Abstract

Single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) has transformed biological imaging by enabling nanoscale visualization of intricate subcellular structures. However, conventional three-dimensional SMLM techniques typically exhibit lower axial resolution than lateral resolution, hindering isotropic investigations. Interferometric approaches, such as 4Pi-SMLM, enhance axial resolution by approximately fivefold through dual-objective coherent fluorescence detection, surpassing lateral resolution. Here we present 4Pi-SIMFLUX, which integrates structured illumination into 4Pi-SMLM to double its lateral resolution, achieving near-isotropic three-dimensional localization precision of 2–3 nm. We demonstrate that 4Pi-SIMFLUX breaks the 10-nm resolution barrier in biological samples, resolving microtubule ultrastructure and nuclear pore complexes with exceptional detail and clarity, while accounting for label size and localization density. Furthermore, it enables simultaneous multicolor imaging for interrogating multiple cellular components and high-fidelity, whole-cell visualization that captures comprehensive spatial organization. 4Pi-SIMFLUX effectively bridges the axial–lateral resolution gap, establishing a robust tool for molecular-scale imaging in complex cellular environments.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

An example dataset is available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30022948.v1 (ref. 50). Due to the extensive size of the raw data (>1 TB per cell, >50 TB in total), uploading it to an online repository is currently impractical. However, the datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

4Pi-SIMFLUX reconstruction code is available at https://github.com/zhanglab-srm/4Pi-SIMFLUX. The package is licensed under the GNU GPL.

References

Lelek, M. et al. Single-molecule localization microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 39 (2021).

Liu, S., Huh, H., Lee, S. H. & Huang, F. Three-dimensional single-molecule localization microscopy in whole-cell and tissue specimens. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 22, 155–184 (2020).

Huang, F. et al. Ultra-high resolution 3D imaging of whole cells. Cell 166, 1028–1040 (2016).

Aquino, D. et al. Two-color nanoscopy of three-dimensional volumes by 4Pi detection of stochastically switched fluorophores. Nat. Methods 8, 353–359 (2011).

Shtengel, G. et al. Interferometric fluorescent super-resolution microscopy resolves 3D cellular ultrastructure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3125–3130 (2009).

Bates, M. et al. Optimal precision and accuracy in 4Pi-STORM using dynamic spline PSF models. Nat. Methods 19, 603–612 (2022).

Gu, L. et al. Molecular-scale axial localization by repetitive optical selective exposure. Nat. Methods 18, 369–373 (2021).

Balzarotti, F. et al. Nanometer resolution imaging and tracking of fluorescent molecules with minimal photon fluxes. Science 355, 606–612 (2017).

Jouchet, P. et al. Nanometric axial localization of single fluorescent molecules with modulated excitation. Nat. Photonics 15, 297–304 (2021).

Cnossen, J. et al. Localization microscopy at doubled precision with patterned illumination. Nat. Methods 17, 59–63 (2020).

Reymond, L. et al. SIMPLE: structured illumination based point localization estimator with enhanced precision. Opt. Express 27, 24578–24590 (2019).

Gu, L. et al. Molecular resolution imaging by repetitive optical selective exposure. Nat. Methods 16, 1114–1118 (2019).

Huang, B., Wang, W., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Three-dimensional super-resolution imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. Science 319, 810–813 (2008).

Smith, C. S., Joseph, N., Rieger, B. & Lidke, K. A. Fast, single-molecule localization that achieves theoretically minimum uncertainty. Nat. Methods 7, 373–375 (2010).

Gotzke, H. et al. The ALFA-tag is a highly versatile tool for nanobody-based bioscience applications. Nat. Commun. 10, 4403 (2019).

Strauss, S. & Jungmann, R. Up to 100-fold speed-up and multiplexing in optimized DNA-PAINT. Nat. Methods 17, 789–791 (2020).

Dai, M., Jungmann, R. & Yin, P. Optical imaging of individual biomolecules in densely packed clusters. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 798–807 (2016).

Endesfelder, U., Malkusch, S., Fricke, F. & Heilemann, M. A simple method to estimate the average localization precision of a single-molecule localization microscopy experiment. Histochem. Cell Biol. 141, 629–638 (2014).

Nieuwenhuizen, R. P. et al. Measuring image resolution in optical nanoscopy. Nat. Methods 10, 557–562 (2013).

