Abstract

Winter wheat constitutes approximately 20% of China’s total cereal production. However, calculations of total production based on multiplying the planted area by the yield have tended to produce overestimates. In this study, we generated sample points from existing winter wheat maps and obtained samples for different years using a temporal migration method. Random forest classifiers were then constructed using optimized features extracted from spectral and phenological characteristics and elevation information. Maps of the harvested and planted areas of winter wheat in Chinese eight provinces from 2018 to 2022 were then produced. The resulting maps of the harvested areas achieved an overall accuracy of 95.06% verified by the sample points, and the correlation coefficient between the CROPGRIDS dataset is about 0.77. The harvested area was found to be about 13% smaller than the planted area, which can primarily be attributed to meteorological hazards. This study represents the first attempt to map the winter wheat harvested area at 10–m resolution in China, and it should improve the accuracy of yield estimation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Wheat is one of the most important cereal crops in the world1,2. According to statistics provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the area of wheat harvested worldwide in 2020 was 242 × 106 ha, accounting for 34% of the global grain area1. China’s wheat production, consumption, and imports rank the highest globally. For example, in 2019–2020, the area harvested in the country account for 11% of the global total – the fourth highest worldwide. China also accounted for 18% of global production, second only to the European Union and largely due to winter wheat, which constitutes 95% of the country’s total wheat production3.

Satellite remote sensing technology, with its wide spatial coverage and continuous observation capabilities, has emerged as an effective means of rapidly and efficiently mapping winter wheat. The use of remote sensing for winter wheat mapping has become significantly more convenient and practical2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Using remote sensing-based approaches, the precise geographical locations of winter wheat can be accurately determined and valuable data on growth patterns and yields can be acquired11,12. Numerous studies have employed remote sensing technology to map the geographic distribution of areas planted with winter wheat. These studies utilize various methods, including phenological methods8,13,14,15,16,17, machine learning18,19, and deep learning19,20,21, to provide comprehensive data on crop growth patterns and yields, and this has resulted in the release of related data products. Phenological methods require less training data, which means that they depend less on field surveys8. However, for expansive study areas, intra- and inter-class variations of crop phenological features would occur due to multiple factors, which leads to fluctuations in the effectiveness of these methods22,23,24. Contrastingly, while machine learning and deep learning while machine learning and deep learning excel in large-scale crop classification25,26,27, they encounter two major challenges. Firstly, there is the requirement for a substantial number of accurately labeled samples to train classifiers, typically numbering in the tens of thousands to millions25,26,28,29,30. Secondly, some methodologies rely on high-resolution data at the meter or sub-meter level, which can incur significant costs to procure25,31,32,33. In response to these challenges, researchers have developed models capable of operating with limited labeled data, achieving commendable performance34,35,36,37.

‘Planted area’ refers to the land area where crops are planted, while the harvested area represents the portion harvested from the planted area. From planting to harvesting, crops are susceptible to natural disasters, accidents, and encroachment from construction activity. Consequently, some planted fields do not yield any harvest, resulting in a harvested area that is smaller than the initial planted area. U.S. statistics for the period 1970 to 2017 show that the final harvested area is often less than 85% of the planted area38. As a result, the traditional approach of estimating yield by multiplying the planted area by the yield tends to overestimate the actual production. In addition, previous research examining variations in winter wheat harvested area has demonstrated its sensitivity to climate change39,40. Yield estimates based on the planted area underestimate the true impact of climate change on the overall yield41,42. Therefore, it is critical to accurately distinguish between the planted and harvested areas when mapping winter wheat. Despite some existing studies that address the difference in crop area between planting and harvest, these have predominantly focused on model accuracy without acknowledging the distinction between planted and harvested areas8,24. Moreover, there is a dearth of research specifically dedicated to mapping the harvested area.

In China, the absence of large-scale, high spatial-resolution maps of the harvested winter wheat area persists, primarily due to the scarcity of ground crop sample points. This contrasts with some developed countries that have successfully implemented national crop type maps that are regularly updated with substantial ground truth data43,44. For instance, the United States has established a Cropland Data Layer (CDL), and Canada maintains an Annual Crop Inventory (ACI). However, these maps heavily rely on extensive ground sample data, often necessitating government involvement, and there is often a lag in the data release, with the maps often becoming available up to six months after harvest. One viable approach to address this gap is to generate ground-truth data samples for winter wheat and integrate these with existing planted area data products. It is worth noting that a decrease in the harvested area may not be solely a result of lower model identification accuracy but also a result of various factors, such as floods, drought, wind, hail, and fire occurring in early spring. Additionally, farmers may choose to harvest their crops for fodder earlier than usual, leading to a lower-than-expected harvested area. Government statistics typically rely on total planted area data, which can sometimes overlook crop failures or yield shortfalls in specific regions, which can diminish the accuracy of harvested area data.

As satellite technology continues to advance, offering improved spatial and temporal resolution data, data sources have evolved from the previous 500-m resolution of MODIS to the more refined 10-m resolution provided by Sentinel-2. These technological advances enable the generation of pixel-scale maps of harvested areas, in addition to enhancing the accessibility of data45.

The aim of this study was to accurately map the harvested area of winter wheat in China’s major winter wheat-producing regions. Firstly, we employed sample generation and sample temporal migration methods to generate winter wheat sample points for the period 2018–2022. Subsequently, we utilized winter wheat temporal features extracted from a vegetation index time-series together with auxiliary phenological features and elevation/slope information as inputs to a random forest classifier on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. This approach allowed us to successfully generate maps of the harvested area of winter wheat with a resolution of 10 m.

