Abstract

Disorder and flexibility in protein structures are essential for biological function but can also contribute to diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders. However, characterizing protein folding on a proteome-wide scale within biological matrices remains challenging. Here we present a method using a bifunctional chemical probe, named TME, to capture in situ, enrich and quantify endogenous protein disorder in cells. TME exhibits a fluorescence turn-on effect upon selective conjugation with proteins with free cysteines in surface-exposed and flexible environments—a distinctive signature of protein disorder. Using an affinity-based proteomic approach, we identify both basal disordered proteins and those whose folding status changes under stress, with coverage to proteins even of low abundance. In lymphoblastoid cells from individuals with Parkinson’s disease and healthy controls, our TME-based strategy distinguishes the two groups more effectively than lysate profiling methods. High-throughput TME fluorescence and proteomics further reveal a universal cellular quality-control mechanism in which cells adapt to proteostatic stress by adopting aggregation-prone distributions and sequestering disordered proteins, as illustrated in Huntington’s disease cell models.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under deposition numbers 2369832 for TME and 2369833 for 4-E. These data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif/.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE49 partner repository under dataset identifier PXD048735.

For proteomic data analysis, mass spectra were searched against the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database for Homo sapiens (organism ID: 9606) and Mus musculus (organism ID: 10090). For protein abundance quantification, the following databases were used as references: a previously reported deep proteomic analysis of Neuro-2a cells (PMCID: PMC4256493), M. musculus—whole organism (integrated; coverage: 90%; https://pax-db.org/dataset/10090/3224231993/), M. musculus—brain (integrated; coverage: 51%; https://pax-db.org/dataset/10090/961549256/), H. sapiens—whole organism (integrated; coverage: 99%; https://pax-db.org/dataset/9606/3902734007/) and H. sapiens—lymph node (integrated; coverage: 53%; https://pax-db.org/dataset/9606/952965544/). For cysteine functional annotation and cellular localization analysis, the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot Protein Knowledgebase release 2022_03, downloaded on 1 September 2022, was used. For PPI analysis, data were obtained from the R package ‘STRINGdb’, version 11, with a score threshold of 600. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom R scripts for analyzing proteomics and flow cytometry data are available at GitHub via https://github.com/shouxiang/Supp_TME_HongLab and Zenodo via https://zenodo.org/records/13922443 (ref. 50).

References

Hipp, M. S., Kasturi, P. & Hartl, F. U. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 421–435 (2019).

Perdigão, N. et al. Unexpected features of the dark proteome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15898–15903 (2015).

Deiana, A., Forcelloni, S., Porrello, A. & Giansanti, A. Intrinsically disordered proteins and structured proteins with intrinsically disordered regions have different functional roles in the cell. PLoS ONE 14, e0217889 (2019).

Coskuner-Weber, O., Mirzanli, O. & Uversky, V. N. Intrinsically disordered proteins and proteins with intrinsically disordered regions in neurodegenerative diseases. Biophys. Rev. 14, 679–707 (2022).

Hirose, T., Ninomiya, K., Nakagawa, S. & Yamazaki, T. A guide to membraneless organelles and their various roles in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 288–304 (2023).

Chiti, F. & Dobson, C. M. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of progress over the last decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 27–68 (2017).

Uversky, V. N., Oldfield, C. J. & Dunker, A. K. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 37, 215–246 (2008).

Zhang, S., Greening, D. W. & Hong, Y. Recent advances in bioanalytical methods to measure proteome stability in cells. Analyst 146, 2097–2109 (2021).

Theillet, F. -X. In-cell structural biology by NMR: the benefits of the atomic scale. Chem. Rev. 122, 9497–9570 (2022).

Feng, Y. et al. Global analysis of protein structural changes in complex proteomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1036–1044 (2014).

Malinovska, L. et al. Proteome-wide structural changes measured with limited proteolysis-mass spectrometry: an advanced protocol for high-throughput applications. Nat. Protoc. 18, 659–682 (2023).

