Abstract

Binding of Staphylococcus aureus protein A (SPA) to osteoblasts induces apoptosis and inhibits bone formation. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) have the ability to differentiate into bone, fat and cartilage. Therefore, it was important to analyze the molecular mechanism of SPA on osteogenic differentiation. We introduced transcript sequence data to screen out differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to SPA-interfered BMSC. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of DEGs was established to screen biomarkers associated with SPA-interfered BMSC. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to evaluate the ability of biomarkers to discriminate between two groups of samples. Finally, we performed GSEA and regulatory analysis based on biomarkers. We identified 321 DEGs. Subsequently, 6 biomarkers (Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap and Kif14) were identified by hubba algorithm in PPI. ROC analysis showed that six biomarkers could clearly discriminate between normal differentiated and SPA-interfered BMSC. Moreover, we found that these biomarkers were mainly enriched in the pyrimidine metabolism pathway. We also constructed '71 circRNAs-14 miRNAs-5 mRNAs' and '10 lncRNAs-5 miRNAs-2 mRNAs' networks. Kntc1 and Asf1b genes were associated with rno-miR-3571. Nek2 and Asf1b genes were associated with rno-miR-497-5p. Finally, we found significantly lower expression of six biomarkers in the SPA-interfered group compared to the normal group by RT-qPCR. Overall, we obtained 6 biomarkers (Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap, and Kif14) related to SPA-interfered BMSC, which provided a theoretical basis to explore the key factors of SPA affecting osteogenic differentiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteomyelitis is one of the most challenging and difficult diseases in orthopedics. Osteomyelitis can easily induce bone defects, bone nonunion, and other related diseases, leading to limb dysfunction, amputation, and even life-threatening, seriously threatening the physical and mental health of patients1. Therefore, it is important to thoroughly investigate the mechanism related to osteomyelitis and bone defects. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogenic microorganism in osteomyelitis, which can cause increased inflammation and progressive bone destruction2. SPA, expressed in most S. aureus, is an important virulence factor in the cell wall of S. aureus that interacts with human immunoglobulins3. When SPA binds to osteoblasts, it has been reported to induce apoptosis and cell death, thereby inhibiting bone formation and mineralization4.

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) are considered a promising cellular resource and potential therapeutic tool for improving graft function and pathological recovery in a variety of diseases5,6. The development of osteomyelitis with bone defects is closely related to the reduced osteogenic differentiation capacity of BMSCs. It was found that during the development of osteomyelitis, SPA not only directly stimulates the apoptosis of osteoblasts in the focal area, which in turn causes bone destruction and bone loss in the focal area, but also downregulates the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs and upregulates their lipogenic differentiation ability. However, the decrease in the differentiation ability of BMSCs into osteoblasts directly affects osteogenesis and bone union, ultimately leading to infected bone non-union or the development of bone defects7. Interactions of chemokines and chemokine receptors mediate the migration of mesenchymal stem cells to the injured site in the brain after hypoglossal nerve injury, suggesting that SPA plays a key role in the development of osteomyelitis8. Therefore, an in-depth study of the causes of reduced osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under the effect of SPA is important for the treatment of osteomyelitis with bone defects.

In our previous study, we found that the occurrence of infectious bone defects is related to the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, and SPA inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, but the specific mechanism of action is unknown. In this study, by constructing an osteogenic differentiation cell model of BMSCs under the effect of SPA and performing bioinformatics analysis, we identified 6 biomarkers (Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap and Kif14) related to SPA-interfered BMSC, which laid a theoretical foundation for exploring the key factors of SPA affecting osteogenic differentiation. And we tried to explore the specific mechanism of action by constructing non-coding RNA interaction network. This is a new theoretical basis and research direction for further understanding and treatment of osteomyelitis and bone defects.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and sequencing

All cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and osteogenically differentiated for 14 d. Two groups were established, the experimental group treated with SPA (1 mg/mL)9 (Aladdin Corporation, Shanghai, China) and the control group not treated with SPA, each consisting of 3 samples. Total RNA was extracted from all samples using TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Austin, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA quality and integrity were assessed using an RNA quality assay. Reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA was performed using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). The subsequent steps involved precise end filling of the cDNA fragments to create blunt ends, followed by the addition of an 'A' base at the 3' ends (A-tailing) to facilitate adapter ligation. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was performed using junction primers to selectively enrich the cDNA fragments of interest. These carefully prepared cDNA libraries underwent rigorous quality control prior to sequencing on the Illumina platform, allowing for comprehensive transcriptomic analysis.

