Abstract

Human genetic variation influences all aspects of our biology, including the oral cavity1,2,3, through which nutrients and microbes enter the body. Yet it is largely unknown which human genetic variants shape a person’s oral microbiome and potentially promote its dysbiosis3,4,5. We characterized the oral microbiomes of 12,519 people by re-analysing whole-genome sequencing reads from previously sequenced saliva-derived DNA. Human genetic variation at 11 loci (10 new) associated with variation in oral microbiome composition. Several of these related to carbohydrate availability; the strongest association (P = 3.0 × 10−188) involved the common FUT2 W154X loss-of-function variant, which associated with the abundances of 58 bacterial species. Human host genetics also seemed to powerfully shape genetic variation in oral bacterial species: these 11 host genetic variants also associated with variation of gene dosages in 68 regions of bacterial genomes. Common, multi-allelic copy number variation of AMY1, which encodes salivary amylase, associated with oral microbiome composition (P = 1.5 × 10−53) and with dentures use in UK Biobank (P = 5.9 × 10−35, n = 418,039) but not with body mass index (P = 0.85), suggesting that salivary amylase abundance impacts health by influencing the oral microbiome. Two other microbiome composition-associated loci, FUT2 and PITX1, also significantly associated with dentures risk, collectively nominating numerous host–microbial interactions that contribute to tooth decay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

When Antonie van Leeuwenhoek first observed bacteria as ‘animalcules’ in scrapings from his teeth in the seventeenth century, one of his first inquiries involved the extent of their variation among people6. Oral microbiomes are now known to vary abundantly across people7,8,9, and twin studies have shown that some of this variation is heritable1,2,3. However, few human genetic polymorphisms have been associated with the abundances of specific oral microbial species3,4,5; study sizes so far (n < 3,000) have provided limited power to detect robust genetic effects. Larger genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of the gut microbiome (n = 5,959–18,340) have consistently replicated two effects of variation at the LCT and ABO loci on gut microbial abundances10,11,12,13, and larger GWAS of oral microbiomes might yield similar discovery.

Oral pathologies, such as dental caries, result from dysbiosis of the oral microbiome14. Untreated pathologies can progress to oral infections which carried high mortality rates before modern dentistry and antibiotics15. Susceptibility to caries and other oral pathologies is also strongly influenced by genetics16,17, and GWAS have identified 47 loci harbouring such genetic effects18. However, whether these or other genetic effects act by modulating the composition of the oral microbiome is at present unknown. Identifying such interactions could point to microbial drivers of cariogenesis9.

Given the effects of human hosts and resident microbes on each other’s survival and evolutionary trajectory, the human microbiome is an example of symbiosis19,20. The stability of the gut microbiome in individuals21, its codiversification with humans22 and abundant structural variation of its microbial genomes23 all suggest intricate genetic interactions between microbiomes and their human hosts, whereby microbial genomes adapt to genetic variation across people. A recently observed example of such an interaction with the gut microbiome is a structural variant in the Faecalibacterium prausnitzii genome that includes genes encoding an N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)-metabolizing pathway and interacts with human ABO variation24. Whether such specific co-adaptation commonly occurs in oral microbiomes remains an open question.

Oral microbiome profiles of 12,519 people

To create a dataset suitable for exploring variation in the oral microbiome and the way it is shaped by human genetic variation, we analysed DNA sequencing reads previously generated from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of saliva samples from 12,519 participants in the Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research (SPARK) cohort25 (Fig. 1a), building on previous work26,27. WGS captured substantial non-human genomic information28, with a median of 8.4% ([4.6%,14.7%], quartiles) of sequencing reads not mapping to the human reference genome (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Many of these unmapped reads instead mapped to clade-specific marker genes in microbial genomes29, enabling quantification of relative microbial abundances. This produced the largest collection of oral microbiome profiles (n = 12,519) generated so far, measuring the abundances of 645 microbial species present at >1% frequency, including 439 species (spanning 13 phyla, including one fungal commensal, Malassezia restricta) commonly observed in SPARK (≥10% of participants) (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). Comparing these profiles across individuals showed that age was a major driver of interindividual variation in oral microbiome composition, unlike autism spectrum disorder (ASD) case status, sex and genetic ancestry (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1c–g). Across the lifespan represented in SPARK (age 0–90 years), mean species diversity sharply increased in the first few years of life (representing when the oral cavity is colonized, diet diversifies and primary teeth are acquired) and then decreased slowly with age8 (Fig. 1d). Individual species exhibited vastly different abundance trajectories over the lifespan, with some observed predominantly in adults and others predominantly in children (Extended Data Fig. 1h–k).

a, Generation of paired datasets of human genetic variation and oral microbiome composition from WGS of saliva samples from the SPARK cohort (n = 12,519). Human genetic variants were previously called with DeepVariant and relative abundances of microbial species were estimated with MetaPhlAn 4 (ref. 29) from sequencing reads that did not map to the human genome. b, Phylogenetic tree based on genomic divergence among 439 microbial species observed in ≥10% of SPARK participants. Phyla are indicated by dot colour and genera with more than five species are indicated with labelled grey sectors. c, Contributions of age, sex, ASD case status and genetic ancestry principal components (PC1 through PC5) to variation in oral microbial species abundances. For each factor, the fraction of variance in species abundance explained by the factor was computed for each of the 439 species, and the box and whisker plot shows the distribution of this quantity across the 439 species. ASD status explained a median fraction of variance of 0.002. Boxes span quartiles; centres indicate medians and whiskers are drawn up to 1.5× the interquartile range. d, Species diversity in the oral microbiome as a function of host age. The red line indicates median Shannon entropy and the shaded region indicates the interquartile range. Oral microbial diversity increases substantially over the first few years of life, plateaus and then modestly declines in late adulthood. Images in a were reproduced from Pixabay (https://pixabay.com) under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Licence.

Human genetics shapes oral microbiome composition

To identify human genetic variants that influence interindividual differences in the abundances of microbial taxa, we first tested the abundances of taxa detectable in ≥10% of participants for association with common human genetic variants, accounting for family structure using a linear mixed model30,31. Human genetic variants at seven loci associated with the abundance of at least one taxon at study-wide significance (P < 4.0 × 10−11; Extended Data Fig. 2a), with only one locus (SLC2A9) previously identified4. As several loci associated with the abundances of many species (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3) and none associated with α-diversity (Extended Data Fig. 2b), we developed a statistical test to capture pleiotropic effects on many species in an interdependent microbial community32,33,34, using principal component analysis (PCA) to enable efficient genome-wide association testing (Fig. 2a and Methods). Similar to a recent approach for GWAS on high-dimensional cell state phenotypes in single-cell RNA-seq data35, this approach also reduces multiple-testing burden by testing each genetic variant only once.

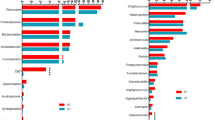

a, Converting relative abundances of M microbial species (left) into M orthogonal PCs (middle) allows combining chi-squared statistics for a given genetic variant (one per PC) into a single chi-squared test statistic with M degrees of freedom (right). b, Genome-wide associations with oral microbiome composition in SPARK (top, n = 12,519) and dentures use in UKB (bottom, n = 418,039). Nonsense (red squares), missense (green triangles) and multi-allelic copy number variants (CNVs) (blue diamonds) are highlighted. c, Associations of variants at the FUT2 locus with relative species abundance for the five microbial species with the strongest associations (left five plots); colour indicates effect direction (plots with red points correspond to species which are more abundant in people with functional FUT2 (that is, secretors); blue, less abundant) and colour saturation indicates linkage disequilibrium with rs601338 (FUT2 W154X). Association strengths from the combined test for association with oral microbiome composition show much greater statistical power (rightmost plot). d, Effect sizes (in s.d. units) on relative abundance of microbial species for individuals heterozygous for functional FUT2 (light-filled circles) and for homozygotes (dark-filled circles) relative to those with no functional FUT2 (empty circles). For each effect direction, the ten most significantly associated species are shown. P values are from a recessive model of FUT2 W154X genotype. Error bars, 95% CIs. e, Microbial taxa whose abundance associated with FUT2 genotype (FDR < 0.1) shown on the phylogenetic tree of 439 species (red, taxa whose relative abundances increased with functional FUT2; blue, decreased). Two significantly associated phyla (Firmicutes and Actinobacteria; P = 1.2 × 10−4 and 4.0 × 10−5, respectively) are highlighted with yellow sectors. At the species level (outermost circle), dot sizes increase with statistical significance. P values were computed using one-sided chi-squared test (top half, b), two-sided linear regression (bottom half, b) or two-sided linear mixed models (c,d).

