Abstract

Recent studies show that aneuploidy and driver gene mutations precede cancer diagnosis by many years1,2,3,4. We assess whether these genomic signals can be used for early detection and pre-emptive cancer treatment using the neoplastic precursor lesion Barrett’s esophagus as an exemplar5. Shallow whole-genome sequencing of 777 biopsies, sampled from 88 patients in Barrett’s esophagus surveillance over a period of up to 15 years, shows that genomic signals can distinguish progressive from stable disease even 10 years before histopathological transformation. These findings are validated on two independent cohorts of 76 and 248 patients. These methods are low-cost and applicable to standard clinical biopsy samples. Compared with current management guidelines based on histopathology and clinical presentation, genomic classification enables earlier treatment for high-risk patients as well as reduction of unnecessary treatment and monitoring for patients who are unlikely to develop cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Early diagnosis of cancer is one of the best strategies to improve patient survival and decrease treatment-related side effects that contribute to poorer health; however, this strategy poses a risk of overtreatment6. Therefore, accurate biomarkers of early cancer progression are needed to stratify patients. Copy number (CN) alterations, although common in cancer, are rarely found in normal tissues, raising the question of whether these signals could help diagnose patients earlier.

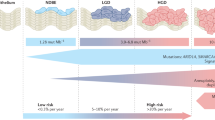

This strategy can be tested in esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), which has a 5-year survival rate of less than 20%7. Its precursor tissue is known as Barrett’s esophagus (BE); however, the risk for a patient with BE progressing to EAC is only around 0.3% per annum8. Current surveillance programs focus on the presence and grade of dysplasia in BE patients as determined by histopathological examination of biopsies. Low- (LGD) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD) are used as surrogates for early cancer transformation and trigger intervention, commonly by endoscopic resection and radiofrequency ablation (RFA)9,10. Additional risk factors for progression include increasing age, male gender, greater length of the BE segment and tobacco use at the initial evaluation, although these are not yet part of the clinical guidelines11.

Improvements in risk assessment have focused on identifying individual molecular biomarkers, particularly p53 expression12,13,14,15,16 and DNA-methylation changes17,18. However, identification of mutational biomarkers for progression has been difficult, due to the low frequency of recurrent point mutations in either BE19 or EAC20,21. Instead, EAC and BE are characterized by early and frequent genomic (CN and structural) instability20,21,22,23,24. As ongoing genomic instability leads, to a large extent, to clonal diversity, multiple investigations have focused on the heterogeneity and diversity of BE tissues25 as markers of higher risk26,27,28,29.

We investigated genome-wide CN instability as a marker for risk of progression using shallow whole-genome sequencing (sWGS; average depth 0.4×) in a retrospective, demographically matched, case–control cohort of patients (n = 88), with all available endoscopy samples (n = 777) collected during clinical surveillance for BE (Fig. 1a). Shallow WGS was chosen as the protocol because it provides a genome-wide perspective on CNs and the level of genomic instability and has been optimized for use in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples30.

a, The case–control cohort design for the discovery patient cohort (n = 88). Nonprogressor (NP) patients had a minimum follow-up of 3 years; progressor (P) patients had a minimum 1-year follow-up; all patients start at nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE). Archival samples were collected from every available endoscopy over time, and along the length of the BE segment. b–d, Bar plots showing the adjusted CN values across the genome in 5-Mb windows, with relative (within each sample) gains shown in the positive y axis, and relative losses shown in the negative y axis. b, Genomic CN profiles of individual samples for an NP patient (top) and a P patient (bottom). The colors across the chromosomes in each sample are based on the location relative to the place it was taken in the esophagus (sample nearest to the esophageal–gastric junction at the bottom, up the BE segment), and the ideograms to the right of the plots show the samples that belong to a single endoscopy indicated by the year. Note the variability in the CN profiles within samples from the progressor patient in chromosomes 14 and 17, in contrast to the shared pattern across the NP patient in those regions. c,d, Distribution of relative CN values at each genomic segment across all samples in the NP and P patient groups. The gray in the middle is the median ± 1 s.d., indicating a probable diploid genome value. Purple and green show the range of relative gains and losses, respectively. In c all samples, regardless of pathology, are plotted and a large variation in the CN between P (n = 349) and NP (n = 424) patients is clear (that is, chromosomes 1, 4, 9 and 11). In d only NDBE samples from NP (n = 346) and P (n = 172) patient groups are plotted, and the P patients still show a much larger CN signal despite being pathologically indistinguishable.

CN patterns were examined at multiple levels of the esophagus to understand how patients who progress differ from nonprogressors. We observed that the genomes of individual progressive patients display a generalized disorder across the genomes that varies between samples and over time (Fig. 1b). In addition, CN changes were not confined to cytological atypia (for example, LGD, HGD), because similar profiles were observed for the nondysplastic BE (NDBE) samples (n = 518; Fig. 1c,d).

The CN information and a measure of overall complexity (see Methods and also Extended Data Fig. 1) were used to generate a crossvalidated, elastic-net-regularized logistic regression model of progression and classification, with the endpoint HGD or intramucosal cancer (IMC; see Methods), and subsequently validated using an independent cohort of 76 patients (n = 213 samples), alongside an orthogonal validation of the Seattle BE Study SNP array samples (n = 1,272) from 248 patients31.

