Abstract

We present the CREATTIVE3D dataset of human interaction and navigation at road crossings in virtual reality. The dataset has three main breakthroughs: (1) it is the largest dataset of human motion in fully-annotated scenarios (40 hours, 2.6 million poses), (2) it is captured in dynamic 3D scenes with multivariate – gaze, physiology, and motion – data, and (3) it investigates the impact of simulated low-vision conditions using dynamic eye tracking under real walking and simulated walking conditions. Extensive effort has been made to ensure the transparency, usability, and reproducibility of the study and collected data, even under extremely complex study conditions involving 6 degrees of freedom interactions, and multiple sensors. We believe this will allow studies using the same or similar protocols to be comparable to existing study results, and allow a much more fine-grained analysis of individual nuances of user behavior across datasets or study designs. This is what we call a living contextual dataset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

In a joint effort of computer science, cognitive psychology, and clinical practitioners, we aim to analyze the impact that simulated low-vision conditions have on user behavior when navigating complex road crossing scenes: a common daily situation where the difficulty to access and process visual information (e.g., traffic lights, approaching cars) in a timely fashion can lead to serious consequences on a person’s safety and well-being. As a secondary objective, we also aim to investigate the potential role virtual reality (VR) could play in rehabilitation and training protocols for low-vision patients.

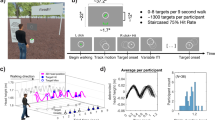

The experimental protocol consists of three stages: (1) pre-experience preparation including signing the informed consent, a survey and equipping the headset and sensors (2) the experimental study comprised of four conditions: with and without simulated low vision combined with simulated or real walking, six scenarios per condition (in addition to a calibration scenario) with varying interaction complexity and stress levels, two perspective taking tasks in the middle and at the end of a condition, and a short post-condition survey after each condition, and (3) a post-study survey and removal of equipment. The condition and scenario sequence were pseudo-randomized. The entire study lasted roughly two hours.

During the study phase, we fit users with (1) an HTC Vive Pro Eye headset that recorded gaze, head motion, and user interaction logs, (2) an XSens Awinda Starter motion capture system, and (3) Shimmer GSR+ sensors with skin conductance and heart rate capture.

Comparison with similar datasets

A large number of datasets exist for human motion and behavior capture in context. Here we provide a brief comparison in Table 1, focusing on those that have motion capture in context. The most similar dataset to ours is the CIRCLE dataset1 published very recently, which involved around 10 hours of human motion and egocentric data captured in VR scenes using a 12 Vicon camera setup. The actions concern reaching tasks in scenes annotated with the initial state and goals. For full-body motion capture, the Human3.6m2 dataset is the most widely used, and up until recently the largest, featuring 3.6 million poses with RGB camera filming as well as actor lidar scans. However, object interactions are not tracked. The focus of Human3.6m to provide a wide variety of human motions by professional actors. The GIMO3 and EgoBody4 datasets on the other hand combine motion capture and augmented reality headsets – the Hololens – to capture gaze and motion in context. The physical environments are scanned as 3D meshes and calibrated to have the motion and scene in the same coordinate system. These recent datasets highlight the important role that virtual environments and extended reality (virtual and augmented reality) technologies are already playing for in-context human behavior capture and understanding.

There are a number of datasets that are also worth noting, but not included in the comparison due to the very different nature of their data. The GTA-IM dataset5 provides synthetic animations generated using the Grand Theft Auto game engine. With the large variety of scenes, character models, and animation styles, the dataset demonstrates the strong potential 3D animations can play in generating realistic simulations for various learning tasks. Another dataset, GazeBaseVR6 focuses on gaze tracking using VR headsets. Gaze behavior is collected and analyzed for 407 participants on 5 standardized viewing tasks. However, while a headset is employed, the stimuli are 2D.

Contribution

The CREATTIVE3D dataset is for now the largest dataset (in terms of frames, number of subjects, and duration) on human motion in fully-annotated contexts. To our knowledge it is the only one conducted in dynamic and interactive virtual environments, with the rich multivariate indices of behavior as mentioned above. The contribution is twofold. First, we underline the advantages of virtual reality for the study of behavior in context, such as with simulated low vision. Second, we investigate the feasibility of the concept of a living contextual dataset: the collection, processing, and analysis of datasets of living behavior in various contexts which aims to be fully reproducible such that future studies using the same protocol can compare to existing results with sufficient confidence. Moreover, the openness of the protocol to different modalities of data that can be correctly synchronized allows a fine-grained analysis of individual nuances of user behavior across datasets or study designs. We believe living contextual datasets can be a motor for research questions across multiple domains of modeling, human computer interactions, cognitive science, and society.