Methods

Study area

Based on agricultural statistical data, winter wheat is planted in 30 provinces and municipalities in China. This study specially focused on mapping the harvested and planted areas of winter wheat in eight of these provinces and municipalities, which together account for nearly 90% of the country’s winter wheat production3. These provinces and municipalities are located on the Huang–Huai–Hai Plain and include Anhui, Hebei, Henan, Hubei, Jiangsu, Shaanxi, Shandong, and Shanxi (see Fig. 1). In 2020, these eight provinces produced a total of 118.17 million tons of winter wheat, covering a planted area of 19.52 million hectares (https://www.stats.gov.cn/).

Location of study area. The solid black lines mark the provincial boundaries; the grey tiles denote the sub-districts in which the sample points were located. The green dots indicate the location of winter wheat samples, and the blue dots indicate non-wheat samples, including other crops, forest, shrubs, water, buildings, and bare land.

Data acquisition and processing

Remote sensing data

In this study, the classification features were mainly derived from Sentinel-2A/B (S2) Multi-Spectral Instrument (MSI) top-of-atmosphere (TOA) reflectance images (Level-1C) through Google Earth Engine (GEE). All accessible Sentinel-2 TOA images for the period October to June for the years 2017–2022 were obtained. Cloud masking was then applied, resulting in the production of a precise and comprehensive time-series. Previous studies have demonstrated the reliability to observe crops based on TOA reflectance as this captures crucial relative spectral differences among different crop types46. Many recent studies have successfully employed S2 TOA images for crop indentification47,48.

Several other land cover datasets were collected, including the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) land cover product, which has a resolution of 10 m49; this was used to generate samples for identifying non-wheat land cover types. In addition, three winter wheat planted area datasets were used: ChinaWheat30 data (resolution 30 m) for the period 2016 to 20208, PTDTW data (resolution 20 m) on the Huang–Huai–Hai Plain in 2018 (resolution 20 m)13, and ChinaWheat10 data (resolution 10 m) for 2020 to 202224. These datasets vary in terms of temporal and spatial resolution as well as coverage (see Table 1). The ChinaWheat30 data were used to generate samples for the identification of winter wheat. To ensure the accuracy of our planted area product, a cross-validation analysis was subsequently conducted using these three datasets.

Meteorological data

We collected daily data including the wind speed (at 2 pm), maximum air temperature, air pressure, surface temperature, dew point temperature, absolute humidity, and soil moisture from ERA5 datasets50 for May to early June for the five years 2018 to 2022. The severity of hot, dry winds during these months were derived from these data using Chinese national meteorological standards51,52.

In addition, sunshine and precipitation data for 2018 to 2022 were obtained from local meteorological departments. The occurrence of waterlogging in winter wheat was determined by considering factors such as the amount of precipitation, number of precipitation days, and number of sunshine hours. These estimates were again based on standards issued by the China Meteorological Administration53,54.

Statistical data on winter wheat planted area and harvested area

Data on the planted area of winter wheat – in kilohectares (103ha) – in the relevant provinces and municipalities for 2017 to 2022 were acquired from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Among these provinces and municipalities, statistical data on winter wheat planting areas were available for 530 county-level units. We sorted these units by area size and tallied the numbers to determine the grouping for stratified sampling. Based on the histogram shown in Fig. 2(c), we ultimately defined four categories: 0–10, 10–20, 20–40, and >40 thousand hectares. Following a ratio of 2:1:1:1, we selected 50 counties to gather statistical data for verifying the accuracy of planting area estimations. The selected counties are highlighted using polygons on the map shown in Fig. 2(a). The global geo-referenced dataset known as CROPGRIDS has also been collected55, providing area information for 173 crops for the year 2020 at a spatial resolution of 0.05°. Additionally, 700 random points (as shown in Fig. 2(a) and Table 2) were generated to verify the accuracy of the harvested area.

Field survey data

To verify the accuracy of the planted area mapping results, we collected survey samples from multiple sources (Fig. 2 and Table 2): (1) Field surveys were conducted in the sowing years of 2020, and 2022, resulting in 4007, and 128 point samples, respectively; (2) the open-access point samples56,57 for the sowing years of 2018–2021 were downloaded.

Winter wheat classification method

The winter wheat classification consisted of the following steps, as depicted in Fig. 3.

-

(1)

Generating representative sample points for wheat and non-wheat classes (including other crops, forests, shrubs, water, buildings, and bare lands) for the years 2019–2020 using ChinaWheat30 maps and the ESA Land Cover product. In our approach, we initially establish a 50-meter radius buffer around each sample point. A point is retained if the associated land cover type occupies over 90% of the area within this buffer (as shown in Fig. 3(b)). To ensure the accuracy of the sample points, we also incorporate manual examination.

-

(2)

Conducting temporal migration by constructing time-series curves of the winter wheat Near-Infrared Reflectance of vegetation (NIRv) index for different years in each province. The average values for the year 2019–2020 were used as a reference. Migration of the sample points was achieved by comparing the curves for each year except the year 2019–2020 with the reference curve.

-

(3)

Preprocessing the images, which involved cloud removal, temporal compositing, and feature calculation.

-

(4)

Performing classification and accuracy validation by constructing Random Forest classifiers for the identification of winter wheat in Google Earth Engine. Various provincial- and municipality-level accuracy assessment indicators and statistical data were used to evaluate the classification accuracies. Impacts resulting from human factors and meteorological hazards were qualitatively analyzed.

