Abstract

A high efficiency simulation method for propagation-based phase-contrast imaging, called directional macro-wavefront (DMWF), is developed with the aim of simulating high-energy phase-contrast imaging. This method takes both Monte Carlo and wave optical propagation into consideration. Traditional wave-optics-based simulation methods for phase-contrast imaging encounter unacceptable computational complexity when high-energy radiation is used. In contrast, this method effectively addresses this issue by using macro-wavefront integration. Several simulation examples using typical parameters of inverse Compton scattering sources are presented to illustrate the excellent energy adaptability and efficiency of the DMWF method. This method provides a more efficient approach for phase-contrast imaging simulations, which will drive the advancement of high-energy phase-contrast imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over more than a century since the discovery of X-rays, X-ray imaging techniques have been widely applied in various fields such as medicine and industry due to the superior penetrability of X-rays. The X-ray imaging technique commonly utilizes the attenuation effect of X-rays in materials, which is positively correlated with the atomic number. However, with regard to low-Z materials such as organic substances, the excessive penetrating power of X-rays often leads to negligible attenuation and low image contrast. The advent of X-ray phase-contrast imaging (PCI) has overcome this problem and makes high-contrast imaging of these low-Z materials possible. The physical basis behind X-ray PCI is the phase shift and the attenuation when they interact with matters, which is determined by the complex refractive index of the material1

where \(\delta \) denotes the real part of the refractive index decrement and is associated with phase shift, and \(\beta \) denotes the absorption coefficient.

Usually, \(\delta \) is approximately \(2-3\) orders of magnitude larger than \(\beta \) in X/soft-\(\gamma \) ray energy region. Therefore, phase contrast imaging techniques hold the promise of achieving a significantly higher contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) compared to attenuation-based imaging. Moreover, phase shift provides information about the electron density of the material. By combining attenuation, phase-shift or even dark-field information, there is a potential for quantitatively reconstructing the composition of a target object2,3,4.

With the development of PCI techniques, they have been considered to be applied for large-sized objects or materials with high atomic numbers in higher X/\(\gamma \)-ray energy region. However, there is a lack of investigations for PCI beyond \({100}\,\hbox {keV}\)5,6,7, as numerous technical challenges need to be addressed and unexplored territories still remain. Due to the inability of detectors to directly measure the phase, it is necessary to employ optical systems that can convert phase information into intensity information. In the energy range of \(1-{100}\,\hbox {keV}\), phase shifting conversion is typically achieved through the use of gratings8,9,10, crystals11,12,13,14,15,16, random phase modulator (e.g., a piece of sandpaper)17,18, or propagation19,20,21,22 over a certain distance. Unfortunately, at energies exceeding \({100}\,\hbox {keV}\), gratings and crystals demand exceptionally high stability and exhibit relatively low efficiency. Consequently, propagation-based PCI (PB-PCI) is considered as a potential solution and much attention has been paid to this technique.

The PB-PCI requires a sufficiently large propagation distance to exhibit distinguishable Fresnel diffraction fringes. This necessitates the radiation source used for PCI to possess adequate spatial coherence; meanwhile, the image detector should have sufficient spatial resolution19. In order to achieve PCI-based quantitative imaging analysis in industrial and medical fields, inverse Compton scattering (ICS) sources, characterized by moderate footprint and excellent beam qualities, are preferred compared to synchrotron radiation sources and other laboratory sources.

Simulation methods for PB-PCI have been a crucial focus in its development, serving as a vital tool for optimizing imaging parameters. It provides a theoretical basis for the design of imaging systems and guides the interpretation of experimental results. Especially, with the recent emergence of machine learning-based phase retrieval algorithms, simulation methods for PB-PCI can serve as a platform for generating the required training data. In the X-ray region, several simulation methods have been developed for PB-PCI, mainly including the wave optics method23,24,25,26,27,28, the Monte Carlo method29,30,31,32,33, and the hybrid method34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41.

The wave optics method is primarily based on the wave nature of X-ray in classical electrodynamics, focusing on the interference properties of light. This method is generally based on the principles of Fresnel diffraction and efficiently simulates wave propagation using the fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithm. Wave optics methods excel in accurately simulating the Fresnel diffraction patterns. When developing other simulation methods, it is often essential to use the results of wave optics methods as the “gold standard” for evaluating their capabilities. The limitations of wave optics methods are the high computational complexity and the neglect of incoherent scattering effects.

The Monte Carlo method discussed here refers to the particle transport method in traditional absorption-contrast imaging techniques, which offers accurate simulations of particle-matter interactions (Compton scattering, photoelectric effect, and pair production). Previous literature28 has demonstrated that when the spatial resolution of the simulated imaging system is quite low, refraction can be employed as an approximation for the interference effects between the wave-fronts. In essence, the Monte Carlo methods or ray tracing methods are equivalent to the rigorous Huygens-Fresnel principle when the following condition is satisfied:

where FWHM(g) is the full width at half maximum of the over all point spread function (PSF) g of the imaging system, \(\lambda \) is the wave length, and M is the geometric magnification factor, which can be written as:

where \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) are the source-to-sample distance and sample-to-detector distance, respectively. While the Monte Carlo method offers a significant reduction in computational complexity compared to rigorous wave optics methods, it has some limitations. For example, it hinders the ability to evaluate imaging systems with high resolution or large distances \(R_2\).