Data processing

The whole transcript sequence data of 6 BMSCs form Rattus norvegicus was obtained, of which 3 normal differentiated and 3 SPA interfered samples. The raw sequencing reads were processed using Trimmomatic (version 0.36) to remove adapters and low quality sequences, resulting in clean data. The clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using hisat2 (version 2.1.0). Alignment results were quantified using samtools (version 0.1.19) and RNA was quantified based on genomic positions annotated in the reference. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the processed data using the 'scatterplot3d' package in R to visualize clustering and variability between different sample groups.

Analysis of differential genes

The ‘Deseq2’ R package10 was applied to mine differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between normal differentiated group and SPA interfered group. The P value < 0.05 & |log2fold change (FC)|> 2.5 was determined as the signifcance criteria. Volcano plot and heatmap were applied to show DEGs. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed using ‘clusterProfiler’ and KEGG pathway database was used for pathway enrichment (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/)11,12,13,14. p < 0.05 was used as screening criteria.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network

PPI network which depicted the interactions among DEGs was generated using search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes (STRING) website (https://string-db.org). Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) algorithm of cytoscape plug-in was applied to screen core gene cluster15. Subsequently, we applied 4 distinct centrality measures provided by cytohubba plug-in: degree, edge filtered component (EPC), betweenness and closeness. These centrality measures are widely recognized for their utility in network analysis: 1. Degree centrality reflects the number of connections a node has and is commonly used to pinpoint nodes with high direct influence within the network. 2. EPC estimates the influence of a node based on the connection strength with its neighbors, highlighting genes capable of connecting various network regions. 3. Betweenness centrality considers the number of shortest paths passing through the node, thus identifying gene nodes that serve as critical bridges within the network structure. 4. Closeness centrality reveals nodes that can quickly interact with other nodes due to their shorter path lengths to all other nodes in the network. Eventually, the biomarkers for this study were obtained by overlapping 10 genes with the highest scores.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

ROC curve was plotted to evaluate the ability of biomarkers to distinguish normal differentiated cells from SPA-interfered cells by ‘pROC’ package16. GSEA was conducted to explore the potential GO items and KEGG pathways associated with biomarkers through ‘clusterProfiler’ package17. p. adjust < 0.05 was used as screening criteria.

The circRNA/lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network construction

In order to explore the regulatory relationship, miRDB (https://mirdb.org/index.html) was utilized to forecast the miRNAs of biomarkers. circRNAs that interacted with miRNAs were predicted through the miranda (www.microrna.org / microrna / home.do) database. Further, circRNAs with consistent expression trends with biomarkers were applied for subsequent analysis. The same method was yielded to obtain the lncRNAs. Cytoscape software18 was applied to optimize the ‘circRNA-miRNA-mRNA’ and ‘lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA’ network.

The analysis of the expression of biomarkers

In order to confirm the expression of biomarkers, we implemented Reverse Transcription quantitative-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR). The 5 normal SD-BMSC1 cells and 5 intervention cells were obtained with the consent from The Affiliated Hospital of Yunnan University, and this study was approved by the ethics committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Yunnan University. RNA extraction was performed by homogenizing the cells in TRIzol reagent, followed by phase separation with chloroform, RNA precipitation with isopropanol, washing with 75% ethanol, and resuspension in RNase-free water. The RNA quality and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Subsequently, RT-qPCR was conducted using the 2 × Universal Blue SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Servicebio, Wuhan, China), following the manual's guidelines. The PCR amplification was performed in a real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, USA), with the thermal cycling conditions set as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. The primer sequences for PCR were tabulated in Table 1. GAPDH was used as an internal reference gene, and the expression was calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method19.

