Abstract

In this study, the necessity of radiotherapy (RT) for hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after breast-conserving surgery (BCS) was investigated. The data of hormone receptor-negative invasive breast cancer patients who underwent BCS were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from 2010 to 2015. All patients were separated into two groups, namely, the RT group and the no radiotherapy (No RT) group. The 3- and 5-year overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) rates were compared between the No RT and RT groups after propensity score matching (PSM). The nomograms for predicting the survival of patients were constructed from variables identified by univariate or multivariate Cox regression analysis. A total of 2504 patients were enrolled in the training cohort, and 630 patients were included in the validation cohort. After PSM, 738 patients were enrolled in the No RT group and RT group. We noted that RT can improve survival in hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients who undergo BCS. Based on the results of multivariate Cox analysis, age, race, tumour grade, receipt of RT and chemotherapy, pathological T stage, N status, M status and HER2 status were linked to OS and CSS for these patients, and nomograms for predicting OS and CSS were constructed and validated. Moreover, RT improved OS and CSS in hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients who underwent BCS. In addition, the proposed nomograms more accurately predicted OS and CSS for hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of breast cancer increases as age increases, and a growing number of breast cancer patients at diagnosis are over 70 years old1,2. The prevalence of breast conserving surgery (BCS) has recently increased, and radiotherapy (RT) is the standard treatment recommended for breast cancer patients after BCS3,4,5. However, the use of RT for older patients who undergo BCS has provoked heat debate. The evidence for the recommendation of RT was from clinical trials with an underrepresentation of older patients6,7. In addition, reduced treatments may be feasible for older breast cancer patients according to prior study8. Thus, the recommendation of RT for older breast cancer patients after BCS is controversial and needs further investigation.

It is well established that RT decreases the risk of locoregional recurrence and has a survival benefit in terms of overall survival (OS)9. However, the decision to perform RT for older patients is challenging in clinical practice. RT-related adverse events were the primary reason for patients not receiving RT10,11. In addition, the life expectancy, frailty and comorbidities of older patients are essential factors that we must consider when the necessity of RT is determined. Therefore, personalized treatment strategies should be tailored for these patients based on the benefits and costs of RT. Accumulating evidence has shown that RT can improve the prognosis of breast cancer patients after BCS12,13. Many studies have indicated that RT could be omitted for breast cancer patients after BCS14,15. In addition, a series of studies have indicated that emerging therapeutic strategies may improve patient prognosis and prevent the need for RT, but many issues remain to be resolved16,17,18,19. These paradoxical results may be attributed to the different baseline characteristics and molecular subtypes of the study cohort. Therefore, more studies are needed to address these conflicting findings. To date, few studies have explored the effect of RT on hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS. Moreover, there are no guidelines on RT for hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS.

Hence, this study was conducted to examine the effect of RT on hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS by comparing OS and cancer-specific survival (CSS) between the RT group and the no radiotherapy (No RT) group. In addition, nomograms for predicting OS and CSS were constructed and validated to optimize treatment options.

Materials and methods

Study population

The study population was from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, and the data were obtained from the SEER database through SEER*Stat (version 8.4.0.1). Patients who met the following inclusion criteria were enrolled in this study: (1) female patients diagnosed with breast cancer between 2010 and 2015; (2) aged no less than 70 years; (3) negative for oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status; (4) underwent BCS; and (5) had breast cancer as the first primary malignancy. Patients who met the following exclusion criteria were excluded in this study: (1) male breast cancer patients; (2) unknown tumour grade, TNM stage, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) status and cause of death; (3) missing survival time or survival time of 0; and (4) received preoperative or intraoperative radiotherapy. Patients included in this study were randomly divided into a training cohort and a validation cohort at an 8:2 ratio.

Variables and definitions

Older patients were defined as patients who were no less than 70 years old20. The BCS was defined as surgery with codes ranging from 20 to 2421. No RT was defined as no/unknown or refused, and RT was defined as beam radiotherapy or combination of beam with implants or isotopes22. Many variables were collected in the present study, which included patient characteristics, baseline characteristics (i.e., age, sex, race, etc.), tumour features (i.e., tumour grade, T stage, HER2 status), therapy and survival information (i.e., type of surgery, survival status, survival months). These patients were staged based on the 7th AJCC staging system.