Habchi, J., Tompa, P., Longhi, S. & Uversky, V. N. Introducing protein intrinsic disorder. Chem. Rev. 114, 6561–6588 (2014).

Kulkarni, P. et al. Intrinsically disordered proteins: critical components of the wetware. Chem. Rev. 122, 6614–6633 (2022).

Hong, Y., Lam, J. W. & Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 5361–5388 (2011).

Chen, M. Z. et al. A thiol probe for measuring unfolded protein load and proteostasis in cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 474 (2017).

Zhang, S. et al. A maleimide-functionalized tetraphenylethene for measuring and imaging unfolded proteins in cells. Chem. Asian J. 14, 904–909 (2019).

Owyong, T. C. et al. A molecular chameleon for mapping subcellular polarity in an unfolded proteome environment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 10129–10135 (2020).

Sabouri, S. et al. Construction of a highly sensitive thiol-reactive aiegen-peptide conjugate for monitoring protein unfolding and aggregation in cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2101300 (2021).

Milo, R. What is the total number of protein molecules per cell volume? A call to rethink some published values. Bioessays 35, 1050–1055 (2013).

Wang, G. et al. A buried water network modulates the activity of the Escherichia coli disulphide catalyst DsbA. Antioxidants 12, 380 (2023).

Weerapana, E. et al. Quantitative reactivity profiling predicts functional cysteines in proteomes. Nature 468, 790–795 (2010).

Oldfield, C. J. & Dunker, A. K. Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 553–584 (2014).

Hentze, M. W., Castello, A., Schwarzl, T. & Preiss, T. A brave new world of RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 327–341 (2018).

van der Lee, R. et al. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem. Rev. 114, 6589–6631 (2014).

Wright, P. E. & Dyson, H. J. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 18–29 (2015).

Mészáros, B., Erdős, G. & Dosztányi, Z. IUPred2A: context-dependent prediction of protein disorder as a function of redox state and protein binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W329–W337 (2018).

Uversky, V. N. Analyzing IDPs in interactomes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2141, 895–945 (2020).

Yu, H., Kim, P. M., Sprecher, E., Trifonov, V. & Gerstein, M. The importance of bottlenecks in protein networks: correlation with gene essentiality and expression dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e59 (2007).

Davies, S. W. et al. Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation. Cell 90, 537–548 (1997).

Ramdzan, Y. M. et al. Tracking protein aggregation and mislocalization in cells with flow cytometry. Nat. Methods 9, 467–470 (2012).

Scherzinger, E. et al. Self-assembly of polyglutamine-containing huntingtin fragments into amyloid-like fibrils: Implications for Huntington’s disease pathology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 4604–4609 (1999).

Arrasate, M., Mitra, S., Schweitzer, E. S., Segal, M. R. & Finkbeiner, S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature 431, 805–810 (2004).

Johnston, J. A., Ward, C. L. & Kopito, R. R. Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1883–1898 (1998).

Kaganovich, D., Kopito, R. & Frydman, J. Misfolded proteins partition between two distinct quality control compartments. Nature 454, 1088–1095 (2008).

Wear, M. P. et al. Proteins with intrinsically disordered domains are preferentially recruited to polyglutamine aggregates. PLoS ONE 10, e0136362 (2015).

Ramdzan, Y. M. et al. Huntingtin inclusions trigger cellular quiescence, deactivate apoptosis, and lead to delayed necrosis. Cell Rep. 19, 919–927 (2017).

Tan, C. S. H. et al. Thermal proximity coaggregation for system-wide profiling of protein complex dynamics in cells. Science 359, 1170–1177 (2018).

Ross, J. L. The dark matter of biology. Biophys. J. 111, 909–916 (2016).

Mackmull, M. -T. et al. Global, in situ analysis of the structural proteome in individuals with Parkinson’s disease to identify a new class of biomarker. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 29, 978–989 (2022).

