Abstract

Previously published results demonstrated that the randomized phase 3 IMpassion031 trial met its primary objective: adding atezolizumab to neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved pathologic complete response (pCR) rate in patients with stage II/III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Here we report the prespecified final analysis of the secondary endpoints with 3 years’ follow-up, together with exploratory analyses of circulating tumor (ct)DNA. Patients with previously untreated stage II/III TNBC enrolled in 75 academic and community sites in 13 countries were randomized 1:1 to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy with either peri-operative atezolizumab (n = 165) or preoperative placebo (n = 168). Descriptive secondary endpoints included event-free, disease-free and overall survival. Long-term outcomes favored the atezolizumab group (event-free survival hazard ratio (HR), 0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.47–1.21; disease-free survival HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.44–1.30; overall survival HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.30–1.04). Among patients without pCR, 14 of 70 (20%) atezolizumab-treated and 33 of 99 (33%) placebo-treated patients received additional adjuvant therapy, frequently capecitabine. In exploratory biomarker analyses, patients with baseline ctDNA-negative status (6%) had excellent long-term outcomes. Most patients (87%) had cleared ctDNA at surgery. ctDNA-positive status at surgery identified a subset of non-pCR patients with poorest prognosis. Long-term safety was consistent with primary results. These data show that adding atezolizumab to chemotherapy for stage II/III TNBC is associated with favorable long-term outcomes, and ctDNA dynamics provide prognostic value beyond pCR. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03197935.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

An important advance in the management of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in recent years has been the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy. In patients on first-line treatment for advanced TNBC, benefit from immune checkpoint blockade is greatest in those with tumors expressing programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)1,2,3,4. However, the benefit appears to be broader in randomized phase 3 trials of preoperative (neoadjuvant) therapy for early-stage TNBC, where the addition of immunotherapy improves the efficacy of chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 status5,6,7,8,9.

The IMpassion031 trial (NCT03197935) evaluated atezolizumab added to a standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen and continued after surgery in patients with stage II/III TNBC. At the primary analysis, the pathologic complete response (pCR) rate was improved significantly with the addition of atezolizumab to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, pCR rates were 58% with atezolizumab plus chemotherapy versus 41% with placebo plus chemotherapy, representing a 17% improvement (95% confidence interval (CI), 6–27%; 1-sided P = 0.0044, crossing the significance boundary)7. The improved pCR rate was seen consistently in the subgroup of patients with PD-L1-positive TNBC (69% with atezolizumab versus 49% with placebo) and the subgroup with PD-L1-negative TNBC (48% versus 34%, respectively). The atezolizumab-containing neoadjuvant regimen demonstrated an acceptable safety profile7, and analyses of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) indicated no additional treatment burden on patients10.

Here, we report the prespecified descriptive final analysis of event-free survival (EFS), disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), PROs and safety 3 years after enrollment of the last patient. We also report exploratory longitudinal analyses assessing the potential prognostic and predictive effects of baseline and on-treatment circulating tumor (ct)DNA levels. Emerging data have highlighted the prognostic role of ctDNA in early-stage breast cancer11. In a meta-analysis, the presence of ctDNA at baseline was associated with worse long-term outcomes, particularly if ctDNA persisted after therapy12. In addition, recent data from a trial of neoadjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer showed that ctDNA clearance soon after starting neoadjuvant therapy is associated with a favorable response and that the absence of ctDNA after neoadjuvant therapy is associated with improved long-term outcomes13. However, in both of these reports, very few patients received immunotherapy for TNBC, limiting their generalizability. The IMpassion031 dataset provided the opportunity to expand our understanding of ctDNA as a potential biomarker for individualizing immunotherapy-containing treatment for early-stage TNBC.

Results

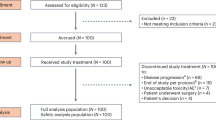

Patient disposition

Of the 455 patients screened for eligibility, 333 were randomized between 24 July 2017 and 24 September 2019; 165 were assigned to the atezolizumab group and 168 to the placebo group, representing the ITT population. All but one patient in each treatment group received neoadjuvant therapy and 308 (155 in the atezolizumab group, 153 in the placebo group) underwent surgery (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics in the two treatment groups were generally well balanced, as previously reported7 (Table 1). All patients were female.

At the final analysis (data cutoff, 28 September 2022), the median follow-up from randomization was 40.3 months in the atezolizumab group and 39.4 months in the placebo group. Among patients not experiencing a pCR at surgery (70 of 165 (42%) in the atezolizumab group versus 99 of 168 (59%) in the placebo group), a higher percentage in the placebo group received adjuvant systemic therapy (33% compared with 20% of atezolizumab-treated patients), comprising capecitabine in 26% versus 6%, respectively (Extended Data Table 1).

