Abstract

Land use and land cover change (LULCC) have profoundly altered land surface properties and ecosystem functions, including carbon and water production. While mapping these changes from local to global scales has become more achievable due to advancements in earth observations and remote sensing, linking land cover changes to ecosystem functions remains challenging, especially at regional scale. Our study attempts to fill this gap by employing a computationally efficient method and two types of widely used high-resolution satellite images. We first investigated the contribution of landscape composition to ecosystem function by examining how land cover and proportion affected gross primary production (GPP) and evapotranspiration (ET) at six macro-landscapes in Mongolia and Kazakhstan. We hypothesized that both ecosystem and landscape GPP and ET are disproportionate to their composition and, therefore, changes in land cover will have asymmetrical influences on landscape functions. We leveraged a computational-friendly linear downscaling approach to align the coarse spatial resolution of MODIS (500 m) with a fine-grain and localized land cover map developed from Landsat (30 m) for six provinces in countries where intensive LULCC occurred in recent decades. By establishing two metrics—function to composition ratio (F/C) and function to changes in composition change (ΔF/ΔC)—we tested our hypothesis and evaluated the impact of land cover change on ecosystem functions within and among the landscapes. Our results show three major themes. (1) The five land cover types have signature downscaled ET and GPP that appears to vary between the two countries as well as within each country. (2) F/C of ET and GPP of forests is statistically greater than 1 (i.e., over-contributing), whereas F/C of grasslands and croplands is close to or slightly less than 1 (i.e., under-contribution). F/C of barrens is clearly lower than 1 but greater than zero. Specifically, a unit of forest generates 1.085 unit of ET and 1.123 unit of GPP, a unit of grassland generates 0.993 unit of ET and GPP, and a unit of cropland produces 0.987 unit of ET and 0.983 unit of GPP. The divergent F/C values among the land cover classes support the hypothesis that landscape function is disproportionate to its composition. (3) ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC of forests and croplands showed negative values, while grasslands and barrens showed positive values, indicating that converting a unit of forest to other land cover leads to a decrease in ET and GPP, while converting units of grassland or barren to other land cover classes will result in increased ET and GPP. This linear downscaling approach for calculating F/C and ΔF/ΔC is labor-saving and cost-effective for rapid assessment on the impact of land use land cover change on ecosystem functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Land use and land cover change (LULCC) have profoundly and extensively modified land surface properties and, consequently, ecosystem functions. Direct alterations of land surfaces during LULCC include changes in vegetation (e.g., cover type, species composition, canopies, biomass), soil (e.g., bare coverage, texture) and microclimate (land surface temperature, vapor pressure deficit), whereas indirect influences touch all aspects of ecosystem processes and functions1,2,3,4,5. Scientific investigations on LULCC, as well as its causes and consequences on ecosystems properties, people and societies have been a central concern for several decades 6,7,8,9. Across the Asia Drylands Belt (ADB), intensive and extensive LULCC has been jointly driven by rapid economic development, population growth, urban expansion, abrupt political shifts, and climate change10,11. Here the water-stressed ecosystems are under extreme pressure, with predictions of a drier and warmer climate and more frequent extreme climate events (e.g., droughts, heatwaves, dzuds), anticipating additional pressures on fragile ecosystems and societies with relatively less-advanced infrastructures. As in all the terrestrial regions, the most pressing question has been: What are the independent and interactive forcings from LULCC and climate change on ecosystems and societies? Taking a macroecology approach, we focus on the spatial and temporal changes of two major terrestrial ecosystem functions: gross primary production (GPP) and evapotranspiration (ET). GPP, the largest carbon flux term, is total carbon uptake through photosynthesis. ET is the sum of water loss from the land surface to the atmosphere via evaporation and transpiration. Both GPP and ET are tightly coupled with LULCC and climate. Our specific study objectives are to: (1) quantify the magnitude of GPP and ET in major land cover classes in different regions and time periods; (2) explore how different direction of land cover changes (LCC) may result in similar GPP and ET in different parts of the ADB; and (3) identify the key LCCs that may cause disproportional changes in GPP and ET.

Rich earth observation satellites provide regular reflectance of land surfaces across continuous space, which can be used to model GPP, ET, land cover, and other properties. Among the remote sensing products, Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) provides GPP and ET products at 500-m spatial resolution and 8-day frequency. Land cover maps and other products are also available. Ideally, we should be able to use land cover maps to examine the changes in ET or GPP. Unfortunately, the coarse spatial resolution from MODIS often prevents us from connecting GPP or ET directly to a specific land cover because many ecosystems are smaller than 500 m. Fortunately, NASA’s Landsat and ESA’s Sentinel satellites provide 10–30 m resolution reflectance measures for developing accurate land cover classifications12,13,14. Therefore, if MODIS GPP or ET can be downscaled to 30 m resolution, we can compare the interdependent changes between LCC and ecosystem functions.

