Abstract

Soybean is an economically important crop for animal and human nutrition. Currently, there is a lack of information on the effects of Trichoderma harzianum and Purpureocillum lilacinum on INTACTA RR PRO transgenic soybean plants. The present study evaluated the application of T. harzianum and P. lilacinum under field conditions. The results revealed a significant increase in soybean yield at 423 kg ha−1 in response to the application of P. lilacinum compared with the control treatment. In addition, the application of P. lilacinum promoted a significant increase in phosphorus levels in the plant leaves, and there were significant correlations between the increase in taxon abundance for the genus Erwinia and productivity and the average phosphorus and nitrogen content for the plant leaves, for the taxon Bacillus and nitrogen content and productivity, and for the taxon Sphingomonas and nitrogen content. The Bradyrhizobium taxon was identified in the P. lilacinum treatment as a taxon linking two different networks of taxa and is an important taxon in the microbiota. The results show that the application of the fungus P. lilacinum can increase the productivity of soybean INTACTA RR PRO and that this increase in productivity may be a function of the modulation of the microbiota composition of the plant leaves by the P. lilacinum effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soybean crops are highly important worldwide because of the large supply of vegetable protein for animal production, such as swine and poultry production, and are also used for human consumption in addition to its derivatives, such as soybean oil1. Brazil and the USA are the largest soybean producers in the world2. Soybeans are the fifth most produced food in the world and allow farmers high profitability for the maintenance of agricultural activities3.

Soybean crops, like other agricultural crops, face several challenges in order to remain productive and profitable. The problems faced in soybean production are the occurrence of several pathogens and diseases requiring the application of fungicides4 and insecticides due to the occurrence of several important pests that cause great economic losses5. In addition, there are other factors that hinder soybean production, including various environmental stresses, such as salinity, due to recurrent localized fertilization, such as fertigation at soybean production sites that do not have well-distributed rainfall6, water stress due to a lack of rainfall7; and the presence of heavy metals and contaminants in crop soils, which promote significant losses in productivity8 and high temperatures9, and consequently, a reduction in agricultural area and a loss of productive potential.

Owing to the large quantities produced in large arable areas, soybean production requires large amounts of mineral fertilizers that, when used indiscriminately, promote salinization and contamination of soils, contamination of surface waters with eutrophication, and contamination of groundwater with the leaching of nutrients into groundwater10.

Plants maintain a diverse and structured community of microorganisms known as the plant microbiota, which inhabits all accessible plant tissues. These plant-associated microbiomes offer several advantages to host plants, on the other hand, plants provide numerous habitats that support the growth and proliferation of a wide range of microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, protists, nematodes, and viruses (collectively known as the plant microbiota). These microorganisms often have intricate relationships with plants and play a crucial role in increasing their productivity and well-being in natural environments11. The recruitment of various microbial populations from the soil to plant roots is crucial for plant health. In addition, interactions among the microbes in the root microbiome play a vital role in plant resilience to soil-borne pathogens12.

Fungi have diverse and wide genetic and metabolic variabilities, producing several secondary metabolites that can be used in biotechnological processes and anthropic activities13. In addition, fungi associated with plants can promote plant growth and development, thereby increasing the availability of nutrients in the soil14. Moreover, plants can increase their ability to absorb water and nutrients15, fight pathogens, decrease the incidence of diseases16,17, fight pests by acting as biocontrol agents18, and increase their resistance to various types of environmental stresses19,20, all of which are caused by beneficial microorganisms associated with the plant. In this sense, the use of filamentous fungi associated with plants is an excellent alternative to address the difficulties related to soybean production, allowing the use of fewer agricultural pesticides and less mineral fertilization, and promoting a lower production cost, with a lower environmental impact without affecting productivity16,21,22,23.

Among the fungi associated with plants, the filamentous fungus Trichoderma harzianum offers numerous advantages and capabilities to plants, including the induction of plant systemic defenses, which can alter plant metabolic pathways, resulting in the activation of various systemic defenses. Activation of plant VOCs: Trichoderma activates the release of plant volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that attract parasitoids and predators of aphids, thereby providing indirect biocontrol. Enhancement of protective enzymes: The fungus enhances the expression of genes encoding protective enzymes against pests, such as moths, contributing to plant defense mechanisms. Oxidative burst: Trichoderma releases VOCs, resulting in an oxidative burst that is effective against aphids and other pests. Promotion of plant growth: Trichoderma acts as a plant biostimulant, promoting plant growth and enhancing tolerance to abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity. Priming and plant memory: The fungus primes plants for enhanced defence responses and contributes to plant memory, which helps plants respond more effectively to future stress. Colonization and communication: Trichoderma colonizes plant roots and acts as an endophyte, establishing beneficial interactions with the plant and modulating its response to environmental challenges. Direct antagonism: Trichoderma directly antagonizes phytopathogens in the rhizosphere, helping protect plants from diseases24.

Another fungus associated with plants used in pest control, particularly in the control of nematodes, is the filamentous fungus P. lilacinum25,26,27. Although P. lilacinum has been used to control nematodes, few studies have shown its high potential for plant growth28,29.