This paper presents the full dataset of the study conducted with 40 participants using the protocol described in our previous work7 (our previous publication only involves 17 participants without making the dataset available). In addition, we provide detailed technical validation for the study design (pilot studies), data issues, processing conducted to synchronize data, and internal questionnaire consistency. Five usage notes along with source code on the dataframe, statistical modeling, fine-grained user understanding, machine learning, and data visualization were designed to illustrate the usage scenarios of the dataset.

Methods

The study was approved by the Université Côte d’Azur ethics committee (No 2022-057). Participants provided consent to the open publication of data under the principles that the data is anonymous on collection (data is characterized only with a user ID that is not linked to the user’s name), and no identifying information nor health/medical data was collected. During the study, multiple modalities of data were collected, the setup of which we describe below. Additional details of the study design and system can be found in our previous work7,8.

Scenarios

In order to build a dataset composed of a large range of user behaviors, six scenarios were designed around two axes of metrics we wanted to observe on the user experience :

-

Cognitive load axis affected by changing the amount of road lanes and cars driving in the VR environment, ranging from 2 lanes with a car on each, to 1 lane with no car at all.

-

Interaction complexity axis affected by changing the amount and the type of interactions asked to the player during the scenario, ranging from only one task asking to pick up one object, to multiple tasks of object interaction, object pick up, object placement, traffic light observation.

The scenarios were implemented using the GUsT-3D software framework8, which allows the creation of scenes through dragging and dropping assets in place. Each object can be annotated with a customized ontology, including the name of the object and its type (e.g., “movable”, “container”, “navigable surface”. The software is open source and can be requested (ref. Code Availability).

Walking conditions

In each scenario, users did a selection of activities from 13 possibilities: “Take the trash bag”, “Find the key”, “Interact with the door using the key”, “Go outside”, “Press traffic button”, “Wait for green light”, “Cross the street” (in two different directions), “Put the trash bag in the trash can”, “Return to house”, “Take the box”, “Put the box on the table”, “Put the box in the trash can”. The number and choice of activities depended on the cognitive load and interaction complexity axes of the scenario. Each scenario was performed under two movement conditions:

-

Real walking (RW): the most natural mode of movement in virtual reality. The user walks physically with a 1:1 ratio between the real and virtual distance in the 10 meters by 4 meters tracked space.

-

Simulated walking (SW): motivated by potential at-home rehabilitation usage where space is limited. The user moves in the direction of the controller by pressing the trigger, leaving the user’s head free to explore the environment. The user camera advances at a speed of 0.9 meters/second based on existing studies of preferred walking speeds in VR9. The user can turn on the spot.

Simulating low vision

One of the principal goals of this study was to investigate how low-vision conditions could impact user behavior. Our study targets age-related macular degeneration (a.k.a. AMD) that can result in a scotoma – an area of decreased or lost visual acuity in the center of the visual field – which strongly impacts everyday activities of patients. We take advantage of integrated eye tracking technologies in VR headsets to design a virtual scotoma. Based on existing clinical studies10, we create a virtual black dot measuring 10° visually, as shown in Fig. 1(b) that follows the cyclopean eye vector (i.e., the combined left and right gaze vectors) from the eye tracker.

Overview of the study workflow and simulated low-vision condition with a virtual scotoma. (Figure orignally presented in Robert et al.7): (a) study overall workflow with four conditions and six scenarios per condition (in addition to a calibration scene), (b) participant view of the simulated scotoma – a region at the center of the visual field with no visual information – following the gaze of the participant. The scotoma represents 10° in diameter of the foveal field of view, based on clinical studies10.

Study

With the above setup, the experimental protocol is presented in Fig. 1(a) with each user passing a total of 24 scenarios: six different scenes with a combination of walking (real / simulated) and visual (normal / simulated low vision) conditions. We recruited 40 participants (20 women and 20 men) through 5 university and laboratory mailing lists. Participants needed to have normal or corrected to normal binocular vision.

The participants upon recruitment were sent a message with their booked time slot, guidelines to wear fitting or light attire, as well as the informed consent. The study lasted approximately two hours long, and was conducted in either English or French at the preference of the participant. 20 euros compensation was given in the form of a check at the end of the study. At the study time, the participants were first invited to sign the informed consent, answer the pre-experience survey, and fitted with the equipment. Participants were informed of the risks of nausea, fatigue, and motion sickness, and were encouraged to ask for a pause or request ending the study if they felt discomfort, which would not impact their compensation. Snacks and drinks were made available to the participant and offered by the experimenters between conditions and at the end of the study.

During the study, two experimenters were always present to help arrange the equipment, answer questions, and provide the participant with guidance in using the equipment. When the participant is walking with the headset on, one of the experimenters is always focused on them to notice any loose equipment, check for risk of collision or falling. Inflatable mattresses surround the navigation zone to prevent any collision with walls or equipment.

