Abstract

Current hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) conditioning strategies cause widespread tissue damage and systemic toxicities, especially in patients with DNA-repair deficiencies such as Fanconi anemia (FA). We have developed an alternative conditioning approach that incorporates the anti-CD117 antibody, briquilimab, which targets host hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in place of genotoxic irradiation- and busulfan-based chemotherapy. Here we report a phase 1b clinical trial in patients with FA and bone marrow failure, evaluating safety and efficacy of briquilimab-based conditioning in combination with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin, cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and rituximab immunosuppression and T cell receptor (TCR)αβ+ T cell-depleted and CD19+ B cell-depleted haploidentical HSCT. Primary endpoints of the trial included safety and engraftment, and secondary endpoints included pharmacokinetic measures and hematological and immunological recovery. All three patients have each undergone 2 years of follow-up to complete the phase 1b analysis. No treatment-emergent adverse events or acute graft-versus-host disease was observed. Patients experienced minimal toxicities, with typical mucositis and no veno-occlusive disease. Median neutrophil engraftment was 11 days (range 11–13 days) with robust donor chimerism up to 2 years post-HSCT (99–100%), meeting the primary endpoints of the study. Briquilimab cleared in each patient before HSCT without the need for adjustment. Red blood cell, platelet and lymphocyte recovery was comparable to previous reports with TCRαβ+ T cell-depleted and CD19+ B cell-depleted grafts. All patients are alive and well with resolution of earlier chromosomal breakage abnormalities in peripheral blood lymphocytes post treatment. These data demonstrate the broad potential of this protocol in maintaining HSCT efficacy while reducing toxicity. The phase 2 trial is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04784052).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Donor-derived (allogeneic (allo-)) hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) can be curative for a diverse array of genetic and acquired hematological conditions including bone marrow failure (BMF), hemoglobinopathies and malignancies. However, current allo-HSCT protocols rely on DNA-damaging total body irradiation (TBI) and/or chemotherapy-based conditioning, which result in short- and long-term toxicities and predispose patients to secondary malignancies1. Although lower targets for conditioning drug exposures have improved outcomes for allo-HSCT, the complications associated with these regimens remain problematic, particularly in patients with inherited cancer predispositions and/or heightened sensitivities to DNA-damaging agents. An alternative approach that eliminates genotoxic irradiation and myeloablative chemotherapy conditioning could improve the safety and efficacy of allo-HSCT and expand the pool of patients for whom allo-HSCT is indicated.

We have developed a new protocol that uses a TBI- and busulfan-free antibody-containing conditioning regimen comprising: (1) briquilimab (also known as JSP191), an aglycosylated humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks CD117 (also known as c-KIT), a surface receptor tyrosine kinase expressed on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)2,3,4, combined with (2) rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG; also known as Thymoglobulin), low-dose cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and rituximab immunosuppression to prevent immunological rejection and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) reactivation. Patients are then transplanted with TCRαβ+ T cell-depleted and CD19+ B cell-depleted HSPCs (αβ-depleted HSPCs), a stem cell therapy that enhances donor hematopoietic and immune reconstitution, decreases graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and expands the donor pool, enabling the use of more immune disparate donors5,6,7. In addition, we performed robust clinical, pharmacological and immunological patient monitoring to minimize allo-HSCT comorbidities (Extended Data Fig. 1). Although independent studies have demonstrated successful outcomes with each of these modalities alone4,5, the combination of targeted HSPC conditioning using briquilimab and transient immunosuppression, together with transplantation of αβ-depleted HSPCs has never been tested in any disease setting. Moreover, to date, in allo-HSCT for patients who are immunocompetent, briquilimab has been used only with inclusion of genotoxic TBI in the conditioning regimen8. Instead, we have developed a TBI- and busulfan-free antibody-containing approach to enable haploidentical allo-HSCT in immunocompetent patients with reduced toxicity (Fig. 1). Although we have pioneered this protocol in people with Fanconi anemia (FA) as a result of the exquisite sensitivity of these individuals to genotoxic conditioning, its broader application may benefit treatment of numerous nonmalignant and malignant hematological diseases.

a, CONSORT diagram displaying all three patients who were enrolled and screened, with each undergoing conditioning, transplantation and 2 years of follow-up (f/u) on the phase 1b study. b, Schematic displaying treatment utilized with a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen that was irradiation- and busulfan-free, consisting of the anti-CD117 monoclonal antibody (mAb) briquilimab, rATG, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab. The graft used for HSCT was obtained from the peripheral blood of a haploidentical family member after filgrastim and plerixafor mobilization and apheresis, and was subsequently infused after depletion of TCRαβ+ T cells and CD19+ B cells. All three patients have fully completed the phase 1b study with 104 weeks of follow-up. Schematic in b created using BioRender (https://biorender.com). aATG and fludarabine immunosuppression drug monitoring. bOnly given if <40 CD34+ cells µl−1 in peripheral blood. cATG dosing was adjusted between patients: patient 1 at 2.5 mg kg−1 day −9 to −7, all others 4 mg kg−1 day −10 to −8.

FA is caused by ≥23 genetic subtypes and results in an impaired ability to repair DNA interstrand crosslinks and stalled replication forks, thus predisposing people to BMF and malignancies. Given that ~80% of people with FA show signs of progressive BMF by age 12 years9,10,11,12,13, allo-HSCT is routinely used in these patients and is the only proven curative treatment for FA hematological disease. The only alternative curative treatment that is currently being explored is autologous ex vivo lentiviral FANCA gene therapy, although this is available only for people diagnosed with FA-A mutations that are early in their disease course before development of severe BMF14. Current allo-HSCT protocols for people with FA without matched sibling donors commonly utilize conditioning containing myeloablative chemotherapy and/or TBI followed by transplantation with CD34+ HSPCs—a regimen that has been shown to eliminate the hematological manifestations of this disease15. However, for people with FA, this protocol also results in substantial morbidity and mortality, with most patients experiencing short- and long-term toxicities, including mucositis, organ damage, prolonged immune compromise leading to severe infections, GvHD, infertility and secondary malignancies15. Although these toxicities occur in all patients with allo-HSCT under current treatment regimens, they are exacerbated in people with FA as a result of their inability to repair the DNA damage induced by the genotoxic chemotherapy and irradiation used in traditional conditioning regimens16. Furthermore, people with FA who develop GvHD post-allo-HSCT have an even greater risk of secondary malignancies, so minimizing the occurrence of GvHD is of critical importance in this population15,16,17. For this reason, allo-HSCT protocols for people with FA commonly utilize T cell-depleted grafts with serotherapy and reduced-intensity conditioning, although reducing the use of genotoxic conditioning agents has come at the risk of increasing graft rejection18. Recognition of the urgent need to further improve allo-HSCT protocols for people with FA and the promising preclinical data in this disease setting, this indication was ideal for initial evaluation of a combination antibody-containing reduced-intensity conditioning and αβ-depleted HSPC-based allo-HSCT protocol.