Thevathasan, J. V. et al. Nuclear pores as versatile reference standards for quantitative superresolution microscopy. Nat. Methods 16, 1045–1053 (2019).

Reinhardt, S. C. M. et al. Ångström-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Nature 617, 711–716 (2023).

Schuller, A. P. et al. The cellular environment shapes the nuclear pore complex architecture. Nature 598, 667–671 (2021).

Gwosch, K. C. et al. Reply to: assessment of 3D MINFLUX data for quantitative structural biology in cells. Nat. Methods 20, 52–54 (2023).

Heydarian, H. et al. 3D particle averaging and detection of macromolecular symmetry in localization microscopy. Nat. Commun. 12, 2847 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Universal inverse modeling of point spread functions for SMLM localization and microscope characterization. Nat. Methods 21, 1082–1093 (2024).

Weber, M. et al. MINSTED nanoscopy enters the Ångström localization range. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 569–576 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Particle fusion of super-resolution data reveals the unit structure of Nup96 in Nuclear Pore Complex. Sci. Rep. 13, 13327 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Nanoscale subcellular architecture revealed by multicolor three-dimensional salvaged fluorescence imaging. Nat. Methods 17, 225–231 (2020).

Chung, K. K. H. et al. Fluorogenic DNA-PAINT for faster, low-background super-resolution imaging. Nat. Methods 19, 554–559 (2022).

Nikic, I. et al. Debugging eukaryotic genetic code expansion for site-specific Click-PAINT super-resolution microscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 16172–16176 (2016).

Mihaila, T. S. et al. Enhanced incorporation of subnanometer tags into cellular proteins for fluorescence nanoscopy via optimized genetic code expansion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2201861119 (2022).

Bourg, N. et al. Direct optical nanoscopy with axially localized detection. Nat. Photonics 9, 587–593 (2015).

Dasgupta, A. et al. Direct supercritical angle localization microscopy for nanometer 3D superresolution. Nat. Commun. 12, 1180 (2021).

Chizhik, A. I., Rother, J., Gregor, I., Janshoff, A. & Enderlein, J. Metal-induced energy transfer for live cell nanoscopy. Nat. Photonics 8, 124–127 (2014).

Ghosh, A. et al. Graphene-based metal-induced energy transfer for sub-nanometre optical localization. Nat. Photonics 13, 860–865 (2019).

Szalai, A. M. et al. Three-dimensional total-internal reflection fluorescence nanoscopy with nanometric axial resolution by photometric localization of single molecules. Nat. Commun. 12, 517 (2021).

Jungmann, R. et al. Multiplexed 3D cellular super-resolution imaging with DNA-PAINT and Exchange-PAINT. Nat. Methods 11, 313–318 (2014).

Masullo, L. A. et al. Spatial and stoichiometric in situ analysis of biomolecular oligomerization at single-protein resolution. Nat. Commun. 16, 4202 (2025).

Honsa, M. et al. Imaging ligand–receptor interactions at single-protein resolution with DNA-PAINT. Small Methods 9, e2401799 (2025).

Ostersehlt, L. M. et al. DNA-PAINT MINFLUX nanoscopy. Nat. Methods 19, 1072–1075 (2022).

Unterauer, E. M. et al. Spatial proteomics in neurons at single-protein resolution. Cell 187, 1785–1800 (2024).

Schueder, F. et al. Unraveling cellular complexity with transient adapters in highly multiplexed super-resolution imaging. Cell 187, 1769–1784 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Implementation of a 4Pi-SMS super-resolution microscope. Nat. Protoc. 16, 677–727 (2021).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Elucidating subcellular architecture and dynamics at isotropic 100-nm resolution with 4Pi-SIM. Nat. Methods 22, 335–347 (2025).

Cnossen, J., Cui, T. J., Joo, C. & Smith, C. Drift correction in localization microscopy using entropy minimization. Opt. Express 29, 27961–27974 (2021).

Ries, J. SMAP: a modular super-resolution microscopy analysis platform for SMLM data. Nat. Methods 17, 870–872 (2020).

Geertsema, H. J. et al. Left-handed DNA-PAINT for improved super-resolution imaging in the nucleus. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 551–554 (2021).