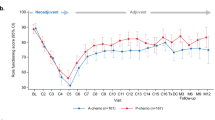

Secondary outcomes

EFS was more favorable with the atezolizumab-containing regimen (hazard ratio (HR), 0.76; 95% CI, 0.47–1.21) (Fig. 2a). The 2-year EFS rates were 85% versus 80% in the atezolizumab versus placebo groups, respectively. This direction of effect was seen irrespective of stage, PD-L1 status or regional lymph node (LN) status (Fig. 2b). Likewise, both DFS and OS favored atezolizumab, both overall (DFS HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.44–1.30; OS HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.30–1.04; Fig. 2c,d) and in the PD-L1-positive population (DFS HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.23–1.43; OS HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.26–1.91). In the neoadjuvant phase, primary tumor progression was observed in 0% versus 2.4% of the atezolizumab versus placebo groups, respectively. In the postoperative phase, distant recurrence was less common in the atezolizumab group (7.9% versus 11.3% in the placebo group), whereas local recurrence was more common (4.2% versus 1.2%, respectively) (Extended Data Table 2).

a, EFS in the ITT population. b, EFS subgroup analysis (n, number of individual patients in each subgroup; dashed line, HR in the ITT population; one patient with stage IV disease not included in subgroup analyses by stage). c, DFS in the ITT population. d, OS in the ITT population. IC, immune cells.

Final PRO analyses showed that, in both treatment groups, patients reported a gradual stabilization of their physical and role functioning and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after starting adjuvant therapy, although patients resuming atezolizumab after surgery continued to report a clinically meaningful worsening compared with baseline for role functioning (Extended Data Fig. 1). Stabilization was sustained in both treatment groups throughout the adjuvant and follow-up periods. Final analyses of the exploratory PRO endpoint of treatment side-effect bother showed no additional bother among patients receiving atezolizumab compared with chemotherapy alone, even during adjuvant therapy and through follow-up (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Safety

Safety profiles were consistent with observations at the primary analysis. The addition of atezolizumab did not compromise the ability to deliver nab-paclitaxel, doxorubicin or cyclophosphamide. There were no unexpected safety findings or treatment-related deaths with atezolizumab (Extended Data Table 3). Adjuvant atezolizumab was associated with limited additional toxicity to that already reported in the neoadjuvant phase. Most adverse events of special interest were grade 1/2, most resolved and there were no grade 5 adverse events of special interest (Extended Data Table 4).

Exploratory outcomes

Overall, 139 patients (42% of the ITT population) were evaluable for ctDNA analysis at baseline. On-treatment ctDNA samples were available from 132 patients at week 7 (during nab-paclitaxel), 133 patients at week 15 (after nab-paclitaxel, during dose-dense anthracycline therapy), 130 at surgery, 120 postsurgery and ten at recurrence (Fig. 3a).

a, Prevalence of ctDNA-positive status over time. b, ctDNA levels over time according to pCR status; shaded area, s.e. c, ctDNA levels in individual patients over time. d, Relationships between ctDNA clearance at surgery, treatment group and pCR status (n, number of individual patients in each subgroup; vertical bars, Clopper–Pearson 95% CIs). aPooled treatment groups.

Baseline characteristics in the ctDNA-evaluable population were generally representative of the ITT population (Table 1), although the ctDNA-evaluable population included more Asian patients (37% versus 26% in the ITT population). pCR rates in the ctDNA-evaluable population were 56% in the atezolizumab group versus 37% in the placebo group, similar to those in the ITT population. Clinical outcomes in the ctDNA-evaluable population (1-year DFS rates: 94% with atezolizumab versus 89% with placebo) were similar to the ITT population. Overall, longitudinal ctDNA dynamics showed that patients experiencing a pCR had greater and more durable reductions in ctDNA compared with patients not showing a pCR (Fig. 3b).

At baseline, samples from 130 of 139 patients (94%) were ctDNA-positive (Fig. 3a). The median variant allele frequency (VAF) was 1% (range, 0–30%; interquartile range, 0.13–3.25%). Patients with ctDNA-positive status at baseline were more likely to have characteristics associated with a poor prognosis (regional LN involvement, higher disease stage, larger primary tumor, higher tumor grade) than the nine patients who were ctDNA-negative (Extended Data Table 5), with the caveat of small and imbalanced sample sizes.

Absence of ctDNA at baseline was rare (nine patients (6%): four of 63 (6%) in the atezolizumab group and five of 76 (7%) in the placebo group). These patients remained ctDNA-negative at all timepoints sampled. Six had a pCR (two in the atezolizumab group versus four in the placebo group) and three did not (two versus one, respectively). Despite the absence of pCR in these three patients, only one had disease recurrence (>3 years after surgery) and none had died by the data cutoff date.

In most patients (108 of 130 (83%) with a ctDNA-positive baseline sample), ctDNA cleared (that is, changed to ctDNA-negative status) and remained undetectable throughout neoadjuvant chemotherapy (with or without atezolizumab) (Fig. 3c).

