Abstract

Anticipating future outcomes is a fundamental task of the brain1,2,3. This process requires learning the states of the world as well as the transitional relationships between those states. In rodents, the hippocampal spatial cognitive map is thought to be one such internal model4. However, evidence for predictive coding5,6 and reward sensitivity7,8,9,10 in the hippocampal neuronal representation suggests that its role extends beyond purely spatial representation. How this reward representation evolves over extended experience remains unclear. Here we track the evolution of the hippocampal reward representation over weeks as mice learn to solve a cognitively demanding reward-based task. We find several lines of evidence, both at the population and the single-cell level, indicating that the hippocampal representation becomes predictive of reward as the mouse learns the task over several weeks. Both the population-level encoding of reward and the proportion of reward-tuned neurons decrease with experience. At the same time, the representation of features that precede the reward increases with experience. By tracking reward-tuned neurons over time, we find that their activity gradually shifts from encoding the reward itself to representing preceding task features, indicating that experience drives a backward-shifted reorganization of neural activity to anticipate reward. We show that a temporal difference model of place fields11 recapitulates these results. Our findings underscore the dynamic nature of hippocampal representations, and highlight their role in learning through the prediction of future outcomes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The complete dataset for all experiments is available at McGill University Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/877CGZ). The dataset should not be used for republication without prior consent from the authors.

Code availability

All source codes used in the current study are available on request to the corresponding authors.

References

Schultz, W., Dayan, P. & Montague, P. R. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275, 1593–1599 (1997).

Keller, G. B. & Mrsic-Flogel, T. D. Predictive processing: a canonical cortical computation. Neuron 100, 424–435 (2018).

Schultz, W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 80, 1–27 (1998).

O’Keefe, J. & Nadel, L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map (Clarendon Press, 1978).

Stachenfeld, K. L., Botvinick, M. M. & Gershman, S. J. The hippocampus as a predictive map. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1643–1653 (2017).

Levenstein, D., Efremov, A., Eyono, R. H., Peyrache, A. & Richards, B. Sequential predictive learning is a unifying theory for hippocampal representation and replay. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.28.591528 (2024).

Sosa, M. & Giocomo, L. M. Navigating for reward. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 472–487 (2021).

Lee, I., Griffin, A. L., Zilli, E. A., Eichenbaum, H. & Hasselmo, M. E. Gradual translocation of spatial correlates of neuronal firing in the hippocampus toward prospective reward locations. Neuron 51, 639–650 (2006).

Aoki, Y., Igata, H., Ikegaya, Y. & Sasaki, T. The integration of goal-directed signals onto spatial maps of hippocampal place cells. Cell Rep. 27, 1516–1527 (2019).

Gauthier, J. L. & Tank, D. W. A dedicated population for reward coding in the hippocampus. Neuron 99, 179–193 (2018).

Kumar, M. G., Bordelon, B., Zavatone-Veth, J. A. & Pehlevan, C. A model of place field reorganization during reward maximization. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 267, 31892–31929 (2025).

O’Keefe, J. & Dostrovsky, J. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 34, 171–175 (1971).

Deshmukh, S. S. & Knierim, J. J. Influence of local objects on hippocampal representations: landmark vectors and memory. Hippocampus 23, 253–267 (2013).

Kraus, B. J., Robinson, R. J. 2nd, White, J. A., Eichenbaum, H. & Hasselmo, M. E. Hippocampal ‘time cells’: time versus path integration. Neuron 78, 1090–1101 (2013).

Aronov, D., Nevers, R. & Tank, D. W. Mapping of a non-spatial dimension by the hippocampal-entorhinal circuit. Nature 543, 719–722 (2017).

Sosa, M., Plitt, M. H. & Giocomo, L. M. A flexible hippocampal population code for experience relative to reward. Nat. Neurosci. 28, 1497–1509 (2025).

Kaufman, A. M., Geiller, T. & Losonczy, A. A role for the locus coeruleus in hippocampal CA1 place cell reorganization during spatial reward learning. Neuron 105, 1018–1026 (2020).

Dupret, D., O’Neill, J., Pleydell-Bouverie, B. & Csicsvari, J. The reorganization and reactivation of hippocampal maps predict spatial memory performance. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 995–1002 (2010).

Lee, S.-H. et al. Neural signals related to outcome evaluation are stronger in CA1 than CA3. Front. Neural Circuits 11, 40 (2017).

Lisman, J. & Redish, A. D. Prediction, sequences and the hippocampus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1193–1201 (2009).

Aharoni, D. & Hoogland, T. M. Circuit investigations with open-source miniaturized microscopes: past, present and future. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13, 141 (2019).

Pnevmatikakis, E. A. & Giovannucci, A. NoRMCorre: an online algorithm for piecewise rigid motion correction of calcium imaging data. J. Neurosci. Methods 291, 83–94 (2017).

Zhou, P. et al. Efficient and accurate extraction of in vivo calcium signals from microendoscopic video data. eLife 7, e28728 (2018).