Here we leverage a computational-friendly linear downscaling approach15,16,17,18 to align the coarse resolution GPP and ET products with high-resolution land cover maps of Kazakhstan and Mongolia19 to examine the changes in ecosystem functions with LULCC. Two specific hypotheses will be tested on how ecosystem GPP and ET might be affected by landscape composition and land cover changes. First, ecosystem functional contributions of a land cover type (Fi) are not proportional to its proportion of the land area (Ci) of a landscape or a region (where i indicates a specific land cover class). While this hypothesis is intuitive, a more interesting premise is that these disproportionate contributions vary significantly among the landscapes of a region and/or among regions. This hypothesis can be mathematically expressed as.

Lessons learned from testing this hypothesis in multiple regions of Kazakhstan and Mongolia will have profound consequences on understanding and managing landscapes. Our second hypothesis is that changes in landscape function are not equally caused by the changes of a land cover class (i):

In other words, a same amount of land conversion from a cover type will yield very different ΔF depending on the cover type after conversion. By testing this hypothesis, we can directly connect land cover change (∆Ci) to functional consequences (ΔFi). Similarly, the unequal contributions of a cover type may vary significantly among the regions. These hypotheses are tested in grassland biomes20 in six provinces in Kazakhstan and Mongolia (three provinces in each country) where detailed land cover classes for the past three decades are available19.

Methods

Study area

We selected three provinces (each country) as our macrosystems in Kazakhstan and Mongolia based on the climate, dominant vegetation and soils, and socioeconomic positions in the country. Kazakhstan is the largest landlocked country in the world (2,724,900 km2) and divided into 13 regions (provinces). It has a climate ranging from hot summer humid continental climate in the north to cold semi-arid climate in the south according to Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification (Table 1). Mongolia is the second largest landlocked country (1,564,116 km2) and divided into 21 Aimags (provinces). It ranges from Monsoon-influenced subarctic climate to semi-arid climate in the middle, to cold desert climate in the south. The six study provinces are Aktobe, Akmola and Almaty in Kazakhstan, and Arkhangai, Tov and Dornod in Mongolia. Overall, the selected provinces in Kazakhstan are larger in size than those in Mongolia (Fig. 1). Aktobe is the largest among the six provinces (301,697 km2), and the smallest one is Arkhangai (54,952 km2). Mongolia sits on the Mongolian Plateau that has a base elevation of 800 m a.s.l. Major geomorphological features of the study provinces are provided in Table 1. Other comparisons of the states and changes in basic biophysical, social, and economic conditions of Kazakhstan and Mongolia can be found in Chen et al. (2022)11.

Spatial distribution of average ET and GPP in Kazakhstan and Mongolia in 2020. This map was generated on Google Earth Engine with the color theme stretched to two standard deviations. Gobi Desert in southwest Mongolia does not have data coverage from MODIS databases. Polygons with white lines are the six study provinces in Kazakhstan (Aktobe, Akmola, and Almaty) and Mongolia (Arkhangai, Tov and Dornod).

Downscaling ET and GPP to land cover classes

Two spatial datasets are needed to downscale the coarse resolution MODIS products (500 m) of ET and GPP to fine resolution (30 m) land cover classifications, following the linear downscaling method of Chen et al. (2019)16 (a.k.a. Dasymetric modeling approach), which has been widely used in human geography21 and landscape studies15,17,18. In brief, the cumulative ET (or GPP) of a MODIS pixel is a linear combination of the ET (or GPP) values of all land cover classes weighted by the compositional proportion (0–1) of each land cover class. This downscaling modeling approach generates one instance ET (or GPP) value for each land cover class of the study landscape. The land cover maps from Yuan et al. (2022)19 were the most recent available at the time of this study, and the maps from 2000, 2010, and 2020 are used in this study, which can be accessed upon request. MODIS ET and GPP data can be accessed through the Earth Engine Code Editor and downloaded from Earth Engine Data Catalog (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/modis).

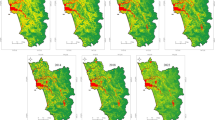

A prerequisite to applying the abovementioned downscaling approach is that the ecosystem function of any given cover class within the study landscape should be the same. One way to meet this requirement is to limit the size of the ‘landscape,’ but it would be an obvious violation if we treated each province as a whole landscape to downscale ET and GPP. In this study, we tile-cut each province into 50 × 50 km segments to serve as the landscapes (Fig. 2A). To address any mismatches between tile boundaries and provincial boundaries, titles with ≥ 80% of their area falling outside the province were excluded. Each tile has 10,000 MODIS pixels (Fig. 2B), and each MODIS pixel includes 289 Landsat pixels (Fig. 2C). For example, Dornod province ended up having 156 tiles, with 50 tiles excluded for further downscaling. The linear downscaling was independently applied for each tile to compute ET (and GPP) of each land cover type in 2000, 2010, and 2020.

Method for dividing a province into 50 × 50 km tiles for linear downscaling ET and GPP to match land cover class at 30 m resolution. (A) Example of a tile in Dornod province on a classified land cover map in 2020 (Yuan et al. 2022). (B) ET in 2020 for a demonstrative title (50 × 50 km) in Dornod. (C) Land cover map of a demonstrative MODIS pixel (500 m) showing a heterogeneous cover distribution at 30 m resolution.