Statistical analysis

All P values of statistical results were based on two-sided statistical tests, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of DEGs related to SPA interfered BMSC

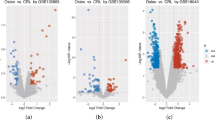

Using the mouse reference genome alignment, the mapping rate of all samples was above 88.15%, indicating that the quality of sequencing was very good. PCA analysis suggested that there was obvious separation between the two sample groups (Fig. 1A). 321 DEGs were identified in SPA interfered vs normal differentiated group, including 260 down-regulated and 61 up-regulated genes (Fig. 1B, C). To further probe the function of the DEGs, functional enrichment analysis was conducted. GO results indicated that these DEGs were principally involved in ‘mitotic nuclear division’, ‘chromosome separation’ and ‘nuclear division’ (Fig. 1D). Additionally, the KEGG analysis demonstrated that these DEGs were mainly enriched in the ‘Complement and coagulation cascades’ and ‘p53 signaling pathway’ (Fig. 1E).

Identification of DEGs and functional enrichment analysis. (A) PCA analysis of normal differentiated group and SPA interfered group. (B, C) The volcano map (B) and heat map (C) of DEGs between normal differentiated group and SPA interfered group. (D, E) The GO terms (D) and KEGG pathways (E) enriched in DEGs. KEGG pathway database was used for pathway enrichment (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/). DEGs, differentially expressed genes; PCA, principal component analysis; SPA, Staphylococcus aureus protein A; GO, gene ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Screening of biomarkers associated with SPA interfered BMSC

In order to explore the interaction regulation relationship, the PPI network of the DEGs was constructed, including 295 nodes and 1423 edges (Fig. 2A). We then screened an important gene cluster, which include 48 genes (Fig. 2B). After that, six biomarkers associated with SPA interference, including Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap and Kif14, were obtained by overlapping 10 genes with the highest scores based on four algorithms in the 48 gene cluster (Fig. 2C). At the transcription level, we observed lower expression of Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap, and Kif14 in SPA interfered group compared to the normal differentiated group (Fig. 2D). The area under the curve (AUC) values of biomarkers were all 1, indicating an excellent ability to distinguish normal differentiated cells from SPA-interfered cells (Fig. 2E).

Identification of biomarkers for SPA interfered BMSC. (A) The PPI network of DEGs. (B) The interaction of the important gene cluster. (C) The Venn diagram of six biomarkers. (D) The expression of biomarkers in normal differentiated group and SPA interfered group. (E) The ROC curves of biomarkers. BMSC, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; PPI, protein–protein interaction; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Functional enrichment analysis

To further study the potential roles of Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap and Kif14 related to SPA interference in BMSC, we performed single-gene GSEA on biomarkers. The results showed that Cenpf was mainly enriched in the ‘regulation of autophagy’ and ‘Lysosome’ (Fig. 3A, B). Kntc1 and Nek2 were mainly related to the ‘autophagosome’ and ‘Pyrimidine metabolism’ (Fig. 3C–F). Asf1b and Troap was mainly enriched in the ‘process utilizing autophagic mechanism’ and ‘Biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars’ (Fig. 4A–D). Kif14 was mainly enriched in the ‘macroautophagy’ and ‘Pyrimidine metabolism’ (Fig. 4E, F).

Functional enrichment analysis. GO terms and KEGG pathways enriched in Cenpf (A, B), Kntc1 (C, D), Nek2 (E, F). KEGG pathway database was used for pathway enrichment (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/).

Functional enrichment analysis. GO terms and KEGG pathways enriched in Asf1b (A, B), Troap (C, D), and Kif14 (E, F). KEGG pathway database was used for pathway enrichment (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/).

