Abstract

Glasses-free three-dimensional (3D) displays provide users with an immersive visual experience without the need of any wearable devices1,2. To achieve high-quality 3D imaging, a display should have both large linear dimensions and a wide viewing angle. However, the trade-off between spatial extent and bandwidth of optical systems, the space–bandwidth product, conventionally constrains the simultaneous maximization of the two. The two most common approaches to 3D displays are holographic3,4 and automultiscopic1,5,6, which, respectively, sacrifice either scale or viewing angle. Recently, some implementations enhanced by artificial intelligence have shown directions to mitigate these constraints, but they still operate within a set space–bandwidth product7,8. As a result, it remains challenging to fabricate large-scale wide-angle 3D displays9. Here we report the realization of a large-scale full-parallax 3D display with seamless viewing beyond 100°, maintained at over 50 Hz and 1,920 × 1,080 resolution on a low-cost light-field delivery setup. This device, called EyeReal, is realized by accurately modelling binocular view and combining it with a deep-learning real-time optimization, enabling the generation of optimal light-field outputs for each of the eyes. Our device could potentially enable applications in educational tools, 3D design and virtual reality10,11.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Delivering a three-dimensional (3D) sensation experience without additional wearable devices, known as glasses-free 3D or autostereoscopic display, can revolutionize human interaction with the digital world1,2,7. This aligns with the vision of the ‘ultimate display’11,12, in which light fields are reproduced at natural ranges with a wide viewing angle and large imaging size. Achieving this vision has been fundamentally constrained by the space–bandwidth product (SBP), a physical quantity that encapsulates the inherent coupling between spatial resolution and angular diversity in optical systems, and is ultimately bounded by the Lagrange invariant13.

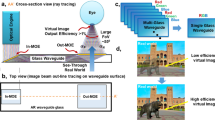

The development of autostereoscopic display technologies has highly progressed through two complementary paths, focusing either on compact, updatable holography3,7,14,15,16,17,18 or automultiscopic architectures with preset views1,5,6,19,20,21,22,23,24. The former enables precise light-field control but remains restricted to centimetre-scale displays (Fig. 1a). Conversely, automultiscopic displays scale to desktop dimensions but sacrifice continuity or adaptability beyond preset views (Fig. 1b,c). These approaches, alongside decades of exploration into diverse display technologies9, have advanced the state-of-the-art while exposing the intrinsic challenges posed by passive, limited SBP utilization. Recent efforts7,8,17,25 have extended these technologies through deep-learning-based algorithms, striving to mitigate architectural constraints and optimize display outcomes. However, these advances largely remain within existing frameworks and continue to rely on this static and partial use of available SBP. This intrinsic limitation shows a persistent inability to achieve both scalability and fidelity at once, forcing trade-offs across display size, viewing angle and parallax completeness. Although previous developments have advanced the field, these constraints underscore the need to rethink SBP utilization and explore new models for desirable autostereoscopic displays.

Each colour represents an effectual viewpoint. Considering that several models lack certain parallax types in other dimensions, we select the horizontal dimension for illustration. a, Holographic displays, representative of small-scale 3D displays, offer wide and continuous 3D viewing angles within a near-eye range because of extreme space compression. The display scale is limited to the square centimetre level and not suitable for natural human viewing, often requiring close, monocular observation. b, View-segmented automultiscopic models, with tailored optics, artificially scatter SBP into effectual viewpoint individuals on common display sizes. Each viewpoint is reused across segments, piecing together a broad but discrete viewing range. c, View-dense automultiscopic models prioritize realism by gathering scarce SBP into a fixed, farther viewing zone with local continuity. The trade-off is an extremely narrow, effectual imaging range, nearly immovable for the viewer. d, EyeReal revolutionizes SBP utilization by dynamically maximizing its use, precisely to where they are most needed at each moment, and transmits the limited optical information into the neighbourhood of eyes through real-time optimal light-field generation. Powered by the combination of physically accurate binocular modelling and artificial intelligence, EyeReal generically accommodates arbitrary, continuous viewing across an ultrawide range, requiring no customized optics.

Here we present EyeReal, the first proactive solution that, to our knowledge, optimally exploits the limited SBP in real time to achieve a desktop-monitor-scale full-parallax glasses-free 3D display with seamless ultrawide viewing ranges. Powered by a deep-learning engine that dynamically uses SBP around the eyes (Fig. 1d), EyeReal preserves a holography-level angular range while enlarging the display size by more than 103 times. The visual field extends well beyond 100° viewing and supports omnidirectional seamless imaging transitions, demonstrated through a prototype that can deliver real light-field outputs. This stems from the computational approach that combines physically accurate binocular modelling and artificial intelligence (AI) to enable real-time quality optimization around the eyes, whereas light-field hardware can serve as a platform for this effective and continuous SBP utilization. EyeReal delivers a full-parallax 3D experience, that is, stereo parallax, motion parallax and focal parallax, meeting all criteria for standard autostereoscopic displays26. The real-time light-field synthesis for any binocular viewing runs at more than 50 Hz with 1,920 × 1,080 spatial resolution on consumer-grade liquid-crystal display (LCD) stacks, eliminating the mandatory need for specialized optics such as spatial light modulators or lens arrays. This groundbreaking SBP-use exploration, realizing seamless, ultrawide large-scale 3D with low-cost hardware, lays a practical foundation for next-generation displays and unlocks transformative applications in digital entertainment, smart education, training and industrial design10,11,27.

Dynamic SBP utilization

We start with our paradigm shift in real light-field generation, which serves as the physical foundation for SBP-utilization maximization that accurately aggregates optimal information around the eyes over time. As established in Fourier optics, SBP describes the information capacity of an optical display system28 and is mathematically expressed as29

where A denotes area, δx and δy are the pixel dimensions, ux,max and uy,max are the bandwidth limits along the x-axis and y-axis in accordance with the Nyquist sampling theorem. For a system resolution of Nx × Ny and area Lx × Ly, this simplifies to S = NxNy. Considering the one-dimensional scenario, for a light field with maximum bandwidth umax and wavelength λ, the field of view (FOV) is given by30

High-resolution imaging indicates high spatial frequencies28, resulting in a tiny cross-sectional area of optical information flux, in turn, leading to a narrow viewing angle in 3D displays. For instance, a 24-inch 1,920 × 1,080 display with 2.1 million SBP yields a tiny FOV of about 0.1° × 0.1° at 532 nm green light wavelength. An entire light field with only 20 cm × 20 cm would require 565G SBP, far exceeding the limits of current display technologies, even with advanced light-emitting diodes (LEDs) capped at gigapixel resolutions31. Despite efforts32,33, progress to enlarge SBP remains minimal compared with its astronomical requirements, and recent studies34,35 still declare its inadequacy for practical applications.

Given this, to sustain the optimal use of inherently scarce SBP, we exploit the response interval of the human brain to perspective switching, optimizing the optical information flux around both eyes in real time. We proactively aggregate the limited, clearest region of a light field into the binocular centres together with their neighbourhoods at each timestamp. Accordingly, to adapt this strategy to arbitrary viewing directions over an extensive physical range, it requires the precise formulation of authentic stereo parallaxes in full spatial dimensions (horizontal, vertical and radial), aligned with binocular demands. The key lies in enabling optical aggregation to match the actual frustum field (the perspective viewing volume defined by the eye or virtual camera36; see schematic in Extended Data Fig. 1), rather than relying on idealized parallel-eye translation disparities commonly assumed in modern light-field displays5,8,25. This requires physically accurate binocular geometric modelling together with AI featuring robust, arbitrary generalization and real-time computation abilities, enabling light-field output adaptation for arbitrary binocular positions (see the Methods for more analysis and discussion).