The workflow for mapping the planted and harvested area of winter wheat; RMSE, root-mean-square error; MAE, mean absolute error; R2, the coefficient of determination; UA, user’s accuracy; PA, producer’s accuracy; OA, overall accuracy. The process of screening the generated sample points using wheat as an example (b), where red checkmarks denote retained samples, and blue crosses indicate discarded ones. And (c) and (d) depict the procedure of sample temporal migration using the reference curve.

Sample generation and sample temporal migration

We aggregated the data giving the winter wheat planted area for the five-year period 2016–2020)8 to identify the areas where winter wheat was consistently planted. Then, we established a threshold radius based on the field sizes in different provinces to identify the image elements surrounded by wheat and converted these into a point vector file. Given the non-uniform spatial distribution of the areas planted with winter wheat, our methodology was designed to ensure the representativeness of selected samples while mitigating spatial autocorrelation among them to some extent. This was achieved by overlaying the entire study area with a grid of 0.5° × 0.5° quadrangular tiles (see Fig. 1). Subsequently, the wheat sample points set were derived in equal proportions based on the number of sample points generated within each tile.

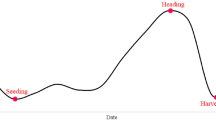

In addition, we conducted temporal migration of the sample points because the generated winter wheat sample points were specific to the year 2019–2020 and could not be directly applied to other years. To accomplish this, we employed a phenology-oriented methodology. Firstly, we computed the mean of the NIRv time series curves for the all samples for the year 2019–2020 to obtain a representative benchmark time-series curve. Then, we compared the sample point curves from earlier years to this reference curve and retained the sample points with the highest degree of similarity. The time-series used spanned the period from October 1 to June 30 of the subsequent year to guarantee the applicability of the migrated samples to the extraction of data from cultivated and harvested areas.

To address the potential errors resulting from variations in climate, agricultural practices, weather conditions, and other factors, we integrated both distance difference and shape similarity metrics to enhance the accuracy of the sample temporal migration. For this, we used the composite distance measure Difference and Similarity Factor (DSF) (Eq. 1), which combines the distance difference factor and shape similarity factor58. The relative distance deviation between two feature sequences (Xi, Yi) is represented by f1 (Eq. 2), with smaller values indicating greater similarity between the sequences. The shape similarity factor between the two sequences is evaluated by f2 (Eq. 3), with larger values indicating greater similarity. The formula used to calculate the DSF is as follows:

For each sample point, the DSF was calculated between the NIRv time series curve and the reference curve. A Gaussian distribution was then fit to the histogram representing the range of similarity scores. In categorizing the sample points as post-migration samples, we applied a threshold of one standard deviation above the mean to remove outliers. Consequently, samples with a similarity score greater than the threshold (i.e., more than one standard deviation above the mean) were discarded, ensuring that only those with typical similarity characteristics were retained for further analysis.

Pre-processing of time-series data and calculation of features

The processing of the time-series data consisted of two steps: (1) generating 10-day composites by computing the median values of the valid S2 observations and (2) filling data gaps through linear interpolation to achieve complete coverage across the temporal domain9. Ultimately, we obtained regular cloud-free and gap-filled 10-day S2 time-series.

Subsequently, we selected ten vegetation indices based on the structure and biochemical characteristics of winter wheat for the construction of spectral features. These indices are listed in Table 3. Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), Green Chlorophyll Vegetation Index (GCVI), and Color Index of Vegetation (CIVE) reflect the chlorophyll level in wheat59, while Excess Green (ExG), Woebbecke Index (WI), and Normalized Green-red Difference Index (NGRDI) indicate the greenness, which is commonly employed for mapping field crops60; Normalized Difference Phenology Index (NDPI) is widely used for extracting winter wheat phenology from remote sensing data61; and Soil-adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) and Land Surface Water Index (LSWI) are known to be sensitive to the total amount of liquid water in vegetation and the soil background62. A strong linear relationship exists between the absorbed photosynthetically active radiation, net photosynthetic rate, leaf area index, and NIRv63.

We employed the following three groups of feature candidates to distinguish between crop types, as shown in Table 4.

-

(1)

Spectral features. We used variations in the time-series data to calculate statistical measures of the spectral characteristics of both the planted and harvested areas. The time-series for the planted areas spanned the period from sowing to nodulation, which corresponds to early October to early April. Similarly, the time-series for the harvested areas covered the period from sowing to maturing, or early October to mid-June. For each of the five reflectance bands and ten spectral indices, we calculated statistical characteristics, including the minimum and maximum values and the standard deviation, as well as the 15th, 50th, and 90th percentiles47,64. These statistics accurately captured the variations in the surface spectra throughout the growing season.

-

(2)

Phenological features. These included the start of the season (SOS)65, growing season length (GSL)65, and the phenological feature of winter wheat extracted from peak before winter66. To model the EVI (Enhanced Vegetation Index) time-series from October to December, we used a non-linear quadratic polynomial. The quadratic coefficient controlled both the direction and magnitude of the fitted curve. A negative coefficient indicated that the land cover type associated with the attribute was a winter crop.

-

(3)

Elevation features such as the elevation and slope12,17,24 were also used to assist the classification process.

Classification and accuracy validation

We employed a random forest (RF) algorithm in GEE to map planted and harvested areas of winter wheat. RF classifiers are ensemble classifiers that use a set of decision trees to predict classifications or regressions and have the advantage of being highly accurate, efficient, and stable. RF classifiers have also been shown to outperform other machine-learning classifiers in GEE in mapping pasture and cropland67. In this study, we specified the number of trees in the RF classifier as 500; the values of the other parameters were set to their GEE default values. To mitigate minor fluctuations in the outcome resulting from the inherent unpredictability of random forest sampling, we fixed the random seed value as 999. All other parameters were maintained at their default configurations.