Week 7 clearance (halfway through nab-paclitaxel therapy) was assessed in the group of 123 patients who were ctDNA-positive at baseline and had a week 7 sample available for ctDNA assessment. Early (week 7) ctDNA clearance was observed in 89 of 123 patients (72%; 46 of 56 (82%) of the atezolizumab group versus 43 of 67 (56%) of the placebo group) and was associated with more favorable outcomes (Extended Data Fig. 3a). These patients tended to have lower stage (stage II in 75% versus 53% of those who remained ctDNA-positive at week 7) and no regional LN involvement (65% versus 38%, respectively). Among patients without a pCR, DFS and OS were more favorable in patients with ctDNA clearance by week 7 (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

Clearance at surgery was assessed in the group of 122 patients who were ctDNA-positive at baseline and had a sample at the time of surgery available for ctDNA assessment. Most (106 of 122 (87%)) of the patients with positive ctDNA at baseline had negative ctDNA status at the time of surgery, with no difference between treatment groups (47 of 53 (89%) of the atezolizumab group versus 59 of 69 (86%) of the placebo group) (Fig. 3d). Among patients with ctDNA clearance at surgery, pCRs were observed in 29 of 47 (62%) of the atezolizumab group versus 24 of 59 (41%) of the placebo group (Fig. 3d). Patients without ctDNA clearance at surgery tended to have higher stage (stage III in 56% versus 26% of those who were ctDNA-negative at surgery) and higher tumor grade (grade 3 in 88% versus 73%, respectively) (Extended Data Table 5). pCRs were observed exclusively in patients with negative ctDNA status at surgery (Fig. 3d). ctDNA clearance at surgery was associated with improved DFS and OS (Fig. 4a). Among patients without a pCR, the 16 with persistent ctDNA at surgery had a particularly poor prognosis compared with patients with cleared ctDNA at surgery, although the 95% CIs for the DFS HR point estimate crossed 1 (DFS HR, 2.15; 95% CI, 0.88–5.29; OS HR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.21–10.16) (Fig. 4b). Within this small subgroup, the HR point estimate favored patients treated with atezolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for DFS (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.12–3.32) and OS (HR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.04–2.68) (Extended Data Fig. 4).

Postsurgery samples were collected from 120 patients (median 23 days after surgery, range 3–62 days). Among these, samples from four patients (3%) remained ctDNA-positive after surgery (samples collected 7, 21, 29 and 42 days after surgery). All were in the placebo group, all had regional LN involvement at baseline, none had a pCR, and all experienced relapse within 1 year of surgery (Extended Data Fig. 5). All ten samples collected at the time of disease recurrence were ctDNA-positive (Fig. 3a).

Eleven patients remained ctDNA-positive from baseline through to surgery. These patients had baseline characteristics associated with a worse prognosis (64% stage III, 18% Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 1, 55% LN involvement, 45% T2/3, 73% PD-L1-negative status) and none had a pCR. Only six of these patients remained disease-free for more than 12 months. EFS, DFS and OS were all worse in persistently ctDNA-positive patients compared with patients who cleared ctDNA at any timepoint (Extended Data Fig. 3c).

Post hoc analyses

An exploratory analysis of EFS according to pCR status indicated that pCR was prognostic for long-term outcome at an individual patient level (Fig. 5). Among patients experiencing a pCR (n = 164; 58% of the atezolizumab group and 41% of the placebo group), EFS appeared to be more favorable with atezolizumab than placebo; however, no clear difference was seen in the subgroup of patients not experiencing a pCR (n = 169).

Discussion

Long-term follow-up of the randomized phase 3 IMpassion031 trial indicated that the positive impact of atezolizumab on the primary outcome measure (pCR) was supported by HR point estimates below 1 favoring atezolizumab for EFS, DFS and OS. Peri-operative atezolizumab (combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and continued as adjuvant therapy) was well tolerated and there were no unexpected safety findings. Updated PRO analyses were consistent with observations at the primary analysis10, showing a return to baseline functioning and HRQoL levels during adjuvant therapy and no additional treatment burden in patients receiving atezolizumab.

