Abstract

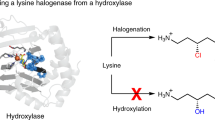

Terminal alkyne-containing natural products can undergo the bio-orthogonal ‘click’ reaction of Cu(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition. Recently, an enzymatic mechanism for terminal alkyne formation was discovered in the biosynthesis of l-β-ethynylserine where the pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme BesB forms a rare terminal alkyne-containing amino acid, l-propargylglycine, from a vinyl halide precursor, 4-chloro-l-allylglycine. Here we present the 1.3-Å-resolution crystal structure of BesB with detailed mechanistic and computational studies. We demonstrate that BesB can reversibly catalyze the exchange of the halogen in various 4-halo-allyl-l-glycines, implying the existence of an allene intermediate, which we then also observe. Taken together, this work supports a mechanism whereby an allene is formed from deprotonation-driven halogen loss and the terminal alkyne is then formed by isomerization of the allene. Our work further expands our understanding of the catalytic repertoire of pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzymes and will enable development of metal-free allene-forming and alkyne-forming biocatalysts.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this work are available in the article and its Supplementary Information. The crystallographic data were deposited to the PDB under accession codes 9AUA and 9AUB. Data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Dorel, R. & Echavarren, A. M. Gold(I)-catalyzed activation of alkynes for the construction of molecular complexity. Chem. Rev. 115, 9028–9072 (2015).

Kuklev, D. V., Domb, A. J. & Dembitsky, V. M. Bioactive acetylenic metabolites. Phytomedicine 20, 1145–1159 (2013).

Kolb, H. C., Finn, M. G. & Sharpless, K. B. Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 2004–2021 (2001).

Thirumurugan, P., Matosiuk, D. & Jozwiak, K. Click chemistry for drug development and diverse chemical–biology applications. Chem. Rev. 113, 4905–4979 (2013).

Minto, R. E. & Blacklock, B. J. Biosynthesis and function of polyacetylenes and allied natural products. Prog. Lipid Res. 47, 233–306 (2008).

Reed, D. W. et al. Mechanistic study of an improbable reaction: alkene dehydrogenation by the Δ12 acetylenase of Crepis alpina. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 10635–10640 (2003).

Gagné, S. J., Reed, D. W., Gray, G. R. & Covello, P. S. Structural control of chemoselectivity, stereoselectivity, and substrate specificity in membrane-bound fatty acid acetylenases and desaturases. Biochemistry 48, 12298–12304 (2009).

Jeon, J. E. et al. A pathogen-responsive gene cluster for highly modified fatty acids in tomato. Cell 180, 176–187.e19 (2020).

Haritos, V. S. et al. The convergent evolution of defensive polyacetylenic fatty acid biosynthesis genes in soldier beetles. Nat. Commun. 3, 1150 (2012).

Zhu, X., Liu, J. & Zhang, W. De novo biosynthesis of terminal alkyne-labeled natural products. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 115–120 (2015).

Zhu, X., Su, M., Manickam, K. & Zhang, W. Bacterial genome mining of enzymatic tools for alkyne biosynthesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 10, 2785–2793 (2015).

Ross, C., Scherlach, K., Kloss, F. & Hertweck, C. The molecular basis of conjugated polyyne biosynthesis in phytopathogenic bacteria. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7794–7798 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Discovery of a dual function cytochrome P450 that catalyzes enyne formation in cyclohexanoid terpenoid biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 13537–13541 (2020).

Lv, J. et al. Biosynthesis of biscognienyne B involving a cytochrome P450‐dependent alkynylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 13531–13536 (2020).

Li, X., Lv, J.-M., Hu, D. & Abe, I. Biosynthesis of alkyne-containing natural products. RSC Chem. Biol. 2, 166–180 (2021).

Nakamura, H., Matsuda, Y. & Abe, I. Unique chemistry of non-heme iron enzymes in fungal biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Prod. Rep. 35, 633–645 (2018).

