Abstract

The rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has triggered global difficulties for both individuals and economies, with new variants continuing to emerge. The Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 remains most prevalent worldwide, and it affects the efficacy of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination. Expedited testing to detect the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 and monitor viral transmission is necessary. This study aimed to develop and evaluate a colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) technique targeting the L452R mutation in the S gene for the specific detection of the Delta variant. In the test, positivity was indicated as a color change from purple to yellow. The assay’s 95% limit of detection was 57 copies per reaction for the L452R (U1355G)-specific standard plasmid. Using 126 clinical samples, our assay displayed 100% specificity, 97.06% sensitivity, and 98.41% accuracy in identifying the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 compared to real-time RT-PCR. To our knowledge, this is the first colorimetric RT-LAMP assay that can differentiate the Delta variant from its generic SARS-CoV-2, enabling it as an approach for studying COVID-19 demography and facilitating proper effective control measure establishment to fight against the reemerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 was discovered in China in December 2019, and it quickly spread globally, presenting significant challenges to public health and economies. The virus continues to spread, new variants have continually emerged1,2,3. At present, five dominant SARS-CoV-2 variants are circulating globally, namely the Alpha (B.1.1.7, formerly known as the UK variant), Beta (B.1.351, formerly known as the South Africa variant), Gamma (P.1, formerly known as the Brazil variant), Delta (B.1.617.2, formerly known as the India variant), and Omicron (B.1.1.529). The latter of which had spread to 57 countries4,5,6.

The receptor-binding domain (RBD) has been mutated in several SARS-CoV-2 variants, increasing their binding capacity for human cell receptors. A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) from U to G at nucleotide position 1355 (U1355G) in the S gene results in an amino acid change from leucine to arginine (L452R) in the spike protein. This mutation has been observed in the Delta variant (B.1.617.2)7. This mutation might provide competitive advantages over other variants. Mutation of the spike protein at residue 452 in the RBD could enhance immune evasion and resistance to antibody neutralization. All of these alterations might lead to an increase in ACE2 receptor affinity and resistance to antibody neutralization, which would boost transmissibility8,9. Scientists have officially proven that the presence of one specific change, namely L452R, in the RBD region of the Delta variant significantly increases its ability to spread and infect humans, resulting in significantly more severe cases of morbidity and mortality compared to the findings for the other SARS-CoV-2 variants10,11,12,13.

Obviously, SNPs represent the most common type of genetic variation found in individuals, and they have strong influences on human diseases14. Regarding SARS-CoV-2, the variant of concern- and variant being monitored-specific amino acid substitutions, especially those in the Delta variant, can be identified using a specific RT-PCR assay targeting SNPs15. For example, a diagnostic kit based on RT-PCR was developed to identify the Delta variant by targeting specific mutations (P681R and L452R) in the S gene16. However, using PCR assay might pose challenges in terms of conducting tests on-site or in low-resource settings. Thus, new SNP detection techniques that can be applied rapidly without advanced laboratory tools or a refrigerated supply chain are needed. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) can be used in point-of-care settings to identify target SNPs with high specificity and sensitivity17.

LAMP permits the rapid and accurate amplification of DNA under consistent temperature settings18. It can also be used to detect viral RNA by simply adding reverse transcriptase into the reaction. Reverse-transcription (RT)-LAMP enables more rapid genetic material testing than conventional RT-PCR, and it has displayed utility in identifying COVID-1919. Various methods can confirm the results of the amplification process, such as changes in turbidity, fluorescence, pH indicators, or gel electrophoresis combined with UV detection20,21,22. A commonly used approach for identifying plant, animal, and human diseases, especially COVID-19, is a pH-based colorimetric test that delivers visible results to the naked eye19,23,24,25,26. For example, some tests use xylenol orange for visual confirmation24,27. Through developing rapid molecular diagnostic tests based on colorimetric RT-LAMP for Delta variant-specific mutations of interest, laboratories can monitor variants more rapidly and efficiently implement more focused and suitable surveillance and control programs. However, few colorimetric RT-LAMP assays have focused on SNPs. In this study, we established a probe-free colorimetric RT-LAMP assay based on the L452R mutation to detect the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2 and discriminate this variant from other variants.

