Abstract

The lockbolt structure is essential in railway wagons, and a scientific lockbolt layout can ensure uniform load distribution, thereby preventing failure. However, current engineering lacks layout optimization methods that address multidimensional failure modes. This paper presents a new lockbolt structure layout optimization method based on submodel, parametric models, and a multi-strategy integrated NSGA-III (MSNSGA-III), adhering to the DVS EFB 3435-2 standard. This method simultaneously optimizes the number and spacing of lockbolts to prevent tensile, bearing, shear, and other static failure modes under specified load conditions. The proposed method was applied during the design phase of a container flatcar. Optimization results indicate that, compared to NSGA-III, this method achieves the best IGD and HV values across multiple complex test functions, demonstrating superior performance in solving complex Pareto front optimization problems. Additionally, the optimized lockbolt structure's safety margins increased by a maximum of 59.81%, passing the full vehicle strength test and significantly enhancing resistance to multidimensional failure modes. These results highlight the method's significant practical application value in addressing the optimization of railway wagon lockbolt structures under complex multidimensional failure modes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lockbolt technology, known as the Huckbolt® after its inventor, represents an alternative to conventional bolted joints1,2. Initially developed for the aerospace industry, lockbolts feature a unique ring groove structure that provides high preload and shear resistance, excellent corrosion resistance, and environmentally friendly assembly processes. This technology has been successfully adapted for application in railway wagons2,3, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Despite its widespread use, the unique connection mode of lockbolts introduces several problems. In traditional structural design, the lockbolt position is usually determined by engineering experience, and its specifications are determined according to the load conditions and relevant standards to ensure the lockbolt structure's reliability during rail vehicle operation4. However, the layout of lockbolts critically impacts load distribution. An optimized layout ensures uniform load distribution, thereby mitigating the risk of failures such as bearing or shearing5. Moreover, an efficient layout can reduce the number of lockbolts required, consequently decreasing overall weight and production costs5,6,7. Therefore, the optimization of lockbolt layouts is of significant importance for structural design and analysis.

Fastener layout primarily depends on empirical design methods5. However, some researchers have explored fastener layout optimization using topology optimization and meta-heuristic methods. Zhu et al.8 investigated the load distribution in fastener joints within aircraft structural design. They combined topology optimization with compliance design to validate the effectiveness of joint load constraint methods and proposed an optimization scheme for the shear load constraint of multi-fastener joints. Kim et al.9 utilized a genetic algorithm to optimize the design of double-bolted joints in cylindrical composite structures. They employed bolt spacing, edge distance, and composite lamination sequence as design variables to enhance the load-carrying capacity of the double-bolted joints. The optimized design was validated using Progressive Failure Analysis (PFA). Xiao et al.10 combined the Parthenon genetic algorithm (PGA) and the chaotic genetic algorithm (CGA) to propose the Parthenon chaotic genetic algorithm (PCGA). Addressing the issue of stress concentration at the hole edges of aerospace load-bearing connection structures, they optimized the layout of non-uniformly arranged bolt groups using bolt spacing as the design variable. The application of PCGA resulted in a 31.01% reduction in hole-edge stresses. Shen et al.11 combined parametric modeling with a genetic algorithm to optimize the angular acceleration of an electronic device. Using the positional coordinates of a single bolt as the design variable, their approach reduced the angular stress by 20.4%, thereby enhancing overall reliability. Cho et al.12 employed the response surface method (RSM) for the optimization analysis of bolt-hole edge stresses in composite structures. Using the positional coordinates of twin bolts as design variables, their approach reduced the maximum Von-Mises stresses by approximately 16%, thereby enhancing the overall load-supporting capacity of the structure. Chen et al.13 Chen et al.13 utilized an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm to optimize the overall stiffness of square components in heavy-duty CNC machine tools. By using process parameters such as preload, roughness, and other characteristics of the bolt population as design variables, they achieved global stiffness optimization. Lu et al.14 employed the Gray Wolf algorithm to optimize the bolt layout for nickel steel plate connectors. Using the positional coordinates of the asymmetric triangular bolt group as design variables, their optimization reduced the bolt hole circumferential Von-Mises stresses by 24% and the maximum bolt Von-Mises stresses by 12.5%. Zhou et al.15 constructed a finite element model of bolted joints based on CFRP/Al to analyze their failure modes. By using the NSGA-III algorithm to optimize the bolt connection layout, they increased the structural strength by 26.52%.

The above optimization methods primarily focus on determining the specific number of fasteners, utilizing relative positional coordinates as design variables, and aiming to minimize the Von-Mises stresses of the fasteners or the connected parts as the optimization objective. However, these fastener layout optimization methods are limited in that they cannot account for the impact of changes in the number of fasteners on the optimization results. Additionally, these methods typically rely on Von-Mises stress or a single evaluation criterion as the optimization objective, failing to comprehensively consider various failure modes of the fastener structure, such as the slipping failure of the lockbolt structure. Consequently, current optimization methods for fastener layouts still have significant limitations and face challenges in practical engineering applications.

To address the limitations of the aforementioned optimization methods, this paper first establishes the modeling methods, failure modes, and assessment methods for the lockbolt structure through tensile tests, destructive tests, and the guidelines provided in DVS EFB 3435-216,17. Secondly, this paper proposes an MSNSGA-III combining improved circle chaos mapping, dynamic crossover-mutation calibration strategy, and improved reference point selection strategy. Then, a new layout optimization method is presented that can simultaneously optimize the number and spacing of lockbolts while comprehensively evaluating multidimensional failure modes. This method utilizes submodel parametric modeling and combines the DVS EFB 3435-2 and the MSNSGA-III. Finally, using the fully lockbolt container flatcar as the research object for engineering application, multi-objective optimization is conducted to address high-stress areas and hazardous regions that may cause lockbolt structure failure. This process verifies the feasibility of the proposed layout optimization method and enhances the ability of the lockbolt structure in the region to resist multidimensional failure modes.

Modeling and assessment method

Validation of modeling methods

Tensile test

To ensure the accuracy of the numerical simulation results of the lockbolt structure, the modeling method needs to be verified experimentally. The lockbolt specimen installation process is based on the Chinese standard "General Technical Specification of Riveting Process for Railway Vehicle"18 (TB/T 2911-2016). As shown in Fig. 2, the lockbolt lap joint specimen consists of two plates and one lockbolt. The lockbolt specification is M16 × 50; the preload force is 85,000 N. The plate's material is Q450 high-strength weather-resistant steel with a 10 mm thickness. The plate overlap distance is 40 mm, and the clamping distance is 40 mm. The lockbolt and plate materials are the same as the fully lockbolt container flatcar. The red squares in Fig. 2 indicate the measurement points, totaling 24 in number. The measurement points are symmetrically positioned on the top and bottom surfaces, with points 1 to 12 located on the top surface and points 13 to 24 on the bottom surface.

