Abstract

Nutritional status assessment, including amino acids, carnitine, and acylcarnitine profile, is an important component of diabetes care management, influencing growth and metabolic regulation. A designed case–control research included 100 Egyptian participants (50 T1DM and 50 healthy controls) aged 6 to 18 years old. The participants' nutritional status was assessed using the Body Mass Index (BMI) Z-score. Extended metabolic screening (EMS) was performed using a high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectroscopy system to evaluate the levels of 14 amino acids, free carnitine, and 27 carnitine esters. T1DM children had considerably lower anthropometric Z-scores than the control group, with 16% undernutrition and 32% short stature. Total aromatic amino acids, phenylalanine, phenylalanine/tyrosine ratio, proline, arginine, leucine, isoleucine, free carnitine, and carnitine esters levels were considerably lower in the diabetic group, suggesting an altered amino acid and carnitine metabolism in type 1 diabetes. BMI Z-score showed a significant positive correlation with Leucine, Isoleucine, Phenylalanine, Citrulline, Tyrosine, Arginine, Proline, free carnitine, and some carnitine esters (Acetylcarnitine, Hydroxy-Isovalerylcarnitine, Hexanoylcarnitine, Methylglutarylcarnitine, Dodecanoylcarnitine, Tetradecanoylcarnitine, and Hexadecanoylcarnitine). HbA1c% had a significant negative correlation with Total aromatic amino acids, Branched-chain amino acid/Total aromatic amino acids ratio, Glutamic Acid, Citrulline, Tyrosine, Arginine, Proline, and certain carnitine esters (Propionylcarnitine, Methylglutarylcarnitine, Decanoylcarnitine, Octadecanoylcarnitine and Octadecenoylcarnitine), suggest that dysregulated amino acid and carnitine metabolism may be negatively affect the glycaemic control in children with TIDM. In conclusion, regular nutritional assessments including EMS of T1DM patients are critical in terms of diet quality and protein content for improved growth and glycemic management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a complex metabolic condition defined by chronic hyperglycemia caused by abnormalities in insulin production, action, or both. Poor insulin secretion and/or diminished tissue insulin responses cause inefficient insulin action on target tissues, resulting in glucose, lipid, and protein metabolic problems1.

Pediatric undernutrition is the disparity between nutrient need and consumption, resulting in an accumulative deficiency in protein, micronutrients, and energy which can have a deleterious impact on normal growth and development2.

Nutritional disorders such as obesity and chronic undernutrition have been connected with diabetes mellitus3,4. Children with type 1 diabetes should have their nutritional status examined frequently because they are in a growing stage and liable to malnutrition owing to the chronic and burdensome nature of the condition or the concomitant occurrence of related autoimmune diseases such as celiac disease5,6.

The human body's protein metabolism is a continuous process that includes both protein breakdown and protein synthesis. Lean body mass can be increased or lost as a result of changes in either of these processes, or both. Braziuniene et al.,7 in their study concluded that insulin's primary anabolic effect on protein metabolism in adolescents with type 1 diabetes is to prevent whole-body proteolysis with no evidence of insulin's ability to increase protein synthesis in these adolescent participants, even when they were adequately fed.

Abnormal amino acid metabolism impairs the body's balance, preventing growth and development. Furthermore, amino acids have a role in gene expression, hormone synthesis and secretion, food metabolism, oxidative stress protection, immunity, reproduction, growth, and child development8.

Carnitine, a water-soluble tiny molecule similar to a vitamin, transports long-chain fatty acids from the cytosol to the mitochondria for β-oxidation and energy production. L-carnitine has been proven to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics, as well as increasing membrane stability, insulin sensitivity, dyslipidemia, and protein nutrition9.

Is there a link between amino acid plasma levels, carnitine, and acylcarnitines, nutritional status, and glycemic control in Type 1 diabetes patients, and are there any differences when compared to healthy controls? So the rationale and the target of this study is to analyze these metabolomics and to assess their relationship with the nutritional status of type 1 diabetic patients as well as indicators of glycemic control to help us understand the current situation of our cases and better address, treat, and improve quality of life in those vulnerable patients.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

Based on the standards established in the Declaration of Helsinki, case–control research was conducted with 100 Egyptian children and adolescents aged 6–18 years, with 50 diagnosed with type 1 diabetes10 and 50 healthy sex and age-matching control groups during the study period from January 2023 to December 2023. They were chosen from the outpatient pediatric endocrinology clinics of Qena University Hospitals, South Valley University, Upper Egypt, following permission from Qena University's ethics committee with an ethical approval code (SVUMEDPED02542212532). A formal agreement was obtained from participants above the age of 16 and all children's caregivers under the age of 16.