This model was designed to be independent of demographic risk factors11 because our cohort was matched for sex, BE segment length, age at diagnosis and smoking status (see Supplementary Table 1). We used the area under curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) to evaluate the model training performance. As the model included the diagnostic samples with the most extreme CN (for example, HGD and IMC), we additionally trained a model excluding these, and found that the AUC concordance was high (see Extended Data Fig. 2a), indicating that the model was not sensitive to extreme samples. Aggregating predictions either per endoscopy (mean or maximum sample predictions) or per patient (mean or maximum predictions excluding HGD/IMC samples) did not measurably increase the prognostic accuracy (see Extended Data Fig. 2b), suggesting that a single sample (for example, pooled four-quadrant biopsy) may be sufficient for prediction, which could be ideal for clinical application.

Using all sample predictions generated by the model we evaluated the relative risk (RR) across the cohort. Those samples with the highest RR were more than 20× more likely to progress than average, whereas those with the lowest RR were 10× less likely (Fig. 2a). This information enabled us to calibrate risk classifications based on the enrichment of samples from progressor or nonprogressor patients to maximize the sensitivity of our classes: ‘low’ (probability (Pr) ≤ 0.3; sensitivity = 0.87, specificity = 0.65), ‘moderate’ (0.3 > Pr < 0.5) or ‘high’ (Pr ≥ 0.5, sensitivity = 0.72, specificity = 0.82).

a, Histogram of the log(RR) (x axis) of cancer progression across all samples (n = 773) in the discovery cohort, based on the leave-one-patient-out predictions (number of samples, y axis). The samples with the highest RR are predicted to have >30× greater risk of progression (red), whereas the samples with the lowest RR are predicted at a 10× lower risk (blue). The inset shows the calibration of the predicted (x axis, ratio of progressor:nonprogressor (P:NP) patient samples) and mean observed probability (y axis) of progression, evaluated in deciles. The ‘low’ (blue) and ‘high’ (red) risks are enriched for nonprogressor and progressor patients, respectively. Error bars show the 95% confidence interval of the observed:predicted ratio of patients in each decile. b,c, Rate of sample risk classifications in the discovery cohort of 88 patients (n = 773 samples) (b) plotted per pathology (for example, NDBE, ID, LGD, HGD, IMC). The blue bar in ID is 3.1%, and the blue and yellow bars in HGD are each 2.7%. These show that our model can predict progression before pathological changes are visible in NDBE samples and that these predictions are consistent in the independent validation cohort of 76 patients (n = 213 samples) (c). d, Illustration of risk classes across all samples in the discovery cohort (n = 773). The row above the line shows nonprogressor patients (n = 43), whereas the row below the line shows progressor patients (n = 45). Each box of tiles denotes samples from a single patient, indicated by the study-allocated patient number above each box. On the x axis endoscopies are plotted from the baseline on the left, to the endpoint (HGD/IMC in progressors, last available for nonprogressors) endoscopy on the right. The y axis indicates the relative location of the sample, starting from the sample nearest the esophageal–gastric junction (EGJ) at the bottom up the length of the BE segment. Pop-out: heatmap for patient 69 zoomed in to show the axis labels. Absolute time and location will be different in each patient. All heatmaps showing axis labels and pathology are included in Extended Data Fig. 5.

Samples from patients who progressed were classified as ‘high risk’ for progression independent of histopathology (Fig. 2b). Most importantly, CN profiles in NDBE samples that belonged to progressor patients were classified as high risk in 60.5% (104/172), whereas in nonprogressor patients 64.7% (224/346) of samples were classified as ‘low risk’.

The model was then used to predict and classify risks per sample for the validation cohort (76 patients, 213 samples). Of samples from nonprogressor patients, 78/142 (55%) were classified as low risk, and 55/71 (77%) of samples from patients who progressed were classified as high risk. As in the discovery cohort, high-risk classification of progressor patient samples was largely independent of histopathology (Fig. 2c). Similarly, when we used our model to classify the historical Seattle study patient dataset (n = 248, samples = 1,272 SNP array) we again find that samples from progressors are classified as high risk regardless of pathology (see Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4). However, in this case the algorithm unsurprisingly suffers a loss of accuracy due to the differences in the methodology (see Supplementary Information for complete analysis and endpoint differences).

When sample classifications were plotted according to their spatial distribution in the segment and time of collection in the clinical history, strikingly concordant patterns emerged. Most progressive patient samples are classed as high risk throughout the disease history, whereas nonprogressive patient samples are consistently low risk (Fig. 2d and see also Extended Data Fig. 5). This concordance is evident when we plot the highest risk at each time point per patient (Fig. 3a). For patients who progress, 50% (8/16) of endoscopies had at least one sample classified as high risk ≥8 years before transformation. This classification is in accordance with current diagnostic guidelines that require only a single dysplastic sample to recommend treatment for a patient (Fig. 3b). Cases who lack early CN patterns of progression acquired these over the following years, leading to 78% (18/23) of endoscopies with at least one high-risk sample 1–2 years before HGD/IMC diagnosis.

