Abstract

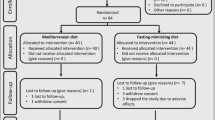

In healthy individuals, short cycles of a fasting-mimicking diet (FMD) decrease systemic inflammatory markers and improve metabolic health. Potential benefits of FMD have not been investigated in Crohn’s disease (CD). We conducted an open-label, randomized, controlled trial to assess the effects of FMD in adults with mild-to-moderate CD. Patients in the FMD group followed an FMD for five consecutive days per month for three consecutive months, returning to their regular baseline diet on non-FMD days. Control participants continued their baseline diet. The primary outcome of clinical response was a reduction in CD Activity Index (CDAI) of at least 70 points or CDAI of ≤150 after the third 5-day diet cycle. Forty-five patients in the FMD group (69.2%) and 14 patients in the control group (43.8%) met the primary outcome of clinical response (P = 0.03). Forty-two patients in the FMD group (64.6%) and 12 patients in the control group (37.5%) achieved the secondary outcome of clinical remission (P = 0.02). There was also a decline from baseline in fecal calprotectin (an inflammatory marker) in the FMD group compared with the control group (−22.0% versus 8.0%, P = 0.03). Exploratory analyses of plasma metabolites and peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression revealed post-FMD decreases in key inflammatory lipid mediators and immune-effector transcripts, concordant with reduced CD activity. Together, these findings demonstrate that FMD is superior to a baseline diet for inducing clinical response, clinical remission and biochemical improvement in mild-to-moderate CD, and support further investigation of FMD as an adjunctive therapy for chronic inflammatory diseases. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04147585.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

We have deposited metabolomics raw data on figshare (https://figshare.com/s/5ef87ff3127d0aad5a5a). Anonymized clinical data may be made available upon reasonable request with at least 4 weeks’ notice. Data access requests should contact the corresponding author. Approval of such requests is at the PI’s and sponsor’s discretion and depends on the nature of the request, the merit of the research proposed, the availability of the data and the intended use of the data.

References

Wang, R., Li, Z., Liu, S. & Zhang, D. Global, regional and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open 13, e065186 (2023).

Elmasry, S. & Ha, C. Evidence-based approach to the management of mild Crohn’s disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 22, 480–483 (2024).

Lewis, J. D. & Abreu, M. T. Diet as a trigger or therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 152, 398–414 (2017).

Gubatan, J. et al. Dietary exposures and interventions in inflammatory bowel disease: current evidence and emerging concepts. Nutrients 15, 579 (2023).

Lewis, J. D. et al. A randomized trial comparing the specific carbohydrate diet to a Mediterranean diet in adults with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 161, 837–852 (2021).

Johnston, B. C. et al. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA 312, 923–933 (2014).

Dansinger, M. L., Gleason, J. A., Griffith, J. L., Selker, H. P. & Schaefer, E. J. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone Diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA 293, 43–53 (2005).

Wei, M. et al. Fasting-mimicking diet and markers/risk factors for aging, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaai8700 (2017).

De Groot, S. et al. Fasting mimicking diet as an adjunct to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer in the multicentre randomized phase 2 DIRECT trial. Nat. Commun. 11, 3083 (2020).

Rangan, P. et al. Fasting-mimicking diet modulates microbiota and promotes intestinal regeneration to reduce inflammatory bowel disease pathology. Cell Rep. 26, 2704–2719 (2019).

Damas, O. M. et al. A pilot randomized control trial to assess the adjunctive effect of diet on response to advanced therapies in patients with UC. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 23, 2579–2587 (2025).

Silverberg, M. S. et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 19, A:5A–A:36A (2005).

D’Haens, G. et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet 399, 2015–2030 (2022).

Ananthakrishnan, A. N. et al. AGA clinical practice guideline on the role of biomarkers for the management of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 165, 1367–1399 (2023).

Irvine, E. J., Zhou, Q. & Thompson, A. K. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT investigators. Canadian Crohn’s relapse prevention trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 91, 1571–1578 (1996).