Cases with concomitant chronic illness, chronic diabetes complications, cases associated with autoimmune disease, or vegetarian patients were all eliminated from the analysis.

The sample size was set using the proportion difference approach level to ensure 80% power and 95% confidence level in the significance (type 1 error), control-to-case ratio of 1:1, and supposed odds ratio of ≥ 211. So at least 48 participants should be presented in each group and we include 50 patients and 50 controls.

Clinical evaluation of the included children

Precise medical data were obtained from all participants including age, gender, residence, nutritional history, family history of type 1 diabetes, age of diabetic onset, history of recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis12, history of recurrent unexplained hypoglycemia, and an inquiry about type and doses of injected insulin was obtained. Anthropometric evaluations were completed and plotted correctly for patients wearing light clothing and without shoes. Using a conventional stadiometer, height was measured to the closest 0.1 cm, and an electronic scale was used to determine weight to the closest 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was computed as kg/m2. The participants' nutritional status was evaluated using World Health Organisation (WHO) standard techniques for children aged 5 to 19 years13. The BMI was transformed to Z-scores using WHO AnthroPlus 1.0 and classed as obese (> + 2SD), overweight (≥ 1 to + 2SD), normal (≥ − 2 to ≤ + 1SD), and underweight (< − 2 SD). The weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ) and height-for-age Z-score (HAZ) are derived by subtracting the observed value from the reference population's median value and dividing it by its standard deviation14. Short stature was considered with a height that was ≥ 2 standard deviations lower than the mean for children of the same gender and chronological age15.

Complete systematic respiratory, cardiac, abdominal, and neurological evaluation was performed for the studied groups.

Laboratory workup

A 4 mL of venous blood was obtained from each participant into an EDTA tube for the laboratory evaluation after a 12-h fast. HbA1c was measured using a Cobas c311 (provided by Hitachi, Roche Diagnostics, Germany). A normal HbA1c (glycated hemoglobin) result should be 4.5–5.6%, and children with T1DM should have a level less than 7.5% to be considered well-controlled16. Plasma-free amino acids, carnitines (CN), and acylcarnitines (AcylCNs) were determined using a high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectroscopy (HPLC–ESI–MS) system (supplied by Waters Company, England) as described in a previously published work17. Briefly, The amino acid assays were performed using stable isotope internal standards (ISTDs) from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. A total of 14 amino acids were measured (Leucine, Isoleucine, Methionine, Phenylalanine, Valine, Alanine, Aspartic acid, Glutamic acid, Citrulline, Ornithine, Tyrosine, Arginine, Glycine, and Proline) and classified as essential, non-essential, and conditionally essential amino acids18. Phenylalanine/tyrosine ratio, Total aromatic amino acids "AAA" (Tyrosine + Phenylalanine), Total branched-chain amino acids "BCAA"(Valine + Leucine + Isoleucine), and branched-chain amino acids (BCAA)/aromatic amino acids (AAA) ratios were calculated. Also, a total of 28 carnitine levels were assessed. Free L-carnitine is referred to as C0 or FC, while acylcarnitines were divided into three classes19, based on the number of carbon atoms in the acyl group chain: short-chain acylcarnitines, medium-chain acylcarnitines, and long-chain acylcarnitines.

Statistical analysis

Data input and analysis were conducted with Statistical Package for Social Science version 22. Data were tested for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro– Wilk tests and were found to be normally distributed. Numbers, percentages, means, and standard deviations were employed to present the information. Chi-squared and student t-tests were utilized. Pearson's correlation coefficient was employed. statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Cases were collected correspondingly with the guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics committee of South Valley University (Ethical approval code: SVUMEDPED02542212532). Informed written consent was taken from participants ≥ 16 years old and from the parents of the younger participants for participation in the study and publication.