Sograte-Idrissi, S. et al. Nanobody detection of standard fluorescent proteins enables multi-target DNA-PAINT with high resolution and minimal displacement errors. Cells 8, 48 (2019).

Koch, B. et al. Generation and validation of homozygous fluorescent knock-in cells using CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1465–1487 (2018).

Wang, Q., Zheng, B. and Zhang, Y. Example dataset for ‘4Pi-SIMFLUX: 4Pi single-molecule localization microscopy with structured illumination’. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30022948.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Gu at the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for guidance on SIMFLUX data analysis, Q. Xie at Westlake University for sharing the pSin-GFP plasmid and J. Bewersdorf at Yale University for sharing the mCherry-KDEL plasmid. Y. Zhang acknowledges support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3400600) and the National Science Foundation of China (32150015, 32471516). X.Y. acknowledges support from the ‘Pioneer’ and ‘Leading Goose’ R&D Program of Zhejiang (2024SSYS0033). Y.L. is supported in part by the ZJU-UIUC Institute of Zhejiang University. This work was also supported by the State Key Laboratory of Gene Expression, the Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine, the Westlake Education Foundation and the Research Center for Industries of the Future at Westlake University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Zhang conceived the idea and supervised the project. Q.W. designed and built the optical system and performed imaging. B.Z. developed and optimized DNA-PAINT imaging. Z.Y. and Q.D. generated the stable COS-7 cell line of Ensconsin. Z.Y. generated the Nup96 CRISPR cell line. B.Z., Y. Zhan, Q.D. and Y.Q. optimized and prepared biological samples. L.C. and X.Y. prepared the synaptonemal complex samples. Q.W., X.W., S.L. and Y.L. implemented the software and performed data analysis. Y. Zhang, Q.W. and B.Z. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y. Zhang, Q.W. and B.Z. have filed a patent application on 4Pi-SIMFLUX described in this work. Y. Zhang is co-inventor of a US patent (US11209367B2) related to the salvaged fluorescence method used in this work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Methods thanks Alan M. Szalai and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Rita Strack and Nina Vogt, in collaboration with the Nature Methods team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Performance comparison of 3D-SMLM, 4Pi-SMLM, and 4Pi-SIMFLUX.

a-c, Side-by-side comparison of localization precision for 3D-SMLM (a), 4Pi-SMLM (b), and 4Pi-SIMFLUX (c). d, Localization precision of 4Pi-SIMFLUX at the focal plane with different photon numbers. The black dashed line denotes 1 nm localization precision. All three simulation experiments were performed using a vectorial PSF model with identical parameters: objective NA = 1.35; medium refractive index = 1.406; emission wavelength = 600 nm; pixel size = 120 nm. For 3D localization and phase-wrapping, an astigmatism of 60 nm in amplitude (root mean square error) was introduced to the pupil function to generate PSFs with elliptical patterns. For 3D-SMLM, the photon count was 4,000 per image with a background of 12 photons per pixel. For 4Pi-SMLM, the photon count was 2,000 per phase image (total of 8,000 photons) with a background of 24 photons per pixel. For 4Pi-SIMFLUX, the 2,000 photons in each phase image were distributed among the six sub-images according to the corresponding excitation patterns (total of 8,000 photons) with a background of 24 photons per pixel. Only Poisson noise was considered. The 4Pi-SIMFLUX illumination pattern was simulated with a modulation depth of 0.9 and an interference period of 210 nm, mimicking experimental conditions. For each z position in all images, 50,000 molecules were simulated. Localization precision was calculated as the standard deviation of the estimated positions.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Optical layout of 4Pi-SIMFLUX.

Refer to the Methods section for a detailed description. a, Structured illumination path. b, Fluorescence detection path. c, Focus-lock and salvaged fluorescence detection paths. AOTF: acousto-optic tunable filter; SMF: single-mode fiber; HWP: half-wave plate; SLM: spatial light modulator; FSW: four-segmented wave plate; DM1-4: dichroic mirror; QWP1-3: quarter-wave plate; Def. M1, 2: deformable mirror; NPBS: nonpolarizing beam splitter; AP1, 2: aperture; PBS: polarizing beam splitter; F1, 2: emission filter; L1-L16: lens; M1-M16: mirror; CY1: cylindrical lens; CAM1: sCMOS camera; CAM2: EMCCD camera; CAM3: CMOS camera.