The IMpassion031 trial was neither designed nor powered for formal statistical comparison of secondary efficacy or exploratory endpoints. However, the statistically significant improvement in the pCR rate, and EFS, DFS and OS treatment effects in the same direction, are consistent with findings from the KEYNOTE-522 randomized phase 3 trial evaluating peri-operative pembrolizumab5,6,9, with the usual caveats of cross-trial comparisons. There are several important differences in trial design between IMpassion031 and KEYNOTE-522. First, the primary endpoint of IMpassion031 was pCR, whereas in the much larger KEYNOTE-522 trial, pCR and EFS were co-primary endpoints. Second, the definition of EFS differed between the two trials (disease recurrence, progression or death from any cause in IMpassion031; progression precluding definitive surgery, local or distant recurrence, second primary cancer or death in KEYNOTE-522). Third, the chemotherapy backbones differed between the two trials (nab-paclitaxel and dose-dense anthracycline-based regimen in IMpassion031; non-dose-dense anthracycline- and platinum-containing regimen in KEYNOTE-522). Fourth, and of particular relevance for survival-related endpoints, the IMpassion031 trial was unblinded after pCR assessment and patients not experiencing a pCR were allowed standard systemic adjuvant chemotherapy at the investigator’s discretion. This reflects the current standard of care in the postneoadjuvant setting based on the OS benefit from postoperative capecitabine in patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy14. More patients in the control group than in the atezolizumab group received adjuvant systemic therapy. Finally, the patient populations enrolled in the two trials were quite different, particularly with respect to LN status and PD-L1 status. Nevertheless, the consistency of results between IMpassion031 and KEYNOTE-522 (both evaluating the immunotherapy added to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and continued as adjuvant therapy), as well as effects seen in the randomized phase 2 GeparNuevo trial (evaluating the addition of durvalumab—a PD-L1 inhibitor—to neoadjuvant chemotherapy without adjuvant continuation)8,15, confirm the important role of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for early-stage TNBC.

Results from IMpassion031 contrast with findings from the open-label randomized phase 3 NeoTRIP trial16, which showed no improvement in the primary endpoint (EFS) with the addition of atezolizumab to a non-anthracycline-containing neoadjuvant regimen (without adjuvant atezolizumab continuation)17. They also contrast with the recently reported randomized phase 3 NSABP B-59/GBG 96-GeparDouze trial that did not show a significant improvement in EFS (primary endpoint) with atezolizumab given in combination with platinum-based neoadjuvant therapy and continued as adjuvant therapy18. Of note, in the NSABP B-59/GBG 96-GeparDouze trial, a numerical improvement was observed in patients with baseline characteristics associated with higher risk of recurrence (for example, node-positive disease).

In exploratory analyses of IMpassion031, pCR (ypT0/is ypN0) at an individual patient level was associated with improved long-term outcomes. In both IMpassion031 and KEYNOTE-522, patients experiencing a pCR had very good outcomes, although long-term benefit from continued immunotherapy after a pCR cannot be excluded. This observation again raises the question of treatment de-escalation in patients with a pCR—a strategy that is under investigation in ongoing trials. Outcomes in patients without a pCR were less favorable, although analyses of subgroups defined by a postbaseline variable (pCR status) should be interpreted with caution. In a prespecified exploratory analysis of 463 patients not experiencing a pCR in the KEYNOTE-522 trial, outcomes were more favorable in the pembrolizumab arm6. In contrast, post hoc exploratory analyses of IMpassion031 showed no evidence of benefit from atezolizumab in patients not experiencing a pCR. However, this cross-trial comparison is again confounded by trial design differences in the use of optimal systemic anti-cancer therapy for postoperative residual disease, which was permitted to reflect standard-of-care treatment in IMpassion031 but not in KEYNOTE-522. The imbalance in use of postneoadjuvant capecitabine, together with the small sample size and exploratory nature of these analyses, precludes any definitive conclusions on the treatment effect in patients with residual disease at surgery. Similarly, in the I-SPY2 study, which was not powered for EFS, several patients not experiencing a pCR received adjuvant systemic chemotherapy and the difference in EFS with the addition of pembrolizumab to neoadjuvant chemotherapy did not reach statistical significance19.

Exploratory longitudinal analyses from the IMpassion031 trial inform on the important prognostic effect of ctDNA both at baseline and during or following treatment in early-stage TNBC. Absence of ctDNA at baseline was rare (6% of patients), but was associated with favorable long-term outcomes, irrespective of pCR. At the other end of the spectrum, positive ctDNA status that persisted beyond surgery (observed in 3% of patients) was associated with particularly poor outcomes. In most patients, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (with or without atezolizumab) cleared ctDNA, consistent with recent findings from 38 patients treated in the Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium 030 trial20. In IMpassion031, clearance of ctDNA at week 7 was associated with more favorable outcomes, irrespective of pCR. These findings raise the question whether ctDNA clearance may act as an early surrogate of long-term outcome, potentially allowing treatment to be tailored according to the presence of ctDNA both at baseline and during on-treatment monitoring. Further investigation is required to explore this hypothesis.

Strengths of the IMpassion031 trial include the dose-dense chemotherapy backbone, the optional administration of additional systemic adjuvant therapy in patients without a pCR, and the inclusion of extensive on-treatment ctDNA sampling to allow longitudinal biomarker analysis. The peri-operative setting allowed us to use biopsy or resection tumor tissue to design a bespoke tumor-informed ctDNA assay with increased sensitivity compared with gene panel methods. We were able to show that changes in ctDNA levels during neoadjuvant treatment have prognostic value, potentially improving risk stratification for patients who do not experience a pCR. Furthermore, in contrast to many previous studies on ctDNA21,22, the analyses were performed in all patients rather than selecting only those with residual disease, and thus provide more comprehensive insight.