Roseira, J., Sousa, H. T., Marreiros, A., Contente, L. F. & Magro, F. Short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: translation and validation to the Portuguese language. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 19, 59 (2021).

Panaccione, R. et al. Achievement of endoscopic remission after induction reduces hospitalization burden in Crohn’s disease: findings from a pooled post hoc analysis of risankizumab and upadacitinib phase III trials. J. Crohns Colitis 19, jjae128 (2025).

Sharon, P. & Stenson, W. F. Enhanced synthesis of leukotriene B4 by colonic mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 86, 453–460 (1984).

Kikut, J. et al. Involvement of proinflammatory arachidonic acid (ARA) derivatives in Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). J. Clin. Med. 11, 1861 (2022).

Szczuko, M., Komisarska, P., Kikut, J., Drozd, A. & Sochaczewska, D. Calprotectin is associated with HETE and HODE acids in inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Clin. Med. 12, 7584 (2023).

Faizo, N., Narasimhulu, C. A., Forsman, A., Yooseph, S. & Parthasarathy, S. Peroxidized linoleic acid, 13-HPODE, alters gene expression profile in intestinal epithelial cells. Foods 10, 314 (2021).

Henderson, W. R. Jr The role of leukotrienes in inflammation. Ann. Intern. Med. 121, 684–697 (1994).

Stanke-Labesque, F., Pofelski, J., Moreau-Gaudry, A., Bessard, G. & Bonaz, B. Urinary leukotriene E4 excretion: a biomarker of inflammatory bowel disease activity. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 14, 769–774 (2008).

Paruchuri, S. et al. Leukotriene E4-induced pulmonary inflammation is mediated by the P2Y12 receptor. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2543–2555 (2009).

Ikehata, A. et al. Altered leukotriene B4 metabolism in colonic mucosa with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 30, 44–49 (1995).

Afonso, P. V. et al. LTB4 is a signal relay molecule during neutrophil chemotaxis. Dev. Cell 22, 1079–1091 (2012).

Diab, J. et al. A quantitative analysis of colonic mucosal oxylipins and endocannabinoids in treatment-naive and deep remission ulcerative colitis patients and the potential link with cytokine gene expression. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25, 490–497 (2019).

Ben-Mustapha, Y. et al. Altered mucosal and plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids, oxylipins, and endocannabinoids profiles in Crohn’s disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 168, 106741 (2023).

Koudelka, A. et al. Lipoxin A4 yields an electrophilic 15-oxo metabolite that mediates FPR2 receptor-independent anti-inflammatory signaling. J. Lipid Res. 66, 100705 (2024).

McGuffee, R. M., Luetzen, M. A. & Ford, D. A. Resolving lipoxin A4: endogenous mediator or exogenous anti-inflammatory agent? J. Lipid Res. 66, 100734 (2024).

Finnell, J. S., Saul, B. C., Goldhamer, A. C. & Myers, T. R. Is fasting safe? A chart review of adverse events during medically supervised, water-only fasting. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 18, 67 (2018).

Turner, D. et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the international organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 160, 1570–1583 (2021).

Sollelis, E. et al. Combined evaluation of biomarkers as predictor of maintained remission in Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 25, 2354–2364 (2019).

Zubin, G. & Peter, L. Predicting endoscopic Crohn’s disease activity before and after induction therapy in children: a comprehensive assessment of PCDAI, CRP, and fecal calprotectin. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21, 1386–1391 (2015).

Markó, L. et al. Tubular epithelial NF-κB activity regulates ischemic AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 2658–2669 (2016).

Traba, J. et al. Fasting and refeeding differentially regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human subjects. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 4592–4600 (2015).

Rutgeerts, P. et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease: data from the EXTEND trial. Gastroenterology 142, 1102–1111 (2012).

Schmitt, H. et al. Expansion of IL-23 receptor bearing TNFR2+ T cells is associated with molecular resistance to anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease. Gut 68, 814–828 (2019).