a, Per-endoscopy, mean aggregated risks plotted per patient (y axis) over time (x axis) in the months since the initial endoscopy (time 0). The lines between each time point are colored by the maximum (between the initial and final endoscopy) risk classification. The right plot shows patients who progressed, with most patient endoscopies consistently classified as ‘high’ risk. Similarly, in the left plot showing nonprogressor patients, there is a group consistently predicted as ‘low’ risk. The interesting patients are the nonprogressors who have consistently been ‘high’ risk. Follow-up continues on these patients and it is possible that they may ultimately progress to HGD/IMC. b, The progressive patients, using the highest risk (similar to the current guidelines using the highest pathology grade), show that CN can identify 50% of high-risk endoscopies in patients >8 years before HGD or cancer. Bars are the ratio of ‘high’-risk endoscopies to all endoscopies for that time period; error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

More interesting were the patients who have not yet progressed but display a consistent pattern of high-risk endoscopies. Two patients were high risk in every sequenced sample, whereas the remaining patients displayed a mix of risks at each time point (Fig. 2d), presenting what could be clonal diversity in very early progression to EAC (follow-up for these patients continues) and resulting in consistent high risk over time (Fig. 3a).

Statistical algorithms can be improved by increasing the size of the dataset. We therefore conducted subsampling of the discovery cohort with increasing numbers of patients and model training as described in Methods. With each increment in the number of patients the predictive accuracy of the model increased, reaching a (crossvalidated) AUC of 0.89 (specificity = 0.83, sensitivity = 0.82) when combining all discovery and validation patients (n = 164; see Extended Data Fig. 6), indicating that a larger knowledge bank of CN and progression data from BE will continue to improve the precision of patient stratification and the sensitivity of the model, by adding stronger statistical signals and accounting for broader biological variation.

Current guidelines for the management of BE focus on the length of the BE segment and the presence or absence of LGD/HGD in any biopsy sample taken during endoscopy32,33. Most of our patients were under treatment before the current treatment recommendations for LGD, and hence we can compare a set of recommendations based on the current guidelines33 with our model applying similar criteria, but overlaying our risk classifications (Fig. 4a). We applied these recommendations across our entire discovery cohort (88 patients) and evaluated the first 2 endoscopies available excluding the endpoint (Fig. 4b and see also Supplementary Table 2). Using these criteria at the patient’s second surveillance endoscopy available (that is, several years before transformation), 54% of progressor patients (19/35) would have received earlier treatment. Only five of these patients had repeat LGD diagnoses that could recommend earlier treatment or more aggressive surveillance under current pathology-based guidelines. Of progressor patients, 40% (14/35) would continue to receive yearly surveillance per current guidelines. The remaining 6% (2/35) would have been recommended reduced surveillance (3–5 years), but they would not have been diagnosed any differently under current guidelines because they were consistently NDBE. One patient (13) may have had delayed treatment, but this would have occurred under current guidelines as well because no dysplasia was identified before transformation. Of patients who have not progressed, 51% (21/40) would have less frequent endoscopies, 33% (13/40) would continue to receive yearly surveillance per current guidelines and 17% (7/40) would have had potentially unnecessary treatment compared with current guidelines. Three patients from our discovery cohort are shown with the guidelines compared (Fig. 4c,d) as examples. Furthermore, the increasing sensitivity of the model as samples are taken closer to the endpoint is evident, because the most progressive patients are recommended treatment at their penultimate endoscopy whereas none would be recommended longer surveillance times.

a, A schematic overview of surveillance guidelines based on the CN model risk classes. It is important to note that these guidelines would apply at each endoscopy, and that they use information from the previous endoscopy to determine the treatment or surveillance. b, This schematic used to characterize the discovery cohort patients after their second endoscopy (many years before dysplastic transformation); patients with only a single sequenced endoscopy before their endpoint are excluded for a total n = 76 patients (see Supplementary Table 2). The y axis provides the four recommendations in order from the schematic in a. All bars show the total number of patients for the specific recommendation split between nonprogressor (blue) and progressor (red) patients. In ‘3- to 5-year surveillance’ at the top, the blue bar indicates the number of nonprogressor patients who would have reduced treatment needs over time (n = 21), whereas, in the ‘RFA’ recommendation at the bottom, the red bar shows those progressor patients who would have had earlier intervention (n = 19). All patients in the middle two groups would receive the same surveillance as current guidelines recommend. c–e, Individual patients with each sample plotted at the time of endoscopy and location within the esophagus. Samples are colored based on their risk class, and shapes inside the tiles describe diagnosed histopathology of the sample. Relevant clinical information is included above each endoscopy plot, including the length of the BE segment and patient age at diagnosis. British Society of Gastroenterology’s (BSG) recommendations for each patient are based on the 2014 BE management guidelines33 and shown in gray text; the blue text indicates CN model recommendations from the schematic in a. EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Below the patients are the overall follow-up recommendations for the current guidelines and the CN model.

Recent evidence from the large-scale pan-cancer studies have suggested that genomic alterations are present many years before detectable disease1 in many cancer types. BE constitutes a known pre-malignant condition with historical follow-up to test whether genomic medicine can contribute to early cancer detection. Previous studies of BE progression have shown that genomic and epigenetic changes are present before cancer progression and differ in patients who do ultimately develop cancer including: p53 expression12,14, DNA-methylation changes17,18, CN losses and copy neutral loss of heterozygosity26,28,34, and high clonal diversity27.