Applying this approach to SPARK identified four additional human genomic loci (11 total) at which common genetic variation associated with oral microbiome composition (P < 5 × 10−8; Fig. 2b and Extended Data Table 1). The principal component (PC)-based test was well-calibrated (Extended Data Fig. 2c) and top signals were confirmed by multivariate distance matrix regression33,36 (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). The association signals tended to distribute across many microbial PCs (mPCs; Extended Data Fig. 2f–p), suggesting that human genetic variants subtly influence many axes of microbial community coordination. Among the ten new loci, eight implicated genes—and in several cases, specific variants—with readily interpretable functions that could explain their associations with microbiome composition.

-

Three loci contained genes encoding highly expressed salivary proteins: salivary amylase (encoded by AMY1; P = 1.5 × 10−53, top association), submaxillary gland androgen-regulated proteins (SMR3A and SMR3B; P = 1.4 × 10−12) and basic salivary proline-rich proteins (PRB1–PRB4; P = 1.1 × 10−11). These associations seemed to be driven mainly by genetic variants that modify gene expression or copy number (Extended Data Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 1). Consistent with these results, heritability-partitioning analysis37 indicated that genetic effects on oral microbiome composition are enriched at genes specifically expressed in salivary glands (P = 0.02, Extended Data Fig. 4a).

-

Two loci contained genes with established roles in immune function: the HLA class II genes, which encode proteins that present peptides in adaptive immunity, and TLR1, encoding Toll-like receptor 1, that binds bacterial lipoproteins in innate immunity. The strongest association at TLR1 involved a missense variant (rs5743618; P = 6.2 × 10−18) that produces the I602S substitution known to inhibit trafficking of TLR1 to the cell surface, reducing immune response in a recessive manner38,39. Consistent with these reports, I602S associated recessively with microbial abundances (P = 6.7 × 10−29; Extended Data Fig. 4b).

-

Two other loci, ABO and FUT2, encode glycosyltransferases that together determine expression of histo-blood group antigens on epithelial cells and secreted proteins (in addition to the well-known role of ABO in determining blood type). This broader role is important to microbial species that interact with mucosal surfaces, such that both loci are known to influence the gut microbiome10,11,12,13, with some bacterial species using A-antigen saccharides as a carbohydrate source24. The variants at ABO and FUT2 that associated most strongly with oral microbiome composition were rs2519093 (P = 9.5 × 10−15), which tags the A1 blood group40, and rs601338 (P = 1.6 × 10−131 additively, P = 3.0 × 10−188 recessively), the common FUT2 W154X nonsense variant that (in homozygotes) produces the non-secretor phenotype in which bodily fluids lack histo-blood group antigens41.

-

Associations of variants at PITX1 with oral microbiome composition colocalized with previously reported associations of these variants with dental caries and dentures use (r2 = 0.99 between the top microbiome-associated variant (rs3749751; P = 3.0 × 10−11) and the top dentures-associated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at PITX1; Extended Data Fig. 4c; ref. 18). PITX1 is a developmentally expressed gene which seems to have a role in mandibular tooth morphogenesis (based on a knockout mouse model)42, suggesting that common genetic variation at PITX1 might influence tooth morphology and through it, oral microbiota and dental health.

The shared associations of genetic variants at PITX1 with both oral microbiome composition and dental health phenotypes suggested that other genetic influences on the oral microbiome might similarly influence dental health. To explore this, we performed GWAS of dentures use (a proxy for tooth loss and caries) in the UK Biobank (UKB) cohort (n = 75,156 cases, n = 342,883 controls)43. Three loci—AMY1, FUT2 and PITX1—contained variants that associated (P < 5 × 10−8) with both oral microbiome composition and dentures use, and at each of these loci, the association patterns colocalized (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). Moreover, at 8 of the 11 loci influencing oral microbiome composition, the most strongly associated variant also exhibited at least a nominal association (P < 0.05) with dentures risk (Extended Data Table 1), suggesting that host genetic effects on oral microbiome composition often have downstream effects on oral health.

Most of these genetic associations seemed to involve effects of human genetic variation on the abundances of several bacterial species, with 167 species–genotype pairs reaching FDR < 0.05 across the 11 loci (Supplementary Table 3). These associations were not driven by compositional effects or by ASD status (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f). The strong associations at AMY1 and FUT2 offered an opportunity for detailed investigation of how genetic variation at these loci influences oral microbiomes and oral health. FUT2 W154X associated with the abundances of 58 of the 439 species (Fig. 2c–e). FUT2 seemed to be nearly but not completely haplosufficient in these associations, with slightly weaker abundance-modifying effects observed among secretor individuals with a heterozygous W154X genotype compared to those with two wild-type alleles (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 4g). For several pairs of closely related species, FUT2 W154X associated with increased abundance of one species and decreased abundance of the other (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5), possibly reflecting competition between closely related species for ecological niches.

Effects of complex variation at the amylase locus

AMY1 encodes salivary α-amylase, an enzyme that breaks down dietary starches into simple sugars. The dramatic copy number expansion of the amylase locus in humans and other animals44 has attracted much interest for its theorized role in facilitating recent adaptation to starch-based diets45,46,47, but its reported association with human body mass index (BMI)48 and type 2 diabetes49 has been controversial50,51. AMY1 copy number genotypes in SPARK and UKB (estimated from WGS depth-of-coverage) showed extensive polymorphism45,50 (2–32 copies per individual; Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6a) and high mutability (6.3 × 10−4 (3.7 × 10−4–11 × 10−4, 95% confidence interval (CI)) mutations per haplotype per generation, similar to an estimate using coalescent modelling46; Extended Data Fig. 6b).

a, Distribution of AMY1 diploid copy number estimates for UKB participants (n = 490,415). Inset, diagram of the amylase locus in the human reference genome with common variable cassettes46,47. b, Effect sizes on relative species abundance for the 16 species most strongly associated with host AMY1 copy number (FDR < 0.01). c, Allelic series of effect sizes of AMY1 copy number genotypes on normalized abundances of Prevotella pallens and TM7 phylum sp. oral taxon 351 (n = 12,487). d, Odds ratios for risk of dentures use in UKB (n = 418,039) across copy number genotypes of AMY1 (purple), AMY1 F141C (red) and AMY1 C477R (blue). e, Odds ratios for risk of bleeding gums in UKB (n = 418,039). f, Associations of variants at the amylase locus with dentures use. Plotted variants include paralogous sequence variants (PSVs) in the AMY1 region (for which copy numbers of minor alleles were tested for association). Dot colours indicate linkage disequilibrium (LD) with AMY1 copy number. g, Associations with dentures use conditioned on AMY1 copy number. h, Associations with dentures use additionally conditioned on AMY1 F141C copy number. i, Comparison of effect sizes for AMY1 copy number versus AMY1 F141C copy number on relative abundances of 16 microbial species (from b, n = 12,519) and on risk of dentures use (large black dot, n = 418,039). For some species, the relative effect size of AMY1 copy number versus AMY1 F141C copy number on abundance differs significantly from this ratio for dentures use (black line). j, Effect sizes of AMY1 copy number genotypes on BMI in UKB (n = 418,150). The line drawn is the best fit across AMY1 copy numbers. Error bars, 95% CIs in all panels. P values were computed using two-sided linear mixed models (b) and linear regression (f–h,j).

Copy number variation of AMY1 generated the strongest association of genetic variation at the amylase locus with oral microbiome composition (P = 1.5 × 10−53; Fig. 2b) and associated with the abundances of 42 bacterial species (FDR < 0.05, 22 species at FDR < 0.01 with P = 5.1 × 10−25 to P = 0.00047; Fig. 3b). The abundances of these species changed stepwise with AMY1 copy number, generating a long allelic series with steadily increasing or decreasing abundances (Fig. 3c), congruent with the effect of AMY1 copy number on the abundance of secreted salivary amylase45,52. Two of these associations seemed to confirm associations previously observed in smaller candidate gene studies49,53 (Supplementary Note 2).