At the beginning of each condition, a pilot scenario (numbered 0) was presented to the participant to help them discover the environment, familiarize with the interactive and navigational modalities in order to lower the learning curve. This scenario is also used to calibrate the headset height. The calibration was designed after numerous pilot tests that showed a miscalculation of headset height using the Vive’s integrated sensors, and also encouraged users to maintain a more upright pose to avoid instability.

Following the pilot scenario, each participant then completed six scenarios under the four conditions, for a total of 24 scenarios. The sequence of the conditions and the sequence of scenarios under each condition were pseudo-randomized using the Latin Square attribution to avoid the effect of repetitive learning and fatigue on specific conditions.

At the end of every three scenarios, participants also performed a pointing task11, to quantify the level of presence the user experiences in the environment. During this test, the virtual environment is hidden, and the participant is asked to point with their arm in the direction of a target designated by the audio instruction, usually a salient object with which they interacted during the scenario such as a trash can or the initial location of the key or garbage bag. A strong deviation between the participant’s arm and the correct direction would indicate a higher level of spatial disorientation, and likely a reduced level of presence.

The post-condition survey was presented to the participant after each condition, which also served as a pause period, to re-calibrate motion tracking, eye tracking, physiological sensors, and give the participants the opportunity to ask any questions and declare sensations of fatigue or nausea. At the end of all conditions, the equipment was removed and the final post-experience survey was presented to the participant.

Materials and data collection

The study involved various equipment for running the scenarios and capturing user behavior including:

Eye tracking headset with eye tracking being a strong prerequisite for this study, in order to place the virtual scotoma in real time based on the gaze position for the simulated low-vision condition. We chose the HTC Vive Pro Eye, which includes by default eye and head tracking functionality, with SteamVR for the VR environment configuration. We defined the size of the environment based on standard road crossings. The minimum required width of a car lane is 3.5 m, and the minimum width of the pedestrian crosswalk was 2.5 m with the standard being 4–6 m. We included one meter of pedestrian crossing on each side of a two lane road, and some margin on the sides of the crosswalk to ensure safety. In total, the required navigation space for this study is 10 m × 4 m, delimited in Fig. 2. We used thus used an add-on wireless module to enable such a large navigation space.

The environment used for the experience measures 4 by 10 meters in navigation area is delimited by four base stations, one at each corner, and aligned with the virtual environment. Mattresses surround the are for security. (Figure orignally presented in Robert et al.7).

Motion capture which provides very rich metrics such as step length or body inclination of participants to evaluate how confident they feel walking in a VR environment. It can also be used such as to validate the accuracy of the pointing task. The MVN Awinda system was chosen in the end due to its resilience towards magnetic interference as well as the precision of the captured data. The Xsens MVN 2022 software was used to calibrate and record the data, and the Xsens MVN motion cloud was used to convert the records in formats .mvnx and .bvh for later analysis. Users were generally very comfortable with the motion capture equipment, reporting little to no interference with the task in the survey after each condition (from questionnaires, average score of 1.175 over all conditions, 1 indicating no interference and 5 indicating strong interference).

Physiology sensors that can capture the skin conductance (a.k.a. GSR or galvanic skin response) and heart rate, which can be used to measure the level of arousal of the user or the level of activity they are experiencing. The GSR Shimmer solution was chosen in the end for its higher data rate (15Hz re-sampled at 100Hz). The Consensys software was used for the configuration and initial data processing and export. The placement of the sensors was tested repeatedly before the study to find the configuration that interfered least with the task, and also prevented impact of interactions such as pushing the buttons on the controller. In the end, the GSR sensor was placed on the finger roots of the non-dominant hand, and the heart rate sensor on the tip of the thumb. We instructed users on how to hold the controller as to avoid pushing on the sensors. In the end, users did not report significant discomfort when doing interactions with the hand equipped with sensors (from questionnaires, average score of 1.538 over all conditions, 1 indicating no interference and 5 indicating strong interference).

Surveys that we coupled the sensor and log data, proposed during a co-design session with all project members. The surveys were administered at three time points: pre-experience (T1), post-condition (i.e., administered after each of the four conditions), and post-experience (T2). The pre-experience survey comprised: study information (i.e., user ID, study language), demographics (i.e., gender, age group), previous experience with VR and video games, experiences of motion sickness (i.e., usage frequency, open question about identified situations), technology acceptability based on the UTAUT2 model (i.e., performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, habit, and behavioral intention) where the term “mobile Internet” from the original English version and the term “ICT for Health” from the French version were replaced by “virtual reality”12,13. The post-condition survey comprised: condition information (i.e., real walk without scotoma, real walk with scotoma, simulated walk without scotoma, simulated walk with scotoma), the NASA task load index14 (i.e., mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, frustration), emotion (i.e., positivity and intensity), cybersickness (i.e., from the simulator sickness questionnaire15 two items were selected per dimension: oculomotor-related, disorientation-related, nausea), perception of the experience (7 items created based on the experimental conditions), difficulties encountered during the task and global feedback (open question). The post-experience survey comprised: four items from the presence questionnaire (Witmer & Singer16), emotional state (SAM17), and technology acceptability (as measured in T1). The full list of items included in the surveys is listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Data format and machines