D’Alfonso, L., Collini, M. & Baldini, G. Does β-lactoglobulin denaturation occur via an intermediate state? Biochemistry 41, 326–333 (2002).

Zhou, J. et al. Gel absorption-based sample preparation for the analysis of membrane proteome by mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 404, 204–210 (2010).

Rappsilber, J., Mann, M. & Ishihama, Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1896–1906 (2007).

Tyanova, S., Temu, T. & Cox, J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 11, 2301–2319 (2016).

Rieckmann, J. C. et al. Social network architecture of human immune cells unveiled by quantitative proteomics. Nat. Immunol. 18, 583–593 (2017).

Hornburg, D. et al. Deep proteomic evaluation of primary and cell line motoneuron disease models delineates major differences in neuronal characteristics. Mol. Cell Proteom. 13, 3410–3420 (2014).

Yu, G., Wang, L. -G., Han, Y. & He, Q. -Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Yu, G. & He, Q. -Y. ReactomePA: an R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. Mol. Biosyst. 12, 477–479 (2016).

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849 (2016).

Perez-Riverol, Y. et al. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D543–d552 (2022).

Zhang, X. shouxiang/Supp_TME_HongLab: R scripts for paper "Global analysis of endogenous protein disorder in cells" (v1.0.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13922443 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants to Y.H. from the Australian Research Council (FT210100271 and DE170100058), the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1161803 and APP2029017) and the Rebecca L. Cooper Medical Research Foundation (PG2018043). S.Z. was supported by a La Trobe University Graduate Research Scholarship, a La Trobe University Full Fee Research Scholarship and an LIMS Writing-up Award. We thank the Bio21 Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility and La Trobe University Bioimaging and Comprehensive Proteomics Platform for the professional support and access to the equipment. We thank the assistance of resources and services from the National Computational Infrastructure by the Australian government. This research was undertaken in part using the MX1 beamline and MX2 beamline (using the Australian Cancer Research Foundation detector) at the Australian Synchrotron, part of ANSTO. We are grateful to D. Loesch (La Trobe University), A. Atkinson (La Trobe University), A. Evans (Royal Melbourne Hospital) and E. Storey (Monash University/Alfred Hospital) for assistance with clinical information and original participant recruitment. We also thank D. M. Hatters (University of Melbourne), M. Lee (La Trobe University), T. Pukala (University of Adelaide), M.-C. Giel (La Trobe University) and R. Xu (La Trobe University) for helping with sample preparation, sharing original plasmids and helpful discussions, and C. Allan (La Trobe University) for isolation of the original lymphoblastoid cell lines.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. conceived and supervised the project. S.Z. designed and performed the biological experiments, analyzed data and prepared the figures; T.C.O. performed the chemical synthesis and photophysical characterizations, analyzed data and prepared the figures; O.S. prepared and maintained lymphoblast cells; X.S. provided technical support and discussion to experiments related to HD models; G.W. and B.H. provided recombinant DsbA proteins and contributed to data interpretation; L.E. and A.V. conducted the western blotting validation experiments and analysis; D.W.G. and N.A.W. provided technical support of protein mass spectrometry experiments; J.M.W. contributed to single-crystal X-ray crystallography experiments and analysis; W.W.H.W. contributed to probe synthesis; P.R.F. sourced and managed the patient and healthy donor cell lines and was involved in the related experimental design and data interpretation; S.Z., T.C.O. and Y.H. wrote the paper with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.H., S.Z. and T.C.O. have filed a patent application covering the work presented. The other authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Methods thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Arunima Singh, in collaboration with the Nature Methods team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Crystal structure and photophysical characterization of TME.