There is a mismatch in temporal resolution between MODIS and Landsat datasets. MODIS ET and GPP are annually available from 2001 through 2020, whereas land cover products are for decadal periods during 2000–2020 (i.e., no annual land cover maps are available). We generated pseudo annual land cover maps by duplicating decadal year land cover maps. For example, land cover maps for years 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011 are treated as the one for 2010. This approach is premised on the assumption that LCC is expected to be negligible over a 5-year period, and the decadal land cover map was classified based on a temporal composite of images from 1–2 years (Yuan et al. 2022). Consequently, the pseudo land cover maps for 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005 were used for 2000. Similarly, land cover maps for 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 were used for 2020.

Computation methods

Another prerequisite to the downscaling method is that land cover class should be more or less equal in a landscape16. If one land cover type dominates a landscape, the linear downscaling method may not be converge as the model needs presence of all cover classes11. In Mongolia and Kazakhstan, the grassland class often dominates the landscapes19,22,23, as is illustrated in extreme cases such as Dornod, where grasslands make up > 90% and barrens < 10%. Such a grassland monopoly becomes even more prominent when a landscape is divided into small tiles and the grassland class occasionally gets as high as 95%. It clearly violates the assumption of linear downscaling method that land cover classes should be equally represented in a landscape. The solution for this is to lump rare land cover classes into the dominant land cover class to meet the requirements. A rare land cover class is operationally defined as a class whose proportion is < 5% of a MODIS pixel, whereas a dominant land cover class is defined as > 70%. In most cases in our study landscape where classes were combined, barren is the rare cover class, and it is merged into grassland class.

The large spatial coverage (924,441 km2 in total) and the average size of provinces (283,642 km2) in this study amount to more than > 300 million Landsat pixels, requiring extreme computing power. For this we accessed the High-Performance Computing Center (HPCC) of the Institute for Cyber-Enabled Research at Michigan State University. All spatial analyses were performed in R on HPCC. Data preparation began with aligning pixels from two different coordinate systems. The default coordinate reference system (CRS) of land cover maps from Landsat images is the geographic coordinate (WGS 84), which is different from the native sinusoidal projection MODIS ET/GPP product. Raster layers of land cover maps and MODIS products (ET and GPP) were reprojected to Asia North Albers Equal Area Conic. After the projections, four steps were followed for each pair of land cover maps and ET (or GPP). (1) A 500 × 500 m grid represents MODIS pixel was generated based on the geographic extent of a province “sf” package in R. These were overlaid on top of land cover maps that were extract land cover compositions for each MODIS grid using “exactextract” package in R24. (2) MODIS grids were overlaid on MODIS ET/GPP products to extract ET (or GPP) values for each MODIS grid using “exact_extract”. (3) A 50 × 50 km grid layer (i.e., tile) was generated for each province and spatially joined to the MODIS grid layer to create a foreign key table where the results from step 1 and step 2 were joined. (4) The linear regression model was fit between land cover composition and ET (or GPP) for each tile by province, country and year. R Packages, including “parallel”, “doParallel”25, “doSNOW”26, and “foreach”27 were loaded to set up the parallel computing environment on HPCC for steps 1 through 3. The computing time was 6 h on HPCC for one variable for Almaty, compared with 7 days when using ArcGIS on a personal computer. Downscaled ET and GPP were tallied by land cover class, period, and province. Descriptive statistics were also generated for each country to visualize the distribution of downscaled ET and GPP for the three periods.

Disproportional changes in landscape composition and function

Based on downscaled ET and GPP, we first calculated the functional contribution by land cover class at provincial scale: functional proportion of a land cover class in a province to its composition proportion (F/C). To understand the importance of land cover change (ΔC) in affecting functional changes (ΔF) between the consequent decades, we also calculated ΔF/ΔC. A simple linear regression model with zero intercept (F = β * C) was used to explore the relationship between land cover composition and function (ET and GPP) to test the first hypothesis. The slope mean (β0) and its standard error were used to construct 95% confidence intervals (CI) for comparisons by land cover class, province, country, and decade using “broom”, “purr”28, “tidyr”29, “ggplot2”30 and “ggpubr”31 in R. The second metric (ΔF/ΔC) between the two decadal years (i.e., from 2000 to 2010 and from 2010 to 2020) reflects the functional change enumerating the difference in ET (or GPP) as a result of land cover change between the two periods. ΔC and ΔF were first quantified by land cover class, and each time step at the 50-km tile before the mean and standard deviations of ET and GPP were tabulated at the provincial and country level.