However, our analysis has shown that even highly variable CN profiles generated from the entire biopsy sample (not dissected or separated) translate into surprisingly stable predictions of a patient’s risk of progression. Furthermore, these single-sample predictions were as accurate as aggregated data from multiple biopsies across the entire endoscopy or patient, showing that, despite high levels of divergence, there are common patterns of CN alterations indicative of progressive disease. This level of predictive power using a genome-wide algorithm is more challenging to achieve with a focused biomarker approach given the disease heterogeneity.

Perhaps most interestingly for biomarker investigations is that, although our statistical model selects some genomic regions of instability as features that are known to be early drivers of EAC (for example, TP53; see Extended Data Fig. 7), few other features have any clearly associated tumor-suppressor genes or other cancer-related activity (see Supplementary Table 3). The heterogeneous nature of BE would partly explain the differences between the features our model selects as contributing to progression from those found in previous studies28; however, there is currently no clear functional explanation for most of the features identified. It is likely that the sum of many small changes and the breakdown of gene-regulatory control fuel oncogenicity.

Although the present study provides good evidence that genomic changes can predict future cancer risk, it is limited by the relatively small number of patients in the cohort, particularly patients who progress. Future studies that include more longitudinal genomic data will improve the sensitivity and specificity estimates of this model.

Ultimately, the combined use of low-cost genomic technologies, standard clinical samples and statistical modeling presented here is an example of how genomic medicine can be implemented for early detection of cancer. This demonstrates that genomic risk stratification has a realistic potential to enable earlier intervention for high-risk conditions, and at the same time reduce the intensity of monitoring and even reduce overtreatment in cases of stable disease.

Methods

Patient cohorts

A nested case–control cohort of 90 patients was initially recruited to the present study from patients who had been under surveillance for BE in the east of England from 2001 to 2016 for a total of 632 person-years. Permission to analyze existing clinical diagnostic samples was approved by the North West Preston Research Ethics Committee (REC 14-NW-0252). Cases comprised 45 patients who progressed from NDBE to HGD or IMC with a minimum follow-up of 1 year (mean ± s.d. = 4.6 ± 3.7 years). Controls were 45 patients who had not progressed beyond LGD, starting from NDBE with a minimum follow-up of 3 years (6.7 ± 3.2 years). Cases and controls were matched for age, gender and length of BE segment (see Supplementary Table 1). Patients had endoscopies at intervals determined by clinical guidelines with four-quadrant biopsies taken every 2 cm of BE length (the Seattle protocol). One nonprogressor patient revoked consent before analysis and a second nonprogressor was later removed during analysis when multiple comorbidities affecting the esophagus were identified. A total of 777 samples were sequenced, with 773 passing our post-processing quality control. An additional 8 technical replicates from 2 patients were sequenced for comparison, but only one set of replicates was included in the 773-sample set.

An independent, unmatched cohort of 75 patients was subsequently selected from patients under surveillance for BE in the east of England from 2001 to 2018 for model validation. This cohort comprised 18 patients who had progressed from NDBE to HGD or IMC with a minimum follow-up of 1 year (6.1 ± 3.4 years) and 58 patients who had not progressed beyond LGD starting from NDBE, with a minimum follow-up of 1.5 years (5.4 ± 3.0 years). The earliest available endoscopy samples subsequent to initial BE diagnosis were obtained to assess future risk. No diagnostic endpoint samples (for example, HGD or IMC) were included. This cohort was selected from available samples with no attempt to match demographics; however, no significant differences were found between the groups (see Supplementary Table 4). A total of 219 samples was sequenced from this cohort, with 213 passing our post-processing quality control.

Each sample from both cohorts was graded by multiple expert gastrointestinal histopathologists using current clinical guidelines for IMC, HGD, LGD, indeterminate (ID) and NDBE. A single biopsy graded as HGD or IMC was considered the endpoint for progression because patients were immediately recommended for treatment in the clinic. Since 2014, patients with LGD are also routinely treated with RFA, making prospective analysis of the real rate of progression difficult.

All patients had previously given informed consent to be part of the following studies: the Progressor study (REC 10/H0305/52, Cambridge South Research Ethics Committee), Barrett’s Biomarker Study (REC 01/149, Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee), OCCAMS (REC 07/H0305/52 and 10/H0305/1, Cambridge South Research Ethics Committee), BEST (REC 06/Q0108/272, Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee), BEST2 (REC 10/H0308/71, Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee), Barrett’s Gene Study (REC 02/2/57, the London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee), Time & TIME 2 (REC 09/H0308/118, Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee), the NOSE study (REC 08/H0308/272, Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee) and the Sponge study (REC 03/306, Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee).

All patient and sample metadata were collected by study nurses at NHS Addenbrooke’s Hospital, UK and collated in Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheets.

Patient samples from the Seattle Barrett’s Esophagus Study31, which uses SNP arrays as an orthogonal measure of CN with an endpoint of EAC, were also included for further validation (see Supplementary Information).