The hybrid method generally combines the Monte Carlo method and wave optics calculations. Monte Carlo simulation is utilized to conveniently obtain the intensity distribution of the wave field after the object plane. Subsequently, the wave is propagated based on the Huygens-Fresnel principle and the intensity distribution caused by interference effects is calculated. By combining the advantages of both methods, the hybrid method finds wide applications in the simulation of PB-PCI and grating-based PCI34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. However, the hybrid method faces the same problem as the wave optics method. Both methods entail lengthy computational time, which increases with photon energy and makes them impractical for high-energy PCI simulation. Besides, the Monte Carlo methods are inadequate for simulating interference effects and unsuitable for high-resolution imaging simulations. Therefore, an efficiency simulation method that takes the advantages of the hybrid method and can be applied efficiently to high-energy PCI becomes necessity. In this paper, we have improved upon traditional hybrid methods to develop a simulation method, the directional macro-wavefront (DMWF) method, that can cover a broader energy range with higher simulation efficiency. By introducing the concept of the “macro-wavefronts” on the object plane, the issue of chirp function in the Fresnel diffraction integral which constraints on the grid partitioning of the object plane has been effectively addressed. A series of simulation examples demonstrate that the DMWF method exhibits excellent stability across a wide range of sample parameters, showing insensitivity to photon energy and generally lower simulation cost. This method offers a fast simulation approach for high-energy coherent imaging, holding the potential to further advance researches in high-energy PCI.

Method

In principle, PB-PCI is based on the phenomenon of Fresnel diffraction, where the waves modulated by the sample undergo propagation over a certain distance. Assuming the sample is sufficiently thin, the interaction between radiation and matter can be modeled using a two-dimensional transfer function \(T(\xi ,\eta )\)42

where \(\xi \) and \(\eta \) are coordinates in the object plane, \(\Phi (\xi ,\eta )\) and \(\mu (\xi ,\eta )\) refer to the projections of sample’s phase and linear attenuation coefficient, respectively, and \(A(\xi ,\eta )\) represents the amplitude attenuation of the wave field. Furthermore, assuming the light source is an ideal point source located at a distance \(R_1\) upstream of the sample and the light propagates along z-axis direction, the expression for the spatial wave field U(x, y) after propagating a certain distance \(R_2\) after the sample can be obtained from the Fresnel-Kirchhoff integral43, or:

Based on Eq. (5), the light propagation after the sample can be calculated. When the photon energy becomes high, the exponential term in the integral of the equation oscillates rapidly with respect to the transverse coordinate. To numerically compute the intensity value at a point on the image plane, it is a common practice to discretize the object plane wave field, calculate the response at the image plane of light emitted from discrete points on the object plane, and then superimpose these responses. To achieve an accurate sampling, it requires a very dense grid, leading to significant computational and storage costs. This is mainly not due to the difficulty of accurately sampling the wave function on the object plane, but rather because the quadratic exponential term in Eq. (5) is highly sensitive to the object plane coordinates. To elucidate this issue, in this paper, the following chirp function, which is similar to the quadratic exponential term in Eq. (5), is adopted simply for analysis

When the Fresnel number \(N_F = (l/2)^2 /(\lambda z)\) is greater than 0.25, according to the sampling theorem, the sampling criterion for sampling Eq. (6) needs to satisfy the following function44

where \(\Delta x\) is the spacing between samples, z is the propagation distance, and l is the width of the integration region of the Fresnel integral. The integrals involving such chirp function typically have finite integration region because of the limited field of view (FOV) of the image system. As the wavelength decreases, the required sampling density will become intolerable.

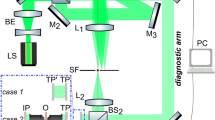

To address this issue, in this paper, we present an efficient hybrid method, the DMWF method. A sketch of the DMWF method is shown in Fig. 1. It takes into account the direction of the wave vector and introduces appropriate integrals to overcome the limitations of the sampling theorem for the quadratic exponential term. The general idea of the DMWF method is similar to other hybrid methods, it involves first obtaining the wave function distribution on the object plane using Monte Carlo methods, followed by numerically calculating the wave propagation from the object plane to the detector. These two primary components, methods of Monte Carlo and wave optics, will be elaborated below.

The sketch of the DMWF method. The method is divided into two parts. The photon transport and the photon-matter interaction before the object plane are simulated using Monte Carlo method. In the second part, wave optics is used to calculate the intensity distribution from the grid on the object plane to the image plane.

Monte Carlo part

Two main processes, photon generation and source-to-sample transportation of photons, are simulated using Monte Carlo method based on Geant445,46. Firstly, the photons are sampled according to the properties of the ICS source. For the ICS source, photons are generated through the collision of laser and electrons. Here, we only consider the ICS source under the case of head-on collisions. Since both the laser and the electron spots follow 2D Gaussian distributions, the scattered photons also follows a 2D Gaussian distribution. The RMS focal spot size of light source \(\sigma _{X,x}\) is written as47:

where \(\sigma _{l,x}\) and \(\sigma _{e,x}\) are, respectively, the RMS beam spot sizes of laser and electron in lateral direction. The momentum distribution of ICS photons can be described as follows29:

when the laser is linearly polarized and the linear Compton scattering condition is satisfied. In Eq. (9), \(\gamma \) is the Lorentz factor of the electron, \(\beta \) is the speed of the electron normalized by c, and \(\theta \) and \( \phi \) are the polar and azimuth angles of the scattered photon, respectively. The photon energy \(E_X\) distribution of the scattered photons is related to the polar angle \(\theta \) ideally48:

where \(E_l\) is the energy of the laser photons, \(a_0\) is the magnitude of the normalized vector potential of the laser. In reality, the energy spectrum of ICS sources is more complex and requires further consideration of the effects of laser bandwidth and focusing, as well as electron beam energy spread and emittance. In the case where the polar angle is not very large, such as when using a small collimation aperture, the energy spectrum can be approximately considered as a Gaussian distribution.