Results

Downscaled ET and GPP

Downscaled ET and GPP of the five land cover classes were produced by the three study times and for the six provinces in Kazakhstan and Mongolia (Tables 2 and 3; Figs. 3 and 4). Among the land cover classes in Kazakhstan, the overall mean ET and GPP were lowest for barrens (82.25 mm year−1 and 170.50 gC m−2 year−1, respectively) and highest for forests (333.29 mm year−1 and 635.30 gC m−2 year−1, respectively). Cropland and grassland classes have similar mean ET and GPP, with slightly higher values in the cropland class. Similar differences by land cover classes exist in Mongolia, although both ET and GPP of all land cover classes in Mongolia are larger than those in Kazakhstan, except forest class where ETMG (312.85 ± 62.44) is lower than ETKZ (333.29 ± 94.23), and GPPMG (595.14 ± 110.94) is lower than GPPKZ (678.84 ± 242.47). However, standard deviations of ET and GPP are large, resulting in insignificant differences. Within a country, downscaled ET and GPP differ significantly among the provinces. In Kazakhstan, Akmola has the highest ET and GPP in barren, cropland, forest, and grassland classes but not in water class where Almaty edges over Akmola. In Mongolia, Tov has the highest ET in barren and water classes and Dornod has the highest ET and GPP in cropland and forest classes. Interestingly, the variances of ET and GPP in the water class are high in both countries, particularly for Almaty and Tov provinces at 164.78 ± 131.61 mm year−1 and 290.69 ± 120.74 mm, respectively. It is also worth noting that the data suggests some trends in ET and GPP during the three decades. A pairwise t-test of ET and GPP by year indicates that 2010 is statistically different from 2000 and 2020.

Boxplot of downscaled evapotranspiration (ET, mm year⁻1) and gross primary production (GPP, gC m⁻2 year⁻1) by land cover class in the three study provinces of Kazakhstan for 2000, 2010, and 2020. This panel consists of two rows and five columns of boxplots. The five columns correspond to different land cover classes, while the two rows represent downscaled evapotranspiration (ET, mm year⁻1) and gross primary production (GPP, gC m⁻2 year⁻1). For each boxplot, the x-axis displays three decades: 2000, 2010, and 2020. Each boxplot represents data for the three study provinces in Kazakhstan (Aktobe, Akmola, and Almaty from left to right), with the data points representing downscaled ET/GPP values for 50 × 50 km landscape tiles within each province. Outliers, identified using the interquartile range (IQR) criterion, are indicated by red star symbols.

Boxplot of downscaled evapotranspiration (ET, mm year⁻1) and gross primary production (GPP, gC m⁻2 year⁻1) by land cover class in the three study provinces of Mongolia for 2000, 2010, and 2020. This panel consists of two rows and five columns of boxplots. The five columns correspond to different land cover classes, while the two rows represent downscaled evapotranspiration (ET, mm year⁻1) and gross primary production (GPP, gC m⁻2 year⁻1). For each boxplot, the x-axis displays three decades: 2000, 2010, and 2020. Each boxplot represents data for the three study provinces in Mongolia (Arkhangai, Tov and Dornod from left to right), with the data points representing downscaled ET/GPP values for 50 × 50 km landscape tiles within each province. Outliers, identified using the interquartile range (IQR) criterion, are indicated by red star symbols.

Function to composition ratio (F/C)

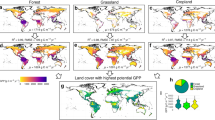

Our first hypothesis—a positive causal relationship between ecosystem functional contribution and compositional amount—is supported for landscapes in Kazakhstan and Mongolia (Fig. 5). However, these positive relationships vary by land cover class for ET and GPP at the national (Fig. 5) and provincial levels (Figs. S1 and S2). At the national level, ET and GPP of the forest class are clearly above the overall mean (i.e., the 1:1 line) albeit within the 2:1 ratio (Fig. 5). The regression slopes (β0) of ET/C and GPP/C of forest are 1.086 (± 0.005) and 1.123 (± 0.006), respectively (Table S1), indicating that the contributions of the forests to the landscape was 8.6% and 12.3% of the landscape average ET and GPP, respectively. Interestingly, ET/C and GPP/C of the grassland and cropland classes have β0 near the 1:1 line, although estimated mean (CI) β0 are < 1 (0.988 ± 0.004 for cropland ET; 0.982 ± 0.004 for cropland GPP; 0.993 ± 0.003 for grassland ET; and 0.994 ± 0.002 for grassland GPP) (Table S2). The β0 of regression lines for ET and GPP of the barren class are much lower than 1 but greater than zero (0.941 ± 0.015 for ET and 0.809 ± 0.013 for GPP). Estimated β0 of ET and GPP for water is 0.971 ± 0.008 and 0.949 ± 0.007, respectively.

(A) Changes in ET and GPP with landscape composition by land cover class of the six study provinces. (B) Slope and confidence interval (CI) of fitted linear regression lines in A. See Table S1 for slope and CI values by cover type and province. The solid lines denote a ratio of 1:1, the dotted line indicates a ratio of 1:2, and the dashed line refers to a ratio of 2:1.