The lockbolt tensile test is based on the Chinese standard "Ring groove rivet Assemblies Specifications"19 (GB/T 36993-2018). As shown in Fig. 3, the tests used an SDZ0100 electro-hydraulic servo dynamic and static fatigue testing machine. At room temperature, the quasi-static tensile test was carried out at a tensile rate of 1000N-min, and three groups of M16 lap joint specimens were subjected to quasi-static tensile tests. The average value of load-strain data of the measurement points was taken as the test results. The load-strain (\(F - \varepsilon\)) curves of each measurement point in the tensile test are shown in Fig. 6.

Modeling method research

This paper refers to the Beam & Coupling elements connection model20,21 in the simplified modeling method of bolt structure and applies it to the finite element modeling of lockbolt structure. To ensure the calculation accuracy, the finite element model of the lockbolt structure was established by using the 4-node shell element S4 in ABAQUS/Standard. The basic mesh size of both plates is 4 mm. All measurement points' locations are the shell elements' nodes.

According to the Chinese Standards TB/T 2911–201618, and International Standard DIN EN ISO 898-122 to determine the material parameters of M16 lockbolt: \(E = 450{\text{MPa}}\), \(\sigma_{0.2} = 640{\text{MPa}}\), \(\sigma_{m} = 800{\text{MPa}}\). In numerical simulations, the lockbolt constitutive model is modeled using a bilinear isotropic material model based on the above parameters. Figure 4 shows the Q450 constitutive model obtained from test measurements. Real stress and real strain consider the actual changing dimensions of the material during deformation, whereas nominal stress and nominal strain are based on the original, unchanging dimensions of the material. Considering the large deformation of the specimen, the real stress \(\sigma_{{{\text{True}}}}\) and the real strain \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{True}}}}\) are used in the numerical simulation, and their relationships with the nominal stress \(\sigma_{{{\text{Nom}}}}\) and the nominal strain \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{Nom}}}}\) are as follows.

The finite element model of the specimen is shown in Fig. 5. During the test, the testing machine clamped the specimen. To simplify the model, it was assumed that the clamping regions at both ends of the plate were rigid. Two reference points, RP-1 and RP-2 were defined at the centroid positions of the clamping regions of the two plates and coupled with the rigid region. Rigid constraints are applied to both reference points, where the displacement along the tensile direction is allowed at RP-2, and the same load as in the tensile test is loaded on PR-2. Numerical simulations were conducted using kinematic coupling and distributing coupling elements, respectively. Kinematic coupling is a constraint mechanism wherein the motion of slave nodes is entirely governed by a master node, ensuring that the relative displacement between the slave nodes and the master node remains constant. Conversely, distributing coupling involves the application of distributed forces or displacements from the master node to the slave nodes, permitting some degree of relative movement among the slave nodes while ensuring their average motion is influenced by the master node.

Verification of test and numerical simulation results

Figure 6a–d shows the strain results from the numerical simulation and tensile test, while Fig. 6e presents the strain error between these two methods. Based on the finite element model with Distributed Coupling, the load-strain curves at the measurement points around the edge of the lockbolt holes (measurement points 5, 6, 7, 17, 19, and 20) show significant deviations from the test data, with a root mean square error of 3.37e−4. In contrast, the numerical simulation results obtained using the finite element model based on Kinematic Coupling demonstrate good agreement with the test data, exhibiting an average deviation of 3% for 24 measurement points and a root mean square error of 6.23e−5. The experimental results fully validate the validity and accuracy of using the Beam & Kinematic Coupling elements for simulating the lockbolt structure.

Typical failure modes and assessment method

Typical failure modes

Many scholars have conducted in-depth and comprehensive analyses of the failure modes of fastener structures1,23,24,25,26, and other scholars have systematically generalized and summarized the failure modes of fastener structures. In this paper, combining the research results of many scholars, destructive tests were conducted for different lockbolt structures, and six typical failure modes were identified (Fig. 7), including tension failure, bearing failure, shear failure, slipping failure, the shank shear failure, and shank tension failure.

The failure mode analysis has several limitations and assumptions. First, the representativeness of the data samples is insufficient, and the complexity of environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and corrosion affecting the lockbolt structure has not been fully considered. Additionally, the simplification of experimental conditions and the use of specific materials limit the comprehensiveness of the analysis. The study assumes that the lockbolt structure operates under design conditions, each failure mode is independent, materials are uniform and isotropic, and the structure is regularly maintained and defect-free. However, in practical applications, factors such as overload, interactions between failure modes, material heterogeneity, and inadequate maintenance can all affect failure modes. These limitations and assumptions need further validation and improvement in future research.

Assessment method

The DVS EFB 3435-2 is introduced to evaluate the six typical failure modes of the lockbolt structure. In the field of mechanical and rolling stock engineering in Germany, approximately 68% of removable joints are designed and evaluated with reference to VDI 223027,28, which has been used worldwide for 40 years as a guideline for the design and evaluation of high-strength bolts25. This standard provides a systematic specification for the strength assessment method of lockbolts, considering factors such as the connection form between the lockbolt and the clamped part, dimensions, and friction coefficients. Compared to traditional assessment methods, it offers a comprehensive evaluation of multiple failure modes of the lockbolt structure2. It is widely used in regions such as ships and rolling stock.

GLIENKE1,2,3 et al. and SCHWARZ25 et al. have demonstrated the accuracy of the DVS EFB 3435-2 standard. In addition, some scholars have already used DVS-EFB 3435-2 in the railway industry4. The DVS EFB 3435-2 assessment process based on the finite element method is shown in Fig. 8.

As shown in Fig. 8, the DVS EFB 3435-2 standard defines six safety margins, which correspond to one or more of the typical failure modes, and these safety margins can be used to effectively predict and assess the typical failure behavior of the lockbolt structure under different load conditions. Therefore, this paper assesses the failure behavior of the lockbolt structure using \(S_{F}\),\(S_{P}\),\(S_{G}\),\(S_{A}\),and \(S_{L}\) of DVS EFB 3435-2. These safety margins are calculated as follows:

(1) Safety margin against exceeding the yield point \(S_{F}\):

The safety margin against exceeding the yield point \(S_{F}\) is used to assess the tensile safety of the lockbolt structure. The aim is to ensure that the lockbolt structure works safely and reliably under actual operating conditions, i.e., the maximum bolt load \(F_{S\max }\) does not exceed the tensile strength of the bolt \(R_{M}\), which corresponds to the shank tension failure (Fig. 7f). The expression is as follows:

where \(F_{M}\) is the assembly preload; \(\Phi_{n}\) is the load factor; \(F_{A\max }\) is the axial load; \(\Delta F_{vth}{\prime}\) is the change in the preload as a result of a temperature different from room temperature; \(\sigma_{Z\max }\) is the tensile stress in the lockbolt in the working state; \(A_{S}\) is the stress cross-section of the lockbolt thread, \(d_{S} = d_{3}\); \(R_{M}\) is the tensile strength of the lockbolt.