Results

Clinical data of the participants

This study included 50 patients with T1DM with a mean age of 12.58 years ± 2.5; females represent the major percentage 54.0%. Cases compared to 50 age- and sex-matched healthy children as a control group, with a mean age of 12.54 years ± 2.0; 25 males (50.0%) and 25 females (50.0%). Comparing the two groups, there are no significant differences concerning age and sex, but significantly lower values were observed as regards anthropometric data Z-scores (weight, height, and MBI Z-scores) among the included TIDM children with 16 cases (32%) having short stature, 8 cases (16%) having undernutrition, and 2 cases (4%) had overweight (Table 1), indicating a high prevalence of malnutrition among T1DM patients.

Laboratory data of the included studied groups

Evaluation of the levels of Plasma amino acid profiles and some of their derivatives among the study groups showed that Children with T1DM had significantly lower levels of Leucine & Isoleucine (146.70 ± 29.48 μmol/l), Phenylalanine (57.90 ± 5.79 μmol/l), Phenylalanine/Tyrosine ratio (0.57 ± 0.03), Total aromatic amino acids "AAA" (158.62 ± 13.32 μmol/l), Arginine (21.68 ± 4.31 μmol/l), and Proline (161.0 ± 58.10 μmol/l) compared to the control group with p-Value < 0.05 as shown in Table 2, indicating deficiency of some amino acids (most of them are essential amino acids that can’t be supplied by the human body and should be supplied in their diet) among T1DM children.

The current study found that children with T1DM exhibited significantly lower levels of free carnitine (41.48 ± 11.30 μmol/l) compared to (49.44 ± 11.06) in the control group. Short-chain acylcarnitines levels revealed also that T1DM had lower values versus the control group for Propionylcarnitine, Malonylcarnitine, Butyrylcarnitine, Hydroxybutyrylcarnitine, Methylcrotonylcarnitine, Hydroxy-Isovalerylcarnitine, Glutarylcarnitine, and Hexanoylcarnitine with p-Value < 0.05. Medium-chain acylcarnitines Decenoylcarnitine, Dodecanoylcarnitine, Hydroxytetradecanoylcarnitine, and Long-chain acylcarnitines Hexadecanoylcarnitine, Hexadecenoylcarnitine, Hydroxyhexadecanoylcarnitine, Octadecenoylcarnitine, Hydroxyoctadecanoylcarnitine, and Hydroxyoctadecenoylcarnitine had also significantly lower levels than the control group (Table 3), indicating that dysregulated lipid metabolism in T1DM could be related to a lack of plasma carnitine and some of its esters among those patients.

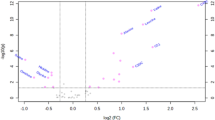

Correlation between plasma free amino acids (PFAAs) with HbA1c% and BMI-Z score in diabetic patients

A significant negative correlation was figured out between HBA1c% and the following amino acids; Total aromatic amino acids "AAA", BCAA/AAA ratio, Glutamic Acid, Citrulline, Tyrosine, Arginine, and Proline. BMI Z-score positively correlated with Leucine, Isoleucine, Phenylalanine, Citrulline, Tyrosine, Arginine, and Proline Table 4, indicating the possible contributory role of some amino acids availability with the nutritional status and the degree of glycemic control among children with T1DM.

Correlation between carnitine and acylcarnitines derivatives with HbA1c% and BMI Z-score in T1DM

A significant negative correlation was detected between HBA1c % and the following derivatives; Propionylcarnitine, Methylglutarylcarnitine, Decanoylcarnitine, Octadecanoylcarntine, and Octadecenoylcarnitine. BMI Z-score had a significant positive correlation with Free carnitine, short-chain acylcarnitines (Acatylcarnitine, Hydroxy-Isovalerylcarnitine, Hexanoylcarnitine, and Methylglutarylcarnitine), Medium-chain acylcarnitines (Dodecanoylcarnitine, and Tetradecenoylcarnitine), and long-chain acylcarnitines Hexadecenoylcarnitine (C16) as shown in Table. 5. Thus carnitine and some of its esters are significantly linked to the nutritional status and glycemic control among diabetic children.

Discussion

Nutritional management is a key component of diabetes care and education. Different countries have vastly different cultures and socioeconomic positions, which impact and dominate eating patterns. Although the strong evidence for nutritional needs in diabetic children, the scientific evidence basis for many elements of diabetic nutritional management is still developing20.