Results

RT-LAMP primer set screening

For RT-LAMP to effectively serve as an isothermal amplification assay, it must be compatible with at least four primers, specifically F3, B3, forward inner primer (FIP), and BIP. Loop primers which are classified as extra primers can be used to enhance the kinetics of LAMP. This study established that the combination of FIP and loop primer forward (LPF) played a crucial role in specifically targeting the L452R (CTG to CGG) mutation on the RBD region of the S gene. FIP and LPF were meticulously optimized to directly interact with the specific site of the SNP. To examine the effect of mutations on primer sets, we conducted an in-silico analysis to assess the performance of our designed primers. We investigated primers with 0–3 nucleotide base mismatches adjacent to the specific SNP position in their sequences. These sets were termed set-0 (zero mismatch), set-1 (one mismatch), set-2 (two mismatches), and set-3 (three mismatches), as presented in Table 1. The primer sets were evaluated by empirical methods using the genomic RNA of the mutant (Delta variant) and wild-type strains (Wuhan-Hu-1) of SARS-CoV-2. The presence of signal fluorophores was observed, indicating the successful amplification of the mutant strain compared to the wild-type strain. This amplification occurred under an isothermal condition maintained at appropriate temperatures of 60 °C and 63 °C. Primer sets that specifically amplified the mutant template within the given assay time were selected to effectively amplify and differentiate the mutant and wild-type samples by monitoring the deviation in the quantitative cycle (Cq) values between the two samples.

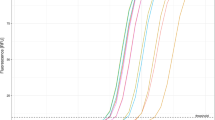

Based on our investigation, primer set-3, in which three bases neighboring the U1355G site were modified, failed to amplify the mutant or wild-type templates (Cq data unavailable). Primer set-2 generated a fluorescence signal at 60 °C, whereas no response was observed at 63 °C. Using primer set-1, a delay in the detection of Cq for the mutant template was observed on real-time fluorograms. Primer set-0, despite a noticeable delay in the reaction of the mutant template at 63 °C with a Cq of approximately 30 cycles, efficiently amplified the mutant template at an extremely rapid rate with a Cq of less than 20 cycles at 60 °C (Fig. 1). Using the real-time fluorescence signal, all different primer sets failed to amplify sequences of the wild-type strain (Wuhan-Hu-1) of SARS-CoV-2. To summarize, we selected primer set-0 for the targeted identification of U1355G (L452R) inside the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 using an isothermal condition at 60 °C.

The fluorescence signal of the real-time RT-LAMP assay was used to amplify the RNA-positive Delta variant and wild-type strain (Wuhan-Hu-1) of SARS-CoV-2. The result was achieved using four primer sets with different temperatures. (a) The temperature for real-time RT-PCR amplification was set at 60°C. (b) The temperature for real-time RT-PCR amplification was set at 63°C. The primer set-0 (zero mismatch) is indicated as a red line color. The primer set-1 (one mismatch) is indicated as a yellow line color. The primer set-2 (two mismatches) is indicated as a purple line color. The primer set-3 (three mismatches) is indicated as a light blue line color. The NTC, or negative control, is indicated as a green color, meaning that all primer sets were tested with the wild-type strain (Wuhan-Hu-1) of SARS-CoV-2.

Optimal incubation time for the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay

A colorimetric RT-LAMP assay permitting visual detection was developed to improve the convenience of the application. The response generated a distinct alteration in color, transitioning from purple to yellow, across all serial dilutions of the plasmid standard samples evaluated for 75 min. Hence, we selected 75 min as the most effective duration for the visual examination (Fig. 2a). A slight color shift was observed after incubating 500 copies of the plasmid standard for 60 min. Unexpectedly, after 40 min, the color was an intermediate shade that closely resembled a negative outcome across all serial dilutions. These results suggest that the colorimetric reaction system achieves excellent visual detection with incubation for 75 min for the RT-LAMP assay.

