Abstract

This work develops a dual-layer energy management (DLEM) model for a microgrid (MG) consisting of a community, distributed energy resources (DERs), and a grid. It ensures the participation of all these energy entities of MG in the market and their interaction with each other. The first layer performs the scheduling operation of the community with the goal of minimizing its net-billing cost and sends the obtained schedule to the DER operator and grid. Further, the second layer formulates a power scheduling algorithm (PSA) to minimize the net-operating cost of DERs and takes into account the load demand requested by the community operator (COR). This PSA aims to achieve optimal operation of MG by considering solar PV power, requested demand, per unit grid energy prices, and state of charge of the battery energy storage system of the DER layer. Moreover, to study the impact of electric vehicles (EVs) load programs on DLEM, the advanced probabilistic EV load profile model is developed considering practical and uncertain events. The EV load is modelled for grid to vehicle mode, and a new mode of EV operation is introduced, i.e., vehicle to grid with EV demand response strategy (V2G_DRS) mode. The solar PV and load demand data are obtained from the MG setup installed and buildings present at the university campus. However, a scenario reduction technique is used to deal with the uncertainties of the obtained data. In order to evaluate the efficacy of the developed DLEM, its results are compared to previously reported energy management models. The results reveal that DLEM is superior to the existing models as it decreases the net-billing cost of COR by 13% and increases the profit of the DER operator by 17%. Further, it is found that for the highest EV penetration, i.e., 30 EVs, the V2G_DRS mode of EV operation reduces the total energy imported by COR by 11.39% and the net-billing cost of COR by 7.88%. Therefore, it can be concluded that the proposed model with the introduced V2G_DRS mode of EV makes the operation of all the entities of MG more economical and sustainable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and motivation

Promoting energy generation using indigenous resources, especially renewable energy resources (RERs) and low-carbon technology, has gained immense popularity. Several countries have been working to shift to greener, more sustainable energy systems to eliminate the harmful environmental consequences of their existing energy systems. In this regard, at the 26th annual summit of COP (Conference of Parties), i.e., COP26, more than 200 countries pledged to keep temperature rises within 1.5 deg.C and to reach net zero emissions by 20501. It is suggested by the International Energy Agency (IEA) that this goal can be achieved by increasing the integrated installation of distributed energy resources (DERs) such as solar PV systems and energy storage systems (ESSs) and by more adoption of electric vehicles (EV)2. This integration of DERs and a set of loads is termed a microgrid (MG)3,4,5. It reflects that the MG has multiple energy entities, such as DERs, loads, and grid, which are responsible for its complete operation6,7. However, to achieve the economical and reliable operation of MG, it is necessary that each energy entity (DERs, loads, etc.) interacts with each other and individually participates in an energy management model.

In recent years, the load demand on the energy system has also increased with the construction of large-scale communities, which consist of groups of buildings and EV charging stations. They are major electricity consumers and can use DERs along with the grid to fulfill their power demand8,9,10. However, to attain substantial economic profit for the community owner, it is necessary to optimally manage their energy consumption (including buildings and EV loads) and energy exchanges with DERs and the grid. Further, due to the uncertain nature of renewable-based DERs, a scheduling strategy is required that minimizes their operating cost while fulfilling the load demand of the community.

Electric vehicles (EVs) have gained high attention as a green energy transportation in the past few years11. It can play a crucial role in the energy management of community load by optimally managing their charging time and the energy stored in their batteries12. By enabling the vehicle to grid (V2G) power transfer technology and implementing an EV-based demand response strategy (DRS), the community owner can obtain more financial benefits. But, due to the uncertain EV owner’s behavior, the efficient modeling of EV load profile for various EV operations becomes complicated. Therefore, to achieve effective energy scheduling for the communities, it is important to model the EV load profile (EVPL) while considering uncertain EV owners’ behavior for various EV modes.

Further, these aforementioned challenges have motivated the authors to simultaneously deal with a complex problem of achieving energy management of individual entities of MG, i.e., DERs and communities having residential & commercial buildings and EV stations.

Literature review

The short-term scheduling of MGs is one of the interesting and complex concerns for the researchers because planning must consider the interests of all market participants, such as producers, consumers, etc13. However, several researchers have developed MG energy management, considering the producer’s participation. An MG EMS is developed to account for the uncertainty of forecasting energy output from RES and necessary load14,15. A MILP formulation for planning the operation of DC microgrids integrated with solar panels and ES devices was developed in16. A centralized energy management system for MG energy management in the islanded mode is introduced17. In ref.18, a decentralized energy management system for the coordinated operation of MGs in an energy distribution system is developed. The objective is to reduce operating costs in the on-grid- mode while ensuring power stability in the off-grid mode. Authors of19 propose a hybrid energy management system as a hierarchical system for optimizing power transactions, energy storage, and energy distribution in multi-MGs. A two-stage energy management model for active distribution networks is presented in ref.20. In the first stage, the scheduling of MG is performed, and in the second stage, the main grid is planned. In ref.21, the uncertainty in load demand and photovoltaic power forecasts is modelled as a tri-layer MAS22,23 architecture for a day-ahead scheduling strategy. However, in these research works, consumers didn’t have the flexibility to participate directly in the energy market, resulting in restricting consumers from interacting with DER and grid operators.

In this regard, a multi-objective model for home energy management is developed based on the stochastic method to model uncertainties associated with the system24. The authors of ref.25 employed the deep reinforcement learning technique to create an efficient home energy management system. A robust home energy management model is proposed, which takes into consideration all the inherent uncertainties of the system26. However, these works are based on smart home systems that are prosumers; therefore, the individual economic operation of DER and the customer side have not focused. The authors of ref.(s)27,28 present building energy management systems to manage, control and optimization of buildings. In ref.(s)29,30, a dual-layer optimal dispatching model is developed in which the first layer aims to obtain maximum load satisfaction, and the second layer optimizes the power utilization ratio. The majority of these consumer EMSs either do not consider the EVs (or vehicle to grid (V2G) operation),26,31,32 and focus only on residential consumer load.

The rise in the penetration of EVs has motivated the researchers to develop a MG scheduling strategy that also considers EV load along with consumer load33,34,35. However, the modelling of the EV load profile has created further challenges for the development of an adequate MG scheduling strategy. Numerous studies have been conducted to model the EV load profile accurately. It is generally performed using three major techniques: historical data regression method, machine learning prediction model and stochastic simulation method based on probability distribution36. The historical data regression approach37 includes the regression analysis prediction model38 and the day prediction model39. The disadvantages of this strategy include a lack of historical data and conflicting statistical criteria, which can lead to errors in mathematical equations and reduce prediction accuracy. Further, machine learning prediction algorithms have been widely employed in recent years to anticipate short-term load for EV charging. Intelligent algorithms such as neural networks40,41,42,43, support vector machines44,45,46, and deep learning47,48 are frequently utilized. However, the integrity and the accuracy of historical data have a significant impact on forecast results.