In 2010, transgenic soybean plants were generated using the INTACTA RR2 PRO system, which confers tolerance to glyphosate herbicides and aids in the management of weeds that compete with crops. In addition, this soybean cultivar contains genes that encode B. thuringiensis toxins for the control of the main caterpillars that attack soybeans, namely the soybean caterpillars (Anticarsia gemmatalis), apple borer (Heliothis virescens) and armpit borer (Crocidosema aporema), in addition to the suppression of Elasmo (Elasmopalpus lignosellus) and Helicoverpa (H. zea and H. armigera) caterpillars30. Thus, for the cultivars developed in this system, the cry1Ac gene of B. thuringiensis was added to the inserted genetic modification of the cp4 gene, which is responsible for conferring resistance to glyphosate and one of those responsible for the production of protein crystals with recognized insecticidal action for the cultivar, also commonly called Bt toxin31. Although this variety provides several benefits for soybean production, few studies have investigated the growth-promoting effects of the fungi T. harzianum and P. lilacinum and the influence of these fungi on the modulation of the endophytic microbiome of the roots and leaves of soybean plants using the INTACTA RR2 PRO system.

Objective

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the potential of T. harzianum and P. lilacinum to promote the growth of the soybean cultivar INTACT RR PRO and the effects of these fungi on the endophytic microbiome of the roots and leaves of soybean plants.

Materials and methods

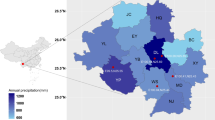

Experiment under field conditions

The experiment was conducted in the research area of the Teaching Research and Extension Farm (FEPE) of the Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Campus de Jaboticabal-SP, located on Prof. Paulo Donato Castellane Road, in the municipality of Jaboticabal, SP, Brazil, at an average altitude of 575 m above sea level. The relief is characterized as gently undulating, and its geographical location is 21° 15′ 22″ S and 48° 18′ 58″ W. The climate is defined as tropical with dry winters and is classified as Aw according to the International System of Koppen Classification. The average annual rainfall was 1425 mm, with a concentration of rainfall in the summer. The soil was Eutrophic Red.

Sowing was performed on December 5, 2023, and plants were harvested on March 19, 2024. Soil was prepared using no-tillage. The soybean cultivar used was INTACTA RR2 PRO (Embrapa Company), which belongs to the semi-early maturation group (6.7 North American classification) and has an indeterminate growth habit. For fertilization, 350 kg ha−1 of the formula 00–20–20 was used in the sowing furrow.

Experimental design

The experiment was conducted in a randomized block design with the following treatments: T1, control (without the application of microorganisms); T2, T. harzianum; T3, P. lilacinum; T4, T. harzianum + P. lilacinum. Each treatment was replicated in four plots with 30 m2 each one. Microorganisms were applied to the foliage with the aid of a coastal pump when the soybean plants were in the V4 phenological stage. The dose of the applied fungi was 300 mL ha−1 at a concentration of 1 × 109 CFU mL−1. The spacing between rows was 0.5 m, and the number of plants was approximately 3000 plants/treatment. The treatment T4 received 300 mL ha−1 of each fungus.

Microorganisms

The fungi T. harzianum and P. lilacinum belong to the collection of the Laboratory of Soil Microbiology, and these strains were collected, isolated, and identified by Dr. Noemi Carla Baron Consentino during her doctoral program in 2020. These strains were isolated from the soil of a rural property of Taquaritinga, São Paulo, Brazil29. The strains were cultured in potato dextrose broth for 14 days at 28 °C. After the incubation period, the concentration was evaluated using the serial dilution method and standardized to 1 × 109 CFU mL−1.

Sample collection for shoot dry matter assessment

During the flowering period of the soybean plants, three plants per replicate were collected and two leaves per plant were separated, totalling six leaves per replicate. Leaves were dried in a forced ventilation oven for 72–96 h at 65 °C and then weighed on a semianalytical scale to measure the shoot dry matter (SDM).

Determination of leaf phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations

After drying, leaves were ground in a mill. The dried and ground samples (5.0 g) were weighed and transferred to 50 mL digestion tubes. The tubes were placed in a digestion block and heated at 80 °C for 20 min, after which the temperature was adjusted to 160 °C and 5 mL of HNO3 was added to each tube. At the end of digestion, the tubes were carefully removed from the block. When most of the HNO3 had evaporated, the solution became clear. The tubes were then removed from the block to cool, and then, 1.3 mL of concentrated HClO4 was added. The tubes were placed back in the digester block and the temperature was increased to 210 °C. The digestion was complete when the solution became colorless, and dense white vapors of HClO4 and H2O formed above the dissolved material inside the tube. The tubes were then cooled again, and the samples were diluted with H2O to 25 mL in a snap-cap glass32.

For phosphorus measurements, 1 mL of the sample was pipetted and transferred to a test tube, and 4 mL of water and 2 mL of the reagent (a mixture of equal parts of 5% ammonium molybdate and 0.25% vanadate) were added. The tube was left to rest for 15 min, and the absorbance was measured at 420 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. For the nitrogen measurements, 1 mL of the sample was pipetted and transferred to a Kjeldahl distiller. An Erlenmeyer flask containing 25 mL of 2% H3BO3 was connected to the distiller tip and 10 mL of 40% NaOH was added. The steam tap was opened, and distillation was carried out until 50 mL of solution was complete, where it was observed that the color of the H3BO3 solution changed from wine to green. The titration with the 0.01 M HCl solution was carried out, and the end point of the titration was given when the initial burgundy color returned. The volume spent on the titration was multiplied by 1.4 to transform the unit to (g kg−1)33.