AMY1 copy number also associated strongly with dentures use in UKB (P = 5.9 × 10−35, surpassed only by the PITX1 locus; Fig. 2b). Each additional copy of AMY1 associated with a 2.1% (1.7%–2.4%) increase in the odds of having dentures, corresponding to a 1.4-fold range in odds across people with 2–16 AMY1 copies (Fig. 3d). This association replicated in the All of Us (AoU) cohort54 (n = 230,002; P = 3.5 × 10−4 for tooth loss, P = 6.1 × 10−3 for caries; Extended Data Fig. 6c–e). Surprisingly, AMY1 copy number associated with decreased risk of bleeding gums in UKB (P = 1.5 × 10−6; Fig. 3e), even though gingivitis is considered a risk factor for tooth loss55,56. However, the bleeding gums and dentures use phenotypes had little genetic overlap18 and were slightly negatively correlated (r = −0.07, s.e. 0.0015), suggesting largely independent pathology. These associations were specific to AMY1; the copy number of AMY2A and AMY2B (encoding pancreatic amylase) did not associate with dental phenotypes (Extended Data Fig. 6f,g).

Beyond the effect of AMY1 copy number, two missense variants in AMY1 carried by 1%–2% of UKB participants seemed to confer the largest increases in dentures risk of all common variants in the human genome (OR = 1.59 (1.46–1.73) per copy of AMY1 F141C (P = 2.5 × 10−26); OR = 1.16 (1.10–1.23) per copy of AMY1 C477R (P = 8.3 × 10−8); Fig. 3d). These two paralogous sequence variants were typically carried on haplotypes containing three or four copies of AMY1 and produced the strongest conditional associations with dentures use in two stages of stepwise conditional analysis (Fig. 3f–h). The AMY1 F141C and C477R variants seemed to confer an increase in dentures risk equivalent to increasing AMY1 copy number by 22.4 (18.3–26.5) and 7.3 (4.6–9.9) copies, respectively (Fig. 3d). This apparent gain-of-function effect was surprising, as both variants were predicted to be damaging (PolyPhen-257 score of 1.0). Analyses of amylase protein expression did not detect effects of AMY1 F141C on enzymatic activity (Supplementary Note 3, Extended Data Fig. 7a–c and Supplementary Fig. 1). The extended allelic series of AMY1 copy number and missense variants associated with dentures use provided a set of genetic instruments for evaluating which bacterial species might causally contribute to tooth loss (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 7d). Reverse causality (that is, dentures use causing changes in the oral microbiome that associate with AMY1 variants) seemed to be unlikely based on the concordance of effect sizes in children and adults (Extended Data Fig. 7e).

The UKB and AoU datasets also enabled rigorous evaluation of whether or not AMY1 copy number influences BMI among modern humans. AMY1 copy number did not associate with BMI in UKB (n = 418,150, P = 0.85; Fig. 3j), AoU (n = 219,879, P = 0.30, Extended Data Fig. 7f) or any genetic ancestry in AoU (Extended Data Fig. 7g–i).

Genetic associations with bacterial gene dosage

To identify molecular mechanisms by which human genetic variation engages the oral microbiome, we next tested whether the microbial species for which abundances associated with each of the 11 loci might be united by shared biochemical pathway use58 (Extended Data Fig. 8a, Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 and Supplementary Note 4). This analysis identified an adhesin gene in Haemophilus sputorum at which sequencing coverage associated particularly strongly (relative to elsewhere in the H. sputorum genome) with FUT2 W154X, suggesting that the adhesin interacts with FUT2-dependent glycosylation (Extended Data Fig. 8b and Supplementary Note 4). To search for similar molecular interactions between human and bacterial proteins, we tested the 11 lead variants associated with oral microbiome composition (Extended Data Table 1) for association with microbial gene dosages24 (Fig. 4a). The key conceptual difference between testing human genetic variants for effects on microbial abundances (Fig. 2a) versus microbial gene dosages (Fig. 4a) is that the latter approach searches for effects on relative fitness of bacterial strains that do or do not contain a genomic region (rather than fitness of a bacterial species). Thus, it highlights microbial genomic regions that may contain genes whose products are involved in a host–microbe genetic interaction (Supplementary Note 5).

a, Approach to identify deletions in microbial reference genomes that associate with 11 human genetic variants that influence oral microbiome composition (Extended Data Table 1). Sequencing reads were remapped to 30 microbial reference genomes, after which normalized WGS coverage was computed across 500 bp genomic bins and truncated to a maximum of 1. b, Associations between microbial gene dosage (based on normalized WGS coverage) and human genetic variants. Each dot indicates a microbial genomic region that associated with at least one human genetic variant (circles, Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05; triangles, FDR < 0.01). Dot colours indicate human loci and regions that associated with more than one human locus are marked with an asterisk (top). P values were computed using two-sided linear regression (b).

To minimize hypothesis testing burden, we searched specifically for associations of the 11 variants with measurements of normalized WGS coverage in 500 base pair (bp) bins tiled across 30 bacterial reference genomes (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 6, Methods and Supplementary Note 5). This analysis identified 208 associations involving 68 regions of 18 bacterial genomes in which normalized read depth associated with one or more of the 11 human genetic variants (FDR < 0.01, Fig. 4b and Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). For example, amylase-binding protein orthologues in Streptococcus parasanguinis, abpA and abpB, increased in dosage with higher host AMY1 copy number (P = 1.13 × 10−7 and 1.80 × 10−7, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 8c–g and Supplementary Note 6). Normalized read depth in nearly half of these regions (33/68) associated with secretor status (based on FUT2 W154X genotype). Eight regions associated with more than one human genetic variant; among them, five regions associated with both secretor status and ABO*A1 (Fig. 4b). Effect directions replicated for 202 of the 208 bin-level associations in 10,000 saliva-derived WGS samples from AoU (Extended Data Fig. 8h and Supplementary Table 7).

ABO A antigen selects for a glycoside hydrolase

Host ABO*A1 genotype (based on rs2519093) strongly associated with whether Prevotella strains—a prevalent oral genus involved in early biofilm formation59—carried a gene encoding a glycoside hydrolase (Fig. 5a–d). ABO*A1 genotype associated exceptionally strongly (P = 4.8 × 10−19–8.3 × 10−241) with normalized WGS coverage across a 3 kilobase (kb) segment of the Prevotella nanceiensis reference genome (Fig. 5a). This region is annotated as a glycoside hydrolase pseudogene due to an N-terminal truncation in the reference genome. However, assembly of unmapped sequencing reads with mates aligned to the region showed no evidence of such truncation: rather, the reads seemed to originate from a full-length gene, with 95% homology to a glycoside hydrolase found in Prevotella salivae (a species not included among the 30 reference genomes analysed).

a, Associations of host ABO*A1 genotype with normalized coverage (truncated at 1) in 500 bp bins of the P. nanceiensis genome surrounding a glycoside hydrolase gene (n = 10,433). Dot colour, effect direction (red, higher coverage among individuals with A1 blood type); dot size, effect magnitude. Arrows indicate genes: glycoside hydrolase pgh95 (A3GM_RS0109435, green), other genes overlapping the region associated with ABO*A1 (black) and nearby genes (grey). P values, two-sided linear regression. b, Proportion of individuals whose oral microbiomes carry the pgh95 gene (n = 10,433), stratified by blood type and secretor status. c, Effect sizes on normalized coverage in the pgh95 region (123,500–124,000) for genotype combinations of common blood type alleles (O, B, A2 and A1) relative to O/O individuals. Analyses were restricted to secretors (n = 8,278). Effect sizes seem to reflect expected abundances of A antigens (yellow squares, A antigens; grey circles, B antigens). d, Inferred interaction between glycosylation of host cell proteins and bacterial glycoside hydrolase. Top (pink background), glycosylation patterns of human mucosal cell surface proteins and secreted proteins depend on an individual’s combination of FUT2 and ABO genotypes. In individuals with no functional copies of FUT2 (non-secretors), type I H antigen is not produced, whereas in secretors, type I H antigen is produced and can be further glycosylated into A antigen or B antigen depending on ABO genotype (dashed purple outline). These antigens are then presented on mucosal cell surface and secreted proteins. The associations of ABO genotypes with presence of the pgh95 gene in Prevotella strains suggest that the bacterial glycoside hydrolase protein (PGH95, green) is specifically targeting secreted type A antigens and cleaving the α1,2-fucosyl group, consistent with high amino acid homology (~75%) with α1,2-fucosidases in the glycoside hydrolase 95 (GH95) family. e,f, Analogous to b,c, respectively, for the ABO-associated region in R. mucilaginosa (n = 12,475). Error bars, 95% CIs in all panels.