Construction of the regulatory network

To explore the regulatory mechanism of biomarkers associated with SPA interfered BMSC, 71 circRNAs-14 miRNAs-5 mRNAs network was constructed (Fig. 5A). The network had 90 nodes and 107 edges, in which Kntc1, and Asf1b genes were associated with rno-miR-3571. Additional, 10 lncRNAs-5 miRNAs-2 mRNAs network was constructed (Fig. 5B).The network had 34 nodes and 17 edges, in which Nek2, and Asf1b genes were associated with rno-miR-497-5p.

Exploration of regulatory mechanism for biomarkers. (A) The network of circRNA-miRNAs-mRNA.The green squares represent circRNAs, orange squares represent miRNAs, and red circles represent mRNA. (B) Construction of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network. Blue hexagons represent lncRNAs, orange squares represent miRNAs, and red circles represent mRNA. circRNA, circular RNA; miRNA, microRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

Experimental verification of marker expression level

We verified the expression in clinical cell samples by RT-qPCR, which in agreement with the results of the public database data analysis. The expression of Cenpf, Kntc1, Asf1b and Kif14 were notably reduced in clinical SPA interfered group versus normal group. However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups for Nek2 and Troap (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Our previous study and other related studies have shown that SPA can affect the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. In this study, bioinformatic analysis of transcriptome sequencing data revealed that the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under the effect of SPA caused the differential expression of molecular markers Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap and Kif14. And these molecular biomarkers formed a network of interactions with nRNA. There were few studies on this aspect.

Kinetochore-associated 1 (Kntc1) encodes a protein that is one of many involved in mechanisms that ensure proper chromosome segregation during cell division. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that Kntc1 was mainly associated with autophagosome and pyrimidine metabolism. Recent studies have suggested that mitogenic proteins may be potential biomarkers and may contribute to the development of human malignancies20. It has been frequently associated with tumors of the digestive and genitourinary systems21. It was shown that Kntc1 was highly expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues and was associated with poor prognosis, suggesting a key role for Kntc1 in HCC development22. Wnt signaling, MAPK signaling, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling, PI3K/Akt signaling, Hedgehog signaling, and other signaling pathways are closely related to osteogenic differentiation23,24,25. Kntc1 has been reported to function in a variety of diseases by participating in the PI3K/Akt pathway22, and we speculated that it may also be involved in the regulation of osteogenic differentiation in BMSCs. Kntc1 has been shown to play an important role in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway26, which has been extensively studied and shown to play a key regulatory role in osteogenic differentiation. Therefore, Kntc1 may regulate osteoblast differentiation and function through this pathway, a finding that is consistent with the performance of Kntc1 in our results.

Centromere protein F (Cenpf) was a protein-coding gene. Functional enrichment analysis showed that Cenpf was mainly enriched in "regulation of autophagy" and "lysosome". Overexpression of Cenpf was associated with the tumorigenesis of many human malignant tumors27,28,29. Moreover, Cenpf was a cancer stem cell (CSC)-specific marker gene, and the latter played a key role in promoting bone destruction30. Cenpf has a close relationship with the MAPK31,32 and Wnt33 signaling pathways. Antisilencing function 1b (Asf1b) had effects on cell proliferation, leading to abnormal nuclear structure and unique transcriptional features34, and was frequently associated with various malignancies35,36. According to the functional enrichment analysis, Asf1b was mainly enriched in "process using autophagic mechanism" and "nucleotide sugar biosynthesis". In addition, several studies have shown that Asf1b plays an important role in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway37,38,39. Never in mitosis gene A-related kinase 2 (Nek2) was highly associated with drug resistance, rapid recurrence and poor outcome in a variety of cancers40. Functional enrichment analysis showed that Nek2 was mainly related to "autophagosome" and "pyrimidine metabolism". It has been shown that Nek2 overexpression is associated with the development of bone damage41 and that it regulates osteoblast gene expression and affects osteoblast growth and activity42. In addition, Nek2 induced osteoclast differentiation and bone destruction via heparanase in multiple myeloma43. Nek2 has been reported to play an important regulatory role in MAPK44,45, Wnt/β-catenin46,47,48, PI3K/Akt49, and other signaling pathways.