Koelink, P. J. et al. Anti-TNF therapy in IBD exerts its therapeutic effect through macrophage IL-10 signalling. Gut 69, 1053–1063 (2020).

Rutgeerts, P. et al. Scheduled maintenance treatment with infliximab is superior to episodic treatment for the healing of mucosal ulceration associated with Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. 63, 433–442 (2006).

Swanson, K. V., Deng, M. & Ting, J. P.-Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 477–489 (2019).

Schroder, K. & Tschopp, J. The inflammasomes. Cell 140, 821–832 (2010).

Mao, L., Kitani, A., Strober, W. & Fuss, I. J. The role of NLRP3 and IL-1β in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Immunol. 9, 2566 (2018).

Ducarmon, Q. R. et al. Remodelling of the intestinal ecosystem during caloric restriction and fasting. Trends Microbiol. 31, 832–844 (2023).

Damaskos, D. & Kolios, G. Probiotics and prebiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: microflora ‘on the scope’. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 65, 453–467 (2008).

Shabkhizan, R. et al. The beneficial and adverse effects of autophagic response to caloric restriction and fasting. Adv. Nutr. 14, 1211–1225 (2023).

Brandhorst, S. et al. A periodic diet that mimics fasting promotes multi-system regeneration, enhanced cognitive performance and healthspan. Cell Metab. 22, 86–99 (2015).

Huang, C. et al. Ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate ameliorates colitis by promoting M2 macrophage polarization through the STAT6-dependent signaling pathway. BMC Med. 20, 148 (2022).

Newman, J. C. & Verdin, E. β-Hydroxybutyrate. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 37, 51–76 (2017).

Martinez-Lopez, N. et al. System-wide benefits of intermeal fasting by autophagy. Cell Metab. 26, 856–871 (2017).

Rutgeerts, P. et al. Effect of faecal stream diversion on recurrence of Crohn’s disease in the neoterminal ileum. Lancet 338, 771–774 (1991).

Filardy, A. A., Ferreira, J. R. M., Rezende, R. M., Kelsall, B. L. & Oliveira, R. P. The intestinal microenvironment shapes macrophage and dendritic cell identity and function. Immunol. Lett. 253, 41–53 (2023).

Mowat, A. M. & Agace, W. W. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 667–685 (2014).

Narula, N. et al. Defining endoscopic remission in Crohn’s disease: MM-SES-CD and SES-CD thresholds associated with low risk of disease progression. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 22, 1687–1696 (2024).

Marsh, A. et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of an anti-inflammatory dietary pattern on disease activity, symptoms and microbiota profile in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 78, 1072–1081 (2024).

Bodini, G. et al. A randomized, 6-wk trial of a low FODMAP diet in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrition 67–68, 110542 (2019).

Cox, S. R. et al. Effects of low FODMAP diet on symptoms, fecal microbiome, and markers of inflammation in patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology 158, 176–188 (2020).

Lomer, M. C. E. et al. Lack of efficacy of a reduced microparticle diet in a multi-centred trial of patients with active Crohn’s disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 377–384 (2005).

Lomer, M. C., Harvey, R. S., Evans, S. M., Thompson, R. P. & Powell, J. J. Efficacy and tolerability of a low microparticle diet in a double blind, randomized, pilot study in Crohn’s disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 101–106 (2001).

De Sire, R. et al. Exclusive enteral nutrition in adult Crohn’s disease: an overview of clinical practice and perceived barriers. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 14, 493–501 (2021).

Mehta, P., Pan, Z., Furuta, G. T., Kim, D. Y. & de Zoeten, E. F. Parent perspectives on exclusive enteral nutrition for the treatment of pediatric Crohn disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 71, 744–748 (2020).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0. dctd.cancer.gov/research/ctep-trials/for-sites/adverse-events/ctcae-v5-5x7.pdf (2017).