All data modalities were labeled with Unix timestamps (except for the surveys). The system logs, gaze plus head tracking were done on a Windows 10 desktop machine with GTX 3080 graphics card while the remaining data – motion capture, physiological sensors, and survey – were collected on a laptop also with a GTX 3080 graphics card. Using the head data on the desktop machine and the motion data with head coordinates on the laptop, we are then able to synchronize the two data streams, as will be described in the next section.

Data Records

The dataset is made available on Zenodo (no. 8269108)18. This paper describes version 4 of the dataset. Table 4 summarizes all the data modalities, the capture equipment and/or software, and data characteristics. The data package is contained in a single repository with documentation, tools, a number of usage examples, and data of 40 users. The file hierarchy of our dataset is shown in Fig. 3. The folder and file names under each user use the following labels to indicate the user, condition, and scenes.

-

User ID: represented as UX for user X. The IDs are randomly generated and in no particular order

-

Condition: Represented by four characters. The first pair RW or SW represent the walking condition (R)eal or (S)imulated. The second pair NV or LV indicate the visual condition (N)ormal or (L)ow vision.

-

Scenarios: Represented by four characters. The first pair SI or CI represent simple or complex interaction. The second pair indicate the number of moving vehicles in the scene (0V, 1V, or 2V)

The dataset contains condition and scene segmented data for each modality, as well as processed files for the motion data which required non-trivial effort to ensure spatial temporal synchronization (see Technical Validation section). For each scene, all modalities are combined and then resampled at 125 Hz into the dataframe125Hz.csv file, which we use here to illustrate the contents of the dataset. The columns in this combined dataframe are:

-

1.

TimeStamp: in the format of YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS.SSS

-

2.

Physiological data - EDA, HR: EDA in microsiemens (μS) heart rate in millivolts (mV)

-

3.

Log - position, rotation: in cartesian coordinates (x, y, z)

-

4.

Log - item, localisation, lookedAtItemName, centerViewItemName, centerViewItemRange, inViewItems: the item relevant to the task, the name of the location where the user is (e.g., house, sidewalk, crossing), the item the user gaze is directed at, the item the center of the visual field is directed at, the distance of the item in the center of the visual field (‘Near’ =< 1m or ‘Far’ > 1m), all objects in the user’s field of vision

-

5.

Log - currentTask: the current task the user is assigned

-

6.

Log - light, honk, button: color of the traffic light (red, orange, green), whether a car is animated, whether the button is available for interaction

-

7.

Log - carPosition, objectPosition: position of the car and the current task object in cartesian coordinates (x, y, z)

-

8.

Gaze - PORcentroid, PORorigin: the point of regard centroid (intersection of the gaze vector with the scene) and gaze vector origin in cartesian coordinates (x, y, z)

-

9.

Motion - MotionPos, MotionRot: The (x, y, z) position and rotation of 28 joint positions: Hips, Chest, Chest2, Chest3, Chest4, Neck, Head, HeadEnd, RightCollar, RightShoulder, RightElbow, RightWrist, RightWristEnd, LeftCollar, LeftShoulder, LeftElbow, LeftWrist, LeftWristEnd, RightHip, RightKnee, RightAnkle, RightToe, RightToeEnd, LeftHip, LeftKnee, LeftAnkle, LeftToe, LeftToeEnd

The dataframe.csv and dataframe125Hz.csv files serve as the entry point to using the dataset. However, there is also additional and rich data in individual modality files for logs (LogI and LogP) and gaze. Notably, the gaze.json files provide in addition separate left right eye gaze vectors, pupil diameter, eye openness percentage, and data validation provided by the headset eye tracker library.

Technical Validation

In order to ensure high data quality, multiple validations were put in place, including ten pilot runs preceding the actual study, detailed list of data issues, conducting data synchronization, and verifying the internal consistency of the questionnaires used, measured by Cronbach’s alpha19. We detail each of these validations below.

Pilot studies

10 pilot studies were carried out (four women and six men) from researchers and students in the project, from diverse backgrounds of computer science, cognitive science, neuroscience, and sport science. These pilot studies were repeated over a two month period involving iterative improvements to the study, refining of the protocol and surveys, and finally an all-hands co-design session with project members in December 2022 to validate and approve the final version of the study before the official launch in January 2023.