The performance of the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay. (a) Optimal incubation time at 60 °C used serial dilutions of the plasmid standard including 50, 500, 5000, 50,000, and 500,000 copies per reaction for 40, 60, and 75-min time points. The results provide excellent visual detection within a 75-min incubation period for RT-LAMP. (b) The analytical sensitivity assay using the L452R-specific plasmid standard that was diluted in a series had a range of 0–1000 copies per reaction. The LoD was demonstrated to be 100 and 50 copies per reaction, with a positive rate of 100% and 90%, respectively. These results were used to calculate the LoD95 to improve the analytical sensitivity, which was determined to be 57.00 copies per reaction using Probit regression analysis using Analyse-it software. (c) The analytical specificity assay used a plasmid standard and a sample group of genomic RNA samples, including human coronavirus (HCoV-229E), IAV subtype H3N2, IBV, Victoria lineage, and RSV. Furthermore, there are additional viruses, including PEDV, HAV, EV71, HSV, DENV1-4, ZIKV, CHIKV, and JEV. PC: Positive control (L452R-specific plasmid standard); NC: Negative control (DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water).

Analytical sensitivity and specificity

The analytical sensitivity of the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay was determined using various dilutions of the plasmid standard featuring the targeted L452R substitution in the RBD region of SARS-CoV-2. These dilutions included 0, 25, 50, 100, 500, and 1000 copies per reaction, and each dilution was tested in 10 replicates. When the concentration exceeded 100 copies of the plasmid standard, all 10 reactions (100%) exhibited a positive result, as illustrated by a color change from purple to yellow. With concentrations of 25 and 50 copies of the plasmid standard, three and nine replicates, respectively, exhibited positive results (Fig. 2b). Probit analysis was used to compute the 95% limit of detection (LoD95) by determining the hit rate. The LoD95 was determined to be 57.00 copies per reaction (95% confidence interval [CI] 36.11–89.98%).

The analytical specificity of the assay was investigated by applying a plasmid standard and genomic RNA samples from various viruses, including the wild-type strain and Alpha variant (B.1.1.7) of SARS-CoV-2, human coronavirus (HCoV-229E), influenza A virus (IAV) subtype H3N2, influenza B virus (IBV, Victoria lineage), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), hepatitis A virus (HAV), enterovirus 71 (EV71), herpes simplex virus (HSV), dengue virus 1–4 (DENV1–4), Zika virus (ZIKV), Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV). The specificity tests revealed no amplification or any change in color for any of the 14 viruses after 75 min of incubation. This indicates that the assay has excellent specificity and the ability to accurately identify the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2 without any cross-reactivity (Fig. 2c).

Clinical sample evaluation

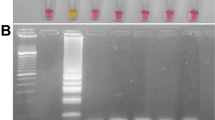

A colorimetric RT-LAMP assay was developed to detect the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2. The assay was clinically evaluated and compared with a commercial real-time RT-PCR assay, which is considered the gold standard. In total, 126 clinical samples were evaluated. These samples included both suspected cases of the Delta variant (positive population) and a control population that tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Table 2 reveals that of the 68 samples identified as positive by real-time RT-PCR, 66 tested positive by colorimetric RT-LAMP. In addition, all 58 samples that were previously identified as negative using real-timeRT-PCR were similarly negative using colorimetric RT-LAMP. Furthermore, an evaluation of this assay in a representative group of patients revealed both positive and negative outcomes, as represented by a yellow and purple color, respectively. In addition, we examined the visual results by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). Some Delta variant-positive samples (D1–30) exhibited false-negative results (indicated by purple color), and the amplification product was not visible on gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3a). Conversely, certain negative samples (H1–30) displayed true-negative results (indicated by purple color), and the amplification product was not visible on gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3b).

Evaluation of representative clinical samples using the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay. The yellow color indicates a positive readout. The purple color indicates a negative one. Then, the RT-LAMP amplification products were observed on a 2%-agarose gel electrophoresis analysis. (a) The positive clinical sample results for the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 (D1–30) are represented by numbers 1–30. (b) The negative clinical sample results of SARS-CoV-2 (H1–30) are represented by numbers 1–30. P: Positive control (L452R-specific plasmid standard); N: Negative control (DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water); L: 100 bp DNA ladder. The gel electrophoresis image was cropped to emphasize only the samples loaded in the gel, and the original gels are provided in Supplementary Figure S4–S7.