Study limitations include the smaller sample size required for a pCR primary endpoint and the lack of power to detect differences in EFS, DFS and OS. In addition, it is not possible to determine whether the more favorable EFS, DFS and OS are attributable to a carryover effect of atezolizumab administration in the neoadjuvant setting, continued administration in the adjuvant setting, or both. The ctDNA analysis is limited by the relatively low ctDNA levels in the postoperative setting (ctDNA detected in only 3% of patients after surgery). Furthermore, serial ctDNA evaluation in the postoperative setting was not planned in this trial but could potentially improve the sensitivity of the method for identifying patients who will subsequently experience recurrence.

Arguably, some of the exploratory findings from the IMpassion031 dataset are most insightful for future clinical practice, providing unique information on ctDNA evolution during neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without immune checkpoint blockade. The rarity of ctDNA-negative status at baseline and the associated excellent outcomes, even in the absence of a pCR, is important for patient selection for de-escalation trials. Conversely, high baseline ctDNA that persists despite treatment is associated with the worst outcomes and represents a high unmet need. A challenge for future research is to define and implement adaptive treatment strategies driven not only by tumor response but also by dynamic ctDNA monitoring23.

Methods

Patients and treatment

The trial was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) of participating institutions, including the Taipei General Hospital IRB and the Western IRB. All patients provided written informed consent. Patients were not compensated for participation.

The design of this randomized phase 3 trial has been reported in detail in the primary and PROs publications7,10. The trial enrolled women or men aged ≥18 years with untreated stage II/III TNBC (centrally assessed according to American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines) and a primary tumor >2 cm (cT2–cT4, cN0–cN3, cM0). Patients had to have an ECOG PS of 0 or 1. Patients were excluded if they had previously received systemic therapy for breast cancer or anthracycline, taxane, anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy for any malignancy; had a history of ductal or pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ within the preceding 5 years treated with surgery alone; had bilateral breast cancer; or had undergone incisional and/or excisional biopsy of the primary tumor and/or axillary LNs or axillary LN dissection before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy. Eligible patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either atezolizumab or placebo in combination with a neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen comprising 12 weeks of nab-paclitaxel followed by 8 weeks of dose-dense doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide, with filgrastim or pegfilgrastim support. Surgery was performed 2–6 weeks after the last dose of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and atezolizumab/placebo. After surgery, patients initially randomized to atezolizumab received open-label atezolizumab for an additional 11 cycles. Atezolizumab was administered intravenously at 840 mg every 2 weeks in the neoadjuvant phase (to align with the chemotherapy schedule) and at 1,200 mg every 3 weeks in the adjuvant phase (for convenience and to reduce the burden of treatment visits). Nab-paclitaxel was administered at 125 mg m−2 every week; doxorubicin 60 mg m−2 and cyclophosphamide 600 mg m−2 were administered every 2 weeks.

Uniquely, in both treatment groups, patients not experiencing a pCR at surgery were allowed to receive standard adjuvant systemic therapy at the investigator’s discretion and according to standard-of-care guidelines (with atezolizumab in patients initially assigned to atezolizumab-containing therapy). Stratification factors were disease stage (II versus III) and centrally assessed PD-L1 status (negative (immune cells (IC) < 1%) versus positive (IC ≥ 1%)) using the VENTANA SP142 immunohistochemistry assay.

Endpoints and assessments

The co-primary endpoints, previously reported, were pCR rate in the ITT and PD-L1-positive populations7. Secondary endpoints, for which the IMpassion031 trial was not powered, included EFS (time from randomization until disease recurrence, progression or death from any cause), DFS (time from surgery until disease recurrence or death from any cause in patients undergoing surgery) and OS (time from randomization until death from any cause) in the ITT and PD-L1-positive populations, and mean score/mean change from baseline score for patient-reported physical and role functioning and HRQoL. Additional PRO parameters were among the exploratory efficacy endpoints.

Patients completed the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30)24,25 and a single item (GP5, ‘I am bothered by side effects of treatment’) from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (FACT-G) instrument26 on paper at clinic visits before any healthcare interaction and before drug administration at baseline (cycle 1, day 1; starting at cycle 2 for FACT-G GP5), on day 1 of each subsequent cycle, at the end of treatment or discontinuation visit or after the last monitoring visit in the control group, and during the survival follow-up (every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for years 2 and 3 and annually thereafter). The EORTC and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) scoring manuals27,28 were used to score the PRO data along with published thresholds to identify minimally important differences within treatment groups29.

