Abstract

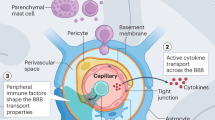

To protect the body from infections, the brain has evolved the ability to coordinate behavioral and immunological responses. The conditioned immune response (CIR) is a form of Pavlovian conditioning wherein a sensory (for example, taste) stimulus, when paired with an immunomodulatory agent, evokes aversive behavior and an anticipatory immune response after re-experiencing the taste. Although taste and its valence are represented in the anterior insular cortex and immune response in the posterior insula and although the insula is pivotal for CIRs, the precise circuitry underlying CIRs remains unknown. Here, we demonstrated that a bidirectional circuit connecting the anterior and posterior (aIC–pIC) insula mediates the CIR in male mice. Retrieving the behavioral dimension of the association requires activity of aIC-to-pIC neurons, whereas modulating the anticipatory immunological dimension requires bidirectional projections. These results illuminate a mechanism by which experience shapes interactions between sensory internal representations and the immune system. Moreover, this newly described intrainsular circuit contributes to the preservation of brain-dependent immune homeostasis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data collected for this study are freely available via FigShare at https://figshare.com/s/19201dd69c005bedf5f9?file=46465708 (ref. 72).

Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No custom software code was used in the research.

References

Willyard, C. How gut microbes could drive brain disorders. Nature 590, 22–25 (2021).

Mohajeri, M. H. et al. The role of the microbiome for human health: from basic science to clinical applications. Eur. J. Nutr. 57, 1–14 (2018).

Osterhout, J. A. et al. A preoptic neuronal population controls fever and appetite during sickness. Nature 606, 937–944 (2022).

Pavlov, I. Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex (Oxford University Press, 1927).

Schedlowski, M. & Pacheco-López, G. The learned immune response: Pavlov and beyond. Brain Behav. Immun. 24, 176–185 (2010).

Cohen, N., Moynihan, J. A. & Ader, R. Pavlovian conditioning of the immune system. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 105, 101–106 (1994).

Janz, L. J. et al. Pavlovian conditioning of LPS-induced responses: effects on corticosterone, splenic NE, and IL-2 production. Physiol. Behav. 59, 1103–1109 (1996).

Oberbeck, R., Kromm, A., Exton, M. S., Schade, U. & Schedlowski, M. Pavlovian conditioning of endotoxin-tolerance in rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 17, 20–27 (2003).

Ader, R. & Cohen, N. Behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression. Psychosom. Med. 37, 333–340 (1975).

Hadamitzky, M., Lückemann, L., Pacheco-López, G. & Schedlowski, M. Pavlovian conditioning of immunological and neuroendocrine functions. Physiol. Rev. 100, 357–405 (2020).

Pacheco-López, G. & Bermúdez-Rattoni, F. Brain–immune interactions and the neural basis of disease-avoidant ingestive behaviour. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 366, 3389–3405 (2011).

Barnéoud, P., Neveu, P. J., Vitiello, S., Mormède, P. & Le Moal, M. Brain neocortex immunomodulation in rats. Brain Res. 474, 394–398 (1988).

Dantzer, R. Neuroimmune interactions: from the brain to the immune system and vice versa. Physiol. Rev. 98, 477–504 (2018).

Sergeeva, M., Rech, J., Schett, G. & Hess, A. Response to peripheral immune stimulation within the brain: magnetic resonance imaging perspective of treatment success. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 268 (2015).

Gehrlach, D. A. et al. A whole-brain connectivity map of mouse insular cortex. eLife 9, e55585 (2020).

Yiannakas, A. et al. Parvalbumin interneuron inhibition onto anterior insula neurons projecting to the basolateral amygdala drives aversive taste memory retrieval. Curr. Biol. 31, 2770–2784 (2021).

Koren, T. et al. Insular cortex neurons encode and retrieve specific immune responses. Cell 184, 5902–5915 (2021).

Levitan, D. et al. Single and population coding of taste in the gustatory cortex of awake mice. J. Neurophysiol. 122, 1342–1356 (2019).

Bergeron, D., Obaid, S., Fournier-Gosselin, M. P., Bouthillier, A. & Nguyen, D. K. Deep brain stimulation of the posterior insula in chronic pain: a theoretical framework. Brain Sci. 11, 639 (2021).

Chen, K., Kogan, J. F. & Fontanini, A. Spatially distributed representation of taste quality in the gustatory insular cortex of behaving mice. Curr. Biol. 31, 247–256 (2021).

Pritchard, T. C., Macaluso, D. A. & Eslinger, P. J. Taste perception in patients with insular cortex lesions. Behav. Neurosci. 113, 663–671 (1999).

Exton, M. S., Bull, D. F., King, M. G. & Husband, A. J. Behavioral conditioning of endotoxin-induced plasma iron alterations. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 50, 675–679 (1995).

Raduolovic, K., Mak’Anyengo, R., Kaya, B., Steinert, A. & Niess, J. H. Injections of lipopolysaccharide into mice to mimic entrance of microbial-derived products after intestinal barrier breach. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 57610 (2018).

Tateda, K., Matsumoto, T., Miyazaki, S. & Yamaguchi, K. Lipopolysaccharide-induced lethality and cytokine production in aged mice. Infect. Immun. 64, 769–774 (1996).

