Abstract

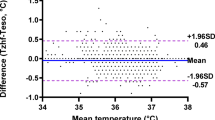

Maintaining patients’ temperature during surgery is beneficial since hypothermia has been linked with perioperative complications. Laparoscopic surgery involves the insufflation of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the peritoneal cavity and has become the standard in many surgical indications since it is associated with better and faster recovery. However, the use of cold and dry CO2 insufflation can lead to perioperative hypothermia. We aimed to assess the difference between intraperitoneal and core temperatures during laparoscopic surgery and evaluate the influence of duration and CO2 insufflation volume by fitting a mixed generalized additive model. In this prospective observational single-center cohort trial, we included patients aged over 17 with American Society of Anesthesiology risk scores I to III undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Anesthesia, ventilation, and analgesia followed standard protocols, while patients received active warming using blankets and warmed fluids. Temperature data, CO2 ventilation parameters, and intraabdominal pressure were collected. We recruited 51 patients. The core temperature was maintained above 36 °C and progressively raised toward 37 °C as pneumoperitoneum time passed. In contrast, the intraperitoneal temperature decreased, thus creating a widening difference from 0.4 [25th–75th percentile: 0.2–0.8] °C at the beginning to 2.3 [2.1–2.3] °C after 240 min. Pneumoperitoneum duration and CO2 insufflation volume significantly increased this temperature difference (P < 0.001 for both parameters). Core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference increased linearly by 0.01 T °C per minute of pneumoperitoneum time up to 120 min and then 0.05 T °C per minute. Each insufflated liter per unit of time, i.e. every 10 min, increased the temperature difference by approximately 0.009 T °C. Our findings highlight the impact of pneumoperitoneum duration and CO2 insufflation volume on the difference between core and intraperitoneal temperatures. Implementing adequate external warming during laparoscopic surgery effectively maintains core temperature despite the use of dry and unwarmed CO2 gases, but peritoneal hypothermia remains a concern, suggesting the importance of further research into regional effects.

Trial registration: Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT04294758.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery is performed by insufflating carbon dioxide (CO2) into the peritoneal cavity to obtain an adequate view during surgery. Typically, this CO2 is dry and not heated, which can lead to a drop in the patient's body temperature. This is concerning because general anesthesia already affects temperature regulation1,2,3,4,5. Perioperative hypothermia has been linked to increased postoperative cardiovascular complications6, increased perioperative bleeding7, and increased surgical wound infection rate8. The detrimental effect of hypothermia has been associated with vasoconstriction, resulting in reduced tissue oxygen transport and inhibition of tissue-dependent cellular functions9. Recent studies questioned the effect of patient warming on postoperative pain and major cardiac events10,11 but still confirmed the association between hypothermia and increased wound infections and blood transfusion need12.

The effects of insufflation gas heating on core temperature have been studied previously, although with inconclusive results, due at least in part to the heterogeneity of experimental design and the bias control strategy implemented in the studies performed13,14,15, For instance, many of these studies did not include in the design any external measure of maintenance of normothermia, such as a fluid warmer or thermal blanket, which can mitigate the hypothermic effect of the cold insufflation by eliminating the main mechanism of temperature loss by convection to the environment, while others found a significant effect if gas humidification was administered along with heating compared to dry and cold insufflation16.

To our knowledge, there isn't much information about measuring the temperature inside the abdomen during cold gas insufflation despite its possible effects on the body's systems14,17,18. One recent study studied the correlation between intraperitoneal and core temperature at different time points. Still, it did not assess data longitudinally nor the effect of the insufflated gas and reported data only on the first 60 min of insufflation19.

We aim to assess the difference between intraperitoneal and core temperature along pneumoperitoneum insufflation and estimate the effect of time and the amount of CO2 insufflated on such difference in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery.

Methods

Study design

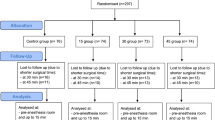

This was an investigator-initiated, single-center, prospective observational cohort trial conducted at La Fe University Hospital. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the la Fe hospital approved the study protocol with the code TEMP-19 on January 29, 2020. The study adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and Spanish biomedical research regulations (Supplementary material). All participants provided written informed consent before joining the trial, and the study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov under the identifier NCT04294758. We included patients over 17 years old scheduled for laparoscopic surgery with the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) risk scores ranging from I to III. Patients with cognitive impairment, pregnant individuals, thyroid disorders, peripheral neuropathies and breastfeeding patients were excluded.

