Abstract

The fundamental purpose of this research is to elaborate on slip boundary conditions and the flow of three-dimensional, stable, incompressible, rotating movements of nanoparticles lying across a stretchable sheet. The mathematical model for fluid flow is created using the assumptions stated above. The partial differentials are produced after utilizing boundary layer estimates. The partial differential governing equations are reduced into three coupled ordinary differential equations by using similarity transformations. After, applying transformations the system is solved numerically. Numerical results are approved with the help of the MATLAB bvp4c algorithm. The analysis shows that velocity and temperature are strongly dependent on essential parameters like stretching ratio, velocity slip, rotation, thermal slip parameter, and Prandtl number. Numerical values of distinct parameters on heat flux and skin friction factors are shown in a tabulated form. Partial velocity and thermal slip are applied to the temperature surface. The comparison among the nano-sized particles copper oxide and silver with water base nanofluid affecting velocity and temperature fields are used for analysis. Moreover, the Graphical depiction designates that the velocity and temperature spreading of the thermal slip parameter is increasing. It is observed that Ag-water is the best heat carrier as compared to CuO-water nanofluid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The exploration of heat transfers plus boundary level movement through an extending surface is necessary for industrial as well as engineering technology. Types of alike flows include metallurgy, precipitation liquid films, wire drawing, hot rolling, produced filaments, etc. In all these cases, the final item feature is based happening the factor of friction and heat instability1,2. In these flows, the surface is often expected to be extended linearly. Nonetheless, in the real world, the stretching surface does not need to be linear as contended by Gupta et al.3. In most industrial and mechanical applications, heat transfer, which is assumed to be the most important process, has a constraint due to the essentially weak ordinary liquids of thermal conductivity. Therefore, significant attempts have been taken to resolve this constraint after Maxwell worked more than a hundred years ago on combining particles with a millimeter or micrometer scale in fluid4,5,6,7. As technology progress and power demand increase then the world needs to identify modern apparatus and devices that improve thermal dissipation. Heat flux has various industrial utilization of heat transfer that deal with temperatures that rise and fall equally. Due to their lower thermal conductivity, most fluids are not good heat conductors. To address this problem and improve these liquids' conductivity or other heat characteristics, a newly developed technique is used that involves the introduction of nanoparticles that are excellent heat conductors, such as titanium, iron, and aluminum through fluids8.

Choi was the one who initially coined the term "nanofluids"9. A nanofluid is a solution that includes a combination of nanoparticles. Nanoparticle characteristics exhibit a great deal of refinement at low nanoparticle concentrations. Nanoparticles are naturally formed in carbides, oxides, and carbon oxide tubes, which are employed in nanofluids. Base fluids are often ethylene glycol, water, plus thin oil. Understanding the behavior of nanofluids Hoghoughi et al.10 examined several models using a combination of nano-sized particles in a liquid. Wong and Long11 have explored the numerous tenders of nanofluids. grinding, domestic refrigerators, pharmaceutical processes, space technology, drug delivery, and nuclear reactor coolant by targeting especially copper nanoparticles that improve abnormal heart expansion and rotten arteries that have been established as a non-invasive technique to encounter heart diseases12. Numerous researchers have theoretically and experimentally explored the thermo-physical assets of nanofluid in the previous two decades. Several articles have demonstrated that the temperature rate transmission is higher than with typical base liquids13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

The main assumption of the Navier–Stokes concept is the no-slip border rule. Besides, this rule does not apply in some cases, such as in liquids, polymer solutions, emulsions, and foams. Whenever a fluid particle may occur near the extending border, partial slip velocity is applied. The situation of velocity slip occurs when the liquid to solid boundary flow is not applied evenly, which was examined in the light of specific conditions by wang31. After that, many researchers32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 examined the problems, which were identified for velocity slip conditions at the boundary. The impression of velocity slip and temperature energy happening in the magneto- hydrodynamic mixture \({Cu-Al}_{2}{O}_{3}/\) water movement of nanofluid through a porous stretched area was investigated by Wahid et al.41. The phenomena of suspended atoms interacting with fluid across a flexible spinning disc are investigated by Turkyilmazoglu42. Also, Turkyilmazoglu explored the wall extending revolving fluxes in inertial and spinning contexts are considered in magnetohydrodynamics43.