ABO*A1 genotype associated with sequencing coverage in this region only in secretor individuals (P = 1.7 × 10−307 in secretors; P = 0.44 in non-secretors), that is, individuals with at least one functional copy of FUT2, allowing expression of histo-blood group antigens on epithelial cells and secreted proteins (Fig. 5d). This FUT2-dependent effect of host blood group seemed to be driven specifically by A antigen presentation: the fraction of individuals for whom the glycoside hydrolase gene was detectable in saliva-derived DNA increased from 46%–48% in non-secretors and individuals with B or O blood type to 71%–77% in secretors with A or AB blood type (Fig. 5b). This association further reflected the quantity of A antigen predicted by an individual’s diploid ABO genotype: ABO*O, B, A2 and A1 alleles exhibited an allelic series of effects on normalized WGS coverage of the glycoside hydrolase gene that was consistent with the increasing abilities of the glycosyltransferases encoded by these alleles to synthesize A antigen (Fig. 5c). The B allele imposed a strong opposing effect when present in an individual heterozygous for an A1 or A2 allele (β = −0.074 [−0.12, −0.032] for B relative to O, P = 5.8 × 10−4, Fig. 5c), presumably reflecting competition between A and B transferases for available galactose residues on acceptor H antigens (Fig. 5d).

Taken together, these results indicate that the glycoside hydrolase enables Prevotella strains that express it to use type A histo-blood group antigens presented on host mucosal cell surfaces or salivary proteins (in secretors) as a carbohydrate source, similar to a recently observed effect in the gut microbiome24. We hypothesize that the glycoside hydrolase binds A antigens and cleaves the α1,2-fucosyl group synthesized by FUT2 (Fig. 5d).

Host ABO genotypes showed an intriguingly different pattern of association with a genomic region of the most abundant species in SPARK, Rothia mucilaginosa (P = 1.4 × 10−24; Fig. 5e,f). Blood groups A, B and AB all associated with absence (rather than presence) of this region of the R. mucilaginosa genome, and surprisingly, these associations were observed in non-secretors as well as secretors (Fig. 5e,f). This region contains genes that encode a protein with no annotated domains and a 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase functioning in leucine biosynthesis, leaving the mechanism of association unknown.

More broadly, this non-FUT2-dependent ABO association suggested the possibility that the association of ABO*A1 genotype with oral microbiome composition (Fig. 2b) might also be partially independent from secretor status. Indeed, in non-secretors the ABO*A1 association with microbiome composition remained significant (P = 0.004). This suggests that some effects of ABO variation on the oral microbiome come from cells not dependent on FUT2 for H antigen production (for example, blood and endothelial cells, which instead use FUT1). For example, bacteria can produce glycans structurally similar to A or B antigens that can then be recognized by anti-A or anti-B antibodies that are made by plasma cells and infiltrate into the mouth60.

Secretor status selects for microbial adhesins

Conversely, many regions in oral microbial genomes associated with secretor status but not ABO*A1 genotype (Fig. 4b), and oral microbiome composition associated much more strongly with secretor status than with any variant at ABO (P = 3.0 × 10−188 versus P = 9.4 × 10−15; Fig. 2b). This pattern contrasted with host genetic influences on gut microbiomes (which generate stronger associations at ABO than at FUT2; refs. 11,12,13), leading us to wonder whether these regions might point to a molecular mechanism by which secretor status influences oral microbiomes independently of ABO.

Examining genes in bacterial genomic regions associated with secretor status identified three classes of bacterial proteins that were each implicated by several genes. Proteins with YadA-like domains were encoded by nine genes in three species: Veillonella sp. 3627 (vadA through vadF), Haemophilus sputorum (hadA and hadB) and Haemophilus parahaemolyticus (hadC) (Fig. 6a–d and Supplementary Table 8). YadA (from Yersinia pestis) is a trimeric autotransporter adhesin that aids attachment to host cells by binding components of the extracellular matrix, and some such adhesins are known to recognize host protein glycosylation61,62, such as the glycosylation added or enabled by FUT2. Five of the seven regions containing these genes were present (that is, not deleted) more often in the oral microbiomes of secretors than non-secretors, consistent with the hypothesis that the adhesins they encode bind histo-blood group antigens on the host cell surface. This was true of hadC in H. parahaemolyticus despite this species exhibiting lower abundance in secretors (Extended Data Fig. 8i). The genome of V. sp. 3627 contained three such regions (containing vadB through vadF, where vadC through vadE fall within the same complex region, Extended Data Fig. 8j) whose presence or absence was observed largely independently in different microbiomes (Fig. 6e). Classifying individuals on the basis of which combination of regions was present in their V. sp. 3627 population showed increasing enrichment of secretors among individuals with increasing representation of vadB–vadF genes in V. sp. 3627 (Fig. 6e).

a, Associations of secretor status with normalized coverage (truncated at 1) in 500 bp bins of the V. sp. 3627 genome (n = 7,419). Shading indicates assembled contigs. Significant associations (FDR < 0.01) that overlap genes encoding proteins with YadA-like domains are highlighted (blue, genomic region more often present in secretors; red, absent). Effect directions are also indicated for bins that did not reach significance but were surrounded by significantly associated bins. b, Analogous to a, for H. sputorum (n = 8153). c, Analogous to a, for H. parahaemolyticus (n = 7,456). d, Predicted trimeric structure of VadD (from V. sp. 3627), where the head domain (blue) facilitates attachment to host proteins, stalk domains (magenta) flexibility and reach, and anchor domain (gold) translocation to bacterial surface. e, Upset plot of the relative proportions of FUT2 W154X genotypes (non-secretors in grey, secretors in orange) among individuals with each combination of vadB–vadF gene deletions in the V. sp. 3627 genome. Analysis was restricted to individuals with each gene either primarily present in strains of V. sp. 3627 (normalized coverage >0.8) or primarily absent (normalized coverage <0.2). Blue-to-grey shading of sets (bottom) and numbers of individuals per set (top) indicate the number of vad genes present. f, Analogous to a, for S. mitis (n = 12,479). Highlighted genes encode proteins that contain either a CshA domain (crp genes) or mucin-binding domain (smd genes). g, Analogous to f, for S. vestibularis (n = 11,723). h, Predicted structure of a portion of CrpE from S. mitis. The CshA NR2 (gold) and mucin-binding domains (magenta) both have lectin activity to their characterized ligands (fibronectin and mucin)63,64. i, Model of how host FUT2 genotype selects for bacterial strains expressing proteins with YadA, CshA or mucin-binding domains that can attach to host cell surface proteins based on the availability of histo-blood type antigens. P values, two-sided linear regression (a–c,f,g).

FUT2-associated genomic regions additionally implicated two other classes of proteins that seemed to have roles in adhesion to host cells. Four proteins with CshA domains (CrpD and CrpE in Streptococcus mitis, CrpF and CrpG in Streptococcus vestibularis) and six proteins with mucin-binding domains (MucBP, Muc_B2, MucBP_2) (SmdA through SmdE in S. mitis, SmdF in S. vestibularis) were encoded by genes in FUT2-associated bacterial genomic regions (Fig. 6f,g). CshA from Streptococcus gordonii binds host fibronectin63, a heavily glycosylated component of the extracellular matrix. Similarly, mucins have numerous glycosylation sites and are up to 90% carbohydrate by mass64. Interestingly, one of these proteins, CrpE in S. mitis, seems to contain both a CshA domain and multiple mucin-binding domains (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Table 9), suggesting that these might function in concert to bind the same host protein or a combination of proximal targets multivalently.

These enrichments of genes encoding proteins with YadA, CshA and mucin-binding domains were unlikely to occur by chance: the genomes of V. sp. 3627, H. sputorum and H. parahaemolyticus only contain 12, 4 and 8 genes with YadA domains, respectively (Fisher’s exact P = 7.5 × 10−12, 3.5 × 10−5 and 0.021), and the genomes of S. mitis and S. vestibularis only contain two and three genes with CshA domains (P = 7.4 × 10−5 and 2.0 × 10−5) and ten and three genes with mucin-binding domains (P = 3.3 × 10−11 and 0.0087). Most of these genes (15/19) were more commonly present in the oral microbiomes of people with functional FUT2, suggesting that they might encode bacterial lectins that depend on either fucosylation or sugar moieties added by ABO glycotransferase65 (Fig. 6i). This convergence of bacterial genomic adaptations to host FUT2 genotype broadly suggests that commensal bacteria commonly make use of host histo-blood group antigens not only as a carbohydrate source but also for bacterial attachment to host cell surfaces.