The Monte Carlo approach from stochastic simulation method49,50 is currently the most extensively used in MG scheduling to estimate EV load profile (EVLP)51, can simulate random processes and is suitable for macro prediction of unpredictable behaviors of EV users. In this regard, a bi-level optimization strategy for the decentralized coordination of multi-energy communities with EVs and V2G operation has been proposed in which the upper level performs the daily planning of multi-energy communities and in the lower level, the planning of electricity and natural gas networks52. Further, the authors of ref.53,54 have developed a three-layer risk-averse game theoretic-based strategy in which a demand response operation for smart buildings is planned in the first layer, then in the second layer, the scheduling of smart buildings as per demand response program and EV fleets for V2G services is obtained. Finally, the third layer of scheduling for a group of MGs is performed. A multi-stage mechanism for flexibility-oriented energy management of the distribution system is developed, in which the first stage minimizes the operating cost of smart homes that have EVs; the second stage schedules the microgrid, and the third stage takes care of grid flexibility55,56. In these research works, the EVLP is modelled considering the arrival time and SOC of the EV battery. Similarly, more factors could be added to the EVLP model. Like, authors of ref.57proposed an EV charging load prediction model by taking into account numerous random parameters such as place, temperature, and road conditions. Most of these studies assume that (1) As the EV arrives at the station, it starts charging instantaneously irrespective of the available number of EV plug points, (2) the EV will leave the station only after it is fully charged whereas this leaving duration of EV is uncertain and is governed by human behavior. However, these assumptions limit the practical modelling of EVLP.

Research limitations and contributions

Table 1 is provided in order to compare the details of past articles with the presented article. A thorough examination reveals that none of the prior studies assessed the impact of the simultaneous presence of residential & commercial building loads EV operating modes with DRS on the economic aspects of MG. Few studies considered the fair opportunity for the consumers to interact with all the other energy entities of MG directly. Furthermore, it is evaluated that EVLP modelling considering (1) random human behavior in terms of leaving time duration of EV and (2) availability of EV plug-points for the situations where a number of EVs arriving at the stations are more than the available plug-points are not studied. Also, the application of demand response strategy (DRS) to EV load while maintaining their comfort is unexplored.

Thus, this study presents a dual-layer energy management model (DLEM), which aims to achieve the simultaneous optimal operation of DERs and the community layer of the MG. The first layer of DLEM aims to minimize the net-billing cost (NBC) of the community, and the optimal operation of DERs is achieved in the second layer by minimizing the net-operating cost (NOC) of DERs. This will increase the profit of community operator (COR) as well as DER operator. In addition, the impact of various community EV load programs, such as grid to vehicle (G2V) and V2G, with the implementation of EV DRS on other energy units of MG is investigated. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

Development of a distributed model, DLEM which aims to achieve economic and sustainable operation of every energy entity of MG by ensuring their participation in the market and their interactions with each other. The first layer ensures community consumer interaction and minimizes their NBC, and in the second layer, a power scheduling algorithm (PSA) is proposed that optimizes the NOC of DERs and maintains the health of BESS.

-

Advanced probabilistic modelling of EVLP by considering the availability of EV plug-points at EV stations and uncertain events that are totally governed by the EV owner behavior.

-

Introduction of a V2G_DRS mode of EV operation that combines the concept of vehicle-to-grid power transfer services and demand response programs to minimize the peak load of the community while ensuring the EV owner’s comfort.

The remainder of this article is as follows. Section 2 discusses the system description and modelling of model components. Section 3 presents the probabilistic modelling of the electric vehicle load profile (EVLP). Section 4 discusses the modelling of the proposed dual-layer energy management model (DLEM). Section 5 presents the case studies and their results. The article is concluded in Sect. 6.

Model development

This section consists of the modelling of MG components such as solar PV generation systems, energy storage units, load demand and grid connection. Further, a detailed advanced probabilistic modelling of a cluster of EV load, with G2V, V2G and DRS modes, is presented.

System description

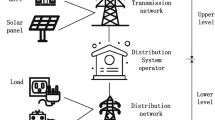

Figure 1 shows the schematic of the system studied in this paper, which consists of MG having a community, DERs, and a main grid. The community consist of residential and commercial buildings and several EV plug-points that facilitate charging and V2G services for EVs, which is connected to an EV aggregator that directly communicates with the COR. The DER layer of MG is comprised of a solar PV generation system and a battery energy storage system (BESS). As per Fig. 1, the COR, DER operator and grid exchange the information with each other and send the control action as per the obtained optimal decision.

Modelling of solar PV power generation system

The electric power generated by the solar PV is calculated as in (1)58.

where, \({P}_{PV}^{R}\) is the rated power of the PV generator, \({G}_{m}^{t}\) is the measured solar radiation at time t, \({G}_{N}\) is the nominal solar radiation which is assumed to be 1000W/m2, \({K}_{\theta }\) is a constant equal to − 0.0357 °C−1, \({\theta }_{A,m}^{t}\) is the measured ambient temperature at time t, \({\theta }_{N}\) is the panel temperature in standard nominal test conditions, which is assumed to be 25 °C and \({\eta }_{PV}\) is the performance coefficient of the PV power converter. \(\mathcal{T}\) is a subset of \({\mathbb{N}}\), represents time intervals, defined as \(\mathcal{T}=\left[\text{1,2},3\dots ,T\right].\) \(T\) is the total number of time intervals.

Modelling of BESS

The BESS is mathematically modelled using (2–3)59.

where \({P}_{B,Ch}^{t}\) and \({P}_{B,Dch}^{t}\) are the charging and discharging power of the BESS at time instant ‘t’, respectively. \({P}_{B,Ch}^{t}\) is always negative and \({P}_{B,Dch}^{t}\) is always positive. \({SOC}_{B}^{t}\) and \({SOC}_{B}^{t+1}\) is the SOC of BESS for the present and next time instant respectively. \({\rho }_{B}\) is the self-discharge rate of the BESS. \({\eta }_{B,Ch}\) and \({\eta }_{B,Dch}\) are the charging and discharging efficiencies of the BESS. \({E}_{B}^{R}\) is the rated energy capacity of BESS.

Moreover, the ESS operation is subject to the following constraints in (4–5).

where \(P_{B,Ch}^{\acute{M}}\) and \(P_{B,Dch}^{\acute{M}}\) are the maximum charging and discharging limit of the BESS. The SOC of the BESS \({(SOC}_{B}^{t})\) should remain in the limits which are minimum (\(SoC_{B}^{\acute{m}} )\) and maximum \((SoC_{B}^{\acute{M}} )\).

Load modelling of building

The load demand of each building can be represented using (6).

where \({P}_{L}^{t,bg}\) is the predicted total load of the building ‘bg’ at time interval ‘t’. \(P_{L}^{\acute{m}}\) and \(P_{L}^{\acute{M}}\) are the minimum and maximum limits of the load, respectively. \({\mathcal{N}}_{BG}\) is a subset of \({\mathbb{N}}\), represents number of buildings intervals, defined as \({\mathcal{N}}_{BG}=\left[\text{1,2},3\dots ,{N}_{BG}\right].\) \({N}_{BG}\) is the total number of buildings.

Grid connection modelling

The grid can export power to COR and can import power from DERs and is represented by (7).

where \({P}_{G,Ex}^{t}\) is the power exported to the COR by the grid and \({P}_{G,Im}^{t}\) is the power imported by the grid from the DERs.

Proposed advanced probabilistic modelling of EVLP

This section details the advanced probabilistic modelling of EVLP for clusters of various types of EVs. In this study, the EVLP is obtained for two user modes, i.e., G2V, where only charging of EVs is taken into account and V2G_DRS, which facilitates both charging & discharging of EVs and application of DRS to the EVs. The daily distance traveled by an EV and the arrival time (the time at which EV arrives at the EV station) are extracted by using Monte Carlo simulation from the log-normal and normal probability density functions, respectively. This work takes into account the two most essential conditions in the probabilistic modelling of EVLP, which are as follows:

-

If the number of available EV plug-points is less than the number of EVs arriving at the station, in that case the arrival time of the EV and the plug-in time (time at which EV is plugged-in) may not be equal.