Thia, K. T. et al. Defining the optimal response criteria for the Crohn’s disease activity index for induction studies in patients with mildly to moderately active Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 3123–3131 (2008).

Sands, B. E. et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 876–885 (2004).

Benjamini, Y., Krieger, A. M. & Yekutieli, D. Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika 93, 491–507 (2006).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Psychology Press, 2009).

Austin, P. C. & Stuart, E. A. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat. Med. 34, 3661–3679 (2015).

Rubin, S. J. S. et al. Mass cytometry reveals systemic and local immune signatures that distinguish inflammatory bowel diseases. Nat. Commun. 10, 2686 (2019).

Souza, A. L. & Patti, G. J. A protocol for untargeted metabolomic analysis: from sample preparation to data processing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2276, 357–382 (2021).

Cajka, T. et al. Optimization of mobile phase modifiers for fast LC–MS-based untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1987 (2023).

Danlos, F.-X. et al. Metabolomic analyses of COVID-19 patients unravel stage-dependent and prognostic biomarkers. Cell Death Dis. 12, 258 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust to Stanford University (to S.R.S., C.G., J.L.S. and A.H.). We specifically acknowledge Helmsley’s S. Soni for her overall support. Additional funding support was provided by NIH–NCATS–CTSA (grant UM1TR004921 to S.R.S. and J.Y.), the Plant Based Diet Initiative at Stanford University (to C.K. and S.R.S.), Kenneth Rainin Foundation (to S.R.S., J.L.S. and S.P.S.), the Doris Duke Foundation Physician Scientist Fellowship Award (2021091 to J.G.), CZ Biohub Physician-Scientist Scholar Award (to J.G.), NIH-NIDDK LRP Award (2L30 DK126220 to J.G., NIH-T32DK007056 to S.P.S. and NIH-K08DK134856 to S.P.S.), Colleen and Robert D. Hass Fund (to S.P.S.), UCSF Center for the Rheumatic Diseases (to J.F.A.), Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation (to J.F.A.), Arthritis Research Coalition (to J.F.A.), Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Investigator Program (to J.L.S.) and NIH-NIDDK (R01DK085025 to J.L.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R.S. conceptualized the study and acquired funding. S.R.S., C.G., A.H., J.L.S., J.F.A., V.D.L., D.P., L.B., M.M.D., V.C., J.Y., T.F., C.K. and K.J. developed the methodology. C.K., T.F., J.Y., K.J., E.D., H.J., S.R.S. and V.C. performed the formal analysis and visualization. T.F., C.K., K.J., K.K., S. Streett, E.H., G.B., S. Singh, D.L., N.A., J.G., E.D., H.J., M.T., A.P., Y.J., L.B., S.P.S., D.M., S.R.S. and D.P. helped with patient recruitment and data collection. T.F., C.K., J.Y., E.D., H.J., M.T. and K.J. conducted data curation. S.R.S., A.H., J.L.S., M.M.D. and C.G. were responsible for supervision. C.K., T.F. and S.R.S. contributed to writing the original draft of the paper. All authors were involved in writing, reviewing and editing the paper, and provided the final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

V.D.L. has equity interest in L-Nutra and has filed patents related to the FMD. V.D.L. does not receive consulting fees from L-Nutra and has committed his shares of the company to charitable organizations. The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Qiwei Li, Nicholas Powell and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ashley Castellanos-Jankiewicz, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Clinical outcomes after the first FMD cycle.

CDAI score significantly decreased among participants with mild-to-moderately active CD after completing the first cycle of the FMD compared to control. a, After completing the first 5-day FMD, more participants achieved clinical remission compared to participants who made no diet changes (60.0% versus 37.5%, P = 0.04). b,c, This difference in clinical response after a single cycle of FMD was also observed when patients were stratified into mild (b, 75.0% versus 43.5%, P = 0.02) and moderate (c, 47.6% versus 0.0%, P = 0.01) disease. Results are shown as percentages of participants meeting the criteria for response. P values were calculated by Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test; NS: P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05. FMD, fasting-mimicking diet.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Clinical outcomes 3 months after the third FMD cycle.