The substantial relationship between the cycle threshold (CT) values and the results obtained using the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay indicates the reliable capacity of this method to consistently identify viral loads lower than 38. Nevertheless, false negatives can occur in samples with CT values higher than 38, suggesting that the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay could lack the ability to identify viral loads below a certain threshold among those samples.

In a comparison of colorimetric RT-LAMP and real-time RT-PCR, the developed colorimetric assay had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100.00% (95% CI 94.56–100.00). In addition, RT-LAMP had a negative predictive value (NPV) of 96.67% (95% CI 88.10–99.13). The obtained results illustrated that the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay had a clinical sensitivity of 97.06% (95% 89.78–99.64), a clinical specificity of 100.00% (95% CI 93.84–100.00), and a clinical accuracy of 98.41% (95% CI 94.38–99.81). These findings indicate the outstanding consistency between the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay and real-time RT-PCR.

Discussion

LAMP-based technologies are commonly used as substitutes for traditional techniques to detect SNPs and identify pathogens28. In the present study, we first examined the effectiveness of colorimetric RT-LAMP in detecting the globally widespread Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, which is identified by the L452R SNP mutation in the RBD of the spike protein. Our research endorses previous studies which suggests that RT-LAMP could potentially serve as a rapid and cost-efficient diagnostic method for detecting SARS-CoV-229,30,31,32,33 and identifying the Delta variant34,35.

We picked the characteristic mutation L452R in the S gene as the focus of our study, as it is associated with the Delta variant (B.1.617.2). The L452R mutation can potentially enhance transmissibility and reduce susceptibility to existing vaccines7. This study revealed that the optimal incubation time for colorimetric RT-LAMP testing was 75 min, as it was capable of accurately detecting the plasmid standard with a minimum of 50 copies per reaction. In comparison, at 60 min, the assay could identify a positive color with up to 5,000 copies. Increasing the reaction time beyond 60 min thus enhanced the sensitivity of the test. The LAMP approach has been utilized in previous research to identify different viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2. The entire procedure is usually finished after 30–60 min of incubation at a consistent temperature of 60–68 °C18,36,37,38. However, this procedure relied on the specifically applied RT-LAMP master mix39. In this study, the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay was completed after 75 min of incubation at 60 °C using a plasmid-specific L452R SNP mutation as the template.

The colorimetric RT-LAMP test has high analytical sensitivity with a LoD95 of 57.00 copies per reaction, and it displayed no cross-reactivity with 14 related human respiratory and non-human respiratory viruses. Testing this assay using clinical samples exhibited exceptional effectiveness in identifying and differentiating the Delta variant in the genomic RNA. The test displayed a specificity of 100% with no false positives, a sensitivity of 97.06%, and an accuracy of 98.41%. The sensitivity, in combination with the capacity to detect low viral numbers, increases the utility of this assay for the early diagnosis of infections and efficient disease control. False negatives were reported in samples with CT values around and above 38, suggesting an issue in identifying extremely low viral loads.

Colorimetric RT-LAMP has a similar specificity and sensitivity to real-time RT-PCR assays, as demonstrated in other studies. In the example studies, Nuchnoi et al.26 and Alhamid et al.40 discovered that the RT-LAMP technique, incorporating color indication, effectively detected SARS-CoV-2 infection with sensitivities of 91.67% and 94.6%, respectively, and specificities of 100% and 92.9%, respectively.

As for the limitations, like any other pH-dependent dye-based colorimetric LAMP in principle, the intrinsic drawback of our assay is that it is unable to differentiate between target LAMP amplicons and any non-target ones that may present in the reaction mixture. This is because xylenol orange responds colorimetrically to a drop in pH of the RT-LAMP solution due to the production of hydrogen ion during any DNA amplification whether it is specific or not. However, the presence of unexpected non-specific amplification is unlikely as the primers we designed are highly specific for their target genes. Readers who would like to adopt our mismatch-LAMP-assay concept to their works are encouraged to carefully designed and experimentally validate their primers prior uses.

