Abstract

The Anqing Six-end-white pig, a precious Chinese autochthonous breed, is mainly distributed in the Anhui Province, China. It is well documented for its excellent meat quality and crude-feed tolerance. However, the current lack of high-quality Anqing Six-end-white pig genome assembly poses a significant limitation for elucidating its germplasm characteristics and implementing genomic-level conservation. In this study, we assembled a high-quality chromosome-level genome; the genome size was 2.66 Gb with contig N50 = 90.48 Mb and scaffold N50 = 143.10 Mb. There were 23 gaps in the final assembled genome. A total of 1.16 Gb repeat sequences were identified and accounting for 43.52% of the genome. A total of 20,809 protein-coding genes were identified, and 99.18% of these genes were annotated. The predicted non-coding genes included 848 miRNAs, 4544 tRNA, 253 rRNA, and 2156 snRNAs in the genome. Genome completeness was 98.67% using BUSCO and 99.81% using Compleasm. This chromosome-level assembly provides a robust scientific foundation for the conservation, breeding, and exploration of genetic traits in the Anqing Six-end-white pig.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Pig (Sus scrofa), initially domesticated from wild boars independently in the Near East and China approximately 10,000 years ago1,2,3,4, have evolved into indispensable contributors to anthropogenic systems through their diverse roles. Nutritionally, they supply essential proteins, vitamins, and trace minerals critical for human dietary requirements5. Economically, industrialized swine husbandry drives agricultural economies, thus generating substantial revenue streams and employment opportunities5. Ecologically, swine has an exceptional capacity for sustainable nutrient cycling5. In translational medicine, the anatomical and physiological homology of pigs and humans has established them as pivotal preclinical models6. Culturally, pig hold profound symbolic significance in Eastern traditions, especially in Chinese cultural practices5. European and Asian pig exhibit different phenotypic and genomic characteristics7. The current pig genome, Sscrofa 11.1, was assembled using the Duroc Jersey pig, which was a most continuous assemblies and provide a pivotal role in mining the germplasm-related genes, thereby serving as an indispensable foundation for strategic genetic improvement initiatives in swine populations8. However, reliance on the pig genome Sscrofa 11.1 for evolutionary and population genetic analyses of Asian pig populations may result in the incomplete detection of Asian variations, hence, compromising the comprehensive characterization of their germplasm characteristics.

Anqing Six-end-white pig (Fig. 1), a representative native pig breed with a dual-purpose meat-lard type, is primarily distributed in surrounding mountainous areas including Taihu, Wangjiang, and Susong counties in China. In 2007, there were nearly 600 Anqing Six-white pigs. Recent data from 2019 show that the population has reached 4,617. Two national-level conservation farms were established to protect Anqing Six-white pigs. This breed is deeply loved by the local people, not only for providing meat protein and increasing farmers’ income but also for their position in local culture and history. In our prior investigations of Anqing Six-end-white pig, several candidate genes were identified that play important roles in regulating meat quality traits, lipid metabolism, and fat deposition9,10,11,12. However, the genetic basis of the characteristics in Anqing Six-end-white pig, has not yet been fully elucidated. The high-quality reference genome of Chinese indigenous pig breeds is a powerful tool to elucidate the characteristics of native breeds. Several high-quality pig genomes have been assembled, including Huai pig13, Chenghua pig14, Bamei pig15, and others16,17. However, a high-quality genome assembly of Anqing Six-end-white pig is still lacking, which greatly limits the elucidate of their germplasm characteristics and protection at the genomic level.