The briquilimab-containing reduced-intensity conditioning regimen described was used in combination with familial haploidentical αβ-depleted HSCT and evaluated in people with FA who have severe BMF requiring allo-HSCT in a single-center, investigator-initiated, phase 1b/2a clinical trial. Here we reported the completed analysis of the phase 1b portion of our on-going study with three children with FA who each received this TBI-free and busulfan-free αβ-depleted HSCT treatment and underwent 2 years of follow-up (NCT04784052).

Results

This report details outcomes for the patients treated on the phase 1b single-arm clinical trial investigating 0.6 mg kg−1 of briquilimab in combination with rATG, cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and rituximab conditioning with haploidentical αβ-depleted HSCT. Between 7 December 2021 and 1 December 2023, three patients were enrolled and screened. All patients subsequently underwent conditioning and transplantation, each completing 2 years of follow-up (Fig. 1). Although the safety profile of the briquilimab investigational product has been very favorable to date in parallel studies of other individuals, given that this was the first use in people with FA and no TBI was used, unlike in other studies with immunocompetent individuals, the phase 1b safety run-in evaluation (n = 3 participants) was specifically conducted to assess the safety of the investigational product briquilimab in people with FA alongside treatment with αβ-depleted HSPCs and the reduced-intensity preparative regimen. The primary endpoint of the study was the safety and early efficacy of αβ-depleted HSPC grafts in combination with the reduced-intensity preparative regimen containing briquilimab, rATG, cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and rituximab in people with FA. Secondary endpoints included pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of briquilimab, rATG and fludarabine, incidence of acute regimen-related toxicities and the kinetics of hematopoietic and immune recovery.

Patients

Three patients with FA, all aged ≤10 years, of differing races and each carrying distinct mutations in the FANCA gene were enrolled, screened for the study and treated (Table 1 and Extended Data Table 1). Patients 1 and 2 had no previous blood or platelet transfusions; patient 3 had received more than ten red blood cell (RBC) and platelet transfusions (Table 1 and Extended Data Table 1). All patients had BM evaluation before treatment showing normal BM cytogenetics and no concerning mutations on molecular testing (Extended Data Table 1). Patients also had no notable previous infection history. All three patients completed screening and met eligibility criteria (Extended Data Table 2) and proceeded with treatment per the clinical trial schema (Fig. 1). Treatment of these patients, each with 2 years of follow-up, completed the phase 1b portion of this trial.

Patient disposition: treatment and outcome assessments

To deplete host HSPCs, all patients were given briquilimab at 0.6 mg kg−1 on day −12. Real-time drug levels were collected to evaluate the clearance of briquilimab before donor allograft infusion (see Methods for details including dosing justification). Subsequently, rATG, cyclophosphamide, and fludarabine were given for lymphodepletion to prevent immunological rejection and rituximab was given to prevent EBV reactivations (Fig. 1b and Table 1). PK for rATG and fludarabine was monitored retrospectively to optimize immunosuppression for subsequent patients (Extended Data Fig. 2). For patient 1, rATG was given on days −9, −8 and −7 at 2.5 mg kg−1. For patients 2 and 3, the rATG dose was adjusted to 4 mg kg−1 on days −10, −9 and −8. Fludarabine was given at 35 mg m−2 on days −5, −4, −3 and −2 for all patients. All patients also received 10 mg kg−1 day−1 of cyclophosphamide on days −5, −4, −3 and −2. On day −1, 200 mg m−2 of rituximab was given to all patients to specifically prevent post transplantation EBV-induced lymphoproliferative disorder, as has been previously reported19.

The αβ-depleted HSPCs were obtained from 5 out of 10 human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched familial donors per the clinical trial schema (Fig. 1b). Donors were evaluated for protocol eligibility (Extended Data Table 2) and subsequently received filgrastim and plerixafor for mobilization of stem cells, followed by apheresis. The apheresis products were TCRαβ+ T cell- and CD19+ B cell-depleted using a CliniMACS Plus system as previously described5,20,21 and infused fresh the following day to all patients. The αβ-depleted HSPC graft CD34+ cell dose target was >10 × 106 cells kg−1 and the TCRαβ+ cell dose target was <1 × 105 cells kg−1. Patients received no pharmacological GvHD prophylaxis.

Patients were monitored for infusion-related toxicities and tissue damage from the conditioning regimen such as mucositis and veno-occlusive disease of the liver (VOD). Donor engraftment was determined as time to reach absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 500 cells μl−1 for 3 days consecutively with >1% presence of donor cells (Methods). Patients were assessed for GvHD throughout the hospital stay and post transplantation period and were discharged when they met outpatient criteria. BM evaluation was consistently performed at 1, 6, 12 and 24 months post transplantation to assess hematopoietic reconstitution and donor chimerism. All other standard post transplantation follow-up, including evaluations for immune reconstitution, was conducted as per standard transplantation protocols.

Primary outcomes: safety and engraftment

All patients received conditioning containing briquilimab and no briquilimab-related toxicities of any grade were observed during either briquilimab infusion or the peri-transplantation period (Table 1 and Extended Data Table 3). Subsequently, all patients received a 5 out of 10 HLA-matched parental αβ-depleted HSPC graft, which was obtained without complications (Table 1). All CD34+ doses were >10 × 106 cells kg−1 (mean 15.9 × 106 cells kg−1; range 14.24–17.17 × 106 cells kg−1) and TCRαβ cell doses were <1 × 105 cells kg−1 (mean 0.13 × 105 and (0.11–0.18) × 105 cells kg−1) as per protocol (Table 1) and no αβ-depleted HSPC graft-related toxicities of any grade were observed during graft administration (Extended Data Table 3). All transplanted patients had a typical immediate hospital course as expected for allo-HSCT patients. Although they each developed pancytopenia after conditioning, all patients engrafted promptly with ANC > 500 mm−3 for 3 days consecutively (Extended Data Table 4). Engraftment was maintained for the full length of follow-up and no graft rejection was observed, unlike the earlier TBI dose de-escalation study in FA with alternative donors where two of two patients who received 150 cGy of TBI with allo-HSCT had graft rejection18.