Regarding the advantages, our assay is better than other COVID-19 colorimetric platforms that leveraged color-changeable gold-functionalized probe-based RT-LAMP41 and CRISPR-dependent lateral flow chromatography42,43 with respect to the simplicity as our assay did not need post-amplification workflows associated with hybridization, multiple pipetting, and readout development. Thus, forward contamination can be reduced. Additional advantages over other colorimetric RT-LAMP modalities are summarized in Supplementary Table S3.

The primer sequence of the LPF primer targeting the L452R SNP mutation is present in the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) and the Omicron subvariants BA.4 and BA.544. Twenty genomic RNAs of Omicron subvariant BA.5 from clinical samples were assessed using our technique. We noticed positive outcomes in some clinical samples. Therefore, the primer set targeting L452R is effective for specifically identifying the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2. The comparison of primer sequences indicated that the colorimetric RT-LAMP method does not amplify the Omicron subvariants (BA.4 and BA.5) because of the differences in their sequences. The RT-LAMP primers were designed using GenBank accession number OP412303.1 as a prototype for the Delta variant. The five primers (B3, F3, BIP, FIP, and LPF) in Table 1 exhibited 100% similarity with the Delta sequence, versus 97.12% identity with the sequences of the Omicron subvariants BA.4 and BA.5 on sequence alignment using VectorBuilder version 2.1.817 (https://en.vectorbuilder.com/tool/sequence-alignment.html). Additionally, the sequence alignment and twenty genomic RNAs data tested for BA.5 using this assay are provided in Supplementary Figs. S1 , S2, and S3.

Our colorimetric RT-LAMP test exhibited a clinical specificity of 100%, a clinical sensitivity of 97.06%, and a clinical accuracy of 98.41% in comparison with conventional real-time RT-PCR. The assay’s PPV and NPV were 100.00% and 96.67%, respectively, indicating its high reliability in accurately distinguishing infected and non-infected individuals. The high specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV of the colorimetric RT-LAMP method for detecting the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 highlights its utility as a reliable diagnostic tool. The test represents a quick, reliable, cost-effective, and scalable alternative to nucleic acid amplification tests for monitoring variants of SARS-CoV-2 in large-scale population screening. Conducting periodic screening among high-risk groups within a community represents an efficient approach to tracking and controlling diseases. This method enables the identification of the Delta variant and the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in a single test. It is worth mentioning that our assay is the first colorimetric RT-LAMP that can differentiate the Delta variant from its generic SARS-CoV-2. The test could aid in studying COVID-19 demography and evolution, and facilitating proper effective control measure establishment to fight against the reemerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 in the future.

Methods

Primer design for RT-LAMP targeting the L452R SNP

The primer sets for RT-LAMP were manually designed to exclusively target the L452R mutation located in the RBD of the S gene within the SARS-CoV-2 genome (GenBank accession No. OP412303.1, Fig. 4a). The SNP U1355G changes nucleotide position 1355 from U to G, which changes the amino acid sequence in the spike protein from leucine to arginine (L452R). This SNP was matched with the complementary sequence of the FIP at its 3′ end. According to the methodology outlined by Mohon and Khumwan45,46, the FIP sequence was modified near the SNP site toward its 5′ end, resulting in the creation of nucleotide mismatches spanning up to three bases. LPF sequences were generated to recognize up to three base mismatches starting with the third nucleotide downstream from the 3′ end (Fig. 4b). The illustration in Fig. 4c displays the RT-LAMP primers for FIP (F1c + F2), BIP (B1c + B2), F3, B3, and LPF. The sequences of all primers are listed in Table 1. The primer sets were initially screened using the real-time RT-LAMP technique. The primer sets were evaluated by assessing their capacity to differentiate the Delta variant, which contains the L452R mutation, from the wild-type strain (Wuhan-Hu-1) of SARS-CoV-2. The Cq values obtained from the real-time RT-LAMP signals were utilized to construct specific criteria for identifying primer sets that demonstrated optimal differentiation between responses from the mutant and wild-type. The primer set utilized in this study was subsequently employed for colorimetric RT-LAMP assay.