In this study, we assembled the first chromosome-level Anqing Six-end-white pig genome by combining short reads, PacBio HiFi (high fidelity) reads, and Hi-C (High-throughput chromosome conformation capture) sequencing data. The genome size and heterozygosity of Anqing Six-end-white pig were estimated to be 2.4 Gb and 0.61% according to 17-mer analysis of 129.62 Gb (57x) short reads. After de novo assembly with 229.34 Gb (95x) HiFi reads, the genome size was 2.69 Gb, composed of 62 contigs, and the contig N50 was 90.48 Mb with a 42.64% GC content. The final assembly genome (2.66 Gb) was anchored to 20 chromosomes (18 autosomes plus one X and Y), with scaffold N50 = 143.10 Mb through Hi-C assisted scaffolding. There were 23 gaps in the final assembled genome. The Anqing Six-end-white pig assembly captured 38 telomeres and 20 centromeres. Repeat sequences in the Anqing Six-end-white pig genome were annotated, and a 1.16 Gb repeat sequences (approximately 43.52% of the assembled genome) were identified. A total of 20,809 protein-coding genes were identified in our assembly, which harbored 36,142 transcripts with an average of 9.48 exons per gene. Non-coding RNAs in the assembly were annotated, and 848 miRNA, 4544 tRNA, 253 rRNA, and 2156 snRNA were identified. This study established a robust scientific foundation for the conservation, selective breeding, and exploration of superior genetic traits in the Anqing Six-end-white pig, offering critical genomic insights to safeguard germplasm resources and enhance agricultural sustainability.

Methods

Sample collection

A one-year-old male Anqing Six-end-white pig from the national Anqing Six-end-white pig conservation farm in Anqing city, Anhui province, China (30°19′N, 116°33′E) was used for genome sequencing (short reads, PacBio HiFi, and Hi-C) and assembly. Forty-two tissues of three one-year-old male Anqing Six-end-white pig were collected and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for RNA sequencing, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, stomach, longissimus dorsi muscle, adipose, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon and rectum. The pigs used in this study were healthy, and no genetic defects were observed in it or its parents. This study was conducted in accordance with and was approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Hefei, People’s Republic of China; Approval No. AAAS2023-4).

Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from the blood sample using a standard phenol–chloroform method and assessed using a 0.5% agarose gel and Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

For short read sequencing, the DNA were processed with fragmented, size selected, end-repaired, A-tailed, ligated to paired-end adaptors, PCR amplificated, and sequenced on the BGISEQ DNBseq-T7 sequencing platform at OneMore Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). In total, 141.65 Gb 150 bp paired-end reads were generated. Given that the original sequencing data may contain adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and undetected bases, Fastp18 (v0.23.2) software was used to filter the above information and 129.62 Gb data (Table 1) were retained to estimate the genome size of Anqing Six-end-white pig.

For SMRT sequencing library construction, genomic DNA was sheared, end-repaired, and ligated to SMRTbell adapters after exonuclease-mediated overhang removal. DNA damage was repaired prior to size selection (BluePippin system). Post-ligation exonuclease digestion eliminated the unligated fragments. Library quality was verified suing Qubit quantification and Fragment Analyzer sizing. Sequencing generated 12.39 million CCS reads (229.34 Gb, Table 1).

Hi-C libraries were constructed using 10 mL blood from a male Anqing Six-white pig. Chromatin was crosslinked (paraformaldehyde), digested (restriction enzyme), and ligated to preserve spatial interactions. After blunt-end repair with biotinylated dNTPs, crosslinks were reversed and the DNA was sheared (300–500 bp). Biotin-tagged fragments were enriched using streptavidin beads, followed by Illumina adapter ligation and PCR optimization. Library quality was verified by fluorometry (Qubit), fragment analysis (Bioanalyzer), and qPCR. Sequencing generated 257 Gb raw data, which were filtered to 249 Gb clean data (Table 1) with Fastp v0.23.2.

Total RNA was extracted from each tissue using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantity and purity were analysed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 and RNA 6000 Nano Labchip Kit (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Only RNA samples with suitable RNA electrophoresis results (28 S/18 S ≥ 1.0) and RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥ 7.5 could be analysed further. The RNA-seq libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000, which generated 150-bp paired-end reads. An average of 10.97 Gb for each tissue were obtained (Table 1). These RNA-seq data were used for whole genome protein-coding gene prediction.