Secondary outcomes: conditioning pharmacokinetics

PK data for briquilimab, rATG and fludarabine are reported in Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 2. Patients received briquilimab at 0.6 mg kg−1 administered as a single intravenous (i.v.) infusion. The serum concentration of briquilimab was determined after its administration by a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Whole blood was obtained at various times after the briquilimab infusion with a goal trough level of <1,500 ng ml−1 on the day of stem cell infusion that was achieved in each patient (Fig. 2). Serum samples for rATG PK analysis were collected beginning on the day of rATG infusion: pre-infusion and 15 min after the end of the first infusion, 15 min after the end of the second infusion, 15 min after the end of the third infusion, on the day of the transplantation (transplant day 0) before graft infusion and, subsequently, 1 week and 2 weeks after graft infusion. For rATG, pre-HSCT and post-HSCT, AUC goals were >40 a.u. day−1 ml−1 and <30 a.u. day−1 ml−1, respectively22,23,24. Patient 1 received 2.5 mg kg−1 for 3 doses starting on day −9 and had an estimated pre-HSCT AUC below target (14.6 a.u. day−1 ml−1), whereas the post-HSCT AUC was within the target range (2.31 a.u. day−1 ml−1). Given the low pre-HSCT AUC for patient 1, rATG was increased for patients 2 and 3 to 4 mg kg−1 for 3 doses, starting on day −10 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Serum samples for fludarabine PK analysis were collected, beginning on the first day of fludarabine infusion: pre-infusion and 15 min, 1, 3 and 6 h after the end of the first infusion. Cumulative AUC for patient 1 was within the previously published goal25,26 and the same i.v. dosing of 35 mg m−2 for 4 doses was maintained for patients 2 and 3 (Extended Data Fig. 2b).

Secondary outcomes: engraftment kinetics

All patients engrafted with ANC > 500 cells μl−1 by a median of 11 days (range 11–13 days) and platelet engraftment by a median of 13 days (range 11–14 d) (Fig. 3a,b, Extended Data Table 4 and Extended Data Fig. 3). The last post-HSCT packed RBC transfusion was on or before day +8 in all patients (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Table 4 and Extended Data Fig. 3). Neutrophil and platelet engraftment kinetics appeared similar or improved compared with previously reported CD34+-enriched grafts15. All patients also showed rapid and sustained donor cells in all cell-lineage compartments post transplantation: HSPCs (CD34+), myeloid cells (CD15+), B cells (CD19+), T cells (CD3+) and natural killer (NK) cells (CD56+). Specifically, at both 30 days post transplantation and completion of study follow-up (2 years), 92–100% donor chimerism was observed in all patients in all cell lineages (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Table 4). Notably, this far exceeded the initial primary endpoint of >1% donor CD15 chimerism by day +42 with persistent engraftment at day +100. Furthermore, immune recovery was similar to earlier reports with αβ-depleted HSPC grafts19 with increased T cells, B cells and NK cells over study visits (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 4). Post transplantation resistance to DNA damage was also observed in peripheral blood lymphocytes from all patients, with resolution of chromosomal breakage on exposure to the clastogenic agent diepoxybutane (DEB) (Fig. 4b).

a–c, All three patients promptly engrafted neutrophils (a), platelets (b) and RBCs (c) within 2 weeks of HSCT with resolution of earlier cytopenia. d,e, Near-complete multilineage donor chimerism at both short- and long-term timepoints post-HSCT in peripheral blood (PB) (d) and bone marrow (BM) (e). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Each data point represents the average of measurements from three patients.

a, Efficient immune recovery of CD3+ T cells, CD19+ B cells and CD16+CD56+ NK cells post allo-HSCT, comparable to other T cell-depleted HSCT approaches. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Each data point represents the average of measurements from three patients. b, Peripheral blood chromosomal breakage studies using the clastogenic agent DEB showing FA-related chromosome breakage in lymphocytes from all patients at screening. Chromosomal breakage was normalized in lymphocytes in each of the patients post-HSCT, with no notable breakage, resembling control values from unrelated healthy donors. Data are presented as mean values, with each point representing the average from 50 cells.

Secondary outcomes: adverse events

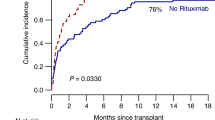

All phase 1b patients completed the 2-year study with 100% event-free survival (Fig. 5a) and are now being followed on our institutional, long-term follow-up protocol. All patients experienced mucositis, grade 2 or 3, typical for allo-HSCT protocols, which was likely related to the inclusion of cyclophosphamide in the conditioning regimen; most required pain medications with nutritional support by the enteral or parenteral route in settings where nasogastric tube placement was not tolerated; none developed VOD (Extended Data Table 3). Patient 1 developed fever around day +5 without any evidence of infection based on laboratory testing, blood cultures and imaging. In the haploidentical graft setting, there was initial concern that this was a sign of rejection, although the patient was ultimately found to have 100% donor chimerism. While awaiting these test results, the patient was started on corticosteroids and tacrolimus and his blood counts came up steadily with neutrophil engraftment on day +11, which remained stable after discontinuation of immunosuppression. The subsequent patients each had robust blood count recovery without post transplantation immunosuppression (Fig. 3a–c and Extended Data Fig. 3). Given that all patients received pre-transplantation immunosuppression, viral reactivations including cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6 and/or BK hemorrhagic cystitis were detected in two of the three patients (66%) (Extended Data Table 3). Both of these patients received antiviral therapy with resolution of viral reactivations and none developed invasive viral disease (Extended Data Table 5). In addition, several patients experienced typical seasonal upper respiratory viral infections, which were managed with supportive care (Extended Data Table 5). Concurrent with a rhino- and enteroviral upper respiratory infection, patient 2 developed immune-mediated hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia 5 months after transplantation, which has previously been reported with allo-HSCT27. At the last follow-up she had completely recovered and maintains full donor chimerism after completing combination drug therapy (Extended Data Table 4). Despite the lack of pharmacological GvHD prophylaxis, no acute GvHD of any grade was observed in any of the patients (Fig. 5b). Patient 3 exhibited moderate chronic skin and gastrointestinal GvHD in the setting of poor diet management and treatment noncompliance, which required systemic immunosuppression (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Table 3).

All three patients were treated without developing any investigational product severe adverse events. a, All patients remain engrafted with 100% event-free survival (EFS) and no primary or secondary graft failure, which is most typically observed within 6 months of HSCT despite the use of haploidentical, mobilized, peripheral blood donor grafts. b, No acute GvHD observed in any patient. c, Chronic GvHD observed in only one patient.