Tissue sample processing and p53 immunohistochemistry

FFPE tissue samples from routine surveillance endoscopies were processed from scrolls, without microdissection because this protocol aims to be clinically relevant. Following the Seattle protocol for endoscopic surveillance, four-quadrant biopsies were taken every 1–2 cm of the BE length at each endoscopy per patient. At each 1- to 2-cm length the quadrant biopsies were pooled for sequencing as a single sample to ensure that sufficient DNA (75 ng) was present.

An additional section at each level of the Barrett’s segment (n = 88, n = 590 sections) was stained (immunohistochemistry) using a monoclonal antibody for wild-type and mutant p53 (NCL-L-p53-D07, ready-use solution, protein concentration 10 mg ml−1) at the NHS Addenbrooke’s Hospital, UK on the Leica BOND-MAX system using Bond Polymer Refine Detection reagents (Leica Microsystems UK Ltd.), and graded by an expert pathologist as aberrant (absent or overexpressed) or normal35,36.

Shallow WGS pipeline

Single-end 50-bp sequencing was performed at a depth of 0.4× on the Illumina HiSeq platform. Sequence alignment was performed using BWA37 v.0.7.15, and pre-processing of the reads for mappability, GC content and filtering was performed with quantitative DNA-sequencing (QDNAseq)30 using 50-kb bins. Only autosomal sequences are retained after filtering due to low-depth mappability and GC correction. Samples were segmented for CN analysis using the piecewise constant fit function in the R Bioconductor ‘copynumber‘ v.1.16 package38. Input to this function was the GC-adjusted read counts from QDNAseq.

Post-processing quality control

Per-segment residuals were calculated and the overall variance across the median absolute deviation of the segment residuals was derived as a per-sample quality control measure. This measure was developed using an additional set of samples (n = 233), from fresh–frozen tumor tissue, FFPE cell-line tissue and FFPE patient samples. No relationship was found between sample age and data quality, and post-segmentation quality issues were not resolvable (see Extended Data Fig. 8). Therefore, samples with a mean variance of the segment residuals >0.008 were excluded from analysis. This excluded more than 73% (171/233) from the quality control samples across all sample types (FFPE patient, FFPE cell line, fresh–frozen tumor). In the discovery cohort we excluded 0.5% (4/777) of samples and in the validation cohort 2% (6/219) of samples.

Statistical methods

We encoded all CN data on a genome-wide scale by taking a per-sample weighted average across the segmented values per 5-Mb window, and mean standardizing per genomic window across the entire cohort. To evaluate chromosomal instability on a larger scale, we averaged the segmented values across chromosome arms and adjusted each 5-Mb window by the difference between the window and the arm. The resulting data were 589 5-Mb windows and 44 chromosome arms. We additionally included a measure of genomic complexity (cx) by summing, per sample, the 5-Mb windows that had CN values 2 s.d. from the mean.

We performed elastic-net regression with the R glmnet39 package to fit regression models with varying regularization parameters. Fivefold crossvalidation, repeated 10×, was performed on a per-patient basis, removing all samples from 20% of patients in each fold. This process was performed in three conditions: using all samples; excluding HGD/IMC samples; and excluding LGD/HGD/IMC. The two exclusion conditions were performed to assess the contribution of dysplasia to the classification rate of the model.

The model was additionally tuned on two parameters: (1) QDNAseq bin size and (2) elastic-net regression penalty, between 0 (ridge) and 1 (lasso). We assessed the crossvalidation classification performance of the model at multiple QDNAseq bin sizes and multiple regression penalties. We selected the final QDNAseq bin size by comparing the leave-one-patient-out predictions from the discovery cohort with the model predictions for the validation. This was done to minimize the batch errors in the raw data (see Extended Data Figs. 9 and 10). For the regression penalty parameter, all models had a crossvalidation classification rate of 72–75%. We therefore selected the parameter that limited the number of non-zero coefficients (n = 74) and was not full lasso (for example, 0.9). Coefficients determining the log(RR) of change stemming from a unit change were calculated for each genomic region selected.

Subsequently, a leave-one-patient-out analysis (excluding all samples of an individual) was performed to generate predictions for all samples from a single individual and estimate the overall model accuracy using the AUC of the ROC with the R pROC40 package.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Sequencing data and associated metadata that support the present study have been deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive under accession number EGAD00001006033. The code and model that support these findings have been provided as an R package in a GitHub repository (https://github.com/gerstung-lab/BarrettsProgressionRisk). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gerstung, M. et al. The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Nature 578, 122–128 (2020).

Mitchell, T. J. et al. Timing the landmark events in the evolution of clear cell renal cell cancer: TRACERx renal. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.020 (2018).

Lee, J. J.-K. et al. Tracing oncogene rearrangements in the mutational history of lung adenocarcinoma. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.013 (2019).

Abelson, S. et al. Prediction of acute myeloid leukaemia risk in healthy individuals. Nature 559, 400–404 (2018).

Gregson, E. M., Bornschein, J. & Fitzgerald, R. C. Genetic progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 115, 403–410 (2016).

Esserman, L. J. et al. Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: a prescription for change. Lancet Oncol. 15, e234–e242 (2014).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 7–30 (2016).

Masclee, G. M. C., Coloma, P. M., De Wilde, M., Kuipers, E. J. & Sturkenboom, M. C. J. M. The incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands is levelling off. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 39, 1321–1330 (2014).