(2) Safety margin against surface pressure \(S_{P}\):

Safety margin against surface pressure \(S_{P}\) is used to assess the safety of the contact stresses on the surfaces of the clamped parts of the lockbolt structure and to ensure that the surfaces of the clamped parts are not subject to problems such as compression collapse, which corresponds to the bearing failure (Fig. 7b). The expression is as follows:

where: \(F_{SA\max }\) is the maximum axial additional bolt load; \(A_{P\min }\) is the minimum of the bolt head or nut bearing area;\(P_{M/B\max }\) is the surface pressure in assembled state and working state; \(P_{G}\) is the limiting surface pressure.

(3) Safety margin against slipping \(S_{G}\):

Safety margin against slipping \(S_{G}\) is used to assess the slip phenomenon of the clamped parts of the lockbolt structures under transverse loading, which corresponds to the slipping failure (Fig. 7d). The expression is as follows:

where: \(F_{Q\max }\) is the transverse load; \(q_{F}\) is the number of force-transmitting inner interfaces involved in possible slipping/shearing of the bolt; \(\mu_{T\min }\) is the coefficient of friction at the interface; \(\alpha_{A}\) is the tightening factor, \(\alpha_{A} = 1.05\).

(4) Safety margin against shearing \(S_{A}\):

Safety margin against shearing \(S_{A}\) is used to assess the safety of a lockbolt structure under transverse loading \(F_{Q\max }\), to ensure that the lockbolt does not suffer shank shear failure (Fig. 7e). The expression is as follows:

where: \(A_{\tau }\) is the shearing area during transverse loading; \(\tau_{B} /R_{M}\) is the shear strength ratio; \(d_{\tau }\) is the diameter of the shearing cross-section, \(d_{\tau } = d_{3}\).

(5) Safety margin against breaing pressure \(S_{L}\):

Safety margin against breaing pressure \(S_{L}\) is used to assess the reliability of the lockbolt structure under transverse loading, to ensure that the clamped parts do not suffer from tension failure and shear out failure (Fig. 7a,c). The expression is as follows:

where: \(h\) is the thickness of the clamped parts; \(R_{p0,2P}\) is the 0.2% proof stress of the clamped parts.

Layout optimization method

Parametric model of the lockbolt structure

A parametric model is a method in finite element analysis where the geometry of the model is controlled by a set of parameters, allowing for flexible adjustments and optimization of the design. This paper utilizes Pycharm Professional 2023 and Python 3.11 for the secondary development of ABAQUS 2021, establishes a parametric modeling and automated solution process for the general-purpose lockbolt lap structures shown in Fig. 9a. Figure 9b shows the main parameters to be determined for the parametric model, where \(p\) is the lockbolt spacing, \(q\) is the number of lockbolts, \(l\) is the specification of the clamped parts, and \(e\) is the distance of the lockbolt from the edges of the clamped parts.

The parametric modeling and solution automation process is shown in Fig. 10a,b,c, which is mainly composed of a user definition and input module, a Python driver module, and an ABAQUS output module. After defining the input parameters, Python can drive the ABAQUS/Standard program based on specified parameters to execute steps such as component modeling, component assembly, coupling, meshing, load, and solution, where the lockbolt structure is meshing using the Beam & Kinematic Coupling element in Section "Verification of Test and Numerical Simulation Results". After the solution is completed, Python automatically extracts the Beam element loads \(F_{x}\), \(F_{y}\), \(F_{z}\), \(M_{x}\), \(M_{y}\), and \(M_{{\text{z}}}\) in the ABAQUS result file (.odb) and calculates the \(S_{F}\), \(S_{P}\), \(S_{G}\), \(S_{A}\), and \(S_{L}\) of the lockbolt based on the DVS EFB 3435-2. Furthermore, mesh refinement is conducted during meshing, particularly focusing on the stress concentration region around the hole. This automated procedure enhances the efficiency of the parametric modeling solution and optimization analysis for the lockbolt structure.

MSNSGA-III

A genetic algorithm is an optimization technique inspired by natural selection and genetics, used to find optimal or near-optimal solutions to complex problems. It starts by generating an initial population of random solutions, followed by evaluating each solution based on a fitness function that measures its quality. The best solutions are selected to reproduce, combining parts of two parent solutions to create new ones, a process known as crossover. Additionally, some parts of the new solutions are randomly modified to maintain diversity, known as mutation. This process of evaluation, selection, crossover, and mutation is repeated over several generations until an optimal solution is found or a stopping condition is met. Genetic algorithms are advantageous due to their global search capability, flexibility in application to various problems, and parallelism, allowing for the simultaneous processing of multiple solutions, thus improving efficiency. NSGA-III is a multi-objective genetic algorithm based on the second generation of non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm NSGA-II 29, which introduces reference points to transform large-scale problems into uniformly distributed trade-off solution sets. Although it reduces the complexity of NSGA-II and improves the computational efficiency of large-scale optimization problems, it still suffers from the issues of poor utilization of decision-making information in the population space, difficulty in determining the division of the reference points, and over-focusing on the local optimum. To address these drawbacks, this paper proposes the MSNSGA-III (Multi-Strategies) with the following improvement strategies.

Improved circle Chaos mapping population initialization

Population initialization refers to generating a set of random initial solutions at the start of a genetic algorithm to provide a starting point for the optimization process. Random generation of traditional NSGA-III populations tends to cluster the initial populations, which leads to uneven distribution of populations and thus affects the subsequent optimization results. This paper introduces a chaotic mapping initialization population method for this problem. The chaotic mapping randomness and traversal can ensure the dispersion and uniformity of the initial population. The standard chaotic mappings include Logistic, circle, and Sine chaotic mapping30,31. Wu et al. improved the circle chaotic mapping method to obtain a more uniformly distributed initial population with high coverage of chaotic values32. To get a more excellent initial population, this paper carries out population initialization based on the improved circle chaotic mapping with the expression:

where: \(x_{j}^{i}\) is the position of the \(i_{{{\text{th}}}}\) individual in the \(j_{{{\text{th}}}}\) dimension; \(ud_{i}\) is the upper limit in the \(j_{{{\text{th}}}}\) dimension; \(ld_{i}\) is the lower limit in the \(j_{{{\text{th}}}}\) dimension; \(z_{j}^{i}\) is the chaos parameter of the \(i_{{{\text{th}}}}\) individual in the \(j_{{{\text{th}}}}\) dimensional, initial value is rand(); \(\mu = 0.2\);\(\tau = 0.5\);\(\rho = 3.14\);\(\theta = 1.75\).