In further exploratory analyses, the prognostic and predictive effects of baseline and on-treatment ctDNA were evaluated using the tumor-informed Signatera assay (Natera). This technology has been described previously30. Plasma samples were collected at baseline (week 1), during nab-paclitaxel treatment (week 7), during anthracycline-based treatment (week 15), at surgery, at the first postsurgery clinic visit and at the time of disease recurrence. Tumor tissue and matched blood germline DNA were sequenced to identify patient-specific signatures of tumor mutations. In a subset of patients (approximately 50%), matched normal was based on whole plasma whole-exome sequencing. Subsequently, the top 16 clonal tumor mutations were selected to custom design and manufacture a personalized multiplex PCR assay for each patient, which was used to test plasma samples for the presence or absence of ctDNA. A sample was considered ctDNA-positive if at least two mutations were detected. As long-term endpoints showed similar outcomes in the two treatment arms, data from the two treatment groups were pooled for analyses of ctDNA over time to increase the sample size.

Statistical analysis

Overall, approximately 324 patients were planned to be enrolled across study stages. The statistical design and details of pCR analysis have been described in detail previously, as have EFS, DFS, OS and PROs after a median follow-up of approximately 20 months7,10. Here, we report more mature secondary endpoint results with longer follow-up. This article reports the final results of secondary and exploratory analyses with longer follow-up. pCR rates were calculated in both the all-randomized and PD-L1-positive populations. Kaplan–Meier analysis was applied to estimate median duration of EFS, DFS and OS, with the Brookmeyer–Crowley method used to construct the 95% CIs. PRO analyses were performed in the PRO-evaluable population, comprising all patients with a baseline and at least one postbaseline measurement. For the FACT-G GP5 and each item or subscale of the EORTC QLQ-C30, summary statistics (mean with 95% CIs and s.d., median and range) were calculated for absolute values and mean changes from baseline at each timepoint for each treatment group. The proportion of patients in each group responding to each response option of item GP5 by timepoint was calculated and presented graphically in bar charts.

SAS v.9.4 was used for all statistical analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All reported data are from the IMpassion031 dataset. Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient-level data through the clinical study data request platform (https://vivli.org). Further details on Roche’s criteria for eligible studies are available here: https://vivli.org/members/ourmembers. For further details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here: https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm. Biomarker data will be made available to qualified researchers at the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA) under accession number EGAS50000000974. To request access to such data, researchers can contact devsci-dac-d@gene.com or submit a data access request via the standard EGA process. The data will be released to such requesters with necessary agreements to enforce terms such as security, patient privacy, and consent of specified data use, consistent with evolving, applicable data protection laws.

References

Schmid, P. et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2108–2121 (2018).

Cortes, J. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 396, 1817–1828 (2020).

Emens, L. A. et al. First-line atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel for unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: IMpassion130 final overall survival analysis. Ann. Oncol. 32, 983–993 (2021).

Cortes, J. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 217–226 (2022).

Schmid, P. et al. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 810–821 (2020).

Schmid, P. et al. Event-free survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 556–567 (2022).

Mittendorf, E. A. et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab in combination with sequential nab-paclitaxel and anthracycline-based chemotherapy versus placebo and chemotherapy in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion031): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 396, 1090–1100 (2020).

Loibl, S. et al. A randomised phase II study investigating durvalumab in addition to an anthracycline taxane-based neoadjuvant therapy in early triple-negative breast cancer: clinical results and biomarker analysis of GeparNuevo study. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1279–1288 (2019).

Schmid, P. et al. Overall survival with pembrolizumab in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 1981–1991 (2024).

Barrios, C. H. et al. Patient-reported outcomes from a randomized trial of neoadjuvant atezolizumab-chemotherapy in early triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 8, 108 (2022).

Papakonstantinou, A. et al. Prognostic value of ctDNA detection in patients with early breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 104, 102362 (2022).

Nader-Marta, G. et al. Circulating tumor DNA for predicting recurrence in patients with operable breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ESMO Open 9, 102390 (2024).

Magbanua, M. J. M. et al. Clinical significance and biology of circulating tumor DNA in high-risk early-stage HER2-negative breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Cell 41, 1091–1102.e1094 (2023).

Masuda, N. et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 2147–2159 (2017).

Loibl, S. et al. Neoadjuvant durvalumab improves survival in early triple-negative breast cancer independent of pathological complete response. Ann. Oncol. 33, 1149–1158 (2022).

Gianni, L. et al. Pathologic complete response (pCR) to neoadjuvant treatment with or without atezolizumab in triple-negative, early high-risk and locally advanced breast cancer: NeoTRIP Michelangelo randomized study. Ann. Oncol. 33, 534–543 (2022).

Gianni, L. et al. Event-free survival (EFS) analysis of neoadjuvant taxane/carboplatin with or without atezolizumab followed by an adjuvant anthracycline regimen in high-risk triple negative breast cancer (TNBC): NeoTRIP Michelangelo randomized study. Ann. Oncol. 34, S1258 (2023).

Geyer, C. E. GS3-05: NSABP B-59/GBG-96-GeparDouze: a randomized double-blind phase III clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with atezolizumab or placebo followed by adjuvant atezolizumab or placebo in patients with stage II and III triple-negative breast cancer. Presented at: San Antonio Breast Cancer Conference; December 10–13, 2024; San Antonio, TX. GS3-05.

