Abstract

Adult gliomas are incurable primary brain cancers that infiltrate healthy brain and incorporate into neural networks. Gliomas can be classified as low grade or high grade based on histopathological and molecular features, which broadly predicts their aggressiveness. Here we performed patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings from pyramidal neurons and glioma cells from individuals with either low- or high-grade glioma. We find that the biophysical properties of human pyramidal neurons within glioma-infiltrated cortex differ according to tumor grade, with neurons from high-grade glioma being more excitable than those from low-grade glioma. Additionally, glioma cells within high-grade tumors have smaller, longer synaptic responses. Increased neuron–glioma network activity within human high-grade tumor tissue leads to increased glioma proliferation, suggesting that the hyperexcitability of pyramidal neurons in human high-grade glioma may drive tumor growth. Combined, our findings illustrate that high- and low-grade glioma differentially hijack neural networks.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Access to the data is restricted because of the use of human participants, and datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Code availability

Classifier code is available via GitHub at https://github.com/lucympalmer/GlioPathoPNClassifers.git.

References

Claus, E. B. et al. Survival and low-grade glioma: the emergence of genetic information. Neurosurg. Focus 38, E6 (2015).

Hanif, F., Muzaffar, K., Perveen, K., Malhi, S. M. & Simjee Sh, U. Glioblastoma multiforme: a review of its epidemiology and pathogenesis through clinical presentation and treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 18, 3–9 (2017).

Neftel, C. et al. An integrative model of cellular states, plasticity, and genetics for glioblastoma. Cell 178, 835–849 (2019).

Mazor, T. et al. Clonal expansion and epigenetic reprogramming following deletion or amplification of mutant IDH1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10743–10748 (2017).

Verhaak, R. G. W. et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 17, 98–110 (2010).

Wang, Q. et al. Tumor evolution of glioma-intrinsic gene expression subtypes associates with immunological changes in the microenvironment. Cancer Cell 32, 42–56 (2017).

Maher, E. A. et al. Malignant glioma: genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev. 15, 1311–1333 (2001).

Carstam, L. et al. Long-term follow up of patients with WHO grade 2 oligodendroglioma. J. Neurooncol. 164, 65–74 (2023).

Buckner, J. C. et al. Radiation plus procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine in low-grade glioma. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 1344–1355 (2016).

Hicks, W. H. et al. Contemporary mouse models in glioma research. Cells 10, 712 (2021).

Gómez-Oliva, R. et al. Evolution of experimental models in the study of glioblastoma: toward finding efficient treatments. Front. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.614295 (2021).

Venkatesh, H. S. et al. Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature 573, 539–545 (2019).

Venkataramani, V. et al. Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature 573, 532–538 (2019).

Taylor, K. R. et al. Glioma synapses recruit mechanisms of adaptive plasticity. Nature 623, 366–374 (2023).

Venkatesh, H. S. et al. Targeting neuronal activity-regulated neuroligin-3 dependency in high-grade glioma. Nature 549, 533–537 (2017).

Pan, Y. et al. NF1 mutation drives neuronal activity-dependent initiation of optic glioma. Nature 594, 277–282 (2021).

Diaz-Fernandez, B. et al. Differentiation of tumor vs. peritumoral cortex in gliomas by intraoperative electrocorticography. Neuro Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noaf082 (2025).

Krishna, S. et al. Glioblastoma remodelling of human neural circuits decreases survival. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06036-1 (2023).

Feyissa, A. M. et al. High-frequency oscillations in awake patients undergoing brain tumor-related epilepsy surgery. Neurology 90, e1119–e1125 (2018).

Sottoriva, A. et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in human glioblastoma reflects cancer evolutionary dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4009–4014 (2013).

Patel, A. P. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science 344, 1396–1401 (2014).

Suzuki, H. et al. Mutational landscape and clonal architecture in grade II and III gliomas. Nat. Genet. 47, 458–468 (2015).

Puchalski, R. B. et al. An anatomic transcriptional atlas of human glioblastoma. Science 360, 660–663 (2018).