Mosser, C.-A. et al. The McGill-Mouse-Miniscope platform: a standardized approach for high-throughput imaging of neuronal dynamics during behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 20, e12686 (2021).

Bussey, T. J. et al. New translational assays for preclinical modelling of cognition in schizophrenia: the touchscreen testing method for mice and rats. Neuropharmacology 62, 1191–1203 (2012).

Schneider, S., Lee, J. H. & Mathis, M. W. Learnable latent embeddings for joint behavioural and neural analysis. Nature 617, 360–368 (2023).

Xu, H., Baracskay, P., O’Neill, J. & Csicsvari, J. Assembly responses of hippocampal CA1 place cells predict learned behavior in goal-directed spatial tasks on the radial eight-arm maze. Neuron 101, 119–132.e4 (2019).

Mehta, M. R., Barnes, C. A. & McNaughton, B. L. Experience-dependent, asymmetric expansion of hippocampal place fields. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 8918–8921 (1997).

Berke, J. D. What does dopamine mean?. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 787–793 (2018).

Glimcher, P. W. Understanding dopamine and reinforcement learning: the dopamine reward prediction error hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15647–15654 (2011).

Watabe-Uchida, M., Eshel, N. & Uchida, N. Neural circuitry of reward prediction error. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 40, 373–394 (2017).

Dayan, P. Improving generalization for temporal difference learning: the successor representation. Neural Comput. 5, 613–624 (1993).

Gershman, S. J., Moore, C. D., Todd, M. T., Norman, K. A. & Sederberg, P. B. The successor representation and temporal context. Neural Comput. 24, 1553–1568 (2012).

Maes, E. J. P. et al. Causal evidence supporting the proposal that dopamine transients function as temporal difference prediction errors. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 176–178 (2020).

Kim, H. R. et al. A unified framework for dopamine signals across timescales. Cell 183, 1600–1616 (2020).

Lisman, J. E. & Grace, A. A. The hippocampal-VTA loop: controlling the entry of information into long-term memory. Neuron 46, 703–713 (2005).

Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction (MIT Press, 1998).

Amo, R. et al. A gradual temporal shift of dopamine responses mirrors the progression of temporal difference error in machine learning. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 1082–1092 (2022).

Foster, D. J., Morris, R. G. & Dayan, P. A model of hippocampally dependent navigation, using the temporal difference learning rule. Hippocampus 10, 1–16 (2000).

Kumar, M. G., Tan, C., Libedinsky, C., Yen, S.-C. & Tan, A. Y.-Y. One-shot learning of paired association navigation with biologically plausible schemas. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.03580 (2021).

Fang, C. & Stachenfeld, K. L. Predictive auxiliary objectives in deep RL mimic learning in the brain. In The 12 International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2024).

Lillicrap, T. P., Cownden, D., Tweed, D. B. & Akerman, C. J. Random synaptic feedback weights support error backpropagation for deep learning. Nat. Commun. 7, 13276 (2016).

Miconi, T. Biologically plausible learning in recurrent neural networks reproduces neural dynamics observed during cognitive tasks. eLife 6, e20899 (2017).

Murray, J. M. Local online learning in recurrent networks with random feedback. eLife 8, e43299 (2019).

Nøkland, A. Direct feedback alignment provides learning in deep neural networks. In Proc. 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 1045–1053 (NIPS, 2016).

Overwiening, J., Kumar, M. G. & Sompolinsky, H. TeDFA-δ: Temporal integration in deep spiking networks trained with feedback alignment improves policy learning. In 8th Annual Conference on Cognitive Computational Neuroscience (CCM, 2025).

Heath, C. J., Phillips, B. U., Bussey, T. J. & Saksida, L. M. Measuring motivation and reward-related decision making in the rodent operant touchscreen system. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 74, 8.34.1–8.34.20 (2016).

Kim, C. H. et al. Trial-unique, delayed nonmatching-to-location (TUNL) touchscreen testing for mice: sensitivity to dorsal hippocampal dysfunction. Psychopharmacology 232, 3935–3945 (2015).

Friedrich, J., Zhou, P. & Paninski, L. Fast online deconvolution of calcium imaging data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005423 (2017).

Lauer, J. et al. Multi-animal pose estimation, identification and tracking with DeepLabCut. Nat. Methods 19, 496–504 (2022).

Pnevmatikakis, E. A. et al. Simultaneous denoising, deconvolution, and demixing of calcium imaging data. Neuron 89, 285–299 (2016).

Sheintuch, L. et al. Tracking the same neurons across multiple days in Ca2+ imaging data. Cell Rep. 21, 1102–1115 (2017).

Yang, W. et al. Simultaneous multi-plane imaging of neural circuits. Neuron 89, 269–284 (2016).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International Conference on Machine Learning 1597–1607 (PMLR, 2020).

Kraskov, A., Stogbauer, H. & Grassberger, P. Estimating mutual information. Phys. Rev. E 69, 066138 (2004).