Exploratory outcomes: disease resolution

Exploratory corollary research studies were also pre-specified and performed using BM obtained pre- and post-HSCT to assess for restoration of BM hematopoiesis and resistance to DNA damage. All patients tested were noted to have a marked reduction in BM colony-forming capacity in HSPCs obtained at screening (P = 0.001), which improved by 24 weeks post-HSCT to levels comparable to healthy control samples (P = 0.38; Extended Data Fig. 5a). Complete sensitivity of BM HSPCs to the DNA-damaging agent mitomycin C (MMC) at 10 nM (P = 0.0001) and 50 nM (P = 0.037) was also observed in all patients at screening (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Post-HSCT, MMC resistance in all patients normalized and was comparable to healthy control samples (Extended Data Fig. 5b). No BM concerns have been observed post transplantation, as assessed by clinical flow cytometry, cytogenetics and molecular HEME-STAMP testing.

Discussion

Allo-HSCT is a curative treatment for diverse blood and immune diseases and remains the only proven modality to treat progressive BMF in people with FA, irrespective of genotype or disease state. However, allo-HSCT with standard regimens increases the already high risk of malignancy in people with FA by more than fourfold and accelerates the median age of onset by 16 years17,28. Longitudinal assessment of people with FA post historic allo-HSCT treatments has documented development of solid tumors in all individuals by age 40 years17. Previous attempts at removing TBI from the conditioning regimen in people with FA without matched sibling donors allowed TBI dose reduction, but elimination was not possible because of the high rates of graft rejection16,18 and alternative regimens have simply replaced TBI with genotoxic busulfan chemotherapy29.

Here we showed that the anti-CD117 monoclonal antibody briquilimab, in combination with lymphodepletion, allows elimination of TBI- and busulfan-based conditioning, achieving robust donor HSPC engraftment with restoration of hematopoiesis in individuals with diverse FANCA gene mutations. To date, all patients treated attained rapid blood count recovery with near-complete and persistent donor hematopoietic chimerism without the use of TBI or busulfan. Furthermore, together with careful patient monitoring and aggressive treatment of viral reactivations, our protocol has led to a successful post transplantation course in these individuals with minimal treatment-related toxicities. Importantly, although briquilimab has been reported to enable immune reconstitution without notable toxicity in immunocompromised individuals with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID; NCT02963064)4, our trial shows successful engraftment without the use of TBI in individuals with competent immune systems, thus establishing an effective TBI-free immunosuppression backbone that can prevent immunological graft rejection. Similarly, although αβ-depleted HSPC grafts have demonstrated success across numerous disease indications, including FA19, such grafts have never been tested in the context of a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen containing an HSPC-targeted antibody.

Through completion and reporting of the phase 1b portion of this clinical trial, we showed that the combination of an anti-CD117 antibody coupled with immunosuppression and a megadose of HSPCs can overcome the engraftment barrier in immunocompetent recipients even with haploidentical donor grafts. This unique approach may lay the foundation to enabling transplantation for people with FA at all stages of disease, including before severe BMF onset, which could further minimize risks of an adverse transplantation course preceded by pre-transplantation infections and blood product requirements. In addition, although FA is a rare disease (~1 in 136,000 newborns in the USA) and our patient population is small, the three patients treated (one male patient, two female patients) identify as white American, Asian American or African American, thus demonstrating diversity of sex and ethnicity. In addition, considering the success of this treatment regimen in these diverse individuals with FA, this innovative approach may also prove effective and advantageous for people with other BMF disorders or severe hematopoietic diseases.

The interpretation of the results in this phase 1b study is limited by the fact that this is a single-arm study and has a small population size challenging statistical analysis. However, each patient in our study met the primary outcome of safety, exhibiting lack of investigational product toxicities with sustained donor engraftment, unlike the earlier TBI dose de-escalation study in people with FA with alternative donors, where graft rejection was seen in all patients treated with 150 cGy of TBI and allo-HSCT18. Moreover, trends toward improved efficacy with this protocol are also evident despite the small phase 1b cohort size. In light of these promising results, additional patients are now being treated with continuation of this protocol in the phase 2a study. It is important to note that, despite the use of a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen containing briquilimab with no TBI or busulfan, mucositis was still observed in all patients. Thus, the conditioning agents employed can still lead to tissue damage in the sensitive FA setting, which may contribute to the development of secondary malignancies in the future—a long-term evaluation that will only be feasible several decades from now. Although this tissue damage is likely linked to the use of cyclophosphamide and/or fludarabine, we cannot determine the specific contributions of each agent within the combination regimen. This tissue damage also underscores the need for continued improvements to transplantation protocols for these and other individuals. As such, our long-term goal is to achieve an effective and fully non-genotoxic, antibody-based conditioning regimen. This trial lays the groundwork for future innovations in protocols. If a conditioning regimen that is entirely free of genotoxic agents is developed, it could even facilitate proactive intervention for individuals predisposed to cancer before any disease-progression or transformation occurs.

The development of non-genotoxic conditioning regimens has been a high-priority objective, especially for allo-HSCT grafts that have historically required more intensive conditioning. Accordingly, we have developed this protocol for people with FA, although reduced exposure to genotoxic agents would be of benefit to many different individuals who require stem cell transplantation for various diverse blood and immune diseases. The study NCT04784052 presents the potential of this antibody-containing protocol to become standard therapy for FA and lays the foundation for further protocol innovation and follow-on studies in other disease indications.

Methods

Ethics statement for use of stem cells

The work outlined in this manuscript adheres to the 2016 ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Applications of Stem Cells and has been approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board (IRB; IND-27167). We confirm that informed assent or consent was obtained from all recipients and donors of HSPCs. Conditions of stem cell donation are detailed in the paper and the clinical protocol.

Study design and procedures

We obtained US Food and Drug Administration and Stanford IRB approval for a single-center investigator-initiated phase 1b/2a clinical trial (NCT04784052) to test this protocol in pediatric and adult individuals with FA who have severe BMF requiring allo-HSCT. Patients were recruited through internal institutional referrals or external referrals by care providers. Patients and their respective identified donors gave informed consent before enrolling within the trial. Once enrolled, patients and donors underwent screening to confirm eligibility before proceeding to HSCT procedures. Given the small study size, sex was not considered in the study design and patients of any sex were included as determined by their self-reporting. No compensation was provided for participating in the trial. Participants were reimbursed for travel expenses related to research activities. Any procedures performed solely for research purposes were paid for by the study.

This single-arm trial enrolled transplant-naive individuals with FA in BMF but without myelodysplasia or malignancies who had available 5 or more out of 10 HLA-matched related or unrelated donor(s). All patients were given a one-time dose of briquilimab at 0.6 mg kg−1 followed by a reduced-intensity preparative regimen consisting of three doses of 4.0 mg kg−1 of rATG (with 2.5 mg kg−1 for patient 1), four doses of 10 mg kg−1 of cyclophosphamide, four doses of 35 mg m−2 of fludarabine and one dose of 200 mg m−2 of rituximab. The primary purpose of the study was to determine the safety and early efficacy of briquilimab as part of a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen.