Development and validation of the nomogram

The variables obtained from the SEER database were screened by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to identify prognostic factors related to OS and CSS. Only the variables with significant differences detected by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were included to construct the predictive nomograms. The receiver operating characteristic (AUC) curve was utilized to assess the discriminatory ability of the nomograms. A calibration curve was used to compare the possibility predicted by the nomogram with the actual possibility. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical utility of the models and the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 26.0, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and R software (version 3.6.3) were utilized to conduct the statistical analysis. R software was used to generate graphs. A 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was implemented based on age, tumour grade, pathological T stage, N status, M status and HER2 status with a calliper width of 0.01. Categorical variables that are displayed as numbers and percentages were compared by the chi-square test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were employed to identify risk factors associated with survival. The Kaplan‒Meier method was used to plot OS and CSS curves compared by the log-rank test. The statistical threshold was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics declarations

The data are publicly available, the informed consent of patients and ethical approval were waived by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University.

Results

Patients baseline characteristics

A total of 3134 eligible patients were included in this study and divided into a training cohort (2504) and a validation cohort (630). The patients enrolled in the training cohort were divided into a non-RT group (759) and an RT group (1745) based on their history of adjuvant RT. There were significant differences in terms of age, T stage, N status, M status, HER2 status and number of patients who received chemotherapy (CT) between the two groups in the training group (all P < 0.05, Table 1). After PSM, no difference was noted in these parameters between the No RT and RT groups (all P > 0.05, Table 2).

Survival analysis

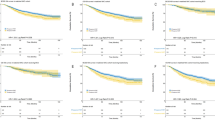

Survival analysis was conducted to explore the effect of RT on patients in the training cohort after PSM. The 3- and 5-OS (Fig. 1) and CSS (Fig. 2) were compared between the two groups stratified by different clinicopathological parameters. We found that there was a significant difference in OS between patients who were more than 70 years old, without CT, who had negative lymph nodes, who were grade I-IV, who were HER2-negative, and who had T1-2, M0 or M1 stage tumours between the No RT group and the RT group. However, OS did not differ between patients who received CT, those who had positive lymph nodes, those who had T3+4- and those who had HER2-positive tumours. Differences in CSS were noted between the two groups for patients older than 70 years, with or without CT, with negative and positive lymph nodes, with grade III + IV, HER2-negative or positive, and with T2-4 and M0 stage tumours. However, no significant differences were detected in grade I + II, T1 or M1 tumours after subgroup analysis.

Overall survival analysis of patients in the RT group and non-RT group according to stratified analysis. (A) Age between 70 and 80 years; (B) age more than 80 years; (C) Grade I–II; (D) Grade III–IV; (E) HER2-negative; (F) HER2-positive; (G) T1; (H) T2; (I) T3-4; (J) negative lymph node; (K) positive lymph node; (L) M0; (M) M1; (N) without CT; (O) with CT. RT, radiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy

Cancer specific survival analysis of patients in the RT group and non-RT group according to stratified analysis. (A) Age between 70 and 80 years; (B) age more than 80 years; (C) Grade I–II; (D) Grade III–IV; (E) HER2-negative; (F) HER2-positive; (G) T1; (H) T2; (I) T3-4; (J) negative lymph node; (K) positive lymph node; (L) M0; (M) M1; (N) without CT; (O) with CT.

Identification of prognostic factors for model construction

Prognostic factors were identified by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of the training cohort before PSM. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that older age, race, tumour grade, T stage, N status, M status, RT and CT status, HER2 status and marital status were linked to OS (Fig. 3A). Multivariate analysis revealed associations between these factors, except marital status, and OS (Fig. 3B). Notably, we discovered that older age, race, tumour grade, T stage, N status, M status, history of RT and CT, HER2 status and marital status were related to CSS according to univariate Cox regression analysis (Fig. 4A). Similarly, multivariate Cox regression analysis uncovered that marital status was not related to CSS (Fig. 4B).

