped ions92,93. A schematic of the set-up is shown in Extended Data Fig. 9a.

In this configuration, the effective Lamb–Dicke parameter is \({\eta }_{\alpha }^{{\rm{LD}}}=| ({{\bf{k}}}_{1}-{{\bf{k}}}_{2})\cdot {\boldsymbol{\alpha }}| \sqrt{\frac{\hbar }{2m{\omega }_{\alpha }}}\), in which m represents the mass of caesium-133 and α denotes the radial or axial motion (with unit vector α). Out of 1 W of fibre-coupled amplitude-modulated laser light, each beam has 1–5 mW of laser power and a Gaussian 1/e2 diameter of about 2 mm. The sideband spectroscopy results are shown in Extended Data Fig. 9b,c, with radial and axial trapping frequencies measured to be, respectively, 29.30(4) kHz and 5.64(3) kHz. From this measurement, we infer a 1/e2 tweezer waist w0 = 1.17(6) μm. From the lineshape fit, we extract standard deviations across the array of 4.7 kHz and 1.9 kHz, respectively. Note that this measurement was done with atoms in the 1,061-nm tweezer array.

Atom transport

We create ten transport tweezers using 1,055-nm light through two AODs (Gooch & Housego AODF 4085), mounted in a crossed configuration and with an active aperture of about 15 mm diameter. We map the output after the pair of AODs to the back aperture of the objective using a telescope with 3:2 demagnification to match the same beam size at the back aperture of the objective as the beam from the SLM trapping tweezers.

The 1,055-nm light for transport is split from the same laser source that makes tweezers in the centre of the array (see Extended Data Fig. 2a). The 1,055-nm static and transport tweezers are then recombined with polarization and combined with 1,061-nm light with a polarizing beam splitting cube as well. These two pathways are not used concurrently for the long-distance coherent transport demonstration in Fig. 5 or in Extended Data Fig. 10b–d. We plan to switch in the near term to combining the 1,055-nm and 1,061-nm light using a dichroic mirror, such that we can use the power in the 1,055-nm path for both static and transport tweezers simultaneously without loss.

For the atomic movement, we use an adiabatic sine trajectory described by \(x=\frac{1}{{\rm{\pi }}}\sin ({\rm{\pi }}t)+t\,(t,x\in [-1,1])\). We find that we can execute a single move faster with the constant jerk trajectory5 (which we use for Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 4) but that the adiabatic sine trajectory incurs less heating: in the harmonic oscillator approximation, the increase in the average radial motional quanta ΔN for an adiabatic sine trajectory scales as \(\Delta N\propto \frac{{D}^{2}}{{\omega }^{5}{T}^{6}}\), in which D is the distance of the trajectory, T is the time of the trajectory and ω is the trap frequency. In the case of a constant jerk trajectory, \(\Delta N\propto \frac{{D}^{2}}{{\omega }^{3}{T}^{4}}\).

Note that, in the coherent transport data, the tweezer depth change along the trajectory is compensated with RF power, which we calibrate beforehand with static tweezers at each position. We believe that the transport fidelity can be further increased with more careful compensation of the trap depth including the AOD lensing effect in the future.

Randomized benchmarking of coherent transport

Coherent transport is achieved by suppressing dephasing during transport with dynamical decoupling. By evaluating the coherence contrast after 80 moves, we empirically find that the asymmetric XY4 sequence94 performs best (implemented using bare pulses). To perform interleaved randomized benchmarking53, we fix a total number of single-qubit gates N drawn from the Clifford group C1. We then interleave M (<N) total moves between the first M gates (atoms are held for roughly 54 μs between moves), after which we apply the remaining N − M gates to keep the total number of gates N constant and then apply the inverse of these gates. For the return probability data shown in Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 10a–d, we average over 72 sequences of random gates for each number of moves and apply N = 80 total random single-qubit Clifford gates. For the static and transported return probabilities, we apply the same single-qubit control sequence, including the XY4 dynamical decoupling. As in the case of randomized benchmarking, we use SCROFULOUS pulses for implementing the Clifford gates.