-

The expected time duration at which EV may leave the EV station, i.e., leave time duration, is highly uncertain and is governed by human behaviour. Therefore, it may not be equal to the estimated plug-out time (the time at which EV is fully charged).

Hence, in order to model the EVLP accurately, the above conditions are important. As the leave time duration of the EV and the type of EV that is input by the EV owners are uncertain parameters, they are modelled as a random variable.

This study considers four different types of EVs. The EV owners are segregated into three categories: employees of the buildings, visitors coming to the buildings, and residential public coming to charge their EVs.

Let the total number of EVs coming to the station be \({N}_{EV}\). Further, the number of EVs of employees (\({N}_{EV}^{E}\)), visitors (\({N}_{EV}^{V}\)), and residential people (\({N}_{EV}^{R}\)) can be calculated using (8–11).

where \({\alpha }_{E}\), \({\alpha }_{V}\) and \({\alpha }_{R}\) are the ratios of employees, visitors, and residential EV owners with respect to total number of EVs.

The mean and standard deviation used to generate the arrival time of EV ( \({T}_{AT}^{n})\) for employees, visitors, and residential EV owners are shown in Table 2.

Grid to vehicle mode (G2V)

This mode focuses on unidirectional power flow, i.e., only charging the EVs. As the EV reaches the station, the EV aggregator takes the specific input from the EV owner, such as the present SOC of the EV and the leave time, i.e., the expected time at which the EV may leave the station, irrespective of its SOC. Using these inputs, the EV aggregator will calculate the estimated plug-out time (when the EV will be fully charged) and display it to the EV owner. If the leave time is less than the estimated plug-out time, then a notification will be sent to the EV owner regarding this difference in this time, and depending on the owner’s input, represented by \({\xi }_{G2V}^{n}\), aggregator takes the decision.

The plug-in time of EV \(({T}_{PI}^{n})\) can be calculated using (12). It is assumed that the plug-in time of the EV is the start time of charging of EV.

where \({T}_{PO}^{n-1}\) is the plug-out time of previous EV. \({N}_{EV\_P}\) is the number of EV plug-points. \({\mathcal{N}}_{EV}\) is a subset of \({\mathbb{N}}\), represents number of EVs and is defined as \({\mathcal{N}}_{EV} = \left[ {1,2,3, \ldots ,N_{EV} } \right].\) \(N_{EV}\) represents the total number of EVs.

The charging duration \(({TD}_{Ch}^{n})\) of each EV can be obtained from (13)60.

where \({SOC}_{EV,PI}^{n,d}\) is the SOC of \(n{\text{th}}\) EV having \(d{\text{th}}\) type, at the time of plug-in; \({E}_{EV}^{R,d}\) represents the rated energy capacity of EV in kWh, \({P}_{EV,Ch}^{d}\) is the rated charging rate of EV in kW/h; \({\eta }_{EV,Ch}\) is the charging efficiency of EVs. \({\mathcal{D}}_{EV}\) is a subset of \({\mathbb{N}}\), represents type of EV and is defined as \({\mathcal{D}}_{EV} = \left[ {1,2,3 \ldots ,D_{EV} } \right].\) \(D_{EV}\) represents the total types of EVs. \(N_{EV}\) and \(D_{EV}\) represents the total number and total types of EVs, respectively.

The estimated plug-out time of EV \(({T}_{EPO}^{n})\) can be further calculated using (14).

The actual plug-out of EV \({(T}_{PO}^{n})\) totally depends on the leave time duration of EV \({(TD}_{L}^{n})\) and the decision input \(({\xi }_{G2V}^{n})\) given by the EV owner and can be calculated by (15).

The charging power \({(P}_{Ch}^{t,n })\) required to charge the EV can be estimated using (16). The associated time interval to this charging power can be calculated using (12) and (15)60.

As EV charging time intervals are independent of each other, therefore they can be accumulated. The daily EVLP of a large number of EVs for G2V mode can be calculated using (17).

where \({P}_{EV,G2V}^{t}\) is the daily EVLP of \({(N}_{EV})\) EVs in case of G2V user mode.

Vehicle to grid and demand response strategy mode (V2G_DRS)

This mode is a combination of V2G and governed grid to vehicle, i.e., the DRS mode of EVs. It provides flexibility to the EV owner of discharging their EV batteries and earning financial incentives from it. The V2G deals with the bi-directional power flow between the EVs, and MG and the DRS govern the G2V operation. In the V2G_DRS mode, the EV aggregator plays two vital roles. It allows the EVs to discharge during dynamic peak price hours and charge them during low price hours. The amount of power to be discharged from the EVs is dynamic and depends on the SOC and leave time duration of the EV. Hence, the EV aggregator calculates it and makes sure that the EV is fully charged (after participating in V2G) before the EV leaves the station. This maintains the comfort of EV owners and motivates them to contribute to V2G. Further, it also encourages the EV owners to participate in the DRS by shifting their charging load from peak load hour to off-peak load hour.

The plug-in time of EV \(({T}_{PI}^{n})\) and the charging duration \(({TD}_{Ch}^{n})\) of each EV can be obtained from (12) and (13), respectively.

The desired plug-out time of EV \(({T}_{DPO}^{n})\) can be calculated using (18).

The EV aggregator takes the decision \(({K}_{V2G\_DRS}^{n})\) of performing V2G/DRS/G2V depending on the following conditions, as shown by (19).

where \(T_{PP}^{start}\) and \(T_{PP}^{end}\) are the start and end of the peak price time interval. \(TD_{ L}^{\acute{m}}\) is the minimum value of leave time duration of EV required for the V2G.

Decision of the EV aggregator: allowing the EV owner to perform V2G

The plug-in time of EV is assumed to be the start of the discharging time of the EV. The maximum discharging duration \((TD_{Dch}^{\acute{M},n} )\) of EV until it reaches the threshold SOC (set by the EV aggregator) can be calculated from (20)61.

where \(SOC_{EV}^{\acute{M}}\) refers to a maximum limit of SOC of an EV battery and \({SOC}_{EV,Dch}^{th}\) refers to threshold limit of SOC of EV battery till which discharging can be performed. \({P}_{EV,Dch}^{d}\) is the rated discharging rate of EVs in kW/h. \({S}_{EV}^{n,d}\) is the distance travelled by the EV and \(S_{EV}^{\acute{M},d}\) is the maximum distance EV can travel in one charge in km.

The estimated plug-out time of EV \(({T}_{EPO}^{n})\) where EV starts charging after the end of peak price \({(T}_{PP}^{end})\) can be calculated using (21).

Using above equations, the discharging duration \({(TD}_{Dch}^{ n})\) of EV can be obtained using (22).

The time at which discharging of EV ends (\({T}_{Dch,end}^{n})\) can be calculated using the (23).

The discharging power \({(P}_{Dch}^{t,n})\) taken from the EV can be estimated using (24). The associated time interval to this discharging power can be calculated using (12) and (23)61.

The time at which charging of EV starts \(({T}_{Ch, starts}^{ n})\) after discharging is calculated from (25).

The actual plug-out time of EV \(({T}_{PO}^{n})\) which will be the time at which discharging and charging process of EV will end can be estimated by (26).

The charging power of EV can be estimated using (16). As EVs discharging and charging time intervals are independent of each other, therefore they can be accumulated.

By combining all the cases above, the daily EVLP of a large number of EVs for V2G operation can be calculated using (27).

where \({P}_{EV,V2G}^{t}\) is the daily EVLP of \({(N}_{EV})\) EVs in case of V2G user operation.