Sun, W. et al. Ilexgenin A, a novel pentacyclic triterpenoid extracted from Aquifoliaceae shows reduction of LPS-induced peritonitis in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 797, 94–105 (2017).

Víctor, V. M. & de la Fuente, M. Comparative study of peritoneal macrophage functions in mice receiving lethal and non-lethal doses of LPS. J. Endotoxin Res. 6, 235–241 (2000).

Auger, M. J. & Ross, J. A. in The Macrophage (eds Lewis, C. E., & McGee, J.O.D.) 1–74 (Oxford University Press, 1993).

Bosurgi, L. et al. Macrophage function in tissue repair and remodeling requires IL-4 or IL-13 with apoptotic cells. Science 356, 1072–1076 (2017).

Ginhoux, F. & Jung, S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 392–404 (2014).

Meng, F. & Lowell, C. A. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophage activation and signal transduction in the absence of Src-family kinases Hck, Fgr, and Lyn. J. Exp. Med. 185, 1661–1670 (1997).

Liao, C. T. et al. Peritoneal macrophage heterogeneity is associated with different peritoneal dialysis outcomes. Kidney Int. 91, 1088–1103 (2017).

Soskic, B., Qureshi, O. S., Hou, T. & Sansom, D. M. A transendocytosis perspective on the CD28/CTLA-4 pathway. Adv. Immunol. 124, 95–136 (2014).

Subauste, C. S., de Waal Malefyt, R. & Fuh, F. Role of CD80 (B7.1) and CD86 (B7.2) in the immune response to an intracellular pathogen. J. Immunol. 160, 1831–1840 (1998).

Akdis, M. et al. Interleukins, from 1 to 37, and interferon-γ: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 701–721 (2011).

Ramírez-Amaya, V. et al. Insular cortex lesions impair the acquisition of conditioned immunosuppression. Brain Behav. Immun. 10, 103–114 (1996).

Kayyal, H. et al. Insula to mPFC reciprocal connectivity differentially underlies novel taste neophobic response and learning in mice. eLife 10, e66686 (2021).

Kayyal, H. et al. Activity of insula to basolateral amygdala projecting neurons is necessary and sufficient for taste valence representation. J. Neurosci. 39, 9369–9382 (2019).

Chandran, S. K. et al. Intrinsic excitability in layer IV–VI anterior insula to basolateral amygdala projection neurons correlates with the confidence of taste valence encoding. eNeuro 10, ENEURO.0302-22.2022 (2023).

Samuelsen, C. L. & Fontanini, A. Behavioral/cognitive processing of intraoral olfactory and gustatory signals in the gustatory cortex of awake rats. J. Neurosci. 37, 244–257 (2017).

Thiels, E. & Klann, E. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 327–345 (2001).

Adaikkan, C. & Rosenblum, K. The role of protein phosphorylation in the gustatory cortex and amygdala during taste learning. Exp. Neurobiol. 21, 37–51 (2012).

David Sweatt, J. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J. Neurochem. 76, 1–10 (2001).

Rosenblum, K. in Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference (Byrne, J. H., ed) 217–234 (Elsevier, 2008).

Cohen-Matsliah, S. I., Brosh, I., Rosenblum, K. & Barkai, E. A novel role for extracellular signal-regulated kinase in maintaining long-term memory-relevant excitability changes. J. Neurosci. 27, 12584–12589 (2007).

Nabel, E. M. et al. Adolescent frontal top–down neurons receive heightened local drive to establish adult attentional behavior in mice. Nat. Commun. 11, 3983 (2020).

Roth, B. L. DREADDs for neuroscientists. Neuron 89, 683–694 (2016).

Mirakaj, V., Dalli, J., Granja, T., Rosenberger, P. & Serhan, C. N. Vagus nerve controls resolution and pro-resolving mediators of inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 211, 1037–1048 (2014).

Goodman, J. R. & Dando, R. To detect and reject, parallel roles for taste and immunity. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 10, 137–145 (2021).

Gogolla, N. The insular cortex. Curr. Biol. 27, R580–R586 (2017).

Uddin, L. Q., Nomi, J. S., Hébert-Seropian, B., Ghaziri, J. & Boucher, O. Structure and function of the human insula. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 34, 300–306 (2017).

Taddio, M. F. et al. In vivo imaging of local inflammation: monitoring LPS-induced CD80/CD86 upregulation by PET. Mol. Imaging Biol. 23, 196–207 (2021).

Nolan, A. et al. Differential role for CD80 and CD86 in the regulation of the innate immune response in murine polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS ONE 4, e6600 (2009).

Rabin, R. in Encyclopedia of Hormones (Henry, H. L. & Normal, A. W.) 255–263 (Elsevier, 2003).

Beurel, E. & Jope, R. S. Lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-6 production is controlled by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and STAT3 in the brain. J. Neuroinflammation 6, 9 (2009).

Harrison, N. A. et al. Inflammation causes mood changes through alterations in subgenual cingulate activity and mesolimbic connectivity. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 407–414 (2009).

Corradi, L., Bruzzone, M., Maschio, Mdal, Sawamiphak, S. & Filosa, A. Hypothalamic galanin-producing neurons regulate stress in zebrafish through a peptidergic, self-inhibitory loop. Curr. Biol. 32, 1497–1510 (2022).