Construction and validation of nomograms

Nomograms for predicting the OS and CSS of hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS were constructed based on the independent predictors identified by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses (Fig. 5). ROC curves and calibration curves were utilized to clarify the performance of the nomograms. In the training cohort, the AUCs of the nomograms for predicting 3- and 5-year OS were 0.766 and 0.752, respectively (Fig. 6A), and the AUCs of the nomograms for predicting 3- and 5-year CSS were 0.789 and 0.761, respectively (Fig. 6B). In the validation cohort, the AUCs of the nomograms for predicting 3- and 5-year OS were 0.730 and 0.739, respectively (Fig. 6C), and the AUCs of the nomograms for predicting 3- and 5-year CSS were 0.797 and 0.807, respectively (Fig. 6D). These results indicated that the nomograms have excellent discriminatory ability. Additionally, we noted that the 3- and 5-year OS and CSS calibration curves were nearly close to the ideal curves (Fig. 7). The results from the calibration curves suggested good consistency between the predicted and actual probabilities of survival outcomes in the training and validation cohorts. DCA curves were employed to explore the clinical utility of the nomograms. As shown by the DCA curves (Fig. 8), our prediction models had greater net clinical benefits than did the AJCC 7th edition stage model, which demonstrated the better clinical applicability of the nomograms.

The time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves of the nomogram predicting (A) 3- and 5-year overall survival in the training cohort; (B) 3- and 5-year cancer specific survival in the training cohort; (C) 3- and 5-year overall survival in the validating cohort; (D) 3- and 5-year cancer specific survival in the validating cohort.

The calibration curves of the nomogram for predicting (A) 3- and 5-year overall survival in the training cohort; (B) 3- and 5-year cancer specific survival in the training cohort; (C) 3- and 5-year overall survival in the validating cohort; (D) 3- and 5-year cancer specific survival in the validating cohort.

Discussion

The findings of our study implied that RT could bring survival benefit for hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS. Besides, the data confirmed that RT was related to OS and CSS for the patients. Hence, these results suggested RT was vital for hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS. Additionally, the nomograms predicting OS and CSS were constructed to investigate the clinical benefit and guide decision of RT for these patients in this study.

It is widely known that RT is the standard treatment after BCS for breast cancer. However, the comorbidities and expected survival of elderly patients and improved treatment outcomes in patients with breast cancer make omitting RT reasonable and practical. Therefore, clarifying the effect of RT on hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS is crucial for guiding clinical practice. Previous studies have examined the benefit of RT for older breast cancer patients and have shown no survival benefit from RT for older breast cancer patients23,24. In contrast to previous findings, the results indicated that RT can improve survival in older patients with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer after BCS. This may be attributed to the different study populations. They focused on early-stage and hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients, while we included only hormone receptor-negative patients. In addition, hormone receptor-negative breast cancer may exhibit more aggressive biological behaviours and may benefit from RT. However, the subgroup analysis indicated that RT did not improve survival in some patients, which may be attributed to the small sample size of the study cohort. More studies are warranted to confirm our results. Overall, the application and benefit of RT for older breast cancer patients may depend on tumour biology, tumour stage and molecular subtype25,26. As a consequence, the recommendation for RT should be made through comprehensive evaluation of patients.

In addition, the dose and form of RT may help alleviate concerns about RT-related adverse events and deserve more attention. An optimal dose and form of RT that decreases the incidence of adverse events may be a way to address this dilemma27,28,29. In addition, great breakthroughs in targeted therapy and immunotherapy for breast cancer have been made in recent years, providing a promising future30,31. This progress may make the omission of RT feasible. Based on various clinicopathological characteristics and advances in treatment strategies, appropriate decisions regarding RT should be made to avoid undertreatment or overtreatment. Hence, we constructed prognostic nomograms to help develop clinical strategies and predict patient prognosis.