Dynamic crossover-mutation calibration strategy

In genetic algorithms, crossover and mutation involve combining parts of two parent solutions to create new solutions and randomly altering some parts of these new solutions to maintain diversity. Using fixed crossover and mutation probabilities will lead to slower genetic algorithm convergence and fall into the local optimum, resulting in subpar search outcomes33. The traditional NSGA-III algorithm sets the crossover and mutation probabilities as constant values, which may destroy the excellent individuals in the process of evolution and cause the phenomenon of population "degradation"34. Therefore, to address the above problems, this paper proposes a dynamic crossover and mutation calibration strategy: before the simulated binary crossover (SBX) and polynomial mutation (PM), their probabilities for crossover \(p_{c}\) and mutation \(p_{m}\) are dynamically calibrated by multidimensional adaptation \(Fit\). The specific formulas are as follows (Fig. 11):

where: \(Fit_{\min }\) is the minimum multidimensional fitness in the population; \(Fit_{{{\text{avg}}}}\) is the average multidimensional fitness in the population; \(Fit^{\prime}\) is the smaller multidimensional fitness of the two individuals in the crossover; \(Fit^{*}\) is the smaller multidimensional fitness of the individual to be mutated; \(fit_{i,j}\) is the fitness of the \(i_{{{\text{th}}}}\) individual in the \(j_{{{\text{th}}}}\) dimension; \(p_{1}\), \(p_{2}\), \(p_{3}\), and \(p_{4}\) is the const.

Improved reference point selection strategy

In genetic algorithms, reference point selection strategies are used in multi-objective optimization to guide the population towards optimal solutions. These strategies select representative reference points based on theoretical models, historical data, or problem-specific criteria to enhance the algorithm's convergence and maintain diversity. The conventional NSGA-III employs the boundary-crossing construction weight method for reference point selection. This strategy effectively addresses issues with uniformly continuous Pareto fronts like DTLZ1, UF8, WFG1, etc. However, it is less effective in solving problems featuring discontinuous or inaccessible real Pareto fronts. This limitation becomes apparent when optimizing the lockbolt structure where the true Pareto front surface cannot be obtained (The true Pareto front refers to the set of all optimal solutions that are not dominated by any other solution in multi-objective optimization.). To address the above issues, this study proposes an improved reference point selection strategy based on the reference point selection strategy35. This strategy discerns the evolutionary stage of the population through the quartile distribution feature information of the population in the decision space. Then, it selects the reference point on the hyperplane through the distribution feature of the population in the objective space (The objective space is the set of all objective function values, representing how solutions perform on multiple objectives.).

Entropy reduction refers to the process of selecting split points to decrease the uncertainty or entropy of a dataset, making the data purer. During population evolution, the population changes from disorder to order and gradually converges, which is the course of entropy reduction. Hence, the entropy reduction \(\Delta e^{t}\) and threshold \(\Delta \mu\) of two neighboring generations can characterize the population's evolutionary stage \(S_{{{\text{mode}}}}\), as depicted in Eqs. (20) and (21). If \(\left| {\Delta e^{t} } \right| > \Delta \mu\), it indicates that the population has entered a state of positive evolution \(S_{{{\text{explode}}}}\), the algorithm performs "Explode" behavior, and the population gradually explodes in the search space (The search space contains all possible solutions, which is the set of all potential solutions.). If \(\left| {\Delta e^{t} } \right| < \Delta \mu\), it indicates that the population exits the positive evolutionary stage \(S_{{{\text{explode}}}}\) and enters the negative evolutionary stage \(S_{{{\text{explore}}}}\), it means that the algorithm performs "Explore" behavior. The population stops exploding and converges gradually in the search space.

where: \(t\) is the current evolutionary number of the population; \(e_{t}\) is the entropy value; \(inf_{i}\) is the standardized interquartile difference of the population; \(\Delta mid^{t}\) is the standardized median difference of the populations; \(\overline{inf}\) is the standardized interquartile difference for a uniformly distributed population, \(\overline{inf} = 0.5\); \(D\) is the dimension of the decision space; \(N\) is the population size.

As the population evolves, individuals tend to be associated with the reference line through the true Pareto front. Therefore, the traditional reference point selection strategy can be improved by counting the number of associations between the reference points and the individuals in the population in each generation to assess the importance of the reference points. Hence, the reference points with more associations with the individuals can be retained more. The process of the improved reference point selection strategy is as follows:

-

(1)

The set of reference points \(Z\) with each dimension divided into \(p\) is selected according to the population size \(N\), The number of reference points in \(Z\) is \(H_{p}\), \(H_{p}\) satisfies:\(H_{p} \ge 1.2N\) and \(H_{p - 1} < 1.2N\) .

-

(2)

Determine the evolutionary stage \(S_{{{\text{mode}}}}\) based on entropy reduction \(\Delta e^{t}\) and the threshold \(\Delta \mu\) between neighboring generations.

-

(3)

When the population is in the "Explode" stage, \(S_{{{\text{mode}}}} = S_{{{\text{explode}}}}\), counting the sum of the number of associated individuals per generation \(Z_{{{\text{sum}}}}\) in the set of reference points \(Z\) .

-

(4)

When the population is in the "Explore" stage, \(S_{{{\text{mode}}}} = S_{{{\text{explore}}}}\), select the \(N\) reference points with the highest number of associations to create a new set of reference points, denoted as \(Z_{n}\).

Algorithmic process

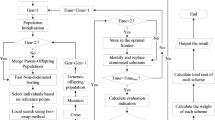

Combining the above circle chaotic mapping population initialization, dynamic crossover mutation calibration strategy, and the improved reference point selection strategy, the specific steps of the MSNSGA-III algorithm are as follows (annotations indicate the position and Eq. of strategies):

Performance verification and analysis

In evolutionary algorithms and optimization problems, test functions are standardized problems used to evaluate algorithm performance. They provide consistent and repeatable benchmarks to help researchers validate and compare the effectiveness and robustness of different algorithms. To validate the efficacy of the MSNSGA-III, the DTLZ1, DTLZ2, DTLZ4, DTLZ5, DTLZ6, and DTLZ7 functions from the DTLZ36 test set are chosen for experimentation and compared with the NSGA-III. To ensure the fairness of the evaluation, the population size is \(N = 100\), and the maximum generations is \(G_{\max } = 30\) of the two algorithms. The crossover probability is 0.8, and the mutation probability is 0.1 of the NSGA-III. The test platform is PlateEMO 4.537 of MATLAB R2023b. Inverted generation distance (IGD) 38 and Hype volume (HV) 39, which can reflect the convergence and distribution of the algorithm, are used as primary performance evaluation metrics to gauge the algorithms' effectiveness. The IGD indicator calculates the average distance from reference points to the nearest solution. Reference points far from all solutions have a larger IGD, thus reflecting both the convergence and diversity of the solution set. The HV indicator calculates the sum of the hypervolume formed by all nondominated solutions and the Nadir Point. For the same test function, each algorithm runs independently 30 times to calculate the average and standard deviation of the results. The non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test compares the two algorithms with a significance level set at 5%. In Table 1, the symbol "+" indicates that the MSNSGA-III is significantly better than other algorithms, "−" indicates significant inferiority to different algorithms, and "=" indicates no difference between the two algorithms.