Ross, B. C. Mutual information between discrete and continuous data sets. PLoS ONE 9, e87357 (2014).

Markus, E. J., Barnes, C. A., McNaughton, B. L., Gladden, V. L. & Skaggs, W. E. Spatial information content and reliability of hippocampal CA1 neurons: effects of visual input. Hippocampus 4, 410–421 (1994).

Floresco, S. B., Todd, C. L. & Grace, A. A. Glutamatergic afferents from the hippocampus to the nucleus accumbens regulate activity of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 21, 4915–4922 (2001).

Barnstedt, O., Mocellin, P. & Remy, S. A hippocampus-accumbens code guides goal-directed appetitive behavior. Nat. Commun. 15, 3196 (2024).

Kalivas, P. W., Churchill, L. & Klitenick, M. A. GABA and enkephalin projection from the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum to the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience 57, 1047–1060 (1993).

Ibrahim, K. M. et al. Dorsal hippocampus to nucleus accumbens projections drive reinforcement via activation of accumbal dynorphin neurons. Nat. Commun. 15, 750 (2024).

Russo, S. J. & Nestler, E. J. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 609–625 (2013).

Kumar, M. G., Tan, C., Libedinsky, C., Yen, S.-C. & Tan, A. Y. Y. A nonlinear hidden layer enables actor-critic agents to learn multiple paired association navigation. Cereb. Cortex 32, 3917–3936 (2022).

Krishnan, S., Heer, C., Cherian, C. & Sheffield, M. E. J. Reward expectation extinction restructures and degrades CA1 spatial maps through loss of a dopaminergic reward proximity signal. Nat. Commun. 13, 6662 (2022).

Bordelon, B. & Pehlevan, C. Self-consistent dynamical field theory of kernel evolution in wide neural networks. J. Stat. Mech. 2023, 114009 (2023).

Vyas, N. et al. Feature-learning networks are consistent across widths at realistic scales. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 1036–1060 (2023).

Paninski, L. & Cunningham, J. P. Neural data science: accelerating the experiment-analysis-theory cycle in large-scale neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 50, 232–241 (2018).

Jazayeri, M. & Ostojic, S. Interpreting neural computations by examining intrinsic and embedding dimensionality of neural activity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 70, 113–120 (2021).

Urai, A. E. et al. Large-scale neural recordings call for new insights to link brain and behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 11–19 (2022).

Yu, B. M. et al. Gaussian-process factor analysis for low-dimensional single-trial analysis of neural population activity. J. Neurophysiol. 102, 614–635 (2009)

Hollup, S. A. Molden, S, Donnett, J. G., Moser, M. B. & Moser,E. I. Accumulation of hippocampal place fields at the goal location in an annular watermaze task. J. Neurosci. 21, 1635–1644 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the M.P.B. laboratory for discussions and for providing inputs during the analysis of the data; in particular, Z. Ajabi and J. Q. Lee. We thank M. Iordanova, B. Richards, E. J. P. Maes, J. Quinn Lee, H. Nagaraj, Z. Haqqee and A. Sharma for comments on the first draft of this manuscript, and A. Peyrache and B. Richards for their guidance on data analysis. M.G.K. and C.P. were supported by an NSF award (DMS-2134157). C.P. was also supported by an NSF CAREER award (IIS-2239780), a Sloan Research Fellowship and the William F. Milton Fund from Harvard University. This work was made possible in part by a gift from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Foundation to establish the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence. This work was also supported by funding from Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS) postdoctoral fellowships awarded to A.N.-P. and C.-A.M.; CIHR project grants 463403 and 480510 to M.P.B.; and a Core Facilities and Technology Development grant from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, ‘Health Brains for Health Lives’, to S.W. and M.P.B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y., A.N.-P., S.W. and M.P.B. conceptualized the project. A.N.-P. performed surgeries and recordings. M.Y. organized the raw data and did the preprocessing, analysis, modelling and data visualization. M.Y., T.G. and É.W. did the preprocessing of the data. M.G.K. developed the model and ran the simulations. M.G.K. and M.Y. analysed the simulated data. C.P. supervised the modelling section. M.Y., M.G.K. and C.-A.M. wrote the initial draft. M.Y., M.G.K., C.-A.M., C.P., S.W. and M.P.B. contributed to editing and revising the first draft of the paper. M.P.B. guided and supervised all stages of experiments and data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 a, Sample footprints for each of the mice and learning-curve analysis.