Enrollment of patients began 7 December 2021 with phase 1b screening completed on 1 December 2023; the data cutoff reported here is 20 March 2025 with all three patients being reported to have completed 2 years (104 weeks) of follow-up. Data were collected as described in the study-specific clinical protocol. Additional details for both patients and donors are provided on the ClinicalTrials.gov database (NCT04784052) and Extended Data Table 2. The full phase 1b/2a study is powered to demonstrate non-inferiority to donor engraftment, observed with alternative historic transplantation regimens containing irradiation or busulfan used in this patient population.

Patient inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) FA diagnosis as demonstrated by abnormal chromosome breakage studies with increased sensitivity to MMC or DEB and at least one mutation in a known Fanconi-associated gene; (2) BMF (defined by reduction in at least one cell line on two separate occasions at least 1 month apart, for example, platelet count <100,000 per mm3, hemoglobin <9 g dl−1 and/or ANC <1 ,000 per mm); (3) age ≥2 years; (4) a related or unrelated consenting donor with at least 5 or more out of 10 HLA-match available for apheresis; (5) organ function defined as: (i) serum creatinine <2.0 mg dl−1 and corrected creatinine clearance/cystatin >60 ml−1 min−1 1.73 m−2 without dialysis, (ii) forced expiratory volume in 1 s, forced vital capacity and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide corrected for hemoglobin and volume, >50% predicted by pulmonary function tests, (iii) for patients unable to cooperate for pulmonary function tests, criteria are no evidence of dyspnea at rest, no exercise intolerance and no requirement for supplementary oxygen with SpO2 > 93%, (iv) shortening fraction ≥29% or ejection fraction ≥45% by echocardiogram, (v) serum total bilirubin of <4× upper limit of normal (ULN), (vi) alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase <5× ULN and (vii) prothrombin time international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time <1.5× ULN; (6) life expectancy of at least 2 years; (7) patients of childbearing potential must have been willing to use an effective contraceptive method for the duration of the peri-transplantation conditioning through hematopoietic recovery; and (8) patients and/or parents or legal guardians must have been able to provide written informed consent and authorize use and disclosure of personal health information in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Patient exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if any of the following criteria were met: (1) patients with available and consenting 10 out of 10 HLA-identical sibling donors for apheresis or BM collection; (2) patients with any acute or uncontrolled infections at the time of enrollment, including bacterial, fungal or viral; (3) patients who are seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus type I or II or human T cell lymphotropic virus type I or II; (4) patients receiving any other investigational agents or other biological therapy, chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 14 days of enrollment; (5) patients with any active malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome or other concerns for high-risk BM disease; (6) patients who had received androgens in the last 3 months; (7) pregnant or lactating women; (8) women who were nursing and did not wish to discontinue breast-feeding; (9) Lansky’s or Karnofsky’s performance score <50%; (10) any other medical condition or history that, in the opinion of the principal investigator (PI), could pose a major safety risk to the participant or jeopardize the integrity of the study; or (11) patients who, in the opinion of the PI, may not be able to comply with the safety monitoring requirements of the study.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was the safety and efficacy of TCRαβ+ T cell-depleted and CD19+-depleted hematopoietic grafts and a reduced-intensity preparative regimen containing briquilimab in combination with rATG, cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and rituximab in patients with FA, according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v.5.0, as assessed by lack of grade 3 and 4 treatment-emergent adverse events related to either product, with the ability to achieve donor engraftment after allogeneic transplantation, defined as an ANC > 500 per mm3 for three consecutive laboratory values obtained on different days by day +42 post-cell transplantation with >1% CD15+ donor chimerism at the same rate or better (non-inferiority) compared with alternative HSPC transplantation regimens.

The secondary endpoints of the trial included the PK properties of briquilimab, rATG and fludarabine as assessed by serum concentrations in the peripheral blood, the incidence of acute regimen-related toxicity as assessed via mucositis and VOD scoring using the CTC and modified Seattle criteria, and post transplantation hematopoietic and immune recovery, as assessed by hemoglobin >8 g dl−1 and platelets >20,000 dl−1 without transfusion support for greater than 7 days post-graft transplantation. The quantitative properties of donor engraftment were also assessed by peripheral blood (total, CD15+, CD3+, CD19+, CD56+ and CD34+) and BM (total and CD34+) chimerism by STR (short tandem repeat) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis according to the schedule of events. Furthermore, the immunological recovery after transplantation of cells was specifically determined by the time to reach >200 μl−1 of CD3+ T cells as assessed by percentage and absolute numbers of T (CD3), B (CD19) and NK (CD56) cells via complete blood count (CBC) differential studies and flow cytometry. The incidence of grade I–IV acute GvHD at day +100 after graft transplantation was assessed using the Magic Criteria Grading scale administered on study visits, through day +100, according to the schedule of events and the incidence and severity of chronic GvHD after day +100 through to week +104, as assessed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Project. Last, disease-free survival was assessed by patient survival with resolved DEB-induced chromosomal breakage abnormalities in peripheral blood lymphocyte cultures.

Multiple protocol amendments were conducted throughout the study to ensure optimal study design. Most notably, the briquilimab threshold was increased from 500 ng ml−1 to 1,500 ng ml−1 at the guidance of the briquilimab drug supplier.

Drug administration, monitoring and pharmacokinetics

Briquilimab is a humanized aglycosylated immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody directed against CD117 that inhibits stem cell factor signaling and is manufactured using Chinese hamster ovary cells. There are no N-linked glycans on briquilimab due to an intentional Asn297Gln substitution and therefore briquilimab has no antibody-dependent, cell-mediated, FcγR binding or complement-dependent cytotoxicity activity. Briquilimab was given intravenously at 0.6 mg kg−1 on day −12, a dose derived from a clinical trial evaluating briquilimab in patients with SCID (NCT02963064)1, showing that these conditions consistently lead to serum levels <1,500 ng ml−1 and supported the engraftment of donor HSPCs. To ensure that goal clearance of briquilimab was achieved, PK levels were measured in real time from samples collected at 5 min after the end of briquilimab infusion and 6, 24, 48, 72, 96, 144, 192 and 240 h after the start of the briquilimab infusion. Serum concentrations of briquilimab were measured using a validated ELISA-based assay by Eurofins Pharma Bioanalytics Services, and clearance was estimated by standard noncompartmental and nonlinear, mixed-effect modeling methods. Per the protocol, a predicted briquilimab serum concentration of <1,500 ng ml−1 was required for graft infusion with a goal of <500 ng ml−1. Although no concerns about briquilimab clearance were observed, potential protocol adjustments that could be considered in this scenario included delaying donor graft infusion or altering the mobilization and apheresis of the donor. The PK for briquilimab is shown in Fig. 2.