Nanda, R. et al. Effect of pembrolizumab plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy on pathologic complete response in women with early-stage breast cancer: an analysis of the ongoing phase 2 adaptively randomized I-SPY2 trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 676–684 (2020).

Parsons, H. A. et al. Circulating tumor DNA association with residual cancer burden after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer in TBCRC 030. Ann. Oncol. 34, 899–906 (2023).

Stecklein, S. R. et al. ctDNA and residual cancer burden are prognostic in triple-negative breast cancer patients with residual disease. NPJ Breast Cancer 9, 10 (2023).

Radovich, M. et al. Association of circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells after neoadjuvant chemotherapy with disease recurrence in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: preplanned secondary analysis of the BRE12-158 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 1410–1415 (2020).

Turner, N. C. et al. Results of the c-TRAK TN trial: a clinical trial utilising ctDNA mutation tracking to detect molecular residual disease and trigger intervention in patients with moderate- and high-risk early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 34, 200–211 (2023).

Aaronson, N. K. et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 85, 365–376 (1993).

Osoba, D. et al. Modification of the EORTC QLQC30 (version 2.0) based on content validity and reliability testing in large samples of patients with cancer: the Study Group on Quality of Life of the EORTC and the Symptom Control and Quality of Life Committees of the NCI of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Qual. Life Res. 6, 103–108 (1997).

Cella, D. F. et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 11, 570–579 (1993).

Fayers, P. et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, 2001).

Cella, D. Manual of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System. v.4 (Center on Outcomes, Research and Education (CORE), Evanston Northwestern Healthcare and Northwestern University, 1997).

Osoba, D. et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J. Clin. Oncol. 16, 139–144 (1998).