In practice, under the actual viewing geometry, we establish both eyes as pinhole camera models oriented towards the light-field centre and parallel to the ground plane (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2). Six-dimensional (6D) pose matrices are then derived to establish the correspondences between the light field and the binocular imaging planes through the pinhole imaging and perspective transformation (Fig. 2d; see Methods and Supplementary Information for more geometry, computation and calibration details). This will serve as the physical modelling basis for the ocular geometric encoding for any binocular viewing. Through the physical simulation that conforms to biological principles, the light-field variations induce geometrically consistent binocular parallax, forming the computational basis for generating continuous motion parallax across an extensive spatial range.

a, Setup diagram for the real-world ocular modelling in light-field space. This setup follows the general principles governing how humans perceive objects located at the centre of the light field. b, The display prototype of EyeReal for a light-field delivery setup. It simply features a stacked array of liquid-crystal panels without additional tailored or complex optics. Each panel includes a colour filter, a liquid-crystal layer and a thin-film transistor. The entire stack with an RGB-D sensor is positioned between orthogonally oriented polarizers and illuminated by a white light source. For clarity, the in-device 3D content is shown separately. c, Optical modulation based on multilayer liquid-crystal phase control. The polarized light passes through multiple liquid-crystal layers, each introducing a pixel-specific phase computed by EyeReal. The final emitted intensity follows Malus’s law, enabling controlled light modulation in the ocular frustum. Here, we omitted the orthogonally oriented polarizers for simplicity. d, We reconstruct the spatial correspondence between human eyes and the light field under real-world viewing conditions. This enables precise characterization of binocular geometric information and extraction of the target visual imagery for display. e, The retinal images from eye camera imaging are decomposed into layered phase patterns by a lightweight fully convolutional network with multi-scale skip connections. Binocular poses are embedded using ocular geometric encoding. Trained with structured losses, the network outputs precise phase patterns and their frustum aggregation under Malus’s law yields the expected display results. Model of a rabbit created by Stanford University Computer Graphics Laboratory and adapted with permission.

Light-field generation

We adopted a light-field delivery setup as the display prototype (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1) for practical validation of the proposed SBP-utilization solution. Leveraging the formulation for real-time optimal light-field computation, EyeReal shifts the display functionality primarily onto the computational load of the algorithm, freeing the hardware from excessive burden. Its prototype requires only a multilayer light-field display structure that delivers realistic light fields aligned with natural perspective cues, without the need for additional complex or custom optical components. Here, we use the phase variation to encode the optical information within different depth regions of the light field, which is more optically efficient compared with intensity modulation because of its multiplicative attenuation22. Following Malus’s law (Fig. 2c), the luminous intensity I of the emitted light field, after backlighting the liquid-crystal stack positioned between polarizers, can be represented as

where dk denotes the nearest planar depth and Ft the current frustum field; l represents an emitted light ray in the frustum field, and I0(l) is the original intensity of l produced by the backlight through the rear polarizer; D is the set of all depth samples; and ϕd is the intersection phase of l and the optical pattern at depth d.

We develop the optimal light-field computation based on the binocular viewing as a learnable phase decomposition model with ocular geometric encoding (Fig. 2e). The retinal image through the crystalline lens is situated in the pixel coordinate system of the eye, which is not the most direct physical information for depth planes in the light-field coordinate system. The ocular geometric encoding introduces a reverse perspective transformation through the 6D ocular pose to uniform binocular images as geometrically normalized planar warpings (see mathematical details in the Supplementary Information), which facilitates the subsequent learnable decomposition by this geometric prior and embodies the system with a view-agnostic capability for dynamic display. Then we train a lightweight convolutional neural network to efficiently compute optical patterns based on the planar warpings, optimized by structured optical loss functions (Extended Data Fig. 3; see the Methods for more architecture, optimization and training details).

Experimental results

A desirable autostereoscopic display hinges on several essential perceptual attributes, including stereopsis (which naturally engages convergence), movement support and accommodation26. Among these, ideal movement support corresponds to continuous motion parallax, enabling seamless transitions for immersive 3D perception. We first assessed the ability of EyeReal to generate binocular parallax by acquiring multi-scale light-field datasets and evaluating the resulting autostereoscopic effects. For computer-generated content, we evaluated both object-level (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b) and scene-level (Fig. 3a) reconstructions. A comparable assessment on real-world captures covered similar scales, from everyday scenes (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 5a–d) to wide-area landmarks (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). The consistent high-quality binocular outputs across all scenarios indicate the effective parallax synthesis ability of EyeReal, unrestricted by specific viewpoints and positions. Beyond basic binocular synthesis, we assessed the ability of EyeReal to generate the full spatial range of stereo parallax dimensions necessary for perceptually complete 3D viewing. Whereas existing large-scale autostereoscopic solutions have to sacrifice certain parallax dimensions due to inherent SBP constraints, EyeReal sustains consistent output across motion directions and spatial trajectories. Under diverse multi-directional inputs, it exhibits highly stable, view-consistent predictions (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2), covering horizontal, vertical and radial dimensions. These outputs are generated in real time (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Video 4), enabling fluid motion adaptation across arbitrary spatial directions. The focal stack results under the same aperture (Fig. 3d) show that EyeReal supports focal parallax with depth-dependent presentation across different focal distances. The full-parallax support with real-time computational responsiveness suggests the suitability of the proposed AI-enabled dynamic SBP-utilization method for enabling glasses-free 3D displays under natural viewing conditions across broad spatial and content ranges.

a, Autostereoscopic results of a synthetic large-scale cityscape48. The magnified insets on the far right highlight specific binocular details. L, left eye; R, right eye. b, Autostereoscopic results of a real-world captured scene, a shoe rack with commonly placed household items on top49. c, Predicted views of a 3D object with hot dogs over all kinds (horizontal, vertical and radial) of spatial motion ranges. d, Focal results of a 3D scene with orchids50 under different depth focuses. e,f, Case-specific experimental validation of the physical device of autostereoscopic display. All photographic documentation was captured by a Sony α6300 mirrorless camera. Binocular viewing of a red car (e) captured at a specific time point (left) with perspective-indicating marks, and sequential display shots of this car (right) under varying spatial positions. The focal demonstration of this car (f), illustrating front focus (left) and rear focus (right) with depth-specific clarity in magnified insets.

a, Local-scale spatial performance comparison of EyeReal and modern view-segmented automultiscopy across binocular surroundings. b, Cross-scene and cross-pose generalization evaluation of EyeReal. It maintains robustness with high-quality rendering on previously unseen scenes and adaptability across a wide range of new head poses. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean with 6,000 samples. c, Global-scale spatial performance comparison of EyeReal and the iterative view-dense representative based on NTF with up to 50 iterations (iter.) across different visual-field ranges. NTF beyond 50 iterations was excluded because of speeds below 1 Hz (see e). Error bars show the standard deviation. d, Global-scale spatial performance comparison of EyeReal and the NVD representative8. As neural methods are trained on fixed views under predefined distances and directions, we compare multiple distance–direction combinations to highlight the differences. Error bars denote standard deviation. e, Runtime comparison of EyeReal, NTF and NVD within a sub-second-level timeframe. Except for the performance in b and c, EyeReal achieves real-time capability that is one to two orders of magnitude faster. f, Focal discrimination curves across uniformly sampled depths under the same aperture, from foreground to background. Each region shows smooth transitions in clarity with a peak at its corresponding depth. F–M region, a specific region between the foreground and midground; M–B region, a specific region between the midground and background. g, PSNR point-cloud heatmap across the visual field. Each point represents a randomly sampled viewpoint, with around 600,000 samples in total. Sampling at larger radial distances is omitted because of consistently high PSNR in those regions. PSNR, peak signal-to-noise ratio; SSIM, structural similarity index measure.