Decision of the EV aggregator: Sending the request to the EV owner to participate in DRS

In this case also the plug-in time of EV \(({T}_{PI}^{n})\) and the charging duration \(({T}_{Ch}^{n})\) of each EV can be obtained from (12) and (13), respectively. Further, depending on the EV owner’s input \({(\xi }_{DRS}^{ev})\) towards the sent DRS request, the EV aggregator takes the decision. The actual plug-out time of EV \(({T}_{PO}^{n})\) can be calculated using (28).

Moreover, the charging power calculation of EV is similar as in (16). The daily EVLP for a DRS operation of a large number of EVs can be calculated using (29).

The total EV load for V2G_DRS \((P_{EV,V2G\_DRS}^{t} )\) can be defined as in (30).

Modelling of proposed dual layer energy management model (DLEM)

This section details the modelling of the DLEM developed in the presented work. It ensures individual participation and interactions between the community, DERs, and grid in order to achieve energy management of MG. In the first stage, community energy management is performed by the community operator (COR), and the power schedule is obtained by minimizing the NBC of the COR. This power schedule consists of time slots in a day of grid and DERs to fulfil the demand of the community. Then, in the second layer, the DER operator performs the energy management of the DERs while fulfilling the demand request sent by the COR. It minimizes the NOC of DERs through a PSA that optimally utilizes the BESS to maintain its health. Further, the final schedule is sent to the grid to fulfil the demand as per the first and second layers. The implementation steps of the proposed DLEM are presented in Fig. 2. It should be remarked that the uncertainties caused by the RERs, load demand, and EVLP are included in the model through the scenario generation and reduction technique.

First layer of DLEM

This stage is associated with the COR and aims to minimize the electricity and EV charging bills of the building and EV owners. The subcomponents of the first layer are discussed in the following sub-sections.

Objective function

The total load of the community \({(P}_{TCL}^{t})\) can be expressed as (31). The objective function of this stage is shown in (32) and is minimized under the constraint described in (33)-(34).

where \({P}_{TCL,DER}^{t,}\) is the load demand of the community met by the DER layer at time ‘t’ in kW and \({P}_{G,Ex}^{t}\) is the power exported by the grid to meet the demand of the community in kW. \({\lambda }_{DER}^{t}\) and \({\lambda }_{G}^{t}\) are the rate of energy of DERs and grid in $/kWh. \(P_{{G,{ }Ex}}^{\acute{M}}\) is the maximum limit of power exported by the grid.

Second layer of DLEM

The second layer of DLEM is associated with the DER operator and focuses on the minimization of the NOC of DERs. It takes the input from the first layer and uses a proposed PSA to obtain the power schedule. The components of the second layer are discussed in the following sub-sections.

Objective Function

In this stage, the NOC of DERs is minimized, and the objective function consists of the O&M cost of the solar PV system, BESS, the cost associated with the power imported by the grid and the cost earned by the DER operator for supplying power to the buildings and EVs getting charged at EV charging stations. The objective function NOC of DERs becomes as shown in (35).

where, \(\zeta_{PV}^{O\& M}\) is the operation and maintenance coefficient for the installed PV system in $/h. \({P}_{B,Ch/Dch}^{t}\) is BESS’s charging or discharging power at time instant ‘t’. \({\Phi }_{B}^{O\&M}\) and \({\Psi }_{B}^{O\&M}\) are the variable and fixed O&M cost coefficients of BESS in $/kWh and $/h, respectively, where \({\Phi }_{B}^{O\&M}\) depends on the \({P}_{B,Ch/Dch}^{t}\).

The formulated cost objective function is minimized subject to the constraints presented in (4–6), (36–37):

where \({P}_{TCL,DER}^{t}\) , \({P}_{PV}^{t}\) and \({P}_{G,Im}^{t}\) is the total community load demand fulfilled by the DERs, power generated by solar PV, and power imported by the grid from MG at time instant ‘t’. \({P}_{B,Ch/Dch}^{t}\) is positive when BESS discharges, and it is negative when BESS is charging. \(P_{{G,{ }Im}}^{\acute{M}}\) is the maximum limit of power imported by the grid.

Power scheduling algorithm (PSA)

In order to achieve the optimal operation of DERs, especially BESS, the PSA is proposed in the second layer of DLEM. It decides the operation of DERs based on several factors, such as solar PV power, load demand power, and the SOC condition of the BESS. In PSA, the decision for every time instant ‘t’ is taken based on the equivalent power at a time ‘t’ \(({P}_{EP}^{t})\) calculated using (38), average grid price \({(\lambda }_{G}^{avg})\), the threshold value of SOC \({(SOC}_{B, th}),\) grid price \({(\lambda }_{G}^{t})\) and SOC of BESS \(({SOC}_{B}^{t})\) at a time ‘t’. The \({SOC}_{B, th}\) is the minimum value of SOC of BESS required to maintain the optimum depth of discharge (DOD). If the \({P}_{EP}^{t}\) is negative, the charging of BESS and power to be exported to the grid is dependent on the average and present grid price of energy. Whereas for the positive value of \({P}_{EP}^{t}\), the decision of discharging of BESS and sending the demand request to the grid is taken based on the SOC condition of BESS. In this way, the DER operator can sell the extra solar PV energy units at the time of higher grid prices and can maximize the profit, whereas by using the SOC condition for discharging of BESS, the health of BESS can be maintained.

Case study and simulation results

This section discusses a case study with simulation results. The developed mathematical formulation was coded under MATLAB R2020a, and the optimization problems were solved using a well-known meta-heuristic algorithm, particle swarm optimization61. All the simulations were run on an Intel® Core™ i7-1065G7, 1.50 GHz, 16.00 GB RAM, over a 24-h horizon. The time step is fixed equal to 1 hour.

Initializing

This section discusses the case studies and the input data taken into account. In this study, the ratings of the model components are obtained from the MG setup installed at the university campus. Therefore, the rated capacity of the solar PV system and BESS of MG is 41kWp and 81kWh (360 V, 225Ah), respectively.

Further, as the obtained data has a large number of sets, the scenario reduction technique is used to reduce them into 10 scenarios. Figure 3 shows the solar PV generation and load demand data of residential and commercial buildings obtained from the university campus where the MG setup is installed. Further, Fig. 4 shows the reduced 10 scenarios of solar PV generation and load demand data of residential building and commercial buildings I & II, respectively. Table 3 shows the different simulation parameters used in the study. Moreover, the details of the types of EVs, along with their specifications, are discussed in Table 4.

Figure 5 shows the daily profile of solar PV power, total load of buildings and load of residential and commercial buildings I & II, which is used as an input for all the cases. Further, Fig. 6 shows the per unit cost of energy exchange with the grid.

Results of probabilistic modelling of EV load profile (EVLP)

This section details the results obtained from modelled EVLP under G2V and V2G_DRS mode of operation of EV. The probabilistic modelling of EVLP under G2V operation gives the charging profile of EV, and V2G_DRS mode models the charging/discharging load profile of EV. In this study, the EVLP modelling is performed for 10, 20, and 30 EVs, and for each level, 400 EV load scenarios are generated using the developed probabilistic model. These scenarios were further reduced to 10 scenarios using the scenario reduction technique. The EV load scenarios generated for G2V and V2G_DRS operation mode considering 20 EVs are shown in Fig. 7a and 7b, respectively. Moreover, Fig. 8 shows the modelled EVLP for G2V and V2G_DRS operation modes considering 10,20 and 30 EVs.