At the provincial level, similar causal relationships by land cover class exist but with some degrees of differences by province (Figure S1 and S2). For three provinces in Kazakhstan, β0 of forest ET and GPP are all > 1. β0 for GPP of Aktobe and Akmola are 1.510 ± 0.014 and 1.513 ± 0.012, respectively, compared with 1.108 ± 0.015 for Almaty. Similar differences exist for β0 values among the three provinces. For the grassland class, β0 of GPP in Aktobe and Akmola are 1.013 ± 0.004 and 1.016 ± 0.006, respectively, whereas in Almaty it is 0.968 ± 0.005. β0 of grassland ET in the three provinces show similar contrasts: 1.009 ± 0.004 for Aktobe, 1.009 ± 0.007 for Akmola, and 0.964 ± 0.006 for Almaty. Interestingly, β0 for cropland GPP β0 in Aktobe and Akmola is slightly smaller than 1, but it is greater than 1 in Almaty (1.048 ± 0.018). β0 for cropland ET in Aktobe is > 1 but < 1 in Akmola and Almaty. As expected, β0 for ET and GPP for barren class are always < 1. Large differences in β0 for ET of the water class are observed among the three provinces, with 0.008 ± 0.005 for Aktobe, 1.028 ± 0.010 for Almaty, and 0.765 ± 0.017 for Akmola. β0 for GPP of water mirror the pattern found in ET, which 0.129 ± 0.017 for Aktobe, 0.999 ± 0.008 for Almaty, and 0.688 ± 0.015 for Akmola. For provinces in Mongolia, β0 of forest ET and GPP are all > 1; near 1 for grassland but < 1 for cropland and barren. β0 of cropland ET and GPP of Akhangai are smaller than that of Tov and Dornod.

ΔFunction/Δcomposition

Our second hypothesis is also supported, albeit with large differences by land cover class and landscape, suggesting that the changes in landscape ET over the 30-year study period are not caused equally by the changes in land cover class (Fig. 6, Figs. S3 and S4). At the national level, ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC of the forest and cropland classes are negative, while those of the grassland and barren classes are positive. For the water class, mean ΔET/ΔC is negative but mean ΔGPP/ΔC is positive. Mean ΔF/ΔC of a province does not always agree with that of the country. Cropland in Arkhangai has positive mean ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC; these values are negative in other two provinces in Mongolia. The mean grassland ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC in Aktobe and Akmola are negative but positive in Almaty. For water class in Tov and Dornod, mean ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC are negative, but they are positive in Arkhangai. Barren class has positive ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC across all provinces.

Discussion

Downscaled ET and GPP in Kazakhstan and Mongolia

Through downscaling MODIS ET and GPP at a coarse resolution of 500 m we produced landscape (i.e., tile) and province ET and GP by land cover class for three periods in six provinces of Kazakhstan and Mongolia. This an essential task for understanding the spatial and temporal changes in ecosystem functions during land cover change where the patch size is often smaller than MODIS resolution. Otherwise, one cannot pin the magnitude and dynamics of change for any land cover patch in a landscape. Because our downscaling is based on MODIS products, ET and GPP values for the provinces and landscapes should match well with other values using MODIS reported in the literature32. In the most recent report on MODIS GPP and ET for these two countries, Chen et al. (2020)10 estimated the average GPP in Kazakhstan and Mongolia is 225.9 gC m−2 year−1 and 181.9 gC m−2 year−1, respectively. These national averages of GPP are at the lower end of our study-area estimates, ranging 170.50–635.20 gC m−2 year−1 for Kazakhstan and 176.08 181.9–595.14 181.9 gC m−2 year−1 for Mongolia. This is likely because the six provinces included in this study are dominated by grasslands, while other provinces in these countries include desert biomes that have substantially lower GPP and ET. Similarly, the ET estimate by Chen et al. (2020)10 is 182 mm year−1 for Kazakhstan and 259 mm year−1 for Mongolia, while our ET estimate is 82.45–333.29 mm year−1 for Kazakhstan and 127.86–312.85 mm year−1 for Mongolia. In another study on GPP using a light use efficiency model in Kazakhstan, Propastin and Kappas (2012)33 reported a steppe grassland GPP of 243.70 (± 59.50) gC m−2 year−1, which is close to our estimate of 254.13 (± 101.97) gC m−2 year−1. Liu et al. (2013)34 reported ET of three land cover classes on the Mongolian Plateau using a process-based model, including grassland (242–374 mm year−1), boreal forest (213–278 mm year−1) and semi-desert/desert (100–199 mm year−1). The corresponding estimates for these land cover classes in our study are 204.74 (± 53.94) mm year−1, 312.85 (± 49.43) mm year−1, and 127.86 (± 45.95) mm year−1, respectively, which are within the ranges modeled values. However, it is worth noting that drought, which can reduce GPP, is often underestimated by remote sensing methods35. In Kazakhstan and Mongolia, where arid landscapes are under constant threat of water deficit and warmer and drier trends are predicted due to global climate change, drought can also lead to decreases in GPP36, suggesting that our GPP values are likely underestimated.

This study presents a highly effective approach that is applicable not only to Asian drylands but also to global investigations of land cover and land cover changes, focusing on differences in carbon production, ET, water use efficiency, and other ecosystem functions at high spatial resolution under varying climate gradients and scenarios. A substantial body of literature supports our findings using alternative methods such as remote sensing modeling and field observations5,37,38. These recent studies serve as examples for interested readers.

We advocate for applying this innovative method to ecosystems beyond arid and semi-arid regions, extending to non-water-constrained ecosystems in the future. Additionally, we acknowledge the importance of understanding the mechanisms or drivers on ecosystem functional changes resulting from land use and cover change (LULCC). However, this study focuses primarily on developing computationally efficient approaches and rapid assessment tools/metrics for evaluating the impact of LULCC on ecosystem functions.

