Abstract

Three-dimensional atomic structure is routinely determined for periodic crystals. However, extending such analysis to amorphous materials remains a substantial challenge, despite the scientific and technological importance1,2. In this context, a recent report describing the three-dimensional structure determination of an amorphous solid using atomic-resolution electron tomography (AET) is truly remarkable3. If validated, such an analysis would be groundbreaking. Here we address this issue and investigate whether and when AET can identify all or most atoms in an amorphous nanoparticle. By simulating AET, we reveal limitations on the structural and chemical information AET can determine from noisy electron images. For monoatomic nanoparticles, the structure can be determined with an atomic-position accuracy of tens of picometres under stringent fluence, sampling and projection requirements. For multi-element amorphous nanoparticles, chemical identification resolution is determined by noise and experimental sampling. Heavier atoms are more easily resolved than lighter ones, and large chemical analysis uncertainties emerge when atomic peak and background intensities overlap. Using these insights, we delineate nanoparticle size, composition, electron fluence and image sampling requirements for AET. The results serve as a benchmark for future experiment design and demonstrate a viable approach for amorphous structure determination validation using AET.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The source data, including atomic models and simulated projection images, are available via Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/10850980 (ref. 34) upon publication.

Code availability

The codes supporting this study’s findings are publicly available from sources cited in relevant references. The ZMULT program, which we used to simulate HAADF STEM images, is available at https://github.com/rtbusch/AET_CodeModRepo upon publication.

References

Huang, P. Y. et al. Imaging atomic rearrangements in two-dimensional silica glass: watching silica’s dance. Science 342, 224–227 (2013).

Miao, J., Ercius, P. & Billinge, S. J. L. Atomic electron tomography: 3D structures without crystals. Science 353, aaf2157 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of an amorphous solid. Nature 592, 60–64 (2021).

Weyland, M. & Midgley, P. A. Electron tomography. Mater. Today 7, 32–40 (2004).

Scott, M. C. et al. Electron tomography at 2.4-ångström resolution. Nature 483, 444–447 (2012).

Bals, S., Goris, B., De Backer, A., Van Aert, S. & Van Tendeloo, G. Atomic resolution electron tomography. MRS Bull. 41, 525–530 (2016).

Crewe, A. V., Wall, J. & Langmore, J. Visibility of single atoms. Science 168, 1338–1340 (1970).

Treacy, M. M. J. Z dependence of electron scattering by single atoms into annular dark-field detectors. Microsc. Microanal. 17, 847–858 (2011).

Pennycook, S. J. & Boatner, L. A. Chemically sensitive structure-imaging with a scanning-transmission electron-microscope. Nature 336, 565–567 (1988).

Nellist, P. in Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (eds Pennycook S. & Nellist P.) Ch. 2 (Springer, 2011).

Borisevich, A. Y., Lupini, A. R. & Pennycook, S. J. Depth sectioning with the aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 3044–3048 (2006).

Xin, H. L. & Muller, D. A. Aberration-corrected ADF-STEM depth sectioning and prospects for reliable 3D imaging in S/TEM. J. Electron Microsc. 58, 157–165 (2009).

Gao, W., Sivaramakrishnan, S., Wen, J. & Zuo, J.-M. Direct observation of interfacial Au atoms on TiO2 in three dimensions. Nano Lett. 15, 2548–2554 (2015).

Collins, S. M. et al. Entropic comparison of atomic-resolution electron tomography of crystals and amorphous materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 166101 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. Three-dimensional atomic packing in amorphous solids with liquid-like structure. Nat. Mater. 21, 95–102 (2022).

Rogers, S. S., Waigh, T. A., Zhao, X. & Lu, J. R. Precise particle tracking against a complicated background: polynomial fitting with Gaussian weight. Phys. Biol. 4, 220 (2007).

Zhou, J., Yang, Y., Ercius, P. & Miao, J. Atomic electron tomography in three and four dimensions. MRS Bull. 45, 290–297 (2020).