After sampling, similar to traditional absorption contrast imaging simulations, the transportation of each photon through the sample and to the object plane behind the sample is simulated. For photons in the X/\(\gamma \)-ray energy range, the physical processes involved in the interaction between photons and the sample are mainly composed of coherent scattering, Compton scattering, photoelectric effect, and pair production. During the particle transport process, the phase shift of photon is calculated based on the length \(l_i\) of each segment of the particle’s trajectory. Multiplying the recorded length with corresponding real part of complex refractive index decrement \(\delta \) and wave number k, the individual phase shift can be obtained. The total phase shift \(\Phi \) is the accumulation of individual phase shift, written as:

where \(\delta \) is obtained by49

where \(\rho \) is the density of the material, \(N_A\) is Avogadro constant, and \(X_i\) is the mass fraction of the atoms with mass number \(A_i\). \(f_{1,i}\) is the atomic scatter factor, which is obtained from the database DABAX for X-ray applications50. Besides, the refraction of photons is also considered at material boundaries. The refraction angle of a photon is calculated by the Snell’s law51:

where \(\theta _1\) and \(\theta _2\) are the incident and exitant angles, respectively, \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the refractive indices of the two media, and \(\Re (n)\) represent the real part (\(1-\delta \)) of the complex refractive index. A geant4 class for the X/\(\gamma \)-ray photon refraction process has been developed for the PCI simulation in our laboratory. During the simulation, if the refractive indexes of the previous and post step positions are not the same, a calculation of Snell’s law is triggered to determine the direction of exitant photon. The plane just behind the sample, which is commonly known as the object plane, is divided into a grid of pixels \(N_o \times N_o\). The assignment of photon is based on the pixel (i, j) that it passes through, where \(0\le i,j<N_o\). The energy and phase shift information of a photon, when reaching the grid pixel (i, j), is stored to calculate the average phase shift \(\Phi _{i,j}\) and cumulative energy \(E_{i,j}\). At the end of the Monte Carlo part, a discretized wave-field on the object plane is obtained, comprising phase shift and energy information at each grid pixel.

Wave optics part

The wave optics part involves the simulation of the wave-field propagation from the object plane to the image plane (the detector plane). For simplicity, the scenario where the object is illuminated by an ideal monochromatic point source is considered firstly. Each grid pixel in the object plane is treated as a macro-wavefront, and propagation calculations are performed. This is similar to the treatment in partial coherence simulation for synchrotron radiation52,53,54. In contrast to other hybrid simulation methods, we consider that the waves are emitted from every position within the grid to form a macro-wavefront, and the waves in the same grid pixel have the same amplitude \(A\left( \xi _i, \eta _j\right) =\sqrt{E_{i,j}}\) and the same derivative of phase shift \((\frac{\partial \Phi }{\partial \xi },\frac{\partial \Phi }{\partial \eta })\big |_{i,j}\), where the lateral coordinate of the center point of each pixel is \((\xi _i,\eta _j)\). This implies that the waves within an individual pixel possess same amplitude and propagation direction. The derivative of phase shift is approximated by the following equation:

where \(d\xi ,d\eta \) is the lateral pixel size of the object plane. Consequently, we can obtain the phase shift value at any arbitrary point \((\xi ,\eta )\) within the pixel (i, j), written as:

According to Eq. (5), the propagation of the macro-wavefront of a single pixel in vacuum can be expressed as

where \((x_0,y_0)\) is the photon exit position on the source plane, which typically is (0, 0) for an ideal point source. Using mathematica software55 we can find the integral results analytically.

where

and \({\text {Erfi}}(x)\) is imaginary error function. The intensity on the detector is given by

Since PB-PCI images are generally diffraction fringes containing high frequency oscillation, the image plane must have a small enough sampling interval to obtain a correct image. In general, the sampling interval \(\Delta x_{det} \) needs to be less than the width of the first Fresnel fringes,

For a real imaging system, further processing is required for the image. Photons generated by an ICS source typically have random phases, so the photons emitted from different positions of the source is completely incoherent. The ideal image in Eq. (19) will be convolved with the source distribution function (typically 2D Gaussian distribution with \(\mu =0\) and \(\sigma =(M-1)\sigma _{X,x}\)) to account for the blurring effect of the source56,57. The blurring effect of the detector also needs to be considered, its PSF also needs to be convolved. For non-monochromatic beams, it is necessary to superimpose images obtained at different energies according to the source spectrum to obtain the final result. This process will greatly consume computational time. Fortunately, the images produced by PB-PCI are insensitive to energy variations. Quasi-monochromatic ICS sources can also be simulated according to monochromatic light sources to a certain extent19.