Sample collection for metagenomic analysis

For the metagenomic analysis, five plants were collected from each replicate (pot). Each treatment consisted of four replicates. Five plants were selected from each replicate and three leaves and roots were collected from each plant. A total of 15 leaves and five roots were obtained from each replicate. DNA from leaves and roots was extracted and mixed, resulting in a composite DNA sample for each replicate. Leaf collection was performed manually using surgical gloves, and the leaves were immediately deposited in sterilized plastic containers. Root collection was performed with the aid of a hoe, and the rhizosphere soil was removed manually using gloves and a brush. The roots and leaves were subsequently placed in a 50 mL conical tube containing 35 mL of phosphate buffer with 0.02% surfactant (Tween 20). The tubes were vortexed for 2 min to separate the root system from the remaining rhizosphere. Then, using sterilized forceps, the roots and leaves were placed on paper towels and transferred to centrifuge tubes (50 mL). Superficial sterilization of roots and leaves was performed as previously described34, with some modifications. Plant tissues were maintained in 100% ethanol for 3 min, followed by 2% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, and 70% ethanol for 3 min. The disinfected roots and leaves were washed thrice with sterile distilled water, and the last wash was inoculated onto nutrient agar plates to validate the effectiveness of the superficial sterilization procedure.

Yield

To assess the productivity, each experimental plot was harvested separately using a plot harvester (John Deere). The seeds were cleaned, dried to a moisture content of 13%, and then weighed. The average productivity of each treatment was calculated from the average productivity of the plots and estimated to be kg ha−1.

Statistical analysis

The SDM, N, and P content and yield data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the F test using the program AgroEstat35. When the data were significant, the means were compared using the Scott–Knott test at 5% probability.

DNA extraction from the roots and leaves of soybean plants

The sterilized roots and leaves were macerated using a sterile mortar and pestle with liquid nitrogen. A PowerMax soil DNA extraction kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to extract genomic DNA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of the extracted DNA was determined by fluorometry (Qubit™ 3.0, Invitrogen), and the purity was estimated by calculating the A260/A280 ratio via spectrophotometry (NanoDrop™ 1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)36. To evaluate the eukaryotic community, the ITS region was amplified using primers ITS3 (5′-GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′). For both amplicon sets, three forward primers were used. These primers were modified by adding degenerate nucleotides (Ns) to the 5′ region to increase the diversity of target sequences37. PCR was performed for 30 cycles using the HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit (Qiagen) under the following conditions: 94 °C for 3 min; 28 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 5 min. PNA clamp sequences (PNA Bio) were added to block amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from the ribosomes and mitochondria. The amplification products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel to determine the success of amplification and relative intensity of the bands. The 16S rRNA and ITS amplicons were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform. Raw data were obtained from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under BioProject PRJNA1123227 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1123227). All relevant descriptive metadata are provided in each associated biosample."

Data processing

The initial evaluation of the quality of the sequencing data was performed using FastQC software (version 0.11.9)38. For a more in-depth analysis, the USEARCH (version 11.0.667) was used39. The “fastx_info” and “fastq_eestats2” functions were used to examine quality distribution, sequence length, and expected errors. The “search_oligodb’ function of the same software was used to identify the presence and location of the primers 341F (V3–V4 of 16S rRNA) or ITS3 and ITS4 (ITS region). Next, adjacent primers and barcodes were removed from both datasets using Atropos (version 1.1.31)40. To ensure data quality, Fastp (version 0.23.2)41 was used to remove sequences with an average Phred quality lower than Q25 using the parameter "average_qual 25.” Using the "paired-end" sequencing approach, the sequences were merged using PEAR (version 0.9.11)42, with an overlap criterion of at least 10 base pairs (min-overlap 10). The merged sequences of both datasets were processed using the DADA2 pipeline43. The dada2 package (version 1.22.0) was used in R statistical software (version 4.1.2)44. The procedure began with filtering and truncation of the readings by the "filterAndTrim" function, adopting an expected error limit of 2 (“maxEE = 2”). Error probabilities were subsequently estimated based on the basis of the "learnErrors" function. On the basis of this error model, the sequences were corrected via the "dada" function, resulting in the identification of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). These ASVs were analyzed for the removal of possible chimeric sequences via the "removeBimeraDenovo" function. For taxonomic classification of 16S rRNA, ASVs were compared with the SILVA database (version 138.1)45, allowing taxonomic identification down to the level of bacteria or archaea. The UNITE database (version 25.07.2023; https://unite.ut.ee/) was used for eukaryotic ASVs (ITS). Unclassified ASVs according to their respective taxonomic kingdoms or those identified as potential contaminants, including chloroplast and mitochondrial sequences, were excluded from the analysis. The counts and taxonomic annotations of the ASVs were exported in the "phyloseq" format (R package "phyloseq" phyloseq version 1.38.0)46. The phyloseq data were then transformed into compositional data via the function "phyloseq_standardize_otu_abundance" of the R package "metagMisc" (version 0.04)47 for microbiome analyses.