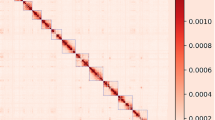

Genome size estimation and De novo genome assembly

Prior to genome assembly, key genomic features such as genome size and heterozygosity rate composition could be computationally estimated using the K-mer method. The 129.62 Gb clean data were subjected to a 17-mer frequency distribution analysis using GCE19 (v1.0.0) software (Fig. 2). The following equation was used to estimate the genome size of Anqing Six-end-white pig: G = K-mer number/K-mer Depth (where K-num is the total number of 17-mers, and K-depth denotes the K-mer depth, and G represents the genome size). To account for the confounding effects of genome heterozygosity on genome size estimation, K-mer exhibiting a depth of 1 were identified as sequencing errors. The derived error rate was used to refine the genome size calculation. The formula used was Revised Gsize = G x (1-Error Rate). The genome size and heterozygosity of Anqing Six-end-white pig were estimated to be 2.4 Gb and 0.61%.

De novo assembly of Anqing Six-end-white pig was performed using PacBio HiFi data and HiFiasm20 (v0.19.6) software. The HiFiasm assembly pipeline was constructed in three critical phases: (1) error correction and haplotype phasing of raw reads; (2) iterative construction of assembly graphs; and (3) refinement to generate chromosome-level contigs. To eliminate heterozygosity-induced redundancy, the purge_haplotigs21 (v1.0.4) software was applied to filter misassembled contigs by integrating the read coverage patterns and pairwise sequence alignment metrics. Contaminant sequences were systematically identified and removed by alignment against the NT database (v2023.07.04, https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/) using BLASTN22 (v2.11.0+). The genome size was 2.69 Gb, composed of 62 contigs, and the contig N50 was 90.48 Mb with a GC content of 42.64% (Table 2).

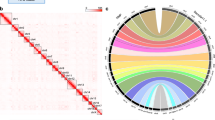

Hi-C assisted scaffolding

Following quality control of Hi-C data, the validated reads were processed through a hierarchical assembly pipeline: (1) data integrity was assessed using HiCUP23 (v0.7.2); (2) alignment to the draft genome was performed with Juicer24 (v1.5.6); and (3) chromosome-scale scaffolding was achieved through iterative integration of 3d-DNA (v180.922, https://github.com/theaidenlab/3d-dna) and HapHiC25 (v1.0.2), with manual curation guided by JuiceBox26 (v1.11.08) visualization of contact matrices. The final genome assembly was 2.66 Gb with contig N50 = 90.48 Mb and scaffold N50 = 143.10 Mb (Table 2). There were 23 gaps in the final assembled genome. The chromosomal anchoring efficiency was 98.80%. A heatmap was drawn for the interactions between the chromosomes (Fig. 3). The comparison between Anqing Six-end-white pig assembled genome and Sscrofa 11.1 was shown in Table 3.

Repetitive element identification

Repetitive sequence annotation was performed through an integrated pipeline combining three complementary strategies: (1) de novo prediction of tandem repeats using TRF27 (v4.09) software; (2) homology-based identification via RepeatMasker28 (v open-4.0.9) and RepeatProteinMask against the RepBase database (v20181026, http://www.girinst.org/repbase); and (3) a custom repeat library was constructed by integrating RepeatModeler29 (v open-1.0.11) and LTR_FINDER_parallel30 (v1.0.7), and was subsequently applied RepeatMasker (v open-4.0.9) to systematically annotate repetitive elements across the genome by de novo predictions. Consensus annotations were generated by merging non-redundant predictions from all approaches. A total of 1.16 Gb repeat sequences (approximately 43.52% of the assembled genome) were identified, of which 99.8% were classified as known repeat sequences (Table 4) Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of the genetic features of the Anqing Six-end-white pig genome in the 500 kb nonoverlapping windows. (a) GC content distribution. (b) Gene density distribution. (c) Total repeat density distribution. (d) LTR density distribution. (e) LINE density distribution. (f) DNA-TE density distribution.