The accuracy of the winter wheat identification was evaluated using two methods: (1) validation based on sample points and (2) comparison with administrative unit statistics from statistical yearbooks. To establish the confusion matrix for the winter wheat map of each province, we divided all winter wheat samples and non-winter wheat samples in a 7:3 ratio, with 30% of both the wheat and non-wheat samples allocated for accuracy validation, and the other 70% were used for training. The overall accuracy (OA) was used to evaluate the validity of the identification methods (Eq. 4). We also calculated the producer’s accuracy (PA) (Eq. 5), which indicates the proportion of samples correctly classified as belonging to the target class, as well as the user’s accuracy (UA) (Eq. 6), which indicates the number of samples classified as belonging to the target class on the classification map as a proportion of the number of samples on the ground that actually belong to that class.

Three further statistical metrics – the mean absolute error (MAE) (Eq. 7), root mean square error (RMSE) (Eq. 8), and coefficient of determination (R2) (Eq. 9) – were also employed to evaluate the classification performance.

In the above equations, n represents the number of classes (and is also the total number of rows or columns in the confusion matrix); Aii represents the number of image elements in the first row and column of the confusion matrix; and N represents the total number of real samples. Ai+ represents the total number of pixels n row i, and A+i represents the total number of pixels in column i, yi is the area identified as winter wheat belonging to the ith municipal unit, ŷ is the statistical area, and \(\bar{y}\) is the average value for the identification area.

Finally, we verified the disparity between the harvested and planted areas resulting from meteorological hazards and human-induced factors.

Data Records

Our final product, ChinaWheatMap10, is comprised of two components: ChinaWheatMap10_P, which indicates the planted area, and ChinaWheatMap10_H, which represents the harvested area. The dataset covers the years 2018 to 2022 and is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2509768468 in GeoTIFF format. A pixel value of 1 is assigned to winter wheat. The dataset employs the EPSG: 4326 (GCS_WGS_1984) spatial reference system. The maps can be visualized and analyzed using software such as ArcGIS, QGIS, or similar applications.

Technical Validation

The evaluation of the method used in this study and the maps that were produced consisted of three parts: (1) the planted area products we collected were used to validate the precision of the temporally migrated samples, (2) the planted area products we collected were used to compare to our planted area product, and (3) the overall accuracy (OA), user’s accuracy (UA), and producer’s accuracy (PA) were calculated for the annual harvest maps based on the ground validation samples.

Validation of temporally migrated winter wheat samples

We evaluated the accuracy of the temporally migrated winter wheat samples using the ChinaWheat308 and ChinaWheat1024 products. We used the 2019–2020 winter wheat samples that had been generated and applied the temporal migration method described above to obtain samples for 2021 and 2022. We then calculated the accuracy of the migrated samples for each province, as depicted in Fig. 4. Validation using the ChinaWheat10 product showed that the accuracy of the migrated samples was 97.24%, whereas the accuracy of the 2022 samples was 92.62%. Using ChinaWheat30, the accuracy of the migrated 2021 samples was 94.89%, and for the 2022 samples, it was 91.29%. For both products, most provinces had sample accuracies of above 90%, demonstrating the validity of our method. Notably, the provinces of Shandong, Henan, Hebei, Anhui, and Shaanxi had the highest accuracies for the migrated samples, with the accuracy surpassing 90% for both products. This can be attributed to the widespread cultivation and regional concentration of winter wheat on the plains in these provinces. Jiangsu was also found to have a high migration accuracy, with the ChinaWheat10 validation accuracy exceeding 90% and the ChinaWheat30 accuracy being slightly below 90%. Presumably, this discrepancy was because some of the plots in Jiangsu were narrow, meaning that the 30-m spatial resolution of the ChinaWheat30 product is not suited to the area. On the other hand, for Hubei and Shanxi, although the validation accuracies were high in 2021, these dropped to about 70% in 2022. This decrease may be attributable to increased cloud cover in these provinces in 2022 leading to limited availability of optical data and resulting in a bias in the NIRv curves that were obtained. It can be concluded that our time-migrated samples had a consistently high level of accuracy and reliability across the study area.

Validation of winter wheat planted area

The ChinaWheatMap10 product maps the winter wheat planted area for eight provinces on the Huang–Huai–Hai Plain. It has an overall accuracy of 94.51%, with a user’s accuracy of 96.60% and a producer’s accuracy of 93.03%. With the exception of Hubei and Shanxi, the accuracy metrics have values of over 90%, with Anhui province having the highest values – the overall, user’s, and producer’s accuracy are all over 97% for this province.

We compared the estimated winter wheat planted areas at the provincial level with the data reported in the statistical yearbook. The statistical yearbook listed an annual wheat cultivation area of approximately 19.5 million hectares, whereas the total area of our extracted planted areas was around 18.7 million hectares. The two sets of data were consistently in alignment, with the yearbook data slightly exceeding our estimated measurements. To conduct a comprehensive comparison between the estimated winter wheat planted area and the numbers recorded in the statistical yearbook, we computed the mean absolute error, root mean square error, and coefficient of determination at the municipal scale for the years 2018–2022. In addition, we incorporated the three winter wheat area datasets (PTDTW13, ChinaWheat308, and ChinaWheat1024) into the analysis, and the results for the above indicators are presented in Fig. 5. It can be seen that ChinaWheat30 has the highest R2 value, the smallest RMSE and MAE values, and the best consistency between the estimated values and statistical yearbook data. This can be attributed to the use of provincial-level winter wheat statistical data in the estimation of the dissimilarity thresholds8. It can also be seen that our product has the second-highest accuracy because ChinaWheatMap10 has the second highest R2 and the second lowest RMSE and MAE. Although the accuracy of ChinaWheat10, which is produced using the ATDG method, is similar to that of our product, it has a lower R2 value for the model migration approach, which results in larger RMSE and MAE values and a reduction in precision. Hence, it can be inferred that migrating the samples and subsequently plotting the planted area is more effective than directly migrating the classification model. The PTDTW results have the lowest accuracy and deviate significantly from the statistical yearbook data.