Results and discussion

Several examples are provided to illustrate the broad reliability of the simulation method.

Validation of the DMWF method

To validate the DMWF method, we simulate the condition of an X-ray PCI experiment, which was conducted at the Tsinghua Thomson-scattering X-ray source (TTX)29. The sample is a Teflon cylinder with diameter of \({6.0}\,\hbox {mm}\) and height of \({6.0}\,\hbox {mm}\), whose photo and sketch are shown in Fig 2 a and b, respectively. There were three through-holes and one blind hole inside the cylinder, with diameters of \({1.5}\,\hbox {mm}\), \({1.0}\,\hbox {mm}\), \({0.5}\,\hbox {mm}\), and \({0.2}\,\hbox {mm}\), respectively, and the depth of the blind-hole is \(\sim {3}\,\hbox {mm}\). Below the sample, there was a cylindrical handle with diameter of \({2}\,\hbox {mm}\), which was used for secure fixation of the phantom on the imaging platform.

The imaging plate detector (Fuji film) was used for its relative small pixel (\({25}\,{\mu }\hbox {m/pixel}\)) and free of electrical noise. In the experiment, the X-ray energy is \(\sim {25}\,\hbox {keV}\) with an rms bandwidth of \(2.3\%\)58, and the rms focal spot size is \(\sim {10}\,{\mu }\hbox {m} \). The source-to-sample distance \(R_1\) is \({2.1}\,\hbox {m}\), and the sample-to-detector distance \(R_2\) is \({0.87}\,\hbox {m}\). The number of simulated photons is \(8\times 10^{10}\). The object plane and the image plane are divided into \(1500\times 1500\) and \(5000\times 5000\) grid, respectively, according to one-dimensional pre-simulations. After convolution with the system’s PSF, the image is further down-sampled (the intensities of several small grids are summed as the intensity of the larger grid) to \(400\times 400\) to match the detector pixel size. The images obtained from both simulation and experiment are shown in Fig. 2c and d. The images were normalized according to the source intensity distribution.

As depicted in Fig. 2, the simulation result agrees well with the experimental result except slight deviations in the positions of the through-holes in the imaging results, which can be attributed to the machining errors in the sample. Additionally, there exist some rounded edges and burrs at the sample boundaries. Realistic factors ultimately lead to a reduction in the enhancement effect at the edges of the experimental results. The horizontal intensity profiles of the simulation and the experiment around the center of the images which are averaged vertically over 20 pixels is illustrated in Fig. 3.

From Fig. 3, it can be observed that the trends of the two curves are roughly consistent, and the intensity attenuation caused by the sample also aligns. However, the simulated result exhibits a stronger edge enhancement effect at the edges of the sample and misalignment near the holes compared to the experimental result, which may be attributed to the inadequate consideration of noise and machining errors of the sample. In general, the simulation is in good agreement with the experimental result , which also proves the feasibility of this method.

Convergence of the DMWF method

In order to effectively apply the DMWF method, it is imperative to investigate the adaptability of this innovation under varying conditions, especially high-energy condition. In theory, the DMWF no longer suffers from the issue of extremely small sampling intervals caused by the chirp function. However, a certain number of grids still need to be allocated to ensure a decent reproduction of the sample’s transfer function T. To investigate the relationship between the characteristics of image system and the number of grids on the object plane \(N_o\) when the method converged, we designed several ideal transfer functions to simulate phase-contrast images after propagating a certain distance, examining the method’s convergence capabilities under different parameters and comparing with the traditional wave optics method. It should be noted that the core innovation of the DMWF method lies in its clever handling of the Fresnel diffraction integrals. Hence, we mainly focus on examining the differences between the DMWF’s wave optics part and conventional wave optics methods.

The conventional wave optics (WO) methods based on Eqs. (4) and (5) is applied for comparison, which uses the theoretical transfer function in Eq. (5) to calculate the image on the image plane. Due to the complexity of the imaging objects, it is challenging to analytically determine their imaging results. Therefore it is still necessary to divide the object plane into grids and calculate the propagation of waves from each grid to the image plane. The WO method and the related hybrid method is widely employed in previous PCI simulations34,35. Therefore, the required mesh number \(N_o\) (related to the time and space cost required for simulation) of the two methods are compared to demonstrate the superiority of the DMWF method.

Stability of the DMWF method’s convergence with different imaging samples

In this section, we will investigate the impact of sample-induced attenuation and phase shift on the convergence capability of the DMWF method to demonstrate its stability under various imaging conditions. For simplicity, we suppose three types of imaged samples whose transfer functions satisfy the Fermi-Dirac distribution function shown in Table 1.

This implies that the transfer function is a step function, and the steepness of the attenuation or phase shift is controlled by a. Utilizing ideal transfer functional analysis obviates the need for simulations in the Monte Carlo part, allowing for direct computation of the wave optics part, which is the primary focus of this section. The image system is set with \(R_1={20}\,\hbox {m}\), \(R_2={20}\,\hbox {m}\), and the energy of the light source is set as \({1}\,\hbox {MeV}\). The size of object plane and image plane are \({0.1}\,\hbox {mm} \times {0.1}\,\hbox {mm}\) and \({0.2}\,\hbox {mm}\times {0.2}\,\hbox {mm}\) respectively, and the image plane is divided into a \(1000\times 1000\) grid. Simulations are conducted with the mesh number \(N_o= 10,20,50,70,100,200,500,700,...,50,000\). The result fringes with \(N_o=100,000\) of the DMWF method are taken as the ground truth to determine the convergence of two methods.