Data issues and transparency

Despite the protocol devised and iterative testing, technical issues can and do occur in complex studies such as the one we carried out, due to accidental manipulations on the experimenter’s side, hardware crashes, issues in proprietary software, latency, and individual difficulties for participants – most of which are normal and outside of the control of the study design.

With the objective of being full transparent on the data, we report all the incidents in the production process in a structured way. Specifically, we provide in the data the validation.csv file which gives a comprehensive list of various data issues, and their impact. The partial example of a row is shown in Table 5. An empty cell indicates no issues were observed. An X indicates an observed issue at a global level (e.g., incomplete questionnaires due to crash in survey server), or if only a specific number of scenes are impacted, the impacted condition and scene ID are provided.

Out of the data on 960 scenarios (24 per participant), we observed the following more critical issues that render one datatype unusable for a single scenario of a participant:

-

Gaze: missing eye or head data (5 scenarios), inconsistent head coordinates (1 scenario) and timesync (6 scenarios).

-

Questionnaire: missing questionnaires in the post-experience survey due to network problems (8 participants)

-

GUsT-3D logs: missing or irregular files (2 scenarios and all data for 2 participants)

-

Physiology: oversampling (1 participant), heart rate data not dependable

The missing timesync information can be corrected by applying an average delta of 28000 (28 ms) which will ensure data synchronization with an accuracy of within 6 ms (delta ranged between 22000 and 34000).

Hardware crashes also occurred for seven participants due to the wireless module, impacting maximum one scenario for the participant, mostly at the beginning of the study. The scenario was re-run after a hardware restart and the study continued without further issues.

Temporal and spatial synchronization

As the different modalities of the data were collected through dedicated applications on two separate machines, with different Unix timestamps and 3D axis referential, an important step in pre-processing is data synchronization. This involves temporal synchronization for all modalities of the data, and spatial synchronization of the motion data into the 3D scene referential. The presence of head position and rotation data on both machines – head tracking from the HTC Vive Pro Eye headset on one (pH ∈ R3, rH ∈ R3), and head point motion capture on the other (pM ∈ R3, rM ∈ R3)– provides us with a robust means to synchronize the various data streams on the two machines.

To establish temporal synchronization, it becomes imperative to calculate a scalar value that encapsulates this temporal alignment. To achieve this, we employ the computation of velocity, and acceleration magnitude, which characterizes the head’s motion within three-dimensional space. The magnitude provides a scalar value describing the head’s speed, regardless of its direction.

We first resample pH to 60Hz, aligned to pM sampling rate, then take the derivative of the positions to calculate the velocity \(| \overrightarrow{v}({t}_{i})| \) for the time point ti using the Euler distance divided by the frame time (ti+1 − ti) ≈ 16, 67ms:

However, the magnitude of velocity exhibits significant noise, particularly from the HTC (vH), which exhibits highly variable and peaky signal characteristics. To mitigate this issue, we employ a two-step approach: compute the 95th percentile of vH, followed by the application of a Gaussian filter to both velocities vH and motion capture one vM. The Gaussian filter smooth out short-term fluctuations and highlight long-term trends, enhancing the velocity quality. Gaussian filter is based on the Gaussian kernel, defined as:

where t is the time and σ is the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution. The Gaussian kernel values are computed for each of the discrete time velocity values using the formula mentioned above. We then convolve the velocity data with the Gaussian kernel, using a discrete convolution operation to apply the Gaussian filter to the velocity profile.

To enhance the smoothness of the head’s velocity profile, we aimed for a continuous and seamless motion without sudden changes within a 2-second window, equivalent to 120 frames of our data. To achieve a more refined and localized smoothing effect, we conducted experiments using different kernel sizes, characterized by the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), ranging from 10 to 120 frames, roughly 2.4 times the standard deviation (σ). Based on the observed performance we determined that a FWHM of 94 frames (σ ≈ 40) effectively regulates the level of smoothing for our velocity data preserving essential movement patterns. In addition, the application of Gaussian smoothing to the velocity data prior to derivative computation enhances the reliability of our acceleration estimates, as shown in Fig. 4.

Once we have the smoothed velocity data (\({v}_{{H}_{s}}\), \({v}_{{M}_{s}}\)), we compute the acceleration magnitude (aH, aM) in a similar manner as a derivative of v. Similar to our approach for velocity, we applied a Gaussian filter to the accelerations using a FWHM of 94 frames, resulting in smoothed acceleration data denoted as (\({a}_{{H}_{s}}\), \({a}_{{M}_{s}}\)). To achieve temporal synchronization, we employ cross-correlation, which allows us to find the time shift or lag that aligns two datastreams in time. In this context, we work with two sets of data, namely (\({v}_{{H}_{s}}\), \({v}_{{M}_{s}}\)) for velocities, and (\({a}_{{H}_{s}}\), \({a}_{{M}_{s}}\)) for accelerations of to the head. As depicted in Fig. 5(a), higher correlation values are observed with the acceleration data. Consequently, we have elected to use acceleration as our reference for temporal synchronization and lag determination. Each scenario was synchronized individually, exclusively under real walking conditions. Subsequently, to establish a robust measure of time lag for each subject, we computed the median of all lags obtained from conditions 1 and 3, encompassing the six scenarios within each condition.