Setting

Anesthesia was induced with propofol, fentanyl, rocuronium, and lidocaine and maintained with total intravenous perfusion of propofol and rocuronium without a heat and moisture exchange (HME) filter. Mechanical ventilation was performed with a fresh gas flow (FGF) of no more than 2 L∙min−1 and an HME filter. Analgesia was administered intravenously or through an epidural catheter, depending on the surgical procedure. Pneumoperitoneum was established using the CO2 supply from the hospital's centralized gas pipeline, which must provide the gas at 20–25 °C and < 5% relative humidity. We tested the gas delivery system used in all surgeries by placing a temperature sensor inside a trocar after the center’s standard 3 m insufflation set (Extrudan Asp, Slagenrup, Denmark) without connecting it to any patient. We found the temperature remained at 22.6 °C. The surgical team's standard procedure was carried out using the center’s standard insufflator (Thermoflator, Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) through the aforementioned insufflation kit connected to a 12 mm umbilical trocar (Hasson type, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland or Kii balloon tip, Applied Medical, Santa Rita, California). Core temperature was monitored in the esophagus with a YSI-400 thermistor reusable probe (General Electric, Boston, Massachusetts, USA) introduced in the thoracic portion of the organ advancing 20 cm from the oral entry, while the intraperitoneal temperature was monitored with a sterile disposable one (Medlinknet, Shenzen, China) through one of the surgical ports (Fig. 1). The latter was introduced during surgery in one of the unused trocars if there were none available in one of the 12 mm instrument trocars, but never through the one connected to the CO2 insufflation. If a position change was needed for surgical reasons, data collection was resumed at the next 10-min interval after signal stabilization. The tip of the intraperitoneal probe was left hanging into the pneumoperitoneum without touching any tissue. Patients were actively warmed during surgery with an adult upper body blanket (Level 1 convective warmer, Smiths Medical, Minneapolis, Minnesota) and a warm water blanket underneath (Aquatherm 660, Hico Medical Systems Cologne, Germany. The administered fluids were also warmed before infusion (Hotline, Smiths Medical Minneapolis, Minnesota) and administered at a fixed rate of 2 ml∙kg−1 h−1 through a standard infusion line of 2.4 m (L-70 NI, Smiths Medical Minneapolis, Minnesota). All equipment was set to warm up to 38 °C. The operating room temperature was set at the standard hospital value, i.e., 21 °C, and was not changed throughout the study. All surgeries were performed using the center’s standard electrosurgical equipment (Valleylab FT10, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) set up at 40-60W both for monopolar and bipolar circuits.

Intraoperative layout from different surgical interventions. (A) and (B) Appendectomy; (C) Hemicolectomy; (D) Cholecystectomy. The thermometer probe (the blue probe protruding from one of the probes in each panel) is inserted in one of the unused 5 mm (A,B,D) trocars if available or in one of the 12 mm trocars (D).

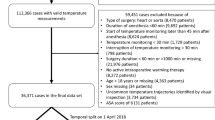

Data collection

We collected demographics and anthropometric data, and from the beginning to the end of pneumoperitoneum insufflation for any reason (end of pneumoperitoneum phase or conversion to open surgery), every 10 min whenever possible, we recorded the following data: core and esophageal temperature, amount of insufflated CO2, ventilatory tidal volume and respiratory rate, end-tidal CO2 and intraabdominal pressure.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was estimated using a Monte Carlo simulation. We originally planned the study to detect a 3ªC difference but finally we carried out the study assuming a core and intraperitoneal temperature difference of 1.5 °C, a standard deviation (SD) of 0.75 and an estimation precision of ± 0.5 °C, we fitted a Bayesian sequential model with 1000 repetitions. We estimated that 50 patients were necessary to achieve the desired degree of estimation precision.