Cummings, K. A. & Clem, R. L. Prefrontal somatostatin interneurons encode fear memory. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 61–74 (2019).

Critchley, H. D. & Harrison, N. A. Visceral influences on brain and behavior. Neuron 77, 624–638 (2013).

Hansen, M. K. et al. Effects of vagotomy on lipopolysaccharide-induced brain interleukin-1β protein in rats. Auton. Neurosci. 85, 119–126 (2000).

Engler, H. et al. Acute amygdaloid response to systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 25, 1384–1392 (2011).

Dumitriu, A. & Popescu, B. O. Placebo effects in neurological diseases. J. Med. Life 3, 114–121 (2010).

Che, N. et al. Impaired B cell inhibition by lupus bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells is caused by reduced CCL2 expression. J. Immunol. 193, 5306–5314 (2014).

Laky, K., Evans, S., Perez-Diez, A. & Fowlkes, B. J. Notch signaling regulates antigen sensitivity of naive CD4+ T cells by tuning co-stimulation. Immunity 42, 80–94 (2015).

Chakraborty, D., Fedorova, O. V., Bagrov, A. Y. & Kaphzan, H. Selective ligands for Na+/K+-ATPase α isoforms differentially and cooperatively regulate excitability of pyramidal neurons in distinct brain regions. Neuropharmacology 117, 338–351 (2017).

Kaphzan, H. et al. Genetic reduction of the α1 subunit of Na/K-ATPase corrects multiple hippocampal phenotypes in Angelman syndrome. Cell Rep. 4, 405–412 (2013).

Sharma, V. et al. Local inhibition of PERK enhances memory and reverses age-related deterioration of cognitive and neuronal properties. J. Neurosci. 38, 648–658 (2017).

Song, C., Ehlers, V. L. & Moyer, J. R. Trace fear conditioning differentially modulates intrinsic excitability of medial prefrontal cortex–basolateral complex of amygdala projection neurons in infralimbic and prelimbic cortices. J. Neurosci. 35, 13511–13524 (2015).

Gulledge, A. T. et al. A sodium-pump-mediated afterhyperpolarization in pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 33, 13025–13041 (2013).

Andrade, R., Foehring, R. C. C., Tzingounis, A. V. V., Cherubini, E. & Storm, J. F. The calcium-activated slow AHP: cutting through the Gordian knot. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 6, 47 (2012).

Song, C. & Moyer, J. R. Layer- and subregion-specific differences in the neurophysiological properties of rat medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 119, 177–191 (2018).

Müller, P. A. et al. Microbiota modulate sympathetic neurons via a gut–brain circuit. Nature 583, 441–446 (2020).

Kayyal, H. et al. An anterior–posterior insula circuit mediates retrieval of conditioned immune response in mice. Figshare https://figshare.com/s/19201dd69c005bedf5f9?file=46465708 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the current members of laboratory of K.R. and M. Amar for their help and support and N. Gould (Oxford University) for critical reading of the manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge technical assistance from the Bioimaging Unit at the University of Haifa, specifically B. Shklyar and L. Simchi, for their expertise in imaging and data acquisition. We thank the veterinary team led by B. Carmi and C. Dollingher and the technical team headed by Y. Bellehsen for their support in animal care and maintenance. This research was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (ISF; ISF 946/17 ISF 258/20 (to K.R.), ISF 1207/22 (to A.A.) and DFG 48998 (to K.R.)). We would like to thank S. Stern (Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience) for hosting and guiding F.C. in her laboratory following the unstable situation in Israel. All main figures and Extended Data figures, except Extended Data Fig. 1, were created using BioRender (665857182).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K., F.C. and S.K.C. led the project. H.K., F.C., E.E., S.S.-Z., A.Y., A.R., A.A. and S.K.C. designed the research, and K.R. designed and supervised the research. H.K., F.C., E.E., S.S.-Z., A.Y., T.K. and S.K.C. performed the research. H.K., F.C., E.E., S.S.-Z., A.A., A.Y., K.R. and S.K.C. analyzed the data. H.K., F.C., E.E. and K.R. wrote the paper. All authors read and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks Yoav Livneh, Manfred Schedlowski and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Immunological Characterization of CIR.