Rudolf, J. D., Chang, C.-Y., Ma, M. & Shen, B. Cytochromes P450 for natural product biosynthesis in Streptomyces: sequence, structure, and function. Nat. Prod. Rep. 34, 1141–1172 (2017).

Marchand, J. A. et al. Discovery of a pathway for terminal-alkyne amino acid biosynthesis. Nature 567, 420–424 (2019).

Du, Y.-L. & Ryan, K. S. Pyridoxal phosphate-dependent reactions in the biosynthesis of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 430–457 (2019).

Ferla, M. P. & Patrick, W. M. Bacterial methionine biosynthesis. Microbiology 160, 1571–1584 (2014).

Nakashima, N. & Tamura, T. Isolation and characterization of a rolling-circle-type plasmid from Rhodococcus erythropolis and application of the plasmid to multiple-recombinant-protein expression. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5557–5568 (2004).

Du, Y.-L., Dalisay, D. S., Andersen, R. J. & Ryan, K. S. N-Carbamoylation of 2,4-diaminobutyrate reroutes the outcome in padanamide biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 20, 1002–1011 (2013).

Shen, W., Borchert, A. J. & Downs, D. M. 2-Aminoacrylate stress damages diverse PLP-dependent enzymes in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 101970 (2022).

Aitken, S. M., Lodha, P. H. & Morneau, D. J. K. The enzymes of the transsulfuration pathways: active-site characterizations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814, 1511–1517 (2011).

Aitken, S. M. & Kirsch, J. F. The enzymology of cystathionine biosynthesis: strategies for the control of substrate and reaction specificity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433, 166–175 (2005).

Clausen, T., Huber, R., Laber, B., Pohlenz, H.-D. & Messerschmidt, A. Crystal structure of the pyridoxal-5′-phosphate dependent cystathionine β-lyase from Escherichia coli at 1.83 Å. J. Mol. Biol. 262, 202–224 (1996).

Clausen, T., Huber, R., Prade, L., Wahl, M. C. & Messerschmidt, A. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli cystathionine γ-synthase at 1.5 Å resolution. EMBO J. 17, 6827–6838 (1998).

Liang, J., Han, Q., Tan, Y., Ding, H. & Li, J. Current advances on structure-function relationships of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 6, 4 (2019).

Walsh, C. T. & Abeles, R. H. Acetylenic enzyme inactivators. Inactivation of γ-cystathionase, in vitro and in vivo, by propargylglycine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 6124–6125 (1973).

Washtien, W. & Abeles, R. H. Mechanism of inactivation of γ-cystathionase by the acetylenic substrate analogue propargylglycine. Biochemistry 16, 2485–2491 (1977).

Johnston, M. et al. Suicide inactivation of bacterial cystathionine γ-synthase and methionine γ-lyase during processing of l-propargylglycine. Biochemistry 18, 4690–4701 (1979).

Esaki, N. et al. Mechanism-based inactivation of l-methionine γ-lyase by l-2-amino-4-chloro-4-pentenoate. Biochemistry 28, 2111–2116 (1989).

Sun, Q. et al. Structural basis for the inhibition mechanism of human cystathionine γ-lyase, an enzyme responsible for the production of H2S. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3076–3085 (2009).

Kobayashi, M. et al. Simplification of FDLA pre-column derivatization for lc/ms/ms toward separation and detection of d,l-amino acids. Chromatographia 82, 705–708 (2019).

Krause, N. & Hoffmann-Röder, A. in Modern Allene Chemistry (eds Krause, N. & Hashmi, A. S. K.) Ch. 18 (Wiley, 2004).

Hatanaka, S.-I., Niimura, Y., Takishima, K. & Sugiyama, J. (2R)-2-Amino-6-hydroxy-4-hexynoic acid, and related amino acids in the fruiting bodies of Amanita miculifera. Phytochemistry 49, 573–578 (1998).

Dautermann, O. et al. An algal enzyme required for biosynthesis of the most abundant marine carotenoids. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw9183 (2020).

Hoegl, A. et al. Mining the cellular inventory of pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzymes with functionalized cofactor mimics. Nat. Chem. 10, 1234–1245 (2018).