Discussion

Analysis of the largest set of oral microbiome profiles generated to date identified many specific human genetic variants that contribute to the diversity observed across the oral microbiomes of different people7,8. The large number of such effects suggests a larger influence of human genetics on the oral microbiome than on the gut microbiome66,67, perhaps because host cells in the mouth interface more directly with bacteria (in contrast to cells in the gut, which are typically protected by a mucosal barrier). Some of these genetic effects on microbial abundances seem likely to mediate associations of the same human genetic variants with oral health phenotypes, nominating bacterial species that may contribute to dysbiosis. The salivary amylase gene generated the strongest such shared effect on oral microbiomes and health, driven by both AMY1 copy number variation and missense mutations in AMY1. The expansion of salivary amylase copy number in humans and domesticated animals has been hypothesized to be the result of positive selection driven by the advent of agriculture44,45,46,47. Our observation here that AMY1 gene copy number variation associates with oral microbial phenotypes that lead to clinically relevant conditions—combined with the high mortality rate of tooth infections before modern dentistry and antibiotics15—suggests that AMY1 copy number may have been under selection as a result of effects on oral health in addition—or in response—to dietary changes.

The numerous associations that these analyses uncovered between human genetic variants and bacterial gene dosages suggest frequent intergenomic adaptation of microbial species to individual human hosts and implicate specific molecular interactions likely to drive such adaptation. Most of these associations involved genes in bacterial species whose overall abundances were unaffected by the same human genetic variants, similar to recent observations of associations of BMI with gut microbial sequence variation68, suggesting that genomic adaptations enable many bacterial species to survive equally well across variable host genetic environments. By contrast, an association with relative species abundance could imply that the microbial genome is unable to adapt to a particular human variation. The variable gene regions we identified showed some breakpoint heterogeneity (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b) and could either reflect gene dosage variation among circulating strains or recurrent mutations, such as in Helicobacter pylori69. The large number of such effects suggests that analyses of bacterial gene dosage may be a powerful way to identify host genetic influences on microbiomes, perhaps because analysing the balance between members of the same species with and without a variable gene controls for strong environmental influences on species abundance.

We note a need for care in conducting GWAS of microbial-abundance phenotypes. We initially observed a strong association (P = 2.5 × 10−70) of oral microbiome composition with variant calls in the ribosomal RNA gene region of the p-arm of chromosome 21; however, these variant calls (which later failed a mappability filter) actually reflected the presence of orthologous bovine rDNA sequences and associated with the abundances of bacterial species used in dairy fermentation, suggesting DNA co-acquisition from recently eaten dairy foods (Supplementary Note 7). Our analytical approach for identifying host–microbe genetic interactions had several limitations that should be ameliorated with larger cohorts and improved microbial reference genomes (Extended Data Fig. 9c–h and Supplementary Note 8). Future datasets will also provide increased power to resolve possible pleiotropy and reverse causality with oral health phenotypes, either through cohorts with human genetic, microbiome and oral health phenotypes70 or by Mendelian randomization approaches powered by even larger saliva sequencing datasets—which we have shown here provide rich information about how oral microbiomes are shaped by human genetics.

Methods

Ethics

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The study protocol was determined to be not human subjects research by the Broad Institute Office of Research Subject Protection as all data analysed were previously collected and de-identified.

Quantification of microbial relative abundances from saliva WGS

We analysed saliva-derived WGS data previously generated for 12,519 individuals from the SPARK cohort of the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI)25. In brief, DNA extracted from saliva samples was prepared with PCR-free methods for 150 bp paired-end sequencing on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 machines. Reads were aligned to human reference build GRCh38 by the New York Genome Center using Centers for Common Disease Genomics project standards. Details of saliva sample collection, DNA extraction and sequencing were described in ref. 26 (which analysed data from sequencing waves WGS1–3 of the SPARK integrated WGS (iWGS) v.1.1 dataset; here we analysed WGS1–5, which included additional samples included in subsequent sequencing waves).

From the CRAM files previously aligned to GRCh38, we extracted all unmapped reads for subsequent generation and analysis of oral microbiome phenotypes. This retrieved a median of 67.5 million unmapped reads per sample ([35.9 million,126.1 million], quartiles), comparable with the total number of reads used for previous metagenomic characterization of human microbiomes71 and consistent with previous analyses of SPARK samples for oral microbiome profiling26,27. Unmapped reads were converted to compressed FASTQ with samtools (v.1.15.1) and then used as input for microbiome profiling using MetaPhlAn (v.4.0.6) with the vOct22 reference database. To evaluate robustness of these oral microbiome profiles, relative abundances of species in SPARK samples were compared with those from samples in the Human Microbiome Project72 by first subsetting to those profiled in both cohorts and then performing principal coordinate analysis using Bray–Curtis distance (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

From the relative abundance phenotype generated for each species by MetaPhlAn, we estimated the fractions of variance explained by covariates (age, sex, ASD and genetic ancestry PCs; Fig. 1c) using analysis of variance (finding the sum-of-squares for each covariate and dividing by the total sum-of-squares).

Generation of mPCs

Relative abundance measures of all microbes were first filtered to 439 entries corresponding to microbial species found in at least 10% of SPARK DNA samples. Rank-based inverse normal transformation across individuals was then performed for the abundance of each species. This transformation did not always produce values with mean 0 and variance 1 (due to large fractions of samples with zero abundance), so these were then scaled and centred for use as input to PC analysis to obtain 439 orthogonal microbial abundance principal components (mPCs) representing orthogonal axes of microbial variation.

Genotyping and quality control of human genetic variants in SPARK

Variant calling in SPARK was previously performed using DeepVariant (v.1.3.0) to produce sample-level VCFs from reads aligned to GRCh38 followed by GLnexus (v.1.4.1) to call variants jointly across the cohort. We performed a series of QC steps on the joint call set, starting by converting half-calls to missing and then excluding variants with >10% missingness using plink2 (v.2.00a3.6LM). Variants were further excluded if they had a minor allele frequency <1% or if they had a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium exact test P < 1 × 10−6 with mid-P adjustment for excessive heterozygosity, leaving 12,525,098 common variants. Genetic ancestry PCs were generated by LD-pruning variants in 500 kb windows with r2 > 0.1 and then running plink2 --pca approx. No individuals were filtered for outlier heterozygosity after inspection in each genetic ancestry group. Variants were then filtered to those present in the TOPMed-r3 imputation panel to exclude those in regions of poor mappability to produce a final set of 9,618,621 common variants to test for association with oral microbiome phenotypes.

mPC-based GWAS of oral microbiome composition

A straightforward way to search for host genetic effects on microbiomes is to test human genetic variants for association with the abundance of each microbial taxon in turn10,11,12,13. However, we reasoned that a statistical test designed to aggregate evidence of pleiotropic genetic effects on many species in a microbial community could considerably increase statistical power32,33,34. To perform such a test in a scalable manner (efficient enough to test millions of human genetic variants), we made use of the decomposition of the microbial abundance matrix into 439 orthogonal mPCs. Specifically, we tested each genetic variant for association with each rank-based inverse normal transformed mPC, after which we summed the 439 test statistics obtained per variant to compute a single, combined association test for each variant (Fig. 2a; details in next section). Beyond increasing power to detect pleiotropic effects, the approach reduces multiple-testing burden by testing each genetic variant only once. We evaluated applying this approach to a subset of top axes of microbial variation (rather than all 439 mPCs) but did not observe a further increase in power, consistent with many axes of variation contributing association signal in this dataset (Extended Data Fig. 2f–p).

Details of GWAS of oral microbiome composition

We performed GWAS on each mPC phenotype using the linear mixed model implemented in BOLT-LMM to account for the family structure of the SPARK cohort30,31,73. Specifically, we ran BOLT-LMM using the --lmmInfOnly flag (as the non-infinitesimal mixed model provided a negligible increase in statistical power) with the following covariates: sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex, percentage of mapped reads and the top ten genetic ancestry PCs. A single father without a recorded age was assigned the average age of other fathers in the dataset. AMY1 and PRB1 copy numbers were rescaled to a range of [0,2] and encoded as dosages for association testing.

To test a genetic variant for association with an effect on overall oral microbiome composition, we summed chi-square statistics across the 439 orthogonal mPCs and computed the P value based on a chi-squared distribution with 439 degrees of freedom. We computed P values using a one-sided test, analogous to how in linear regression, one-sided chi-squared test statistics are computed (corresponding to two-sided tests of z-statistics).