a, Crystal structures of thiol reactive TME and its isomer 4-E. b, DFT calculations for TME and its thiol adduct TME-S showing a loss of the LUMO energy level from the maleimide and the photoinduced electron transfer effect upon reaction with thiol. c-d, Changes of TME-S fluorescence intensity in solvent mixture of ethylene glycol: glycerol with increase of glycerol fraction (vol%) demonstrating restriction of intramolecular motion (RIM) effect arising from viscosity increase (c) and in water: DMSO with increase of water fraction (vol%) demonstrating the RIM effect arising from aggregation (d). Concentration of TME: 10 µM; excitation wavelength: 322 nm; emission wavelength: 475 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 TME fluorescence reveals protein unfolding in vitro.

a, End-point emission spectra of samples in Fig. 2a. b, Fluorescence of TME with unfolded BLG in the presence of 0.025 – 8 mM GSH. Arrow indicates intracellular protein to glutathione thiol ratio, that is, 7:3. n = 4 biological replicates; mean ± s.d. c-d, TME fluorescence measured by the plate reader in Fig. 2d and e. Sample solutions were aliquoted from the in-gel fluorescence samples. n = 4 technical replicates; mean ± s.d. Results were consistent with kinetic curves (Fig. 2a and c).

Extended Data Fig. 3 TME biocompatibility and its functionality to enrich unfolded proteins in vitro and cellular proteins from cell lysate via RUBICON workflow.

a, Cell viability assays for cells stained with 25 – 75 µM TME for 30 and 60 min. Cells were also incubated with the same amount of DMSO as vehicle controls. n = 4 biological replicates; mean ± s.d. b, Confocal microscopy images of cells stained with TME and co-stained with ER-Tracker and DRAQ5 for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and nucleus respectively. Scale bar: 20 µm. c-d, Only TME labeled model proteins (c) and proteins from cell lysates (d) were enriched by the RUBICON workflow, which displayed evident fluorescence in TME, SYPRO Ruby and Coomassie Blue channels. The input loading amount for BLG and cell lysate was 7.5 and 50 µg respectively. SYPRO Ruby were used as a sensitive stain to visualize all proteins while Coomassie Blue were used to quantify total protein amount. “TME-/BLG-” and “TME-/Lysate-” denote samples that contained beads only. e, Flow cytometry results showing that proteostatic stressor (that is, tunicamycin and MG132) treated cells displayed significantly higher TME fluorescence compared to control. Gating strategies are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. n = 3 biological replicates; mean ± s.d.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterization of TME binders in the tunicamycin dataset.

a, Strategies to interpret proteomics results. In each dataset, there were four experimental conditions: TME-/Drug-, TME + /Drug-, TME-/Drug + , TME + /Drug + . Each experimental condition was processed parallelly with the RUBICON workflow. Note that unlabeled proteins can be potentially enriched by Dynabeads, that is, non-specific binders. Comparison of TME-/Drug- and TME + /Drug- identified TME binders in control condition, for example, Fig. 3a. Comparison of TME-/Drug+ and TME + /Drug+ identified TME binders in drug treated conditions, for example, Fig. 3b. Comparison of TME + /Drug- and TME + /Drug+ identified proteins with higher abundance upon drug treatment using RUBICON, for example, Fig. 3c. Among these proteins, the TME labeled ones were proteins that became more disordered in stressed conditions. They were identified as the intersections of significant hits in Fig. 3b and c, for example, and labeled with their gene name. Created with BioRender.com. b, Western Blot results for validation of proteins enriched from untreated or tunicamycin treated cells with or without TME using the RUBICON workflow. c, The number of proteins (protein counts) detected in TME labeled/unlabeled, and tunicamycin treated/untreated cells, shown on the top of each bar plot. Protein counts in each condition were calculated as the number of proteins detected in all triplicates. For this calculation, mass spectra were searched using MaxQuant without ‘Match between runs’. d, TME binders in Fig. 3a and b were enriched in intracellular proteins (for example, nucleus, cytoplasm, ER). On top of each bar shows the fold enrichment, followed by the significance level. P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test; ‘ns’, no significance; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. e, Enrichment analysis of TME binders in Fig. 3b. “Tunicamycin binders” refer to TME binders in tunicamycin treated condition. P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test, and further adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg procedure as the multi-test adjustment method. f, Protein-protein interaction network of the six proteins that became more disordered upon tunicamycin treatment. Green nodes denote the first neighbor of these proteins.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Characterization of TME binders in the MG132 dataset.