Kalmbach, B. E. et al. Signature morpho-electric, transcriptomic, and dendritic properties of human layer 5 neocortical pyramidal neurons. Neuron 109, 2914–2927 (2021).

Yan, H. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 765–773 (2009).

Han, S. et al. IDH mutation in glioma: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Br. J. Cancer 122, 1580–1589 (2020).

Weller, M. et al. Glioma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1, 15017 (2015).

Osswald, M. et al. Brain tumour cells interconnect to a functional and resistant network. Nature 528, 93–98 (2015).

Weil, S. et al. Tumor microtubes convey resistance to surgical lesions and chemotherapy in gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 19, 1316–1326 (2017).

Labrakakis, C. et al. Action potential-generating cells in human glioblastomas. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 56, 243–254 (1997).

Curry, R. N. et al. Integrated electrophysiological and genomic profiles of single cells reveal spiking tumor cells in human glioma. Cancer Cell 42, 1713–1728 (2024).

Henrik Heiland, D. et al. Tumor-associated reactive astrocytes aid the evolution of immunosuppressive environment in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10493-6 (2019).

Verkhratsky, A., Bush, N., Nedergaard, M. & Butt, A. The special case of human astrocytes. Neuroglia 1, 21–29 (2018).

Verkhratsky, A., Ho, M. S. & Parpura, V. Evolution of neuroglia. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1175, 15–44 (2019).

Venkataramani, V. et al. Glioblastoma hijacks neuronal mechanisms for brain invasion. Cell 185, 2899–2917 (2022).

Bezanilla, F. Ion channels: from conductance to structure. Neuron 60, 456–468 (2008).

Gonzalez-Sulser, A. et al. Hippocampal neuron firing and local field potentials in the in vitro 4-aminopyridine epilepsy model. J. Neurophysiol. 108, 2568–2580 (2012).

Heuzeroth, H., Wawra, M., Fidzinski, P., Dag, R. & Holtkamp, M. The 4-aminopyridine model of acute seizures in vitro elucidates efficacy of new antiepileptic drugs. Front. Neurosci. 13, 677 (2019).

Lévesque, M., Salami, P., Behr, C. & Avoli, M. Temporal lobe epileptiform activity following systemic administration of 4-aminopyridine in rats. Epilepsia 54, 596–604 (2013).

Stensjøen, A. L. et al. Growth dynamics of untreated glioblastomas in vivo. Neuro Oncol. 17, 1402–1411 (2015).

Feucht, D. et al. Preoperative growth dynamics of untreated glioblastoma: description of an exponential growth type, correlating factors, and association with postoperative survival. Neurooncol. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdae053 (2024).

Preussat, K. et al. Expression of voltage-gated potassium channels Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 in human gliomas. Neurosci. Lett. 346, 33–36 (2003).

Schaff, L. R. & Mellinghoff, I. K. Glioblastoma and other primary brain malignancies in adults: a review. JAMA 329, 574–587 (2023).

Schwartzbaum, J. A., Fisher, J. L., Aldape, K. D. & Wrensch, M. Epidemiology and molecular pathology of glioma. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2, 494–503 (2006).

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 5th edn Volume 6 (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2021).

Chen, H. et al. Mutant IDH1 and seizures in patients with glioma. Neurology 88, 1805–1813 (2017).

Yang, R. R. et al. IDH mutant lower grade (WHO Grades II/III) astrocytomas can be stratified for risk by CDKN2A, CDK4 and PDGFRA copy number alterations. Brain Pathol. 30, 541–553 (2020).

Claes, A., Idema, A. J. & Wesseling, P. Diffuse glioma growth: a guerilla war. Acta Neuropathol. 114, 443–458 (2007).

Seker-Polat, F., Pinarbasi Degirmenci, N., Solaroglu, I. & Bagci-Onder, T. Tumor cell infiltration into the brain in glioblastoma: from mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Cancers 14, 443 (2022).

Nomura, M. et al. The multilayered transcriptional architecture of glioblastoma ecosystems. Nat. Genet. 57, 1155–1167 (2025).