a, Footprints of an example session for each mouse are presented. The number inside each panel represents the average number of detected cells across sessions for that mouse. b, Learning curves for all seven mice are presented. Performance is defined as the proportion of correct trials. The shades of blue colour show different delays from lighter to darker being 2, 4, and 6 s. c, Mouse performance averaged across mice (n = 7 mice) for the first day and last day of each delay is presented. d, Number of recording days for each of the mice. e, The number of days that it takes for each mouse to reach the learning criteria (two consecutive days of performance > 0.7) for different delays (n = 7 mice). f, The average learning curve across mice is plotted for those sessions with 2, 4, and 6 s delay. Each point represents the mean performance across mice, and error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Because mice completed different numbers of sessions, data were back-anchored (i.e., aligned to each mouse’s final session) before averaging. Only time points with data from at least 4 mice were included in the final average. The total number of mice for each session is plotted in the inset of each panel. Total number of sessions across all mice for 2 s delay: 54 sessions; 4 s delay: 35; and 6 s delays: 30. Bar graphs and error bars in c,e show mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial encoding in CA1.

a, Place fields of three representative cells (left column) and their corresponding vector fields (right column). b, Distribution of the size of the place fields of identified place cells is plotted. The average place-field size is ~3.88 cm (see Extended Data Fig. 3). c, Naive Bayes (NB)67 position decoding shows an accurate position decoding from raw calcium traces. All registered cells in each session are used to train the NB model. d, Distribution of decoding error across frames of 24 sessions of Mouse #5 shows a heavy-tailed distribution. The dashed line shows the mean decoding error: ~4.14 cm. e, Decoding error (averaged within each session) over time (mouse #5). Each point represents the average decoding error across frames in a session, with error bars indicating the 95% confidence interval of the lower and upper bounds of the decoding error distribution. The inset shows the correlation between decoding error and time (session) across mice (n = 7 mice). Bar graphs and error bars in the inset show mean ± s.e.m. For the inset: two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test against zero: 0.3750. f, Comparing decoding error for correct and incorrect trials for three phases of Sample, Delay, and Choice. Note that from sample to choice, the points are shifted above the diagonal, indicating a higher decoding error for incorrect trials. Bar graphs and error bars in the insets show mean ± s.e.m. (n = 24 sessions, mouse #5). g, The decoding analysis suggests that incorrect trials are associated with higher decoding errors as we approach the choice. Each point represents one session of mouse #5 (no. of sessions = 24). Bar graphs and error bars show mean ± s.e.m. P-values of two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test against zero: P-value (sample) = 0.5633, P-value (delay) = 0.3944, P-value (choice) = 0.0163. h, Same analysis as f across mice (n = 7). Each point in h represents one mouse. P-values of two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test against zero: P-value (sample) = 0.5781, P-value (delay) = 0.0469, P-value (choice) = 0.0156. Bar graphs and error bars show mean ± s.e.m. i, The salient moments of the task are colour-coded (the moments of touching the screen, reward approach, and reward consumption). Each point is a frame. j, CEBRA embedding26 of neuronal traces reveals distinct neuronal state spaces for task phase68,69. (Colour coding is the same as in i). k–r, Spatial decoding error is higher in incorrect trials despite controlling for behavioural differences. k–m, Comparison of behavioural metrics between correct and incorrect trials displayed by blue and orange, respectively. Incorrect trials are associated with longer latency times (the time between choice initiation and choice is selection) (k, two-sided t-test p-value: 9.8715e-10), greater distance travelled during the choice phase (l, two-sided t-test p-value: 3.0604e-12), and lower average running speed (m, two-sided t-test p-value: 0.0070522). n, Spatial decoding error using a Naive Bayes decoder is significantly higher during incorrect trials, suggesting impaired spatial representation. Two-sided t-test p-value: 6.4021e-06 (for k–m, n = 2,567 correct trials, and 1,395 incorrect trials). o–r, The same decoding analysis is repeated after subsampling trials to match the joint distribution of latency, distance travelled, and average speed between correct and incorrect trials. Two-sided t-test p-value for o: 0.98826, p: 0.75216, q: 0.91907. Even after this behavioural matching, decoding error displayed in r remains higher for incorrect trials, indicating that degraded spatial encoding during incorrect trials cannot be solely explained by differences in behavioural variables. Two-sided t-test p-value: 8.8521e-05. Bar graphs and error bars in the inset of k–r show mean ± s.e.m. For o–r, n = 1,183 correct trials, and 1,183 incorrect trials.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Place-field analysis.