a-c, TME binders in control (a) and MG132 treated (b) conditions. Proteins that became more disordered upon MG132 treatment were labeled with gene names (b and c). Data show n = 3 biological replicates; P value was calculated using the unpaired two-sample two-sided Student’s t-test assuming two variances are equal, and further adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg procedure as the multi-test adjustment method. Color represents log10(iBAQ) value. Red points denote proteins undetectable by the lysate profiling method. d, Venn diagram of TME binders in control and MG132 treated conditions. e, TME binders in Extended Data Figs. 5a and 5b were not heavily enriched in functional cysteines, indicating TME displayed a completely distinct reactivity towards cellular cysteines compared to the IA alkyne probe. On top of each bar shows the fold enrichment, followed by the significance level. f, TME binders in Extended Data Figs. 5a and 5b were enriched in intracellular proteins (for example, nucleus, cytoplasm, ER) but depleted in membrane and secreted proteins. On top of each bar shows the fold enrichment, followed by the significance level. e-f, P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test; ‘ns’, no significance; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. g-h, Enrichment analysis of TME binders in Extended Data Fig. 5a (g) and 5b (h). “MG132 binders” refer to TME binders in MG132 treated condition. P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test, and further adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg procedure as the multi-test adjustment method. i-k, IUPred2, ANCHOR2, degree and betweenness value of TME binders in Extended Data Fig. 5a and b were significantly higher than the proteome average. Data show n = 17120 for Proteome, 680 for Control, and 697 for MG132; P value was calculated using the unpaired two-sample two-sided Wilcoxon test; ****, P < 0.0001. The boxplot displays five key elements: the median, shown as the white circle at the center; the upper hinge, representing the third quartile (75th percentile); and the lower hinge, representing the first quartile (25th percentile). The upper whisker extends to the largest value within 1.5 * IQR (interquartile range) from the upper hinge, while the lower whisker extends to the smallest value within 1.5 * IQR from the lower hinge.

Extended Data Fig. 6 TME binders cover disordered proteins of low abundance.

a-c, Violin (left two panels) and bar (right two panels) plots for “Lysate,” “Binder,” and “Undetectable” in the MG132 dataset, using Neuro-2a cell line proteomic dataset (a), the PaxDb Brain (Integrated) dataset (b), and the PaxDb Whole Organism (Integrated) dataset (c) as standard references. Violin plots show the distribution of protein abundance (n = 2893 for Lysate, 680 for Control Binder, 107 for Control Undetectable, 697 for MG132 Binder, 88 for MG132 Undetectable, to be mapped to the corresponding reference dataset; P value was calculated using the unpaired two-sample two-sided Wilcoxon test; ****, P < 0.0001). The boxplot displays five key elements: the median, shown as the white circle at the center; the upper hinge, representing the third quartile (75th percentile); and the lower hinge, representing the first quartile (25th percentile). The upper whisker extends to the largest value within 1.5 * IQR (interquartile range) from the upper hinge, while the lower whisker extends to the smallest value within 1.5 * IQR from the lower hinge. Bar plots illustrate the percentages of proteins within each percentile, with percentiles determined by the respective standard references. ‘U’ in the last column of the bar plot denotes ‘Unmapped,’ referring to proteins not found in the corresponding standard references. “Lysate,” “Binder,” and “Undetectable” denote: proteins detected by lysate profiling methods, TME binders identified by RUBICON exclusive of undetectable proteins, and TME binders only detected by RUBICON but not by lysate profiling methods (red dots in Extended Data Fig. 5a-b), respectively. Notably, referencing the Cell Line dataset results in the most unmapped proteins, followed by the Brain dataset, which leaves some proteins unmapped. Using the Whole Organism dataset, nearly all protein abundances can then be mapped.