Martucci, M. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of primary adult brain tumors: state of the art and future perspectives. Biomedicines 11, 364 (2023).

Al-Okaili, R. N., Krejza, J., Wang, S., Woo, J. H. & Melhem, E. R. Advanced MR imaging techniques in the diagnosis of intraaxial brain tumors in adults. Radiographics 26, S173–S189 (2006).

Pallud, J. et al. Cortical GABAergic excitation contributes to epileptic activities around human glioma. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 244ra289 (2014).

Yu, K. et al. PIK3CA variants selectively initiate brain hyperactivity during gliomagenesis. Nature 578, 166–171 (2020).

Curry, R. N. et al. Glioma epileptiform activity and progression are driven by IGSF3-mediated potassium dysregulation. Neuron 111, 682–695 (2023).

Hausmann, D. et al. Autonomous rhythmic activity in glioma networks drives brain tumour growth. Nature 613, 179–186 (2023).

Venkatesh, H. S. et al. Neuronal activity promotes glioma growth through neuroligin-3 secretion. Cell 161, 803–816 (2015).

Huang-Hobbs, E. et al. Remote neuronal activity drives glioma progression through SEMA4F. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06267-2 (2023).

Buckingham, S. C. et al. Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nat. Med. 17, 1269–1274 (2011).

Campbell, S. L., Buckingham, S. C. & Sontheimer, H. Human glioma cells induce hyperexcitability in cortical networks. Epilepsia 53, 1360–1370 (2012).

Yamaguchi, S. -i & Rogawski, M. A. Effects of anticonvulsant drugs on 4-aminopyridine-induced seizures in mice. Epilepsy Res. 11, 9–16 (1992).

Kostadinova, I. & Danchev, N. 4-aminopyridine – the new old drug for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacia 66, 67–74 (2019).

Brown, D. C. & Gatter, K. C. Ki67 protein: the immaculate deception? Histopathology 40, 2–11 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank G. McDougall for assistance with the glioma cell morphological analysis, and C. Chavez, A. Soch and the Florey Microscopy Facility for assistance with image processing. This work was supported by the NHMRC (grant no. APP2003114, K.J.D. and L.M.P.; grant no. APP2026307, L.M.P.), the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation (L.M.P.), the Brain Cancer Centre (H.M., K.J.D., L.M.P.), the Warren Haynes Fellowship and the Royal Melbourne Hospital Neuroscience Foundation (H.M.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M., K.J.D. and L.M.P. conceptualized and designed the study; H.M. along with M.R., X.W., R.G. and H.G. performed the electrophysiological recordings; J.R., H.M., M.R. and H.G. analyzed all recordings; X.W. and H.G performed the neural reconstructions; Y.H. performed the computational modeling; L.C., C.D. and S.F. provided statistical assistance. V.C.W. assisted with imaging. H.M., K.J.D. and L.M.P. interpreted the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks Jayeeta Basu, Shawn Hervey-Jumper and Frank Winkler for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Intrinsic properties of pyramidal neurons in high- and low-grade glioma.

a, Principal component analysis (PCA) was used for dimension reduction to visualize the collective differences in the biophysical properties of pyramidal neurons from different glioma grades. b-k, Comparison between the properties of pyramidal neurons recorded in high- (blue; n = 104 neurons) and low-grade (green; n = 50 neurons) glioma for (b) Action potential threshold (p = 0.001), (c) Membrane resistance (p = 0.008), (d) Inter-spike interval (p = 0.037), (e) Resting Membrane Potential (RMP; p = 0.602), (f) Total number of action potentials (p = 0.146), (g) Voltage sag (p = 0.217), (h) Action potential rise-time (p = 0.329), (i) Adaptation ratio (p = 0.656), (j) Action potential half-width (p = 0.187) and (k) Action potential delay (p = 0.126). Mean values are represented as bold lines. All data were analyzed using a linear mixed-effect model. ns, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Biophysical properties of human pyramidal neurons in high- vs low-grade glioma from individual patients.