Another study highlighted the regulatory role of Nek2 in the MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin pathways50. These pathways are also important in osteogenic differentiation. Nek2, as a key regulatory molecule, may promote osteoblast differentiation by affecting the activity of these pathways, which further validates the role of Nek2 in our study. Experimental evidence suggests that troponin-associated protein (Troap) plays a key role in regulating cell proliferation in several tumors51,52. One study found that Troap accelerated glioma progression through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway51. Finally, Kinesin family member 14 (Kif14) was a mitotic kinesin whose abnormal function was associated with developmental defects in brain and kidney as well as several cancers53. Functional enrichment analysis showed that Kif14 was mainly enriched in 'macroautophagy' and 'pyrimidine metabolism'. In addition, Kif14 was also active in signaling pathways such as Wnt signaling54,55, Hedgehog signaling56,57, and PI3K/Akt signaling58. To date, there have been no studies on the direct involvement of the above biomarkers in the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. These studies also suggest their possible cross-cutting roles in the regulation of osteogenic differentiation under the influence of SPA. Thus, the specific mechanisms of biomarkers such as Asf1b, Troap, and Kif14 in osteogenic differentiation need to be further investigated, but their importance in other cellular processes suggests that they may regulate osteogenic differentiation through complex networks and signaling cascades. In addition, the cited literature emphasizes that understanding the complex molecular interactions and signaling cascades in osteogenic differentiation is essential for the development of therapeutic approaches targeting bone-related diseases. Our findings contribute to this knowledge base by suggesting how SPA may regulate these processes through specific molecular markers. In conclusion, we suggest that future studies could further explore the specific mechanisms of these molecules in osteogenic differentiation to better understand the complex network of osteogenic differentiation and provide new ideas for the treatment of bone-related diseases.

To date, studies on the regulation of osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by non-coding RNAs have been reported. However, there were few studies on the regulation of osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by non-coding RNAs in SPA mimicking inflammatory environment. From the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network in this study, it could be found that miR-497-5p and miR-322-5p had an action relationship with both Asf1b and Nek2. And a study showed that miR-497-5p was significantly downregulated in bone tissue of aging and osteoporosis mouse models and upregulated during osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells. Overexpression of miR-497-5p promoted osteoblast differentiation and mineralization59. In addition, a study showed that miR-322-5p was significantly downregulated during osteogenic differentiation of rat BMSCs60. Second, miR-455-3p was shown to promote osteogenic differentiation, which may be related to fracture healing61, while the present study found a regulatory relationship between miR-455-3p and Troap. Finally, miR-207 was significantly downregulated during FK506-induced osteogenic differentiation of rat BMSCs, while the present study showed an association between miR-207 and Nek262. In conclusion, the present study identified some potential molecular networks of action, the potential significance of which should be clarified by further studies.

Bioinformatics has been widely used for differential analysis of osteogenic differentiation at the genomic level, allowing the identification of functional pathways of DEGs associated with osteogenic differentiation in BMSC. In this study, bioinformatics analysis was performed to obtain some key biomarkers hypothesized to be involved in the regulation of osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in an inflammatory environment. It provides some clues to explore the key factors of SPA affecting osteogenic differentiation. There were some shortcomings in this study that we would like to highlight. First, we used SPA to simulate the inflammatory environment, which is somewhat different from the real inflammatory environment observed in clinical settings. This simulation may not fully capture the complex interactions present in vivo. In addition, two of the biomarkers identified in our study were not successfully validated, which may be related to the quality of the samples or the limitations of our experimental conditions. This discrepancy highlights the need for further investigation using a larger and more diverse sample set to ensure the robustness of our findings. We also recognize that the bioinformatics approach, while powerful, has its own limitations. It provides a broad overview but lacks the granularity that detailed experimental validation can provide. We are committed to clarifying the roles of these biomarkers through future experiments and to analyzing their molecular mechanisms of action in depth. This will require more sophisticated in vitro and in vivo models to closely mimic physiological conditions and verify the relevance of our bioinformatics predictions.