In this study, we identified 9 risk factors to construct prognostic nomograms, which made the results highly reliable compared with those of the TNM stage system. Consistent with a previous study, we noted that the prognosis tends to worsen as age increases32,33. Generally, tumour grade is a crucial prognostic factor for breast cancer34. We also concluded that tumour grade was linked to prognosis for these patients. In addition, we found that HER2-positive patients had better favourable survival than HER2-negative patients, which was consistent with the findings of a prior study35. This may be because compared with HER2-positive patients, HER2-negative patients lack therapeutic targets. It is believed that T stage, N stage and M stage are linked to OS and CSS, and we draw conclusions similar to those of the studies of Fan’s and Lin’s36,37. Adjuvant RT and CT have been demonstrated to be effective at reducing the recurrence of breast cancer and improving patient prognosis38,39,40. In accordance with previous studies, we noted that the use of RT and CT was related to better OS and CSS. This is the first prognostic model for predicting OS and CSS in hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS. From the predictive nomograms, we confirmed that RT was linked with oncologic outcomes, which emphasized RT for patients. Additionally, the nomograms may help evaluate the prognosis and tailor personal treatment strategies for hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS.

However, there exists some limitations in current study. First, our study lacks external validation group to validate our results. Future efforts will seek to confirm our conclusion by utilizing other study cohorts. Second, several variables such as Ki-67, lymphovascular invasion and information about disease recurrence, etc. are not available in SEER database, which may confound the statistical results of the study and hamper predictive power of the nomograms. Therefore, the conclusions should be interpreted with great caution. Third, the SEER database does not provide detailed information regarding targeted therapy, dose of RT and CT, and immunotherapy, which could affect prognosis and consequently preciseness of the nomograms. Moreover, the inevitability of selective bias comes from retrospective study. Further prospective randomized controlled trials are warranted to validate these results.

Conclusion

RT can improve survival in hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after BCS. RT is suggested for these patients after BCS if health conditions permit. The predictive nomograms could help clinicians precisely grasp patient prognosis and make clinical decisions for patients after BCS.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Giaquinto, A. N. et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 524–541. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21754 (2022).

Paik, H.-J. et al. Characteristics and chronologically changing patterns of late-onset breast cancer in Korean women of age ≥ 70 years: A hospital based-registry study. BMC Cancer 22, 1261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-10295-y (2022).

Bundred, J. R. et al. Margin status and survival outcomes after breast cancer conservation surgery: prospectively registered systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 378, e070346. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-070346 (2022).

Kaczmarski, K. et al. Surgeon re-excision rates after breast-conserving surgery: A measure of low-value care. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 228, 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.043 (2019).

Kimball, C. C., Nichols, C. I., Vose, J. G. & Peled, A. W. Trends in lumpectomy and oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery in the US, 2011–2016. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25, 3867–3873. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6760-7 (2018).

Townsley, C. A., Selby, R. & Siu, L. L. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 3112–3124 (2005).

van de Water, W. et al. Breast-conserving surgery with or without radiotherapy in older breast patients with early stage breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 21, 786–794. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3374-y (2014).

Bastiaannet, E. et al. Lack of survival gain for elderly women with breast cancer. Oncologist 16, 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0234 (2011).

Darby, S. et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 378, 1707–1716. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61629-2 (2011).

Meattini, I. et al. Overview on cardiac, pulmonary and cutaneous toxicity in patients treated with adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer 24, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-016-0694-3 (2017).

Wennstig, A. K. et al. Risk of coronary stenosis after adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. Strahlenther. Onkol. 198, 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-022-01927-0 (2022).

De la Cruz-Ku, G. et al. Does breast-conserving surgery with radiotherapy have a better survival than mastectomy? A meta-analysis of more than 1,500,000 patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29, 6163–6188. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-12133-8 (2022).

Kunkler, I. H., Williams, L. J., Jack, W. J. L., Cameron, D. A. & Dixon, J. M. Breast-conserving surgery with or without irradiation in early breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2207586 (2023).

Kim, Y.-J., Shin, K. H. & Kim, K. Omitting adjuvant radiotherapy for hormone receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer in old age: A propensity score matched SEER analysis. Cancer Res. Treat. 51, 326–336. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2018.163 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Radiotherapy refusal in breast cancer with breast-conserving surgery. Radiat. Oncol. Lond. Engl. 18, 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-023-02297-2 (2023).

Guven, D. C. et al. The association between albumin levels and survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 1039121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.1039121 (2022).

Rizzo, A., Cusmai, A., Acquafredda, S., Rinaldi, L. & Palmiotti, G. Ladiratuzumab vedotin for metastatic triple negative cancer: Preliminary results, key challenges, and clinical potential. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 31, 495–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2022.2042252 (2022).