Despite improvements in medical care and therapy for T1DM children, their growth is still suboptimal, which is most likely due to persistent metabolic dysregulation21. The current study demonstrated that children and adolescents with T1DM exhibited impaired nutritional status with weight, height, and MBI-Z scores significantly lower in comparison to the healthy group; 8 cases (16%) had undernutrition, 2 cases (4%) had overweight, and 16 cases (32%) having short stature. BMI Z-score showed a significant positive correlation with Tyrosine, Phenylalanine, Citrulline, Proline, Arginine, free carnitine, short-chain acylcarnitines (C2, C5-OH, C6, and C6DC), Medium-chain acylcarnitines (C12, and C14), and long-chain acylcarnitines C16.

Several investigations found that T1DM patients had considerably lower anthropometric measurements than the general population22,23. Hussein et al.23 found that 21.42% of children and adolescents with T1DM have wasting and 38.09% have short stature. Bizzarri et al.24 observed that reduced growth velocity, together with a decline in height standard deviation from the onset of diabetes to reach final adult height, has been a constant finding in T1DM, as both pre-pubertal growth velocity and the pubertal growth surge have been reported to be lower. Furthermore, Khadilkar et al.25 found 10.9% and 27.1% rates of wasting and short stature, respectively. Aljuhani et al.26 found 6.9% wasting and 11.9% short stature and Kayirangwa et al.16 found that stunting was prevalent in 30.9% of type 1 diabetic subjects they investigated. These variances may be attributed to changes in sample size and population variables between studies.

Plasma amino acid concentrations are tightly regulated by homeostatic mechanisms and their concentration changes have been reported in a variety of disorders, including metabolic diseases27 and malnutrition28.

The essential amino acids are derived from proteins involved in the growth process. Furthermore, the body cannot entirely or effectively synthesize its carbon skeleton de novo, thus it must be acquired by dietary intake to attain adequate sufficiency. Adequate energy intake and high-quality protein are two elements that promote linear growth in children29. Semba et al.30 discovered that stunted children had reduced serum concentrations of all nine essential amino acids, as well as non-essential amino acids (asparagine, glutamate, serine) and conditionally essential amino acids (arginine, glycine, glutamine).

In the current study, cases had an elevated HBA1c% (9.87 ± 1.13). Plasma amino acid profiles and some of their derivatives among the study groups revealed that children with T1DM had significantly lower levels of Phenylalanine, Phenylalanine/Tyrosine ratio, Total aromatic amino acids "AAA", Leucine & Isoleucine, Proline, and Arginine than the control group; suggesting an altered amino acid metabolism in type 1 diabetes. HBA1c levels were also found to be adversely connected with Tyrosine, Total aromatic amino acids, Branched-chain amino acid/Total aromatic amino acid ratio, Proline, Glutamic Acid, Arginine, and Citrulline.

Insulin deficit inhibits protein synthesis and promotes protein breakdown, hence amino acid metabolism may be changed in diabetes mellitus31. This may explain our findings about the high HBA1c% and its relationship to amino acid levels.

We found lower significant levels of free carnitine and carnitine esters levels in the diabetic group with HBA1c% negatively correlated with C3, C6DC, C10, C18, and C18:1. BMI Z-score positively correlated with free carnitine, C2, C5-OH, C6, C6DC, C12, C14, and C16.

Multiple authors have documented reduced plasma levels of L-carnitine in Type 1 diabetes patients32,33 and type 2 diabetes34. Morgane et al.35 discovered that free L-carnitine levels in individuals with newly diagnosed or long-term T1DM were considerably lower than in the healthy control group. La Marca36 and his colleagues found that levels of acyl-carnitines C2, C3, C5OH, C4, C16, and C18 were considerably lower in the cases compared to controls. Furthermore, the sum of the total measured amino acid concentrations tended to be lower in cases compared to controls.

L- carnitine is an important nutritional element supplemented in animal food as its endogenous synthesis is insufficient to satisfy metabolic needs, and a High-Fat Diet (HFD) can increase carnitine and its metabolite production37. Its supplementation enhances nitrogen balance by increasing protein formation or decreasing protein breakdown, preventing apoptosis, inhibiting inflammatory responses under pathological conditions, improves a variety of key pathways involved in pathological skeletal muscle loss38,39.

Diabetes disrupts glucose metabolism, resulting in a negative energy balance, especially during insulin shortage. A brief period of insulin deprivation affects mitochondrial function, protein synthesis, and enzyme activity40.

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed in support of the favorable effect of carnitine on glucose metabolism: it intensifies the mitochondrial oxidation of long-chain acyl-CoA, the aggregation of which would otherwise lead to insulin resistance in the muscle and heart; modifying the expression of glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes; adjusting the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; provoking of the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis; and IGF-1 signaling41.