We assessed the core and intraperitoneal temperature difference over time by fitting a mixed generalized additive model (GAM). Gams are a family of models used to assess smooth functional relationships between a set of predictors and a response variable that are particularly suited to analyze longitudinal data with non-linear trends such as our clinical scenario. We chose this type of analysis because GAMs enable the data to establish the trend for the model fit, can model non-constant correlation between repeated measurements, are robust to missing observations, and do not require equally-spaced observation for each subject20. We fitted a GAM introducing a smooth term for time and one for the insufflated CO2 liters to assess their effect on the core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference. We also introduced a random effect for patients to account for interindividual variability.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess whether other characteristics may influence the core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference. The following variables were added to the model in a univariable fashion to see whether they have an effect: age, gender, waist-hip ratio (WHR), body mass index (BMI) and minute ventilation, previous abdominal surgeries, previous laparoscopic surgeries, previous pregnancies, and type of surgery. We applied the Benajmini-Hochberg for multiple comparison correction and false discovery rate control.

Missing data were < 5%, complete cases analysis was carried out. Analyses were carried out using the mgcv package21 for R version 4.2.3 (R development core team, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

We recruited 51 patients from March 2021 to January 2023. Patients’ baseline characteristics and intraoperative data are reported in Table 1. Most patients underwent coloproctologic surgery, and conversion to open surgery was unnecessary. Median [25th–75th percentile] values for BMI and waist WHR were 25.7 [23.2–28.1] and 1.0 [0.9–1.0], respectively. Insufflation pressure was maintained at 12 mmHg throughout the pneumoperitoneum in every case.

Core body temperature was maintained above 36 °C and progressively raised toward 37 °C while intraperitoneal temperature decreased as pneumoperitoneum time passed, thus creating a widening difference from 0.4 [0.2–0.8] °C at the beginning to 2.3 [2.1–2.3] °C after 240 min. CO2 insufflated liters and insufflation flow increased with time. Minute ventilation also increased with time to maintain normocapnia, mainly by incrementing the respiratory rate. Intraabdominal pressure was maintained at 12 mmHg in most patients most of the time (Fig. 2 and Table 2). There was no significant difference in core temperature between emergent and elective surgery (0.4 °C 95%Confidence Interval, CI − 0.03 to 0.8, P = 0.07).

Longitudinal data collection. The insufflation time in minutes is collected on the x-axis. The y-axis shows in each panel respectively: (A) the central (blue) and peritoneal (orange) temperatures; (B) the temperature difference; (C) the amount of insufflated liters each 10-min interval; (D) the cumulative amount of insufflated liters; (E) the insufflation flow; (F) the respiratory tidal volume; (G) the respiratory rate; (H) the minute ventilation volume; (I) the end-tidal carbon dioxide; (J) the intrabdominal pressure. The dots are mean values at each time point; the bars are standard error bars at each time point. The fitted line is a smoothed linear regression fitted with a cubic spline to retain non-linear capabilities. The grey band is the 95% confidence band. The y-axis for (A) and (F–J) is shortened to improve readability. EtCO2.

Both pneumoperitoneum time and insufflated liters significantly increased the difference between core and intraperitoneal temperature (p < 0.001 for both variables, model deviance explained: 73.6%). Results from fitting the mixed GAM are reported in Fig. 3. We show the effect of pneumoperitoneum insufflation time and insufflated liters both as the predicted temperature difference value by each variable value and as the marginal effects, i.e., how much change in temperature difference per unit of value of the fitted variable. Core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference increased linearly by 0.01 T °C per minute of pneumoperitoneum time up to 120 min and then 0.05 T °C per minute. Each insufflated liter per unit of time, i.e., every 10 min, increased the temperature difference by approximately 0.009 T °C. The effect of insufflation reported as the effect of cumulative liters insufflation showed how the core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference increased up to a plateau of approximately 2 °C.