Phoa, K. N. et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs endoscopic surveillance for patients with Barrett esophagus and low-grade dysplasia: a randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 311, 1209–1217 (2014).

Shaheen, N. J. et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 2277–2288 (2009).

Parasa, S. et al. Development and validation of a model to determine risk of progression of Barrett’s esophagus to neoplasia. Gastroenterology 154, 1282–1289.e2 (2018).

Younes, M. et al. p53 protein accumulation predicts malignant progression in Barrett’s metaplasia: a prospective study of 275 patients. Histopathology 71, 27–33 (2017).

Pettit, K. & Bellizzi, A. Evaluation of p53 immunohistochemistry staining patterns in Barrett esophagus with low-grade dysplasia. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 144, A382–A382 (2015).

Sikkema, M. et al. Aneuploidy and overexpression of Ki67 and p53 as markers for neoplastic progression in Barrett’s esophagus: a case–control study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 104, 2673–2680 (2009).

Keswani, R. N., Noffsinger, A., Waxman, I. & Bissonnette, M. Clinical use of p53 in Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 15, 1243–1249 (2006).

Reid, B. J. et al. Predictors of progression in Barrett’s esophagus II: baseline 17p (p53) loss of heterozygosity identifies a patient subset at increased risk for neoplastic progression. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96, 2839–2848 (2001).

Alvi, M. A. et al. DNA methylation as an adjunct to histopathology to detect prevalent, inconspicuous dysplasia and early-stage neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 878–888 (2013).

Jin, Z. et al. A multicenter, double-blinded validation study of methylation biomarkers for progression prediction in Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Res. 69, 4112–4115 (2009).

Weaver, J. M. J. et al. Ordering of mutations in preinvasive disease stages of esophageal carcinogenesis. Nat. Genet. 46, 837–843 (2014).

Secrier, M. et al. Mutational signatures in esophageal adenocarcinoma define etiologically distinct subgroups with therapeutic relevance. Nat. Genet. 48, 1131–1141 (2016).

Frankell, A. M. et al. The landscape of selection in 551 esophageal adenocarcinomas defines genomic biomarkers for the clinic. Nat. Genet. 51, 506–516 (2019).

Nones, K. et al. Genomic catastrophes frequently arise in esophageal adenocarcinoma and drive tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 5, 5224 (2014).

Blum, A. et al. RNA sequencing identifies transcriptionally-viable gene fusions in esophageal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 76, 5587–5589 (2016).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 541, 169–175 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20805 (2017).

Ross-Innes, C. S. et al. Whole-genome sequencing provides new insights into the clonal architecture of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 47, 1038–1046 (2015).

Maley, C. C. et al. Genetic clonal diversity predicts progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 38, 468–473 (2006).

Martinez, P. et al. Dynamic clonal equilibrium and predetermined cancer risk in Barrett’s oesophagus. Nat. Commun. 7, 12158 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Assessment of esophageal adenocarcinoma risk using somatic chromosome alterations in longitudinal samples in Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Prev. Res. 8, 845–856 (2015).

Martinez, P. et al. Evolution of Barrett’s esophagus through space and time at single-crypt and whole-biopsy levels. Nat. Commun. 9, 794 (2018).

Scheinin, I. et al. DNA copy number analysis of fresh and formalin-fixed specimens by whole-genome sequencing: improved correction of systematic biases and exclusion of problematic regions. Genome Res. 24, 2022–2032 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Temporal and spatial evolution of somatic chromosomal alterations: a case–cohort study of Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Prev. Res. 7, 114–127 (2014).

Shaheen, N. J., Falk, G. W., Iyer, P. G. & Gerson, L. B. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111, 30–50 (2016).

Fitzgerald, R. C. et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 63, 7–42 (2014).

Stachler, M. D. et al. Paired exome analysis of Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 47, 1047–1055 (2015).

Kaye, P. V. et al. Novel staining pattern of p53 in Barrett’s dysplasia—the absent pattern. Histopathology 57, 933–935 (2010).

Kaye, P. V. et al. Barrett’s dysplasia and the Vienna classification: reproducibility, prediction of progression and impact of consensus reporting and p53 immunohistochemistry. Histopathology 54, 699–712 (2009).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Nilsen, G. et al. Copynumber: efficient algorithms for single- and multi-track copy number segmentation. BMC Genomics 13, 591 (2012).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who donated tissue samples to this project. The laboratory of R.C.F. is funded by a Core Programme Grant from the Medical Research Council (grant RG84369). This work was also funded by a United European Gastroenterology Research Prize (RG76026). We thank the Human Research Tissue Bank, which is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, from Addenbrooke’s Hospital. Additional infrastructure support was provided from the Cancer Research UK-funded Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre. We also thank B. J. Reid, P. C. Galipeau and C. A. Sanchez from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, for their time and help in understanding their data, as well as A. Wolfgang Jung from the EMBL-EBI for advice on survival analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. developed the statistical methods, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript and supporting information, with input from E.G., R.C.F. and M.G. E.G. gathered the discovery cohort, developed the sWGS methods, generated the sWGS data and curated the clinical information with support from A.V.J. The initial processing pipeline was developed by D.C.W., D.J.W. and M.D.E., and provided input to the data analysis for the sWGS data. W.J., R.d.l.R., C.K. and A.M. identified, collected and assessed pathology for patient samples. S.A., A.B. and C.K. sequenced the validation cohort and quality control samples. R.C.F. initiated and jointly supervised the study with M.G.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.C.F. is named on patents for Cytosponge and related assays that have been licensed by the Medical Research Council to Covidien GI Solutions (now Medtronic).