At the county level, the planted area results we extracted demonstrate good consistency with statistical data across varying area ranges (as shown in Fig. 6). The extraction accuracy is highest in counties where the planted area exceeds 40 thousand hectares. Notably, however, even in counties with smaller planted areas, less than 1 thousand hectares, the extraction accuracy remains relatively high.

The field survey samples we collected from 2018 to 2022 span multiple provinces within our study area. The average accuracy of the harvested area, as verified by these samples, is approximately 95% (as shown in Table 5), consistent with the precision confirmed by the test sample set retained during classification.

Finally, we compared the effectiveness of our winter wheat planted area maps with earlier maps in terms of the identification of major land cover types. Figure 7(A,B) display the results for areas with the built-up and water cover types, and Fig. 7(C,D) compare the results for two representative winter wheat areas. The first column shows the Sentinel-2 base map, which was used as a reference; the classification results of PTDTW, ChinaWheat30, ChinaWheat10, and ChinaWheatMap10 are shown in columns 2–5. Although the two DTW-based maps successfully identify winter wheat within the arable areas, there are instances of misclassification in areas with over land cover types. For instance, PTDTW misclassifies numerous forest pixels as winter wheat (see the second column of Fig. 7(B)), whereas ChinaWheat30 misclassifies some built-up and water areas as winter wheat; this classification is not observed in the case of ChinaWheatMap10 and ChinaWheat10. Furthermore, due to the primary data source being Landsat8, the low spatial resolution of ChinaWheat30 limits its capability to accurately distinguish neighbouring plots within the area planted with winter wheat. Furthermore, it identifies field ridges as winter wheat pixels (see the third column of Fig. 7(C)). While ChinaWheat10 exhibits excellent performance in distinguishing winter wheat from different cover types, it can suffer from overclassification and misidentify barren land without vegetation as winter wheat (as shown by the red boxes in the fourth column of Fig. 7(C,D)). In contrast, our maps exhibit minimal issues of this nature. Although these maps were constructed using a pixel-based classification approach for fragmented landscapes, our winter wheat maps exhibit promising results that effectively separates winter wheat plots, with only slight “pretzel” noise.

Comparison between PTDTW, ChinaWheat 30, ChinaWheat10, and ChinaWheatMap10 for specific areas. The first column consists of Sentinel-2 RGB imagery, which was used as a reference. In the other four columns, the areas identified as winter are highlighted in green. Parts (A) and (B) correspond to areas covered with built-up and water, and forest land cover types, respectively; parts (C) and (D) are two representative winter wheat areas.

Validation of winter wheat harvested area

Based on the results for the winter wheat planted area, we conducted mapping of the harvested area for the same eight provinces. The results indicated an overall accuracy of 96.80%, with a user’s accuracy of 97.11% and a producer’s accuracy of 94.10%. The results for the individual provinces are shown in Fig. 8(f)–(j). The average total accuracy, user’s accuracy, and producer’s accuracy for the eight provinces were determined to be 95.06%, 96.76%, and 93.68%, respectively. We compared these results with the data reported in the statistical yearbook for these provinces and found that the areas given in the yearbook were smaller than the mapped areas. Details of this comparison are shown in Fig. 8(a)–(e).

To facilitate comparison with the CROPGORIDS dataset, we aggregated both the harvest area results and the CROPGORIDS grid to a spatial resolution of 0.1° and aligned them. Using 700 randomly selected sample points, we extracted and compared the values within the corresponding pixel ranges, as shown in Fig. 9. The R² between the two datasets was 0.77, indicating a high level of agreement, while the RMSE and MAE were 1.27 and 0.76 thousand hectares, respectively.

On the Huang–Huai–Hai Plain, the wheat harvest is primarily concentrated in specific regions, namely the North China Plain (which encompasses south-central Hebei, Henan, western Shandong, northern Anhui, and Jiangsu), the Jiang–Han Plain (which covers south-central Hubei), and the Fen–Wei Plain (Fig. 10). There is also some small-scale wheat production in the hilly areas of Shandong and southern Anhui. Our analysis shows that the total harvested area is approximately 16.3 million hectares, which represents a decrease of 2.4 thousand hectares or 12.88% compared to the planted area. Multiple factors, including meteorological hazards and human influences, have contributed to this reduction in wheat production.

Maps illustrating the planted area, harvested area, and the difference between these areas for winter wheat between 2018 and 2022. The bottom graph in the third column presents the frequency of dry hot wind and the afflicted probability of waterlogging incidents from 2018 to 2022, as well as examples demonstrating the impacts caused by various hazards.