a, Spatial rate map of ten representative place cells are plotted. For each cell the left panel is the raw rate map and the right panel is the masked rate map (masking has been done by turning all bins with value less than 90% percentile to zero). Place cells are identified if their spatial information content exceeds 99% percentile of distribution of spatial information content for 1,000 shuffled cases. b, Distribution of spatial information content for place cells and non-place cells. Non-place cells: n = 1,519, 2,494, 1,979, 2,228, 4,706, 267, 175. Place cells: n = 1,003, 2,715, 2,661, 1,469, 4,270, 261, 201. Bar graphs and error bars show mean ± std. c, Percentage of identified place cells across mice. In average 47.5 ± 2.5 % of the cells were identified as place cells (n = 11, 11, 11, 7, 24, 23, 13 sessions for mice 1 to 7, respectively). Bar graphs and error bars in b,c show mean ± s.e.m. d, We calculated averaged place cell’s field sizes for a various amount of masking threshold from 75% to 95% percentile. After doing visual inspection we decided to use 90% percentile for masking spatial rate maps to calculate the size of the place field. This choice of threshold led to average place cell’s field size = 3.6 cm. n = 12580 cells. Error bar shows 95% confidence interval for each side of place-field size distribution. e, The correlation between the percentage of place cells with time (session) across mice is calculated. Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test against zero: 0.6875. Bar graph and error bar show mean ± s.e.m. We do not observe a consistent trend across mice. f, Spatial rate maps and vectorized rate maps of eight representative cells are plotted. The vectorized rate maps clearly demonstrate the modulation of neuronal activity by the mouse’s behaviour, specifically its heading direction. g, Two dominant stereotyped behaviours in this task are the mouse running from the reward area to touch either the right or left screen and then running back to the reward port. A distinct population of neurons encodes different phases of each of these behaviours. Here, we visualize 10 place cells encoding different phases of the mouse running from the reward port to the right screen and then running back to the reward port. Tuning curves include spatial rate maps and heading direction tuning curves. h, The sequences of cells for flattened stereotyped behaviours of running to the left and right are plotted. Neuronal responses are obtained by averaging across trials within a representative session. Distinct subpopulations of neurons support each of these two behaviours, remaining silent during the other movement. i, GPFA dimensionality reduction70 on the entire population for these two patterns of behaviour reveals perpendicular neuronal trajectories in the neuronal latent space. j, Sample spatial rate maps for 5 representative cells are plotted. k, Scatter plot of peak rate maps. Each point represents the position of the peak activity of spatial rate map for one cell. l, Density plot of the scatter plots shown in k. m, Reward over-representation score for all the sessions of mouse #5 are calculated. The score is measured based on the overall representation shown in l. It is defined as the average of 10% spatial bins closest to reward normalized by the average of all bins. n, Reward over-representation across all mice is plotted. Each point shows one session. Consistent with previous studies18,71, our analysis of spatial coding reveals an over-representation of the reward area once the mouse has learned the reward location (n = 11, 11, 11, 7, 24, 23, 13 sessions for mice 1 to 7, respectively). Bar graphs and error bars in b,c show mean ± s.e.m.

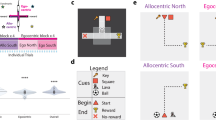

Extended Data Fig. 4 Distinct neuronal sequences cover the choice to reward interval for left and right trials.

a, Schematic showing different trial types and phases of the task (choice and reward). b, For each session, the three cell types of interest, screen cells, reward-approach cells, and reward cells, are concatenated. Neurons are divided into two groups, population 1 and population 2, based on their responses to each trial type. Neurons with higher averaged peak activity during left trials are assigned to population 1, while those with higher averaged peak activity during right trials are assigned to population 2. Within each population, cells are sorted by the timing of their peak activity. The white dashed line indicates the choice time, and the black dashed line marks the onset of the reward. The time between choice and reward is scaled to one second. c, Task vs ITI neuronal responses for different cell types are plotted. The neuronal activity (averaged deconvolved calcium traces) for each of the cell types during the task vs ITI is plotted. For all cell types, there is a significant difference between task and ITI moments, demonstrating the task-related engagement of these cells. This is not observed for other cells (cells that are not identified as any of the three cell types). Top row: each point is one cell, and we have combined all sessions of one mouse (mouse #5) (n = 1,152 reward cells, 562 reward-approach cells, 686 screen cells, and 6,781 other cells). Bar graph and error bar in the insets show mean ± s.e.m. Bottom row: averaged across all cells for each mouse; each point represents the mean activity for one of the mice (n = 7 mice). The error bars on the points show s.e.m. Bar graph and error bar in the insets show mean ± s.e.m. In d–i, we show results for decoding task-related contextual features while conditioning on space. d, Task phase decoding (sample vs choice) during left screen contact (n = 181 sessions). Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test P-value = 9.4979e-10. e, Task phase decoding (sample vs choice) during right-screen contact (n = 168 sessions). Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test P-value = 4.3287e-13. f, Decoding correctness during left screen sample contact (n = 132 sessions). Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test P-value = 0.0220. g, Decoding correctness during right-screen sample contact (n = 118 sessions). Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test P-value = 0.0083. h, Decoding correctness during left screen choice contact (n = 131 sessions). Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test P-value = 1.1285e-07. i, Decoding correctness during right-screen choice contact (n = 118 sessions). Two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test P-value = 3.2030e-06. Bar graphs and error bars in the bottom row of d–i show mean ± s.e.m. Each point represents one session. The illustrations in a,d–i were created using Affinity Designer.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Methods for measuring population- and single-cell-level responses.