From the comparison results in Table 1, the MSNSGA-III algorithm achieved the optimal IGD and HV on all 6 test functions. This indicates that the MSNSGA-III algorithm exhibits the best performance in terms of convergence and diversity on the five test functions. This paper uses box plots to represent the statistical results of the two algorithms on various test functions. The outer upper and lower limits of the box plot represent the maximum and minimum of the samples, the inner upper and lower boundaries represent the upper and lower quartiles, the central red line within the box represents the median, the central blue dashed line represents the mean, and the red dots represent outliers. The box plots for the IGD and HV indicators (Figs. 12, 13) further demonstrate the advantages of the MSNSGA-III in terms of mean, median, quartiles, and outliers. This indicates that the MSNSGA-III is more stable and robust than the NSGA-III. This conclusion further demonstrates the effectiveness of the circle chaotic mapping, dynamic crossover-mutation calibration strategy, and the improved reference point selection strategy.

Optimization model

Design variables are parameters in the optimization process that can be adjusted and modified to influence and improve the performance of a design. For a lockbolt structure, as shown in Fig. 9a, the design variables are defined as follows: the number and space of lockbolts along the length direction of the plate is \(q_{1}\) and \(p_{1}\), And the number and space of lockbolts along the width direction of the plate is \(q_{2}\) and \(p_{2}\), as specifically shown in Fig. 9b and Eq. (22).

The optimization objective is the specific goal that an optimization process aims to achieve. For the six failure modes of the lockbolt structure: tension failure, bearing failure, shear out failure, slipping failure, shank shear failure, and shank tension failure, this method defines the optimization objective: the parametric model \(F_{PM}\) outputs a set of minimum safety margins, including against exceeding the yield point \(S_{F\min }\), surface pressure \(S_{P\min }\), slipping \(S_{G\min }\), shearing \(S_{A\min }\), and breaing pressure \(S_{L\min }\). The optimization objectives are selected to reinforce the lockbolt structure's capacity to withstand multidimensional failure modes.

The objective function is a mathematical expression that quantitatively represents the optimization objective, guiding the optimization process by evaluating the performance of different design variables. Objective function: the squared error between the minimum \(S_{\min }\) and tolerable safety margin \(\left[ S \right]\), as shown in Eqs. (23) and (24). This objective function is used to measure the difference between \(S_{\min }\) and \(\left[ S \right]\), rapidly converging as \(S_{\min }\) approaches \(\left[ S \right]\), which \(\left[ S \right]\) can be adjusted according to different industries and standards. The definition of this objective function is based on the following factors: the number of lockbolts is positively correlated with the minimum margins, and defining the objective function to approach infinity would result in a significant increase in the total number of lockbolts in the optimization results. Excessive lockbolt holes can lead to stress concentration in the clamped parts, causing fatigue issues40,41. Additionally, an excessive number of lockbolt holes can increase production costs. Therefore, to align the optimized results with actual engineering requirements and avoid over-design or under-design, the objective function is defined as the square error between \(S_{\min }\) and \(\left[ S \right]\).

Constraints are limitations or conditions imposed on the optimization process, defining the feasible region within which the solution must lie. Constraints: for structures with multiple fasteners, inadequate fastener spacing, and edge distances can decrease fatigue life40. Therefore, it is essential to consider the minimum allowable distances of fastener spacing \(p\) and edge \(e\) during the optimization process. Different countries, regions, or industries have specific and varying requirements for the minimum allowable distances of fasteners in steel structures41,42,43,44. The DIN EN 1993–1-345 and DIN EN 1993–1-846 are used to determine \(e > 1.5d_{h}\) and \(p > 2.2d_{h}\). Additionally, it is necessary to ensure that the clamped parts \(\sigma_{{{\text{Von}} \cdot {\text{Mises}}}}\) do not exceed the allowable stress \(\left[ {\sigma_{{{\text{Von}} \cdot {\text{Mises}}}} } \right]\) during the optimization process, as shown specifically in Eq. (25) and (26).

The expression of this optimization method is as follows:

Find:

Minimize:

where:

Subject to:

where:

With bounds:

The layout optimization process of the lockbolt structure combining the submodel method, parametric modeling method, DVS EFB 3435-2, and the MSNSGA-III is shown in Fig. 14. The specific steps are as follows:

(1)Conduct finite element analysis on the overall engineering model according to load conditions. Utilize DVS EFB 3435-2 to identify regions with inadequate safety margins or high stresses for optimization.

(2)Extract the displacements of the boundary nodes of the identified region and construct a submodel.

(3)The parametric modeling solution method outlined in Section "Parametric Model of the Lockbolt Structure" is used to parameterize the submodel of the optimized regions, allowing for the consideration of various parameter combinations during optimization to achieve the optimal layout solution.

(4)Set the parameters of optimization and constraint to establish the optimization model.

(5)Based on advanced production experience, determine the number and spacing of temporary lockbolts to establish a group of high-quality individual samples. Introduce these high-quality individuals into the initial population, generated using improved circle chaotic mapping. Each initial individual undergoes interference checks and repair operations in conjunction with constraint parameters.

(6)Perform optimization using the MSNSGA-III algorithm presented in Section "MSNSGA-III".

(7)Select the optimal solution based on the design variables and optimization objectives from the optimization results.

Engineering applications

Submodel and parametric model of the flatcar

This paper proposed lockbolt structure layout optimization method has been applied in the design stage of the fully lockbolt structure container flatcars produced by CRRC Qiqihar Rolling Stock Co., Ltd. The prototype of the fully lockbolt container flatcar, along with its geometric model and finite element model, is shown in Fig. 15. The flatcar is primarily composed of main beams, side beams, a bottom plate, a floor, and a container locking device. The material used is Q450 high-strength weather-resistant steel (material parameters are shown in Fig. 4). The finite element model of the flatcar is constructed using shell elements and solid elements, while the lockbolt structure is modeled using Beam & Kinematic Coupling elements as described in section "Verification of Test and Numerical Simulation Results". The model consists of a total of 4,398,878 elements and 1,798,706 nodes.