MDMR of oral microbiomes with selected genetic variants

We compared our test for genetic effects on oral microbiome composition with multivariate distance matrix regression (MDMR)33 as implemented in the MDMR R package36 (v.0.5.2), which finds significant predictors of multivariate outcomes by estimating the attributable amount of dissimilarity between samples. Rank-based inverse normal transformed relative abundances of the 439 most prevalent species (with or without initial centred log-ratio transformation) were used to generate the Euclidean distance matrix. MDMR was then run with the following covariates: sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex and percentage of mapped reads. As genetic ancestry PCs frequently produced a singular matrix as a result of multicollinearity with individual variants, the top ten genetic PCs were first regressed from each tested variant (rather than including genetic PCs as covariates). The 11 loci identified from our mPC-based GWAS of oral microbiome composition were tested alongside 1,000 randomly selected variants on chromosome 1.

Stratified LD score regression for estimating enrichment of heritability at genes with tissue-specific expression

We observed that the same mathematical framework that enables partitioning of heritability by means of stratified LD score regression on summary statistics from GWAS of a single trait74 could be extended to analyse test statistics for association with oral microbiome composition (based on summing chi-squared test statistics across 439 mPCs). Starting from the representation of expected marginal chi-square association statistic for SNP i based on linkage disequilibrium with variants in categories Ck,

averaging across the 439 chi-square statistics for each variant gives

such that providing \(\bar{{\chi }_{i}^{2}}\) as input to S-LDSC generates enrichments corresponding to \(\bar{{\tau }_{k}}\). Averaged chi-square statistics per variant were used as input to munge_sumstats.py. LDSC was then run with baseline v.1.2, weights_hm3_no_hla as weights and previously described tissue-specific expression bins derived from Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project samples37.

GWAS of abundances of individual taxa

To avoid test statistic inflation from zero inflation and outlier values, relative abundance measures for each taxon were rank-based inverse normal transformed. Abundances of 1,262 taxa (of any phylogenetic level: species, genus, family and so on) observed in >10% of SPARK samples were then tested for association with host genotypes using BOLT-LMM. The top 20 PCs from PCA on 439 species observed at >10% prevalence (that is, the top 20 mPCs) were used as covariates to control for the largest axes of variation across samples, along with sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex, percentage of mapped reads and the top ten genetic ancestry PCs. To test loci that might be associated as dominant/recessive rather than additive, BOLT-LMM was rerun using the --domRecHetTest flag.

To evaluate whether some of these associations could reflect compositional effects rather than being specific to the associated taxa, we computed an alternative set of taxon abundance phenotypes in which we took the centred log-ratio transform of relative abundances in each sample75 (after replacing zero values observed for a given taxon with the minimum non-zero value for that taxon, to allow computing geometric means). Centred log-ratio transformed values for each taxa were then tested for association with host genotypes using BOLT-LMM with the same covariates as above (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

For estimating effect sizes of specific genotype values such as FUT2 W154X genotypes (Fig. 2d), AMY1 copy numbers (Fig. 3c) or PRB1 copy numbers (Extended Data Fig. 3c), we used linear regression with the same covariates as above, encoding each genotype value (rounded if necessary) as a separate factor. The standard errors estimated by these regressions are slightly underestimated because they do not account for relatedness among SPARK participants, but we determined that this underestimation of standard errors was mild (~7% based on a ~14% inflation of chi-square test statistics computed using linear regression versus a linear mixed model for the 11 genome-wide significant loci (Supplementary Fig. 2)). To compare effect sizes in adults versus unrelated children, one child was randomly selected from each family in SPARK. BOLT-LMM was used to run linear regression on each of these subsets separately.

GWAS in UK Biobank

Starting from 488,377 individuals in the UKB SNP-array dataset43, individuals were excluded on the basis of the following criteria: 36,008 were removed to drop one relative in pairs of close relatives with kinship coefficient >0.0884, preferentially keeping individuals if they (1) reported having dentures or (2) reported not having dentures (that is, had a non-missing dentures phenotype); 28,701 were removed for not having European genetic ancestry76; 1,469 were removed for not having available TOPMed-imputed genotypes (including for chromosome X); 2,601 were removed for not having available WGS data; and 53 were removed for having withdrawn, leaving 419,545 available individuals for GWAS. For the binary oral health phenotypes (dentures use and bleeding gums), 418,039 had non-missing values. For the quantitative BMI z-score phenotype77, 418,150 had non-missing values.

TOPMed-imputed variants for these individuals were filtered to require minor allele frequency >0.001 and INFO >0.3. BOLT-LMM was run in linear regression mode on these samples and variants with the following covariates: age, age squared, sex, genotype array, assessment centre and top 20 genetic ancestry PCs. For estimating effect sizes of specific copy numbers of AMY1 (Fig. 3d,e,j), AMY2A (Extended Data Fig. 6f) or AMY2B (Extended Data Fig. 6g), we performed logistic regression (for oral health phenotypes) or linear regression (for BMI) with the same covariates, encoding each copy number (rounded to the nearest integer) as a separate factor and using the modal copy number as the reference level.

Phyletic stratification of genetic associations

The phylogenetic tree of all species in the MetaPhlAn 4 database used (v.Oct22), mpa_vOct22_CHOCOPhlAnSGB_202212.nwk, was first subsetted to the tree spanning nodes with primary label among the 439 species seen at >10% prevalence in the SPARK cohort. This tree was used with graphlan (v.1.1.3) for depiction of phylogenetic trees (Figs. 1b and 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5f). For comparisons among the effect sizes of a human genetic variant associated with relative abundances of many species, phylogenetic distances between pairs of species were first computed as a cophenetic distance matrix from this tree. For a given index species A, phylogenetic distances between A and other species B were then compared with either (1) absolute values of effect sizes for species B (that is, |βB|, Extended Data Fig. 5b,c,g,h) or (2) effect sizes for species B oriented relative to the effect direction for species A (that is, sign(βA) × βB, Extended Data Fig. 5d,e,i,j).

Estimation of AMY1 copy number in all cohorts

In the SPARK (Extended Data Fig. 6a) and AoU v7 cohorts (Extended Data Fig. 6c), AMY1 copy number was estimated by counting WGS reads that mapped to the duplicated regions that include AMY1A (chr. 1: 103638545–103666411), AMY1B (chr. 1: 103685558–103713427) and AMY1C (chr. 1: 103732687–103760549) in GRCh38 and normalizing against the total number of reads that aligned in either the 0.5 Mb upstream of AMY2B or the 0.5 Mb downstream of AMY1C. For the UKB cohort (n = 490,415 (ref. 78), Fig. 3a), we applied a more comprehensive read-depth normalization pipeline that incorporated sample-specific GC-bias correction inferred from genome-wide alignments (similar to Genome STRiP79) before normalizing against read depth in the 0.5 Mb regions flanking the amylase locus. We corrected for slight miscalibration of these diploid copy number estimates by fitting a linear model to identify coefficients that centred peaks of copy number estimates at integers.

Among the UKB participants with WGS available, we identified 5,149 siblings that shared both amylase haplotypes IBD2 (based on at most three mismatching SNP-array genotypes in a 2 Mb window flanking the amylase locus, computed using plink1.9 --genome). Among these IBD2 sibling pairs, 13 pairs were identified as copy number discordant (and likely to reflect a copy number mutation in the past generation) based on (1) having AMY1 copy number estimates that differed by >1.0 and (2) having AMY2A copy number estimates consistent with a duplication or deletion of a commonly variable amylase gene cassette (that is, ±1 AMY2A copies for AMY1 copy number discordances of odd parity and no difference in AMY2A copy number for AMY1 copy number discordances of even parity). We estimated AMY1 copy number genotyping accuracy by computing the correlation across IBD2 sibling pairs excluding these 13 copy number discordant pairs.

Testing AMY1 copy number for association with dental phenotypes and BMI in All of Us

We defined the binary tooth loss phenotype as 1 for individuals with at least one recorded instance of ‘acquired absence of all teeth’ (OMOP concept ID: 40481327, code: 441935006) and 0 otherwise. Likewise, the caries phenotype was derived from ‘dental caries’ (OMOP concept ID: 133228, code: 80967001). For BMI, we generated a normalized z-score phenotype from BMI (OMOP concept ID: 903124, code: bmi) by first adjusting for age (in months, determined from time at weight and height measurement) and age squared and then applying inverse rank normal transformation in each sex separately. The BMI z-scores for males and females were then merged together.