Results obtained from DLEM without considering EV penetration

This section shows the results obtained from the first and second layers of DLEM without considering EV penetration. The power imported by COR from DERs and grid is represented by P_COR_DER and P_COR_GR, respectively. The power exported to the grid from DERs is represented by P_DER_GR.

First layer

Figure 9 shows the expected time slots in a day of grid and DERs provided by COR to fulfil its demand. As it depends on the energy exchange prices of the grid and DERs, it is valid for all the cases.

Second layer

Figure 10 shows the hourly schedule of total load demand of COR, solar PV generation, BESS power, P_COR_DER, P_COR_GR and P_ DER_GR.

It is observed from Fig. 10 that from time instants, 1st to 8th, the load of COR is fulfilled by the grid and after that till 17th it is fulfilled by DERs. Further, for time instants, 18th and 19th the load is fulfilled by both DERs and grid. After that, the load is fulfilled only by grid till 24th time interval. Moreover, as the proposed PSA optimizes the operation of BESS, therefore, the BESS is only discharged during peak price hours of the grid.

Comparative study of proposed DLEM with existing energy management models

The performance of DLEM is compared to two types of existing energy management models. Among them, the first model considers interactions of COR only to the DER layer20,22,52, whereas the second model involves interactions of COR only to the grid31, represented by EEM 1 and EEM 2, respectively. Table 5 shows the results in terms of NBC of community and NOC of DERs with these existing models and proposed DLEM. The negative value of NOC shows the profit earned by the DER layer operator. Further, Table 6 shows the effect of DLEM on NBC of the community layer and profit of DER layer with respect to existing energy management models.

It is clearly observed from Tables 5 and 6 that DLEM provides the minimum NBC for COR and maximum profit to DER operators. It has decreased the NBC of COR by 12.99% and 16.29% with respect to EEM 1 and EEM 2, respectively. Further, DLEM increases the economic profit of DER operators by a 16.96% increase. It is evident from these results that DLEM is a more effective and profitable energy management model than previously reported models.

Performance analysis of DLEM considering EV penetration

Further, the performance of DLEM with EV penetration is analyzed based on power exchanged between COR, DERs and GR. The effect of proposed modes of EVs, i.e.., G2V and V2G_DRS on these power exchanges is evaluated. Also, the impact of the increasing number of EVs on these power exchanges is examined by considering 10, 20 and 30 EVs.

Effect of EV and its mode of operation on various parameters

Figure 11 shows the schedule of power exchange between COR, DERs, and grid with 30 EVs in G2V and V2G_DRS modes of EV operation.

It is observed from Fig. 11 that as EV penetration occurs in the system, the P_COR_DER and P_COR_GR significantly increase independent of the mode of EV operation. In contrast, the P_COR_GR is dependent on the mode of EV operation. Due to this, the P_COR_GR becomes the minimum for the V2G_DRS case. It is mainly because this mode focuses on discharging of EVs/shifting the EV load during/ from peak hour time as per the grid, which reduces the demand request of COR on the grid. The P_ DER_GR is highest for without EV case, and it drastically reduces after EV penetration, as shown for G2V case. However, with V2G_DRS, it is further increased. Therefore, it can be concluded that V2G_DRS mode benefits all the energy entities of MG, i.e., community, DERs, and grid.

Effect of increasing number of EVs

Figure 12a and 12b shows the schedule of power exchanged between COR, DERs and grid with 10, 20, 30 EVs under G2V and V2G_DRS mode of EV operation, respectively.

It is evident from the Fig. 12a and 12b, as the number of EVs increases in the system, the P_COR_DER and P_COR_GR also increase. Whereas P_DER_GR decreases with the increase in EVs for the G2V case, in comparison, it almost remains constant for V2G_DRS mode. It signifies that the increasing number of EVs has no considerable effect on P_DER_GR.

Cumulative results obtained from DLEM for all the cases

This section discusses the summary of all the cases considered regarding energy exchanged in a day between COR, DERs, and grid, as well as NBC of COR and NOC of DERs. Table 7 shows the information of the cases studied.

Figures 13, 14 and 15 show the total energy imported by COR from DERs, total energy imported by COR from the grid and total energy exported by DERs to the grid obtained by DLEM for all the case studies, respectively.

It can be observed from Figs. 13 and 14 that the energy imported by COR from DERs and grid keeps on increasing as the number of EVs increases, irrespective of the mode of EV operation. However, the energy imported by COR from DERs remains similar in both modes of EV operation. Whereas the energy imported by COR from the grid is maximum with G2V case and is lowest with the V2G_DRS mode of operation.

From Fig. 15 it can be noted that the total energy exported by the DERs to the grid is maximum for without EV case, and it starts decreasing as the number of EVs increases irrespective of the mode of EV operation. This is mainly because after the EV penetration, the total load of the community increases, and DERs export more power to the community than the grid. However, there is a slight increment in total power exported by the DERs to the grid with V2G_DRS mode.

Figures 16 and 17 show the NBC of COR and the NOC of DERs for all the cases, respectively.

From Fig. 16, it can be observed that the NBC of COR is lowest for without EV case and highest with the G2V mode. Moreover, the V2G_DRS mode decreases the NBC of COR irrespective of the number of EVs. Further, in Fig. 17, the negative values of DERs’ NOC show the profit earned by DER operator. It is noticed from Fig. 17 that the profit earned by DERs is maximum for, without EV cases but starts decreasing as the EV penetration increases.

The V2G_DRS mode of EV operation has a significant impact on the total energy imported by COR from the grid, total energy exported by DERs to grid and NBC of COR. Therefore, Table 8 shows the percentage increment/decrement in these parameters obtained from the V2G_DRS mode of EV operation with respect to G2V for different numbers of EVs.

From Table 8 it is observed that, for 10, 20 and 30 no. of EVs, the V2G_DRS mode of EV operation has decreased the total energy imported by COR from the grid by 7.14%, 9.77% & 11.39%, respectively. Further, it has increased the total energy exported by DERs to the grid by 0.6%, 0.84% and 2.51% for the same no. of EVs, respectively. This change in these parameters significantly impacts the operation of COR and thus decreases the NBC of COR by 3.01%, 6.02% & 7.88% for 10,20 & 30 EVs, respectively. Also, this change is magnified by the increase in the number of EVs; therefore, it is highest for 30 EVs. Consequently, it can be concluded that the V2G_DRS mode of EV operation helps optimize the NBC of COR and the operation of DERs by increasing its export.

Conclusion

A dual-layer energy management (DLEM) model is developed for the optimal operation of a microgrid (MG) consisting of a community, DERs and a grid. The community is comprised of residential and commercial buildings with electric vehicle (EV) chargers. The DER layer of MG is composed of solar PV and a battery energy storage system (BESS). The proposed DLEM aims to achieve economic and sustainable operation of every energy entity of MG and ensures their interaction with each other. The first layer of DLEM focuses on minimizing the net-billing cost (NBC) of the community operator (COR), whereas the second layer minimizes the net-operating cost (NOC) and maximizes the profit earned by the DER operator. The COR generates the demand request in the first layer of DLEM and sends it to DER and the grid. Further, in the second layer of DLEM, the optimal schedule of DERs is obtained using a formulated power scheduling algorithm (PSA) and takes into account the demand request of COR. The PSA makes the decision to charge/discharge BESS, export power to the grid, and send information for exporting power to COR by the grid in case of insufficient power.

Moreover, an advanced probabilistic electric vehicle load profile (EVLP) model is developed by considering (1) the availability of EV stations and (2) uncertain human behaviour in terms of the random time at which the EV may leave the station. The EVLP is modelled for two operating modes, i.e., grid to vehicle (G2V) and a novel vehicle to grid with EV demand response strategy (V2G_DRS) mode. The V2G_DRS mode motivates the EV owners to participate in peak load management by either performing vehicle-to-grid transfer or shifting the EV load from peak load hours to off-peak load hours as a demand response act.