Upper box: Gating strategy. Peritoneal cells were gated on a forward scatter (FSC)/side scatter (SSC) plot (I) and FSC-W FSC-H to identify single cells (II). (III) Lymphocytes were gated to determine macrophages and monocyte populations. F4/80 + Ly6C- cells we re-gated to determine CD80 (IV) and CD86 (V) positive cells. Blue Box: ILs concentration in the peritoneal lavage. a)[IL1b]:LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0.3500 ± 0.2391 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.1072. b) [IL-2]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0.1167 ± 0.0792 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0285. c) [IL-4]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). d) [IL-5]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). e) [IL-6]:LPS-LPS (6.120 ± 1.968 pg/ml) higher than LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p < 0.0001), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p < 0.0001), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p < 0.0001) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p = 0.0003) Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.0001. f) [IL-10]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). g) [IL-12]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml; p < 0.0001), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). h) [IL-13] higher in water (34.84 ± 11.24 pg/ml) than vehicle (3.117 ± 1.473 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, p = 0.0107). CIR (9.950 ± 3.298 pg/ml), LPS-water (21.13 ± 9.019 pg/ml) and LPS-LPS (7.980 ± 2.038 pg/ml) (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0242) i) [IL-17]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) j) [IL-17F]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). k) [IL-21] LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). l) [IL-22]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). m) [IL-28]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). n) [IFNG]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). o) [MIP3a] for LPS-LPS (5.700 ± 1.834 pg/ml) higher than LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p = 0.0008), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p = 0.0008), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p = 0.0014) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml, p = 0.0026) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0002. p) [TGFb1]: LPS-water (238.7 ± 197.9 pg/ml), vehicle (1476 ± 832.9 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0389). q) [TNFa]: LPS-water (14.57 ± 4.932 pg/ml), vehicle (13.67 ± 4.067 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (7.440 ± 2.613 pg/ml), CIR (15.3 ± 5.192 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.1661. Red Box: ILs concentration in the blood. A) [IL-1b]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0.8800 ± 0.6591 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml), water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0801. B) [IL-2]: LPS-water (0.5 ± 0.3141 pg/ml), vehicle (1.133 ± 0.500 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (1.22 ± 05877 pg/ml), CIR (0.18 ± 0.12 pg/ml), water (0.12 ± 0.08 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.4879. C), [IL-4]: LPS-water (0.18 ± 0.18 pg/ml), vehicle (6.050 ± 2.962 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (3.817 ± 2.252 pg/ml), water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0386. D) [IL-5]: CIR (38.20 ± 11.08 pg/ml), water (13.66 ± 9.609 pg/ml), LPS-water (26.78 ± 12.28 pg/ml), vehicle (45.80 ± 24.51 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (42.64 ± 20.51 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0800. E) [IL-6] for LPS-LPS (2568 ± 1240 pg/ml) higher than LPS-water (0.0333 ± 0.02108 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons, p = 0.0184), vehicle (0.0500 ± 0.03416 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons, p = 0.0237), CIR (0.1667 ± 0.1085 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons, p = 0.0438) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons, p = 0.0021) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0024. F) [IL-10]; LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml), water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). G) [IL-12]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml), water (0 ± 0 pg/ml).H) [IL-13]: LPS-water (15.47 ± 5.689 pg/ml), vehicle (14.40 ± 4.231 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (7.575 ± 1.227 pg/ml), CIR (16.17 ± 7.980 pg/ml), water (20.80 ± 8.240 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.6901. I) [IL-17} lower in LPS-LPS (0.800 ± 0.4243 pg/ml) than CIR (0 ± 0, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, p = 0.0496) and vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, p = 0.0496) groups, but not from LPS-Water (0.350 ± 0.180 pg/ml) and water (0.05 ± 0.05 pg/ml) groups (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0164). J) [IL-17F]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml), water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). K) [IL-21]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). L) [IL-22]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml), water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). M)[IL-28]: LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), vehicle (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), CIR (0 ± 0 pg/ml) and water (0 ± 0 pg/ml). N)[IFNG]: CIR (83.68 ± 39.13 pg/ml), vehicle (88.97 ± 38.92 pg/ml), LPS-water (0 ± 0 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (0 ± 0 pg/ml), water (0 ± 0 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0036. O) [MIP3a] for LPS-LPS (2561 ± 688.5 pg/ml) higher than LPS-water (17.32 ± 3,934 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, p = 0.0206) and vehicle (8.320 ± 1.670 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, p = 0.0009) groups, and but not significantly different than CIR (60.27 ± 13.95 pg/ml) and water (101.7 ± 71.25 pg/ml) (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0012). P) [TGFb1]: LPS-water (957.1 ± 469.5 pg/ml), vehicle (1208 ± 1057 pg/ml), LPS-LPS (2939 ± 1895 pg/ml), CIR (1664 ± 872.4 pg/ml), water (151.8 ± 88.02 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.8556.Q)[TNFa] for vehicle (45.52 ± 16.50 pg/ml) higher than water (2.420 ± 1.501 pg/ml, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, p = 0.0101), but not significantly different than LPS-LPS (9.00 ± 5.789 pg/ml), LPS-water (7.917 ± 3.935 pg/ml), CIR (8.250 ± 3.181 pg/ml) Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0113. Data are presented as means ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Extended Data Fig. 2 The peritoneal wall projects to aIC and pIC. CIR increases aIC-to-pIC activated neurons in all the IC subregions.