Mixed GAM estimates. Predictions (Left panels) and marginal effects (Right panels) of core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference from the GAM by time elapsed (A and B), by insufflated liters per unit of time elapsed (C and D), by cumulative insufflated liters (E and F). The left panels show the model predictions for the response variable plotted on the Y-axis, i.e. the temperature difference between core and intraperitoneal temperature, based on the values of the predictors plotted on the X-axis. The right panels look at the slopes or gradients of the relationships between each predictor and the response variable, i.e. how the rate of change varies along different values of the predictor. Black lines are the estimates from the model. Grey bands are 95% confidence bands. GAM, Generalized Additive Model.

We found no significant results in the sensitivity analysis of characteristics influencing the core vs. intraperitoneal difference (Table 3).

Discussion

The key findings can be summarized as follows: there is a significant difference between the core body and the intraperitoneal temperature as the former increases due to adequate external warming while the latter decreases during the pneumoperitoneum insufflation. This increase in difference is linked to two factors: (i) the duration of pneumoperitoneum, the longer the pneumoperitoneum lasts, the greater this temperature difference becomes, and (ii) the number of insufflated liters; more insufflated liters also contribute to a larger temperature difference. Also, (iii) the temperature difference rises linearly with the number of insufflated liters. However, its increase is non-linear with the duration of insufflation. Initially, there's a steeper increment during the first 120 min, but it eventually levels off at approximately 2 °C. The sensitivity analysis of potential modifying factors found no significant association between any characteristics and the difference in temperature between the peritoneum and the core.

This study has several strengths. Its methodology was carefully planned and executed, utilizing statistical methods well-suited for handling data with a hierarchical structure, especially when dealing with repeated measures and correlated data over time without relying on individual timepoint hypothesis testing. In addition, we fitted a multivariable model to estimate the effects of both time and insufflated CO2. Also, we gathered granular data by shortening the data collection intervals while extending the follow-up to the entire pneumoperitoneum duration. This method enabled us to quantify the expected temperature changes for specific insufflated gas volumes and elapsed time. We also restricted the FGF during mechanical ventilation since higher FGFs can produce heat loss and bias esophageal temperature measurements22,23.

Our findings on the effect of pneumoperitoneum duration align with previous studies. A recent trial showed a significant difference between core and intraperitoneal temperature after 30 min of laparoscopy. However, mostly shorter surgeries were recruited, data were collected up to 60 min, and time points were analyzed individually, which implies independence of data, whereas temperature measurement is longitudinal, and the correlation between data must be taken into account19. Our study expands the studied population, including longer surgeries, and shows how the difference in temperature keeps increasing. Another investigation on obese patients undergoing gastric bypass showed significant differences in core vs. intraperitoneal temperature in a small subsample of laparoscopic patients where both temperatures were measured24. On the other hand, a small study conducted on patients scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy did not find any difference, probably because the abdominal probe was touching the visceral peritoneum directly25. Interestingly, warming measures were implemented in all these trials, and they observed, like us, how the temperature difference widens as the core temperature is maintained while the abdominal one lowers as the insufflation continues. The number of applied active warming measures is also relevant. In a big study with over 50,000 patients, their core temperature dropped in the first hour of surgery despite using warming blankets26. However, we did not see that drop in our study, partially because we started recording the temperature pair at the beginning of pneumoperitoneum and not after the anesthetic induction. Another reason could be that even though we did not warm patients before surgery, we used multiple warming methods during surgery, which might have attenuated the temperature drop. Recent studies show that using more than one warming method can keep the temperature stable during surgery27.

Despite guidelines recommendations28, the incidence of intraoperative hypothermia is still high and even significantly higher for laparoscopic compared to open approaches for the same surgical indications (71% vs. 63%)29. While the role of measures such as warming blankets and fluid warmers in preventing intraoperative temperature loss is well established, the effect of heating the insufflated CO2 during laparoscopy is still debated. The insufflation of warm and humidified CO2 has been shown to increase the core temperature in open wounds30 and laparoscopic patients28. Also, recent systematic reviews showed slightly higher core temperatures if warmed and humidified gas was administered15,16, and another showed a small benefit if humidification was added to standard heating, although no benefit in clinical outcomes could be found31. Another recent meta-analysis carried out in colorectal surgery found no differences in core temperature between standard and warm-humidified insufflation, although with heterogeneity both in active warming measures and surgical indications32. The marginal effect of warmed insufflation on core temperature probably depends on whether adequate external warming is implemented since it likely has a bigger impact12. Indeed, our results show how core temperature can effectively be maintained if clinical guidelines on normothermia are followed despite relatively long procedures being carried out and high amounts of CO2 being insufflated. Of note, the cited systematic reviews focus on core body temperature, and intraperitoneal temperature measurements are usually not reported.