The data for solar PV and load demand are obtained from the MG setup installed at the university campus. However, a scenario reduction technique is used to deal with the uncertainties of the obtained data. Further, to evaluate the performance of DLEM, various scenarios were considered, and the highlights of the results are as follows:

-

(1)

Simulation results reveal that the DLEM decreased the billing cost of COR by 13% and increased the profit of the DER operator by 17% compared to existing energy management models.

-

(2)

The efficacy of DLEM is evaluated by considering three EV penetration levels, i.e., 10, 20, and 30 EVs, with each mode of EV operation. The results conclude that, after the penetration of EVs, the total energy imported by COR from DERs and the grid is increased, and the energy exported by the DERs to the grid is decreased, irrespective of EV mode.

-

(3)

The V2G_DRS mode of EV operation has decreased the energy import by COR from the grid by 7.14%, 9.77% and 11.39% for 10, 20 and 30 EVs, respectively, as compared to the G2V mode. Moreover, the billing cost of COR has decreased by 3.01%, 6.02% & 7.88% for the same number of EVs, respectively.

Thus, the proposed DLEM with V2G_DRS mode results in the individual economic operation of all the energy layers of MG, especially the community and DER layers, making them more sustainable. For future research direction, the impact of flexible thermostatically controllable loads can be analyzed to provide a more cost-effective energy management solution for consumer entity of MGs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- MG:

-

Microgrid

- IEA:

-

International Energy Agency

- COP:

-

Conference of Parties

- RER:

-

Renewable energy resource

- DER:

-

Distributed energy resource

- EV:

-

Electric vehicles

- COR:

-

Community operator

- BESS:

-

Battery energy storage system

- DLEM:

-

Dual-layer energy management

- NOC:

-

Net-operating cost

- PSA:

-

Power scheduling algorithm

- DRS:

-

Demand response strategy

- EVLP:

-

Electric vehicle load profile

- G2V:

-

Grid to vehicle

- V2G:

-

Vehicle to grid

- SOC:

-

State of charge

- NBC:

-

Net-billing cost

- \(t \in {\mathcal{T}}\) :

-

Time interval, \({\mathcal{T}} \subseteq {\mathbb{N}}, {\mathcal{T}} = \left\{ { 1,2,3, \ldots ,T} \right\}\)

- \(bg \in {\mathcal{N}}_{BG}\) :

-

Number of buildings,\({\mathcal{N}}_{BG} \subseteq {\mathbb{N}}, {\mathcal{N}}_{BG} = \left\{ { 1,2,3, \ldots ,N_{BG} } \right\}\)

- \(n \in {\mathcal{N}}_{EV}\) :

-

Number of EVs,\({\mathcal{N}}_{EV} \subseteq {\mathbb{N}}, {\mathcal{N}}_{EV} = \left\{ { 1,2,3, \ldots ,N_{EV} } \right\}\)

- \(d \in {\mathcal{D}}_{EV}\) :

-

Type of EVs, \({\mathcal{D}}_{EV} \subseteq {\mathbb{N}}, {\mathcal{D}}_{EV} = \left\{ { 1,2,3, \ldots ,D_{EV} } \right\}\)

- \(P_{PV}^{R}\) :

-

Rated power of the solar PV generator in kW

- \(\eta_{PV}\) :

-

Performance coefficient of the PV power converter

- \(P_{L}^{\acute{m}}\) and \(P_{L}^{\acute{M}}\) :

-

Minimum and maximum limits of load demand in kW

- \(\eta_{PV}\) :

-

Efficiency of solar PV system

- \(G_{m}^{t}\) :

-

Measured solar radiation at time ‘t’

- \(G_{N}\) :

-

Nominal solar radiation in W/m2

- \(\theta_{A,m}^{t}\) :

-

Measured ambient temperature at time ‘t’

- \(\theta_{N}\) :

-

Panel temperature in standard test conditions at °C

- \(K_{\theta }\) :

-

Temperature coefficient in °C−1

- \(\zeta_{PV}^{O\& M}\) :

-

Operation and maintenance coefficient for the installed PV system

- \(\lambda_{G}^{avg}\) :

-

Average value of energy trading price of the grid in $/kWh

- \(\rho_{B}\) :

-

Self-discharge rate of BESS

- \(\eta_{B,Ch/DCh}\) :

-

Charging and Discharging efficiency of BESS

- \(E_{B}^{R}\) :

-

Rated energy capacity of BESS.

- \(P_{B,Ch/Dch}^{\acute{M}}\) :

-

Maximum limit of charging and discharging power of BESS

- \(SOC_{B}^{\acute{m}}\) and \(SOC_{B}^{\acute{M}}\) :

-

Minimum and Maximum limits of the SOC of the BESS

- \(SOC_{B, th}\) :

-

Threshold value of SOC of the BESS

- \(P_{B,Ch}^{\acute{M}}\) and \(P_{B,Dch}^{\acute{M}}\) :

-

Maximum charging and discharging limit of the BESS

- \(\Phi_{B}^{O\& M}\) and \(\Psi_{B}^{O\& M}\) :

-

Variable and fixed O&M cost coefficients of BESS

- \(\eta_{EV,Ch} /\eta_{EV,Dch}\) :

-

Charging and Discharging efficiency of EV

- \(E_{EV}^{R,d}\) :

-

Rated capacity of dth type EV battery

- \(SOC_{EV}^{\acute{M}}\) :

-

Maximum value of SOC of EV battery

- \(SOC_{EV,Dch}^{th}\) :

-

Threshold limit of SOC of EV battery till which discharging can be performed

- \(P_{EV,Ch/Dch}^{d}\) :

-

Rated charing/ discharging rate of EV in kW/h

- \(N_{EV\_P}\) :

-

Number of EV plug-points at EVS

- \(N_{EV}^{E}\), \(N_{EV}^{R}\) , \(N_{EV}^{V}\) :

-

Number of EVs of employees, residential people and visitors

- \(\alpha_{E}\), \(\alpha_{V}\) and \(\alpha_{R}\) :

-

Ratios of employees, visitors, and residential EV owners.

- \(S_{EV}^{\acute{M},d}\) :

-

Maximum distance EV can travel in one charge

- \(TD_{{{ }L}}^{\acute{m}}\) :

-

Minimum value of leave time duration required for V2G operation

- \(P_{L}^{t,bg}\) :

-

Load demand of the building in kW at time ‘t’

- \(P_{TCL}^{t}\) :

-

Total load demand of the community in kW

- \(P_{TCL,DER}^{t}\) :

-

Load demand of the community fulfilled by DERs in kW at time ‘t’

- \(P_{PV}^{t}\) :

-

Power generated by solar PV in kW at time ‘t’

- \(P_{B,Ch}^{t} /P_{B,Dch}^{t}\) :

-

Charging and discharging power of the BESS at time instant ‘t’

- \(P_{G,Ex}^{t}\) :

-

Power exported by the grid to COR in kW at time ‘t’

- \(P_{G,Im}^{t}\) :

-

Power imported by the grid from DERs in kW at time ‘t’

- \(SOC_{B}^{t}\) and \(SOC_{B}^{t + 1}\) :

-

SOC of BESS at ‘t’ and ‘t + 1’ instant

- \({\mathbb{C}}_{COR}^{t}\) :