We mapped the sowed and harvested areas for winter wheat for the years 2018–2022 and the differences between these two areas (Fig. 10). These differences were then considered in relation to the most common meteorological hazards that are experienced in the study area. These hazards mainly include dry hot wind and waterlogging. Dry hot winds occur in five of the provinces, namely Henan, Hebei, Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Shandong, and waterlogging occurs mainly in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including in Hubei, Anhui, and Jiangsu (see the third column of Fig. 10). In May and June, heavy rains, gusty winds, and hailstorms can also cause damage. Pests and diseases, including powdery mildew and stripe rust, are also factors that cannot be ignored. Examples of the reduction in the number of pixels corresponding to the harvested area of winter wheat due to the above reasons are also shown in Fig. 10. During the study period, relevant incidents included the following: in 2018, Hefei City experienced severe waterlogging69 (see the third column of Fig. 10(a)); in 2019, dry hot wind affected Xinji City in Hebei Province70 (see the third column of Fig. 10(b)); in 2020, Qingdao City in Shandong Province experienced three severe wind and hailstorms (see the third column of Fig. 10(c) and https://www.cma.gov.cn/); in 2021, in Qishan County, Shaanxi Province, a large area of wheat was affected by a severe outbreak of stripe rust71 (see the third column of Fig. 10(d)); and Jingzhou City, Hubei Province, suffered from torrential rain during the wheat harvest in May 2022 (see the third column of Fig. 10(e) and http://hb.cma.gov.cn/).

As the main factors contributing to the reduction in harvested areas in the study area are waterlogging and dry hot wind, it was important to assess the afflicted probability of winter wheat suffering from waterlogging incidents and the frequency and severity of dry hot winds from 2018 to 2022. The relevant data was then classified according to the severity of the incidents (see the third column of Fig. 10), and the corresponding reduction in agricultural area was determined for each class of severity calculated, Fig. 11 illustrates the findings of this analysis. In regions with a waterlogging probability exceeding 80%, approximately 40.4% of the planted area faced potential harvesting challenges (Fig. 11(a)). For regions where this probability was within the 80–100% range, the average reduction in harvested area was approximately 204.7 thousand hectares per year. This reduction increased to an average of approximately 429.6 thousand hectares per year for areas with a waterlogging probability in the 60–80% range, 522.9 thousand hectares per year for areas in the 40–60% range, 443.4 thousand hectares per year for areas in the 20–40% range, and 101.6 thousand hectares per year for regions in the 0–20% range. Although regions with higher waterlogging probability were more likely to experience reduced harvests, the actual reduction in area was not substantial due to the lower winter wheat cultivation rates in these regions. The regions that consistently experienced dry hot winds especially the severe type contributed most to the reduction in harvestable winter wheat pixels. On average, the regions suffering from severe dry hot winds every year had an annual reduction of approximately 56.8 thousand hectares. In contrast, in regions that experienced severe dry hot wind only once, the corresponding values were 11.7 thousand hectares (Fig. 11(b)).

Human activities also contribute to the decrease in the harvested area (Fig. 12). For instance, Fig. 12(A) shows a comparison between remote sensing images acquired during the jointing and flowering stages. It can be seen that a road was constructed in the period between the two stages, resulting in a reduction in the harvested wheat area. Similarly, the demolition of a house in the area indicated in Fig. 12(B) led to damage to the adjacent winter wheat. In addition, the areas highlighted in Fig. 12(C,D) may have been used for cultivating crops other than winter wheat.

Examples of reductions in winter wheat area due to human activities. Letters A-D mark different regions where reductions have occurred. The first and second columns display the reference Sentinel-2 imagery at the jointing and flowering stages, respectively. Columns 3–5 show the planted area, harvested area, and the difference between these areas, respectively.

Code availability

The JavaScript code used to generate the maps of planted and harvested winter wheat areas is available from the figshare repository.

References

FAO Statistical Databases. FAOSTAT: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2022).

Guo, C. et al. Predicting wheat productivity: Integrating time series of vegetation indices into crop modeling via sequential assimilation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 272–273, 69–80 (2019).

China Statistics Press. National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Remotely sensed big data: evolution in model development for information extraction [point of view]. Proc. IEEE 107, 2294–2301 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Geographic information science in the era of geospatial big data: A cyberspace perspective. The Innovation 3, 100279 (2022).

Belgiu, M. & Csillik, O. Sentinel-2 cropland mapping using pixel-based and object-based time-weighted dynamic time warping analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 204, 509–523 (2018).

Csillik, O., Belgiu, M., Asner, G. P. & Kelly, M. Object-Based Time-Constrained Dynamic Time Warping Classification of Crops Using Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 11, 1257 (2019).

Dong, J. et al. Early-season mapping of winter wheat in China based on Landsat and Sentinel images. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3081–3095 (2020).

Griffiths, P., Nendel, C. & Hostert, P. Intra-annual reflectance composites from Sentinel-2 and Landsat for national-scale crop and land cover mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 220, 135–151 (2019).

Jin, Z. et al. Smallholder maize area and yield mapping at national scales with Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Environ. 228, 115–128 (2019).

Cheng, E. et al. Wheat yield estimation using remote sensing data based on machine learning approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1090970 (2022).

Huang, X., Huang, J., Li, X., Shen, Q. & Chen, Z. Early mapping of winter wheat in Henan province of China using time series of Sentinel-2 data. GIScience Remote Sens. 59, 1534–1549 (2022).

Dong, Q. et al. Mapping Winter Wheat in North China Using Sentinel 2A/B Data: A Method Based on Phenology-Time Weighted Dynamic Time Warping. Remote Sens. 12, 1274 (2020).

Yang, G. et al. AGTOC: A novel approach to winter wheat mapping by automatic generation of training samples and one-class classification on Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 102, 102446 (2021).

Zhang, H., Du, H., Zhang, C. & Zhang, L. An automated early-season method to map winter wheat using time-series Sentinel-2 data: A case study of Shandong, China. Comput. Electron. Agric. 182, 105962 (2021).