Representative coronal section from the aIC (a) and the pIC (b) demonstrating PRV+ (green) neurons. Scale bars: mm (top left:500um, top right:40um, bottom left:1 mm, bottom right: 50um). Compatible results were obtained in three different biological repetitions. c) Cell count for EGFP+ cells in the aIC (bregma +1.42), mIC (bregma 0.01), pIC (bregma −0.82) for 3 mice in the same side of the injection or in the opposite side. The arrow indicates the injection coordinates for the rAAV-EGFP. (pIC: m1 ipsi 279.667 ± 33.592, contra 44.333 ± 5.667; m2 ipsi 268.333 ± 7.424, contra 66 ± 4.933; m3 ipsi 194.667 ± 20.202, contra 42.333 ± 1.202. mIC: m1 ipsi 94.667 ± 6.642, contra 51.667 ± 5.364; m2 ipsi 71.667 ± 6.333, contra 22.333 ± 7.688; m3 ipsi 65 ± 2.517, contra 25.667 ± 1.667. aIC: m1 ipsi 131.333 ± 5.044, contra 75.333 ± 4.372; m2 ipsi 101 ± 12.490, contra 26 ± 4.041; m3 ipsi 41 ± 7.211, contra 24.667 ± 3.180). Number of pERK+ neurons in the subregions of aIC and pIC: d) aAIC: CIR (201.2 ± 27.97/mm2), vehicle (159.1 ± 18.60/mm2) p = 0.3660, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U = 14; e) aDIC: CIR (176.1 ± 24.58 cell/mm2), vehicle (119.7 ± 20.16 cell/mm2) p = 0.148, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U = 10.5; f) aGIC: CIR (121.4 ± 22.61/mm2), vehicle (79.41 ± 14.28/mm2) p = 0.1684, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U = 11; g) pAIC: CIR (260.5 ± 31.60 cell/mm2), vehicle (176.7 ± 15.58 /mm2) p = 0.051, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U = 7; h) pDIC: CIR (171.5 ± 31.62 cell/mm2), vehicle (113.5 ± 15.88/mm2) p = 0.1469, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U = 10.5; i) pGIC: CIR (133.2 ± 26.66 cell/mm2), vehicle (83.99 ± 13.51 cell/mm2) p = 0.1807, Mann-Whitney U = 11. Percentage of pERK+ and rAAV+ neurons in the aIC and pIC: j) aAIC: CIR (12.16 ± 1.036%), vehicle (5.850 ± 0.5326%) p = 0.0012, Mann-Whitney U = 0; k) aDIC: CIR (23.33 ± 3.348%), vehicle (9.501 ± 0.9970%) p = 0.0012, Mann-Whitney U = 0; l) aGIC:) CIR (22.47 ± 2.795 %), vehicle (8.232 ± 1.740 %) p = 0.0047, Mann-Whitney U = 2; m) pAIC: CIR (25.93 ± 1.185%), vehicle (17.21 ± 3.596 %) p = 0.0649, Mann-Whitney U = 6; n) pDIC: CIR (24 ± 4.142), vehicle (15.48 ± 2.953 %) p = 0.1797, Mann-Whitney U = 9; o) pGIC: CIR (16.35 ± 6.052%), vehicle (14.94 ± 5.606%) p > 0.9999, Mann-Whitney U = 18. The n of animals for CIR = 6; for vehicle=7. Data presented as means ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001); AIC, agranular IC; DIC, dysgranular IC; GIC, granular IC. Figure was created using BioRender.

Extended Data Fig. 3 CIR retrieval changes intrinsic properties of aIC-pIC projecting neurons.