-

Net-billing cost of COR in $

- \({\mathbb{C}}_{DER}^{t}\) :

-

Net-operating cost of DER operator in $

- \(\lambda_{G}^{t}\) :

-

Energy trading price of the grid at a time ‘t’ in $/kWh

- \(\lambda_{DER}^{t}\) :

-

Energy trading price of the DERs at a time ‘t’ in $/kWh

- \(P_{EP}^{t}\) :

-

Equivalent power in kW at time ‘t’

- \(T_{PI}^{n}\) :

-

Plug-in time of EV

- \(T_{AT}^{n}\) :

-

Arrival time of EV

- \(T_{PO}^{n}\) :

-

Actual plug-out time of EV

- \(TD_{Ch}^{n}\) :

-

Time duration required by the EV for getting fully charged

- \(TD_{Dch}^{\acute{M},n}\) :

-

Maximum discharging time duration of EV

- \(TD_{Dch}^{ n}\) :

-

Actual discharging duration of EV

- \(T_{EPO}^{n}\) :

-

Estimated plug-out time of EV

- \(T_{DPO}^{n}\) :

-

Desired plug-out time of EV

- \(S_{EV}^{n,d}\) :

-

Distance travelled by nth EV of dth type

- \(TD_{{{ }L}}^{n}\) :

-

Leave time duration of nth EV

- \(\xi_{G2V}^{n}\) :

-

EV owner’s input regarding G2V operation

- \(\xi_{DRS}^{n}\) :

-

EV owner’s input regarding participation in DRS operation

- \(K_{{{\text{V}}2{\text{G}}\_{\text{DRS }}}}^{n}\) :

-

Decision variable of EV aggregator

- \(T_{Dch,end}^{n}\) :

-

Time at which discharging of EV ends

- \(T_{Ch, starts}^{ n}\) :

-

Time at which charging starts after discharging process of EV

- \(SOC_{EV,PI}^{n,d}\) :

-

SOC of EV at the time of plug-in

- \(P_{EV,G2V}^{t}\), \(P_{EV, V2G}^{t}\), and \(P_{EV,DR}^{t}\) :

-

Daily EVLP of \(N_{EV}\) EVs in case of G2V, V2G and DR operation

References

Conference of Parties (COP26). United Nations https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop26#:~:text=The%20UN%20Climate%20Change (2021).

International Energy Agency. Net Zero by 2050: A roadmap for the global energy sector. 70 (2021).

Erenoğlu, A. K., Şengör, İ, Erdinç, O., Taşcıkaraoğlu, A. & Catalão, J. P. S. Optimal energy management system for microgrids considering energy storage, demand response and renewable power generation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 136, 107714 (2022).

Ahmed, I. et al. Review on microgrids design and monitoring approaches for sustainable green energy networks. Sci. Rep. 13, 21663 (2023).

Sharma, P., Bhattacharjee, D., Mathur, H. D., Mishra, P. & Siguerdidjane, H. Novel optimal energy management with demand response for a real-time community microgrid. In Proc. - 2023 IEEE Int. Conf. Environ. Electr. Eng. 2023 IEEE Ind. Commer. Power Syst. Eur. EEEIC / I CPS Eur. 2023 1–6 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1109/EEEIC/ICPSEurope57605.2023.10194855.

Eseye, A. T., Zheng, D., Li, H. & Zhang, J. Grid-price dependent optimal energy storage management strategy for grid-connected industrial microgrids. In IEEE Green Technol. Conf. 124–131 (2017) https://doi.org/10.1109/GreenTech.2017.24.

Tong, Z., Mansouri, S. A., Huang, S., Rezaee Jordehi, A. & Tostado-Véliz, M. The role of smart communities integrated with renewable energy resources, smart homes and electric vehicles in providing ancillary services: A tri-stage optimization mechanism. Appl. Energy 351, 121897 (2023).

Xing, X. & Jia, L. Energy management in microgrid and multi-microgrid. IET Renew. Power Gener. 00, 1–29 (2023).

Farinis, G. Κ & Kanellos, F. D. Integrated energy management system for microgrids of building prosumers. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 198, 107357 (2021).

Wang, H., Yao, H., Zhou, J. & Guo, Q. Optimized scheduling study of user side energy storage in cloud energy storage model. Sci. Rep. 13, 18872 (2023).

Ding, Y. et al. A comprehensive scheduling model for electric vehicles in office buildings considering the uncertainty of charging load. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 151, 109154 (2023).

Sheidaei, F. & Ahmarinejad, A. Multi-stage stochastic framework for energy management of virtual power plants considering electric vehicles and demand response programs. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 120, 106047 (2020).

Sharma, P., Dutt Mathur, H., Mishra, P. & Bansal, R. C. A critical and comparative review of energy management strategies for microgrids. Appl. Energy 327, 120028 (2022).

Xiang, Y., Liu, J. & Liu, Y. Robust energy management of microgrid with uncertain renewable generation and load. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 7, 1034–1043 (2016).

Jiang, Q., Xue, M. & Geng, G. Energy management of microgrid in grid-connected and stand-alone modes. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 28, 3380–3389 (2013).

Ghadimi, N., Nojavan, S., Abedinia, O. & Dehkordi, A. B. Chapter 2 - Deterministic-based energy management of DC microgrids. In Risk-based Energy Management (eds Nojavan, S. et al.) 11–30 (Academic Press, 2020).

Olivares, D. E., Cañizares, C. A. & Kazerani, M. A centralized energy management system for isolated microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 5, 1864–1875 (2014).

Wang, Z., Chen, B., Wang, J. & Kim, J. Decentralized energy management system for networked microgrids in grid-connected and islanded modes. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 7, 1097–1105 (2016).

Wang, Y., Mao, S. & Nelms, R. M. On hierarchical power scheduling for the macrogrid and cooperative microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 11, 1574–1584 (2015).

Javanmard, B., Tabrizian, M., Ansarian, M. & Ahmarinejad, A. Energy management of multi-microgrids based on game theory approach in the presence of demand response programs, energy storage systems and renewable energy resources. J. Energy Storage 42, 102971 (2021).

Sheidaei, F., Ahmarinejad, A., Tabrizian, M. & Babaei, M. A stochastic multi-objective optimization framework for distribution feeder reconfiguration in the presence of renewable energy sources and energy storages. J. Energy Storage 40, 102775 (2021).

Mansouri, S. A. et al. A sustainable framework for multi-microgrids energy management in automated distribution network by considering smart homes and high penetration of renewable energy resources. Energy 245, 123228 (2022).

Li, Y. & Li, K. Incorporating demand response of electric vehicles in scheduling of isolated microgrids with renewables using a bi-level programming approach. IEEE Access 7, 116256–116266 (2019).

Tostado-Véliz, M., Gurung, S. & Jurado, F. Efficient solution of many-objective home energy management systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 136, 107666 (2022).

Alam, M. M., Rahman, M. H., Ahmed, M. F., Chowdhury, M. Z. & Jang, Y. M. Deep learning based optimal energy management for photovoltaic and battery energy storage integrated home micro-grid system. Sci. Rep. 12, 15133 (2022).

Tostado-Véliz, M. et al. A fully robust home energy management model considering real time price and on-board vehicle batteries. J. Energy Storage 72, 108531 (2023).

Thomas, D., Deblecker, O. & Ioakimidis, C. S. Optimal operation of an energy management system for a grid-connected smart building considering photovoltaics’ uncertainty and stochastic electric vehicles’ driving schedule. Appl. Energy 210, 1188–1206 (2018).