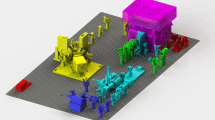

Extended Data Fig. 3 SolidWorks design of 4Pi-SIMFLUX.

a-c, Overview (a), front view (b), and side view (c) of the SolidWorks model of 4Pi-SIMFLUX. d, SolidWorks design of the structured illumination path. e, SolidWorks model of the SLM mount with a 10° tilt.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Synchronization diagram of 4Pi-SIMFLUX.

The SLM served as the initial trigger signal, which was transmitted to the sCMOS camera with a 1 ms delay. The EMCCD was triggered once every six sCMOS exposures, and the AOTF remained open. One full 4Pi-SIMFLUX imaging cycle is 36 ms.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Algorithm flowchart for 4Pi-SIMFLUX reconstruction.

Refer to the Methods section and Supplementary Note 2 for a detailed description. Rough XY ① and Z positions ② were estimated by MLE fitting with an elliptical Gaussian PSF model. 4Pi-SIMFLUX integrates SIMFLUX’s precise XY positions ③ and 4Pi-SMLM’s precise Z position ④ to obtain precise XYZ positions ⑤. In filtering step 1, molecules that are not fluorescent in all six frames were rejected using two filters: photon asymmetry ratio and modulation depth. In filtering step 2, molecules were rejected using other filters such as photon number, localization precision and interference contrast. Please see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Note 2 for details.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Sample mounting for 4Pi-SIMFLUX.

a, Overview of sample mounting in 4Pi-SIMFLUX. The upper left picture shows the sample mounting between the two objectives. b, Exploded view of the sample holder and coverslip assembly. c, Blueprint of the sample mount.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Illumination grating periods and modulation depth of 4Pi-SIMFLUX.

a,b, The cross-correlation spectrum of the 0th and +1st order components in the x- or y-direction. The white dots within the red circles indicate the wavevector’s magnitude and orientation of the structured illumination, corresponding to the illumination grating periods of 210 nm (x-direction) and 209 nm (y-direction), respectively. c,d, Experimental modulation depths estimated from single molecules in the dataset shown in Fig. 3a are 0.91 and 0.92 in the x- or y-direction, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Resolution analysis for 4Pi-SIMFLUX in mitochondria imaging.

The mitochondria image shown in Fig. 5d was reconstructed from four optical sections. a, DAFL precision of molecules from each optical section. b, FRC resolution for each optical section. c, Distributions of 3D localization results from molecules emitting ≥10 frames. The photon count for these molecules is 4,478 ± 1,631 (mean ± s.d.). d, Histograms of the distributions in c were fit with Gaussian functions, and the standard deviations are reported.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 and Notes 1–3.

Supplementary Video 1

The video shows the SolidWorks model of the 4Pi-SIMFLUX microscope (see also Extended Data Fig. 3). A detailed description of the optical components can be found in the Methods section.

Supplementary Video 2

The video shows the 3D rendering of the nuclear pore complex in a fixed U-2 OS cell, reconstructed with 4Pi-SIMFLUX (see also Fig. 3a–c).

Supplementary Video 3

The video shows the 3D rendering of the nuclear pore complex, reconstructed with 4Pi-SIMFLUX, following particle averaging and cluster analysis (see also Fig. 3f).

Supplementary Video 4

The video shows the 3D rendering of clathrin in a fixed SK-MEL-28 cell, reconstructed with 4Pi-SIMFLUX (see also Fig. 3g–k).

Supplementary Video 5

The video shows the 3D rendering of ER in a fixed COS-7 cell, reconstructed with 4Pi-SIMFLUX (see also Fig. 5a–c).

Supplementary Video 6

The video shows the 3D rendering of mitochondria in a fixed HeLa cell, reconstructed with 4Pi-SIMFLUX (see also Fig. 5d,e).

Supplementary Video 7

The video shows the 3D rendering of synaptonemal complexes in a fixed mouse spermatocyte, reconstructed with 4Pi-SIMFLUX (see also Fig. 5f–h).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Zheng, B., Yu, Z. et al. 4Pi-SIMFLUX: 4Pi single-molecule localization microscopy with structured illumination. Nat Methods 23, 175–182 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02908-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02908-8