rATG for patient 1 was given intravenously on days −9, −8 and −7 at a dose of 2.5 mg kg−1. For patients 2 and 3, the rATG dose was modified to 4 mg kg−1 on days −10, −9 and −8. The rATG PK samples were collected at baseline, 15 min after the end of each infusion, on stem cell infusion day and 1 and 2 weeks posttransplantation. Samples were centrifuged, frozen and shipped to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Immune Discovery and Modeling Service (MSKCC IDMS). The rATG plasma concentrations were determined using validated flow-cytometry-based assay, then pre- and post-transplantation AUCs were estimated using the population PK model22 with InsightRx dose optimization software. A pre-transplantation AUC > 40 a.u. day−1 ml−1 (refs. 22,23) and post-transplantation AUC < 30 a.u. day−1 ml−1 (ref. 24) were considered optimal exposure. PK for rATG is shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a.

Fludarabine was given intravenously at 35 mg m−2 on days −5, −4, −3 and −2. Fludarabine concentrations were collected at baseline, 15 min, 1 h, 3 h and 6 h after infusion of the first dose. Samples were centrifuged, frozen and shipped to MSKCC IDMS. Fludarabine plasma concentrations were determined using validated liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry assay and cumulative AUCs were estimated using the population PK model25 with InsightRx dose optimization software. A cumulative AUC in the range 15–25 mg h−1 l−1 was considered to be adequate exposure26. The PK for fludarabine is shown in Extended Data Fig. 2b.

Doses of medications were rounded per institutional chemotherapy rounding policy to the closest vial size, when applicable.

Clinical assessments

Germline gene testing

Peripheral blood samples from all individuals were collected and processed for single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels) and copy number variations (CNVs) using NGS (Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer) with the Blueprint Genetics Comprehensive Hematology Panel v.5 Plus Analysis (Blueprint Genetics) by Quest Diagnostics. The comprehensive hematology panel included 270 gene targets and covered 3,897 exons or regions with a median coverage depth of 184 and up to 20× depth >99.87%. The panel had a reported detection sensitivity of 99.89% for SNVs, 99.2% for indels ranging from 1 bp to 50 bp, 100% for 1-exon deletions and 98.7% for 5-exon CNVs. The specificity is reported to be >99.9% for most variant types. This diverse hematology panel was utilized to assess for mutations in known FA genes and to understand predisposition to potential concurrent genetic hematological diseases that could make patients ineligible for treatment or confound the results.

Myeloid mutation HEME-STAMP assessment

DNA was extracted from whole BM aspirates for the analysis of SNVs and short indels. Targeted NGS was performed on 203 genes, either partially or fully, using the Stanford Actionable Mutation Panel for Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Malignancies30 on an Illumina platform (Heme-STAMP v.4.3.1, Molecular Pathology). Genomic alignment was performed against the GRCh37 (hg19) assembly of the human genome. The assay achieves a minimum analytical detection limit of 5% for SNVs and indels, as well as a minimum analytical detection limit of 5% for variant allele fraction. HEME-STAMP testing was performed on all BM samples, both at screening and post transplantation.

Chromosomal breakage

White blood cells were collected from peripheral blood of all patients at screening and post transplantation (patient 1 at 18 months, patient 2 at 12 months and patient 3 at 6 months). Assays were performed in the Stanford Cytogenetics CLIA-approved laboratory (Stanford Blood Center). Peripheral blood was cultured per standard protocols with the clastogenic agent DEB at 0.1 μg ml−1 to induce FA-related chromosome breakage. Breakage analysis was performed on unbanded chromosome preparations; 50 cells each were screened for chromosome breakage and compared with values from negative control samples of unrelated healthy donors.

Chimerism testing

White blood cells were collected from peripheral blood or BM aspirates at specified timepoints after transplantation and isolated using a Ficoll gradient. Chimerism was assessed by analyzing polymorphisms of STRs in DNA samples extracted from the white blood cells26. These cells were positively selected for CD3+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, CD15+ granulocytes, CD56+ NK cells and CD34+ HSPCs using an automated cell separator instrument (RoboSep-S, STEMCELL Technologies). Chimerism was calculated with a threshold sensitivity of approximately 1% for donor-type cells. Testing was conducted by the Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics Laboratory (Stanford Blood Center).

Colony-forming cell assay

Whole BM aspirates were obtained at specified timepoints and RBCs were removed by red cell lysis (STEMCELL Technologies). Subsequently, the clonogenic potential of progenitors was characterized in a research assay by seeding cells at 2 × 104 and/or 2 × 105 cells (depending on sample availability) per well in a methylcellulose solution (H4034 Optimum, STEMCELL Technologies), with and without 10 nM or 50 nM MMC (MilliporeSigma). Colony scoring was conducted on day 14 using an automated colony-counting instrument (STEMvision, STEMCELL Technologies) and was manually verified for accurate colony counts. The counts reported represent the average measured counts from three technical replicates per sample. Percentage MMC resistance was calculated as the number of surviving cells in MMC-treated samples divided by the number in untreated samples from a condition with either 2 × 104 or 2 × 105 cells plated per well. To understand colony-forming capacity in healthy children, parallel assays were conducted from control pediatric patients who served as matched sibling donors and had BM isolated for transplantation into sibling recipients in different disease settings. Importantly, this assay is not standardly conducted post allo-HSCT and it is unknown whether clonogenic potential in this assay was typically restored post standard HSCT in patients with FA.