Intrinsic properties for the aIC-to-pIC neurons (a-l): a, CIR (8.929 ± 1.413 mV, n = 15) showed an increased trend in fast after polarization potentials compared to the vehicle (5.618 ± 1.347 mV, n = 13) group and baseline (5.103 ± 1.347 mV,n = 12) but not significantly different, One-Way ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.1453. N = 8 mice. b, Medium after hyper polarization potentials were similar in the CIR group (-2.905 ± 0.649 mV, n = 15) compared to baseline (-3.376 ± 0.7747 mV, n = 12) and vehicle (-4.714 ± 0.8833 mV, n = 13; One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.2297). c, Slow after polarization potentials were not significantly different in between the CIR (-1.981 ± 0.3811 mV, n = 15), baseline (-1.258 ± 0.5244 mV, n = 12) and vehicle (-2.663 ± 0.755 mV, n = 13; One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.2448). d, The representative traces showing a broader action potential (half-width) in CIR group compared to the control groups (Scale bar 20 mV and 1 ms). e, Both vehicle (49.77 ± 5.435 mV, n = 13) and CIR (51.27 ± 3.183 mV, n = 15) groups showed a trend in decreased action potential amplitude compared to the baseline group (61.75 ± 3.881 mV, n = 12 but not significantly different, One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.1063). f, Action potential half-width is significantly enhanced in CIR group (1.564 ± 0.1862 ms, n = 15) compared to the baseline level (0.8233 ± 0.1083 ms, n = 12) but not significantly different than the vehicle group (1.160 ± 0.1580 ms, n = 13; One-Way ANOVA,Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0082). g, Action potential threshold were not significantly different between the baseline (-33.31 ± 2.520 mV, n = 12), vehicle (-31.22 ± 1.604, mV n = 13), and CIR (-32.78 ± 1.258 mV, n = 15) groups (One-Way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.5168). h, Resting membrane potentials were not significantly different between the baseline (-72.63 ± 1.868 mV, n = 12), vehicle (-71.25 ± 1.524 mV, n = 13), and CIR (-73.52 ± 1.013 mV, n = 15) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.5318). i, Rheobase were not significantly different between the baseline (61.25 ± 9.375 pA, n = 12), vehicle (94.23 ± 13.14 pA, n = 13), and CIR (75.87 ± 11.78 pA, n = 15) groups (One-Way ANOVA,Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0935). j, Input resistance were not significantly different between the baseline (181.6 ± 16.60 MΩ, n = 12), vehicle (162.5 ± 15.45 MΩ, n = 13), and CIR (172.5 ± 13.08 MΩ, n = 15) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.6809). k, Sag ratio were similar in between the baseline (8.497 ± 2.089, n = 12), vehicle (9.182 ± 1.698, n = 13), and CIR (9.260 ± 1.282, n = 15) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.9403). l, The membrane time constants were significantly enhanced in CIR group (26.79 ± 2.008 ms, n = 15) compared to vehicle (21.93 ± 2.407 ms, n = 13) group, but was not significantly different than the baseline (21.12 ± 2.407 ms, n = 12) group (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.0402). Figure was created using BioRender. Intrinsic properties for the pIC-to-aIC neurons (m-x): m, CIR retrieval showed a trend in an increased fast after polarization potentials (8.394 ± 1.841 mV, n = 10) compared to baseline (6.042 ± 1.55 mV, n = 11) and to vehicle (7.46 ± 1.442 mV, n = 13) group, but not significantly different (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.6026). N = 8 mice. n, Medium hyperpolarization potentials were similar in the CIR group (-3.630 ± 1.022 mV, n = 10) compared to baseline (-5.625 ± 1.114 mV, n = 11) and to vehicle (-5363 ± 0.8790 mV, n = 13) groups (One-Way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.2397). o, Slow after polarization potentials were not significantly different in between baseline (-2.674 ± 0.6305 mV, n = 11), vehicle (-2.863 ± 0.3580 mV, n = 13), and CIR (-2.123 ± 0.4064 mV, n = 10) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.5360). p, The representative traces showing a broader activation potential half-width in the CIR group compared to baseline and vehicle groups. Scale bar 20 mV and 1 ms. q, Both vehicle (44.58 ± 4.601 mV, n = 13) and CIR (51.28 ± 2.706 mV, n = 10) groups showed a similar action potential amplitude compared to the baseline group (55.94 ± 5.848 mV, n = 11; One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.2235). r, Action potential half-width is significantly enhanced in CIR group (1.322 ± 0.1499 ms, n = 10) compared to the baseline (0.7864 ± 0.07533 ms, n = 11), but was not significantly different than the vehicle (1.069 ± 0.09027 ms, n = 13) group (One-Way ANOVA,Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0081). s, Action potential threshold were not significantly different between the baseline (-34.10 ± 1.991 mV, n = 11), vehicle (-35.28 ± 12.696, mV n = 13), and CIR (-30.17 ± 2.516 mV, n = 10) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.3374). t, Resting membrane potentials were not significantly different between the baseline (-71.91 ± 1.560 mV, n = 11), vehicle (-69.80 ± 1.537 mV, n = 13), and CIR (-74.46 ± 1.198 mV, n = 10) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.0994). u, Rheobase was not significantly different between the baseline (53.64 ± 6.372 pA, n = 11), vehicle (98.00 ± 19.06 pA, n = 13), and CIR (92.10 ± 12.83 pA, n = 10) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.0835). v, Input resistance was not significantly different between the baseline (188.1 ± 25.87 MΩ, n = 11), vehicle (156.0 ± 24.01MΩ, n = 13), and CIR (160.4 ± 11.36 MΩ, n = 13) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.5493). w, Sag ratio was similar in between the baseline (12.25 ± 2.637, n = 11), vehicle (10.68 ± 2.328, n = 13), and CIR (11.39 ± 1.682, n = 10) groups (One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.8859). x, The membrane time constants were significantly enhanced in CIR group (26.23 ± 2.872 ms, n = 10) compared to vehicle group (16.95 ± 1.915 ms, n = 13), and the baseline (15.48 ± 1.437 ms, n = 11; One-Way ANOVA, p = 0.0027). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Figure was created using BioRender.

Extended Data Fig. 4 synaptic properties of aIC-pIC projecting neurons at baseline and after CIR retrieval.