The liquids that show boundary slip have an inclusive variety of uses, including a rubbing of implanted heart valves plus interior chambers. Mukhopadhyay studied thermal dissipation stratified MHD flows caused by an exponentially stretches sheet44. Thermophoretic particle deposition was used to explore a three-dimensional mixture of nano-fluid flow over a revolving expansion/contraction disc observed by Gowda et al.45. Jayadevamurthy et al.46 introduced attention to irregular mechanics of bioconvective mixed nanofluid flow across a rotating disc that moves uphill and downhill. Kotresh et al.47 explored the taxation of Arrhenius motivation energy in the overextended flow of nanofluid above a spinning disc. The influence of a realistic magnetic field happening the flow of liquid suspension among two revolving stretchy discs was studied by Radhika et al.48. The Cattaneo–Christov heat flux model was used by Gireesha et al.49 to study the MHD flow and molten heat transfer of grubby Casson fluid across a stretched sheet. Agrawal et al.50 studied the magneto Marangoni flow of γ − AL2O3 nanofluids above a stretching surface embedded in the porous medium through thermal radiation and heat source/sink effects. Khan et al. 51 introduced the stability analysis of dual solutions of nanomaterial flow comprising titanium alloy (Ti6, Al4 V) suspended in Williamson fluid through a thin moving needle with nonlinear thermal radiation. Iqbal et al.52 scrutinized the effect of induced magnetic field on thermal enhancement in gravity-driven Fe3O4 ferrofluid flow through the vertical non-isothermal surface. Chabani et al.53 demonstrated hybrid MHD nanofluid flow in a triangular enclosure. Over a stretched sheet, a rotating flow of MHD hybrid nanoparticles with heat radiation is investigated numerically by Shoaib et al.54. For innovative COVID-19 dynamics, a stochastic numerical study based on hybrid NAR-RBFs networks nonlinear SITR model was performed by Shoaib et al.55. Many researchers work on nanofluids in their studies56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63.

As a result, our goal is to make single-particle nanofluids with better characteristics. A revolving solution (Ag or CuO / water) causing slippage and thermal effects are analyzed in the present paper. The inspiration of velocity and thermal slip on rotating nanofluid and both types of nano-particles in three-dimensional flow is a unique component of this comparative research. Silver and copper oxide are exploited as nanoparticles, using water as the base fluid. The slippage velocity and thermal effects of this mixture of Ag-water and CuO-water nanoparticles have never been discussed in the literature. For the physical modeling of structure, the dual-phase model of nanofluid is used. The partial variance equations are concentrated to one that is easier to understand. The numerical results are achieved using Matlab and the bvp4c approach, a limited difference algorithm that executes the three-stage Lobatto method. The quality of velocity and temperature profiles is visually represented by various values of significant parameters.

Problem formulation

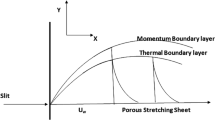

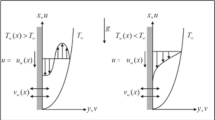

Let us Consider a steady, incompressible, three-dimensional, laminar rotating flow on a surface that is exponentially extending. Figure 1 describe the geometry of the problem. The flow is rotated around the z-axis at a constant angular velocity in the area \(z\ge 0\). Exponentially surface is stretched with velocity \({u}_{w}\) and \({v}_{w}\). Copper oxide and silver are nano-sized elements with base liquid water (H2O) are considered for analysis. The governing three-dimensional equations64 become simpler when the boundary layer approximation is used and the pressure gradient and viscous dissipation are taken into account.

Continuity equation

Momentum equations

Energy equation

where \({\nu }_{nf}\) is a kinematic viscosity, \({\alpha }_{nf}\) is the diffusivity of heat, and T stands for the temperature of the nanofluid.