Disproportionate contributions of land cover and changes to ecosystem functions

Disproportionate functional contribution to compositional makeup of various land cover classes have been intensively studied at plot-to-ecosystem scale. We designed our research to quantify this asymmetrical functional-to-compositional association by land cover class at landscape scale, which provides a unique perspective for understanding the changing landscape. The slopes of linear regression for F/C can be interpreted as practical and operational terms: a unit area of forest generates 1.085 unit of ET and 1.123 unit of GPP, a unit area of grassland generates 0.993 unit of ET and GPP, a unit area of cropland produces 0.987 unit of ET and 0.983 unit of GPP, a unit area of water produces 0.949 unit of GPP and 0.971 unit of ET, a unit area of barren generates 0.941 unit of ET and 0.809 unit of GPP (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we found that not all land cover classes have functions proportionate to their compositional shares. Grassland and cropland classes have ecosystem functions approximately commensurate to their size, whereas forest, barren and water classes have asymmetrical F/C with opposite directions: forest’s functional contribution is larger than its area, while barren and water land cover have functional contributions smaller than their compositional amounts. The 1:1 line can be considered the equal contribution line, which means a unit of land cover generates a unit of ecosystem function measured by ET or GPP. A land cover class near this line (e.g., the grassland and cropland) is considered average performance, whereas F/C = 2:1 is making a double contribution, i.e., a unit of land cover generates 2 units of ecosystem function. Importantly, the land cover classes above the 1:1 line contribute more functions to the landscape total; forest and sometimes water (depending on whether the water class is dominated by wetlands or open water) belong to this group. Similarly, the 1:2 line indicates a half contribution, i.e., a unit of land cover generates 0.5 unit of ecosystem function. The barren land cover class clearly belongs to this group.

The divergent F/C among land cover classes further accounts for ΔF/ΔC—an indicator of functional changes during land cover change. For example, where the F/C forests is the highest among the five classes, mean ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC are always negative across the provinces in both countries (Table 4), indicating that converting a unit of forest to another land cover class will lead to a 0.67 unit decrease in ET and a 0.6 unit decrease in GPP. Conversely, the ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC values of the barren class are greater than one, meaning that converting a unit of barren land cover to another land cover class will lead to a 0.3 unit increase in ET and a 0.28 unit increase in GPP, partially because F/C of the barren class is the lowest among the five land cover classes. In Mongolia, removal of a unit area of cropland will cause a 0.12 unit decrease in ET and a 0.11 decrease in GPP (Table 4). Losing a unit area of grassland will increase ET by 0.14 and GPP by 0.05 unit. Interestingly, in Kazakhstan ΔF/ΔC of grasslands and croplands varied among the provinces. ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC of grasslands are less than zero, except in Almaty, while in Mongolia grassland F/C is invariably above zero. ΔET/ΔC of croplands is above zero in Arkhangai and below zero in Aktobe and Akmola. Conversely, ΔF/ΔC of the grassland is below zero in Arkhangai and above in the other two provinces.

Utility of F/C and ΔF/ΔC metrics

The utility of downscaled ET and GPP is that it allows us to connect the functional changes of ecosystems to the compositional changes of landscapes during LULCC. With the development of fine resolution land cover products worldwide, our downscaling method can be applied to produce corresponding resolution ecosystem function measurements, such as ET and GPP. This rapid assessment tool will potentially become more useful for evaluating the impacts of LULCC on ecosystem functions than in-situ field-based method. Facing a growing global demand for food and fiber, certain types of land use and land cover conversions (e. g. deforestation, afforestation, reclamation, cropland abandonment, etc.) will likely expand. The consequences for water and carbon budgets beyond the ET and GPP we examined should be considered for land use planning when decision-making, especially in light of increasing frequency and intensity of climate extremes.

For example, Kazakhstan and Mongolia experienced extensive LULCC in the mid-twentieth century, through the virgin land campaign in Kazakhstan in the 1950s and through Atar Ezemshik I in Mongolia in the 1940s. If we use our proposed metrics F/C as a quick reference to calculate this impacts of land use land cover change on ecosystem function , the conversion of 5522 km2 of grassland to cropland from 1990 to 2000 in Tov19 would result in an increase of 1.45 × 108 m3 year−1 water evaporated to air (cropland ET/C − grassland ET/C × ΔArea = [(158.67 − 132.39) mm year−1 × 10–3 m × 5522 km2 × 106 m2] ≈ 1.45 × 108 m3 year−1) and gaining carbon 4.12 × 1011 g C m−2 year−1 ((cropland GPP/C − grassland GPP/C) × ΔArea = [(300.30 − 225.70) gC m−2 year−1 × 5522 km2 × 106 m2] ≈ 4.12 × 1011 g C m−2 year−1). In another words, this type of conversion would save 1.45 × 108 m3 of water per year via ET reduction but result in loss of 4.12 × 1011 g C carbon production per year excluding all other factors affecting the water and carbon cycles. Another LULCC scenario emerging on the Mongolia Plateau is the conversion of native steppe to forest under the Three-North Shelter Forest of China—an afforestation program that converted 1.64 million ha grassland to forest in northern China between 1990 and 200539. Our proposed metrics ΔF/ΔC serves a handy calculator to assess the impact of this type of land conversion on the ecosystem function. Grassland ΔET/ΔC is positive, meaning that conversion of grassland to another land cover results in an increase of 1219 m3 ET over a decade, while gaining 4.43 × 106 g C over a decade. In other words, this type of conversion would lead to a 1219 m3 water deficit. Contextualizing these types of land use conversions in semi-arid/arid environments where water resources are scarce illustrates the outsized impact of directional LULCC and the need for caution as well as scientific investigation in environmental planning and decision-making. Our proposed metrics can be utilized as a rapid assessment tool to weigh costs and benefits in the context of landscape scale ecosystem function and services.