Conclusion

Overall, we obtained 6 biomarkers (Cenpf, Kntc1, Nek2, Asf1b, Troap and Kif14) related to SPA interfered BMSC, which laid a theoretical foundation for exploring the key factors of SPA affecting osteogenic differentiation.

Data availability

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2021) in National Genomics Data Center (Nucleic Acids Res 2022), China National Center for Bioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA: CRA014184) that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.

References

Zeller, J. L., Burke, A. E. & Glass, R. M. JAMA patient page. Osteomyelitis. JAMA 299(7), 858 (2008).

Kavanagh N, Ryan EJ, Widaa A, Sexton G, Fennell J, O'Rourke S, et al. Staphylococcal osteomyelitis: disease progression, treatment challenges, and future directions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31(2).

Widaa, A., Claro, T., Foster, T. J., O’Brien, F. J. & Kerrigan, S. W. Staphylococcus aureus protein A plays a critical role in mediating bone destruction and bone loss in osteomyelitis. PLoS ONE 7(7), e40586 (2012).

Claro, T. et al. Staphylococcus aureus protein A binds to osteoblasts and triggers signals that weaken bone in osteomyelitis. PLoS ONE 6(4), e18748 (2011).

Huang, Y. et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in premature ovarian failure: Mechanisms and prospects. Front Immunol. 13, 997808 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells attenuate liver allograft rejection may via upregulation PD-L1 expression through downregulation of miR-17-5p. Transpl Immunol. 51, 21–29 (2018).

Jiang, X. et al. bFGF-Modified BMMSCs enhance bone regeneration following distraction osteogenesis in rabbits. Bone. 46(4), 1156–1161 (2010).

Ji, J. F., He, B. P., Dheen, S. T. & Tay, S. S. Interactions of chemokines and chemokine receptors mediate the migration of mesenchymal stem cells to the impaired site in the brain after hypoglossal nerve injury. Stem cells. 22(3), 415–427 (2004).

Wen, H., Chen, Z., Cui, Y. & Xu, Y. LncRNA NONHSAT009968 inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of hBMMSCs in SA-induced inflammation via Wnt3a. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 577(Null), 24–31 (2021).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15(12), 550 (2014).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics. 16(5), 284–287 (2012).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592 (2023).

Chen, X. M. et al. Novel findings from determination of common expressed plasma exosomal microRNAs in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis vulgaris, rheumatoid arthritis, and gouty arthritis. Discovery Med. 28(151), 47–68 (2019).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Kumar L, M EF. Mfuzz: A software package for soft clustering of microarray data. Bioinformation. 2007;2(1):5–7.

Ru, Y. et al. The multiMiR R package and database: Integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(17), e133 (2014).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25(4), 402–408 (2001).

Zhang, W. et al. SYT7 regulates the progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia through interacting and regulating KNTC1. Biomarker Res. 11(1), 58 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. shRNA-mediated knockdown of KNTC1 inhibits non-small-cell lung cancer through regulating PSMB8. Cell Death Dis. 13(8), 685 (2022).

Tong, H., Liu, X., Peng, C., Shen, B. & Zhu, Z. Silencing of KNTC1 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cells progression via suppressing PI3K/Akt pathway. Cell Signal. 101, 110498 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Nanoporous titanium implant surface promotes osteogenesis by suppressing osteoclastogenesis via integrin β1/FAKpY397/MAPK pathway. Bioact Mater. 8, 109–123 (2022).

Yi, C., Liu, D., Fong, C. C., Zhang, J. & Yang, M. Gold nanoparticles promote osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells through p38 MAPK pathway. ACS Nano. 4(11), 6439–6448 (2010).

Wang, T. et al. Magnetofection of miR-21 promoted by electromagnetic field and iron oxide nanoparticles via the p38 MAPK pathway contributes to osteogenesis and angiogenesis for intervertebral fusion. J. Nanobiotechnol. 21(1), 27 (2023).