Sehar, F., Pipattanasomporn, M. & Rahman, S. Coordinated control of building loads, PVs and ice storage to absorb PEV penetrations. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 95, 394–404 (2018).

Pan, T., Liu, H., Wu, D. & Hao, Z. Dual-layer optimal dispatching strategy for microgrid energy management systems considering demand response. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2695025 (2018).

Mansouri, S. A. et al. Bi-level mechanism for decentralized coordination of internet data centers and energy communities in local congestion management markets. In 2023 IEEE Int. Conf. Energy Technol. Futur. Grids, ETFG 2023 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1109/ETFG55873.2023.10407758.

Martinez-Pabon, M., Eveleigh, T. & Tanju, B. Optimizing residential energy management using an autonomous scheduler system. Expert Syst. Appl. 96, 373–387 (2018).

Barik, A. K. & Das, D. C. Integrated resource planning in sustainable energy-based distributed microgrids. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 48, 101622 (2021).

Sadeghian, O., Oshnoei, A., Mohammadi-ivatloo, B., Vahidinasab, V. & Anvari-Moghaddam, A. A comprehensive review on electric vehicles smart charging: Solutions, strategies, technologies, and challenges. J. Energy Storage 54, 105241 (2022).

Fatemi, S., Ketabi, A. & Mansouri, S. A. A multi-level multi-objective strategy for eco-environmental management of electricity market among micro-grids under high penetration of smart homes, plug-in electric vehicles and energy storage devices. J. Energy Storage 67, 107632 (2023).

Fatemi, S., Ketabi, A. & Mansouri, S. A. A four-stage stochastic framework for managing electricity market by participating smart buildings and electric vehicles: Towards smart cities with active end-users. Sustain. Cities Soc. 93, 104535 (2023).

Al-Ogaili, A. S. et al. Review on scheduling, clustering, and forecasting strategies for controlling electric vehicle charging: Challenges and recommendations. IEEE Access 7, 128353–128371 (2019).

Majidpour, M., Qiu, C., Chu, P., Pota, H. R. & Gadh, R. Forecasting the EV charging load based on customer profile or station measurement?. Appl. Energy 163, 134–141 (2016).

Wang, C., Grozev, G. & Seo, S. Decomposition and statistical analysis for regional electricity demand forecasting. Energy 41, 313–325 (2012).

Ebrahimi, A. & Moshari, A. Holidays short-term load forecasting using fuzzy improved similar day method. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 23, 1254–1271 (2013).

Panahi, D., Deilami, S., Masoum, M. A. S. & Islam, S. M. Forecasting plug-in electric vehicles load profile using artificial neural networks. In 2015 Australas. Univ. Power Eng. Conf. Challenges Futur. Grids, AUPEC 2015 1–6 (2015) https://doi.org/10.1109/AUPEC.2015.7324879.

Li, Y., Huang, Y. & Zhang, M. Short-term load forecasting for electric vehicle charging station based on niche immunity lion algorithm and convolutional neural network. Energies 11, 1253 (2018).

Zhu, J. et al. Electric vehicle charging load forecasting: A comparative study of deep learning approaches. Energies 12, 2692 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Deep-learning-based probabilistic forecasting of electric vehicle charging load with a novel queuing model. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 51, 3157–3170 (2021).

Xydas, E. S., Marmaras, C. E., Cipcigan, L. M., Hassan, A. S. & Jenkins, N. Forecasting electric vehicle charging demand using support vector machines. Proc. Univ. Power Eng. Conf. https://doi.org/10.1109/UPEC.2013.6714942 (2013).

Lu, K. et al. Load forecast method of electric vehicle charging station using SVR based on GA-PSO. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 69, 012196 (2017).

Duan, M., Darvishan, A., Mohammaditab, R., Wakil, K. & Abedinia, O. A novel hybrid prediction model for aggregated loads of buildings by considering the electric vehicles. Sustain. Cities Soc. 41, 205–219 (2018).

Zhu, J., Yang, Z., Guo, Y., Zhang, J. & Yang, H. Short-term load forecasting for electric vehicle charging stations based on deep learning approaches. Appl. Sci. 9, 1723 (2019).

Powell, S., Vianna Cezar, G., Apostolaki-Iosifidou, E. & Rajagopal, R. Large-scale scenarios of electric vehicle charging with a data-driven model of control. Energy 248, 123592 (2022).

Pantos, M. Exploitation of electric-drive vehicles in electricity markets. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 27, 682–694 (2012).

Gao, Q. et al. Charging load forecasting of electric vehicle based on Monte Carlo and deep learning. In 2019 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC) 1309–1314 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/iSPEC48194.2019.8975364.

Zhang, J., Yan, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, H. & Lv, G. Daily electric vehicle charging load profiles considering demographics of vehicle users. Appl. Energy 274, 115063 (2020).

Meng, Y., Mansouri, S. A., Rezaee Jordehi, A. & Tostado-Véliz, M. Eco-environmental scheduling of multi-energy communities in local electricity and natural gas markets considering carbon taxes: A decentralized bi-level strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 440, 140902 (2024).

Mansouri, S. A., Paredes, Á., González, J. M. & Aguado, J. A. A three-layer game theoretic-based strategy for optimal scheduling of microgrids by leveraging a dynamic demand response program designer to unlock the potential of smart buildings and electric vehicle fleets. Appl. Energy 347, 121440 (2023).

Mansouri, S. A., Maroufi, S. & Ahmarinejad, A. A tri-layer stochastic framework to manage electricity market within a smart community in the presence of energy storage systems. J. Energy Storage 71, 108130 (2023).

Zhou, X., Mansouri, S. A., Rezaee Jordehi, A., Tostado-Véliz, M. & Jurado, F. A three-stage mechanism for flexibility-oriented energy management of renewable-based community microgrids with high penetration of smart homes and electric vehicles. Sustain. Cities Soc. 99, 104946 (2023).

Nasir, M. et al. Two-stage stochastic-based scheduling of multi-energy microgrids with electric and hydrogen vehicles charging stations, considering transactions through pool market and bilateral contracts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48, 23459–23497 (2023).

Yi, T., Zhang, C., Lin, T. & Liu, J. Research on the spatial-temporal distribution of electric vehicle charging load demand: A case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 242, 118457 (2020).

Shivam, K., Tzou, J. C. & Wu, S. C. A multi-objective predictive energy management strategy for residential grid-connected PV-battery hybrid systems based on machine learning technique. Energy Convers. Manag. 237, 114103 (2021).

Hajiamoosha, P., Rastgou, A., Bahramara, S. & Bagher, S. M. International journal of electrical power and energy systems stochastic energy management in a renewable energy-based microgrid considering demand response program Demand response Thermal storage. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 129, 106791 (2021).

Goh, H. H. et al. Mid- and long-term strategy based on electric vehicle charging unpredictability and ownership estimation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 142, 108240 (2022).

Sharma, P., Mishra, P. & Mathur, H. D. Optimal energy management in microgrid including stationary and mobile storages based on minimum power loss and voltage deviation. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 31, e13182 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India, New Delhi, under the “Internet of things (IoT) Research of Interdisciplinary Cyber-Physical Systems Programme” with a Grant number: DST/ICPS/CLUSTER/IoT/2018/General.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS analyzed and conceptualized the idea and wrote the article. DB contributed to formulating and representing the results. HDM supervised and monitored the analysis performed in the paper. PM supervised and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, P., Bhattacharjee, D., Mathur, H.D. et al. Dual layer energy management model for optimal operation of a community based microgrid considering electric vehicle penetration. Sci Rep 14, 17499 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68228-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68228-7