Uncertainties

We are aware of several major drawbacks in estimating high resolution ET and GPP by land cover class. The first issue is associated with the sample design. We generated 50 km × 50 km tiles as the landscape for downscaling—an assumption for the method16. This tile size is obviously arbitrary and may need adjustment according to the size of provinces. Our aim in selecting this size was to establish an analysis unit that represented the whole landscape in theory and, at the same time, was easy to convert in practice in the downscaling method. We ended up multiplying the pixel size of ET and GPP products from MODIS (500 × 500 m) by 100 as our spatial unit. This tiling approach can occasional fragment the study landscape, albeit serving our purpose. Nevertheless, we propose that future research should address this issue and optimize the spatial sampling unit. Performing a sensitivity analysis would likely be helpful and informative to test how landscape properties (i.e., patch composition, configuration, and connectivity etc.) change in response to a varying tile size. Another concern is that climate trends have not been taken into consideration. We compiled ET and GPP from 2001 to 2015 and pooled them to match the decadal years of land cover maps. We found that decadal year 2000 and 2020 products have similar ET and GPP values. However, we propose using advanced statistics to de-trend ET and GPP datasets in the future. More importantly, we are not measuring ET and GPP changes as a result of LULCC but providing a landscape scale method to estimate ET and GPP by land cover class, and ultimately this method can serve as a rapid assessment to quantify potential causes of LULCC for ET and GPP. Another hoped-for improvement for future research would be the production of a finer thematic resolution land cover product. The water land cover class could be improved with more specific classification, such as wetland and open water, and forest could also be further divided into coniferous and deciduous forests (both are common in Kazakhstan and Mongolia).

Conclusion

Linear downscaled ecosystem measurement by land cover change product reflects the ecosystem properties in this arid/semi-arid region and reveals the distinctness in ET/GPP by land cover class. Land cover types have signature ecosystem ET and GPP, and their values vary within and between countries. This landscape scale evaluation of ecosystem function provides a unique perspective for understanding the consequences of LULCC on ecosystem water cycle and carbon budget at the macrosystem level. The spatial resolution of our method (30 m) establishes a link between MODIS products (500 m) and land cover products (30 m), which are widely but separately used to assess landscape scale LULCC. By establishing two metrics—function to composition ratio (F/C) and changes in function to changes in composition (ΔF/ΔC)—our hypothesis that a landscape’s function measured by ET and GPP is disproportionate to its composition was tested and supported. The slopes of linear regressions for F/C can be interpretated in practical and operational terms as: a unit area of forest generates 1.085 unit of ET and 1.123 unit of GPP, a unit area of grassland generates 0.993 unit of ET and GPP, a unit area of cropland produces 0.987 unit of ET and 0.983 unit of GPP, a unit area of water produces 0.949 unit of GPP and 0.971 unit of ET, and a unit area of barren generates 0.941 unit of ET and 0.809 unit of GPP. In addition, the hypothesis that changes in land cover composition will have asymmetrical impacts on a landscape’s functioning was also supported. The divergent F/C among land cover classes further accounted for ΔF/ΔC—an indicator of functional changes during land cover change. ΔET/ΔC and ΔGPP/ΔC of forest and cropland class have negative values, and grassland and barren have positive values, indicating that conversion of a unit of forest to another land cover leads to a 0.67 unit decrease in ET and a 0.6 unit decrease in GPP, but conversion of a unit of grassland or barren to another land cover classes results in an increase in ET and GPP. The utility of this linear downscaling approach in macroecology and two metrics F/C and ΔF/ΔC is that it is a labor-saving and cost-effective approach and provides a rapid assessment for the impact of LULCC on ecosystem functions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Luyssaert, S. et al. Land management and land-cover change have impacts of similar magnitude on surface temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 389–393 (2014).

Powers, R. P. & Jetz, W. Global habitat loss and extinction risk of terrestrial vertebrates under future land-use-change scenarios. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 323–329 (2019).

Pielke, R. A. et al. Land use/land cover changes and climate: Modeling analysis and observational evidence. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2, 828–850 (2011).

Mahmood, R. et al. Land cover changes and their biogeophysical effects on climate. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 929–953 (2014).