Synaptic properties of the aIC-pIC neurons differ at their baseline (a-f): a, Representative traces of mEPSCs recorded from LV aIC to pIC and pIC-to-aIC neurons at the baseline without any behavioral manipulations. Scale bar represents 50 pA and 2 Sec. Average of 13-14 cells with similar recordings. N = 7 mice. b, aIC-to-pIC and pIC-to-aIC projecting neurons are similar mEPSCs frequencies at their baseline. (aIC-to-pIC, 0.3881 ± 0.06619 Hz, n = 14 cells; pIC-to-aIC, 0.7923 ± 0.2206 Hz, n = 13 cells; Mann Whitney test, Two-tailed,p = 0.1731). c,aIC-to-pIC and pIC-to-aIC projecting neurons are similar mEPSCs Amplitudes at their baseline. (aIC-to-pIC, 15.40 ± 1.464 pA; pIC-to-aIC, 13.67 ± 1.326 pA; Mann Whitney test,Two-tailed, p = 0.2588). d, Representative traces of mIPSCs recorded from LV aIC to pIC and pIC-to-aIC neurons at the baseline without any behavioral manipulations. Scale bar represents 50 pA and 2 Sec. Average of 12-13 cells with similar recordings. N = 7 mice. e, aIC-to-pIC and pIC-to-aIC projecting neurons are significantly different in mIPSCs Frequencies at their baseline. (aIC-to-pIC, 1.082 ± 0.1363 Hz, n = 13 cells; pIC-to-aIC, 2.028 ± 0.2710 Hz, n = 12 cells; Unpaired t test,Two-tailed, p = 0.0040). f, pIC-to-aIC projecting neurons showed a trend in increased mIPSCs Amplitudes at their baseline. (aIC-to-pIC, 15.03 ± 1.269 pA; pIC-to-aIC, 17.92 ± 2.048 pA; Mann Whitney test,Two-tailed, p = 0.0868). Figure was created using BioRender. Retrieval of CIR does not change the synaptic properties of the pIC-to-aIC (g-l): g, Representative traces of mEPSCs recorded from LV aIC and pIC-to-aIC neurons following the retrieval of CIR and PBS (Vehicle). Scale bar represents 50 pA and 2 Sec. Average of 10-17 cells with similar recordings. N = 5-8 mice. h, Retrieval of CIR shared similar frequencies of mEPSCs on pIC-to-aIC compared to all treatment groups. (Vehicle, 0.5294 ± 0.1270 Hz, n = 17 cells; CIR, 0.4039 ± 0.08858 Hz n = 17 cells; Vehicle General, 0.7217 ± 0.2630 Hz n = 10 cells; CIR General, 0.4833 ± 0.1167 Hz, n = 10 cells). One-Way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.8500. i, Retrieval of CIR shared similar amplitudes of mEPSCs on pIC-to-aIC compared to all other treatment groups. (Vehicle, 14.29 ± 1.256 pA; CIR, 13.89 ± 0.8747 pA; Vehicle General 14.58 ± 0.8882 pA; CIR General, 12.60 ± 1.101 pA). One-Way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.2964. j, Representative traces of mIPSCs recorded from LV aIC and pIC-to-aIC neurons following the retrieval of CIR and PBS (Vehicle). Scale bar represents 50 pA and 2 Sec. Average of 10-17 cells with similar recordings. N = 5-8 mice. k, Retrieval of CIR displayed similar frequencies of mIPSCs on aIC-pIC compared to aIC-pIC (Vehicle), Vehicle non-projection and CIR groups. (Vehicle, 1.124 ± 0.2697 Hz, n = 17; CIR, 1.914 ± 0.4465 Hz, n = 17; Vehicle General, 1.483 ± 0.2106 Hz, n = 10; CIR General, 1.595 ± 0.1571 Hz, n = 10). One-Way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.2330. l, Retrieval of CIR displays similar the amplitude of mIPSCs on pIC-to-aIC compared to pIC-to-aIC Vehicle and non-projection groups following the treatments. (Vehicle, 18.46 ± 1.788 pA; CIR, 15.84 ± 1.617 pA; Vehicle General, 15.78 ± 1.522 pA; CIR General 16.22 ± 0.9356 pA). One-Way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.5985. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Figure was created using BioRender.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Activation of the aIC-pIC pathway resulted in a decrease of the CD80+ monocytes.

a, Schematic representation of behavioral test conducted for inhibition during quinine presentation. b, Aversion index of aIC→pIC (98.0 ± 2.0; n = 5), pIC→aIC (100.0 ± 0; n = 5) and CTRL (97.5 ± 2.5; n = 4) Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.7253. c, Schematic representation of the behavioral test conducted for aIC-pIC activation. d, Aversion index of aIC→pIC (39.13 ± 7.988%), pIC→aIC (16.58 ± 5.759%) and CTRL (26.88 ± 5.571%) Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.7323. e, Schematic representation of behavioral test conducted for aIC-pIC activation. All values were normalized to the water group. f, Percentage of monocyte/macrophage populations in CTRL (Monocytes: 400.379 ± 136.011%; macrophages: 90.398 ± 8.549%), aIC-to-pIC (Monocytes: 356.669 ± 134.076%; macrophages: 103.653 ± 5.254%) and pIC-to-aIC (Monocytes: 261.576 ± 60.394%; macrophages: 98.446 ± 5.588%) 2-way ANOVA; F (1, 14) = 0.4331, p = 0.5212. g, Normalized percentage of CD80+ monocyte population was higher for CTRL (Monocytes: 556.595 ± 121.135%; macrophages:100.824 ± 5.371%) than in aIC-to-pIC (Monocytes:332.596 ± 24.477%; macrophages: 103.711 ± 1.578%; p = 0.0320) or pIC-to-aIC (Monocytes: 318.449 ± 70.663%; macrophages: 100.3654.520 ± ; p = 0.0181) 2-way ANOVA; F (2, 71) = 2.425, p = 0.0958. h, Normalized percentage of CD86+ monocytes/macrophages in CTRL (Monocytes: 24.270 ± 5.184%; macrophages: 148.614 ± 10.098%), aIC-to-pIC (Monocytes: 17.789 ± 4.861%; macrophages: 147.016 ± 8.274%) and pIC-to-aIC (Monocytes: 14.177 ± 5.485%, Macrophages:132.508 ± 5.822%) 2-way ANOVA; F (2, 36) = 2.666, p = 0.0832. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Figure was created using BioRender.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Immunological characterization of LPS representation, aIC-pIC inhibition in absence of behavior and novel taste consumption.