Individuals with WGS available for genotyping AMY1 copy number were first filtered to an unrelated subset of samples (iteratively dropping one individual per related pair with kinship score >0.1, from relatedness_flagged_samples.tsv). For oral health phenotypes, we performed logistic regression against AMY1 copy number including age, age squared, sex and the top 16 genetic ancestry PCs (from ancestry_preds.tsv) as covariates. For BMI, we performed linear regression using only genetic ancestry PCs as covariates as age and sex had already been residualized out. For estimating effect sizes of specific copy numbers of AMY1 (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e and Extended Data Fig. 7f–i), we performed logistic regression (for oral health phenotypes) or linear regression (for BMI) with the same covariates, encoding each copy number (rounded to the nearest integer) as a separate factor and using the modal copy number of 6 as the reference level (that is, computing the effect size of each copy number relative to copy number 6).

Paralogous sequence variation in AMY1

To identify and genotype paralogous sequence variants (PSVs) from UKB WGS data, we used a read-counting approach similar to our previous work80. In brief, reads from each sample that had been aligned to any of the three 27.6 kb regions in GRCh38 corresponding to AMY1A (chr. 1: 103638695–103666261), AMY1B (chr. 1: 103685708–103713277) and AMY1C (chr. 1: 103732837–103760399) were realigned with bwa (v.0.7.17) to the reference sequence of AMY1A after filtering out reads with any of the last four SAM flags (-F 0xF00). Read counts supporting each base at each position were tabulated with htsbox (r345) pileup, filtering alignments <50 bp and base calls with quality score <20. Individuals were called heterozygous for a PSV allele (having at least one copy of AMY1 with each of two alleles) if at least five reads supported the variant allele in that sample and at least five reads did not. PSVs were then filtered to those with heterozygosity >0.002 (resulting in 892 PSVs passing filters). To estimate diploid copy number genotypes for a PSV, we multiplied each individual’s diploid AMY1 copy number by the allelic fraction of the PSV in that individual. In association tests using linear regression with BOLT-LMM, we rounded copy number estimates to integer genotypes.

For follow-up analyses of effect sizes of specific AMY1 F141C and C477R copy number genotypes, we optimized the assignments of integer copy number genotypes based on manual inspection of histograms of allelic depth-derived PSV copy number estimates (Supplementary Fig. 3). Specifically, we assigned copy numbers for each of F141C and C477R using the thresholds [0,0.25) = CN0, [0.25,1.75) = CN1, [1.75,2.7) = CN2, [2.7,3.5) = CN3 and [3.5,5) = CN4. In UKB, F141C had 416,381 (99.2%), 3,124 (0.74%) and 40 (0.0095%) individuals with 0, 1 and 2 copies, respectively, and C477R had 412,450 (98.3%), 6,527 (1.6%), 547 (0.13%), 19 (0.0045%) and 2 (0.0005%) individuals with 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 copies, respectively. In SPARK, F141C had 12,459 (99.5%) and 60 (0.48%) individuals with 0 and 1 copies, respectively, and C477R had 12,343 (98.6%), 172 (1.4%) and 4 (0.032%) individuals with 0, 1 and 2 copies, respectively. These threshold-based copy numbers of the alternate alleles were used in logistic regression along with copy numbers of the reference alleles (F141 and C477) and covariates as above.

Protein expression of AMY1

Plasmid pCAGEN81 was a gift from C. Cepko (Addgene plasmid no. 11160; http://n2t.net/addgene:11160; RRID Addgene_11160). Codon-optimized sequences encoding reference, F141C and C477R AMY1 alleles were synthesized and ordered as gBlocks from Integrated DNA Technologies for cloning into pCAGEN downstream of the CAG promoter. Clones were screened for sequence errors before plasmid preparation using Plasmid Plus Midi Kit (Qiagen, catalogue no. 12943). Plasmid pUC19 (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. N3041S) was used as a negative control. A total of 15 µg of each plasmid was lipofected into separate 10 cm plates of HEK293T (Takara, catalogue no. 632180) cells at ~70% confluence using 30 µl of Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, catalogue no. L3000015). Authentication of HEK293T was done by morphological match for type and verification of SV40T antigen with PCR assay. Lack of mycoplasma contamination was confirmed by Takara as well as inhouse with MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, catalogue no. LT07-318). Medium was switched to serum-free after 24 h before collection of both supernatant and lysate at 72 h post-lipofection. A total of 10 ml of supernatant was spun at 1,000g for 10 min to remove cells and debris before the addition of 100 µl of Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100×, Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. 78438) and 100 µl of EDTA (0.5 M). Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS before the addition of cold 1 ml of RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. 89900) with 10 µl of Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100×) and 10 µl of EDTA (0.5 M). After sufficient solubilization of the cells had occurred, 1 µl of Benzonase Nuclease (250 U per µl, Milipore, catalogue no. E1014) and 10 µl of MgCl2 (1 M) were added before incubation at 37 °C, 500 rpm for 30 min. Lysate was then spun at 10,000g for 10 min to remove insoluble precipitate. Both supernatant and lysate were stored at −80 °C until further use.

Western blot of AMY1 in cell culture supernatant and lysate

A total of 7.5 µl of supernatant or purified lysate was first run denatured and reduced in a 10% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gel (Bio-Rad, catalogue no. 4561036) before wet transfer to nitrocellulose membrane (120 V, 2 h). After evaluation of equal loading by Ponceau S Staining Solution (Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. A40000279), the membrane was blocked for 1 h at room temperature with TBS, 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% w/v non-fat dry milk before washing three times for 5 min each with TBS-T (TBS, 0.1% Tween-20). Amylase antibody (G-10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalogue no. sc-46657, lot no. G0324) was used as the primary antibody at a 1:200 dilution in TBS-T with 5% w/v milk for incubation overnight at 4 °C with rotation. Membrane was washed three times for 5 min each with TBS-T before addition of anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, catalogue no. 7076, lot no. 39) as secondary at a 1:2,000 dilution in TBS-T with 5% w/v milk for 1 h incubation at room temperature with rotation. Membrane was washed three times for 5 min each with TBS-T before detection with Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Cytiva, catalogue no. RPN2236) (Extended Data Fig. 7a).

Purification of AMY1 reference and F141C protein

Purification of amylase from supernatant was done using glycogen, adapted from refs. 82,83. All following steps were conducted on ice or at 4 °C (rotation and centrifugation). In brief, 10 ml of supernatant was initially concentrated using prewet 15 ml Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter, 30 kDa MWCO (Milipore, catalogue no. UFC9030) and put up to a total volume of 900 µl with PBS. A total 600 µl of cold ethanol was added slowly to make 40% ethanol v/v. This was then centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min to remove any insoluble precipitate. To the supernatant, 75 µl of 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8), 75 µl of glycogen (20 mg ml−1, Roche, catalogue no. 10901393001) and 100 µl of ethanol were added in that order. This was then incubated for 5 min with end-over-end mixing before centrifugation at 5,000g for 6 min. The glycogen pellets were then washed twice with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8) containing ethanol (40% v/v) before resuspension in 100 µl of 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7, Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. J61821-AK) with 5 mM CaCl2. These were then incubated at 37 °C, 500 rpm for 30 min to allow for glycogen digestion. The above purification procedure was repeated as necessary to arrive at purified amylase as evaluated on 10% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gel with InstantBlue Coomassie Protein Stain (Abcam, catalogue no. ab119211) (Extended Data Fig. 7b).

Amylase activity assay

Protein was normalized between reference and F141C isoforms by densitometric measurement against linear dilution series (r2 = 0.99 with input). The concentration chosen for the assay was determined by having maximal linear activity over the observation window. For each technical replicate, 10 µl of reference or F141C amylase enzyme diluted in 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7), 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.02% w/v BSA (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. B9000) was quickly mixed with 10 µl of BODIPY FL conjugated-starch substrate from EnzChek Ultra Amylase Assay Kit (Invitrogen, catalogue no. E33651) in 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7) with 5 mM CaCl2. The reaction was then maintained at 20 °C for 2 h in a Bio-Rad CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection System with fluorescence reading taken every minute using FAM fluorophore settings with CFX Manager (v.3.1) software. Fluorescence at 30 min relative to initial reading was used as input to a linear model with allele and plate to regress out any run-to-run effects during comparison across technical replicates (Extended Data Fig. 7c).