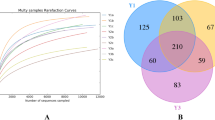

Descriptive and statistical analysis of the bacterial microbiome

The efficiency of the sampling was evaluated via rarefaction curves via "amp_rarecurve" analysis via the R package "ampvis2" (version 2.7.17)48. The samples were then subjected to rarefaction on the basis of the lowest number of sequences found in a library (n = 346,844), and the analyses were conducted using the tables resulting from this rarefaction. Alpha diversity was quantified by examining both species richness (observed and estimated using the Chao1 index) and diversity (Shannon and Gini Simpson indices) via the "alpha" function of the R package "microbiome" (version 1.16.0)49. For comparative analysis of the means, ANOVA was applied, establishing a confidence interval of 95% (p < 0.05). Complementary statistical analyses, including post-hoc multiple comparisons between treatments, were performed with the "emmeans" function (R package "emmeans"; version 1.8.9)50, adjusting the p values using the false discovery rate (FDR) method. Beta diversity analysis was performed by calculating the Bray‒Curtis dissimilarity between the samples via the "distance" function of the "phyloseq" R package. To determine whether there were significant differences between treatments, PERMANOVA was used, with the "adonis" function of the "vegan" vegan’ R package (version 2.6.2)51. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. To interpret the multidimensional distances, a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed, and the results were visualized in subsequent graphs. The identification of differentially abundant taxa among the treatments was performed using DESeq2 methodology (package R version 1.34.0)52. A negative binomial model was used to compare the means using the Wald test (adjusted p < 0.05). The visualizations of the aforementioned analyses were prepared in R via the "ggplot2" package (version 3.3.6)53. Owing to the limited number of sequences remaining after quality control and removal of plant contaminants, the ITS set was excluded from the statistical analyses. Consequently, only the composition of the residual sequences was visualized.

Structural analysis of the bacterial microbiome

To evaluate the structural characteristics of the bacterial communities in response to different treatments, co-occurrence networks were analyzed at the genus level. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated via the "corr.test" function of the "psych" R package (version 2.2.5)54. Only significant correlations (p value < 0.05) with a minimum Pearson coefficient of ± 0.75 were considered, with a focus on strongly positive or negative relationships. Additionally, to reduce noise and focus on the relevant genera, only those with a mean relative abundance of at least 0.001% in at least one treatment were included. The construction of networks and analysis of their topological properties were performed using the R package "igraph" (version 1.3.4)55. Topological properties included the total number of correlated genera (number of nodes), total number of links (edges), average and maximum degrees, modularity, number of modules, clustering coefficient, and measures of average and centrality between maxima. The main "hubs" were identified by calculating "Kleinberg’s hubbiness score”56, highlighting the taxon with the greatest influence.

Results

Experiment under field conditions

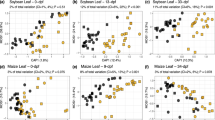

The highest SDM values were found in treatments T2 (T. harzianum), T3 (P. lilacinum) and T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum) compared with those in the control treatment T1, which presented the lowest values (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1).

There was no significant difference (p < 0.05) in nitrogen content between the treatments based on SDM (Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, the phosphorus content was the highest in the T3 treatment, which utilized P. lilacinum (Fig. 2B).

The most abundant phylum was Pseudomonas, and the percentages in the T1 (control), T2 (T. harzianum), T3 (P. lilacinum), and T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum) treatments were 44.93, 29.18, 20.01, and 53.88%, respectively. The second most abundant genus was Bradyrhizobium (31.24%, 33.482%, 44.72%, and 17.43%), and the third most abundant genus was Enterobacter (16.77%, 24.50%, 25.552%, and 24.377%) (Fig. 3). Interestingly, there was a significant difference in the number of species among treatments T1 (control), T2 (T. harzianum), T3 (P. lilacinum), and T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum), with 70, 50, 13, and 29 species, respectively. The most common taxa among the fungi were Sistotrema adnatum, followed by Atractiella rhizophila and Sakaguchia sp. Notably, the fungus-inoculated P. lilacinum and T. harzianum were not isolated (Fig. 4).

Comparative analysis between the treated samples (T2 to T4 treatments) and control samples (T1 treatment) revealed a total of 77 differentially abundant taxa (DA), categorized into two phyla, four classes, five orders, 19 families, and 26 genera. Among these, 58 taxa were predominantly more abundant in the T1 treatment (control), whereas 6, 4, and 9 taxa were more abundant in the T2 (T. harzianum), T3 (P. lilacinum) and T4 (T. harzianum) treatments. + P. lilacinum) The DA taxa at the genus level are shown in (Fig. 5). Notably, with the exception of Kosakonia, all other affected genera had a relative abundance lower than 1%. Multiple comparisons revealed that Oligoflexus, Achromobacter, Shinella and Sphingobacterium were differentially abundant in the T1 treatment (control). Notably, the genus Luteibacter was differentially abundant in the T2 (T. harzianum) and T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum) treatments. However, the greatest variation in relative abundance was recorded for Kosakonia, which was significantly more abundant in T3 (P. lilacinum) (3.6%) than in T1 (control) (0.08%), and Siccibacter, which was more abundant in T1 (control) (0.81%) than in T2 (T. harzianum) (0.003%).

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distances was used to investigate the microbial composition of the samples under different treatments. The results indicate a trend toward a significant separation of the samples as a function of the treatments, although the p value was marginally above the significance threshold (p = 0.051). The dimensionality reduction performed by the PCoA explained 76.07% of the total variability observed in the samples on the first three main axes (Fig. 6). Although considerable variability was observed within the groups and there was some overlap between them, post hoc analyses indicated trends of significant compositional differences between treatments, particularly between T3 (P. lilacinum) and T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum) (p = 0.028), as well as between T1 (control) and T3 (P. lilacinum) (p = 0.058). These results suggested the existence of distinct patterns in the microbial composition associated with each treatment, reflecting the specific influence of each intervention on the microbial community in the leaves of soybean plants.

Beta diversity analysis of bacterial communities via PCoA. Dispersion of the samples on the basis of the Bray‒Curtis distances through the combinations of the axes PCoA 1 and 2 (left) and PCoA 1 and 3 (right). The figure highlights the differences in the microbial composition of soybean leaves between treatments.