Li M, Shi X, Wu Y, Qi B, Zhang C, Wang B, et al. Corrigendum to "Pmepa1 knockdown alleviates SpA-induced pyroptosis and osteogenic differentiation inhibition of hBMSCs via p38MAPK/NLRP3 axis" [Int. Immunopharmacol. 124(Part A) (2023) 110843]. Int immunopharmacol. 2023;124(Pt A):111013.

Sun, J. et al. Overexpression of CENPF correlates with poor prognosis and tumor bone metastasis in breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 19, 264 (2019).

Lokody, I. Signalling: FOXM1 and CENPF: Co-pilots driving prostate cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 14(7), 450–451 (2014).

Aytes, A. et al. Cross-species regulatory network analysis identifies a synergistic interaction between FOXM1 and CENPF that drives prostate cancer malignancy. Cancer cell. 25(5), 638–651 (2014).

Pan, X. W. et al. Identification of a novel cancer stem cell subpopulation that promotes progression of human fatal renal cell carcinoma by single-cell RNA-seq analysis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16(16), 3149–3162 (2020).

Xu, P. et al. N6-methyladenosine modification of CENPF mRNA facilitates gastric cancer metastasis via regulating FAK nuclear export. Cancer Commun (London, England). 43(6), 685–705 (2023).

Zhang, M., Zhang, Q., Bai, J., Zhao, Z. & Zhang, J. Transcriptome analysis revealed CENPF associated with glioma prognosis. Math. Biosci. Eng. 18(3), 2077–2096 (2021).

Sánchez-Tilló, E. et al. The EMT activator ZEB1 promotes tumor growth and determines differential response to chemotherapy in mantle cell lymphoma. Cell Death Differ. 21(2), 247–257 (2014).

Corpet, A. et al. Asf1b, the necessary Asf1 isoform for proliferation, is predictive of outcome in breast cancer. Embo J. 30(3), 480–493 (2011).

Liu, X. et al. ASF1B promotes cervical cancer progression through stabilization of CDK9. Cell Death Dis. 11(8), 705 (2020).

Chen, Z., Ou, D., Huang, Z. & Shen, P. Identification of hsa_circ_0002024 as a prognostic competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) through the hsa_miR_129-5p/anti-silencing function 1B Histone Chaperone (ASF1B) axis in renal cell carcinoma. Bioengineered. 12(1), 6579–6593 (2021).

Han, G. et al. Knockdown of anti-silencing function 1B histone chaperone induces cell apoptosis via repressing PI3K/Akt pathway in prostate cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 53(5), 2056–2066 (2018).

Wang, K. et al. Involvement of elevated ASF1B in the poor prognosis and tumorigenesis in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 477(7), 1947–1957 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. ASF1b is a novel prognostic predictor associated with cell cycle signaling pathway in gastric cancer. J. Cancer. 13(6), 1985–2000 (2022).

Zhou, W. et al. NEK2 induces drug resistance mainly through activation of efflux drug pumps and is associated with poor prognosis in myeloma and other cancers. Cancer Cell. 23(1), 48–62 (2013).

Gu, X., Wang, Z. & Pan, Q. Overexpression of NIMA related kinase 2 in multiple myeloma and its relevance with disease features and prognosis to bortezomib treatment. J. Clin. Pharm. Therap. 47(10), 1690–1697 (2022).

Yang, J., Zhou, C., Wang, Y., Fan, X. & Jia, R. Multimodal therapy in the management of lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 19(1), 125 (2019).

Hao, M. et al. NEK2 induces osteoclast differentiation and bone destruction via heparanase in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 31(7), 1648–1650 (2017).

Di Agostino, S., Rossi, P., Geremia, R. & Sette, C. The MAPK pathway triggers activation of Nek2 during chromosome condensation in mouse spermatocytes. Development. 129(7), 1715–1727 (2002).

Zhang, M. X. et al. Effect of silencing NEK2 on biological behaviors of HepG2 in human hepatoma cells and MAPK signal pathway. Tumour Biol. 37(2), 2023–2035 (2016).