During each move of the benchmarking sequence, we apply XY4 in a transformed Clifford frame. Previous works have examined the interplay of dynamical decoupling and quantum operations by, for example, studying a system Hamiltonian in the ‘toggling frame’ induced by dynamical decoupling pulses95. Here we use related ideas but examine the decoupling operations in the frame rotated by the previously applied Clifford gates.

For instance, ignoring the Clifford gates between moves k − 1 and k, it is possible to concatenate two XY4 sequences X–Y–X–Y (with a symmetry operation) to obtain an XY8 sequence X–Y–X–Y–Y–X–Y–X that yields higher-order dephasing (and pulse-length error) suppression. However, the random Clifford gate Uk between the two sequences will cancel this effect by twirling the second XY4 sequence with respect to the first one. Thus, we can ‘counter-twirl’ the second XY4 sequence by applying it in a specific Clifford frame: the Pauli operator P becomes \({P}^{{\prime} }={U}_{k}^{\dagger }P{U}_{k}\). Up to a global phase, \({U}_{k}^{\dagger }X{U}_{k}\) and \({U}_{k}^{\dagger }Y{U}_{k}\) are two distinct elements of {X, Y, Z}, because Uk is a Clifford gate. If one of these two unitaries is Z, we further conjugate with a Hadamard gate H (or the equivalent basis change unitary between Y and Z) to map these two unitaries into X and Y or Y and X. This can easily be generalized to n-qubit Clifford gates. An example is the transport between the storage and interaction zone to apply a \({\mathcal{C}}{\mathcal{Z}}\) gate: because \({\mathcal{C}}{\mathcal{Z}}(X\otimes X){\mathcal{C}}{\mathcal{Z}}=-\,Y\otimes Y\), we can appropriately transform the decoupling sequence applied during the return move. This could also be extended to yield higher-order sequences, such as XY16. Notably, typical architectures for fault-tolerant quantum computation use almost exclusively Clifford gates96 (for example, past the initial generation of noisy magic-state inputs, all gates are Clifford). Therefore, this technique is fully applicable to fault-tolerant quantum computation.

At the end of the randomized benchmarking sequence, we measure both the atomic survival and the return probability (note that we apply a final π pulse to map the return state to the non-pushed-out state |0⟩). We fit the atomic survival to a clipped Boltzmann distribution Sn = 1 − exp(−1/(a + bn)), in which a and b are, respectively, the normalized initial temperature and normalized temperature accumulated per move. For the selected durations for interleaved randomized benchmarking, we find that a is negligible. We then fit the return probability to \((1-\exp (-1/bn))\cdot \left(\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}(1-{d}_{0}^{{\prime} }){(1-{d}^{{\prime} })}^{n}\right)\), in which d′ is the depolarizing probability for coherence, not accounting for atom loss. Owing to the randomized benchmarking procedure, coherence loss also includes the impact of XY4 dynamical decoupling, as it would not be necessary without transport. We then extract the instantaneous fidelity after n moves as \({F}_{n}=\left(1-\frac{{d}^{{\prime} }}{2}\right)\frac{1-\exp (-1/b(n+1))}{1-\exp (-1/bn)}\). Note that this is the most conservative approach and amounts to considering that the channel infidelity owing to losses is equal to the loss probability itself. In the context of fault-tolerant quantum computation, losses could be directly detected, leading to a higher tolerance to such errors than to Pauli errors. We could therefore assimilate loss to a depolarizing channel, which would substantially increase late-time instantaneous fidelities in Figs. 5 and 6 and Extended Data Fig. 10. It is worth noting that losses are subdominant for early-time IRB results presented in Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 10, therefore the quoted early-time fidelity in these figures is independent of the specific model we use for losses. To compute the 68% confidence interval, we bootstrap b and d′ using the fit results and covariance matrix. We corroborate the obtained fidelity with a simple exponential fit for the first few data points of the return probability, for which losses are negligible, and find similar early-time fidelities and error bars. We also notice that the shorter move of 270 μm has a slightly lower early-time instantaneous fidelity of 99.935(2)% compared with the 610-μm move (99.953(2)%). We believe that the discrepancy is probably because of a trap depth calibration imperfection and leave further investigation to future work.