We validate the temporal and spatial synchronization of the two head data streams: (a) shows the cross-correlation values for each scenario before and after synchronization, and (b) is the head position for one scenario before (left) spatial synchronization and after (right). HTC and Motion Capture Data Represented as pH and pM respectively.

To verify the accuracy of temporal synchronization processes, we conducted correlation analyses for each scenario in all the subjects. Our results consistently yielded correlation coefficients exceeding 0.8 in the majority of cases, indicating robust temporal alignment of our data. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that certain exceptional cases exhibited lower correlation values. These anomalies can be attributed to data inconsistencies, particularly in instances involving data collection from HTC devices.

Following temporal synchronization, the next step involves addressing spatial synchronization. This entails the computation of a transformation matrix. To align the two sets of 3D points, denoted as pH and pM, representing the positions of the Head obtained from HTC and motion capture, respectively, we employ Procrustes analysis20. This method facilitates the determination of the optimal rigid transformation between the point set pH (referred to as set A) and point set pM (referred to as set B). As shown in Equations (2–6): Set A with n points: {A1, A2, …, An}, each represented as (xi, yi, zi) and Set B with m points: {B1, B2, …, Bm}, each represented as (xi, yi, zi). We (1) compute the centroids for both sets, (2) center both sets by subtracting their respective centroids, (3) compute the covariance matrix H, (4) perform Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on matrix H to derive matrices U, S, and V and obtain the rotation matrix R, (5) compute the translation vector T, and (6) with the derived transformation matrix R and translation vector T, align set A with set B.

Figure 5(b) presents the outcomes of the spatial synchronization process. This is evident after the application of the transformation matrix to the motion capture head data denoted as pM. We provide in our dataset the spatial_sync. py script that calculates the transformation matrix transf. json from the motion_pos. csv and por. json file that can be applied to the motion. bvh files for visualization. The motion_pos. csv, motion_rot. csv, and matrix. json are the standard input for the GIMO3 transformer-based architecture.

Internal consistency of the questionnaires used

The calculation of Cronbach’s alphas was not dissociated between French and English versions regarding the low number of participants in each group (i.e., 15 surveys completed in English and 25 surveys completed in French). Descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alphas of the UTAUT2 and NASA TLX questionnaires are presented in Table 6. The Cronbach’s alphas of the UTAUT2 subscales were satisfactory19, except for the “facilitating conditions” subscale post-experience, which was below the recommended values and should be used with caution in future analyses. The Cronbach’s alphas of the NASA Task Load Index were acceptable19.

Usage Notes

Multivariate dataframe

We provide with the source code the script ex_dataframe. py that facilitates the generation of a dataframe with the multivariate gaze, motion, emotion, and user log data for each participant. The resulting dataframe can then be used as input for data visualization, statistical modeling, machine learning, and other applications. A number of these applications are described in more details below.

Statistical modeling

Beyond calculating the means of various metrics on various study conditions, we can establish models that measure the significance of various factors in our study design. Using the example of motion, suppose we would like to investigate whether the walking condition (real or simulated) impacts various gaze behaviors statistics including average fixation duration (AFD) in milliseconds and percentage of points of regard classified as fixations. We first calculate fixations using a classical I-VT algorithm21 with a velocity threshold of 120. We apply a mixed linear model of the real and virtual walking with the formulation AFD ~ scotoma + walk + complexity + interactions + (1|participant) which models participant as a random effect and the remaining factors as fixed effects. We did find that there is a significant impact of the walking condition on AFD, with globally longer fixations occurring under the simulated walking condition, while no significance was found between the normal and simulated scotoma conditions. The whisker plots in Fig. 6(a) show the distribution of fixation duration for the two walking and scotoma conditions, as well as a validation with a Q-Q plot in Fig. 6(b) showing that our model seems to correctly fit the shape of our data distribution. This finding could merit further attention on investigating user attention and its relation to training or rehabilitation efficacy in VR when space is limited, such as when one must replace real navigation modalities with proxies such as joysticks.

We used a mixed linear model on the residuals of the real and virtual walking on average fixation duration (AFD) and scotoma conditions with the formulation AFD ~ scotoma + walk + complexity + interactions + (1|participant). (a) Shows the whisker plots of the real and simulated walking conditions (blue and orange respectively) with and without the scotoma, and (b) is the Q-Q plot of the residual for the best model selected.