Luo, Y. et al. Accurately mapping global wheat production system using deep learning algorithms. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 110, 102823 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Early-season and refined mapping of winter wheat based on phenology algorithms - a case of Shandong, China. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1016890 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. Winter Wheat Mapping Based on Sentinel-2 Data in Heterogeneous Planting Conditions. Remote Sens. 11, 2647 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. The Accuracy of Winter Wheat Identification at Different Growth Stages Using Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 14, 893 (2022).

Zhong, L., Hu, L., Zhou, H. & Tao, X. Deep learning based winter wheat mapping using statistical data as ground references in Kansas and northern Texas, US. Remote Sens. Environ. 233, 111411 (2019).

Qi, X. et al. The 10-meter Winter Wheat Mapping in Shandong Province Using Sentinel-2 Data and Coarse Resolution Maps. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 15, 9760–9774 (2022).

Bargiel, D. A new method for crop classification combining time series of radar images and crop phenology information. Remote Sens. Environ. 198, 369–383 (2017).

Wang, S., Azzari, G. & Lobell, D. B. Crop type mapping without field-level labels: Random forest transfer and unsupervised clustering techniques. Remote Sens. Environ. 222, 303–317 (2019).

Yang, G. et al. Automated in-season mapping of winter wheat in China with training data generation and model transfer. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 202, 422–438 (2023).

Ramezan, C. A., Warner, T. A., Maxwell, A. E. & Price, B. S. Effects of Training Set Size on Supervised Machine-Learning Land-Cover Classification of Large-Area High-Resolution Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. 13, 368 (2021).

Yan, S. et al. Large-scale crop mapping from multi-source optical satellite imageries using machine learning with discrete grids. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 103, 102485 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Long-term (2013–2022) mapping of winter wheat in the North China Plain using Landsat data: classification with optimal zoning strategy. Big Earth Data 1–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/20964471.2024.2363552 (2024).

Ofori-Ampofo, S., Pelletier, C. & Lang, S. Crop Type Mapping from Optical and Radar Time Series Using Attention-Based Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 13, 4668 (2021).

Meng, S., Wang, X., Hu, X., Luo, C. & Zhong, Y. Deep learning-based crop mapping in the cloudy season using one-shot hyperspectral satellite imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 186, 106188 (2021).

d’Andrimont, R. et al. LUCAS cover photos 2006–2018 over the EU: 874 646 spatially distributed geo-tagged close-up photos with land cover and plant species label. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4463–4472 (2022).

Zhang, C., Marzougui, A. & Sankaran, S. High-resolution satellite imagery applications in crop phenotyping: An overview. Comput. Electron. Agric. 175, 105584 (2020).

Xie, B., Zhang, H. K. & Xue, J. Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Mapping Smallholder Agriculture Using High Spatial Resolution Satellite Image. Sensors 19, 2398 (2019).

Teixeira, I., Morais, R., Sousa, J. J. & Cunha, A. Deep Learning Models for the Classification of Crops in Aerial Imagery: A Review. Agriculture 13, 965 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Crop type mapping with temporal sample migration. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2023.2192881 (2023).

Wen, Y. et al. Mapping corn dynamics using limited but representative samples with adaptive strategies. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 190, 252–266 (2022).

Wang, Z., Liu, D. & Wang, M. Mapping Main Grain Crops and Change Analysis in the West Liaohe River Basin with Limited Samples Based on Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 15, 5515 (2023).

Lei, G. et al. OIC-MCE: A Practical Land Cover Mapping Approach for Limited Samples Based on Multiple Classifier Ensemble and Iterative Classification. Remote Sens. 12, 987 (2020).

Zhu, P. & Burney, J. Temperature‐driven harvest decisions amplify US winter wheat loss under climate warming. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 550–562 (2021).

Wei, D., Gephart, J. A., Iizumi, T., Ramankutty, N. & Davis, K. F. Key role of planted and harvested area fluctuations in US crop production shocks. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1177–1185 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Spatiotemporal Changes of Winter Wheat Planted and Harvested Areas, Photosynthesis and Grain Production in the Contiguous United States from 2008–2018. Remote Sens. 13, 1735 (2021).

Lobell, D. B. et al. Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation Needs for Food Security in 2030. Science 319, 607–610 (2008).

Stuecker, M. F., Tigchelaar, M. & Kantar, M. B. Climate variability impacts on rice production in the Philippines. PLOS ONE 13, e0201426 (2018).

Boryan, C., Yang, Z., Mueller, R. & Craig, M. Monitoring US agriculture: the US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Cropland Data Layer Program. Geocarto Int. 26, 341–358 (2011).

Fisette, T. et al. AAFC annual crop inventory. in 2013 Second International Conference on Agro-Geoinformatics (Agro-Geoinformatics) 270–274, https://doi.org/10.1109/Argo-Geoinformatics.2013.6621920 (IEEE, Fairfax, VA, USA, 2013).

Lesiv, M. et al. Estimating the global distribution of field size using crowdsourcing. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 174–186 (2019).

Song, C., Woodcock, C. E., Seto, K. C., Lenney, M. P. & Macomber, S. A. Classification and Change Detection Using Landsat TM Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 75, 230–244 (2001).

You, N. et al. The 10-m crop type maps in Northeast China during 2017–2019. Sci. Data 8, 41 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Mapping annual 10-m maize cropland changes in China during 2017–2021. Sci. Data 10, 765 (2023).

Zanaga, D. et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2021 v200. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7254221 (2022).

Copernicus Climate Change Service. ERA5-Land hourly data from 2001 to present. ECMWF https://doi.org/10.24381/CDS.E2161BAC (2019).