The limitations are as follows:

The dimensionless quantities are

Suitable similarity transformations are given below

The continuity equation is identically fulfilled after implementing the similarity transformations to Eqs. (1–5) whereas the momentum and energy equations become

here

The transformed boundary conditions are

where, \(\alpha\) stands for velocity slip, \(\lambda\) denotes by stretching ratio, \(\beta\) represents the thermal slip parameter.

The Nusselt number and skin friction factors are also described.

The wall shear stresses \(({\tau }_{wx}, {\tau }_{wy})\) and heat flux \({(q}_{w})\) are expressed as

Now using Eqs. (7–8) and (16) in (15), we get

where Re is the Reynolds number in the area.

Numerical scheme

A numerical result of the problem is obtained by using the MATLAB bvp4c algorithm. The governing PDEs with high non-linearity are converted into ODEs as a result of appropriate transformations. Equations (9), (10), and (11) are combined to form a first-order linear equation system. To fulfill the asymptotic boundary criteria, appropriate initial guesses are established (13). The following are the new variables

Therefore, the corresponding Eqs. (9–11) becomes

with boundary conditions

The results show how dimensionless variables like stretching ratio, rotation parameter, slippage, temperature slip parameter, and Prandtl number influence the number of skin factors and the ratio of heat flux for the nanoparticles of CuO as well as Ag-water. The following graphs and tables depict the answers to the current problem.