Xu, T. et al. Targeting NEK2 impairs oncogenesis and radioresistance via inhibiting the Wnt1/β-catenin signaling pathway in cervical cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.: CR. 39(1), 183 (2020).

Chen, Y., Wu, N., Liu, L., Dong, H. & Liu, X. microRNA-128-3p overexpression inhibits breast cancer stem cell characteristics through suppression of Wnt signalling pathway by down-regulating NEK2. J Cell Mol Med. 24(13), 7353–7369 (2020).

Zhou, J., Lai, J., Cheng, Y. & Qu, W. NEK2 serves as a novel biomarker and enhances the tumorigenicity of clear-cellrenal-cell carcinoma by activating WNT/β-catenin pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022, 1890823 (2022).

Das, T. K. et al. Centrosomal kinase Nek2 cooperates with oncogenic pathways to promote metastasis. Oncogenesis. 2(9), e69 (2013).

Wu, H., Cao, F., Zhou, W., Wang, G., Liu, G., Xia, T., et al. Long Noncoding RNA FAM83H-AS1 modulates SpA-inhibited osteogenic differentiation in human bone mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2020;40(5):null.

Zhao, Z. Q. et al. TROAP regulates cell cycle and promotes tumor progression through Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway in glioma cells. CNS Neurosci Ther. 27(9), 1064–1076 (2021).

Li, L. et al. TROAP switches DYRK1 activity to drive hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Cell Death Dis. 12(1), 125 (2021).

Benoit, M. et al. Structural basis of mechano-chemical coupling by the mitotic kinesin KIF14. Nature Commun. 12(1), 3637 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Molecular subtyping of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by large-scale transcriptional profiling: Characterization, therapeutic targets, and prognostic value. Front Genet. 13, 1033214 (2022).

Yang, T. et al. Sox17 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression by downregulation of KIF14 expression. Tumour Biol. 35(11), 11199–11207 (2014).

Pejskova, P., Reilly, M. L., Bino, L., Bernatik, O., Dolanska, L., Ganji, R. S., et al. KIF14 controls ciliogenesis via regulation of Aurora A and is important for Hedgehog signaling. J. Cell. Biol. 219(6) (2020).

Liu, J., Li, D., Zhang, X., Li, Y. & Ou, J. Histone demethylase KDM3A promotes cervical cancer malignancy through the ETS1/KIF14/Hedgehog axis. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 11957–11973 (2020).

Yang, T., Zhang, X. B. & Zheng, Z. M. Suppression of KIF14 expression inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression and predicts favorable outcome. Cancer Sci. 104(5), 552–557 (2013).

Ma, J., Lin, X., Chen, C., Li, S., Zhang, S., Chen, Z., et al. Circulating miR-181c-5p and miR-497–5p are potential biomarkers for prognosis and diagnosis of osteoporosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105(5) (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Comprehensive analysis of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks during osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. BMC Genomics. 23(1), 425 (2022).

Ma, H., Li, M., Jia, Z., Chen, X. & Bu, N. MicroRNA-455-3p promotes osteoblast differentiation via targeting HDAC2. Injury-int. J. Care Injured. 53(11), 3636–3641 (2022).

Zhang, J., Yu, X., Yu, Y. & Gong, Y. MicroRNA expression analysis during FK506-induced osteogenic differentiation in rat bone marrow stromal cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 16(1), 581–590 (2017).

Funding

This study was supported by the Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department Kunming Medical University Joint Special Project (No. 202201AY070001-274) and Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology Basic Research Top Level Project (No. 202401AT070455).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: HJW; methodology: SYZ; formal analysis: HGY; investigation: SYZ, HGY and HJW; resources: FYG; data curation: SYZ and HGY; writing-original draft preparation: HJW; writing-reviewing, and editing: FYG and SYZ; supervision: FYG; project administration: FYG. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, Hj., Zhu, Sy., Yang, Hg. et al. Investigation on the molecular mechanism of SPA interference with osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep 14, 15600 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66502-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66502-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hyperspectral magnetite grade based on characteristic band screening inversion study

Scientific Reports (2025)