Powles, T. et al. ctDNA guiding adjuvant immunotherapy in urothelial carcinoma. Nature 595, 432–437 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and their families and the study investigators and staff at participating sites. F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd sponsored and funded the trial, provided the study drug (atezolizumab) and collaborated with academic authors on the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, preparation of the manuscript and decision to publish. The study drug nab-paclitaxel was provided through an agreement with Celgene. Medical writing assistance for this paper was provided by J. Kelly (Medi-Kelsey Ltd), funded by F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.A.M.: conceptualization, resources, investigation, methodology, supervision and writing—review and editing. Z.J.A.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, validation, visualization, software, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. N.H.: conceptualization, resources and writing—review and editing. H.Z.: conceptualization, resources and writing—review and editing. S.S.: conceptualization, resources and writing—review and editing. K.H.J.: resources and writing–review and editing. R.H.: resources and writing—review and editing. A.K.: resources and writing—review and editing. J.S.: resources and writing—review and editing. H.I.: resources and writing—review and editing. M.L.T.: resources and writing—review and editing. C.F.: resources and writing—review and editing. K.P.: resources and writing—review and editing. A.Q.: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, validation, visualization, software and writing—review and editing. M.D.: investigation, methodology, data curation and writing—review and editing. Y.X.: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, validation, software and writing—review and editing. M.L.-H.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, supervision, project administration, writing—original draft and writing–review and editing. E.S.-K.: investigation, methodology, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. L.M.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. S.Y.C.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology and writing–review and editing. C.H.B.: conceptualization, resources, investigation and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.A.M. reports compensated service on scientific advisory boards for AstraZeneca, BioNTech, Merck and Moderna; uncompensated service on steering committees for Bristol Myers Squibb and Roche/Genentech; speaker honoraria and travel support from Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD) and institutional research support from Roche/Genentech (via SU2C grant) and Gilead. E.A.M. also reports research funding from Susan Komen for the Cure for which she serves as a Scientific Advisor, and uncompensated participation as a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Board of Directors. Z.J.A., E.S.-K., L.M. and S.Y.C. are employees or former employees of Genentech and hold or held shares in Roche. N.H. reports consulting fees from Gilead, Sandoz and Seagen; speaker honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Roche and Seagen; honoraria for data safety monitoring board from Roche; and a leadership position at the West German Study Group (minority ownership). H.Z. reports honoraria for advisory/consultancy roles for Roche/Genentech. S.S. reports speaker honoraria from Chugai, Kyowa Kirin, MSD, Novartis, Eisai, Takeda, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Taiho, Ono, Nippon Kayaku, Gilead and Exact Sciences; research grants (to institution) from Taiho, Eisai, Chugai, Takeda, MSD, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Eli Lilly and Sanofi; honoraria for advisory/consultancy roles for Chugai/Roche, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Kyowa Kirin, Daiichi Sankyo and MSD; and uncompensated leadership roles for the Japan Breast Cancer Research Group, Japanese Society of Medical Oncology and Breast International Group. K.H.J. reports advisory roles for AstraZeneca, Bixink, Everest Medicine, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda Pharmaceuticals and Daiichi Sankyo. A.K. reports advisory roles for Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Amgen, Daiichi and MSD; a research grant from the German Breast Group and travel/accommodation expenses from Stada. J.S. reports research grants (to institution) from MSD, Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Pfizer, GSK, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim and Seagen. H.I. reports advisory roles for Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Lilly and Sanofi; speaker honoraria (personal) from Pfizer and Taiho and speaker honoraria (personal and to institution) from Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, MSD, Amgen, Sanofi, Lilly, Novartis, Bayer, Pfizer, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Boehringer and Nihon Kayaku. M.L.T. reports research grants (to institution) from Arvinas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Hummingbird Biosciences, Merck, Novartis, OncoSec Medical and Pfizer; and honoraria for advisory roles from AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech/Roche, Gilead (DSMC), GlaxoSmithKline, G1 Therapeutics (DSMC), Guardant, Merck, Natera, Novartis, Pfizer, RefleXion, Replicate and Sanofi. C.F. reports honoraria from Pfizer, Bayer, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Merck, Roche Canada, Knights Therapeutics and Janssen Oncology; honoraria from Merck, AstraZeneca, Novartis and Roche; speaker’s bureau for Merck, Knight Therapeutics, AstraZeneca and Novartis; expert testimony for Seattle Genetics/Astellas and research funding (to institution) from Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, Janssen Oncology, Zymeworks, Seattle Genetics and Sermonix Pharmaceuticals. K.P. reports honoraria (to institution) for advisory/consultancy roles from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche, Vifor Pharma, Eli Lilly, Pierre Fabre, McCann Health, Roularta, Teva, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer and MSD; personal honoraria for consultancy from Gilead, Novartis, MSD and Roche; personal honoraria for advisory boards from Seagen, AstraZeneca and Pfizer; speaker honoraria (to institution) from Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Mundi Pharma, MSD and Medscape; personal speaker honoraria from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Exact Sciences, Focus Patient, Pfizer and Gilead Sciences; ownership interest in Need Inc.; funding (to institution) from Sanofi and uncompensated leadership roles for the Belgian Society of Medical Oncology and EORTC Breast Cancer Task Force. A.Q., M.D. and M.L.-H. are employees of F. Hoffmann-La Roche and hold shares in Roche. Y.X. is an employee of Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and holds shares in Roche. C.H.B. reports research funding (to institution) from Nektar, Pfizer, Polyphor, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Exelixis, Regeneron, Novartis, GSK, Janssen, OBI Pharma, Lilly, Seagen, Roche, BMS, MSD, AstraZeneca, Novocure, Aveo Oncology, Takeda, PharmaMar, Gilead Sciences, Servier, Tolmar, Nanobiotix and Dizal Pharma; clinical research organization funding (to institution) from TRIO, Labcorp, ICON, IQVIA, Parexel, Nuvisan, PSI, Worldwide, Latinaba, Fortrea, PPD and Syneos Health; ownership or stocks in Tummi and MEDSir; advisory boards/presentations/consulting for Gilead, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Eisai, Bayer, MSD, AstraZeneca, Zodiac, Lilly, Sanofi and Daiichi and uncompensated leadership roles for the Breast International Group, Latin American Cooperative Oncology Group, ASCO and ESMO. R.H. declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Anna Maria Ranzoni, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Mean change from baseline over time for patient-reported outcomes.

a, Physical functioning. b, Role functioning. c, HRQoL. Error bars depict 95% CIs. BL, baseline; C, cycle; GHS, Global Health Status; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; M, month; TxDC, treatment discontinuation.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Patient-reported treatment bother, FACT-G GP5 item ‘I am bothered by side effects of treatment’.

Proportion of patients selecting each response option of the FACT-G GP5 item by visit in the atezolizumab-chemotherapy and chemotherapy-alone groups. FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General.

Extended Data Fig. 3 DFS and OS according to.

a, ctDNA cleared versus not cleared at week 7. b, ctDNA cleared versus not cleared at week 7 according to pCR status. c, ctDNA status (always positive (n = 11) versus negative for at least one timepoint (n = 119)).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Treatment outcomes in patients without pCR or ctDNA clearance.

Exploratory analysis of DFS and OS by treatment group in non-pCR patients with positive ctDNA status at surgery. Vertical bars represent censoring.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Outcomes according to post-surgery ctDNA status.

a) DFS. b) OS. Vertical bars represent censoring.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Trial protocol.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mittendorf, E.A., Assaf, Z.J., Harbeck, N. et al. Peri-operative atezolizumab in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer: final results and ctDNA analyses from the randomized phase 3 IMpassion031 trial. Nat Med 31, 2397–2404 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03725-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03725-4

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic biomarkers in hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer trials: a new hope for precision oncology

npj Breast Cancer (2026)

-

High mid-treatment tumour RNA disruption in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer is associated with improved disease-free survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Breast Cancer Research (2025)