Graphical outcomes and discussions

This section looks at the effects of velocity in both directions \(\left( {f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right), g^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right)\) and thermal performance \(\theta \left( \eta \right)\) for a few relevant parameters alike as velocity slip α, Prandtl number \(Pr,\) thermal slip β for the CuO as well as Ag-water nanofluid. We obtain graphical findings in the existence of nanoparticles on velocity and temperature profiles that give the real influence of these parameters. Figure 2a,b are organized to reveal the influence of α on the velocity filed \(\left( {f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right)\) for CuO and Ag-water solution. Figure 2a demonstrates the impression of the slip α parameter on the \(f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)\). While increasing the α, outcomes in a significant decline in the horizontal velocity distribution for CuO-water nanofluid. Also, Fig. 2b demonstrates that by growing of α parameter so the velocity curve is decreasing for Ag-water nanofluid. Figure 3a,b elaborate on the inspiration of the velocity slip α parameter along the vertical velocity field \(\left( {g^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right)\) for both types of nanofluids. Figure 3a represents that increases the values of α so the velocity profile shows downward for CuO-water nanofluid. From Fig. 3b, when an increasing velocity slip parameter α, the vertical velocity curve for Ag-water nanofluid is declined. This is because the speed of the molten nearby the surface in the existence of the slip does not remain as similar to the stretching surface velocity. Therefore, by increasing the α the slip velocity intensifies. It consequently reduces the velocity of the liquid since, below the slip form, the straining of the extending sheet can mostly be passed through the liquid. It is observed that the slip α parameter markedly influences the solutions. Similarly, the thickness of the boundary level declines as α is growing upward. In Figs. 4a,b and 5a,b expression that the influence of the thermal slip β parameter over the velocity distribution \(\left( {f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right), g^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right)\) are depicted for both types of nanoparticles with water-based. Figure 4a,b show that within growing the values of thermal parameter β, the velocity filed \(\left( {f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right)\) is increased for both types of nanoparticles. In Fig. 5a,b denote that growing the values of β, then the velocity curve growing upward for Ag-water nanofluid. From Figs. 6a,b and 7a,b establish the impact of (Pr) and thermal slip parameter β over temperature element \(\theta \left( \eta \right)\) for CuO-water and Ag-water. It can be shown that, from Fig. 6a,b, when increases Pr, then the temperature distribution is decline for both types of nanofluids. Figure 7a,b deliberate on the impression of thermal slip parameter β above the temperature \(\theta \left( \eta \right)\) profile. This implies that through growing the rate of β on the temperature curve \(\theta \left( \eta \right)\) increases for the CuO-water and Ag-water of nanofluids. Physically, additional heat is transferred from the surface toward the liquid with rising slip parameter β, which results in an increasing temperature profile. The distribution of temperature converges at 0.1 in the existence of the Ag-water and the temperature curve for CuO-water converges at 0.3. So, we observe that Ag-water is the best nanofluid as compared to CuO-water nanofluid. Physically, the CuO-water or Ag-water nanofluid has a comparatively upper thermal conductivity in production with the base fluid and nanoparticle. Figures 8a,b and 9a,b show the behavior of skin friction coefficient beside the x-axis \(C_{fx} { }\) i.e. \(\frac{1}{{\left( {1 - \phi } \right)^{2.5} }}f^{\prime\prime}\left( 0 \right),{ }\) and y-axis \(C_{fy}\) i.e. \(\frac{1}{{\left( {1 - \phi } \right)^{2.5} }}g^{\prime\prime}\left( 0 \right),\) with volume fraction φ for various morals of velocity slip α parameter by the boundary. It is analyzed from Fig. 8a,b display that the skin friction about x-direction is reduced with the rise in the velocity slip α and volume fraction φ. Also, denoted from Fig. 9a,b that within increased α parameter, the magnitude of friction amount \(C_{fy}\) is declines for CuO-water as well as Ag-water. Figure 10a,b elaborates on the variation of velocity slip α with the volume fraction φ on the local heat flux. Here, it is recognized that the local thermal dissipation increases when an increase the value of volume fraction φ, velocity slip α parameter for CuO as well as Ag-water respectively. From these Figs. 8a,b, 9a,b and 10a,b, we observe that when velocity slip parameter α increases about x–y-direction, the length of skin friction decreases. But if we check the opposite, it has an opposing impact on the rate of thermal dissipation i.e. it allows the rate of heat dissipation to increase. Table 1, explicates the thermo-physical features of nanomaterials (CuO-water and Ag-water). Table 2, shows that the basic physical features of nanoparticles (CuO and Ag) and base liquid (H2O) are examined in the paper. Table 3, numerical values for coefficients of skin friction (\(C_{fx}\),\({ }C_{fy}\)) and local thermal dissipation (Nux )for variations of velocity slip (α) parameter, rotation (γ) parameter, thermal slip (β) parameter, stretching ratio (λ) parameter, temperature exponent (A), volume fraction φ plus Prandtl number (Pr = 6.2) for CuO-water nanofluid. Table 3, the variation of distinct parameters α, γ, β, A, λ, and Pr = 6.2 on the quantity of skin friction \(\left( {C_{fx} , C_{fy} } \right)\) and Nusselt number (Nux ) for the Ag-water of nanofluid. From Table 3, we notice that with growing the α, γ, and λ the magnitude of skin friction coefficient and heat flux increases at the surface. Also, in Table 4, when increasing the values of φ along with the variation of α, γ, β, A, and λ the magnitude of the coefficient of skin friction \(\left( {C_{fx} , C_{fy} } \right)\) decreases but values of Nusselt number (Nux) increase. However, when \(\varphi\) increases, the value of heat dissipation increases since the thermal conductivity of nanomaterials is greater than the base liquid and these nanoparticles contain less specific heat than the base fluid. Table 5 describes the results of relevant factors on the magnitude of the velocity about the x-axis at the surface. The comparison in Table 5 demonstrates a high degree of concordance with previously reported data.

Final remarks

This article analyzes the steady, three-dimensional boundary layer rotating nanofluid flow with partial and thermal slippage past an exponentially extending surface. Physical characteristics' effects on two side velocities, temperature field, and friction variables \(\left({C}_{fx}, {C}_{fy}\right)\) and \(({{\varvec{N}}{\varvec{u}}}_{{\varvec{x}}})\) are addressed comprehensively. The following are the major conclusions:

-

Lateral directions \(\left( {f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right), g^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right)\) velocities are declines for growing the values of velocity slip α parameter.