Case A is mainly used to investigate the impact of the gradient of intensity attenuation on the convergence of the two methods. Smaller a corresponds to larger intensity gradients of the steps. The convergence curves of the two methods, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the ground truth and the imaging results, are shown in Fig. 4a. As \(N_o\) increases, the imaging results of both methods approach the ground truth. It can be observed that the influence of the intensity attenuation gradient related to a on convergence of the two methods is relatively weak. Furthermore, the DMWF method consistently maintains a significant advantage in convergence compared to the WO method. For the WO method, around \(N_o\sim 4\times 10^2\), the simulation results rapidly converge towards the ground truth, which corresponds precisely to the maximum sampling interval required by the sampling theorem Eq. (7). However, the DMWF method maintains a high correlation coefficient starting from a small \(N_o\). The required \(N_o\) for the DMWF method to achieve a correlation coefficient above 0.99 is likely one fifth of that for the WO method. Therefore, for a typical two-dimensional object plane of \(N_o \times N_o\), the computational time and storage space of the DMWF method will be reduced by a factor of 25 compared to the WO method.

Compared to intensity attenuation, the impact of phase shift on the simulation is likely to be more substantial. This is because under typical imaging parameters, the phase shift of rays after passing through an object is significantly larger than \(2\pi \). Consequently, this leads to rapid oscillations of the corresponding complex angle in the transverse direction, thereby affecting the convergence of the simulation methods. In cases B and C, we further investigated the influence of the phase shift and its gradient on the convergence of the methods. The convergence curves of cases B and C are shown in Fig. 4b and c.

In Case B, different values of a represent distinct lateral phase gradients, which correspond to the refraction of light. In PB-PCI, refraction is a crucial component of the phase-contrast signal. In case C, the minimum phase value has been altered. It can be seen that the advantage of the DMWF method is more obvious when the absolute value of the phase is larger, or the absolute value of phase gradient is smaller. The DMWF method converges smoothly in these instances, albeit at a slower rate compared to case A. A series of data can attest that DMWF converges smoothly across a variety of sample parameters. Simultaneously, there is little difference in the required \(N_o\) for accurate simulations.

Energy adaptability and computation cost of the DMWF method

As mentioned earlier, due to the constraints of the sampling theorem, it is challengeable for the WO method to simulate high-energy PCI. For comparison, both the DMWF and the WO methods were used to simulate PCI at a series of photon energy. It is worth noting that in order to ensure the same sample transfer function at different energies, an ideal transfer function in the form of the Fermi-Dirac distribution function is used:

The image geometry was set with the \(R_1={2}\,\hbox {m}\), and \(R_2={2}\,\hbox {m}\). The settings of other parameters are consistent with those in the previous section. The convergence curves of the two methods are calculated, and the results are shown in Fig. 5a.

(a) The Pearson correlation coefficient between the ground truth and the fringes with different \(N_o\) for the two methods. (b) Computing times of two methods under different energy and \(N_o\). (c) Minimum \(N_o\) and corresponding computing time when the Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.98. Solid line: the DMWF method, dashed line: the WO method.

As depicted in Fig. 5a, the convergence behavior of the WO method closely aligns with the predictions of the sampling theorem in Eq. (7). With the increase of photon energy, the convergence of the WO method becomes increasingly challenging. On the other hand, the DMWF method appears to be unaffected by photon energy, maintaining a nearly consistent convergence rate across different energy regions. The computing times of these two methods are shown in Fig. 5b, which both increase linearly with \(N_o\). While the DMWF method consumes more computing time than the WO method under the same parameters, the DMWF method requires a smaller \(N_o\) to achieve a high correlation coefficient, especially at higher energies. To reach the corresponding minimum requirement of \(N_o\), the DMWF needs much less computing time than the WO method, as shown in Fig. 5c. It is worth emphasizing that the transfer functions of the simulated phantoms in this section are one-dimensional, so all grid divisions are also one-dimensional. For two-dimensional samples or light sources, the computation cost advantage of the DMWF method will be further increased. When imaging real samples, it is necessary to obtain their transfer function using the Monte Carlo part of DMWF first. The computation cost of the Monte Carlo part of DMWF is roughly equivalent to that of the traditional Monte Carlo method and the Monte Carlo part of traditional hybrid methods, which is dependent on the number of simulated photons. The DMWF method uses the innovative wave optics part that significantly reduces the computation cost of the wave optics part and shows excellent energy adaptability while simultaneously simulating the interference effect.