Beyond algorithmic simulations, the practical 3D display abilities of EyeReal were evaluated through a case-specific experimental validation, in which a concrete light field was reproduced using the display prototype (see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 7 for physical hardware setup). A comprehensive series of photographs was captured to characterize all aspects of the 3D display performance within a unified scenario, enabling a holistic assessment. The left and right eye views demonstrated discernible visual separation and clear structural delineation on the physical device (Fig. 3e, left, and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). For omnidirectional viewing, view consistency and fidelity remain stable under multi-dimensional spatial motions in the visual fields (Fig. 3e, right, and Supplementary Video 3). The physical focal evaluation showed clear depth selectivity, with front focus (Fig. 3f, left) sharpening proximal objects and blurring the background, whereas rear focus (Fig. 3f, right) brought distant elements into clarity while softening near ones. These results indicate that the display of EyeReal exhibits genuine focal discrimination (Supplementary Fig. 2) instead of depth-agnostic virtualization, helping to mitigate vergence-accommodation conflict (VAC)37,38, a common concern in extended reality. Moreover, we demonstrated real-time rendering of dynamic content (Supplementary Video 4), reflecting the superior speed enabled by AI-empowered computation and showcasing its promising application potential. These real-world demonstrations using merely consumer-grade components substantiate the theoretical advantages of EyeReal in physical practice and its feasibility for practical application.

Benchmarking

The inherent scarcity and passive use of SBP have confined modern glasses-free 3D displays to accommodating effectual viewpoints under specific controls, with these controls manifesting across multiple spatial granularity. Although small-scale solutions, such as holographic displays, seem impractical for real-world applications, this fundamental constraint persists in large-scale displays, regardless of whether adopting a view-segmented or view-dense automultiscopic choice. Achieving consistent performance across both locally and globally varying scales remains an important benchmark for enabling ideal, unrestricted 3D viewing. Modern view-segmented automultiscopy uses optical-path alterations with tailored flat panels, yielding multiple viewpoint-reused segments. This shared interval projection, as characteristic of flat-panel displays, marginally extends the viewing angle but introduces view inconsistency. In detail, each eye has only one effectual viewpoint within its tiny proximity, and other regions must approximate parallaxes through perspective transformations of that viewpoint. This approximation is observed to be highly limited (Fig. 4a left), with a high-quality range (<20 mm) even smaller than the eye diameter (approximately 25 mm). These displays with predefined viewing segments are prone to mismatches between the preset eye position of the system and the actual interpupillary distance (IPD), causing noticeable visual inconsistencies and distortion-induced discomfort39,40 (the large bluish area in Fig. 4a, left). Notably, this also explains why typical tracking-based directional displays41 suffer from the same issue, as their effectiveness is confined to the instantaneously tracked viewpoint rather than the broader neighbourhood of eyes, leaving them fragile to detection errors and natural eye movements. By contrast, by optimizing the light-field generation around the eyes, EyeReal ensures high-quality consistency and variable-motion tolerance over a wide area surrounding the eyes (Fig. 4a right), providing a robust foundation for immersive 3D viewing. EyeReal further remains robust on unseen scenes and new head poses, sustaining stable rendering quality across viewing variations (Fig. 4b).

Symmetrically, the view-dense model uses SBP in a fixed, narrow viewing zone, in which the effectual viewpoint densification ensures smoothness and realism within this confined area. This approximation relies on the overly idealized assumption of parallel eyes that simplifies binocular parallax to mere shifts but becomes highly challenged where parallax effects feature non-negligible rotational deformations, such as closer viewing distances or over-oblique directions. Existing approaches based on layered light-field displays with different computational techniques, including iterative-based view-dense (IVD) methods5,21,42 based on non-negative tensor factorization (NTF)43 and neural-based view-dense (NVD) advances8,25, fail to generalize beyond their specialized viewing scenarios (Fig. 4c,d), particularly in closer viewing ranges. By comparison, EyeReal, with precise physical modelling of any binocular viewing, demonstrates superior performance across all ranges of the visual field. This indicates that, without altering the optical design or introducing additional computational mechanisms compared with the above approaches, the observed advancements of EyeReal stem from the proposed effective use of SBP. Moreover, EyeReal achieves real-time runtime speed while maintaining high performance, yielding a speed improvement of one to two orders of magnitude in sub-second ranges compared with previous representatives (Fig. 4e). The average frame rate of the model plus binocular imaging without whistles and bells such as quantization and specialized-operator acceleration was found to be 50.2 frames per second. This combination of local-global consistency in high performance and low latency validates the effectiveness of the proposed SBP-utilization solution. Beyond the spatial performance characterized at both local and global scales, the depth perceptual continuity of EyeReal was further evaluated by measuring focal discrimination across various depths, which are not limited to the optical layer planes and showing smooth transitions with clear peaks at their corresponding focal depths (Fig. 4f). At a deeper level, we quantitatively any-view performance across the entire visual field (Fig. 4g) by randomly sampling extremely dense point clouds, emphasizing horizontal breadth, with vertical and radial dimensions analogous. The almost highlighted performance distribution indicates the computational ability of EyeReal for arbitrary viewpoints, numerically validating our SBP optimization solution with an ultrawide viewing angle well beyond 100° and seamless motion range that enables completely natural unrestricted content viewing in large display sizes.

Discussion

The methodology of EyeReal integrates physical principles with an AI-based mathematical model for dynamically optimal SBP utilization, using a neural network with ocular geometric encoding to compute the optimal light field around the eyes in real time. Although modern 3D display technologies are fundamentally constrained by limited optical capacity, hindering the concurrent expansion of image scale and viewing range, EyeReal maximizes the effective use of available optical information through continuous computational optimization, thereby enabling a practical coexistence of large imaging size and wide viewing angles within existing physical limits.

In pursuing wider viewing angles for glasses-free 3D experiences, prevailing solutions either rely on near-eye devices or adopt complex optical architectures within mainstream autostereoscopic systems. By contrast, EyeReal uses an AI-driven strategy in which wide-angle support is achieved computationally rather than through additional hardware complexity, enabling direct compatibility with conventional LCD panels and easing deployment on consumer-grade display and computing platforms. This offers a practical and cost-efficient pathway towards next-generation glasses-free 3D applications with both commercial and academic relevance. Notably, the reconstruction of real light fields of EyeReal with optimized quality around the eyes and focal parallax eliminates IPD mismatches and VAC, which are the two primary causes of discomfort in modern extended reality systems.