a, Schematic representation of the behavioral test conducted for LPS-LPS inhibition. Water-restricted mice were IP injected with LPS on day 5). On day 9, mice were IP injected with CNO 1 h before another LPS injection; after 3 h they were sacrificed, and peritoneal lavage collected. Monocyte/macrophage populations in peritoneal lavage were determined using immunostaining for F4/80 and Ly6C. All values were normalized to the water group. b, aIC→pIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 539.84 ± 163.80; macrophages: 80.04 ± 13.06); pIC→aIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 1349.11 ± 292.53; macrophages: 51.78 ± 8.29; p = 0.001); CTRL (n = 10; Monocytes: 1232.58 ± 145.13; macrophages: 44.89 ± 3.93; p = 0.0051) 2-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 4.135, p = 0.0271. Monocytes/macrophages were sub-gated and analyzed for CD80+ c) CD86+ d) frequencies. c, aIC→pIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 432.84 ± 220.34; macrophages: 104.86 ± 1.97); pIC→aIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 350.78 ± 76.98; macrophages: 93.09 ± 2.95); CTRL (n = 10; Monocytes: 226.13 ± 21.21; macrophages: 97.75 ± 1.26)2-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.622, p = 0.5444.d, aIC→pIC (n = 10; Monocytes:8.47 ± 5.03; macrophages: 79.71 ± 13.81); pIC→aIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 2.09 ± 0.67; macrophages: 72.55 ± 7.31);CTRL (n = 10; Monocytes: 2.16 ± 0.46; macrophages:78.08 ± 9.13) 2-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.3821, p = 0.6861. e, Schematic representation of the inhibition with no behavior conducted. Water-restricted mice were IP injected with CNO (day 3) and were sacrificed 3 h later. Following CNO administration monocyte/macrophage populations in peritoneal lavage were determined using immunostaining for F4/80 and Ly6C. All values were normalized to the water group. f, aIC→pIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 1095.09 ± 372.58; macrophages:103.97 ± 12.49);pIC→aIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 1044.31 ± 377.63; macrophages: 106.12 ± 11.33);CTRL (n = 8; Monocytes: 730.83 ± 249.93; macrophages: 114.11 ± 8.42) 2-way ANOVA, F(2, 25) = 0.293, p = 0.7486. Monocytes/macrophages were sub-gated and analyzed for CD80+ g) CD86+ h) frequencies. g,aIC→pIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 218.89 ± 93.46; macrophages: 96.97 ± 1.58) pIC→aIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 262.82 ± 83.14; macrophages: 94.95 ± 1.21); CTRL (n = 8; Monocytes: 437.66 ± 204.84; macrophages: 98.64 ± 1.80) 2-way ANOVA, F(2, 25) = 0.7855, P = 0.4668. h, aIC→pIC (n = 10; Monocytes: 5.96 ± 2.89; macrophages: 91.39 ± 8.01), pIC→aIC (n = 10; Monocytes:10.86 ± 4.57; macrophages: 112.88 ± 12.09); CTRL (n = 8; Monocytes: 23.89 ± 12.55; macrophages:120.39 ± 13.17) 2-way ANOVA, F(2, 25) = 4.332; p = 0.0242. i. Schematic representation of novel vs familiar taste paradigm; After water-deprivation for one day, mice were presented with either saccharin (0.5%, familiar saccharin group) or water (novel saccharin group) for 6 consecutive days. On the 8th day, mice were presented with 1 ml of saccharin and sacrificed 3 h later. Peritoneal lavage was collected and percentage of monocyte/macrophage populations (j) was analyzed as well as CD80(k)/CD86(l) expressing cells. All values were normalized to the water group. j. novel saccharin (n = 8; Monocytes: 87.86 ± 15.08%; macrophages: 99.86 ± 2.38%) and familiar saccharin (n = 8; Monocytes: 83.50 ± 9.9%; macrophages: 92.07 ± 2.46%)2-way ANOVA; F (1, 14) = 0.4331, p = 0.5212. k. Novel saccharin (n = 8; Monocytes: 63.98 ± 38.01; macrophages: 98.27 ± 2.26); Familiar saccharin (n = 8; Monocytes: 44.11 ± 14.27; macrophages: 98.03 ± 1.87) 2-way ANOVA; F (1, 14) = 0.2618, p = 0.62. l. Novel saccharin (n = 8; Monocytes: 84.92 ± 7.43; macrophages: 84.66 ± 2.69); Familiar saccharin (n = 8; Monocytes: 91.08 ± 7.86; macrophages: 97.11 ± 4.17) 2-way ANOVA; F (1, 14) = 2.418, p = 0.14. Data are presented as means ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Figure was created using BioRender.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Fig. 2

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Fig. 3

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Fig. 4

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Fig. 5

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Fig. 6

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Data points used for statistical analysis.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kayyal, H., Cruciani, F., Chandran, S.K. et al. Retrieval of conditioned immune response in male mice is mediated by an anterior–posterior insula circuit. Nat Neurosci 28, 589–601 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01864-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01864-4