Extended Data Fig. 7 TME binders are enriched in IDPs but depleted in structured proteins.

Classification of identified proteins by protein disorder in the proteome, tunicamycin and MG132 datasets. a, Schematic diagram showing the classification of proteins into 5 types. Type 1: Structured proteins with less than 5% of residues having an IUPred2 score greater than 0.5. Type 2a-c: Proteins with IDRs, where the percentage of residues with an IUPred2 score greater than 0.5 is between 5% and 80%. Type 2a: Proteins with cysteines only located in the structured regions. Type 2b: Proteins with cysteines only located in the disordered regions. Type 2c: Proteins with cysteines located in both structured and disordered regions. Type 3: IDPs, where the percentage of residues with an IUPred2 score greater than 0.5 is greater than 80%. Non-cysteine containing proteins, if any, are discarded from analysis. The red circle denotes the cysteine. b-c, Classification of proteins in the tunicamycin dataset with threshold length of 15 (b) and 30 (c) amino acids in the continuous disordered sequences. d-e, Classification of proteins in the MG132 dataset with threshold length of 15 (d) and 30 (e) amino acids in the continuous disordered sequences. On top of each bar shows the fold enrichment, followed by the significance level. P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test; ‘ns’, no significance; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Characterization of TME binders in the PD and healthy control lymphoblast datasets.

a, TME binders in Fig. 4a and 4b were not heavily enriched in functional cysteines, indicating TME displayed a completely distinct reactivity towards cellular cysteines compared to the IA alkyne probe. On top of each bar shows the fold enrichment, followed by the significance level. b, TME binders in Fig. 4a and b were enriched in intracellular proteins (for example, nucleus, cytoplasm, ER). On top of each bar shows the fold enrichment, followed by the significance level. P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test; ‘ns’, no significance; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. c-d, Enrichment analysis of TME binders in Fig. 4a (c) and 4b (d). “Healthy binders” refer to TME binders in the healthy control group and “PD binders” refer to TME binders in the PD group. P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test, and further adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg procedure as the multi-test adjustment method. e-g, IUPred2, ANCHOR2, degree and betweenness value of TME binders in Fig. 4a and b were significantly higher than the proteome average. Data show n = 20383 for Proteome, 438 for Healthy, and 464 for PD; P value was calculated using the unpaired two-sample two-sided Wilcoxon test; ‘ns’, no significance; ****, P < 0.0001. The boxplot displays five key elements: the median, shown as the white circle at the center; the upper hinge, representing the third quartile (75th percentile); and the lower hinge, representing the first quartile (25th percentile). The upper whisker extends to the largest value within 1.5 * IQR (interquartile range) from the upper hinge, while the lower whisker extends to the smallest value within 1.5 * IQR from the lower hinge. h, Parallel comparison of scree plots of lysate profiling using cell lysate (left) and protein disorder profiling using RUBICON (right).

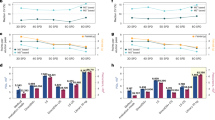

Extended Data Fig. 9 Supplementary data for the pulse shape analysis of Httex1.

a, Data of vehicle control, that is cells expressing mCherry only. Legends are the same as in Fig. 5. Data show n = 4 biological replicates; mean ± s.e.m.; P value was calculated using the unpaired two-sample two-sided Student’s t-test assuming two variances are equal; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. b, Flow cytometry results confirming negligible crosstalk between mCherry and TME fluorescence. Cytograms show mCherry.A versus TME fluorescence of monochromic cells, that is, cells either only stained with TME or only transfected with mCherry or mCherry-fused mHttex1. The shaded red, blue and pink areas denote stage I, II, and III, as defined in Fig. 5b, respectively. The rectangular gate denotes high TME signals, inside which shows the percentages of TME+ cells. c-d, Examples of separation of 97Q by H (c) and W (d) in the expression bin ranked 7, 17 and 25. Large and small values are referred to as top 25% and bottom 25% of H and W, respectively. In each expression bin, two-sample t-test was performed between TME signals from large and small H, and from large and small W.