According to the Chinese standard "Strength Design and Test Accreditation Specification for Rolling Stock-Car body" TB/T 3550.247, the combined load conditions are set: the self-weight of the flatcar is 22.4t; mass points of 9t are applied to each of the 8 locking seats of the body to simulate the payload weight of 72t; the torsional load 40kN·m is applied at the body side bearing; the tensile load 1920kN is applied at the front and rear body bolster, and the lateral force is applied in the form of a lateral acceleration of 0.1g. All loads are applied simultaneously. Constrain is applied at the center plate. The calculation results of Von-Mises stress under combination load conditions are shown in Fig. 16. The region where the main beam is connected to the floor is a stress concentration region. After calculation, the minimum safety margins of the lockbolts group in this region are shown in Table 3, where the safety margin against slipping \(S_{G\min }\) is below the specified tolerable margin of 1.2; the safety margin against surface pressure \(S_{P\min }\) is below the specified tolerable margin of 1.0.

This region is selected for further optimization analysis using the proposed layout optimization method for the lockbolt structure. First, as shown in Fig. 17a,b, the flatcar model is trimmed to identify the boundary nodes of the submodel. Figure 17c and 16d display the boundary displacements, with the X-axis representing the sequence of nodes and the Y-axis showing the displacements \(U\) or rotational displacements \(U_{R}\). These boundary node displacements are extracted and linearly interpolated, and the interpolated displacements are then used as boundary conditions for the parametric model. Finally, the submodel method and techniques described in Section "Parametric model of the lockbolt structure" are applied to establish the parametric model. To ensure the parametric model's results are accurate, the boundary should be truncated far from the stress concentration areas. Figure 17e illustrates the boundary conditions of the parametric model, while Fig. 17f presents the Von-Mises stress results for the parametric model with the specified input parameter \(q_{1} = 2,q_{2} = 2,p_{1} = 117,p_{2} = 67\).

Layout optimization results

In the optimization process, the population size \(N = 100\), and the number of generations \(G_{\max } = 30\). Figure 18 shows the relationship between the optimization objective and the generations, whose coordinates are the safety margins, the generations, and the use of the standardized optimization objective \({{[S]} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{[S]} S}} \right. \kern-0pt} S}\). Our analysis reveals that the population evolves and continues to optimize as the number of generations gradually increases. The optimization objective \(S\) finally converges to a tolerable safety margin \(\left[ S \right]\). The optimization process shows a good trend in agreement with the expected design, highlighting the significant effect of the method. Further analysis of the relationship between the minimum objective functions for Paradigm Normalization and the generations (Fig. 19) shows that the minimum objective functions continue to decrease. After 21 generations, the minimum of each objective function no longer decreases significantly, and the algorithm approximates the true Pareto optimal solution of the optimization problem.

Figure 20a,b demonstrate the distribution of design variables of the initial populations and Pareto solutions. The horizontal and vertical coordinates correspond to \(p_{1}\) and \(p_{2}\), with the color of the molecules corresponding to \(q_{2}\), and the size of the molecules corresponding to \(q_{1}\). The design variables of the initial populations exhibit a disordered and discrete distribution state without a clear clustering trend. The design variables of the Pareto solutions exhibit a significant clustering distribution towards three distribution characteristics (as shown in Table 2). Figure 20c,d respectively demonstrate the distribution of optimization objectives of the initial populations and Pareto solutions. The horizontal axis represents the safety margins \(S\), and the vertical axis represents the standardized optimization objective \({{[S]} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{[S]} S}} \right. \kern-0pt} S}\). Each line on the Fig. 20c,d corresponds to an individual. Each optimization objective's range significantly decreases through box plot comparison, approaching the tolerable safety margins \(\left[ S \right]\). Statistical analysis further validated these findings. A paired T-test was conducted to compare the optimization objectives before and after the optimization process. The results showed that the maximum p-value for the safety margins (\(S_{P}\)) was 4.8e−2, which is less than 0.05. This confirms that the optimization effectively narrowed the range and improved the overall safety margins. Additionally, an ANOVA test revealed significant differences in safety margins before and after optimization.

In this paper, considering the manufacturing cost, the design parameters that satisfy the requirements of tolerable safety margin, and the minimum total number of lockbolts in the Pareto solution are selected as the optimization results. The optimal design variables \(q_{1} = 3,q_{2} = 2,p_{1} = 57,p_{2} = 117\) and optimization objectives \(S_{F\min } = 1.306\), \(S_{P\min } = 1.050\), \(S_{G\min } = 1.202\), \(S_{A\min } = 4.525\) and \(S_{L\min } = 115.698\) were determined based on Fig. 20b,d. To validate the optimization results and the accuracy of the parametric model, we verified the calculated results. As shown in Table 3, we optimized the original finite element model using the optimal design variables and analyzed the error between the parametric model and the optimized finite element model, with a maximum error of 11.51%, which meets engineering requirements. Additionally, we compared the minimum safety margins of the lockbolts among the original finite element model, the parametric model, and the optimized finite element model. After optimization, \(S_{P\min }\) is improved by 19.60%, \(S_{G\min }\) by 22.29%, \(S_{A\min }\) by 58.13%, and \(S_{L\min }\) by 59.81%. The safety margins have been significantly improved and all exceeded the tolerable safety margins \(\left[ S \right]\). Applying these optimization results, the prototype container flatcar passed the strength tests, and the lockbolt structure did not exhibit the failure modes described in Section "Typical failure modes".

These results demonstrate the engineering significance of the proposed lockbolt structure layout optimization method. By optimizing the number and spacing of rivets under specific load conditions, the reliability of the lockbolt structure is significantly enhanced, thereby preventing potential failures.

Sensitivity analysis

To further analyze the sensitivity of the design variables on optimization objectives, this study employs Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to perform multiple samplings of the design variables \(q_{1}\), \(q_{2}\), \(p_{1}\) and \(p_{2}\). Considering their interactions, we use the SOBOL method for second-order sensitivity analysis to quantitatively evaluate the impact of different variable interactions on the optimization results. The results of the second-order sensitivity analysis are shown in Fig. 21, where each subplot represents an optimization objective. The color blocks in the subplots illustrate the second-order sensitivity of each design variable considering interactions, with the color scale indicating the strength of the sensitivity.

By comparing the second-order sensitivity results of different optimization objectives, it can be observed that the second-order sensitivities of the design variables show significant differences under different optimization objectives. Some variable combinations exhibit significant second-order sensitivities for specific objectives. For instance, the positive interaction between \(q_{1}\) and \(q_{2}\) for \(S_{P}\) is significant, as is the positive interaction between \(q_{1}\) and \(p_{1}\) for \(S_{G}\). The negative interaction between \(q_{2}\) and \(p_{2}\) for \(S_{G}\), \(S_{A}\), and \(S_{L}\) is significant. Since both \(S_{A}\) and \(S_{L}\) are calculated through the transverse load \(F_{Q\max }\) (Eq. (13) and Eq. (15)), their second-order sensitivity distributions are highly consistent. In summary, the interactions of various variables have a significant impact on the optimization results. Considering these interactions can lead to more reliable and efficient optimization.