Du, Y.-L. et al. A pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme that oxidizes an unactivated carbon–carbon bond. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 194–199 (2016).

Barra, L. et al. β-NAD as a building block in natural product biosynthesis. Nature 600, 754–758 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. A pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent Mannich cyclase. Nat. Catal. 6, 476–486 (2023).

Inoue, H. et al. Role of tyrosine 114 of l-methionine γ-lyase from Pseudomonas putida. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64, 2336–2343 (2000).

Astegno, A., Allegrini, A., Piccoli, S., Giorgetti, A. & Dominici, P. Role of active-site residues Tyr55 and Tyr114 in catalysis and substrate specificity of Corynebacterium diphtheriae C-S lyase. Proteins 83, 78–90 (2015).

Anufrieva, N. V. et al. The role of active site tyrosine 58 in Citrobacter freundii methionine γ-lyase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1854, 1220–1228 (2015).

Brzovic, P., Litzenberger Holbrook, E., Greene, R. C. & Dunn, M. F. Reaction mechanism of Escherichia coli cystathionine γ-synthase: direct evidence for a pyridoxamine derivative of vinylglyoxylate as a key intermediate in pyridoxal phosphate dependent γ-elimination and γ-replacement reactions? Biochemistry 29, 442–451 (1990).

Yee, D. A. et al. Genome mining of alkaloidal terpenoids from a hybrid terpene and nonribosomal peptide biosynthetic pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 710–714 (2020).

Hai, Y., Chen, M., Huang, A. & Tang, Y. Biosynthesis of mycotoxin fusaric acid and application of a PLP-dependent enzyme for chemoenzymatic synthesis of substituted l-pipecolic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19668–19677 (2020).

Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. W. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D 67, 271–281 (2011).

Evans, P. R. & Murshudov, G. N. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D 69, 1204–1214 (2013).

Terwilliger, T. C. et al. Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: the PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D 65, 582–601 (2009).

Terwilliger, T. C. et al. Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D 64, 61–69 (2008).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Afonine, P. V. et al. Joint X-ray and neutron refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 1153–1163 (2010).

Moriarty, N. W., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W. & Adams, P. D. electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. D 65, 1074–1080 (2009).

Martínez-Rosell, G., Giorgino, T. & De Fabritiis, G. PlayMolecule ProteinPrepare: a web application for protein preparation for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 57, 1511–1516 (2017).

Lee, T.-S. et al. GPU-accelerated molecular dynamics and free energy methods in AMBER18: performance enhancements and new features. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 2043–2050 (2018).

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

Bayly, C. I., Cieplak, P., Cornell, W. & Kollman, P. A. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: the RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 10269–10280 (1993).

Singh, U. C. & Kollman, P. A. An approach to computing electrostatic charges for molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 5, 129–145 (1984).

Besler, B. H., Merz, K. M. & Kollman, P. A. Atomic charges derived from semiempirical methods. J. Comput. Chem. 11, 431–439 (1990).

Li, P., Roberts, B. P., Chakravorty, D. K. & Merz, K. M. Rational design of particle mesh Ewald compatible Lennard–Jones parameters for +2 metal cations in explicit solvent. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 2733–2748 (2013).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983).

Joung, I. S. & Cheatham, T. E. Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 9020–9041 (2008).

Maier, J. A. et al. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side hain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3696–3713 (2015).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993).

Roe, D. R. & Cheatham, T. E. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 3084–3095 (2013).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Becke, A. D. Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Chai, J.-D. & Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6615–6620 (2008).

Cossi, M., Rega, N., Scalmani, G. & Barone, V. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 669–681 (2003).

Li, L., Li, C., Zhang, Z. & Alexov, E. On the dielectric ‘constant’ of proteins: smooth dielectric function for macromolecular modeling and its implementation in DelPhi. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 2126–2136 (2013).

Schutz, C. N. & Warshel, A. What are the dielectric ‘constants’ of proteins and how to validate electrostatic models? Proteins 44, 400–417 (2001).

Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J.-M. & Brenner, S. E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2021-02626 to K.S.R.), the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM134271 to M.C.Y.C.), the National Science Foundation (CLP-2204014 to M.C.Y.C.), the Spanish MICINN (PID2022-141676NB-I00 and TED2021-130173B-C42 projects and RYC2020-028628-I fellowship to M.G.-B.) and the Generalitat de Catalunya AGAUR (2021SGR00623 project to M.G.-B.). J.A.M. would like to thank the HHMI Gilliam Fellowship for support. C.C.-T. is supported by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Schmidt Futures program. Some of the computational resources used were funded by FEDER and Spanish MINECO through projects CTQ2014-54306-P, CTQ2015-69363-P and MPCUdG2016/096 and by the European Research Council under the European Union’s ERC-StG-2015 (grant agreement 679001). We are grateful to the Canadian Light Source for access to beamline CMCF-BM and to the SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, for access to beamline 9-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B.H. carried out the structural and biochemical studies on SAcBesB. J.A.M. and D.C.M. carried out the biochemical studies on SSpBesB and SCaBesB and synthesized compound 5. C.C.-T. carried out the computational studies. Z.-W.W. carried out the kinetic analysis. M.G.-B. directed the computational studies, M.C.Y.C. directed the biochemical studies and K.S.R. directed the structural and biochemical studies. J.B.H., J.A.M., C.C.-T., M.G.-B., M.C.Y.C. and K.S.R. prepared the paper with feedback from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Yang Hai, Francesco Marchesani, Riccardo Miggiano, Andrea Mozzarelli, Darrin York and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Biosynthetic routes to internal alkyne-containing natural products.

a) Terminal alkynes can be synthesized using non-heme diiron-dependent enzymes. Similar non-heme diiron-dependent enzymes also catalyzed the formation of internal alkyne moieties found in several polyacetylenic fatty acids. Crep16 and Crep1-like desaturases have been characterized in the biosynthesis of crepenynic acid7, falcarindiol8, and dihydromatricaria acid9. b) An additional pathway to form alkynes has been discovered for the biosynthesis of the 1,3-enyne-containing cyclohexanoids, which are generated by P450-dependent oxidases such as AtyI and BisI, in the biosynthesis of asperpentyn13 and biscognienyne B14, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Purification and activity data for SAcBesB.

a) Propargylglycine biosynthetic gene cluster in S. achromogenes. b) SDS-PAGE gel of purified SAcBesB. c) Gel filtration data for SAcBesB. Protein standards for alcohol dehydrogenase, bovine serum albumin, and carbonic anhydrase indicated. d) Compound 3 production by SAcBesB using 1 as a substrate. e) Compound 3 production by SAcBesB using 2 as a substrate. Reactions repeated in triplicate with representative results shown.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Kinetics of the SAcBesB reaction.

Steady state kinetic analysis of BesB with respect to its substrate 4-chloroallylglycine (1). Each chosen concentration (20 μM to 2 mM) of 1 was performed in triplicate. Data points were subjected to non-linear curve fitting to Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain the kinetic parameters kcat = 0.0228 ± 0.0003 s-1, KM = 47 ± 3 μM.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Identification of stable PLP-pyruvic acid (PLP-PA) adduct in SAcBesB purified from Rhodococcus.

a) Example of the orange crystals of SAcBesB. b) UV-Vis spectrum of a SAcBesB crystal, with an extended absorbance at ~ 460 nm, indicating the bound PLP-adduct also persists throughout crystallographic experiments; however, we note the spectra for this sample was not of high quality. c) Examples of possible PLP-adducts which could be bound in the crystals. d) HPLC trace of PLP released from SAcBesB by treatment with KOH. PLP and PLP-PA are chemical standards, and the PLP-PA standard includes residual PLP from the synthesis. e) LC-MS analysis of the PLP released from SAcBesB. Traces depict the extracted ion chromatograms at m/z 318, which correspond to the PLP-PA adduct. High-resolution mass spectrometry was also used to verify the chemical formula of this compound as C11H13NO8P ([M + H]+ observed: 318.0377, [M + H]+ expected: 318.0379). f) Refinement of PLP-PA adduct in the electron density present. Left shows the clear separation between the catalytic lysine and the electron density present. Middle panel shows PLP-PA fit to the electron density present. Right panel shows the density after refinement. 2Fo-Fc electron density is shown in blue, contoured at 1.0 σ. Fo-Fc electron density is shown in green and red, and contoured at 3.0 σ and -3.0 σ respectively. PLP-PA adduct created used Phenix eLBOW. g) Abbreviated chemical mechanism for formation of the PLP-PA adduct from 2-aminoacrylate.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Sequence logos for BesB a) and other members of PF01053b).