-

By raising the β parameter then the velocity profile along with two directions \(\left( {f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right), g^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)} \right)\) velocities increases respectively.

-

Silver (Ag) nanoparticle is better heat carriers as compared to Copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticle.

-

The temperature curve and thermal boundary layer width rise while growing the thermal slip β parameter for both types of nanofluids.

-

Temperature distribution θ(η) is decreasing while increasing Pr.

-

By increasing the value of α, skin friction factors \(({C}_{fx}, {C}_{fy})\) diminishes but heat flux rises at the surface.

Data availability

The datasets used or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- K :

-

Velocity slip factor

- \(\gamma\) :

-

Rotation parameter

- u 0, v 0 :

-

Rates of stretching

- C fx, C fy :

-

Skin friction along the x-direction and y-direction

- l :

-

Thermal slip factor

- Pr :

-

Prandtl number

- Nu x :

-

Nusselt number

- u,v,w :

-

Components of velocity in x, y, and z-direction

- \({T, T}_{w},{T}_{\infty }\) :

-

The temperature of the fluid, ambient temperature, wall temperature

- \(\varphi\) :

-

Nano-particles volume fraction

- \(\theta\) :

-

Dimensionless temperature

- \(\Omega\) :

-

Constant angular velocity

- \(\eta\) :

-

Dimensionless space variable

- \(\upsilon_{f} \;,\,\;\upsilon_{nf}\) :

-

Kinematic viscosities of the base fluid and nanofluid respectively

- \(\mu_{f} \;,\,\;\mu_{nf}\) :

-

Dynamic viscosities of the base fluid and nanofluid respectively

- \(\rho_{s} \;,\,\;\rho_{f} \;,\,\;\rho_{nf\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;}\) :

-

The density of solid nanoparticles, base fluid, and nanofluid respectively

- \(\alpha_{nf}\) :

-

Thermal diffusivity of nanofluid

- \(k_{s} \;,\,\;k_{f} \;,\,\;k_{nf}\) :

-

Thermal conductivities of solid nanoparticles, base fluid, and nano-fluid respectively

- \((Cp)_{nf} \;,\,\;(Cp)_{f}\) :

-

Volumetric heat capacity of nanofluid and base fluid respectively

References

Hayat, T., Nadeem, S. & Khan, A. U. Aspects of 3D rotating hybrid CNT flow for a convective exponentially stretched surface. Appl. Nanosci. 10(8), 2897–2906 (2020).

Hayat, T., Nadeem, S. & Khan, A. U. Rotating flow of Ag-CuO/H2O hybrid nanofluid with radiation and partial slip boundary effects. Eur. Phys. J. E 41(6), 1–9 (2018).

Gupta, M. A. & Gupta, A. K. Psoriasis and sex: A study of moderately to severely affected patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 36(4), 259–262 (1997).

Maxwell, J. A. Some marshallian concepts, especially the representative firm. Econ. J. 68(272), 691–698 (1958).

Happel, J. Viscous flow in multiparticle systems: Slow motion of fluids relative to beds of spherical particles. AIChE J. 4(2), 197–201 (1958).

Hamilton, R. L. & Crosser, O. K. Thermal conductivity of heterogeneous two-component systems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1(3), 187–191 (1962).

Ahuja, A. S. Augmentation of heat transport in laminar flow of polystyrene suspensions. I. Experiments and results. J. Appl. Phys. 46(8), 3408–3416 (1975).

Choi, S. U. Nanofluids: From vision to reality through research. J. Heat Transfer 131(3), 033106 (2009).

Choi, S. U., & Eastman, J. A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles (No. ANL/MSD/CP-84938; CONF-951135–29). Argonne National Lab., IL (United States) (1995).

Hoghoughi, G., Izadi, M., Oztop, H. F. & Abu-Hamdeh, N. Effect of geometrical parameters on natural convection in a porous undulant-wall enclosure saturated by a nanofluid using Buongiorno’s model. J. Mol. Liq. 255, 148–159 (2018).