Venn diagram analysis (Fig. 7) revealed significant sharing of taxa at the higher taxonomic levels, with 12 phyla and 98 genera identified as common among all treatments. However, the comparison at the ASV level revealed a distinct pattern, with only 59 out of a total of 2207 being shared by all treatments. This result suggests the conservation of the main taxonomic groups among the treatments, whereas the differences in the ASV indicated significant variations in the population composition. With respect to the presence of exclusive taxa, the control treatment (T1) had the greatest number of unique taxa, followed by treatments T3 (P. lilacinum), T2 (T. harzianum) and, T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum), which was consistent at all taxonomic levels analyzed.

Venn diagram of bacterial taxa shared between treatments. Sharing of phyla (A), genera (B) and ASVs (C) among the different treatments. Each set represents the unique and shared diversity of taxonomic categories, providing information on overlaps and exclusivity among treatments. T1 = Control; T2 = T. harzianum; T3 = P. lilacinum; T4 = T. harzianum + P. lilacinum.

The structure of the microbiomes of the samples was inferred from the co-occurrence networks of different treatments. Changes were observed in the relationships between the identified genera (Fig. 8). In this sense, treatment T1 (control) had a greater number of correlated genera ("N. of nodes") and correlations ("N. of edges"). Although this treatment had more than twice the amount of bonding compared with the other treatments, treatments T2 (T. harzianum) and T3 (P. lilacinum) presented a greater number of negative bonds ("negative edges"), with 57 and 71, respectively, compared with only 25 in T1 (control). The characteristics of T1 (control) are mainly due to the presence of a cluster with a large number of correlations, reflecting higher means of connections ("Mean degree") and the average and maximum potential of betweenness/Max. betweenness"). This is further reinforced by the high number of key taxa ("main hubs") found for this treatment. In general, treatments with fungal inoculants resulted in reduced binding, increased negative binding (except for T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum)), and a reduction in the number of key taxa, which differed between the treatments.

Bacterial genera co-occurrence networks by treatment. Cooccurrence networks of the identified genera, based on Pearson's correlation coefficients (r = ± 0.75) and a 95% confidence level (p value < 0.05). Positive connections are highlighted in blue, and negative connections are highlighted in red, while the filled colour of the nodes indicates the phylum to which the genus belongs. Critical nodes for the structure of the network (articulation points) are emphasized with an external contour, emphasizing their importance in the connectivity between submodules of the network. T1 = Control; T2 = T. harzianum; T3 = P. lilacinum; T4 = T. harzianum + P. lilacinum.

The highest mean yield value (p < 0.05) was found for treatment T3 (P. lilacinum) compared to that of treatment T1 (control). The T2 (T. harzianum), T3 (P. lilacinum), and T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum) treatments did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) from each other (Fig. 9).

Correlations among the taxonomic groups revealed that some genera presented significant positive and negative correlations with several plant growth parameters. Specifically, for productivity, Erwinia and Bacillus presented a positive correction, whereas Blautia presented a negative correction (Fig. 10).

Compared to the other treatments, Treatment T3 (P. lilacinum) was the only treatment that promoted increased productivity (Figs. 9 and 11).

The parameters that were significantly influenced by the T3 treatment (P. lilacinum) were the phosphorus concentration in the SDM, productivity, and nitrogen content (Fig. 12).

Discussion

Most studies conducted thus far have demonstrated the capacity of P. lilacinum to exert biological control over a variety of important nematode species57,58,59. However, only a limited number of studies have revealed that this fungus can also promote plant growth. In the present study, all treatments resulted in an increase in SDM compared to the control treatment, which did not receive fungal inoculation (Fig. 1A). Other studies have shown that P. lilacinum can enhance SDM. Alves et al.60 confirmed this effect in common beans, and Haque et al.27 have demonstrated this effect in rice. These studies have proposed that the ability to promote an increase in SDM is due to its ability to produce phytohormones that promote the development of roots and shoots, increase soil exploitation and photosynthetic efficiency, and contribute to increased resistance to abiotic stresses and plant growth61,62. In the present study, there was no variation in nitrogen content among the different treatments (Fig. 2A). In contrast, T3 had the highest phosphorus content (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, this treatment was inoculated with P. lilacinum only, and another study showed that this strain promoted the growth of maize, common bean, and soybean plants as it increased the average levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in the plants29. These findings suggest that P. lilacinum enhances the ability of plants to absorb nutrients from the soil, and can be used for sustainable food production.

According to the taxonomic profile, the T3 treatment (P. lilacinum) increased the prevalence of Bradyrhizobium and the bacterium Kosakonia cowanii (Fig. 5). Interestingly, Bradyrhizobium was a common taxon in treatments T2 (T. harzianum) and T4 (T. harzianum + P. lilacinum), but in treatment T3 (P. lilacinum), Bradyrhizobium was a binding taxon linking two distinct networks (Fig. 8). Compared to the control treatment, treatment T3 (P. lilacinum) was the only treatment that promoted increased soybean productivity under field conditions (Figs. 3 and 9). Further research is necessary to confirm whether the application of P. lilacinum increases the abundance of Bradyrhizobium in soybean plants. In addition, there were positive and significant correlations for yield, SDM, average nitrogen, and phosphorus contents with increasing abundance of Erwinia bacterium, average nitrogen content and yield with increased abundance of Bacillus, and mean nitrogen content with increased abundance of Sphingomonas. The genus Sphingomonas includes bacteria that produce phytohormones and VOCs, and some studies have shown that Sphingomonas can promote plant growth63,64.