Electrophysiological recordings were averaged and assessed according to individual patients diagnosed with high-grade (n = 32) and low-grade (n = 16) glioma. Trends in Rheobase, Maximum Action Potential (AP) Rate of Rise, AP amplitude and Resting Membrane Potential (RMP) were similar to the analysis performed in individual recordings. a, AP Firing Rate of pyramidal neurons from high- and low-grade glioma in response to somatic current step injections (20 pA, 1200 ms; n = 32 (high), 16 (low) patients). b, Rheobase in pyramidal neurons from high- and low-grade glioma (n = 32 (high), 16 (low) patients; p = 0.015, Mann-Whitney test). c, Maximum AP Rate of Rise (dV/dT) in pyramidal neurons recorded from high- and low-grade glioma (n = 32 (high), 16 (low) patients; p = 0.02, Mann-Whitney test). d, AP phase plot of membrane potential relative to threshold in high- and low-grade glioma (n = 32 (high), 16 (low) patients). e, Peak AP Amplitude in pyramidal neurons in high- and low-grade glioma (n = 32 (high), 16 (low) patients; p = 0.017, Mann-Whitney test). f, RMP in pyramidal neurons from high- and low-grade glioma (n = 32 (high), 16 (low) patients; p = 0.474, Mann-Whitney test). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. ns, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Intrinsic properties of pyramidal neurons classified according to IDH status.

Biophysical properties of neurons recorded from tissue clinically determined as IDH wildtype (WT) or IDH-mutant (mutant). (a-f) Comparison between IDH-WT (light blue; n = 69 cells) and IDH-mutant (light green; n = 85 cells) for action potential (AP) (a) Amplitude (p = 0.0003), (b) Threshold (p = 0.005), (c) Max rate of rise (p = 0.01), (d) Rheobase (p = 0.178), (e) Half-Width (p = 0.328), (f) Rise-time (p = 0.924), (g) Adaptation ratio (p = 0.633), (h) Total number of APs (up to 510 pA), (i) Resting membrane potential (RMP, p = 0.458). Mean values are represented as bold lines. All data were analyzed using a linear mixed-effect model. ns, p > 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Classifier models and their performance in classifying neurons as recorded from high- or low-grade glioma.

a, Two-dimensional projection of training data using DFAC illustrating the separation of high- (blue) and low-grade (green) recordings, in the optimised discriminant (dimension-reduced) space. Performance for one classification test, out of 100 tests with random training data is shown. Large data points represent the centroids for high- (blue) and low-grade (green). b, DFACf projected discriminant scores for both training and test data for the sample shown in (a) illustrating the separation of training and test sets. c, The architecture of the LRC presents that multiple input features (or trace values) are first combined linearly by assigned weights and an intercept (bias), forming a weighted sum, and then this output is transformed by the sigmoid (logistic) activation function, mapping the value to a probability between 0 and 1. A binary prediction can ultimately be made to the model’s confidence on distinguishing the classes. d, The architecture of MLPC depicts an input layer that receives the raw data, which then feeds into a single hidden layer comprising 100 neurons. Each neuron in this hidden layer applies a non-linear activation function (ReLU) to its weighted sum of inputs, whose outputs are then passed to an output layer, producing the final class prediction. e, The classification performance in training strategies (n = 100 tests), including those fed with extracted features (DFACf and LRCf) and raw data (LRCt and MLPCt) (One-way ANOVA). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. f, The performance of DFAC against the number of neurons used for training. Linear regression, R2 = 0.8847. **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Morphological reconstruction of high- and low-grade neurons.

Pyramidal neurons (average somatic depth below pia, 381 ± 21 μm) were filled with the fluorescence marker biocytin-TMR via the patch pipette. Neuron morphology was imaged using confocal microscopy and reconstructed before Sholl analysis was performed. (top) Neuron morphology and (bottom) Number of intersections versus Sholl radius for pyramidal neurons within (a) high-grade and (b) low-grade tissue. c, Comparison between dendritic length and distance from soma for neurons in high-grade (blue; n = 8 cells) ad low-grade (green; n = 6 cells) glioma (p = 0.498, Komogorov-Smirnov test). d, Differences in total length (top; p = 0.852, Mann Whitney test) and intersections (bottom; p = 0.883, Mann Whitney test) for neurons in high-grade (blue; n = 8 cells) and low-grade (green; n = 6 cells) glioma. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. ns, p > 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Glioma cell identification using morphological and electrophysiological properties, immunostaining and sample targeting.