Bacterial genome reference panel for analysing bacterial gene dosages

To reduce hypothesis testing burden in association analyses of human genetic variants with bacterial gene dosage phenotypes, we restricted analyses to a set of 30 bacterial genomes representing highly abundant species and species whose abundances we had found to associate with human genetic variants. Specifically, we selected 30 bacterial species with genomes available in GenBank by including: (1) the five most abundant species in SPARK oral microbiomes, (2) species that associated strongly (P < 4 × 10−11) with at least one human genetic variant and (3) the top two associated species for each locus if not already included. We substituted Stomatobaculum longum for the related Stomatobaculum SGB5266 which would have been included under (2) but lacked a GenBank assembly. We selected a single genome for each of the 30 species using the following criteria. The SGB centroid was prioritized over other genomes if it corresponded to a GenBank assembly. For cases in which the centroid was not a GenBank assembly and multiple genomes corresponded to GenBank assemblies, the reference genome was prioritized if available, or otherwise the highest ranked genome among those listed. A list of these species and GenBank assemblies is included in Supplementary Table 6. A bowtie2 index was then built from these merged genomes.

Measuring bacterial gene dosages using read-depth phenotypes

We computed WGS coverage-derived phenotypes informative of gene dosage across each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes by first realigning unmapped reads from SPARK saliva WGS to the 30 reference genomes using bowtie2 (v.2.5.1) with the --very-sensitive flag. These alignments were then position-sorted within contigs with samtools (v.1.15.1). For each WGS sample, we quantified read depth in 500 bp bins tiling each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes using mosdepth (v.0.3.6), excluding reads with mapping quality <5. For each sample, for each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes, we then median-normalized the bin-level read-depth measurements across the 500 bp bins of that reference genome to control for species abundance (such that normalized read-depth measurements had a median of 1 among bins corresponding to each species). If a sample had <0.5× median coverage across bins corresponding to a given species, we set that sample’s normalized read-depth measurements for that species to missing to focus downstream analyses on samples with less-noisy measurements. Finally, we truncated median-normalized read-depth values to the interval [0,1], both to focus on deletions in bacterial genomes and to reduce the influence of outlier measurements that might reflect mismapped reads (potentially derived from either duplicated genomic regions or homologous sequences in microbial species not represented among the 30 reference genomes). We reasoned that these bin-level measurements would capture kilobase-scale deletions of bacterial genomes, circumventing the need to predefine a set of structural variant regions (which was difficult because of the limited sequencing coverage of most species). Additional details are provided in Supplementary Note 5.

Testing bacterial gene dosage phenotypes for association with host genotypes

We used linear regression to test each of the 11 human genetic variants we had found to associate with oral microbiome composition (Extended Data Table 1) for association with normalized read depth (truncated to [0,1]) in each 500 bp bin of each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes. We used an additive model for all variants except FUT2 W154X and TLR1 I602S, for which we used a recessive model (corresponding to secretor/non-secretor status for FUT2). We took two precautions to avoid potential confounders. First, for each of the 30 species, we included as covariates the top 20 PCs of the normalized, truncated read-depth matrix for that species (running PCA after centring and scaling each bin to have a mean of 0 and s.d. of 1 across samples) to control for linked gene dosages (for example, differences across strains) that could potentially generate non-causal associations in a manner analogous to population structure in GWAS (Supplementary Note 5). Second, we applied a form of genomic control84 (applied across the 500 bp bins of each reference genome) to adjust for remaining test statistic inflation. Specifically, for each pairing of a species and a human genetic variant, we computed the adjustment factor

across the \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) test statistics for the 500 bp bins of that reference genome, where F−1(x) is the inverse cumulative distribution function for a \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) random variable. The \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) test statistics were then divided by this factor. This yielded 208 read-depth bins in 18 species that significantly associated with at least one of the 11 human genetic variants (FDR < 0.01, Supplementary Tables 7 and 8) and resolved to 68 unique microbial regions after merging bins within 1.5 kb of another significantly associated bin (Fig. 4b). We verified that the truncated normalized read-depth phenotypes involved in these associations were broadly reasonably distributed (with most bimodal at 0 and 1 and mean between 0.05 and 0.95; Supplementary Table 7), such that testing these phenotypes for association with common variants (MAF = 0.08–0.45) using linear regression in a cohort of size 12,519 was expected to produce robust test statistics77.

For combinatorial analysis of deletions of the five vad genes in V. sp. 3627 that associated in the same direction with FUT2 genotype (vadB through vadF) (Fig. 6e), we first selected individuals whose oral microbiomes had evidence of near-complete presence (>0.8 median-normalized coverage) or near-complete absence (<0.2 median-normalized coverage) of each vad gene (n = 3,081, representing roughly half of the SPARK samples with coverage of the V. sp. 3627 genome reaching the >0.5× threshold for analysis). For each common combination (>2.5% of selected individuals) of presence/absence status of vadB through vadF, the number of individuals with each FUT2 W154X genotype were then counted.

Replication of bacterial gene dosage associations in the All of Us cohort

To evaluate the generalizability of the associations we identified in SPARK between human genetic variants and bacterial gene dosages, we applied the same computational pipeline described above to 10,000 randomly selected saliva-derived WGS samples from the AoU v.8 data release. We then attempted to replicate the 208 associations (between human genetic variants and normalized read-depth measurements in 500 bp bins of bacterial genomes) that had reached significance (FDR < 0.01) in SPARK.

AlphaFold3 prediction of protein structures

To predict protein structures for Streptococcus parasanguinis AbpA or AbpB (bound to human AMY1), the Veillonella sp. 3627 VadD trimer and Streptococcus mitis CrpE, we used AlphaFold3 (ref. 85) for multimer prediction with default reference databases and max template date of 2021-09-29. The TonB domain of AbpB and the signal peptide of VadD were excluded for visualization. To minimize the model size, CrpE was truncated to the region spanning the CshA NR2 domain to the sixth mucin-binding domain (residues 572–2701). Structures were visualized with ChimeraX (v.1.9)86 and pLDDT, pTM and ipTM values can be found in Supplementary Table 9.

Genetically derived blood typing in SPARK

We assigned blood types to SPARK participants on the basis of WGS-derived SNP and indel genotypes using a procedure similar to previous work12. The genotype of the rs8176746 missense SNP was first used to determine an individual’s dosage (that is, allele count) of type B alleles (T allele count) and non-type B dosage (G allele count).

The rs8176719 indel was next used to determine type O1 dosage (deletion allele count), which was subtracted from the non-type B dosage to yield non-type B/O1 dosage, as the rs8176719 deletion allele typically occurs on haplotypes that would otherwise be type A alleles. Although this is true in European, East Asian and American ancestry haplotypes in 1KGP populations, in a small fraction of African (3.2%) and South Asian (0.2%) ancestry haplotypes, the rs8176719 deletion occurs in cis with the type B missense allele. As we found 36 SPARK participants who had O1 dosage exceeding non-type B dosage, we subtracted this excess from their type B dosages.

The rs41302905 missense SNP was next used to determine type O2 dosage (T allele count) and subtracted from the non-type B/O1 dosage to yield type A dosage, as it seems to be in cis with type A alleles in all 1KGP populations. O1 and O2 dosages were then merged to compute type O dosage.

The rs56392308 indel was next used to determine the type A2 dosage (deletion allele count) and subtracted from the type A dosage to yield type A1 dosage. For seven individuals in which the type A2 dosage exceeded type A dosage, five seemed to be on type O alleles and two on either type O or type B alleles, so this excess was subtracted from their type A2 dosage.

Enrichment of conserved domains in bacterial genes associated with secretor status

For each of the bacterial species with adhesin genes in dosage variable regions that associated with FUT2 loss of function (Fig. 6a–c,f,g), protein IDs (WP numbers) for the species were extracted from its RefSeq general feature format (GFF) file. Conserved domains (from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) conserved domain database) were identified for each protein using a modified version of the provided bwrpsb.pl script (applied to up to 250 proteins at a time). A one-sided Fisher’s exact test was used to identify domains enriched among proteins encoded by genes within read-depth bins that associated with FUT2 genotype.

GWAS of read depth in selected microbial genomic regions

We used BOLT-LMM to perform GWAS on the five normalized read-depth phenotypes for which we observed the most significant associations with human genetic variants (in our targeted analysis of 11 human genetic variants). Specifically, these phenotypes measured WGS read depth in the following 500 bp bins: H. sputorum QEQH01000003.1: 197,000–197,500, P. nanceiensis KB904333.1: 123,500–124,000, S. mitis MUYN01000003.1: 100,000–100,500, S. vestibularis AEKO01000011.1: 186,000–186,500, V. sp. 3627 RQVG01000009.1: 13,500–14,000. In each GWAS, we included as covariates the top 20 PCs of the normalized, truncated read-depth matrix for the species under consideration, along with sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex, percentage of mapped reads and the top ten human genetic PCs.