Additional information

Peer review information Javier Carmona was the primary editor on this article, and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Differences in genomic complexity.

a, Per-sample variance in the genomic complexity (cx) values (y-axis) between samples from progressors (n = 424) and non-progressors (n = 349). Boundaries of the box indicate the first and third quartiles of the cx value, horizontal line indicates the median. All data points are shown. While the difference between non-progressors and progressors is significant in a two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test (p-value=2.4 × 10−6), it only provides limited prognostic signal as the b, ROC curve shows. c, The total number of genomic windows (adjusted by samples per endoscopy) that are CN altered (y-axis) in the 5MB windows and chromosome arms, split by progressor (n = 41) and non-progressor (n = 43) patients at the initial endoscopy. Boundaries of the box indicate the first and third quartiles, of per-patient CN altered counts, center line indicates the median. All data points are shown. Progressors with only a diagnostic endoscopy are excluded. 5MB windows (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value=6 × 10−8) and chromosomal arms (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value 5.54 × 10−11) both show a significant difference in the number of CN alterations identified between the two groups at the initial endoscopy. d, Comparison of chromosome arm altered CN counts (y-axis) found at the initial vs the final endoscopies in progressors and non-progressors. The magnitude of the changes is significantly different between the patient groups (p-value=7 × 10−4, two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test), demonstrating that alterations to the genomic landscape are apparent in low-resolution WGS data.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Model comparisons for best prediction accuracy.

a, Shows the comparison of the model used in the analysis presented (trained on all samples, n = 773) versus a model which excludes the most extreme histopathological samples (excluding HGD/IMC, n = 711). We compare the accuracy of the ROC AUC using the best sensitivity threshold (Pr = 0.3) presented in Fig. 2a of the main paper. A model trained without use of the extreme samples shows no decrease prediction accuracy indicating that these samples are not driving the differences in the model. b, ROC AUC values describing the prediction accuracy for models trained on different sets of data and various aggregations of per-sample predictions also using the best sensitivity threshold (Pr = 0.3). The first set of bars provides the ROC values for the reference model per-sample predictions (n = 773). The following bars describe the ROC values for aggregated predictions on the same samples: mean and max prediction per endoscopy, mean and max prediction per patient (excluding the final HGD/IMC samples). The aggregated predictions do not differ from the per-sample predictions indicating that a single sample may be sufficient for accurate prediction. All error bars denote the 95% confidence interval for the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC at a threshold of Pr = 0.3.

Extended Data Fig. 3 External validation on Seattle Barrett’s Study SNP data.

Predicting the Seattle Barrett’s Study SNP data using our sWGS CN model results in a lower AUC of 0.77 for all samples (including blood/gastric normals as non-progressor controls) a, Restricted to only BE samples (that is excluding normal), with our higher sensitivity threshold results in an AUC of 0.71 (sensitivity = 0.82, specificity=0.34) b, Overall, the progressor samples show the same pattern of risk classification that the sWGS samples did with high risk classifications occurring at a higher rate in progressive patients independent of pathology. The HGD group in the non-progressor patient group also indicates that our model would classify most of these as progressive. c, Compares ROC values for the SNP data using various additional criteria including: defining patients with HGD as progressed; excluding those with less than 1% of the genome altered (low SCA) and the whole-genome duplicated non-progressor patients (NP WGD); only within the baseline (T1) and penultimate endoscopy (T2) groups respectively. Demonstrating that the model improves as the samples are taken nearer to EAC diagnosis. All error bars denote the 95% confidence interval for the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC at a threshold of Pr = 0.3. d, Plots the mean ratio of the genome altered (y-axis) versus the computationally derived purity value (x-axis) for all timepoint-merged biopsies versus the blood/gastric normal samples. None of the normal samples have more than 1% of the genome altered, and all are >90% purity. Given the issues with assessing very pure, mostly diploid samples, those samples in blue are excluded from the ROC analyses as indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Model trained on only SNP data.

a, Cross-validation classification accuracy at each elastic-net penalty value (penalty = 0 had no non-zero coefficients) for the merged (see Supplementary Information Methods) samples (n = 490) the light blue bar is the penalty value used in the sWGS model and is used for comparison. The numbers on the bars indicate the number of coefficients selected under the given penalty, coefficients in parentheses are those that are stable across 75% of the folds. Error bars show the mean classification accuracy ± s.e.m. a, Volcano plot for the (CVRR) value versus coefficient value for the 27 coefficients from the SNP data trained model. Compared to the coefficients from the sWGS model the (CVRR) values (for example coefficient of variation for the relative risk, see Supplementary Table 3 for definition) are much lower.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Per-patient risk heatmaps.