a, Top, embedding of neuronal traces into 32-dimensional CEBRA space. For all our latent space analyses, the dimensionality of the latent space is 32. Bottom, binary time series, indicating reward consumption moments with reward frames set to 1 and all other frames set to 0 (the same analysis is applied to the screen and reward approach). b, Latent representation of neuronal activity; blue points represent frames during reward consumption, grey points represent other frames. c, Average of calcium activity across all cells averaged across trials (mean ± s.e.m, averaged across trials). d, Mouse speed prior to the reward and during reward consumption. e, Fivefold cross-validation is used to decode the reward moments from latent representation of neuronal activity. For each fold, a linear classification model is trained on the other four folds to predict the reward in the held-out data. MI between true and predicted reward, averaged across 5 folds, represents the information content of the reward representation for each recording session. f, The shuffle-control procedure is used to identify reward cells. It involves calculating the neuronal activity during reward consumption (averaging the deconvolved trace) for each neuron and comparing it with the distribution of neuronal activity from 1,000 random circular shuffled traces. A neuron is classified as a reward cell if its neuronal activity surpasses the 99th percentile of the distribution of shuffled neuronal activity (bottom left panel). The bottom right panel shows the distribution of neuronal activity for all reward cells (black) and compares them with their corresponding shuffled ones (blue) (n = 6,495) (see ‘Identification of cell types’ in Methods). Right panel shows the percentage of identified reward cells across mice. The numbers above each box show the cross-session average number of reward cells for each mouse. The dashed grey line and the shade around it represent the average number of reward cells ± s.e.m. (8.5 ± 1.5%). Chance level is 1%. g, The same shuffle-control procedure as described in f is used here to identify screen cells. Neuronal activity 150 ms before and after the screen poke is used to assess neuronal activity at the screen. The panel at the bottom right compares shuffle and control neural activity across all screen cells recorded across sessions and mice. The right panel shows the percentage of identified screen cells across mice. Each point represents one session, and the numbers above each box show the cross-session average number of reward cells for each mouse. h, Same analysis as for f,g but for reward-approach cells. Cells are identified as reward-approach cells if their activity from the screen to the reward onset is greater than chance. Box plots in f–h show median (centre line), 25th–75th percentiles (box), and range within 1.5 × IQR (whiskers); points beyond whiskers are outliers. The illustrations in f–h were created using Affinity Designer.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison of AUC- and deconvolution-based measures of neuronal encoding for different cell types.

a–c, Each panel plots encoding scores derived from the AUC method (y axis) against those derived from deconvolved calcium traces (x-axis), for reward cells (a), reward-approach cells (b) and screen cells (c). Across all comparisons, we observe a strong correlation between the two methods, indicating consistency in the estimation of encoding score (n = 1025 reward cells, 558 reward-approach cells, and 674 screen cells). The inset in each panel shows R2 across all mice (n = 7 mice). Bar graph and error bar in inset of a–c show mean ± s.e.m. d–g, Temporal dynamics of percentage of reward-encoding cells using AUC-based analysis. d,e, Using an AUC-based cell identification method, we quantified the percentage of neurons encoding reward and examined their relationship with session number (day) (d) and behavioural performance (e). f, Correlation analyses across all mice (n = 7 mice) show that the percentage of reward cells is negatively correlated with session number and only weakly correlated with performance. g, Results from our linear model further support this observation, demonstrating that the evolution of reward-cell recruitment is better explained by session number rather than performance—consistent with findings presented in the main manuscript using averaged activity obtained using deconvolved traces (n = 7 mice). Bar graphs and error bars in f,g show mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Task difficulty and behaviour variability do not drive the reduction in reward representation over sessions (days).

a, The percentage of reward cells across sessions is shown. Grey points represent all sessions, while black points indicate sessions with a 2-second delay. Both groups exhibit a negative correlation over time. b, The percentage of reward cells is plotted against task performance. In both groups, the correlation is weak. c, Correlation values for both groups, across all mice (n = 7 mice), are shown. The data reveal a strong negative correlation between the percentage of reward cells and session number, and a weaker correlation with performance in both conditions. d–f, The same analysis as in a–c is applied to reward information content (f: n = 7). The results similarly show a negative correlation between reward MI and session number, and no significant correlation with performance. These patterns are consistent across both groups: the full dataset and the subset of sessions with a 2-second delay. g–n show that the slight variability of mice’s behaviour across sessions does not drive the reduction in reward representation over time. g, The percentage of reward cells is negatively correlated with session number. h, There is a weak correlation between the percentage of reward cells and the time interval between choice and reward. The time between choice and reward is used as a behavioural measure that quantifies how fast the mouse approaches the reward after poking the screen and selecting the correct choice. i, Correlation values across all mice (n = 7 mice) confirm a strong negative correlation of percentage of reward cells with session number and a weak correlation with behaviour. j, Modelling results indicate that session number explains a greater proportion of variance than latency time (n = 7 mice). k–n, The same analysis as in g–j is repeated for reward MI instead of the percentage of reward cells. These results similarly show that reward MI decreases over sessions and is weakly influenced by behaviour (m,n: n = 7 mouse). Bar graphs and error bars in inset of c,f,i,j,m,n show mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Reward magnitude modulates the response amplitude of reward-approach neurons.