China Meteorological Administration. Meteorological Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Grade of Waterlogging for Winter Wheat and Rape (QX/T 107-2009) (2009).

Wang, S., Rao, Y., Chen, J., Liu, L. & Wang, W. Adopting “Difference-in-Differences” Method to Monitor Crop Response to Agrometeorological Hazards with Satellite Data: A Case Study of Dry-Hot Wind. Remote Sens. 13, 482 (2021).

China Meteorological Administration. Meteorological Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Disaster Grade of Dry-Hot Wind for Wheat (QX/T 82-2019) (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Winter Wheat Waterlogging in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River, China. Adv. Meteorol. 2018, 1–11 (2018).

Tang, F. H. M. et al. CROPGRIDS: a global geo-referenced dataset of 173 crops. Sci. Data 11, 413 (2024).

Qiu, B. et al. Maps of cropping patterns in China during 2015–2021. Sci. Data 9, 479 (2022).

Wa, W., Z. X. & Li, F. Development and Application of Sentinel-2 Canopy Chlorophyll Content (CCC) Validation Dataset of Winter Wheat in Yucheng, Shandong of China https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2021.02.01.

Limei, W., Guowang, J., Xin, X., Ke, W. & Qihao, H. Winter wheat mapping in land fragmentation areas using remote sensing data. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. Trans. CSAE 38, 190–198 (2022).

Eltazarov, S., Bobojonov, I., Kuhn, L. & Glauben, T. The role of crop classification in detecting wheat yield variation for index-based agricultural insurance in arid and semiarid environments. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 18, 100250 (2023).

Torres-Sánchez, J., Peña, J. M., De Castro, A. I. & López-Granados, F. Multi-temporal mapping of the vegetation fraction in early-season wheat fields using images from UAV. Comput. Electron. Agric. 103, 104–113 (2014).

Tian, J. et al. Investigating the urban-induced microclimate effects on winter wheat spring phenology using Sentinel-2 time series. Agric. For. Meteorol. 294, 108153 (2020).

Xing, H., Chen, B. & Lu, M. A Sub-Seasonal Crop Information Identification Framework for Crop Rotation Mapping in Smallholder Farming Areas with Time Series Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 14, 6280 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Higher Sensitivity of NIRv,Rad in Detecting Net Primary Productivity of C4 Than that of C3: Evidence from Ground Measurements of Wheat and Maize. Remote Sens. 15, 1133 (2023).

Xuan, F. et al. Mapping crop type in Northeast China during 2013–2021 using automatic sampling and tile-based image classification. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 117, 103178 (2023).

Pan, L., Xia, H., Zhao, X., Guo, Y. & Qin, Y. Mapping Winter Crops Using a Phenology Algorithm, Time-Series Sentinel-2 and Landsat-7/8 Images, and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 13, 2510 (2021).

Tao, J., Wu, W., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y. & Jiang, Y. Mapping winter wheat using phenological feature of peak before winter on the North China Plain based on time-series MODIS data. J. Integr. Agric. 16, 348–359 (2017).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 114, 24–31 (2016).

Hu, J. et al. 10m Winter Wheat Harvested Area and Planted Area Distribution Map of China for Five Years (2018-2022) figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.25097684 (2024).

Ding, J. et al. Effects of waterlogging on grain yield and associated traits of historic wheat cultivars in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, China. Field Crops Res. 246, 107695 (2020).

Kang, X. et al. Study on the different responses of different winter wheat cultivars to dry hot wind. PLOS ONE 17, e0274118 (2022).

Zhao, M., Dong, Y., Huang, W., Ruan, C. & Guo, J. Regional-Scale Monitoring of Wheat Stripe Rust Using Remote Sensing and Geographical Detectors. Remote Sens. 15, 4631 (2023).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 195–213 (2002).

Zeng, Y. et al. A practical approach for estimating the escape ratio of near-infrared solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence. Remote Sens. Environ. 232, 111209 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. A snow-free vegetation index for improved monitoring of vegetation spring green-up date in deciduous ecosystems. Remote Sens. Environ. 196, 1–12 (2017).

Vincini, M., Frazzi, E. & D’Alessio, P. A broad-band leaf chlorophyll vegetation index at the canopy scale. Precis. Agric. 9, 303–319 (2008).

Huete, A. R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 25, 295–309 (1988).

Xiao, X. Modeling gross primary production of temperate deciduous broadleaf forest using satellite images and climate data. Remote Sens. Environ. 91, 256–270 (2004).

Kataoka, T., Kaneko, T., Okamoto, H. & Hata, S. Crop growth estimation system using machine vision. in Proceedings 2003 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM 2003) vol. 2 b1079–b1083 (IEEE, Kobe, Japan, 2003).

Woebbecke, D. M., Meyer, G. E., Von Bargen, K. & Mortensen, D. A. Color indices for weed identification under various soil, residue, and lighting conditions. Trans. ASAE 38, 259–269 (1995).

Gitelson, A. A., Kaufman, Y. J., Stark, R. & Rundquist, D. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 80, 76–87 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42030111) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB3900503).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K.H., B.Zhang and D.P. designed the research and developed the methodology; J.K.H., E.C. and S.L. developed the workflow and constructed the dataset; J.X.H., W.Z., B.Zhao, Y. Li, Z.L., S.Y., Y.T. and Y.Lv collected the datasets; J.K.H. drafted the manuscript; and B.Zhang and D.P. edited and revised the paper. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, provided in-depth advice, and commented on and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Zhang, B., Peng, D. et al. Mapping 10-m harvested area in the major winter wheat-producing regions of China from 2018 to 2022. Sci Data 11, 1038 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03867-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03867-z