We found that the amount of CO2 liters insufflated each unit of time during the pneumoperitoneum increased core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference linearly. Our model estimates an increase in temperature difference of 0.45 °C every 50 L each 10 min of pneumoperitoneum. Heat loss is thus related to the rate of flow administered during the pneumoperitoneum. This fact is crucial as frequently high flows are required to evacuate smoke from electrosurgical devices to improve visibility. We also observed that although nonlinearly, the core vs. intraperitoneal temperature difference increased with cumulative insufflated liter. After an initial almost linear increase, our model showed how this effect reaches a plateau around 300L. A straightforward explanation is that the heating loss effect of CO2 insufflation is counterbalanced in our sample by adequate external warming. In other conditions, internal abdominal temperature can reach as low as 27.7 °C during laparoscopic insufflation33. Of note, CO2 is denser than other gases used for insufflation, which affects how it moves heat. It also has a lower specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity. This means it requires less energy to raise its temperature and is less efficient at conducting heat. Thus, our findings may not apply to other gases used in laparoscopic procedures34. Similarly, we derived these estimates for time and insufflated liters under steady-state insufflation at 12 mmHg. Recently, there has been renewed interest in the potential benefit of low insufflation pressure during laparoscopy35. Operating at a lower pressure can probably affect the rate of insufflation. Therefore, our model’s estimation should be assessed at different insufflation pressures.

As we previously pointed out, there is still little evidence of clinical benefits from warming insufflated gas. Our results show how core and intraperitoneal temperatures can diverge considerably and how the peritoneal microenvironment is submitted to regional mild hypothermia. We should shift the focus from systemic to regional effects on the peritoneal microenvironment36. Indeed, there is some evidence that heated CO2 reduced plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) and tumor growth factor β, which are linked to adhesion formation, although the clinical effect of this intraperitoneal hyperthermia remains to be elucidated37,38. Also, a recent randomized clinical trial (RCT) showed how peritoneal damage assessed by electron microscopy increased during surgery in patients who underwent surgery with dry and cold CO2 compared to those who received warm-humidified CO2 insufflation39.

Some limitations must be acknowledged. First, we aimed to describe the effect of cold and dry insufflation without testing any specific hypothesis; therefore, our results should be considered exploratory, and the potential effect of this difference on clinical outcomes such as wound infection or anastomotic leaks should be assessed in properly sized future trials. Indeed, since the descriptive nature of our aim, we did not introduce epidural analgesia in our model since they are strongly correlated with surgery time and thus can create collinearity problems in our model and compromise its explanatory value; therefore, our findings should be further investigated to explore specific scenarios such as type of regional anesthesia or emergency surgery. Moreover, our protocol did not use any prewarming measure since it is not routinely implemented at our center. Also, we tested the temperature at the outlet but did not constantly monitor it, thus some potential fluctuations could not be evaluated. In addition, we used one model of commercial insufflator. However, there is quite a wide range of other insufflators in the market with different capabilities that we cannot test in the present study. The same limitations must be acknowledged for the electrosurgical equipment; since we used a specific equipment, results with other devices must be confirmed. Furthermore, we analyzed potential effects from a series of baseline characteristics, although these findings must be interpreted as exploratory due to the multiple comparisons and the specific focus of our research question that focused on precision rather than differences between groups. Additionally, we did not record the duration between the induction of anesthesia and the start of surgery. However, it's worth noting that the surgical team remained consistent throughout all cases, implying that this time interval can be regarded as relatively constant. Also, our study focused on clinical conditions where patients are actively warmed during surgery following current guidelines40. Therefore, its results in a clinical scenario where no adequate warming measures are implemented should be evaluated (Supplementary Information).