The SBP-utilization scheme developed by EyeReal offers a universal and effective scientific perspective. We believe that this model of dynamically optimal light-field presentation under limited SBP remains valid and scalable for achieving large-scale glasses-free 3D displays within the current optical system capability. Although EyeReal currently focuses on optimizing SBP utilization to conceptually validate a desirable glasses-free 3D display for individual binocular viewing, the methodology also holds the potential for multi-user adaptation by integrating techniques such as time multiplexing5,44 and directional backlighting1,45 to address associated challenges. Although the current-layered display prototype allows for viewing under ambient light conditions, integrating field sequential colour22,46 or mini-LEDs47 could further enhance optical efficiency and contrast for practical deployment. More broadly, the proposed SBP-utilization solution also shows promise for other light-field display technologies, such as updatable holography at large scales. This dynamic generation of optimal light fields ensures a balanced coexistence between a large imaging space, high spatial frequency across wide viewing angles and depth cue perception, despite all within the limited SBP availability.

The dynamic SBP-utilization solution in combination with physical principles and AI-enabled optical computation enables, to our knowledge, the first large-scale demonstration of a real-time 3D display with seamless ultrawide viewing range, opening an avenue for truly natural viewing glasses-free 3D displays.

Methods

SBP-utilization analysis

Owing to inherent SBP scarcity, existing 3D display approaches have been forced into static compromises, each emphasizing specific aspects at the expense of others in their display outcomes (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Information for more analysis and comparison details). Holographic displays, for instance, preserve complete 3D reconstruction by significantly compressing the displayed light field to centimetre-scale regions (about 1–2 cm2), ensuring wide-angle, high-quality optical content but becoming practically unscalable30. By contrast, automultiscopic displays maintain common display sizes (about 0.1–0.2 m2) more suitable for natural viewing scenarios but must limit their effectual viewing angles. Within this category, view-dense solutions use multilayer architectures to provide continuous and realistic optical generation at the cost of highly restricted viewing zones. Alternatively, view-segmented solutions achieve broad, horizontal viewing angles using single-panel optics21,23,51,52 to discretely spread out available SBP, sacrificing the stereo parallax across vertical and radial dimensions, as well as the focal parallax, although this loss of full parallax inevitably compromises immersion and visual comfort37,40.

Fundamentally, the limited practicality of these existing approaches arises from their passive use of scarce SBP, attempting to statically accommodate various viewing scenarios simultaneously. These static approximations inherently conflict with the extreme scarcity of SBP itself, and this remains unaltered even with AI enhancement (Supplementary Table 2). Recognizing this scientific constraint, it becomes clear that a proactive, dynamic use of limited SBP is necessary, that is, using optical resources precisely where they are most crucially needed at each moment. In practice, this means reconstructing accurate binocular light fields around target eye positions, as binocular parallax is the essential basis for human depth perception. Notably, this dynamic model does not rely on eye tracking to synthesize virtual disparities as is commonly done in conventional eye-tracked systems, as these systems respond only to instantaneous viewpoint positions, with responses typically exhibiting significant errors due to tracking noise and random eye movements. Instead, the rational and effective solution here requires the accurate and consistent generation of real physical light fields for both binocular viewpoints and their neighbourhoods, with eye tracking primarily serving to guide directional delivery rather than generating virtual content severely dependent on tracking precision. Although SBP, in principle, supports this localized generation, it remains challenging to precisely adapt optical output to arbitrary and extensive views within the neighbourhood of the eyes. To address this, we develop a physically accurate binocular geometric modelling and a deep-learning-based mathematical model that enable real-time computation of light-field outputs. To this end, EyeReal precisely adapts optical output to arbitrary binocular positions within an extensive viewing range, validated by a light-field delivery setup featuring large-scale imaging, wide-angle viewing and full-parallax attributes. This dynamic SBP-utilization strategy thereby realizes the possibility of achieving the long-desired glasses-free 3D display.

Eye camera modelling and calibration

Given an ocular position in the light-field coordinate system, we use the pinhole camera model (Supplementary Fig. 3) to simulate the retinal imaging process of the light field. In general, we align the centre of the screen with the centre of the light field where the object is located, and by default, the eye is directed towards the centre of the light field, which is the origin of the coordinate system. For standardization, we define the z-axis of the camera model to be opposite to the direction of sight. Moreover, to simulate normal viewing conditions, we stipulate that the x-axis of the camera is parallel to the ground on which the object is situated, consistent with the relative position of the observer and the object in the same world. Consequently, the y-axis of the eye camera is the normal to the plane formed by the z- and x-axes.

We initially get the relative ocular positions captured by the RGB-D camera. In the process of transferring eye positions into the light-field coordinate system, we first obtain their two-dimensional (2D) pixel coordinates by using a lightweight face detector. Combining the inherent camera intrinsic parameters and the detected pixel-level depth information, we can obtain the 3D coordinates of the eyes in the camera coordinate system. For one eye, this process can be formulated by

where ue and ve are the pixel-wise positions of the eye; (cx, cy) is the optical centre of the image, which represents the projection coordinates of the image plane centre in the camera coordinate system; fx and fy are the focal lengths of the camera in the x-axis and y-axis directions; and xc, yc and zc represent the transformed camera coordinates.

Then comes the alignment from the real-world eye coordinates to the digital light-field world. Given the fixed spatial configuration between the camera and the display setup, this alignment reduces to estimating a projection matrix \({M}_{{\rm{c}}}=[{A}_{{\rm{c}}}\,| {t}_{{\rm{c}}}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3\times 4}\), which transforms coordinates from the camera to the light field. Based on the characteristic of autostereoscopy, we design a simple and convenient calibration method based on the characteristic of reversible light paths (Extended Data Fig. 1). We select N calibration points in the light-field coordinate system, which also meet the visual field of the RGB-D camera. We replace the light-field images corresponding to the viewpoints with calibration marks (Supplementary Fig. 4) and provide them as input to the neural network to generate the corresponding layered patterns. Because the patterns can form only the best stereo effect at the input viewpoint, conversely, when the viewer sees the completely overlapping (the superposed colour is also the thickest at this time) rectangle with one eye at a certain angle on the screen of the hardware device, the current 3D eye camera coordinates \({c}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) captured by the camera and the world coordinates \({w}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) of the calibration points form an one-to-one correspondence. We solve for Mc using least squares regression (Supplementary Fig. 5) based on K pairs of corresponding calibration points

where \({c}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) and \({w}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) denote the ith calibration point in the camera and light-field coordinate systems, respectively. Once Mc is obtained, the eye position in the light-field coordinate system, Pe, is computed by homogeneous transformation

Eye–light-field correspondence

According to the geometric conventions of the above eye camera model, we can calculate the projection matrix Me = [Re|te] from the constructed eye camera coordinate system to the light-field coordinate system. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a, the centre of the screen is the origin O of the light-field coordinate system. For general cases, we assume that all the coordinate systems are right-handed and the ground plane is parallel to the xOy plane. We can get a pair of trivial vectors rz and rx along the z-axis and x-axis, respectively, based on their special position relation. In detail, the z-axis of the eye camera coordinate system is the OPe direction, and the x-axis is parallel to the xOy plane of the light-field coordinate system

The rotation matrix from the light-field coordinate system to the eye camera can be constructed from the unit vectors of these three trivial vectors as its column vectors

Here ∥⋅∥p denotes the ℓp vector norm applied to these trivial vectors. And the translation matrix is the vector of eye position

Then we project the light-field images corresponding to the binocular viewing onto each layer plane (Supplementary Fig. 6). Under the predefined FOV of the eye camera with a H × W pixel-size imaging plane, we can first derive the focal length fpix in pixel measurement