Future studies are required to evaluate the effect of adequate nutrition treatment with particular essential amino acids & carnitine supplementation, when combined with other diabetes management strategies, can improve anthropometric parameters and glycemic control or not.

This study has some limitations as it was a single-center study with a small sample size and a lack of follow-up data on the included cases. Additional suggestions for performing a big multicenter study with a greater sample size to reinforce the study results. Despite this restriction, the fact that this study was conducted prospectively utilizing a standardized approach rather than a review of patients' files gives it a significant advantage.

Conclusion

Determining dietary requirements and assessing the sufficiency of normal growth in minors with T1DM is a critical issue. T1DM patients had considerably lower anthropometric Z-scores than the control group, with 16% undernutrition and 32% short stature. The findings of the current study indicated lower levels of plasma amino acid levels (especially essential amino acids that can’t be synthesized in the human body and must be obtained through diet) and L-carnitine levels with significant association with lower anthropometric parameters and poor glycemic controls among the included participants with type 1 diabetes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, after obtaining the permission of our institute.

References

Libman, I. et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 23(8), 1160–1174. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.13454 (2022).

Mehta, N. M. et al. Defining pediatric malnutrition: A paradigm shift toward etiology-related definitions. J. Parent. Enter. Nutrit. 37(4), 460–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607113479972 (2013).

Hu, F. B. Globalization of diabetes: The role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care 34(6), 1249–1257. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-0442 (2011).

Uwaezuoke, S. N. Childhood diabetes mellitus and the “double burden of malnutrition”: An emerging public health challenge in developing countries. J Diabetes Metab. 6(597), 2. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6156.1000597 (2015).

American Diabetes Association. Nutrition Recommendation and Principles for People with Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 23(1), S43–S46 (2000).

Baseer, K. A., Mohammed, A. E., Elwafa, A. M. & Sakhr, H. M. Prevalence of celiac-related antibodies and its impact on metabolic control in Egyptian children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. BMC Pediatrics 24, 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04575-8 (2024).

Braziuniene, I. et al. Effect of Insulin With Oral Nutrients on Whole-Body Protein Metabolism in Growing Pubertal Children With Type 1 Diabetes. Pediatric Research. 65(1), 109–112. https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181894911 (2009).

Wu, G. Amino acids: Metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids 37(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-009-0269-0 (2009).

Bene, J., Hadzsiev, K. & Melegh, B. Role of carnitine and its derivatives in the development and management of type 2 diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 8, 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-018-0017-1 (2018).

American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 45(1), S17–S38. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S002 (2022).

Charan, J. & Biswas, T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research?. Indian J Psychol Med. 35(2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.116232 (2013).

Mays, J. A. et al. An evaluation of recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis, fragmentation of care, and mortality A cross Chicago, Illinois. Diabetes Care. 39(10), 1671–1676. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0668 (2016).

World Health Organization. BMI-for-age (5–19 years). In Growth Reference Data for 5–19 Years; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry (1995) Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical Report Series No. 854. World Health Organization, Geneva.

Polidori, N., Castorani, V., Mohn, A. & Chiarelli, F. Deciphering short stature in children. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 25(2), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2040064.032 (2020).

Kayirangwa, A., Rutagarama, F., Stafford, D. & McCall, N. Assessment of growth among children with Type 1 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study of factors contributing to stunting. J. Diabetes Metab. 9, 4. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6156.1000793 (2018).

Hassan, M. H. et al. Profile of plasma free amino acids, carnitine and acylcarnitines, and JAK2v617f mutation as potential metabolic markers in children with type 1 diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Chromatogr 37, e5747. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmc.5747 (2023).

Dietzen, D. J. & Willrich, M. A. V. Amino acids, peptides, and proteins. In Tietz Textbook of Laboratory Medicine 7th edn (eds Rifai, N. et al.) 31 (Elsevier, 2023).

Zhao, S. et al. The association between Acylcarnitine metabolites and cardiovascular disease in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00212 (2020).

Annan, S. F. et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Nutritional management in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes. 23(8), 1297–1321. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.13429 (2022).

Mitchell, D. M. Growth in patients with type 1 diabetes. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 24(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000310 (2017).

Dohan, B. R., Habib, S. & Abd, K. A. Nutritional Status of Children and Adolescents with Type1 Diabetes Mellitus in Basra. Med. J. Basrah Univ. 39(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.33762/mjbu.2021.127780.1027 (2021).