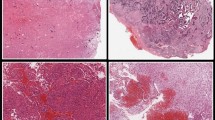

a, Glioma cells were filled with the fluorescent marker biocytin-TMR via the patch pipette and immunostained for the neuro-oncology diagnostic marker, Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP). Confocal image of an example glioma cell filled with biocytin-TMR (left), GFAP (middle) and overlay of TMR and GFAP (right). b, Voltage response to somatic current injection in the glioma cell shown in (a). Inset, zoom of boxed region illustrating spikelet (arrow). c, Voltage clamp recording from the glioma cell shown in (a) and (b) highlighting a spontaneous synaptic current in boxed region. Inset, zoom of boxed region. d, Example histopathology of glioma tissue used for patch clamp recordings which was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). H&E staining was repeated on three independent samples. e, Voltage response to somatic current injection in an example glioma cell from within the tissue sample shown in (d). f, Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) image of a human brain slice highlighting a putative glioma cell (yellow), glia (salmon) and neurons (white).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Glioma cell morphology.

a, Sholl analysis was performed on glioma cells filled with biocytin-TMR. (left) Reconstruction of glioma cell and (right) Number of intersections at distances from the soma (radius of Sholl). The tumor type, grade and sample type (tumor or cortex) are provided for each glioma cell. b, Overlay of Sholl analysis for all reconstructed glioma cells.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Identification of glioma cells.

a, Soma diameter (maximum width) of glioma cells (red; n = 13 cells) and layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons (black; n = 14 cells). p < 0.0001, Mann Whitney test. b, Maximum length of somatic projection in glioma cells (red; n = 13 cells) and glia (black; n = 5 cells). p = 0.025, Mann Whitney test. c, Example voltage response to 330pA somatic current injection in glioma cell (top), glia (middle), layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron (bottom). d, Examples of biocytin-TMR filled glioma. d, (top) Three examples of network connected glioma cells. A single glioma cell was patched and filled with biocytin-TMR (yellow asterisks) which resulted in non-patched cells up to 100 µm away to become fluorescent (pink asterisks), presumably by diffusion of the fluorescent intracellular solution though a tumour microtube connected network. (bottom) Four examples of glioma cells where the TMR was confined to a single cell. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Neural activity is associated with increased glioma proliferation in high-grade glioma.

Confocal images of brain slices from high-grade glioma patients stained with DAPI (blue, for total cell numbers) and Ki67 (orange, to indicate cells replicating). a, Brain slices from patient 2 diagnosed with glioblastoma were incubated for 6 hours in (top) 4AP, (middle) aCSF only, or (bottom) 4AP and tetrodotoxin (4AP + TTX). Ki67 and DAPI staining was performed in three slices. b, The percentage of Ki67 positive cells in slices shown in (a). c, Brain slices from patient 3 (glioblastoma) were incubated for 6 hours in (top) 4AP or (bottom) aCSF. Ki67 and DAPI staining was performed in two slices. d, The percentage of Ki67 positive cells in slices shown in (c). e, Brain slices from patient diagnosed with astrocytoma WHO grade 4 were incubated for 6 hours in (top) 4AP or (bottom) aCSF. Ki67 and DAPI staining was performed in two slices. f, The percentage of Ki67 positive cells in slices shown in (e). Scale bars, 50 µm.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McAlpine, H., Rosier, M., Rozario, J. et al. Increased neural excitability and glioma synaptic activity drives glioma proliferation in human cortex. Nat Neurosci 29, 350–357 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02149-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02149-0

This article is cited by

-

Inhibitory glutamatergic feedback for brain tumor therapy

Medical Oncology (2026)

-

Neural excitability promotes glioma growth

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2025)