Discussions

Despite the significant advantages of the MSNSGA-III algorithm in multi-objective optimization problems, it has some weaknesses. Firstly, the algorithm may face performance bottlenecks when handling high-dimensional problems. As the number of objectives increases, the complexity of the search space rises sharply, leading to slower convergence rates. Additionally, since the algorithm relies on a dynamic crossover mutation calibration strategy, the initial parameter settings significantly impact the results. These parameters may require multiple adjustments for different problems, increasing the difficulty and time cost of using the algorithm.

The current layout optimization method mainly focuses on optimizing the lockbolt structure for six static failure modes, without considering fatigue failure. This limitation implies that the optimization results may not be ideal for long-term use or under dynamic load conditions.

Future research will include incorporating fatigue failure modes into the existing layout optimization method to develop a more comprehensive optimization model, improving the reliability of optimization results for long-term use and dynamic load conditions; combining deep learning with dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the complexity of the search space and overcome the algorithm's performance bottlenecks in high-dimensional problems; and testing and validating the layout optimization method in industries such as construction and shipbuilding, where lockbolt structures are widely used, to evaluate its practical application value.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Combined with the tensile test of the lockbolt structure, the Beam & Coupling elements are used to study the simplified modeling method. The results show that the finite element model constructed based on Distributed Coupling has significant deviations at the measurement points around the edge of the lockbolt holes, whereas the model constructed based on Kinematic Coupling exhibits good consistency. The numerical simulation agrees with the experimental results, with an average deviation of 3% and a root mean square error of 6.23e−5. This modeling method can effectively simulate the mechanical behavior of the lockbolt structure, providing a reliable and simplified modeling solution for the numerical simulation of lockbolt structures in engineering applications.

-

(2)

Many destructive tests have been carried out on a variety of lockbolt structures, and six typical failure modes of lockbolt structures have been identified: tension failure, bearing failure, shear failure, slipping failure, shank shear failure, and shank tension failure.

-

(3)

The MSNSGA-III algorithm is proposed by introducing several key innovations: improved circle chaotic mapping for population initialization, a dynamic crossover mutation calibration strategy, and an improved reference point selection strategy. These improvements address deficiencies in NSGA-III, such as uneven distribution of initial populations, premature convergence to local optima, and poor utilization of decision-making information within the population space. Specifically, the improved circle chaotic mapping ensures a more uniform and dispersed initial population, the dynamic crossover mutation calibration strategy enhances convergence and prevents degradation, and the improved reference point selection strategy effectively guides the population in complex optimization scenarios. Experiments show that MSNSGA-III achieves optimal IGD and HV metrics across all six test functions, demonstrating superior convergence and distribution in feasible regions. It excels in handling complex Pareto fronts and challenging optimization problems, marking a significant advancement over NSGA-III algorithm .

-

(4)

This paper proposes a new layout optimization method using submodel technology, parametric modeling, DVS EFB 3435-2, and MSNSGA-III. This method can simultaneously optimize the number and spacing of lockbolts, comprehensively evaluate multiple failure modes of the lockbolt structure, and has been verified through engineering application. The results show that after increasing the number of lockbolts from \(1 \times 4\) to \(2 \times 3\) and adjusting the spacing of lockbolts from 50 to 57mm and 117mm, the minimum safety margins in the selected region exceeded the tolerable safety margins \(\left[ S \right]\). Specifically, \(S_{P\min }\) improved by 19.60%, \(S_{G\min }\) by 22.29%, \(S_{A\min }\) by 58.13%, and \(S_{L\min }\) by 59.81%. These improvements significantly enhanced the ability of the selected region of lockbolt structures to resist multidimensional failure modes. It provides a feasible idea for optimizing railway wagon locking structure layout and has important engineering application value.

Data availability

The results provided in this paper are generated by MATLAB and Python codes developed by the authors. The codes can be available upon request by contacting the corresponding author via email. The container flatcar geometric and finite element models provided in this paper are unavailable due to confidentiality reasons. All authors consent to the publication of this manuscript.

References

Glienke, R., Schwarz, M., Wegener, F. & Flügge, W. Steigerung der Tragfähigkeit in Exzentrisch Beanspruchten Verbindungen Durch den Einsatz von Schließringbolzensystemen 74–80 (2017).

Glienke, R., Schwarz, M., Ebert, A., Blunk, C. & Wanner, M. C. Joints with lockbolts in steel structures—Part 1: Lockbolt technology. Steel Constr. 13, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/stco.202000011 (2020).

Glienke, R., Schwarz, M., Ebert, A., Blunk, C. & Wanner, M. C. Joints with lockbolts in steel structures – Part 2: Design and execution. Steel Constr. 13, 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/stco.202000039 (2020).

Yu, S. & Fu, M. Reliability analysis of typical lockbolt connection structure for railway wagons. Mech. Eng. Technol. 12, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.12677/met.2023.122012 (2023).

Croccolo, D. et al. Optimization of Bolted joints: A literature review. Metals 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/met13101708 (2023).

Xia, T., Yao, W., Xu, L. & Zou, J. Metamodel-based optimization of the bolted connection of a wing spar considering fatigue resistance. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G: J. Aerosp. Eng. 230, 805–814. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954410015598792 (2015).

Kradinov, V., Madenci, E. & Ambur, D. R. Application of genetic algorithm for optimum design of bolted composite lap joints. Compos. Struct. 77, 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.06.009 (2007).

Zhu, J.-H., Hou, J., Zhang, W.-H. & Li, Y. Structural topology optimization with constraints on multi-fastener joint loads. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 50, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-014-1071-5 (2014).

Kim, M., Kim, Y., Kim, P. & Park, J. Design optimization of double-array bolted joints in cylindrical composite structures. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 17, 332–340. https://doi.org/10.5139/ijass.2016.17.3.332 (2016).

Xiao, W., He, E. & Hu, Y. A new method of optimizing Bolts layout in connector based on improved genetic algorithm. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 35, 414–421 (2017).

Shen, B., Pan, Z. W., Lin, H. & Li, W. Z. Bolt layout optimization design based on genetic algorithm. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 576, 1. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/576/1/012005 (2019).

Cho, H. Optimization of joint hole position design for composite beam clamping. Kor. Soc. Manuf. Process Eng. 18, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.14775/ksmpe.2019.18.2.014 (2019).

Chen, K. et al. Optimization of Square-shaped Bolted Joints Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Eksploatacja i Niezawodność – Maintenance and Reliability 25, 1. https://doi.org/10.17531/ein/168487 (2023).