a, Schematic of a mouse running towards reward (bigger reward) versus incentive (smaller reward). b, Two example neurons showing stronger response when the mouse is running towards the reward (blue) vs incentive (red). c, Two example neurons showing similar responses when the mouse is running towards reward (blue) vs incentive (reward). In the bottom row of b,c, the solid line and shaded area show mean and s.e.m., respectively. d, The average calcium activity across reward-approach neurons is higher when the mouse (this example mouse #5) is approaching the reward compared to the incentive. Each point represents one recording session (n = 24 sessions). e, Similar analysis as d across mice. Each point is obtained by averaging across seven sessions (n = 7 mice). Bar graphs and error bars in d,e show mean ± s.e.m. The schematic in a was created using Affinity Designer.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Cell tracking across sessions.

a, Panels i–iv show the spatial footprints of different cell types in a representative session. bi, A zoomed-in view of a reward cell, with the green contour outlining its cell body. bii, Tracking of this cell across all sessions (24 sessions for this mouse). For each session, the top panel shows the spatial footprint with the cell body outlined in green. The bottom panel shows the across trials averaged calcium response relative to reward onset (mean ± s.e.m.). biii, Calcium responses across sessions show a backward shift. The left panel shows overlapping contours of cell bodies. Each contour is for one session. biv, The same analysis as in biii was repeated, but for each session we replaced registered cells with a nearby randomly selected cells. This shows that the backward shifting disappears. c, Similar to b, for another cell. d, We systematically varied the percentage of misaligned sessions for tracked reward cells. For each misalignment level, we ran 1,000 iterations, randomly selecting a percentage of sessions in each iteration. In these sessions, the registered cell was replaced with a randomly chosen neighbouring cell within a five-cell-diameter radius. As misalignment increased, the negative correlation between reward response and time weakened. e, The results for similar analysis as in d for the entire tracked reward cells. Bar graphs and error bars in d,e show mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Distribution of temporally shifting cells across mice.

a, The top row shows the total number of tracked cells for each cell type; the second row provides the breakdown by mouse (mouse 2 had poor cell tracking and was excluded from this analysis). Each column reports, from left to right, the total number of tracked cells, the subset identified as backward shifting, those identified as forward shifting, and the remaining cells not classified as forward or backward shifting. b, Same layout as in a, but showing the proportion of cells rather than absolute counts. The numbers in the first column are normalized by the total number of tracked cells for each mouse, and subsequent columns are normalized within each cell type (for example, 47 backward-shifting reward cells out of 228 total tracked reward cells). c. Percentage of backward- and forward-shifting cells for each cell type. Reward and reward-approach cells show a higher tendency for backward shifting, whereas screen cells more frequently show forward shifting. Non-classified cells exhibit no strong bias, with roughly equal proportions of forward and backward shifting. d, Correlation of peak activity timing and session number across cell types. e, Temporal shifting score across cell types. For d,e: 228 reward cells, 53 were reward-approach cells, 225 screen cells and 1,308 non-classified cells. Bar graphs and error bars in d,e show mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Distribution of amplitude-changing cells across mice.

a, The first row shows the total number of tracked cells for each functional cell type, while the second row breaks these numbers down by mouse (mouse 2 had poor cell tracking and was excluded from this analysis). Each column reports, from left to right, the total number of tracked cells per cell type, the number of cells identified as declining cells, the number of cells identified as inclining cells, and those identified as forward shifting, and the number of tracked cells not classified as declining or inclining cells. b, Same layout as in a, but showing the proportion of cells rather than absolute counts. The numbers in the first column are normalized by the total number of tracked cells for each mouse, and subsequent columns are normalized within each cell type (for example, 49 declining reward cells out of 228 total tracked reward cells). c. Percentage of declining and increasing cells for each cell type. All three cell types exhibit a higher tendency to decline. Non-classified cells exhibit no strong bias, with roughly equal proportions of declining and inclining. d, Correlation of response amplitude and session number across cell types. e, Amplitude change score across cell types. For d,e: 228 reward cells, 53 were reward-approach cells, 225 screen cells and 1,308 non-classified cells. Bar graphs and error bars in d,e show mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 12 Dynamics of backward-shifting and declining reward cells across sessions.