Hussein, S. A., Ibrahim, B. A. & Abdullah, W. H. Nutritional status of children and adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Baghdad: a case-control study. J. Med. Life. 16(2), 254–260. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2022-0233 (2023).

Bizzarri, C. et al. Residual beta-cell mass influences growth of prepubertal children with type 1 diabetes. Horm Res Paediatr. 80(4), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355116 (2013).

Khadilkar, V. V. et al. Growth status of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 17, 1057–1060. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.122623 (2013).

Aljuhani, F. M. et al. Growth status of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Curr. Pediatr. Res. 22(3), 249–254 (2018).

Yamaguchi, N. et al. Plasma free amino acid profiles evaluate risk of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension in a large Asian population. Environ. Health Prev. 22(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-017-0642-7 (2017).

Ortega, P. A., van Gelder, N. M., Castejón, H. V., Gil, N. M. & Urrieta, J. R. Imbalance of individual plasma amino acids relative to valine and taurine as potential markers of childhood malnutrition. Nutr. Neurosci. 2(3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.1999.11747275 (1999).

Tessema, M. et al. Associations among high-quality protein and energy intake, serum transthyretin, serum amino acids and linear growth of children in Ethiopia. Nutrients 10(11), 1776. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111776 (2018).

Semba, R. D. et al. Child stunting is associated with low circulating essential amino acids. EBioMedicine 6, 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.030 (2016).

Travé, T. D. et al. Amino acid plasma profile in children with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Compl. 2(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.31487/j.JDMC.2020.01.01 (2020).

Coker, M. et al. Carnitine metabolism in diabetes mellitus. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 15(6), 841–849. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem.2002.15.6.841 (2002).

Mamoulakis, D., Galanakis, E., Dionyssopoulou, E., Evangeliou, A. & Sbyrakis, S. Carnitine deficiency in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 18, 271–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1056-8727(03)00091-6 (2004).

Ramazani, M., Qujeq, D. & Moazezi, Z. Assessing the levels of L-carnitine and total antioxidant capacity in adults with newly diagnosed and long-standing type 2 diabetes. Can. J. Diabet. 43(1), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2018.03.009 (2019).

Morgane, D. S., Abougabal, K. M., Abdel Aziz, M. M. & El-Gayed, A. S. Assessment of serum L-carnitine level in children with type 1 diabetes. Alexandria J. Pediatr. 34(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/ajop.ajop_7_21 (2021).

la Marca, G. et al. Children who develop type 1 diabetes early in life show low levels of carnitine and amino acids at birth: Does this finding shed light on the etiopathogenesis of the disease?. Nutr. Diabetes. 3, e94. https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2013.33 (2013).

Kepka, A. et al. Preventive role of l-carnitine and balanced diet in Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 12, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12071987 (2020).

Montesano, A., Senesi, P., Luzi, L., Benedini, S. & Terruzzi, I. Potential therapeutic role of L-carnitine in skeletal muscle oxidative stress and atrophy conditions. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015(2015), 646171. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/646171 (2015).

Ringseis, R., Keller, J. & Eder, K. Mechanisms underlying the anti-wasting effect of l-carnitine supplementation under pathologic conditions: Evidence from experimental and clinical studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 52, 1421–1442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-013-0511-0 (2013).

Hebert, S. L. & Nair, K. S. Protein and energy metabolism in type 1 diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 29(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2009.09.001 (2010).

Ringseis, R., Keller, J. & Eder, K. Role of carnitine in the regulation of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity: Evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies with carnitine supplementation and carnitine deficiency. Eur J Nutr. 51(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-011-0284-2 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to everybody who participated in this study; the children who were the participants of this study, the technicians who helped in the laboratory analysis, and the doctors who participated in the collection of the data. Without their help, this study couldn’t have been completed.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by H.M.S., M.H.H., A.E.A., N.I.R., R.H.A.-A., and R.T. laboratory workup was performed by M.H.H. and A.S.G. The first draft of the manuscript was written by H.M.S. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.”

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakhr, H.M., Hassan, M., Ahmed, A.EA. et al. Nutritional status and extended metabolic screening in Egyptian children with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep 14, 21055 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70660-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70660-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Biochemical study on microRNAs (miR-410, miR-133 and miR-582) in Egyptian type 1 diabetic patients

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2025)