CDAI score assessment at the end of the study (week 24); for participants in the FMD group, this corresponded to approximately 3 months after completion of the third FMD cycle. a–d, No significant differences were observed in the percentages of participants achieving clinical response (a, 56.9% versus 53.1%, P = 0.83) or clinical remission (b, 55.4% versus 43.8%, P = 0.39) between FMD and control groups after 3-month washout, regardless of mild (c, 54.6% versus 60.9%, P = 0.79) or moderate (d, 71.4% versus 33.3%, P = 0.10) disease severity. Results are shown as percentages of participants meeting the criteria for response. P values were calculated by Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test; NS: P ≥ 0.05. FMD, fasting-mimicking diet.

Extended Data Fig. 3 PRO and quality of life after the third FMD cycle.

a, Remission by PRO was achieved by 47.7% of FMD versus 25.0% (P < 0.05). b, Improvement in SIBDQ by more than 50 points was observed in 46.2% of FMD versus 25.0% of control participants (P < 0.05)15,16. c, Remission by PGA was observed in 24.6% of FMD versus 6.3% of control participants (P = 0.03). FMD, fasting-mimicking diet; PRO, patient-reported outcomes; SIBDQ, short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire; PGA, patient global assessment. Results are shown as percentages of participants meeting the criteria for response. P values were calculated by two-sided Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test; *P < 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Per-protocol analysis of clinical, patient-reported, and laboratory outcomes after the third FMD cycle.

Data from participants who completed the study were assessed after the third FMD cycle; for participants in the control group, this corresponded to approximately 12 weeks after baseline. a–c, Significantly more participants met criteria for clinical response 70 (a, 82.0% versus 50.0%, P < 0.01), clinical response 100 (b, 78.0% versus 42.9%, P < 0.01), and clinical remission (c, 76.0% versus 39.3%, P < 0.01) after completing the three FMD cycles compared to participants who made no dietary changes. d,e, Compared to baseline, a significantly higher percentage of participants reported remission by PRO (d, 58.0% versus 25.0%, P < 0.01) and improvement in SIBDQ score (e, 56.0% versus 28.6%, P = 0.02) after the third FMD cycle compared to participants in the control arm. f,g, There were significant differences in mean percentage change in CRP (f, −15.7% versus 36.9%, P < 0.01) and fecal calprotectin (g, −36.5% versus 8.9%, P < 0.01) between the FMD and control arms. a–e, Percentages of participants meeting the criteria for response. f,g, Mean percentage change measured from baseline to after the third FMD cycle; error bars represent standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). P values were calculated by Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test (a–e) or t-test (f,g); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. FMD, fasting-mimicking diet; PRO, patient-reported outcomes; SIBDQ, short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Downregulated pathways in FMD compared to control.

Features with fold change ≤1/1.5 (FMD versus control) underwent pathway enrichment analysis using Reactome in MetaboAnalyst. Figure shows the top 20 downregulated pathways. Two-sided tests as implemented in MetaboAnalyst; P values were FDR-adjusted using the two-stage Benjamini-Krieger-Yekutieli (BKY) procedure, with significance defined as q ≤ 0.10. All pathways shown have FDR-adjusted P < 0.10. Dot size indicates the enrichment score, and the x-axis represents statistical significance as −log₁₀(FDR). FMD, fasting-mimicking diet; RAMD, random accelerator molecular dynamics; FDR, false discovery rate; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κ B; AP-1, activator protein 1; PG, prostaglandins; TX, thromboxanes; LOX, lipooxygenases; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–7 and Note (CONSORT checklist, study protocol, statistical analysis plan and informed consent form (blank copy)).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kulkarni, C., Fardeen, T., Gubatan, J. et al. A fasting-mimicking diet in patients with mild-to-moderate Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Nat Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04173-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04173-w