Fine-grained user understanding

The rich recorded context allows us to have a fine-grained view of the user’s current state, both from symbolic and continuous data. We take the example of electrodermal activity (EDA, a.k.a. skin conductance), captured using the Shimmer GSR+ module. Using NeuroKit222 we can process the EDA levels to separate the phasic and tonic components: the former is fast-changing and stimulus dependent while the latter is slower to evolve and more continuous. In Fig. 7 we show a graph of the evolution of the user’s raw EDA and the phasic and tonic components throughout a single scenario. The example script to generate this graph ex_EDA. py is included in this package.

Example evolution of the tonic component for EDA for one user under real walking and normal vision condition with task boundaries indicated by the colored lines. We see a small leap around the moment a car honks at the user for jaywalking. (Figure orignally presented in Robert et al.7).

Machine learning

The calculated dataframe from ex_dataframe. ipynb contains the synchronized, multivariate, spatial-temporal data for each user at 125 Hz, saved in a file UserID_condition_scenario_dataframe125Hz. csv. This is naturally a time series that can be used for various machine learning tasks, including:

-

Classification: binary classification such as between users of two modalities of walking (real or simulated) or presence of (virtual) visual impairment, and multi-class classification such as the current task

-

Time series forecasting: such as trajectory and motion prediction, or evolution of physiological arousal

-

Salience prediction: such as accumulated the saliency map of gaze in the 3D scene

The dataset introduces additional challenges to machine learning methodologies, most notably where blending structured and unstructured data is concerned. For example, we can investigate approaches that blend the structured contextual logs of interactions and scene entities, with the unstructured trajectory and physiological data. We provide an example use case in a model for human trajectory prediction23. We use a multimodal transformer that takes as input the human trajectory, scene point cloud, and scene context data. The code for this usage note is made available on gitlab (https://gitlab.inria.fr/ffrancog/creattive3d-divr-model).

Data visualization

Mobility data is intrinsically spatio-temporal, describing the movement of individuals over space and time through multidimensional information. Visualizing the numerous dimensions of such data without compromising clarity or overwhelming the user’s field of view, and offering freedom of exploration with natural gestures is an ongoing challenge. The conception of visualization techniques for spatial-temporal data must consider the natural properties of the data, e.g., the geographical position of locations and ordering of time units, while conveying the underlying dynamicity.

Here we show the dataset can be explored through multidimensional visualisation techniques. In the data presented in this paper, the spatial dimension is described on 3 axes each for position and rotation, the mediolateral axis represented by the X-rotation axis and the anteroposterior axis represented by the Z-rotation axis. The X and Z position axes represent the individual’s horizontal position, and Y axis the user’s head height. We can make a base visualization of the positional movement in the scene (Fig. 8(a)) using the ex_visualization. ipynb script, which offers reproducibility but retains simplicity with limited interaction (such as hovering) and no representation of time. Six different steps of the scenario are shown with different colors, and the dots correspond to the position of the head. This visualization can be extended with the well-known visualization technique named space-time cube (STC)24,25 representation: a three-dimensional representation, taking the form of a cube. An example of this is shown in Fig. 8(b). This type of visualization is useful for the representation of the four fundamental sets of movement (space, time, thematic attributes and objects)26. It features two-dimensional space on its base, while the height dimension represents time. It depicts trajectories through line segments connecting spatial and temporal coordinates or data points while supporting the representation of thematic information, such as an individual’s demographics, emotional state, etc.

Code availability

The GUsT-3D framework with which the study was conceived and carried out is registered under an open CeCILL license and is openly available on Gitlab Inria (https://gitlab.inria.fr/anr-creattive3d-public/gust-3d).

References

Araújo, J. P. et al. Circle: Capture in rich contextual environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 21211–21221 (2023).

Ionescu, C., Papava, D., Olaru, V. & Sminchisescu, C. Human3.6m: Large scale datasets and predictive methods for 3d human sensing in natural environments. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 36, 1325–1339 (2014).

Zheng, Y. et al. Gimo: Gaze-informed human motion prediction in context. In 17th European Conference on Computer Vision (2022).

Zhang, S. et als. Egobody: Human body shape and motion of interacting people from head-mounted devices. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 180–200 (Springer, 2022).

Cao, Z. et al. Long-term human motion prediction with scene context. In European Conference on Computer Vision (2020).

Lohr, D., Aziz, S., Friedman, L. & Komogortsev, O. V. GazeBaseVR, a large-scale, longitudinal, binocular eye-tracking dataset collected in virtual reality. Scientific Data10 (2023).