Statistics and reproducibility

This study was designed as a non-randomized phase 1b/2a trial design with the group size chosen to reflect the relative rarity of the disorder. The full study was powered to demonstrate non-inferiority to donor engraftment observed with alternative transplantation regimens in this patient population containing irradiation or busulfan. Data from each individual patient were tabulated and data from the study have been summarized with descriptive statistics, including means, s.d. values, medians, minima and maxima for continuous variables, the number of participants and percentage in each category for categorical variables as appropriate. No data were excluded from the analyses. Data were not disaggregated for sex or gender because of the small size of the phase 1b study. Data were stored in a Medrio clinical data management system for electronic data capture and analyzed using Prism software (v.10.2). Given that this was a single-arm study intended to be compared with historical outcomes, no direct comparison between treatment groups on this specific study was possible. However, the primary efficacy outcome of the study is that the proportion of patients achieving donor engraftment without graft failure is intended to be compared with the historical data reported from the 150-cGy TBI cohort of the dose de-escalation study in FA, which is the lowest-dose TBI study published to date with alternative donors18. The primary outcomes of these studies will be compared using a one-sided Fisher’s exact test with the exact (Clopper–Pearson) method to determine the confidence interval. The secondary outcomes of engraftment kinetics will be compared with the 300-cGy TBI CD34+ HSCT study, with alternative donors15 using Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. However, the phase 1b study is intended to assess safety and these tests will be applied once the larger dataset through the phase 2a study is available. In addition, the phase 1b BM hematopoiesis corollary studies were performed in triplicate and compared using parametric, unpaired Student’s t-test (two-sided) for statistical analysis.

Inclusion and ethics statement

Our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. This work was conducted in collaboration with primary care providers and referral of subspecialty providers, with patient referral from throughout the United States. All individuals who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were offered the option to participate, representing a diverse patient population irrespective of gender, race and ethnicity. The protocols of this study have been preregistered and conform to the declaration of relevant US regulations and were approved by the Stanford IRB. We are dedicated to fostering diversity and inclusivity and have taken steps to ensure that our research is carried out with respect and regard for individuals of all races, ethnicities, genders, sexual orientations, abilities and other facets of human diversity.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data and methods for each of the three patients treated are provided within this paper. Upon completion of the clinical trial, all study data will be uploaded to ClinicalTrials.gov and made appropriately available. For any additional questions or any data requests, please contact the corresponding author at aneeshka@stanford.edu with an expected response within 1 week.

References

Bonfim, C. et al. Transplantation for Fanconi anaemia: lessons learned from Brazil. Lancet Haematol. 9, e228–e236 (2022).

Pang, W. et al. Anti-CD117 antibody depletes normal and myelodysplastic syndrome human hematopoietic stem cells in xenografted mice. Blood 133, 2069–2078 (2019).

Kwon, H. S. et al. Anti-human CD117 antibody-mediated bone marrow niche clearance in nonhuman primates and humanized NSG mice. Blood 133, 2104–2108 (2019).

Agarwal, R. et al. JSP191 as a single-agent conditioning regimen results in successful engraftment, donor myeloid chimerism, and production of donor derived naïve lymphocytes in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). Blood 138, 554 (2021).

Bertaina, A. et al. HLA-haploidentical stem cell transplantation after removal of αβ+ T and B-cells in children with non-malignant disorders. Blood 124, 822–826 (2014).

Locatelli, F. et al. Outcome of children with acute leukemia given HLA-haploidentical HSCT after αβ T-cell and B-cell depletion. Blood 130, 677–685 (2017).

Bertaina, A. et al. Unrelated donor vs HLA-haploidentical alpha/beta T-cell- and B-cell-depleted HSCT in children with acute leukemia. Blood 132, 2594–2607 (2018).

Muffly, L. S. et al. Early results of phase 1 study of JSP191, an anti-CD117 monoclonal antibody, with non-myeloablative conditioning in older adults with MRD-positive MDS/AML undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 7035 (2021).

Kutler, D. I. et al. A 20-year perspective on the International Fanconi Anemia Registry (IFAR). Blood 101, 1249–1256 (2003).

Schifferli, A. & Kühne, T. Fanconi anemia: overview of the disease and the role of hematopoietic transplantation. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 37, 335–343 (2015).

Soulier, J. Fanconi anemia. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2011, 492–497 (2011).

Che, R., Zhang, J., Nepal, M., Han, B. & Fei, P. Multifaceted Fanconi anemia signaling. Trends Genet. 34, 171–183 (2018).

Mamrak, N. E., Shimamura, A. & Howlett, N. G. Recent discoveries in the molecular pathogenesis of the inherited bone marrow failure syndrome Fanconi anemia. Blood Rev. 31, 93–99 (2017).

Czechowicz, A. et al. Gene therapy for Fanconi anemia [group A]: interim results of RP-L102 clinical trials. Blood 138, 3968–3969 (2021).

Ebens, C. L., MacMillan, M. L. & Wagner, J. E. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia: current evidence, challenges and recommendations. Expert Rev. Hematol. 10, 81–97 (2017).

MacMillan, M. L. et al. Haematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with Fanconi anaemia using alternate donors: results of a total body irradiation dose escalation trial. Br. J. Haematol. 109, 121–129 (2000).

Alter, B. P., Giri, N., Savage, S. A. & Rosenberg, P. S. Cancer in the National Cancer Institute inherited bone marrow failure syndrome cohort after fifteen years of follow-up. Haematologica 103, 30–39 (2018).

MacMillan, L. et al. Alternate Donor HCT for Fanconi anemia (FA): results of a total body irradiation (TBI) dose de-escalation study. Blood 112, 2998 (2008).

Strocchio, L. et al. HLA-haploidentical TCRαβ+/CD19+-depleted stem cell transplantation in children and young adults with Fanconi anemia. Blood Adv. 5, 1333–1339 (2021).

Chaleff, S. et al. A large-scale method for the selective depletion of αβ T lymphocytes from PBSC for allogeneic transplantation. Cytotherapy 9, 746–754 (2007).

Schumm, M. et al. Depletion of T-cell receptor alpha/beta and CD19 positive cells from apheresis products with the CliniMACS device. Cytotherapy 15, 1253–1258 (2013).

Admiraal, R. et al. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of Thymoglobulin in children receiving allogeneic-hematopoietic cell transplantation: towards improved survival through individualized dosing. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 54, 435–446 (2015).

Admiraal, R. et al. Association between anti-thymocyte globulin exposure and CD4+ immune reconstitution in paediatric haemopoietic cell transplantation: a multicentre, retrospective pharmacodynamic cohort analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2, e194–e203 (2015).

Lakkaraja, M. et al. Antithymocyte globulin exposure in CD34+ T-cell-depleted allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 6, 1054–1063 (2022).

Ivaturi, V. et al. Pharmacokinetics and model-based dosing to optimize fludarabine therapy in pediatric hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 23, 1701–1713 (2017).

Langenhorst, J. B. et al. Fludarabine exposure in the conditioning prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation predicts outcomes. Blood Adv. 3, 2179–2187 (2019).

Barcellini, W., Fattizzo, B. & Zaninoni, A. Management of refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: current perspectives. J. Blood Med 10, 265–278 (2019).

Rosenberg, P. S., Socié, G., Alter, B. P. & Gluckman, E. Risk of head and neck squamous cell cancer and death in patients with Fanconi anemia who did and did not receive transplants. Blood 105, 67–73 (2005).