Protein-coding genes prediction

Gene annotation was performed through an integrative multi-evidence framework: (1) ab initio predictions were generated using Augustus31 (v3.3.2) and Genscan32 under default parameters; (2) homology-based inference integrated cross-species protein alignments from Homo sapiens (GCF_000001405.40_GRCh38.p14), Mus musculus (GCF_000001635.27_GRCm39), Phacochoerus africanus (GCF_016906955.1_ROS_Pafr_v1), and Sus scrofa (GCF_000003025.6_Sscrofa11.1) through miniprot33 (v0.11-r234); and (3) transcriptomic evidence was incorporated through HISAT234 (v2.1.0)-guided RNA-seq alignments, followed by transcript assembly with StringTie35 (v1.3.5) and ORF prediction via TransDecoder (v5.5.0, https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder). BUSCO36 (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs, v5.7.1) was used for predictions based on Augustus (v3.3.2) and lineage-specific ortholog libraries (laurasiatheria_odb10). MAKER237 (v2.31.10) was used to integrate preliminary gene models into a consensus set. Final refinement was performed using HiFAP (developed in-house). In total, 20,809 protein-coding genes were identified, which harbored 36,142 transcripts with an average of 9.48 exons per gene (Table 5).

Gene function annotation

Protein-coding genes were functionally analyzed using ten datasets: NR_Annotation, SwissProt_Annotation, TrEMBL_Annotation, KOG_Annotation, TF_Annotation, InterPro_Annotation, GO_Annotation, KEGG_ALL_Annotation, KEGG_KO_Annotation, and Pfam_Annotation. Functional annotation was performed through dual complementary strategies: (1) sequence similarity analysis using diamond38 blastp against TrEMBL39, SwissProt39, NR40, KOG (https://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/COG/KOG/), COG41, GO42, and KEGG43 databases, with KOBAS44 (v3.0) mapping KEGG orthologs to metabolic pathways; and (2) domain/motif profiling through InterProScan45 (v5.61–93.0) integrating InterPro46 databases to obtain protein conserved sequences, motifs, domains and other information. Hmmscan from the HMMER3 (v3.3.1) software was used to annotate conserved sequence information, such as transcription factors, Pfam, and motif based on multiple sequence alignment and the hidden Markov model47. A total of 20,638 genes (99.18% of predicted genes) were annotated (Table 6).

Annotation of non-coding RNAs (ncRNA)

RNA annotation employed species-specific approaches based on molecular features: (1) tRNA were identified using tRNAscan-SE48; (2) rRNA were detected via BLASTN against conserved ribosomal sequences from phylogenetically proximal species (Sus scrofa and Phacochoerus africanus); and (3) miRNAs and snRNAs were annotated with INFERNAL49 (v1.1.4) by scanning against the Rfam50 (v14.8) database. The predicted non-coding genes included 848 miRNAs, 4544 tRNA, 253 rRNA, and 2156 snRNAs in the Anqing Six-end-white pig genome (Table 7).

Detecting telomeric and centromeric regions

Telomeric regions were systematically identified across the Anqing Six-end-white pig genome using quarTeT51 software (version 1.1.4), which detects the consensus telomeric repeat motif AACCCT. Among all chromosomes, 18 exhibited telomeric repeats at both termini, whereas two chromosomes showed terminal repeats at a single end (Table 8). According to the results of repeat annotation in the genome annotation, regions with high repeat distribution were selected as candidate centromere inputs, and srf52 software ((https://github.com/lh3/srf)) was used for centromere prediction. The srf software identifies multiple centromere candidate regions and multiple repeat types, and then selects the candidate regions to obtain the predicted centromere region (Table 8). Visualization of porcine telomeres and centromeres is shown in Fig. 5.

Overview of the telomeres and centromeres. The upper part of the chromosome represents the overall length of the chromosome and the location of the assembled telomeres and centromeres. The lower part of the chromosome represents the distribution of the assembled conting on the corresponding position of the chromosome.