The screen planar positions \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{n}\,:= \,\{({x}_{i},{y}_{i},{z}_{i})\}{| }_{i=1}^{4}\) are hyperparametrized. For convenience, we define the dimension of depth to be parallel to some axis of the light field, which is the x-axis shown in Fig. 2b, so that we can determine xi by

where the index of pattern planes n ∈ {1, …, N}; dnear and dfar denote the nearest and farthest depth of the light field, respectively. We can determine the relative coordinates \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{n}^{{\prime} }\,:= \,\{({x}_{i}^{{\prime} },{y}_{i}^{{\prime} },{z}_{i}^{{\prime} })\}{| }_{i=1}^{4}\) at each eye camera corresponding to the four corner points of each pattern plane:

Based on equation (4), their pixel coordinates are calculated as

Here, we compensate for the minus sign for the opposite x-axis direction of two coordinate systems and let cx = W/2 and cy = H/2 for general cases. The 2D differences from the new corner coordinates \({{\mathbb{Q}}}_{n}^{{\prime} }\,:= \,\{({u}_{i}^{{\prime} },{v}_{i}^{{\prime} })\}{| }_{i=1}^{4}\) denote the imaging offsets compared with the original positions \({{\mathbb{Q}}}_{n}\,:= \,\{(0,0),(W,0),(W,H),(0,H)\}\). In this way, we can establish the equations of the eight unknowns of the perspective transformation based on these four corner pairs. The solved transformation matrix represents the 2D correspondences from the patterns to the eyes.

Neural network architecture

The ocular geometric encoding warps the view images from each eye camera onto multilayer screens based on binocular poses, establishing geometrically unified normalized projections. The network input is this set of normalized planar warpings at multilayer depths. Each warping represents the expectation of luminous intensity solely under a single viewpoint. The network decomposes into phase values at each depth through the expectation space of binocular views, which can be regarded as the inverse process of equation (3) during a single period. As the backlight source is uniformly illuminated, the light-field variation can be mapped to a finite integral of phases within a period. This makes its inverse decomposition equivalent to a differentiable hidden space by successively applying a set of learned 3 × 3 convolutional kernels, satisfying the fact that the pixel-level phase arrangement not only meets the expectation through a viewpoint but also is independent across the binocular viewpoints. The nonlinear activation used in the network (that is, rectified linear unit or ReLU) further filters out negative phase components through intermediate non-negative screening during the forward propagation.

For the specific design, the network is a fully convolutional architecture. It comprises an initial input layer, followed by five downsampling blocks and five corresponding upsampling blocks and concludes with a final output layer. Each block consists of two convolutional layers, all using uniform 3 × 3 convolution kernels. During downsampling, max pooling is applied to expand the receptive field, whereas bilinear interpolation is used in the upsampling stage to restore spatial resolution. To enable residual learning, skip connections are established between convolutional layers of matching spatial dimensions across the downsampling and upsampling paths. The input layer is configured to accept binocular RGB images, resulting in a six-channel input. To maintain computational efficiency, the number of channels at the input layer is set to 32, with the channel width increasing progressively in the downsampling layers according to the formula 32 × 2i, where i denotes the index of the downsampling block. By capitalizing on the swift advancements in graphics processing unit (GPU) computing, the neural architecture embedded with these lightweight elements can execute computations orders of magnitude faster.

Structured loss optimization

In spite of the proposed physics-based mathematical model, the optimization objectives of this AI model are supposed to be elaborated for the accurate light-field approximation. We divide the structured loss design into three parts for multi-faceted constraints. The basic loss function is used to gauge the consistency of the aggregated image formed by the superposition of light paths from each viewpoint based on the predicted hierarchical phase maps. Here, we model the data fidelity by ℓ1 norm, whose sparsity aids in recovering high-frequency phase details at the edges and contours of the light field, whereas its outlier insensitivity helps prevent overfitting to specific viewpoints53. In detail, we calculate the element-wise difference between the aggregated result \({I}^{{\prime} }\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{S}_{k}\times C}\) from the predicted patterns and the expected ocular light intensity \(I\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{S}_{k}\times C}\), where C means the RGB channel, and we use Sk for simplicity to denote the value of the emitted cross-sectional area Ft ∩ dk. The basic loss can be formulated as

where ∥⋅∥p denotes the ℓp vector norm applied on the pixel-wise luminous intensity vector \({\rho }^{{\prime} }\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{C}\) and its matching ground truth ρ.

The normalized planar warpings as inputs reflect only perspective light intensities from individual viewpoints, and merely enforcing intensity consistency with ground truth cannot effectively constrain the mutual exclusivity between the binocular views. View-specific information from one eye inevitably leaks into the other as noise, which can be mitigated through mutual-exclusion constraints. Following the structural assessment for image quality54, the second loss function physically considers the local contrast and structure of the emitted light field and sets their product as the whole mutual-exclusion measurement, which should be approximated to 1. This second loss \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{mutex}}}\) can be formulated by

which establishes a connection between the variances \({\sigma }_{{I}^{{\prime} }},{\sigma }_{I}\) and covariance \({\sigma }_{I{I}^{{\prime} }}\) of the aggregated result and the target image. Here, p and q represent the relative importance of contrast and structure, respectively. We make them both equal to 1, arguing that these two aspects should be considered equally. ξ is a systematic error that prevents the computation of 0. For simplicity, we assume ξ1 = 2ξ2 = ξ. By constraining the differences in the pixel distribution and fluctuation trends in local regions of both images, the phase approximation for the current viewpoint will be attentive to the noise artefacts coming from the other viewpoints and will smooth and erase them.

Owing to the periodicity of the light phase, there are infinitely many trivial but not generalized solutions in model training because of the possibility of falling into local optimal fitting. Therefore, in the early stage of model training, we calculate the frustum element-wise difference \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{lowfreq}}}\) from pure black patterns, which is the starting point of the first positive period, forcing the model to converge within the lowest frequency representation space, so that the phase diagram of layered patterns also conforms to the RGB distribution. The auxiliary loss function can be listed as

Here, Φd represents the total phase set of all light paths in the intersection area of the current frustum field Ft and the planar depth d. The auxiliary regularization term will be multiplied by a factor α that decays exponentially with training time as

where γ is the proportion of the current iteration to the total. This will be 0 at a preset earlier step for the complete elimination of suppression so that they will not be affected in the middle and late stages of model training convergence.

Ablation studies of these optimization components with visualizations are conducted to further understand how EyeReal functions in optical display and its underlying behaviours. The basic loss emphasizing basic intensity consistency proves crucial for maintaining fidelity, whereas the exclusivity measure loss enhances structural consistency by improving the noise resistance from the other viewpoint Extended Data Fig. 3a. Additionally, we visualized the ablation results of the low-frequency regularization loss Extended Data Fig. 3b, showinssg its effectiveness in guiding the network to focus on universal phase distributions rather than counterintuitive overfitting patterns. Further visualization of the network-computed phase patterns at various depths shows distinct depth-aligned highlights in each pattern Extended Data Fig. 3c. These attentive areas show that the neural network with structured optimization has accurately learnt an effective representation of local depth information, which is consistent with the physical depth structure of the light field.