Wong, K. V., & De Leon, O. Applications of nanofluids: current and future. In Nanotechnology and Energy (pp. 105–132). Jenny Stanford Publishing (2017).

Sadaf, H. & Nadeem, S. Influences of slip and Cu-blood nanofluid in a physiological study of cilia. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 131, 169–180 (2016).

Rahman, S. U., Ellahi, R., Nadeem, S. & Zia, Q. Z. Simultaneous effects of nanoparticles and slip on Jeffrey fluid through tapered artery with mild stenosis. J. Mol. Liq. 218, 484–493 (2016).

Akbarzadeh, M., Rashidi, S., Bovand, M. & Ellahi, R. A sensitivity analysis on thermal and pumping power for the flow of nanofluid inside a wavy channel. J. Mol. Liquids 220, 1–13 (2016).

Shirvan, K. M., Mamourian, M., Mirzakhanlari, S. & Ellahi, R. Numerical investigation of heat exchanger effectiveness in a double pipe heat exchanger filled with nanofluid: a sensitivity analysis by response surface methodology. Powder Technol. 313, 99–111 (2017).

Shehzad, N. Z. A. E. R. V. K., Zeeshan, A., Ellahi, R. & Vafai, K. Convective heat transfers of nanofluid in a wavy channel: Buongiorno’s mathematical model. J. Mol. Liq. 222, 446–455 (2016).

Ellahi, R., Zeeshan, A. & Hassan, M. Particle shape effects on Marangoni convection boundary layer flow of a nanofluid. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Heat Fluid Flow 26(7), 2160–2174 (2016).

Sheikholeslami, M., Zia, Q. M. & Ellahi, R. Effect of induced magnetic field on free convective heat transfer of nanofluid considering KKL correlation. Appl. Sci. 6, 324 (2016).

Lund, L. A. et al. Stability analysis and multiple solution of Cu–Al2O3/H2O nanofluid contains hybrid nanomaterials over a shrinking surface in the presence of viscous dissipation. J. Market. Res. 9(1), 421–432 (2020).

Ali Lund, L., Ching, D. L. C., Omar, Z., Khan, I. & Nisar, K. S. Triple local similarity solutions of Darcy-Forchheimer Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flow of micropolar nanofluid over an exponential shrinking surface: Stability analysis. Coatings 9(8), 527 (2019).

Khan, U., Zaib, A., Khan, I. & Nisar, K. S. Activation energy on MHD flow of titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) nanoparticle along with a cross flow and streamwise direction with binary chemical reaction and non-linear radiation: Dual Solutions. J. Market. Res. 9(1), 188–199 (2020).

Abro, K. A., Gómez-Aguilar, J. F., Khan, I. & Nisar, K. S. Role of modern fractional derivatives in an armature-controlled DC servomotor. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 134(11), 553 (2019).

Ullah, I. et al. MHD slip flow of Casson fluid along a nonlinear permeable stretching cylinder saturated in a porous medium with chemical reaction, viscous dissipation, and heat generation/absorption. Symmetry 11(4), 531 (2019).

Nisar, K. S., Khan, U., Zaib, A., Khan, I. & Morsy, A. A novel study of radiative flow involving micropolar nanoliquid from a shrinking/stretching curved surface including blood gold nanoparticles. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135(10), 1–19 (2020).

Jhangeer, A. et al. Lie analysis, conservation laws and travelling wave structures of nonlinear Bogoyavlenskii–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation. Results Phys. 19, 103492 (2020).

Raza, A. et al. A structure preserving numerical method for solution of stochastic epidemic model of smoking dynamics. CMC-Comput. Mater. Continua 65(1), 263–278 (2020).

Sheikh, N. A. et al. A generalized model for quantitative analysis of sediments loss: A Caputo time fractional model. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 33(1), 101179 (2021).