Residues shown in both sets of sequence logos are the residues shown in stick form in Fig. 2e-f. The left set of logos shows the conserved Tyr and Arg involved in binding the phosphate of PLP. The right logo demonstrates the conservation of phenylalanine in BesB, and the YGG sequence which is most common amongst other PF01053 enzymes, as well as the conservation of other PLP-binding residues between the two enzymes. Sequence logos created using WebLogo 374.

Extended Data Fig. 6 SCaBesB-catalyzed halogen exchange.

Halogen exchange results for a) 4-iodo-allylglycine and b) 4-fluoro-allylglycine, with 1 and 2 as substrates in HEPES buffer (pH 7.5).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Reversibility of the reverse reaction as demonstrated by solvent exchange in D2O with SSpBesB.

a) All four non-acidic protons of 3 exchanged with D2O solvent when SSpBesB is present (Ammonium Bicarbonate Buffer, pH = 7.8). b) The masses detected by LC/MS-QTOF for each exchange of 3 in D2O.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Orientation of the allenylamine (10) in WT enzyme and F231Y variant.

a) MD simulations show that the presence of Tyr231 induces a reorientation of the allene moiety in the active site of F231Y variant. The ∠(C1 – C2 – N1 – C3) dihedral angle measured along independent MD trajectories (3 replicas of 500 ns for each for both the WT and F231Y variant) describes the reorientation of the allene moiety in BesB active site. In the right panel, the representation of the normalized kernel density plot of the monitored dihedral angle along the MD simulations for allenylamine (10) (see the left figure) for WT enzyme (depicted in gray) and F231Y variant (depicted in blue) are shown. b) Representative snapshot corresponding to the most populated clusters extracted from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations describing the interactions between allenylimine (10), Arg61, Asp233 and Phe/Tyr231. As shown in the figure, the interaction between Asp233, Arg61 and PLP-phosphate is maintained in both the WT enzyme and F231Y variant. However, repositioning of the allene moiety with respect to Arg61 in F231Y prevents the deprotonation by PLP-phosphate group. The introduction of Tyr231 affects the geometric stability of the different species in the BesB active site and the orientation of the alkene/allene moiety with respect to possible deprotonation groups. While along MD simulation of ketimine (8) Tyr231 shows a similar conformation that the one adopted for Phe231 in the WT enzyme, along the simulations with intermediate-9 and allenylamine (10), residue Tyr231 samples different orientations and interacts directly with the PLP-phosphate group or other residues found in the active site (Asp233 and Asp305). This interaction causes a rearrangement of the species in the active site, as well as affects the stability of the different species. For the F231Y variant, the analysis suggests that the two deprotonation sources -Asp233 and the PLP-phosphate group- (that showed low deprotonation barriers in DFT calculations, see Supplementary Fig. 29) are not close to the Hd of the intermediates for an efficient deprotonation (see Supplementary Figs. 45, 46). These results may explain why the tyrosine at position 231 contributes to trap the allenic intermediate. See additional details in Supplementary Fig. 48.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Tables 1–5, Figs. 1–50 and references.

Supplementary Data 1

Cartesian coordinates.

Source data

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

The uncropped gel of purified BesB at different concentrations. The rightmost lanes show the gel presented in Extended Data Fig. 2b.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hedges, J.B., Marchand, J.A., Calvó-Tusell, C. et al. Terminal alkyne formation by a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme. Nat Chem Biol 22, 77–86 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01954-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01954-9