Data Records

The assembled genome has been deposited at NCBI GenBank under the accession number GCA_050231125.153. The PacBio HiFi, Hi-C, short reads, and RNA-seq data were submitted to the Genome Sequence Archive of the China National Center for Bioinformation (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/) under the project PRJCA03772254,55. The accession number of CRR1702913 and CRR1702914 for Hi-C. The accession number of CRR1702915 for short reads. The accession number of CRR1702916 and CRR1702917 for PacBio HiFi. The accession number of from CRR1702918 to CRR1702959 for RNA-seq. Additionally, files containing the protein-coding gene annotation, non-coding RNA prediction, and repeat annotation of Anqing Six-end-white pig have been deposited in the Figshare database56 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28943891).

Technical Validation

Multiple evaluation metrics were utilized to assess the quality and robustness of the Anqing Six-end-white pig assembly genome. Firstly, the short reads, PacBio HiFi reads, and RNA-seq data were mapped to the genome with bwa57 (v0.7.12-r1039), minimap258 (v2.24-r1122), and Hisat2, respectively. Alignment rates were 99.14% for short-read data, 99.99% for PacBio HiFi reads, and 89.43% for RNA-seq data. Secondly, following short-read alignment, variants (SNPs and InDels) were identified using SAMtools59 (v1.9), Picard (v1.124), and GATK60 (v4.4.0.0). The homozygous SNP rate (0.001%), homozygous InDel rate (0.001%), heterozygous SNP rate (0.346%), and heterozygous InDel rate (0.069%). The exceptionally low homozygous rates indicate high assembly accuracy. Thirdly, The Merqury61 software (v1.3) was employed to assess the quality values (QV) of Anqing Six-end-white pig genome using a combination of short-read and PacBio HiFi reads. The results revealed that the QV based on short-read and PacBio HiFi reads were 49.3113 and 72.6645 respectively. Fourthly, BUSCO36 (v5.7.1) and Compleasm62 (v0.2.6) analyses were conducted to evaluate the completeness of our assembly by laurasiatheria_odb10. BUSCO analyses revealed that 12,071(98.67%) of the 12,234 conserved single-copy genes in our assembly, of which 12034 were single, 37 were duplicated, and 78 were fragmented matches (Table 9). Compleasm analyses revealed that 12,211(99.81%) of the 12,234 conserved single-copy genes in our assembly, of which 12193 were single, 18 were duplicated, and 9 were fragmented matches (Table 10). Overall, these findings indicate the high quality of the genome assembly.

Code availability

The software versions, settings and parameters used are described below. No custom code was used during this study for the curation and/or validation.

Fastp v0.23.2: -l 50

GCE v1.0.0: -k 17

HiFiasm v0.19.6: default

purge_haplotigs v1.0.4: default

BLASTN v2.11.0+: -evalue 0.00001 -max_hsps 1

HiCUP v0.7.2: default

Juicer v1.5.6: default

3d-DNA v180.922: -r 0

HapHiC v1.0.2: --NM 3

JuiceBox v1.11.08: default

TRF v4.09: 2 7 7 80 10 50 2000 -d -h

RepeatMasker v open-4.0.9: -nolow -no_is -norna

RepeatModeler v open-1.0.11: default

LTR_FINDER_parallel v1.0.7: default

Miniprot v0.11-r234: --gff-only -O 11 -E 1 -F 23 -C 1 -B 5 -G 200000 -j 1

HISAT2 v2.1.0: --dta

StringTie v1.3.5: default

TransDecoder v5.5.0: default

BUSCO v5.7.1: --miniprot -m genome -f --offline

MAKER2 v2.31.10: max_dna_len = 3000000 min_contig = 10000 pred_flank = 500 min_protein = 30

HMMER3 v3.3.1: hmmsearch -E 1e-05 --domE 1e-05

Diamond v2.0.14: --evalue 1e-05

tRNAscan-Se v1.3.1: -q

Rfam v14.8: cmscan --rfam –nohmmonly

quarTeT v1.1.4: -c animal

bwa v0.7.12-r1039: default

minimap2 v2.24-r1122: default

SAMtools v1.9: default

Picard v1.124: default

GATK v4.4.0.0: default

References

Ai, H. et al. Adaptation and possible ancient interspecies introgression in pigs identified by whole-genome sequencing. Nature genetics 47, 217–225, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3199 (2015).