Light-field dataset construction

A key requirement for a light-field dataset suitable for realistic viewing lies in the inclusion of stereo camera pairs captured from varying viewpoints while focusing on the same spatial point. However, these data characteristics are not directly available in existing public light-field datasets, as their multi-view data are limited to pixel-level difference, which fails to adequately simulate the way human eyes perceive scenes. To ensure the robust generalization and effectiveness of our learning-based mathematical model across diverse real-world viewing scenarios, we have meticulously developed a large-scale dataset characterized by complexity and diversity. For the generalization basis, the foundational component of our dataset focuses on capturing a broad spectrum of object geometries and appearances. We have incorporated a large assortment of geometrically rich and uncommon objects from uCO3D55 for its distinctive variety of object collections. We curated a collection of 3,000 diverse objects and generated 500 stereo image pairs per object, as the generalized priority is the number of scenes involving different objects rather than the number of viewpoints. This part serves as a robust basis for ensuring diversity in colour, texture and shape. To further enrich the complexity and scale of the dataset, we integrated the additional selected representative scenes from relevant studies48,49,50,56,57,58,59,60 and online resources, each comprising thousands of stereo image pairs. These supplemental scenes highly broaden the environmental complexity and spatial scales of the dataset, covering scenarios ranging from synthetic virtual environments to real-world captures. The scenes vary substantially in scale, encompassing intricate room-level interiors and expansive city-level landscapes. Moreover, they exhibit diverse lighting conditions and reflective materials, including indoor artificial illumination, outdoor natural lighting and scenarios with dim or subdued illumination. Experimental results validate that the model trained with this rigorously constructed dataset achieves remarkable generalization ability, including various unseen scenes and unknown head poses, maintaining inference speed and output quality without any notable compromise.

We develop a data preparation approach for light fields to achieve a more appropriate viewing simulation, and we use the polar coordinate system in 3D space to facilitate data configuration. For general cases, people stand facing the screen for viewing, ensuring that the line connecting their eyes remains parallel to the ground, thus perpendicular to the shorter side of the screen. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 2b, we define the screen-to-eye direction as the x-axis, sample multiple depth planes along this axis, and designate the horizontal and vertical axes as the y-axis and z-axis, respectively. We initiate a front viewpoint cloud shaped like a truncated frustum, in which each point signifies the midpoint between the eyes. The distance from the centre to each eye is denoted as R, the angle from the midpoint to the z-axis as φ and the angle to the y-axis as θ. Thus, assuming the interpupillary distance is d, we can derive the coordinates for each point in the Cartesian coordinate system as follows:

Owing to scenario-specific variations in dataset acquisition and inconsistencies in the spatial dimensions of light-field display subjects, both the scaling factor that maps the physical world to the digital light-field domain and the longitudinal thickness of the light-field volume exhibit significant variability. Specifically, we denote the scaling factor as s, which converts the physical screen width of the light field to its corresponding digital representation, and the physical depth extent of the light field as dthick, which varies with subject distance across scenes (Supplementary Table 3). Before this, we applied a compensation matrix Mcomp to each scene to standardize the orientation of the reconstructed light fields (Supplementary Table 4). This transformation realigns the originally unstructured coordinate systems such that the principal viewing axis of the target object consistently faces the positive x-direction.

Training and implementation details

The network was trained on our constructed light-field dataset using 32 NVIDIA Tesla A800 GPUs for 40 epochs. A learning rate warm-up strategy is used during the first epoch, followed by a cosine decay schedule for the remaining training period. The batch size is set to eight, comprising four object-level and four scene-level samples in each batch to preserve a balanced learning signal across both fine-grained and global spatial contexts. Given the relatively smaller size of the scene-level dataset, it is cyclically reused once fully traversed to ensure continued exposure and a balanced contribution to the optimization process.

To capture the diversity of real-world 3D structures and enhance the ability of the generalization of the model, we construct a training corpus that integrates both object-level and scene-level data under heterogeneous geometric and photometric conditions. Specifically, we randomly sample 3,000 object-level scenes from the uCO3D dataset and include 15 additional scene-level environments reconstructed from publicly available sources. The validation set comprises 150 unseen object-level instances and 2 unseen scene-level environments. For the training dataset, each object-level scene is rendered into 500 stereo image pairs from diverse, randomly sampled viewpoints. Each scene-level environment contributes 1,500 stereo pairs, resulting in a wide coverage of spatial configurations and view-dependent visual appearances. In the validation dataset, each object-level instance is rendered into 20 stereo pairs, whereas each scene-level environment contributes 1,500 pairs, yielding a total of 6,000 stereo images for evaluation.

For the ablation study, we curated a training set of 6,000 stereo pairs spanning 150 object-level instances with 20 pairs each and 6 scene-level environments with 500 pairs each. We trained three model variants, each using only the intensity loss, only the mutual-exclusion loss and a combination of both, and evaluated them quantitatively on the validation set. To evaluate generalizability, we constructed equivalent datasets from identical scenes but with perturbed head poses. Random perturbations of up to ±10° were applied independently across yaw, pitch and roll axes, introducing pose diversity to simulate realistic viewing variations. For global-scale spatial performance comparison, we constructed an image dataset with 3,000 pairs across multiple distance–orientation combinations. For the IVD benchmark, we sampled 1,400 pairs at 20 cm intervals from 10 cm to 150 cm. For the NVD benchmark, we categorized 1,600 pairs by viewing angles, including frontal and oblique perspectives and distances across four intervals spanning 30–130 cm. We designated 30–70 cm as the near range and 90–130 cm as the far range.

For human eyes, the part beyond 30° from the fixation point is called the peripheral vision, commonly known as the afterglow of the eye, which is actually the range that the human eye is insensitive. Therefore, when we build the eye camera model, we set its FOV to 40° to achieve a better sense of visual presence. We set φ ∈ [60°, 120°], θ ∈ [40°, 140°] and R ∈ [0.3, 1.5] in metres to adapt to the normal viewing situation. We use an efficient neural rendering approach59 to generate abundant training data from 3D targets. For the binocular localization part, we use the lightweight face detector61 built in OpenCV to obtain each eye position. The variation constant ξ of the mutual-exclusion loss that avoids system errors caused by denominators of zero is formulated as ξ = (kL)2, where k = 0.003 and L denotes the dynamic range of pixels, which is normalized as 1. The suppression cancellation time ratio of r in the low-frequency loss is set to 0.3. All experiments are evaluated on inputs with a resolution of 1,920 × 1,080 pixels, and we use a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 as the algorithm execution GPU for practical inference.

Hardware design of the display system

The display prototype for real-world demonstration (Extended Data Fig. 7) uses a BOE TFT-LCD with a resolution of 1,080 × 1,920 as the screen used for light-field display, and the pitch of one LCD pixel is 0.27 mm. The effective physical imaging area is 518.4 mm × 324 mm, and the actual physical size is 528 mm × 337.9 mm, with a manufacturing error of ±0.7 mm. We attached orthogonally oriented polarizing films to the front of the frontmost screen and the back of the rearmost screen to generate a polarized light field. The screen uses a white light source as the backlight source. The RGB-D camera we use is the Microsoft Xbox Kinect V2. Its colour camera has a resolution of 1,920 × 1,080, and the depth camera has a resolution of 512 × 424 with a depth measurement range of 0.5–4.5 m. For the hardware, we use acrylic plates 5 mm thick to fix and align each screen, and aluminium profiles as the load-bearing structure. The conceptual display for demonstration use N = 3 LCD screens with a 3-cm layered interval distance and transmit the imaging information using the HDMI (high-definition multimedia interface) interface protocol, run on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