Lu, X. et al. Triangular position multi-bolt layout structure optimization. Applied Sciences 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13158786 (2023).

Zhou, C., Huang, C., Chen, Y., Zhang, W. & Wang, L. Performance of a novel resistant rock bolt with periodic energy absorption and release: theory and experiment. Acta Geotechnica 19, 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01943-z (2023).

DVS-EFB 3435-1:2021: Lockbolt systems (DVS-VERLAG GmbH, Verlag für Schweissen und Verwandte Verfahren, German, 2021).

DVS-EFB 3435-2:2016: Lockbolt systems - Calculation of connections according to Eurocode 3 and VDI 2230-Part 1 (DVS-VERLAG GmbH, Verlag für Schweissen und Verwandte Verfahren, German, 2016).

TB/T 2911:2016: General technical specification of riveting process for railway vehicle (Standards Press of China, Beijing, 2016).

GB/T 36993:2018: Ring groove rivet assemblies - Specifications (Standards Press of China, Beijing, 2018).

Gray, P. J. & McCarthy, C. T. A global bolted joint model for finite element analysis of load distributions in multi-bolt composite joints. Compos. Part B: Eng. 41, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2010.03.001 (2010).

Wu, X. et al. Study on the analytical model of bending deformation for spliced glass beams with stainless steel bolts. Structures 59, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105786 (2024).

DIN EN ISO 898-1:2013: Mechanical properties of fasteners made of carbon steel and alloy steel - Part 1: Bolts, screws and studs with specified property classes - coarse thread and fine pitch thread (German Institute for Standardisation, German, 2013).

Ebert, A., Dörre, M. & Glienke, R. Behaviour of lockbolts in slip-resistant connections for steel structures. Steel Constr. 10, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/stco.201710043 (2017).

née Meyer, M. H., Schwarz, M., Glienke, R., Schwerdt, D. & Henkel, K.-M. in The 33rd International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference.

Schwarz, M., Glienke, R., Wegener, F., Blunk, C. & Henkel, K. M. Calculation of lockbolt joints in mechanical engineering. Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik 51, 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/mawe.201900143 (2020).

Selvaraj, S., Chan, T.-M. & Young, B. Influence of geometry on failure modes of PFRP single bolted connections. Eng. Struct. 274, 115078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115078 (2023).

VDI 2230 Blatt 1:2015: Systematic calculation of highly stressed bolted joints - Joints with one cylindrical bolt (Verlag des Vereins Deutscher Ingenieure, German, 2015).

VDI 2230 Blatt 2:2014: Systematic calculation of highly stressed bolted joints - Multi bolted joints (Verlag des Vereins Deutscher Ingenieure, German, 2014).

Jain, H. & Deb, K. An evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point based nondominated sorting approach, part II: Handling constraints and extending to an adaptive approach. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 18, 602–622. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEVC.2013.2281534 (2014).

Herbadji, D., Derouiche, N., Aissa, B. & Herbadji, A. A tweakable image encryption algorithm using an improved logistic chaotic map. Traitement du Signal 36, 407–417. https://doi.org/10.18280/ts.360505 (2019).

Belazi, A. et al. Improved Sine-Tangent chaotic map with application in medical images encryption. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 66, 103131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2022.103131 (2022).

Wu, C. & Cong, M. in 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI). 930–933.

Kramer, O. in Genetic Algorithm Essentials (ed Oliver Kramer) 47–54 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Yi, J.-H., Deb, S., Dong, J., Alavi, A. H. & Wang, G.-G. An improved NSGA-III algorithm with adaptive mutation operator for Big Data optimization problems. Fut. Gen. Comput. Syst. 88, 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2018.06.008 (2018).

Huantong, G., Zhongbin, D., Tianlei, W. & Ke, X. Improved NSGA-III algorithm based on reference point selection strategy. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 33, 191–201. https://doi.org/10.16451/j.cnki.issn1003-6059.202003001 (2020).

Deb, K., Thiele, L., Laumanns, M. & Zitzler, E. in Evolutionary Multiobjective Optimization: Theoretical Advances and Applications (eds Ajith Abraham, Lakhmi Jain, & Robert Goldberg) 105–145 (Springer London, 2005).

Tian, Y., Zhu, W., Zhang, X. & Jin, Y. A practical tutorial on solving optimization problems via PlatEMO. Neurocomputing 518, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2022.10.075 (2022).

Coello, C. A. C. & Cortés, N. C. Solving multiobjective optimization problems using an artificial immune system. Genet. Program. Evol. Mach. 6, 163–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10710-005-6164-x (2005).

Zitzler, E. & Thiele, L. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: A comparative case study and the strength Pareto approach. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 3, 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.797969 (1999).

Yu, D., Chen, Y. & Gao, Y. Study on fatigue property tests and holistic life assessment method for single bolted joints. Zhongguo Jixie Gongcheng/China Mechanical Engineering 24, 2747–2752. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-132X.2013.20.009 (2013).

DIN EN 1993-1-9:2010: Eurocode 3: Design of steel structures - Part 1-9: Fatigue (German Institute for Standardisation, German, 2010).

GB 50017:2017: Code for design of steel structures (Standards Press of China, Beijing, 2017).

ANSI/AISC 360:2022: Specification for Structural Steel Buildings (American Institute of Steel Construction, American, 2022).

AS 4100:2020: Steel structures (Standards Australia, Australia, 2020).

DIN EN 1993-1-3:2010: Eurocode 3: Design of steel structures - Part 1-3: General rules - Supplementary rules for cold-formed members and sheeting (German Institute for Standardisation, German, 2010).

DIN EN 1993-1-8:2010: Eurocode 3: Design of steel structures - Part 1-8: Design of joints (German Institute for Standardisation, German, 2010).

TB/T 3550.2:2019: Strength design and test accreditation specification for rolling stock-Car body-Part 2:Car body of freight wagons (Standards Press of China, Beijing, 2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial and experimental support provided by the CRRC Qiqihar Rolling Stock Co., Ltd.

Funding

This research was supported by the CRRC Qiqihar Rolling Stock Co., Ltd., under grant number 2021CHA014: CRRC Science and Technology Research and Development Fund Grant Program "Research on key technology of equal life span of railway wagons".

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. X.L.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition. Q.Z.: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision. X.H.: Validation, Writing –review & editing. S.W.: Data curation, Project administration. Q.M.: Data curation, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Li, X., Zhang, Q. et al. Research and engineering application of layout optimization for lockbolt structures in railway wagons considering multidimensional failure modes based on MSNSGA-III. Sci Rep 14, 19557 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70424-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70424-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Study on the service behavior of rivets connected with brake pads of high speed trains

Scientific Reports (2025)