Crowther, R. A., DeRosier, D. J. & Klug, A. The reconstruction of a three-dimensional structure from projections and its application to electron microscopy. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 317, 319–340 (1970).

Amali, A. & Rez, P. Theory of lattice resolution in high-angle annular dark-field images. Microsc. Microanal. 3, 28–46 (1997).

Ishizuka, K. A practical approach for STEM image simulation based on the FFT multislice method. Ultramicroscopy 90, 71–83 (2002).

Arslan, I., Tong, J. R. & Midgley, P. A. Reducing the missing wedge: high-resolution dual axis tomography of inorganic materials. Ultramicroscopy 106, 994–1000 (2006).

Hovden, R. et al. Breaking the Crowther limit: combining depth-sectioning and tilt tomography for high-resolution, wide-field 3D reconstructions. Ultramicroscopy 140, 26–31 (2014).

Yalisove, R., Sung, S. H., Ercius, P. & Hovden, R. Limits of three-dimensional resolution and dose for aberration-corrected electron tomography. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 014003 (2021).

Barkema, G. T. & Mousseau, N. High-quality continuous random networks. Phys. Rev. B 62, 4985–4990 (2000).

Rez, P. Virtual inelastic scattering in high-energy electron diffraction. Acta Crystallogr. A 34, 48–51 (1978).

Spence, J. C. H. & Zuo, J. M. Electron Microdiffraction (Plenum, 1992).

Cormack, A. M. Representation of a function by its line integrals, with some radiological applications. J. Appl. Phys. 34, 2722–2727 (1963).

Azzari, L. & Foi, A. Variance stabilization for noisy+estimate combination in iterative Poisson denoising. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 23, 1086–1090 (2016).

Dabov, K., Foi, A., Katkovnik, V. & Egiazarian, K. Image denoising by sparse 3-D transform-domain collaborative filtering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 16, 2080–2095 (2007).

van Aarle, W. et al. The ASTRA toolbox: a platform for advanced algorithm development in electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy 157, 35–47 (2015).

Pham, M., Yuan, Y., Rana, A., Osher, S. & Miao, J. Accurate real space iterative reconstruction (RESIRE) algorithm for tomography. Sci. Rep. 13, 5624 (2023).

Van Aert, S., Batenburg, K. J., Rossell, M. D., Erni, R. & Van Tendeloo, G. Three-dimensional atomic imaging of crystalline nanoparticles. Nature 470, 374–377 (2011).

Lee, J., Jeong, C. & Yang, Y. Single-atom level determination of 3-dimensional surface atomic structure via neural network-assisted atomic electron tomography. Nat. Commun. 12, 1962 (2021).

Busch, R. AET simulated images. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10850980 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering under award number DE-SC0024064. J.-M.Z. and R.B. acknowledge additional support from two NSF grants (DMR 2139185 and DMR 2226495) and Microscopy Australia at Monash University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-M.Z., P.R. and M.M.J.T. conceived of the idea, and J.-M.Z. directed the project. R.B. developed the tomographic reconstruction flow and conducted the simulation experiments and data analysis. M.M.J.T. provided the atomic models. J.-M.Z. developed the image simulation flow. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Robert Hovden, Jianwei (John) Miao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Extended data figures and tables

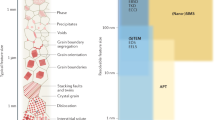

Extended Data Fig. 1 Impact of background noise on the reconstruction of a 208 atoms amorphous silicon nanoparticle.

Two examples of (a) without and (b) with the background are shown using simulated and reconstructed projection images and the reconstructed tomograms (in the form of iso-surfaces). The amount of background noise is equivalent to the Poisson noise of 1 electron. The incident fluence is 1.6 × 104 e/Å2.

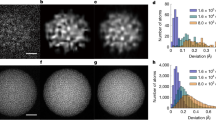

Extended Data Fig. 2 Simulation of the AET experiment reported by Yang et al.3 using the reported atomic structure and Co, Pd, and Pt as representative atoms.