In conclusion, the difference between core and intraperitoneal temperature in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery increases with the pneumoperitoneum duration and the number of insufflated liters. The effect of this regional hypothermia on clinical outcomes should be elucidated in future investigations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sessler, D. I. Perioperative temperature montoring. Anesthesiology. 134, 111–118 (2021).

Simegn, G. D., Bayable, S. D. & Fetene, M. B. Prevention and management of perioperative hypothermia in adult elective surgical patients: A systematic review. Ann. Med. Surg. 72, 103059 (2021).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Comparative effects of warming systems applied to different parts of the body on hypothermia in adults undergoing abdominal surgery: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Anesth. 89, 111190 (2023).

Lenhardt, R. Body temperature regulation and anesthesia. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 157, 635–644 (2018).

Sessler, D. I. Perioperative heat balance. Anesthesiology. 92, 578–596 (2000).

Madrid, E. et al. Active body surface warming systems for preventing complications caused by inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4(4), CD009016 (2016).

Sun, Z. et al. Intraoperative core temperature patterns, transfusion requirement, and hospital duration in patients warmed with forced air. Anesthesiology 122, 276–385 (2015).

Sessler, D. I. Perioperative thermoregulation and heat balance. Lancet 387(10038), 2655–2664 (2016).

Mauermann, W. J. & Nemergut, E. C. The anesthesiologist’s role in the prevention of surgical site infections. Anesthesiology 105, 413–421 (2006).

Feng, Y. et al. Effect of active warming on perioperative cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Anesth. 37, 573–581 (2023).

Sessler, D. I. et al. Aggressive intraoperative warming versus routine thermal management during non-cardiac surgery (PROTECT): A multicentre, parallel group, superiority trial. Lancet. 399(10337), 1799–1808 (2022).

Balki, I. et al. Effect of perioperative active body surface warming systems on analgesic and clinical outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth. Analg. 131, 1430–1443 (2020).

De Csepel, J. & Wilson, E. Heating and humidifying carbon dioxide is indicated. Surg. Endosc. 21, 340–341 (2007).

Davis, S. S. et al. Heating and humidifying of carbon dioxide during pneumoperitoneum is not indicated: A prospective randomized trial. Surg. Endosc. 20, 153–158 (2006).

Dean, M. et al. Warmed, humidified CO2 insufflation benefits intraoperative core temperature during laparoscopic surgery: A meta-analysis. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 10, 128–136 (2017).

Balayssac, D. et al. Warmed and humidified carbon dioxide for abdominal laparoscopic surgery: Meta-analysis of the current literature. Surg. Endosc. 31, 1–12 (2017).

Semm, K., Arp, W. D., Trappe, M. & Kube, D. Schmerzreduzierung nach pelvi/-laparoskopischen Eingriffen durch Einblasen von körperwarmem CO2-Gas (Flow-Therme). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 54, 300–304 (1994).

Slim, K. et al. Effect of CO2 gas warming on pain after laparoscopic surgery A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Surg. Endosc. 13, 1110–1114 (1999).

Groene, P., Gündogar, U., Hofmann-Kiefer, K. & Ladurner, R. Influence of insufflated carbon dioxide on abdominal temperature compared to oesophageal temperature during laparoscopic surgery. Surg. Endosc. 35, 6892–6896 (2021).

Mundo, A. I., Tipton, J. R. & Muldoon, T. J. Generalized additive models to analyze nonlinear trends in biomedical longitudinal data using R: Beyond repeated measures ANOVA and linear mixed models. Stat. Med. 41, 4266–4283 (2022).

Wood, S. N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 73, 3–36 (2010).

Erdling, A. & Johansson, A. Core Temperature-the intraoperative difference between esophageal versus nasopharyngeal temperatures and the impact of prewarming, age, and weight: A randomized clinical trial. AANA J. 83, 99–105 (2015).

Bilgi, M. et al. Comparison of the effects of low-flow and high-flow inhalational anaesthesia with nitrous oxide and desflurane on mucociliary activity and pulmonary function tests. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 28, 279–283 (2011).

Nguyen, N. T. et al. Effect of heated and humidified carbon dioxide gas on core temperature and postoperative pain: A randomized trial. Surg. Endosc. 16, 1050–1054 (2002).