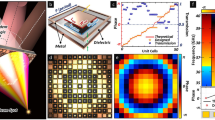

Metallic sample of \(\gamma \)-ray PCI

In the above section, the DMWF method has been demonstrated to be applicable to a higher energy range, providing us with the possibility to simulate \(\gamma \)-ray PCI at a relatively low cost. In this section, we simulated \(\gamma \)-ray PCI of a copper sample as an application example of this method. The parameters are taken from the very compact ICS Gamma ray source (VIGAS) system under construction in Tsinghua University59. The VIGAS system is an ICS source, which can generate \(0.2-{4.8}\,\hbox {MeV}\) soft \(\gamma \)-ray. The RMS focal spot size \(\sigma _{X,x}\) is approximately \({10}\,{\mu }\hbox {m}\), and the energy spread is \(1.5\%\) (RMS, Gaussian). The photon energy was set to \({1}\,\hbox {MeV}\), and \(R_1=R_2={20}\,\hbox {m}\). The imaging object was a copper tube with an inner diameter of \({1}\,\hbox {mm}\) and an outer diameter of \({2}\,\hbox {mm}\). Due to the insensitivity of PB-PCI to energy spectra and the quasi-monochromatic characteristic of an ICS spectrum, the simulation disregarded the energy spread of the source. The focal spot size of the source(\(\sigma = {10}\,{\mu }\hbox {m}\), RMS, Gaussian) and the PSF of the detector (\(\sigma = {10}\,{\mu }\hbox {m}\), RMS, Gaussian) were taken into account in the simulation. This is equivalent to a Gaussian blur with \(\sigma ={14.14}\,{\mu }\hbox {m}\). The image simulated using the DMWF method is shown in Fig. 6a. The number of simulated photons is \(8\times 10^{10}\).

The intensity profile along the horizontal line passing through the center of the image is shown in Fig. 6b. The object plane grid is partitioned into a \(2000\times 2000\) grid to ensure the accuracy of the simulated image. The image plane is divided into a \(2000\times 2000\) grid according to Eq. (20). After convolution with the system’s PSF, the image is further down-sampled to \(500\times 500\), corresponding to a \({10}\,{\mu }\hbox {m}\) pixel size. In the simulated image, it is evident that there is a significant edge enhancement at the sample edges, which would be beneficial for identifying material boundaries.

Furthermore, we performed a reconstruction of the sample’s thickness profile based on the simulated images using PAD-PA method of PITRE software2,60. For a homogeneous sample consisting of only one material, the reconstruction can be achieved using a single image. The reconstruction result is shown in Fig. 6c. It can be seen that the reconstructed thickness profile generally aligns with the theoretical expectation. This indicates that the DMWF method demonstrates good accuracy in PCI simulation with metallic sample.

Conclusion

We have developed an efficient PB-PCI simulation method, called DMWF, which is suitable for a wider energy range than conventional WO methods and hybrid methods and has good applicability to various samples. The simulation method is a hybrid approach. Firstly, the image on the object plane is obtained through Monte Carlo simulation, and then the final image is calculated using the fast macro-wavefront propagation. This method partially overcomes the sampling limitations of the chirp function in Fresnel diffraction, significantly reducing the spatio-temporal complexity of simulating PB-PCI interference effects. Some results are presented to demonstrate the adaptability and accuracy of the simulation method. In comparison to the WO method and other related hybrid methods that utilizes traditional Fresnel diffraction integrals, the DMWF method exhibits superior energy adaptability and reduces computation cost. However, in order to simulate the interference phenomena, the computation cost may still be higher than the traditional Monte Carlo method. Although the DMWF method breaks through the sampling criterion of object plane, the grid division of the image plane is still limited by sampling criterion. Especially when imaging larger samples, the simulation still takes time.

The DMWF method itself also holds significant potential for improvement. Firstly, the method can be implemented using large-scale matrix computations, where vectorized parallel methods and GPU acceleration could significantly speed up the simulations. Secondly, to further speed up the computation and reduce storage requirements, one could emulate finite element methods by adaptively partitioning the object plane with grids of varying sizes to save computation costs in regions of the image with less pronounced features. Thirdly, the Monte Carlo part of the DMWF method currently supports the import of most simple models as imaging samples. To expand its application in the medical field, it is necessary to further develop the import interface for voxelized models. In the near future, many high-energy and highly coherent ICS sources59,61,62 and synchrotron sources63,64,65 will be operational, making high-energy X/\(\gamma \)-ray PCI a significant scientific objective. The DMWF method demonstrates significant advantages in high-energy PCI simulations and can be easily adapted to other types of light sources, laying a foundation for further research of high-energy X/\(\gamma \)-ray PCI in the future.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Michette, A. G. X-ray science and technology (Philadelphia : Institute of Physics Pub., Philadelphia, 1993).

Paganin, D., Mayo, S. C., Gureyev, T. E., Miller, P. R. & Wilkins, S. W. Simultaneous phase and amplitude extraction from a single defocused image of a homogeneous object. J. Microsc. Oxford 206, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2818.2002.01010.x (2002).

Burvall, A., Lundström, U., Takman, P. A. C., Larsson, D. H. & Hertz, H. M. Phase retrieval in x-ray phase-contrast imaging suitable for tomography. Opt. Express 19, 10359–10376. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.19.010359 (2011).

Leatham, T. A., Paganin, D. M. & Morgan, K. S. X-ray dark-field and phase retrieval without optics, via the fokker-planck equation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 1681–1695. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2023.3234901 (2023).

Thüring, T., Abis, M., Wang, Z., David, C. & Stampanoni, M. X-ray phase-contrast imaging at 100 kev on a conventional source. Sci. Rep. 4, 5198. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05198 (2014).

Astolfo, A. et al. Large field of view, fast and low dose multimodal phase-contrast imaging at high x-ray energy. Sci. Rep. 7, 2187. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02412-w (2017).