a, Each point represents the timing of peak activity for a single backward-shifting reward cell in a given session. The black line indicates the session-wise mean peak time, and the error bars denote s.e.m. (scatter plot shows 47 backward-shifting reward cells, each cell tracked across an average of ~10 sessions; total n = 473 data points). b, Similar to a, but showing the response amplitude of declining reward cells instead of timing (scatter plot shows 52 declining reward cells, each tracked across an average of ~12 sessions; total n = 606 data points). Each point corresponds to the peak amplitude of a cell’s activity in a session, with the black line representing the session-wise mean and s.e.m. As expected, a shows a clear backward shift in the timing of peak activity across sessions, whereas b shows a decline in response amplitude. (scatter plot shows 47 backward-shifting reward cells (each tracked across an average of 10 sessions; total n = 623 data points). The black line indicates the within-session average of peak times, and the error bars show the s.e.m. c–f, Comparison of amplitude change scores and temporal shift scores for reward cells (c), reward-approach cells (d), screen cells (e) and non-classified cells (f). The dashed lines show the values of +1.645 or −1.645 which are identical to the 95% and 5% percentiles, respectively. These values set the threshold for cells to be identified as forward, backward shifting or inclining or declining. This analysis across cell types shows a heterogeneous pattern, reflecting a mixture of all possible combinations of temporal and amplitude changes. g, The correlation between peak activity timing relative to reward onset and session number is shown for all cell types. Reward cells and reward-approaching cells exhibit a significant negative correlation, while screen cells and non-classified cells remain stable on average. This negative correlation reflects the backward-shifting property discussed in the paper. h, Same analysis as in g, but here we focused on sessions with delays of 2 s, and we still see similar results. For g,h: 228 reward cells, 53 were reward-approach cells, 225 screen cells, and 1,308 non-classified cells. Bar graphs and error bars in g,h show mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 13 Backward-shifting reward cells.

Each pair of panels shows one backward-shifting reward cell. Top, average activity aligned to reward onset across sessions. Bottom, scatter plot of session number (x axis) versus timing of peak activity (y axis). The correlation value shown at the top quantifies the temporal trend; negative values indicate a backward shift in activity over sessions.

Extended Data Fig. 14 Declining reward cells.

Similar to Extended Data Fig. 13, each pair of panels represents one declining cell. Top, average activity aligned to reward onset across sessions. Bottom, scatter plot of session number (x axis) versus amplitude of peak activity (y axis). The correlation value shown at the top quantifies the change in the response amplitude; negative values indicate a decline in activity over sessions.

Extended Data Fig. 15 Influence of policy on backward shifting of place fields.

a, The task set-up is the same, except that: (1) the agent learns a navigation policy using place-cell activity via an actor with forward/backward actions, and (2) place-field peaks (λ) are modulated by both critic and actor weights11. b, As trials progress, the agent learns to reach the reward faster (reduced latency). Performance increases (orange) or decreases (blue) based on trial-to-trial latency changes. c, Backward-shifting TD error with higher stochasticity across trials. d, Value estimate of each state is updated in a backwards manner across trials. e, At trial 0, basis function peaks are uniformly distributed across states 0 to 9. As learning progresses, backward-shifting TD error causes place-cell peaks to shift backwards, with pronounced backward shifts occurring between states 4 and state 8. Place-field centres organize in the centre of each discrete state to support policy learning. f, Similar to the value learning model (Fig. 5) we observe three shift patterns: (1) reward cells (yellow) shift backwards; (2) approach cells (green) overshoot then shift back; (3) screen cells (purple) shift forwards later. g, 12 examples of individual reward place cells’ activity dynamics between trials 0 to 500. White dash indicates state 7. h, Place cells initialized between states 7 to 8 demonstrate pronounced backward shifts across trials. i, Correlation between peak shift dynamics and session number across cell types. j, Both reward and reward-approach cells show a significantly higher proportion of backward shifting dynamics, whereas screen cells show a significantly higher proportion of forward-shifting dynamics, replicating the proportions in Fig. 4e. k, Reward cells rapidly increase early, then decline. l,m, Quantification of average backward shifting of reward and reward-approach cells across all consecutive days (first column). When consecutive days are grouped based on whether performance increased or decreased, days with reduced performance show greater backward shifting (second column) compared to days with improved performance (third column). l represents modelling results (two-sided t-test p-value = 10^−173) and m represents experimental results (two-sided t-test p-value: 0.0051). l: n (consecutive): 998; n (decreased): 476; n (increased): 458. m: n (consecutive): 121; n (decreased): 53; n (increased): 68. n,o, Hyperparameter sweep for value estimation agent. Because the critic’s weight vector wv was initialized with zeros and the policy was consistently taking the shortest path, there is no stochasticity in the value agent and place-cell dynamics. Hence, the results are for one seed. n, Change (Δ) in percentage of cells is the difference in the number of cells between trial 0 and 1,000 at a specific state. Increasing the total number of available place cells (N) caused a monotonic decrease in the number of cells at the reward state, and increase in approach and screen states, similar to experimental results (γ = 0.95, σ = 0.5). o, As place-cell spread (σ) increased, the number of cells at the reward state decreased while cells at the screen and approach states increased, similar to experimental results. Beyond σ > 0.8, the decrease in reward cell percentage was reduced, although still negative. (γ = 0.95, N = 1,000). Hence, the experimentally observed decrease in the number of cells at the reward state is robust across different numbers of cells and place-field width in our numerical simulations. Bar graphs and error bars in i,l,m show mean ± s.e.m.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file provides a more detailed description of the TD place-cell model.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaghoubi, M., Kumar, M.G., Nieto-Posadas, A. et al. Predictive coding of reward in the hippocampus. Nature (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09958-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09958-0