Mehta, P. A. et al. Radiation-free, alternative-donor HCT for Fanconi anemia patients: results from a prospective multi-institutional study. Blood 129, 2308–2315 (2017).

Busque, S. et al. Mixed chimerism and acceptance of kidney transplants after immunosuppressive drug withdrawal. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaax8863 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The clinical trial including cGMP manufacture and clinical testing of the αβ-depleted HSPC grafts, as well as evaluation of primary, secondary and correlative objectives, was supported by anonymous philanthropic support and funding from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (grant no. CLIN2-14315 to M.P.). Apart from providing funding, the funders had no additional roles in this study. Jasper Therapeutics (https://www.jaspertherapeutics.com) supplied the briquilimab agent and provided sponsored research support to A.C. for study development before initiation of the clinical trial; however, they provided no funding for this investigator-initiated clinical trial. We thank the trial participants and their families, the broad community of individuals with FA, the Fanconi Cancer Foundation (formerly Fanconi Anemia Research Fund) and the Stanford Clinical Trial program for clinical trial support, including R. P. Bartolome, K. Dougall, E. Goodwin, S. Chowdary Kollu, A. Limaye, M. Singh, A. B. Olsen and S. A. Wolf. J.J.B. acknowledges the support of the NIH/National Cancer Center (grant no. P30 CA008748).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in aspects of the study design and conduct, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of study results, and the drafting, critical review and approval of the final version of the manuscript. R.A., A.B., G.S., R.N., M.V.H., E.W., A.S., A.B., J.A.S., W.W.P., K.W., R.P., M.G.R., M.P. and A.C. contributed to study design and protocol initiation. R.A., A.B., E.F.K., J.C., M.W.W., M.P. and A.C. carried out clinical investigations. G.S., N.K., E.I. and H.N.D. provided clinical trial support and obtained and analyzed clinical data. C.S., Y.Y.C., H.W., M.K., G.B., S.S. and A.C. performed and analyzed the corollary studies and analyzed clinical data. J.R.L.-B, L.H. and J.J.B. verified and analyzed the PK data. R.A., A.B., C.S., R.J.P., M.P. and A.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors had access to the study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.B. is a consultant and received honoraria from Miltenyi and Neovii. L.H. is a member of an advisory committee of and received honoraria from Sobi. J.J.B. received honoraria from Advanced Clinical and is a consultant for and received honoraria from Immusoft, Sanofi, Sobi and SmartImmune. J.A.S. and W.W.P. are consultants and current equity holders for Jasper Therapeutics. M.G.R. is a current equity holder for Graphite Biologics, TR1X, Atara and Kamau Therapeutics and a member of their boards of directors or advisory committees. M.P. is a current equity holder for Graphite Biologics, Allogene Therapeutics and Alaunos Therapeutics and a member of their boards of directors or advisory committees; he is also a current equity holder of Kamau Therapeutics and CRISPR Tx. A.C. is a current equity holder of Beam Therapeutics, Dianthus Therapeutics and Editas Medicines; a consultant and/or current equity holder for Fulcrum Therapeutics, GV, Land Medicine and Kyowa Kirin; holds patents and royalties for Inograft Biotherapeutics and is a current equity holder and member of their advisory committee; holds patents and royalties for and research funding from Jasper Therapeutics; holds patents and royalties for Magenta Therapeutics; is a current equity holder for and a member of advisory committees for Permanence Bio and Prime Medicines; has research funding from and is a consultant for Rocket Pharma; and is a current equity holder for Spotlight Therapeutics and Teiko Bio. In addition, A.C. and other authors are inventors on various patents related to antibody-based conditioning. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Markus Grompe and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Anna Maria Ranzoni, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Study Goals and Approaches Used.

Three complimentary goals of avoiding DNA-damage to cells from individuals with Fanconi Anemia, optimizing hematopoietic grafts and close pharmacokinetic monitoring were incorporated in this clinical trial.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Clearance of rATG and Fludarabine in Context of Conditioning Regimen Containing Briquilimab.

Given the graft rejection that was observed in prior dose de-escalation of TBI from FA allo-HSCT protocols, close pharmacokinetic monitoring of rATG and fludarabine was performed to ensure concurrent optimal immunosuppression was administered. a) rATG: Patient 1 received 2.5 mg/kg IV for 3 doses starting on day −9. The pre-HSCT AUC was estimated to be below goal at 14.6 AU*day/mL, while post-HSCT AUC was estimated to be within goal at 2.31 AU*day/mL. Given the low pre-HSCT AUC for Patient 1, the rATG dose was increased for Patients 2 and 3 to 4 mg/kg IV for 3 doses starting on day −10. b) Fludarabine: Cumulative AUC (cAUC) for Patient 1 was within the previously published goal and the same dosing of 35 mg/m2 IV for 4 doses was maintained for Patients 2 and 3.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Blood Count at Screening and Recovery Post αβdepleted-HSCT.

All patients were monitored post-HSCT with donor engraftment that enabled rapid tri-lineage blood count recovery in each patient (n = 3). Patient 2 developed immune mediated hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia after HSCT that resolved post treatment.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Immune Subsets at Screening and Recovery Post αβdepleted-HSCT.

All patients were monitored post-HSCT with immune recovery similar to previous reports with this type of donor graft (n = 3). Decreased CD19+ B-cells occurred in patient 2 at 24 weeks post-HSCT due to treatment for immune mediated hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Bone Marrow Hematopoiesis at Screening and Recovery with Restored Hematopoiesis and DNA-Damage Resistance Post αβdepleted-HSCT.

a) Minimal in vitro colony forming counts (CFCs) at screening (red) indicative of reduced HSPC activity due to BMF in each individual with FA pre-treatment compared to healthy adult and pediatric controls (black) with increased CFC activity post allo-HSCT in all patients assessed (grey, gold and teal). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Each bar represents an independent sample, with values averaged from three technical replicates. b) No mitomycin C (MMC)-resistance was observed in BM cells on research testing at patient enrollment in each of the treated individuals, indicative of FA disease with no somatic mosaicism at screening that subsequently increased post-HSCT with normalized 10 nM and 50 nM MMC-resistance in all patients due to engraftment of donor HSPCs without FA defects. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Each data point represents an independent sample, with values averaged from three technical replicates. Parametric unpaired t-test (two-tailed) was used for statistical analysis.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Agarwal, R., Bertaina, A., Soco, C. et al. Irradiation- and busulfan-free stem cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia using an anti-CD117 antibody: a phase 1b trial. Nat Med 31, 3183–3190 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03817-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03817-1