Wang, H., Kashyap, Y., Cai, B. & Sawhney, K. High energy x-ray phase and dark-field imaging using a random absorption mask. Sci. Rep. 6, 30581. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30581 (2016).

Pfeiffer, F. et al. X-ray dark-field and phase-contrast imaging using a grating interferometer. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 102006. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3115639 (2009).

David, C., Nöhammer, B., Solak, H. H. & Ziegler, E. Differential x-ray phase contrast imaging using a shearing interferometer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 3287–3289. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1516611 (2002).

Pfeiffer, F., Weitkamp, T., Bunk, O. & David, C. Phase retrieval and differential phase-contrast imaging with low-brilliance X-ray sources. Nat. Phys. 2, 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys265 (2006).

Momose, A. Demonstration of phase-contrast x-ray computed tomography using an x-ray interferometer. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 352, 622–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(95)90017-9 (1995).

Bonse, U. & Hart, M. An X-ray interferometer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 6, 155–156. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1754212 (1965).

Chapman, D. et al. Diffraction enhanced x-ray imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 42, 2015–2025. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/42/11/001 (1997).

Förster, E., Goetz, K. & Zaumseil, P. Double crystal diffractometry for the characterization of targets for laser fusion experiments. Krist. Tech. 15, 937–945. https://doi.org/10.1002/crat.19800150812 (1980).

Somenkov, V., Tkalich, A. K., Shil’shtein, S. & Alferieff, M. E. Refraction contrast in X-ray introscopy. Sov. Phys. Tech. Phys. 3, 1309–1311 (1991).

Ingal, V. N. & Beliaevskaya, E. A. X-ray plane-wave topography observation of the phase contrast from a non-crystalline object. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 28, 2314–2317. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/28/11/012 (1995).

Wang, F. et al. Speckle-tracking x-ray phase-contrast imaging for samples with obvious edge-enhancement effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 174101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4997970 (2017).

Morgan, K., Paganin, D. & Siu, K. X-ray phase imaging with a paper analyser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 124102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3694918 (2012).

Wilkins, S. W., Gureyev, T. E., Gao, D., Pogany, A. & Stevenson, A. W. Phase-contrast imaging using polychromatic hard x-rays. Nature[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1038/384335a0 (1996).

Mayo, S. C., Stevenson, A. W. & Wilkins, S. W. In-line phase-contrast x-ray imaging and tomography for materials science. Materials 5, 937–965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5050937 (2012).

Snigirev, A., Snigireva, I., Kohn, V., Kuznetsov, S. & Schelokov, I. On the possibilities of x-ray phase contrast microimaging by coherent high-energy synchrotron radiation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 66, 5486–5492. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1146073 (1995).

Cloetens, P., Barrett, R., Baruchel, J., Guigay, J.-P. & Schlenker, M. Phase objects in synchrotron radiation hard x-ray imaging. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 29, 133. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/29/1/023 (1996).

Gong, S., Gao, F., Zhou, Z. & Miao, H. Numerical simulation of x-ray in-line phase-contrast imaging. In 2009 2nd International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Informatics, 1-5, https://doi.org/10.1109/BMEI.2009.5305064 (2009).

Golosio, B. et al. Phase contrast imaging simulation and measurements using polychromatic sources with small source-object distances. J. Appl. Phys.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3006130 (2008).

Vittoria, F. A. et al. Strategies for efficient and fast wave optics simulation of coded-aperture and other x-ray phase-contrast imaging methods. Appl. Opt.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.52.006940 (2013).

Häggmark, I. et al. Phase-contrast virtual chest radiography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2210214120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2210214120 (2023).

Häggmark, I., Shaker, K. & Hertz, H. M. In silico phase-contrast x-ray imaging of anthropomorphic voxel-based phantoms. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2020.3031318 (2021).

Peterzol, A., Berthier, J., Duvauchelle, P., Ferrero, C. & Babot, D. X-ray phase contrast image simulation. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 254, 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2006.11.042 (2007).

Chi, Z. et al. Recent progress of phase-contrast imaging at Tsinghua Thomson-scattering X-ray source. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 402, 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2017.02.062 (2017).

Wang, Z., Huang, Z., Zhang, L., Chen, Z. & Kang, K. Implement x-ray refraction effect in geant4 for phase contrast imaging. In Proc. IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. Conf. Rec. (NSS/MIC), 2395-2398, https://doi.org/10.1109/NSSMIC.2009.5402180 (2009).

Yan, J. et al. Monte carlo-based simulation of x-ray phase-contrast imaging for diagnosing cold fuel layer in cryogenic implosions. AIP Adv. 9, 025311. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5087615 (2019).

Brombal, L. et al. X-ray differential phase-contrast imaging simulations with geant4. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 55, 045102. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ac2e8a (2021).

Sanctorum, J., Sijbers, J. & Beenhouwer, J. D. Virtual grating approach for monte carlo simulations of edge illumination-based x-ray phase contrast imaging. Opt. Express 30, 38695–38708. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.472145 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. A simulation method of gamma-ray phase contrast imaging for metal samples. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1053, 168321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2023.168321 (2023).

Peter, S. et al. Combining monte carlo methods with coherent wave optics for the simulation of phase-sensitive x-ray imaging. J. Synchrotron Radiat.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600577514000952 (2014).