The genus Erwinia includes several bacterial species that are classified as plant pathogens. However, this genus also harbors species that have been reported to promote plant growth. A study revealed a new strain of bacteria, A4, from almond tree leaves that may promote plant growth by increasing access to nutrients and producing a stress-reducing compound called spermidine. This bacterium has been reported to have the potential for use in various crops to improve productivity and sustainability in agriculture. The bacterium Erwinia A4 was also shown to successfully colonize the A. thaliana model plant, spreading from the roots to aerial parts, such as leaves and flowers, indicating its ability to live inside the plants and potentially benefit them by promoting plant growth. Genome analysis of the bacterium Erwinia A4 revealed unique genes that might contribute to its ability to promote plant growth, including those involved in the synthesis of spermidine, a compound known to help plants cope with stress. Experiments have shown that plants treated with A4 have 30% greater fresh mass than untreated plants, suggesting that A4 significantly increases plant growth65.

In general, the treatments with the fungi T. harzianum and P. lilacinum resulted in a reduction in the number of co-inoculated taxa, an increase in the number of negatively correlated taxa (except for T4), and a reduction in the number of key taxa, which in turn differed between the treatments. These observations suggest that treatments differentially influence the structure and dynamics of microbial communities, altering the patterns of co-occurrence and relative importance of certain taxa within the networks. Studies have shown varying results regarding the effects of Trichoderma spp. and P. lilacinum on the microbiome. Zhang et al.66 evaluated the effects of several species of Trichoderma sp. on the microbiome of ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) and verified that when Trichoderma sp. was introduced into the soil, the variety of fungi decreased. This could be because Trichoderma sp. compete with or inhibit the growth of other fungi, especially harmful fungi. In contrast, Trichoderma spp. increased the abundance of various bacteria in the soil. More diverse bacteria can improve the soil health and support plant growth. However, Zhang et al.67 evaluated the effect of P. lilacinum on tobacco and verified that the fungal communities in the soil where P. lilacinum was applied presented greater diversity than the bacterial communities, suggesting that the presence of a greater number of distinct fungal species, as opposed to bacteria, diminished microbial diversity. These findings suggest that the manner and extent of P. lilacinum application can affect the various microorganisms present in the soil. These results, including those of the present study, suggest the existence of distinct patterns in the microbial composition associated with each treatment, reflecting the specific influence of each intervention on the microbial community of soybean plants.

Plant growth is influenced by numerous factors, and it is intriguing to consider how these factors interact with one another. The plant microbiome is one of the key factors affecting plant growth. The plant microbiome is comprised of a diverse array of microorganisms. These microorganisms interact with plants in various ways, commensally, beneficially, or pathogenically, and engage in competitive or synergistic interactions. Harnessing the plant microbiome to promote plant growth offers significant potential as an environmentally friendly approach to meet the increasing food demands of the world's growing population and to mitigate the environmental and societal challenges of large-scale food production68.

Thus, the plant microbiome can be used as an effective strategy for increasing plant growth. However, altering the microbiome to promote plant growth remains challenging. Despite numerous studies highlighting the disease suppression and plant growth-promoting abilities of the rhizosphere microbiome, the field application of these findings remains limited. Consequently, further research into the dynamic interactions between crop plants, rhizosphere microbiome, and environment is essential for effectively utilizing the microbiome to increase crop yield and quality12,69.

The results of this study suggest that microbial inoculation, which increases the negative co-occurrence of certain taxa, can promote plant growth. Wang et al.70 demonstrated that, while antagonistic interactions among diverse microbial strains can negatively affect plant growth, the overall effect of increased microbial diversity is beneficial for plant biomass accumulation. This suggests that the positive effects of microbial diversity outweigh those of the negative interactions between specific taxa. Similarly, Hang et al.71 highlighted the synergistic interactions between Trichoderma and resident Aspergillus spp., which enhanced plant growth despite the potential competition between the two fungal taxa. Zhao et al.72 also supported the notion that inoculation with specific microbial strains can shift community structures in a way that enriches functions related to plant growth promotion, even if it involves antagonism against specific taxa present in the plant microbiome.

As previously mentioned, compared to the control treatment, T3 treatment (P. lilacinum) promoted an increase in soybean yield. Yield is influenced by several factors, and in a complex way, which may have been due to the various changes promoted by the application of the fungus P. lilacinum to soybean plants, such as the aforementioned changes in the composition of the plant microbiome and the increase in phosphorus levels in leaves.

Conclusion

The results of the present study show that it is possible to significantly increase the productivity of the transgenic soybean INTACTA RR PRO with the application of the fungus P. lilacinum. This increase in productivity may have occurred due to a set of several factors that were influenced by the application of the fungus P. lilacinum, such as the increase in the phosphorus content in the SDM; the increase of the taxon Erwinia, Bacillus and Sphingomonas in the plant tissues; their positive and significant correlations with the productivity and the average phosphorus and nitrogen contents in the SDM; and the promotion of the genus Bradyrhizobium as a linking taxon of other taxon networks. The application of P. lilacinum could prove to be a promising approach to increasing the productivity of soybean INTACT RR2 PRO for sustainable production, as it has demonstrated the ability to optimize the efficiency of the plant in absorbing nutrients from the soil and modulating the plant microbiome, resulting in positive effects on the plant.

Data availability

The raw data can be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioProject PRJNA1123227. Software (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1123227). All relevant descriptive metadata were provided for each associated biosample.