Data availability

All data generated during this study, including the main results and the training/testing procedures, are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information. Figures were generated and processed using Python, Matplotlib, Microsoft PowerPoint and Adobe Photoshop. Our light-field dataset is available at GitHub (https://github.com/WeijieMax/EyeReal). Publicly available datasets or models were used for the following figures and supplementary materials: Fig. 2a, https://graphics.stanford.edu/data/3Dscanrep; Fig. 2b, https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:2494680; Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 3c and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2, https://www.fab.com/listings/4898e707-7855-404b-af0e-a505ee690e68; Fig. 3b, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1vh0mSl7v29yaGsxleadcj-LCZOE_WEWB; Fig. 3c, https://blendswap.com/blend/23962; Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 3b, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1cK3UDIJqKAAm7zyrxRYVFJ0BRMgrwhh4; Fig. 3e,f, Supplementary Videos 3 and 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6, https://blendswap.com/blend/17994; Extended Data Fig. 4a, https://blendswap.com/blend/23125; Extended Data Fig. 4b, https://blendswap.com/blend/8261; Extended Data Fig. 6a,d, https://github.com/Phog/DeepBlending; Extended Data Fig. 6b, https://www.tanksandtemples.org; and Extended Data Fig. 6c,https://github.com/google-research/multinerf.

Code availability

The computer code supporting the findings of this study is available at GitHub (https://github.com/WeijieMax/EyeReal). Code related to Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 3c and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2 is available at GitHub (https://github.com/city-super/MatrixCity).

References

Fattal, D. et al. A multi-directional backlight for a wide-angle, glasses-free three-dimensional display. Nature 495, 348–351 (2013).

Dodgson, N. A. 3D without the glasses. Nature 495, 316–317 (2013).

Tay, S. et al. An updatable holographic three-dimensional display. Nature 451, 694–698 (2008).

Shi, L., Huang, F.-C., Lopes, W., Matusik, W. & Luebke, D. Near-eye light field holographic rendering with spherical waves for wide field of view interactive 3d computer graphics. ACM Trans. Graph. 36, 236 (2017).

Wetzstein, G., Lanman, D., Hirsch, M. & Raskar, R. Tensor displays: compressive light field synthesis using multilayer displays with directional backlighting. ACM Trans. Graph. 31, 80 (2012).

Hua, J. et al. Foveated glasses-free 3D display with ultrawide field of view via a large-scale 2D-metagrating complex. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 213 (2021).

Shi, L., Li, B., Kim, C., Kellnhofer, P. & Matusik, W. Towards real-time photorealistic 3D holography with deep neural networks. Nature 591, 234–239 (2021).

Maruyama, K., Takahashi, K. & Fujii, T. Comparison of layer operations and optimization methods for light field display. IEEE Access 8, 38767–38775 (2020).

Holliman, N. S., Dodgson, N. A., Favalora, G. E. & Pockett, L. Three-dimensional displays: a review and applications analysis. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 57, 362–371 (2011).

Azuma, R. T. A survey of augmented reality. Presence 6, 355–385 (1997).

Gopakumar, M. et al. Full-colour 3D holographic augmented-reality displays with metasurface waveguides. Nature 629, 791–797 (2024).

Sutherland, I. E. The ultimate display. In Proc. IFIP Congress Vol. 2, 506–508 (SciSpace, 1965).

Greivenkamp, J. E. Field Guide to Geometrical Optics (SPIE, 2004).

Yu, H., Lee, K., Park, J. & Park, Y. Ultrahigh-definition dynamic 3D holographic display by active control of volume speckle fields. Nat. Photon. 11, 186–192 (2017).

Dorrah, A. H. et al. Light sheets for continuous-depth holography and three-dimensional volumetric displays. Nat. Photon. 17, 427–434 (2023).

Li, J., Smithwick, Q. & Chu, D. Holobricks: modular coarse integral holographic displays. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 57 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Liquid lens based holographic camera for real 3D scene hologram acquisition using end-to-end physical model-driven network. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 62 (2024).

Shigematsu, O., Naruse, M. & Horisaki, R. Computer-generated holography with ordinary display. Opt. Lett. 49, 1876–1879 (2024).

van Berkel, C. & Clarke, J. A. Characterization and optimization of 3D-LCD module design. In Proc. SPIE 3012, Stereoscopic Displays and Virtual Reality Systems IV 179–186 (SPIE, 1997).

Stern, A. & Javidi, B. Three-dimensional image sensing, visualization, and processing using integral imaging. Proc. IEEE 94, 591–607 (2006).

Lanman, D., Hirsch, M., Kim, Y. & Raskar, R. Content-adaptive parallax barriers: optimizing dual-layer 3D displays using low-rank light field factorization. In Proc. ACM SIGGRAPH Asia 2010 Papers Article No. 163, 1–10 (ACM, 2010).

Lanman, D., Wetzstein, G., Hirsch, M., Heidrich, W. & Raskar, R. Polarization fields: dynamic light field display using multi-layer LCDs. In Proc. 2011 SIGGRAPH Asia Conference Article No. 186, 1–10 (ACM, 2011).

Kawakita, M. et al. 3D image quality of 200-inch glasses-free 3D display system. In Proc. Stereoscopic Displays and Applications XXIII Vol. 8288, 63–70 (SPIE, 2012).

Wang, S. et al. Salience guided depth calibration for perceptually optimized compressive light field 3d display. In Proc. 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2031–2040 (IEEE, 2018).

Sun, Y., Li, Z., Wang, S. & Gao, W. Depth-assisted calibration on learning-based factorization for a compressive light field display. Opt. Express 31, 5399–5413 (2023).

Dodgson, N. A. Autostereoscopic 3D displays. Computer 38, 31–36 (2005).

Xiong, J., Hsiang, E.-L., He, Z., Zhan, T. & Wu, S.-T. Augmented reality and virtual reality displays: emerging technologies and future perspectives. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 216 (2021).

Goodman, J. W. Introduction to Fourier Optics (McGraw-Hill, 2005).

Lohmann, A. W., Dorsch, R. G., Mendlovic, D., Zalevsky, Z. & Ferreira, C. Space–bandwidth product of optical signals and systems. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 13, 470–473 (1996).

Park, J., Lee, K. & Park, Y. Ultrathin wide-angle large-area digital 3d holographic display using a non-periodic photon sieve. Nat. Commun. 10, 1304 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Micro-light-emitting diodes with quantum dots in display technology. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 83 (2020).

Li, G. et al. Space bandwidth product enhancement of holographic display using high-order diffraction guided by holographic optical element. Opt. Express 23, 33170–33183 (2015).

Li, J. et al. High space-bandwidth-product (SBP) hologram carriers toward photorealistic 3D holography. Laser Photon. Rev. 18, 2301173 (2024).

Lee, S., Jang, C., Moon, S., Cho, J. & Lee, B. Additive light field displays: realization of augmented reality with holographic optical elements. ACM Trans. Graph. 35, 60 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. High-fidelity light-field display with enhanced information utilization by modulating chrominance and luminance separately. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 78 (2025).

Kerlow, I. V. The Art of 3D Computer Animation and Effects (Wiley, 2009).

Hoffman, D. M., Girshick, A. R., Akeley, K. & Banks, M. S. Vergence–accommodation conflicts hinder visual performance and cause visual fatigue. J. Vis. 8, 33–33 (2008).

Matsuda, N., Fix, A. & Lanman, D. Focal surface displays. ACM Trans. Graph. 36, 86 (2017).