(a) A simulated projection image (300 × 300 pixels) at the sampling of 0.33 Å/pixel and D = 5.6 × 104 e/Å2, using a 200 kV electron beam of 25 mrad convergence angle and a background noise of 1 e. The simulated images were centered using atoms at the surface extremities (Supplementary Note 1). (b) The preprocessed image of (a) with up-sampling of 3 times and noise smoothing, and (c) the corresponding projection obtained from the reconstructed tomogram using 55 projections from −70° to 70°. (b) The input atomic model with Pt, Pd, and Ni for the heavy, medium, and light atoms and plots showing three types of atoms separately. (c) The determined atomic structure from the simulated AET experiment as shown in the same way as (b). (d) The measured integrated atomic peak intensity histograms for three electron fluences. The atomic peaks were identified using a background threshold (1% of the maximum tomogram intensity). (e) The assignment of atomic types using the k-means clustering algorithm in ref. 3 and the CT obtained at D = 5.6 × 104 e/Å2. The low success rates for atomic identification are caused by the overlap of atomic peak intensities, which is also seen in the uploaded experimental data in ref. 3.

Extended Data Fig. 3 The impact of depth-of-focus on tomographic reconstruction.

(a) The simulated electron probe intensity distribution along the optical axis. (b) The simulated projection image and the CT in a 1 nm depth slice at the nanoparticle center. (c) The distribution of atomic peak intensity at the located atomic positions for the probe convergence angle of θ = 10 and 20 mrad, respectively. The nanoparticle simulated is 8 nm in diameter. The iso-surfaces in (b) are displayed at the value of 0.05 in normalized intensity. Further details are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Impact of the missing wedge on AET.

The panel shows the reconstructed tomograms for the missing wedge of 10°, 20°, and 30° and the rotation step size of 3° and 6°, respectively. The tomograms are displayed as the center slice of 1 nm thickness, looking down the rotation axis. All simulations were performed at the electron fluence of 1.6 × 105 e/Å2. The red sections in the illustrated diagrams on the right mark the missing wedges. The elongation of atoms is seen along the middle section of the missing wedge (the z direction).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Impact of depth section and random defocus on the reconstructed tomograms of an 8 nm amorphous Si nanoparticle.

(a) Depth sectioning, the projection image here is a sum of ten simulated images with 1 nm increment in focus at each rotation. (b) Random focus, a random focus is selected between 0 to 10 nm for the projection image at each rotation. An example of the simulated projection image after preprocessing is shown together with the reconstruction image and a 1 nm slice of the computed tomogram using the SIRT algorithm. The tomograms show the recovery of nearly uniform and isotropic peaks.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison between the simulated projection images with and without dynamical diffraction effect.

(a) A multislice simulation of a section of an 8 nm amorphous Si nanoparticle using the method described by Ishizuka (ref. 25), which is implemented in the ZMULT program (ref. 33). (b) The same section simulated using the projection approximation as described in the Method section. (c) The intensity profiles of the two simulations Taken along the marked lines in (a) and (b). The images in (a, b) are 32 pixels in height, each pixel is 0.195 Å.

Extended Data Fig. 7

Comparison between tomographic reconstructions using the SIRT and RESIRE algorithms for a 5 nm diameter amorphous silicon nanoparticle as shown in (a). The over-sampling ratio of 3 times is used for RESIRE reconstructions, while the input images are up-sampled by 3 times using interpolation for the SIRT reconstructions to match with the RESIRE algorithm. (b,c,d) The reconstructed tomograms using the SIRT and RESIRE algorithms are viewed along the z, x, and y axes. The tomograms appear nearly identical. The atomic identification yielded the same number of atoms, and the average deviation distance \(\overline{\Delta d}\) = 0.1 Å between the two reconstructions.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Notes 1–4 and Figs. 1–4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Busch, R., Rez, P., Treacy, M.M.J. et al. Limit of atomic-resolution-tomography reconstruction of amorphous nanoparticles. Nature 649, 1119–1122 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09924-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09924-w