Frantz, L. A. F. et al. Evidence of long-term gene flow and selection during domestication from analyses of Eurasian wild and domestic pig genomes. Nature genetics 47, 1141–1148, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3394 (2015).

Groenen, M. A. M. et al. Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature 491, 393–398, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11622 (2012).

Larson, G. et al. Worldwide phylogeography of wild boar reveals multiple centers of pig domestication. Science 307, 1618–1621, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1106927 (2005).

China National Commission of Animal Genetic Resource. Animal Genetic Resource in China. Pigs; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, (2011).

Swindle, M. M., Makin, A., Herron, A. J., Clubb, F. J. Jr & Frazier, K. S. Swine as models in biomedical research and toxicology testing. Veterinary pathology 49(2), 344–356, https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985811402846 (2012).

Li, M. et al. Comprehensive variation discovery and recovery of missing sequence in the pig genome using multiple de novo assemblies. Genome research 27, 865–874, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.207456.116 (2017).

Warr, A. et al. An improved pig reference genome sequence to enable pig genetics and genomics research. Gigascience 9, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa051 (2020).

Wang, Y. L. et al. RNA sequencing analysis of the longissimus dorsi to identify candidate genes underlying the intramuscular fat content in Anqing Six-end-white pigs. Animal genetics 54(3), 315–327, https://doi.org/10.1111/age.13308 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Identification of Signatures of Selection by Whole-Genome Resequencing of a Chinese Native Pig. Frontiers in genetics 11, 566255, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.566255 (2020).

Zhang, X. D. et al. Association between ADSL, GARS-AIRS-GART, DGAT1, and DECR1 expression levels and pork meat quality traits. Genetics and molecular research 14(4), 14823–30, https://doi.org/10.4238/2015.November.18.47 (2015).

Hu, H. et al. Comparative analysis of meat sensory quality, antioxidant status, growth hormone and orexin between Anqingliubai and Yorkshire pigs. J. Appl. Anim. Res 47, 357–361, https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2019.1643729 (2019).

Du, H. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Huai pig (Sus scrofa). Scientific data 11(1), 1072, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03921-w (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. A chromosome-level genome of Chenghua pig provides new insights into the domestication and local adaptation of pigs. International journal of biological macromolecules 270, 131796, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131796 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Pangenome and genome variation analyses of pigs unveil genomic facets for their adaptation and agronomic characteristics. iMeta 3(6), e257, https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.257 (2024).

Ma, H. et al. Long-read assembly of the Chinese indigenous Ningxiang pig genome and identification of genetic variations in fat metabolism among different breeds. Molecular ecology resources 22(4), 1508–1520, https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13550 (2022).

Zhou, R. et al. The Meishan pig genome reveals structural variation-mediated gene expression and phenotypic divergence underlying Asian pig domestication. Molecular ecology resources 21(6), 2077–2092, https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13396 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34(17), i884–i890, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Liu, B. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. Quantitative Biology 35, 62–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-4005(96)02015-1 (2013).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature methods 18(2), 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Roach, M. J., Schmidt, S. A. & Borneman, A. R. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC bioinformatics 19(1), 460, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-018-2485-7 (2018).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology 215(3), 403–410, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990).

Wingett, S. et al. HiCUP: pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Research 4, 1310, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7334.1 (2015).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell systems 3(1), 95–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 (2016).

Zeng, X. et al. Chromosome-level scaffolding of haplotype-resolved assemblies using Hi-C data without reference genomes. Nature plants 10(8), 1184–1200, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01755-3 (2024).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox Provides a Visualization System for Hi-C Contact Maps with Unlimited Zoom. Cell systems 3(1), 99–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012 (2016).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic acids research 27(2), 573–580, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.2.573 (1999).

Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker Open-3.0. [http://repeatmasker.org] (1996)

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018 (2005).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_FINDER_parallel: parallelization of LTR_FINDER enabling rapid identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Mobile DNA 10, 48, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-019-0193-0 (2019).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic acids research 34, W435–W439, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl200 (2006).

Burge, C. & Karlin, S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. Journal of molecular biology 268(1), 78–94, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951 (1997).

Slater, G. S. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC bioinformatics 6, 31, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-6-31 (2005).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature biotechnology 37(8), 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature biotechnology 33(3), 290–295, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Molecular biology and evolution 38(10), 4647–4654, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab199 (2021).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC bioinformatics 12, 491, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-491 (2011).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H. G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nature methods 18(4), 366–368, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x (2021).

Coudert, E. et al. Annotation of biologically relevant ligands in UniProtKB using ChEBI. Bioinformatics 39(1), btac793, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac793 (2023).

Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic acids research 49(D1), D10–D17, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa892 (2021).

Galperin, M. Y. et al. COG database update: focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic acids research 49(D1), D274–D281, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1018 (2021).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nature genetics 25(1), 25–29, https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Ogata, H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic acids research 27(1), 29–34, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.1.29 (1999).

Bu, D. et al. KOBAS-i: intelligent prioritization and exploratory visualization of biological functions for gene enrichment analysis. Nucleic acids research 49(W1), W317–W325, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab447 (2021).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30(9), 1236–1240, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 (2014).

Paysan-Lafosse, T. et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic acids research 51(D1), D418–D427, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac993 (2023).

Eddy, S. R. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 14(9), 755–763, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755 (1998).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic acids research 49(16), 9077–9096, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab688 (2021).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

Griffiths-Jones, S., Moxon, S., Marshall, M., Khanna, A. & Eddy, S. R. & Bateman, A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic acids research 33, D121–D124, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki081 (2005).

Lin, Y. et al. quarTeT: a telomere-to-telomere toolkit for gap-free genome assembly and centromeric repeat identification. Horticulture research 10(8), uhad127, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhad127 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Chu, J., Cheng, H. & Li, H. De novo reconstruction of satellite repeat units from sequence data. Genome research 33(11), 1994–2001, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.278005.123 (2023).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_050231125.1 (2025).

NGDC Genome Sequence Archive. https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA024101 (2025).

NGDC Genome Warehouse. https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/93577/show (2025).

Zhang, W. et al. A high-quality Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Anqing Six-end-white pig (Sus scrofa). Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28943891 (2025).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25(14), 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34(18), 3094–3100, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 (2018).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25(16), 2078–9, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research 20(9), 1297–1303, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.107524.110 (2010).

Rhie, A. et al. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biology 21, 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 (2020).

Huang, N. & Li, H. Compleasm: a faster and more accurate reimplementation of BUSCO. Bioinformatics 39(10), btad595, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad595 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the grants from Anhui Provincial Financial Agricultural Germplasm Resources Protection and Utilization Fund Project, The Special Fund for Anhui Agricultural Research System (AHCYJSTX-05-12, AHCYJSTX-05-23), Anhui Provincial Science and Technology Mission Project, Anhui Province Academic and Technical Leader Candidate Project (No.2022H300), 2025 Institutional Research Program of Anhui Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2025YL043). We thank Wuhan Onemore-tech Co. Ltd. for their kindly helps in data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-L.W. and W.Z. conceived and designed the experiments; W.Z. designed the analytical strategy and performed analysis processes. M.Z., S.-G.S. and L.-Q.L. performed the sampling; M.L. extracted the genomic DNA and RNA; The initial draft of the manuscript was authored by W.Z., who incorporated detailed feedback from all the authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interests that represent conflicts of interest in connection with the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Zhou, M., Liu, L. et al. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Anqing Six-end-white pig (Sus scrofa). Sci Data 12, 1656 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05945-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05945-2