References

Liu, S., Zhang, M., Feng, F. & Tian, Z. Toward a “green revolution” for soybean. Mol. Plant. 13, 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.03.002 (2020).

Hamza, M. et al. Global impact of soybean production: A review. Asian J. Biochem. Genet. Mol. Biol. 16, 12–20 (2024).

Karges, K. et al. Agro-economic prospects for expanding soybean production beyond its current northerly limit in Europe. Eur. J. Agron. 133, 126415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2021.126415 (2022).

Roth, M. G. et al. Integrated management of important soybean pathogens of the United States in changing climate. J. Integr. Pest. Manag. 11, 17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmaa013 (2021).

Pozebon, H. et al. Arthropod invasions versus soybean production in Brazil: A review. J. Econ. Entomol. 113, 1591–1608. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaa108 (2020).

Singh, A. Soil salinization management for sustainable development: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 277, 111383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111383 (2021).

Nendel, C. et al. Future area expansion outweighs increasing drought risk for soybean in Europe. Glob. Chang Biol. 29, 1340–1358 (2023).

Adeyemi, N. O. et al. Alleviation of heavy metal stress by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in Glycine max (L.) grown in copper, lead and zinc contaminated soils. Rhizosphere 18, 100325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100325 (2021).

Nakagawa, A. C. S. et al. High temperature during soybean seed development differentially alters lipid and protein metabolism. Plant Prod. Sci. 23, 504–512 (2020).

Jia, F., Peng, S., Green, J., Koh, L. & Chen, X. Soybean supply chain management and sustainability: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Product. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120254 (2020).

Trivedi, P., Leach, J. E., Tringe, S. G., Sa, T. & Singh, B. K. Plant–microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0412-1 (2020).

Hassani, M. A. et al. Microbiome network connectivity and composition linked to disease resistance in strawberry plants. Phytobiomes J. https://doi.org/10.1094/pbiomes-10-22-0069-r (2023).

Ancheeva, E., Daletos, G. & Proksch, P. Bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi. Curr. Med. Chem. 27, 1836–1854 (2019).

Lekberg, Y. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization consistently favor pathogenic over mutualistic fungi in grassland soils. Nat. Commun. 12, 3484. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23605-y (2021).

Zanne, A. E. et al. Fungal functional ecology: Bringing a trait-based approach to plant-associated fungi. Biol. Rev. 95, 409–433 (2020).

Sallam, N., Ali, E. F., Seleim, M. A. A. & Khalil Bagy, H. M. M. Endophytic fungi associated with soybean plants and their antagonistic activity against Rhizoctonia solani. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest. Control. 31, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-021-00402-9 (2021).

El-Baky, N. A. & Amara, A. A. A. F. Recent approaches towards control of fungal diseases in plants: An updated review. J. Fungi. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7110900 (2021).

Lopes, R. B. et al. Efficacy of an oil-based formulation combining Metarhizium rileyi and nucleopolyhedroviruses against lepidopteran pests of soybean. J. Appl. Entomol. 144, 678–689 (2020).

Sodhi, G. K. & Saxena, S. Plant growth promotion and abiotic stress mitigation in rice using endophytic fungi: Advances made in the last decade. Environ. Exp. Bot. 209, 105312 (2023).

Ahammed, G. J., Shamsy, R., Liu, A. & Chen, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-induced tolerance to chromium stress in plants. Environ. Pollut. 327, 121597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121597 (2023).

Zhang, T., Yu, L., Shao, Y. & Wang, J. Root and hyphal interactions influence N transfer by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soybean/maize intercropping systems. Fungal. Ecol. 64, 101240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2023.101240 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. The relative contribution of indigenous and introduced arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia to plant nutrient acquisition in soybean/maize intercropping in unsterilized soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 168, 104124 (2021).

Messa, V. R., Torres da Costa, A. C., Kuhn, O. J. & Stroze, C. T. Nematophagous and endomycorrhizal fungi in the control of Meloidogyne incognita in soybean. Rhizosphere 15, 100222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2020.100222 (2020).

Woo, S. L., Hermosa, R., Lorito, M. & Monte, E. Trichoderma: A multipurpose, plant-beneficial microorganism for eco-sustainable agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00819-5 (2023).

Zhan, J. et al. Efficacy of a chitin-based water-soluble derivative in inducing Purpureocillium lilacinum against nematode disease (Meloidogyne incognita). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22136870 (2021).

Lan, X., Zhang, J., Zong, Z., Ma, Q. & Wang, Y. Evaluation of the biocontrol potential of Purpureocillium lilacinum QLP12 against Verticillium dahliae in eggplant. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 4101357. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4101357 (2017).

Haque, Z., Khan, M. R. & Ahamad, F. Relative antagonistic potential of some rhizosphere biocontrol agents for the management of rice root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne graminicola. Biol. Control 126, 109–116 (2018).

Baron, N. C., Rigobelo, E. C. & Zied, D. C. Filamentous fungi in biological control: Current status and future perspectives. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 79, 307–315. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-58392019000200307 (2019).

Baron, N. C., de Souza Pollo, A. & Rigobelo, E. C. Purpureocillium lilacinum and Metarhizium marquandii as plant growth-promoting fungi. PeerJ. 2020, e9005. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9005 (2020).

Bernardi, O. et al. Low susceptibility of Spodoptera cosmioides, Spodoptera eridania and Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to genetically-modified soybean expressing Cry1Ac protein. Crop Protect. 58, 33–40 (2014).

Yu, S. et al. Transcriptional analysis of cotton bollworm strains with different genetic mechanisms of resistance and their response to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin. Toxins (Basel) 14, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14060366 (2023).