Chen, J., North, M. & Franklin, J. F. The contributions of microclimatic information in advancing ecosystem science. Agric. For. Meteorol. 355, 110105 (2024).

Lambin, E. F. et al. The causes of land-use and land-cover change: Moving beyond the myths. Glob. Environ. Change 11, 261–269 (2001).

Lambin, E. F. & Meyfroidt, P. Global land use change, economic globalization, and the looming land scarcity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 3465–3472 (2011).

Goldewijk, K. K., Beusen, A., Doelman, J. & Stehfest, E. Anthropogenic land use estimates for the Holocene-HYDE 3.2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 927–953 (2017).

Technical Summary—Special Report on Climate Change and Land. https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/technical-summary/.

Gutman, G., Chen, J., Henebry, G. M. & Kappas, M. Landscape Dynamics of Drylands Across Greater Central Asia: People, Societies and Ecosystems. Vol. 17 (Springer, 2020).

Chen, J. et al. Sustainability challenges for the social-environmental systems across the Asian Drylands Belt. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 023001 (2022).

Potapov, P. et al. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00429-z (2021).

Potapov, P. et al. The global 2000–2020 land cover and land use change dataset derived from the landsat archive: First results. Front. Remote Sens. 3, 18 (2022).

Wulder, M. A., Masek, J. G., Cohen, W. B., Loveland, T. R. & Woodcock, C. E. Opening the archive: How free data has enabled the science and monitoring promise of Landsat. Remote Sens. Environ. 122, 2–10 (2012).

Shakya, A. K., Ramola, A. & Vidyarthi, A. Statistical quantification of texture visual features for pattern recognition by analyzing pre- and post-multispectral landsat satellite imagery. Nat. Hazards Rev. 22, 05021011 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Linear downscaling from MODIS to landsat: Connecting landscape composition with ecosystem functions. Landsc. Ecol. 34, 2917–2934 (2019).

Sciusco, P. et al. Albedo-induced global warming impact at multiple temporal scales within an Upper Midwest USA watershed. Land 11, 283 (2022).

Shirkey, G. et al. Fine resolution remote sensing spectra improves estimates of gross primary production of croplands. Agric. For. Meteorol. 326, 109175 (2022).

Yuan, J. et al. Land use hotspots of the two largest landlocked countries: Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Remote Sens. 14, 1805 (2022).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on Earth: A new global map of terrestrial ecoregions provides an innovative tool for conserving biodiversity. Bioscience 51, 933–938 (2001).

Nagle, N. N., Buttenfield, B. P., Leyk, S. & Spielman, S. Dasymetric modeling and uncertainty. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 104, 80–95 (2014).

Venkatesh, K. et al. Untangling the impacts of socioeconomic and climatic changes on vegetation greenness and productivity in Kazakhstan. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 095007 (2022).

Venkatesh, K. et al. Optimal ranges of social-environmental drivers and their impacts on vegetation dynamics in Kazakhstan. Sci. Total Environ. 847, 157562 (2022).

Baston, D. exactextractr: Fast Extraction from Raster Datasets Using Polygons. R Package Version 0.7.0 (2021).

Weston, S. doParallel: For Each Parallel Adaptor for the ‘Parallel’ Package (2022).

Weston, S. doSNOW: Foreach Parallel Adaptor for the ‘Snow’ Package (2022).

Weston, S. foreach: Provides Foreach Looping Construct (2022).

Wickham, H. & Henry, L. purrr: Functional Programming Tools (2023).

Wickham, H., Vaughan, D. & Girlich, M. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data (2023).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Use R! (Springer, 2016).

Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots (2023).

John, R. et al. Modelling gross primary production in semi-arid Inner Mongolia using MODIS imagery and eddy covariance data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 34, 2829–2857 (2013).

Propastin, P. A., Kappas, M. W., Herrmann, S. M. & Tucker, C. J. Modified light use efficiency model for assessment of carbon sequestration in grasslands of Kazakhstan: Combining ground biomass data and remote-sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 33, 1465–1487 (2012).

Liu, Y. et al. Response of evapotranspiration and water availability to changing climate and land cover on the Mongolian Plateau during the 21st century. Glob. Planet. Change 108, 85–99 (2013).

Stocker, B. D. et al. Drought impacts on terrestrial primary production underestimated by satellite monitoring. Nat. Geosci. 12, 264–270 (2019).

Wei, X. et al. Global assessment of lagged and cumulative effects of drought on grassland gross primary production. Ecol. Indic. 136, 45 (2022).

Yao, J. et al. Accelerated dryland expansion regulates future variability in dryland gross primary production. Nat. Commun. 11, 1665 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Regular and irregular vegetation pattern formation in semiarid regions: A study on discrete Klausmeier model. Complexity 2020, 54 (2020).

He, B., Miao, L., Cui, X. & Wu, Z. Carbon sequestration from China’s afforestation projects. Environ. Earth Sci. 74, 5491–5499 (2015).

Funding

This study was supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Grant No. 80NSSC20K0410).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. and J.C both contribute to manuscript writing and data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, J., Chen, J. Disproportionate contributions of land cover and changes to ecosystem functions in Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Sci Rep 14, 21922 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72231-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72231-3