Pietersoone, E., Létang, J. M., Rit, S., Brun, E. & Langer, M. Combining wave and particle effects in the simulation of x-ray phase contrast-a review. Instrum. 8, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments8010008 (2024).

Cipiccia, S., Vittoria, F. A., Weikum, M., Olivo, A. & Jaroszynski, D. A. Inclusion of coherence in monte carlo models for simulation of x-ray phase contrast imaging. Opt. Express 22, 23480–8. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.023480 (2014).

Langer, M., Cen, Z., Rit, S. & Létang, J. M. Towards monte carlo simulation of x-ray phase contrast using gate. Opt. Express 28, 14522. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.391471 (2020).

Bartl, P. et al. Simulation of x-ray phase-contrast imaging using grating-interferometry. In 2009 IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. Conf. Rec. (NSS/MIC), 3577-3580, https://doi.org/10.1109/NSSMIC.2009.5401821 (2009).

Sanctorum, J., De Beenhouwer, J. & Sijbers, J. X-ray phase-contrast simulations of fibrous phantoms using gate. In 2018 IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. Conf. Rec. (NSS/MIC), 1-5, https://doi.org/10.1109/NSSMIC.2018.8824641 (2018).

Sanctorum, J., Beenhouwer, J. D. & Sijbers, J. X-ray phase contrast simulation for grating-based interferometry using gate. Opt. Express 28, 33390–33412. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.392337 (2020).

Pogany, A., Gao, D. & Wilkins, S. Contrast and resolution in imaging with a microfocus x-ray source. Rev. Sci. Instrum.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1148194 (1997).

Born, M. & Wolf, E. Principles of Optics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2019), 7 edn.

Goodman, J. W. Introduction to Fourier optics. Fourier optics (New York: W.H. Freeman, Macmillan Learning, 2017), 4 edn.

Allison, J. et al. Geant4 developments and applications. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 53, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2006.869826 (2006).

Agostinelli, S. et al. Geant4-a simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 506, 250–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8 (2003).

Zhang, Z. et al. In-line phase-contrast imaging based on tsinghua thomson scattering x-ray source. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 083307–083307. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4893658 (2014).

Ride, S. K., Esarey, E. & Baine, M. Thomson scattering of intense lasers from electron beams at arbitrary interaction angles. Phys. Rev. E 52, 5425–5442. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.52.5425 (1995).

Martz, H. E., Logan, C. M., Schneberk, D. J. & Shull, P. J. X-Ray Imaging: Fundamentals, Industrial Techniques and Applications (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2016).

recent developments of the x-ray optics software toolkit. RÃo, M. S. D. & Dejus, R. J. Xop v2.4. In Advances in Computational Methods for X-Ray Optics II8141, 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.893911 (SPIE (2011).

Hecht, E. Optics: Pearson New International Edition (Pearson Education UK, 2013).

Meng, X. et al. Mutual optical intensity propagation through non-ideal mirrors. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 24, 954–962. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577517010281 (2017).

Meng, X. et al. Numerical analysis of partially coherent radiation at soft x-ray beamline. Opt. Express 23, 29675–29686. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.029675 (2015).

Ren, J. et al. In-plane wavevector distribution in partially coherent x-ray propagation. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 26, 1198–1207. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577519005253 (2019).

Inc., W. R. Mathematica, Version 14.0. Champaign, IL, 2024.

Wu, X. & Liu, H. A new theory of phase-contrast x-ray imaging based on wigner distributions. Med. Phys. 31, 2378–2384. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.1776672 (2004).

Zuo, C. et al. Transport of intensity equation: A tutorial. Opt. Laser Eng. 135, 106187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2020.106187 (2020).

Chi, Z. et al. Diffraction based method to reconstruct the spectrum of the thomson scattering x-ray source. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 88, 045110. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4981131 (2017).

Du, Y. C. et al. A very compact inverse compton scattering gamma-ray source. High Power Laser Part Beams 34, 104010–1, https://doi.org/10.11884/hplpb202234.220132 (2022).

Chen, R. C. et al. Pitre: Software for phase-sensitive x-ray image processing and tomography reconstruction. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 19, 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0909049512029731 (2012).

Geddes, C. et al.Impact of Monoenergetic Photon Sources on Nonproliferation Applications Final Report. INL/EXT-17-41137 (2017).

Tanaka, K. A. et al. Current status and highlights of the eli-np research program. Matter Radiat. Extremes 5, 024402. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5093535 (2020).

Jiao, Y. et al. The heps project. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 25, 1611–1618. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577518012110 (2018).

Hettel, R. et al. Status of the aps-u project. In Proceedings of the 12th International Particle Accelerator Conference. Campinas, Brazil, 7–12 (2021).

Willmott, P. R. & Braun, H. Sls 2.0-the upgrade of the swiss light source. Synchrotron Radiat. News[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1080/08940886.2024.2312059 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.12027902 and No.12305163).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of this research. Material preparation, programming, data collection and analysis were performed by Jiayi Sun, Hao Ding, Zhijun Chi and Zhan Shen. The main manuscript was written by Jiayi Sun and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, J., Ding, H., Chi, Z. et al. A hybrid simulation method towards the gamma ray phase contrast imaging for metallic material. Sci Rep 14, 21159 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72090-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72090-y