Nelson, D. W. & Sommers, L. E. Determination of total nitrogen in plant material. Agron. J. 65, 109–112 (1973).

Paauw, V. F. An effective water extraction method for the determination of plant-available soil phosphorus. Plant Soil 1, 467–480 (1971).

Cao, L., Qiu, Z., You, J., Tan, H. & Zhou, S. Isolation and characterization of endophytic Streptomycete antagonists of Fusarium wilt pathogen from surface-sterilized banana roots. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 247, 147–152 (2005).

Barbosa, J. C. & Maldonado, W. J. AgroEstat: Sistema para análises estatísticas de ensaios agronômicos Vol. 1, 1–396 (Multipress, 2015).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 6, 1621–1624 (2012).

De Souza, R. S. C. et al. Unlocking the bacterial and fungal communities assemblages of sugarcane microbiome. Sci. Rep. 6, 28774. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28774 (2016).

Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Babraham Bioinform. 1, 1–15 (2010).

Edgar, R. Usearch. Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. (LBNL) (2010).

Didion, J. P., Martin, M. & Collins, F. S. Atropos: Specific, sensitive, and speedy trimming of sequencing reads. PeerJ 5, e3720. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3720 (2017).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. in Bioinformatics vol. 34 i884–i890 (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Zhang, J., Kobert, K., Flouri, T. & Stamatakis, A. PEAR: A fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 30, 614–620 (2014).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2012).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8, e61217. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061217 (2013).

Mikryukov, V. metagMisc. Miscellaneous Functions for Metagenomic Analysis (2022).

Andersen, K., Kirkegaard, R., Karst, S. & Albertsen, M. ampvis2: An R package to analyse and visualise 16S rRNA amplicon data. bioRxiv (2004).

Lahti, L. & Shetty, S. Microbiome R package. (2012).

Lenth, R. V. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=emmeans (2023).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2019).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Kassambara, A. ggpubr: “ggplot2” Based Publication Ready Plots. https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=ggpubr (2020).

Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (2022).

Csardi, G. The Igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221995787 (2005).

Kleinberg, J. M. Hubs, Authorities, and Communities. (2000).

Luangsa-Ard, J. et al. Purpureocillium, a new genus for the medically important Paecilomyces lilacinus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 321, 141–149 (2011).

Goffré, D. & Folgarait, P. J. Purpureocillium lilacinum, potential agent for biological control of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex lundii. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 130, 107–115 (2015).

Khan, A., Williams, K. L. & Nevalainen, H. K. M. Infection of plant-parasitic nematodes by Paecilomyces lilacinus and Monacrosporium lysipagum. BioControl. 51, 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-005-4242-x (2006).

Alves, G. S. et al. Fungal endophytes inoculation improves soil nutrient availability, arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization and common bean growth. Rhizosphere 18, 100330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100330 (2021).

Ullah, S., Bano, A., Ullah, A., Shahid, M. A. & Khan, N. A comparative study of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and sowing methods on nutrient availability in wheat and rhizosphere soil under salinity stress. Rhizosphere 23, 100571 (2022).

Morrison, E. N. et al. Detection of phytohormones in temperate forest fungi predicts consistent abscisic acid production and a common pathway for cytokinin biosynthesis. Mycologia 107, 245–257 (2015).

Luo, Y. et al. Complete genome sequence of Sphingomonas sp. Cra20, a drought resistant and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Genomics 112, 3648–3657 (2020).

Khan, A. L. et al. Bacterial endophyte Sphingomonas sp. LK11 produces gibberellins and IAA and promotes tomato plant growth. J. Microbiol. 52, 689–695 (2014).

Saldierna Guzmán, J. P., Reyes-Prieto, M. & Hart, S. C. Characterization of Erwinia gerundensis A4, an almond-derived plant growth-promoting endophyte. Front. Microbiol. 12, 687971. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.687971 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Trichoderma spp. promotes ginseng biomass by influencing the soil microbial community.. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1283492. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1283492 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Effect of Purpureocillium lilacinum on inter-root soil microbial community and metabolism of tobacco. Ann. Microbiol. 73, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13213-023-01734-7 (2023).

Sarpong, C. K. et al. Improvement of plant microbiome using inoculants for agricultural production: A sustainable approach for reducing fertilizer application. Can. J. Soil Sci. 101, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjss-2019-0146 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Harnessing the plant microbiome to promote the growth of agricultural crops. Microbiol. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2020.126690 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Richness and antagonistic effects co-affect plant growth promotion by synthetic microbial consortia. Appl. Soil Ecol. 170, 104300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104300 (2022).

Hang, X. et al. Trichoderma-amended biofertilizer stimulates soil resident Aspergillus population for joint plant growth promotion. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 8, (2022).

Zhao, B. et al. Improving suppressive activity of compost on phytopathogenic microbes by inoculation of antagonistic microorganisms for secondary fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 367, 128288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128288 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Fapesp for the financial support. Process number 2021/10821-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have contributted in this study in the same way.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Experimental research and field studies on plants (either cultivated or wild), including the collection of plant material, must comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation

The soybean cultivar is a business cultivar sold across the country, and is registered with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rigobelo, E.C., de Carvalho, L.A.L., Santos, C.H.B. et al. Growth promotion and modulation of the soybean microbiome INTACTA RR PRO with the application of the fungi Trichoderma harzianum and Purpureocillum lilacinum. Sci Rep 14, 21004 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71565-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71565-2