Rizzo, A. et al. Hypertransaminasemia in cancer patients receiving immunotherapy and immune-based combinations: The MOUSEION-05 study. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 72, 1381–1394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-023-03366-x (2023).

Rizzo, A. et al. Immune-based combinations for metastatic triple negative breast cancer in clinical trials: Current knowledge and therapeutic prospects. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 31, 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2022.2009456 (2022).

Yazici, H., Esmer, A. C., Eren Kayaci, A. & Yegen, S. C. Gastrıc cancer surgery in elderly patients: Promising results from a mid-western population. BMC Geriatr. 23, 529. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04206-4 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. Comparative effectiveness of nipple-sparing mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery on long-term prognosis in breast cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1222651. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1222651 (2023).

Chen, J.-X. et al. The effects of postoperative radiotherapy on survival outcomes in patients under 65 with estrogen receptor positive tubular breast carcinoma. Radiat. Oncol. Lond. Engl. 13, 226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-018-1177-9 (2018).

Hughes, K. S. et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: Long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 2382–2387. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2615 (2013).

Kunkler, I. H., Williams, L. J., Jack, W. J. L., Cameron, D. A. & Dixon, J. M. Breast-conserving surgery with or without irradiation in women aged 65 years or older with early breast cancer (PRIME II): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71221-5 (2015).

Chowdhry, V. K. Omission of radiotherapy in older adults with early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 7, 1397–1398. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2404 (2021).

Speers, C. & Pierce, L. J. Postoperative radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for early-stage breast cancer: A review. JAMA Oncol. 2, 1075–1082. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5805 (2016).

Batumalai, V. et al. Variation in the use of radiotherapy fractionation for breast cancer: Survival outcome and cost implications. Radiother. Oncol. 152, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2020.07.038 (2020).

Fiorentino, A. et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy and hypofractionated volumetric modulated arc therapy for elderly patients with breast cancer: Comparison of acute and late toxicities. Radiol. Med. 124, 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-018-0976-2 (2019).

Peng, H. et al. Optimal fractionation and timing of weekly cone-beam CT in daily surface-guided radiotherapy for breast cancer. Radiat. Oncol. Lond. Engl. 18, 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-023-02279-4 (2023).

Emens, L. A. Breast cancer immunotherapy: facts and hopes. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3001 (2018).

Ye, F. et al. Advancements in clinical aspects of targeted therapy and immunotherapy in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 22, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01805-y (2023).

Chen, M.-T. et al. Comparison of patterns and prognosis among distant metastatic breast cancer patients by age groups: A SEER population-based analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 9254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10166-8 (2017).

Pu, C.-C., Yin, L. & Yan, J.-M. Risk factors and survival prediction of young breast cancer patients with liver metastases: A population-based study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1158759. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1158759 (2023).

Han, Y. et al. Prognostic model and nomogram for estimating survival of small breast cancer: A SEER-based analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer 21, e497–e505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2020.11.006 (2021).

Tseng, Y. D. et al. Biological subtype predicts risk of locoregional recurrence after mastectomy and impact of postmastectomy radiation in a large national database. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 93, 622–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.07.006 (2015).

Fan, Y., Wang, Y., He, L., Imani, S. & Wen, Q. Clinical features of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and development of a nomogram for predicting survival. ESMO Open 6, 100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100232 (2021).

Lin, S. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting survival of advanced breast cancer patients in China. Breast 53, 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.08.004 (2020).

Corradini, S. et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy after breast conserving surgery—a comparative effectiveness research study. Radiother. Oncol. 114, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2014.08.027 (2015).

McGale, P. et al. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 383, 2127–2135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60488-8 (2014).

Wu, Y. et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on the survival outcomes of elderly breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study based on SEER database. J. Evid. Based Med. 15, 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12506 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yaxiong Liu: study design, data collection, data analysis and manuscript writing; Jinsong Li, Honghui Li, Gongyin Zhang, Changwang Li and Changlong Wei: data collection and data analysis; Jinsheng Zeng: study design, manuscript revision and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Li, J., Li, H. et al. Radiotherapy is recommended for hormone receptor-negative older breast cancer patients after breast conserving surgery. Sci Rep 14, 21355 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66401-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66401-6