Saqib, M. et al. Heat transfer in MHD flow of maxwell fluid via fractional Cattaneo-Friedrich model: a finite difference approach. Comput. Mater. Continua 65(3), 1959–1973 (2020).

Ali, F., Ahmad, Z., Arif, M., Khan, I. & Nisar, K. S. A time fractional model of generalized Couette flow of couple stress nanofluid with heat and mass transfer: Applications in engine oil. IEEE Access 8, 146944–146966 (2020).

Agrawal, P. et al. Lie similarity analysis of MHD flow past a stretching surface embedded in porous medium along with imposed heat source/sink and variable viscosity. J. Market. Res. 9(5), 10045–10053 (2020).

Wang, C. Y. Flow due to a stretching boundary with partial slip–-an exact solution of the Navier-Stokes equations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 57(17), 3745–3747 (2002).

Pak, B. C. & Cho, Y. I. Hydrodynamic and heat transfer study of dispersed fluids with submicron metallic oxide particles. Exp. Heat Transfer Int. J. 11(2), 151–170 (1998).

Wang, X., Xu, X. & Choi, S. U. Thermal conductivity of nanoparticle-fluid mixture. J. Thermophys. Heat Transfer 13(4), 474–480 (1999).

Xuan, Y. & Li, Q. Heat transfer enhancement of nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 21(1), 58–64 (2000).

Li, Q. & Xuan, Y. Experimental investigation of transport properties of nanofluids. Heat Transfer Sci. Technol. 2000, 757–762 (2000).

Kakaç, S. & Pramuanjaroenkij, A. Review of convective heat transfer enhancement with nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 52(13–14), 3187–3196 (2009).

Wong, K. V. & De Leon, O. Applications of nanofluids: current and future. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2, 519659 (2010).

Noghrehabadi, A., Pourrajab, R. & Ghalambaz, M. Effect of partial slip boundary condition on the flow and heat transfer of nanofluids past stretching sheet prescribed constant wall temperature. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 54, 253–261 (2012).

Bachok, N., Ishak, A. & Pop, I. Flow and heat transfer characteristics on a moving plate in a nanofluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 55(4), 642–648 (2012).

Zaimi, K., Ishak, A. & Pop, I. Stretching surface in rotating viscoelastic fluid. Appl. Math. Mech. 34(8), 945–952 (2013).

Wahid, N. S., Md Arifin, N., Turkyilmazoglu, M., Hafidzuddin, M. E. H., & Abd Rahmin, N. A. MHD hybrid Cu-Al2O3/water nanofluid flow with thermal radiation and partial slip past a permeable stretching surface: analytical solution. In Journal of Nano Research (Vol. 64, pp. 75–91). Trans Tech Publications Ltd. (2020).

Turkyilmazoglu, M. Suspension of dust particles over a stretchable rotating disk and two-phase heat transfer. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 127, 103260 (2020).

Turkyilmazoglu, M. Wall stretching in magnetohydrodynamics rotating flows in inertial and rotating frames. J. Thermophys. Heat Transfer 25(4), 606–613 (2011).

Mukhopadhyay, S. MHD boundary layer flow and heat transfer over an exponentially stretching sheet embedded in a thermally stratified medium. Alex. Eng. J. 52(3), 259–265 (2013).

Gowda, R. P. et al. Thermophoretic particle deposition in time-dependent flow of hybrid nanofluid over rotating and vertically upward/downward moving disk. Surf. Interfaces 22, 100864 (2021).

Jayadevamurthy, P. G. R., Rangaswamy, N. K., Prasannakumara, B. C., & Nisar, K. S. Emphasis on unsteady dynamics of bioconvective hybrid nanofluid flow over an upward–downward moving rotating disk. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. (2020).

Kotresh, M. J., Ramesh, G. K., Shashikala, V. K. R. & Prasannakumara, B. C. Assessment of Arrhenius activation energy in stretched flow of nanofluid over a rotating disc. Heat Transf. 50(3), 2807–2828 (2021).