Wilcox, L. M. & Allison, R. S. Causes and consequences of IPD mismatch in XR devices. In Proc. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers Vol. 55, 182–185 (Wiley, 2024).

Kooi, F. L. & Toet, A. Visual comfort of binocular and 3D displays. Displays 25, 99–108 (2004).

Huang, T., Han, B., Zhang, X. & Liao, H. High-performance autostereoscopic display based on the lenticular tracking method. Opt. Express 27, 20421–20434 (2019).

Zhang, J., Fan, Z., Sun, D. & Liao, H. Unified mathematical model for multilayer-multiframe compressive light field displays using LCDs. IEEE Trans. Visual. Comput. Graph. 25, 1603–1614 (2018).

Cichocki, A., Zdunek, R. & Amari, S. Nonnegative matrix and tensor factorization [Lecture Notes]. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 25, 142–145 (2007).

Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Zheng, C., Surman, P. & Sun, X. W. Naked eye three-dimensional display system based on time-multiplexed technology. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 56, 604–607 (2025).

Borjigin, G. & Kakeya, H. Autostereoscopic display for multiviewers positioned at different distances using time-multiplexed layered directional backlight. Appl. Opt. 60, 3353–3357 (2021).

Chen, C.-H., Lin, F.-C., Hsu, Y.-T., Huang, Y.-P. & Shieh, H.-P. D. A field sequential color LCD based on color fields arrangement for color breakup and flicker reduction. J. Disp. Technol. 5, 34–39 (2009).

Zhu, L. et al. High-brightness hybrid compressive light field display with improved image quality. Opt. Lett. 48, 6172–6175 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Matrixcity: a large-scale city dataset for city-scale neural rendering and beyond. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 3205–3215 (IEEE, 2023).

Kerr, J., Kim, C. M., Goldberg, K., Kanazawa, A. & Tancik, M. LERF: language embedded radiance fields. In Proc. International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 19729–19739 (CVF, 2023).

Mildenhall, B. et al. NeRF: representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. In Proc. European Conference on Computer Vision (eds Vedaldi, A. et al.) Vol. 12346, 405–421 (Springer, 2020).

Wan, W. et al. Multiview holographic 3D dynamic display by combining a nano-grating patterned phase plate and LCD. Opt. Express 25, 1114–1122 (2017).

Nam, D. et al. Flat panel light-field 3-D display: concept, design, rendering, and calibration. Proc. IEEE 105, 876–891 (2017).

Zhao, H., Gallo, O., Frosio, I. & Kautz, J. Loss functions for image restoration with neural networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 3, 47–57 (2016).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Liu, X. et al. Uncommon objects in 3D. In Proc. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference 14102–14113 (2025).

Hedman, P. et al. Deep blending for free-viewpoint image-based rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 37, 257 (2018).

Knapitsch, A., Park, J., Zhou, Q.-Y. & Koltun, V. Tanks and temples: benchmarking large-scale scene reconstruction. ACM Trans. Graph. 36, 78 (2017).

Barron, J. T., Mildenhall, B., Verbin, D., Srinivasan, P. P. & Hedman, P. Mip-NeRF 360: unbounded anti-aliased neural radiance fields. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 5470–5479 (IEEE, 2022).

Kerbl, B., Kopanas, G., Leimkühler, T. & Drettakis, G. 3D Gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. ACM Trans. Graph 42, 139 (2023).

Irshad, M. Z. et al. NeO 360: neural fields for sparse view synthesis of outdoor scenes. In Proc. International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (CVF, 2023).

Wu, W., Peng, H. & Yu, S. Yunet: a tiny millisecond-level face detector. Mach. Intell. Res. 20, 656–665 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Chen for discussions and feedback; L. Xu, H. Wang and X. Sun for assistance with manuscript preparation; L. Jiang, B. Dai and Y. Li for help with partial dataset collection; K. Zheng, S. Rui and L. He for assistance with calibration and video shooting. This work was supported by the Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and partially funded by the College of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Fudan University. W.O. was supported by the JC STEM Lab of AI for Science and Engineering, funded by The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust and the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (project no. CUHK14213224). W.M. and Z.Z. conducted this work during their internship at the Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.M. and H.-S.Z. conceived the idea. W.M. designed specific system settings, established the whole framework, performed the experimental evaluations, formulated the hardware scheme, prepared the figures and wrote the paper. W.M., Z.Z. and C.Z. implemented the data preparation and conducted the experimental extensions. W.M., Z.Z. and H.-S.Z. built the display prototype. W.M. and H.-S.Z. conducted the calibration and capture of real-world visual demonstrations. W.O. and H.-S.Z. supervised the research. All authors discussed ideas and results and contributed to the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks YongKeun Park and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 The frustum-guided calibration design.

We leverage a frustum in 3D vision for calibration guidance, since it denotes the perspective viewing volume and describes the direction and extent of visible 3D space. Calibration is achieved when a precise alignment is observed, marked by the lines appearing darkest and thickest, indicating the ocular position aligns with the corresponding point in light-field space.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Detailed ocular geometry of our light-field setting.

a, Geometric relationship between the eye-camera and light-field coordinate systems, with the screen center O as the origin. The z-axis of the eye-camera system points to Pe, and its x-axis is parallel to the xOy plane of the light-field system. b, Geometric illustration of constructing the light-field dataset based on a. With a constant interpupillary distance, the eye positions are uniquely defined by the midpoint of their connecting line. A polar coordinate system is used to model natural viewing configurations, forming a truncated spherical-cone point cloud.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Physical interpretability and visualization of EyeReal.

a, b, Ablation study of EyeReal’s physics-based loss functions. a shows the contribution of each loss component. Error bars mean the standard deviation. b visualizes the phase pattern with (w/) and without (w/o) the application of Llowfreq. c, Visualization of computed layered phase patterns. The results reveal clear layer separation, with each layer concentrating depth information from its surrounding depth neighborhood.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Evaluation of EyeReal on additional computer-rendered scenes.

a, Autostereoscopic results of an indoor ficus tree with overlapping stems. b, Autostereoscopic results of an antique chair with layered armrests.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Evaluation of EyeReal on additional real-world captured scenes.

a, Autostereoscopic results of a computer desk in a child’s room alongside a bookshelf filled with vividly colored children’s books56. b, Autostereoscopic results of a truck parked on an outdoor street57. c, Autostereoscopic results of a toy dozer on a dining table with intricately textured placemats58. d, Autostereoscopic results of a room floor scattered with colorful educational toys and furniture56.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Evaluation of EyeReal on large-scale real-world captured scenes.

a, b, Autostereoscopic results of the Wukang Mansion and the China Art Museum, two iconic landmarks in Shanghai.

Extended Data Fig. 7 The physical device of autostereoscopic display prototype.

The white-light source is an LED array enclosed within the device, and orthogonal polarizer films are applied to on the front of the top screen and the back of the bottom screen in the LCD-panel stack.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text, Supplementary Figs. 1–6 and Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Supplementary Video 1

This video demonstrates stereo parallax photograph contrast on the practical display.

Supplementary Video 2

This video records real-time binocular stereo parallax on the practical display.

Supplementary Video 3

This video demonstrates seamless ultrawide viewing range in real time on the practical display.

Supplementary Video 4

This video records real-time rendering of dynamic content on the practical display.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, W., Zhao, Z., Zhao, C. et al. Glasses-free 3D display with ultrawide viewing range using deep learning. Nature 648, 76–83 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09752-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09752-y