Saad, S., Minor, I., Mohri, T. & Nagelschmidt, M. The clinical impact of warmed insufflation carbon dioxide gas for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 14, 787–790 (2000).

Sun, Z. et al. Intraoperative core temperature patterns, transfusion requirement, and hospital duration in patients warmed with forced air. Anesthesiology. 122, 276–285 (2015).

Wittenborn, J. et al. The effect of warm and humidified gas insufflation in gynecological laparoscopy on maintenance of body temperature: A prospective randomized controlled multi-arm trial. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 306, 753–767 (2022).

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia: The management of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in adults. (2016) http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG65.Last (Accessed 02 Sept. 2023).

Cumin, D., Fogarin, J., Mitchell, S. J. & Windsor, J. A. Perioperative hypothermia in open and laparoscopic colorectal surgery. ANZ J. Surg. 92, 1125–1131 (2022).

Frey, J. M., Janson, M., Svanfeldt, M., Svenarud, P. K. & Van Der Linden, J. A. Local insufflation of warm humidified CO2 increases open wound and core temperature during open colon surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Anesth. Analg. 115, 1204–1211 (2012).

Birch, D. W. et al. Heated insufflation with or without humidification for laparoscopic abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10(10), CD007821 (2016).

Sharma, S. et al. The role of warmed-humidified carbon dioxide insufflation in colorectal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 26(1), 7–21 (2024).

Jacobs, V. R., Morrison, J. E., Mettler, L., Mundhenke, C. & Jonat, W. Measurement of CO2 hypothermia during laparoscopy and pelviscopy: How cold it gets and how to prevent it. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 6, 289–295 (1999).

Galetin, T. & Galetin, A. Influence of gas type, pressure, and temperature in laparoscopy—A systematic review. Ann. Laparosc. Endosc. Surg. 7, 6 (2022).

Reijnders-Boerboom, G. T. J. A. et al. Low intra-abdominal pressure in laparoscopic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 109, 1400–1411 (2023).

Umano, G. R., Delehaye, G., Noviello, C. & Papparella, A. The, “dark side” of pneumoperitoneum and laparoscopy. Minim. Invasive Surg. May. 19, 5564745 (2021).

Lensvelt, M. A., Ivarsson, M. L., Brokelman, W. J. A., Falk, P. & Reijnen, M. M. P. J. Decreased peritoneal expression of active transforming growth factor Beta1 during laparoscopic cholecystectomy with heated carbon dioxide. Arch. Surg. 145, 968–972 (2010).

Brokelman, W. J. A. et al. Peritoneal transforming growth factor beta-1 expression during laparoscopic surgery: A clinical trial. Surg. Endosc. 21, 1537–1541 (2007).

Sampurno, S. et al. Effect of surgical humidification on inflammation and peritoneal trauma in colorectal cancer surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29, 7911–7920 (2022).

Rauch, S. et al. Perioperative hypothermia—a narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18(16), 8749 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of the staff of General Surgery operating rooms at the Hospital Universitario la Fe, Valencia. In particular, we would like to thank Matteo Frasson, Jorge Sancho, Hanna Cholewa from the department of General Surgery.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guido Mazzinari: study design; data collection and analysis; manuscript draft and review; final manuscript approval. Lucas Rovira, Oscar Diaz-Cambronero: study design; manuscript draft and review; final manuscript approval. Maria Vila Montañes, Nuria García Gregorio, Begoña Ayas Montero, Maria Jose Alberola Estellés: data collection; manuscript review; final manuscript approval. Blas Flor, Maria Pilar Argente Navarro: manuscript review; final manuscript approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mazzinari, G., Rovira, L., Vila Montañes, M. et al. Estimation of the difference between peritoneal microenvironment and core body temperature during laparoscopic surgery – a prospective observational study. Sci Rep 14, 20408 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71611-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71611-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Explainable prediction of hypothermia risk in laparoscopic surgery: a retrospective cross-sectional study using machine learning

BMC Surgery (2025)

-

Visualisation and quantification of the effects of surgical humidification on intestinal perfusion and viability in a porcine model

Scientific Reports (2025)