Radhika, M. et al. The flow of fluid-particle suspension between two rotating stretchable disks with the effect of the external magnetic field. Phys. Scr. 96(1), 015214 (2020).

Gireesha, B. J., Shankaralingappa, B. M., Prasannakumar, B. C. & Nagaraja, B. MHD flow and melting heat transfer of dusty Casson fluid over a stretching sheet with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model. Int. J. Ambient Energy 43(1), 2931–2939 (2022).

Agrawal, P. et al. Magneto Marangoni flow of γ− AL2O3 nanofluids with thermal radiation and heat source/sink effects over a stretching surface embedded in porous medium. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 23, 100802 (2021).

Khan, U., Zaib, A., Khan, I. & Nisar, K. S. Dual solutions of nanomaterial flow comprising titanium alloy (Ti 6 Al 4 V) suspended in Williamson fluid through a thin moving needle with nonlinear thermal radiation: Stability scrutinization. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–15 (2020).

Iqbal, M. S. et al. Impact of induced magnetic field on thermal enhancement in gravity driven Fe3O4 ferrofluid flow through vertical non-isothermal surface. Results Phys. 19, 103472 (2020).

Chabani, I., Mebarek-Oudina, F. & Ismail, A. A. I. MHD flow of a hybrid nano-fluid in a triangular enclosure with zigzags and an elliptic obstacle. Micromachines 13(2), 224 (2022).

Shoaib, M. et al. Numerical investigation for rotating flow of MHD hybrid nanofluid with thermal radiation over a stretching sheet. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–15 (2020).

Shoaib, M. et al. A stochastic numerical analysis based on hybrid NAR-RBFs networks nonlinear SITR model for novel COVID-19 dynamics. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 202, 105973 (2021).

Butt, Z. I., Ahmad, I., Shoaib, M., Ilyas, H. & Raja, M. A. Z. Electro-magnetohydrodynamic impact on Darrcy-Forchheimer viscous fluid flow over a stretchable surface: Integrated intelligent Neuro-evolutionary computing approach. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 137, 106262 (2022).

Shoaib, M., Naz, S., Raja, M. A. Z., Aslam, S., Ahmad, I., & Nisar, K. S. A design of soft computing intelligent networks for MHD Carreau nanofluid model with thermal radiation. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B, 2250192 (2022).

Ilyas, H., Ahmad, I., Raja, M. A. Z., Tahir, M. B. & Shoaib, M. Neuro-intelligent mappings of hybrid hydro-nanofluid Al2O3–Cu–H2O model in porous medium over rotating disk with viscous dissolution and Joule heating. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 46(55), 28298–28326 (2021).

Hou, E. et al. Entropy generation and induced magnetic field in pseudoplastic nanofluid flow near a stagnant point. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–25 (2021).

Hussain, A. et al. Mathematical analysis of hybrid mediated blood flow in stenosis narrow arteries. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1–10 (2022).

Rehman, A., Hussain, A. & Nadeem, S. Physical aspects of convective and radiative molecular theory of liquid originated nanofluid flow in the existence of variable properties. Phys. Scr. 96(3), 035219 (2021).

Rehman, A., Hussain, A., & Nadeem, S. Assisting and opposing stagnation point pseudoplastic nano liquid flow towards a flexible Riga sheet: a computational approach. Math. Probl. Eng (2021).

Haider, Q., Hussain, A., Rehman, A., Ashour, A. & Althobaiti, A. Mass and heat transport assessment and nanomaterial liquid flowing on a rotating cone: A numerical computing approach. Nanomaterials 12(10), 1700 (2022).

Nadeem, S., Ur Rehman, A., Mehmood, R. & Adil Sadiq, M. Partial slip effects on a rotating flow of two phase nano fluid over a stretching surface. Curr. Nanosci. 10(6), 846–854 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hussain, A., Akkurt, N., Rehman, A. et al. Transportation of thermal and velocity slip factors on three-dimensional dual phase nanomaterials liquid flow towards an exponentially stretchable surface. Sci Rep 12, 18595 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21966-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21966-y