Robert, F. A. S. et al. An integrated framework for understanding multimodal embodied experiences in interactive virtual reality. In 2023 ACM International Conference on Interactive Media Experiences (IMX) (2023).

Wu, H.-Y. et al. Designing guided user tasks in vr embodied experiences. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 6, 1–24 (2022).

Wodarski, P. et al. Assessment of gait stability and preferred walking speed in virtual reality. Acta of bioengineering and biomechanics 22, 127–134 (2020).

Calabrese, A. et al. Wet versus dry age-related macular degeneration in patients with central field loss: different effects on maximum reading speed. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52, 2417–2424 (2011).

De Beni, R., Pazzaglia, F. & Gardini, S. The role of mental rotation and age in spatial perspective-taking tasks: when age does not impair perspective-taking performance. Applied Cognitive Psychology: The Official Journal of the Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 20, 807–821 (2006).

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. & Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS quarterly 0, 157–178 (2012).

Hayotte, M., Thérouanne, P., Gray, L., Corrion, K. & d’Arripe Longueville, F. The french ehealth acceptability scale using the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology 2 model: instrument validation study. Journal of medical Internet research 22, e16520 (2020).

Hart, S. G. & Staveland, L. E. Development of NASA-TLX (task load index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. In Advances in psychology, vol. 52, 139–183 (Elsevier, 1988).

Kennedy, R. S., Lane, N. E., Berbaum, K. S. & Lilienthal, M. G. Simulator sickness questionnaire: An enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. The international journal of aviation psychology 3, 203–220 (1993).

Witmer, B. G. & Singer, M. J. Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence 7, 225–240 (1998).

Lang, P. Behavioral treatment and bio-behavioral assessment: Computer applications. Technology in mental health care delivery systems 0, 119–137 (1980).

Wu, H.-Y. et al. CREATTIVE3D multimodal dataset of user behavior in virtual reality, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8269108 (2024).

Taber, K. S. The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in science education 48, 1273–1296 (2018).

Gower, J. C. & Dijksterhuis, G. B.Procrustes Problems, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198510581.001.0001. (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Salvucci, D. D. & Goldberg, J. H. Identifying fixations and saccades in eye-tracking protocols. In Proceedings of the 2000 symposium on Eye tracking research & applications, 71–78 (2000).

Makowski, D. et al. NeuroKit2: A python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behavior Research Methods 53, 1689–1696, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01516-y (2021).

Gallo, F. F., Wu, H.-Y. & Sassatelli, L. DiVR: incorporating context from diverse VR scenes for human trajectory prediction. In CV4Metaverse workshop - 3rd Computer Vision for Metaverse Workshop / Co-located at ECCV 2024 - European Conference on Computer Vision (Milano, Italy, 2024). https://hal.science/hal-04771825.

Bach, B., Dragicevic, P., Archambault, D., Hurter, C. & Carpendale, S. A descriptive framework for temporal data visualizations based on generalized space-time cubes. In Computer graphics forum, vol. 36, 36–61 (Wiley Online Library, 2017).

Filho, J. A. W., Stuerzlinger, W. & Nedel, L. P. Evaluating an immersive space-time cube geovisualization for intuitive trajectory data exploration. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 26, 514–524, https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2019.2934415 (2020).

Andrienko, N., Andrienko, G. & Gatalsky, P. Exploratory spatio-temporal visualization: an analytical review. Journal of Visual Languages & Computing 14, 503–541 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the French National Research Agency through the ANR CREATTIVE3D project ANR-21-CE33-0001 and UCAJEDI Investissements d’Avenir ANR-15-IDEX-0001 (IDEX reference center for extended reality XR2C2). This work was granted access to the HPC resources of IDRIS under the allocation 2024-AD011014115R1 made by GENCI. It has also been partially supported by the Junior Chair of LS with Institut Universitaire de France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. coordinated the work (supervision, conceptualization, administration, funding, methodology, validation, software, data curation, and writing). S.R. and A.G. are primary contributors on the study methodology, validation, formal analysis, and administration (ethics review). F.R., M.W., and L.S. developed the software and conceived the study methodology. F.R. carried out the investigation (user study) with the assistance of K.P., J.D., C.Q., and F.G. F.G. and F.R. worked on the data curation (synchronization). K.P., S.R., and A.G. conducted validation on the gaze and physiology data. K.P. and S.R. provided the statistical modeling usage note. F.G. and L.S. validated the motion capture data and provided the machine learning usage note. MH provided the survey description, formal analysis, and validation. C.Q., A.M., and M.W. provided the data visualization usage note. P.K. contributed to the methodology (study design). All authors read and approved of the text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, HY., Robert, F., Gallo, F.F. et al. Exploring, walking, and interacting in virtual reality with simulated low vision: a living contextual dataset. Sci Data 12, 330 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04560-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04560-5