Extended Data Fig. 10 46Q overexpression accelerates translation and triggers stress response and quality control.

a, Protein abundance of 46Q from Stage I to III in T, S and P fractions. b-c, Comparison of T-IIa and T-IIn, and S-IIa and S-IIn. Red dots denote proteins with higher abundance in IIa. d-f, Heatmap of cluster-A and cluster-D in T, S and P fraction (top); enrichment analysis of P/T/S-cluster-A (bottom). P value was calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test, and further adjusted by Benjamini-Hochberg procedure as the multi-test adjustment method.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion, Tables 1–3, Figs. 1–7 and Note.

Supplementary Video 1

Structural comparison between DsbA (wild type, in magenta) and DsbA (C33A mutant, in green).

Supplementary Data 1

Single-crystal data of compound TME.

Supplementary Data 2

Checkcif report of TME single crystal.

Supplementary Data 3

Single-crystal data of compound 4-E.

Supplementary Data 4

Checkcif report of 4-E single crystal.

Supplementary Data 5

List of commercial reagents used in this study.

Supplementary Data 6

Statistical source data of the exact P values of statistical analysis in this manuscript.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Original gel figures of in vitro fluorescence kinetics for Fig. 2d,e.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data for the tunicamycin dataset includes eight tabs: ‘ctrl_label_vs_unlabel’, ‘tuni_label_vs_unlabel’ and ‘label_tuni_vs_ctrl’ are the source data for Fig. 3a–c. ‘tuni_lysate’ provides the source data for lysate profiling. ‘ctrl_binder’ and ‘tuni_binder’ contain the source data for TME binders under control and tunicamycin-treated conditions. ‘ctrl_binder_enrichment’ and ‘tuni_binder_enrichment’ present the enrichment analysis results for ‘ctrl_binder’ and ‘tuni_binder’.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for the PD dataset includes eight tabs: ‘healthy_label_vs_unlabel’, ‘pd_label_vs_unlabel’ and ‘label_pd_vs_healthy’ are the source data for Fig. 4a–c. ‘pd_lysate’ provides the source data for lysate profiling. ‘healthy_binder’ and ‘pd_binder’ contain the source data for TME binders in healthy and PD group. ‘healthy_binder_enrichment’ and ‘pd_binder_enrichment’ present the enrichment analysis results for ‘healthy_binder’ and ‘pd_binder’.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data for the Htt dataset includes seven tabs: ‘pellet_heatmap’, ‘super_heatmap’ and ‘total_heatmap’ are the source data for P, S and T clustering. ‘pellet_2_volcano’ is the source data for Fig. 6c. ‘P-cluster-A_enrichment’, ‘S-cluster-A_enrichment’ and ‘T-cluster-A_enrichment’ are source data of the enrichment result of Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 10e,f.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Original gel figures for Extended Data Fig. 3c,d.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Original western blot results for Extended Data Fig. 4b.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data for the MG132 dataset includes eight tabs: ‘ctrl_label_vs_unlabel’, ‘mg_label_vs_unlabel’ and ‘label_mg_vs_ctrl’ are the source data for Extended Data Fig. 5a–c. ‘mg_lysate’ provides the source data for lysate profiling. ‘ctrl_binder’ and ‘mg_binder’ contain the source data for TME binders under control and MG132-treated conditions. ‘ctrl_binder_enrichment’ and ‘mg_binder_enrichment’ present the enrichment analysis results for ‘ctrl_binder’ and ‘mg_binder’.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Owyong, T.C., Sanislav, O. et al. Global analysis of endogenous protein disorder in cells. Nat Methods 22, 124–134 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02507-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02507-z

This article is cited by

-

Profiling the disordered proteome in cells using a chemical tag

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2025)