Samples from the discovery cohort (n = 773) for each progressor patient (n = 45) in a, plotted by the time prior to the final endoscopy (x-axis, endpoint=0) and esophageal location from the sample closest to the esophageal-gastric junction at the bottom up the length of the BE segment, or as many samples as were available for sequencing (y-axis). Each sample is colored by their risk class with shapes inset for each pathology grade. Non-progressor patients are shown in b, (n = 43). These correspond to the mini heatmaps in the main paper Fig. 2.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Increasing numbers of patients improves accuracy.

Analysis showing the potential for improvement by training the model with increasing numbers of patients (x-axis) from the discovery cohort (green and orange bars), combining the discovery and validation cohorts (dark purple bar), and combining all sWGS (discovery and validation) data with the SNP data from the Seattle BE Study (pink bars). In each model we assessed the a, cross-validation accuracy, the b, number of coefficients selected by the model, and finally the c, AUC for a leave-one-out analysis. The green bars are all increasing numbers of patients used in training a model from the discovery cohort (error bars are the mean ± s.e.m. from repeating each training 10 times with randomly selected patients), the orange bar represents the full discovery cohort, the purple bar is the combined discovery and validation (n = 164) cohorts, and the pink bars are the combined sWGS and SNP patients (n = 413).The discovery and validation (all sWGS data) displays consistent improvement in accuracy (0.57 to 0.75) and AUC (0.7 to 0.89) as the number of patients increases. Including the SNP data results in no improvement despite the increased number of patients indicating that the sWGS data alone provides more accurate prognostic information. d, Shows the classification rate per-sample across all 164 patients in the discovery and validation cohorts when we use a model trained on all samples (n = 986). An overall improvement in accuracy for both high and low risk patients is observed.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Cancer risk in relation to p53 IHC per sample.

a, Bars show the proportion of aberrant p53 IHC stained samples separated by pathology in samples from progressive patients. The purple bars indicate the percentage of aberrant samples for each pathology. b, The CN plot from the main paper Fig. 2c zoomed in to chromosome 17 with additional bars shown for the arm-level gains (purple) or losses (green). The blue/yellow outline boxes show the genomic regions that are predictive features of the model. The blue box indicates a loss of 17p arm, while the yellow indicates gain of the 17q arm. Tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes are indicated at their chromosomal location at the bottom of each plot.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Exemplar raw data plots for quality control.

Raw data (red dots) after QDNAseq processing and pcf segmentation (green rectangles), y-axis is the relative GC-adjusted CN value and the x-axis is chromosomal position. The mean absolute deviation (MAD) of the observed (red) versus expected (green) segments was calculated and the variance across the entire sample used to develop a quality cutoff. a, Shows a post-segmentation plot from a cell-line pellet processed into an FFPE block. The wide variance of the raw (red) points results in scattered segmentation (green) high sample mean(MAD) value of 0.015. b, Shows the raw segmented plot from a fresh-frozen EAC tumor. Clear CN alterations can be observed (that is chromosomes 8 and 13). c, Contrasts two different raw data plots from the same FFPE sample in the discovery cohort sequenced as a technical replicate. The sample comes from a non-progressor patient and may have small CN changes that are clearly shared between the two.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Parameter tuning the model.

a, Shows the cross-validation classification accuracy for each bin size (15 kb, 50 kb, 100 kb, 500 kb) at each elastic-net penalty value. Error bars are mean ± s.e.m. of the classification accuracy for each alpha value and bin size. The classification accuracy shows a consistent decline for each bin size. b, Compares the AUC, true positive and false positive rate (TPR, FPR), for each bin size using leave-one-patient-out predictions for the discovery cohort at an elastic-net regression penalty of 0.9. Again, bin size 15 kb shows the best AUC at 0.88, however 50 kb is highly concordant at 0.87. Error bars are the 95% confidence interval. c, Shows the AUC comparison at each bin size for the leave-one-patient-out discovery cohort predictions versus the validation cohort model predictions. At 50 kb the AUCs are 0.87 and 0.84 respectively while all other bin sizes show a much greater difference between the cohorts. Error bars are the 95% confidence interval.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Discretizing risks.

Rate of sample classification by probability discretization per bin size for the a, discovery cohort (n = 773 samples, 88 patients) leave-one-patient-out predictions b, and validation (n = 213 samples, 76 patients) predictions. These confirm that 50 kb is the best parameter to balance classification for type I and type II errors.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Note, Methods and Results and Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source file (b) and all processed copy number data (c–d).

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source file.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source file.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Labeled QDNA-seq output for each sample in a–c.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source file.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Killcoyne, S., Gregson, E., Wedge, D.C. et al. Genomic copy number predicts esophageal cancer years before transformation. Nat Med 26, 1726–1732 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1033-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1033-y

This article is cited by

-

The biology and therapeutic implications of heterogeneity in Barrett oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2026)

-

HPGD induces ferroptosis and autophagy to suppress esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through the LXA4–ERK1/2–U2AF2–TFRC axis

Molecular Cancer (2025)

-

Multimodal cell-free DNA whole-genome TAPS is sensitive and reveals specific cancer signals

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Engineering and biofabrication of early cancer models

Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2025)

-

Clonal cell states link gastroesophageal junction tissues with metaplasia and cancer

Nature Communications (2025)