Primer information for the RT-LAMP assay. (a) Schematic depiction of the RT-LAMP primer target location. The L452R mutation is a SNP located in the RBD of the spike gene within the SARS-CoV-2 genome. (b) Illustration demonstrating RT-LAMP primers designed to identify the L452R mutation in the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 using the sequence from GenBank: OP412303.1. The SNP of the L452R mutation is shown in the red box, changing nucleotide position 1355 from U to G (CTG to CGG), which generated 0–3 nucleotide base mismatches (pink highlighted) adjacent to the specific SNP position on F2 and LPF sequences. Primers F3, F2, B3, B2, F1c, B1c, and LPF and direction show primer sequence positions. (c) Schematic representation of the RT-LAMP primers used in this study. A FIP consisted of F1c and F2, and a BIP consisted of B1c and B2. The sequence of all primer sets is presented in Table 1.

Real-time RT-LAMP assay optimization

To determine the optimal temperature and primer sets for colorimetric RT-LAMP amplification, a 25-µL reaction mixture was prepared with the following components: 0.2 μM each of the outer primers F3 and B3, 1.6 μM each of the internal primers FIP and BIP, 0.4 μM loop primer LB, 1 × Isothermal Amplification Buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), 6 mM MgSO4 (New England BioLabs), 1.4 mM dNTPs (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.2 M betaine solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 × EvaGreen® Dye (Biotium Inc., Fremont, CA, USA), 8 U of Bst 2.0 WarmStart® DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), and 7.5 U of WarmStart® RTx Reverse Transcriptase (New England Biolabs). Five microliters of the RNA-positive Delta variant and wild-type strain (Wuhan-Hu-1) of SARS-CoV-2 were added to each real-time RT-LAMP reaction. The reaction was performed using the CFX96 Touch Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 60 °C or 63 °C for 75 min. Subsequently, heat inactivation was conducted at 85 °C for 2 min. Furthermore, the primer sets were assessed at each temperature. The outcomes of real-time RT-LAMP were examined using Cq values.

Colorimetric RT-LAMP assay

A colorimetric RT-LAMP assay was performed using 0.05 mM of xylenol orange disodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich) as a visual indicator. Each reaction consisted of the following components: 10 × low buffer, pH 8.5 [100 mM (NH4)2SO4), 500 mM KCl, 20 mM MgSO4, and 1% v/v Tween 20], 1.4 mM dNTPs, 0.2 M betaine solution, 6 mM MgSO4, 8 U of Bst 2.0 WarmStart® DNA polymerase, 7.5 U of WarmStart® RTx Reverse Transcriptase, 0.2 μM each of the outer primers (F3 and B3), 1.6 μM each of the inner primers (FIP and BIP), 0.4 μM loop primer (LB or LF), and 5 μL of the plasmid standard (positive template) and Wuhan-Hu-1 strain RNA of SARS-CoV-2 (wild-type, negative template). The reaction volume was adjusted to 25 μL with DNase/RNase-free water. The master mix setup and dye indicator preparations are provided in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

The positive template was generated using the plasmid standard containing the L452R mutation in the RBD region of SARS-CoV-2 (GenBank accession no. OP412303.1), which was purchased from GenScript Biotech (Piscataway, NJ, USA). The copy number of the plasmid standard was calculated using the following formula: number of copies/μL = [plasmid concentration (g/μL) × 6.022 × 1023 (molecules/mole)]/[(plasmid length × 660 (g/mole)) × 109 (ng/g)]. The reactions were performed with serial dilutions of the plasmid standard (50, 500, 5,000, 50,000, and 500,000 copies per reaction) at the appropriate temperature, and the color change from purple to yellow, which served as an indicator for the presence of the targeted L452R mutation in the template, was observed at 40, 60, and 75 min.

Analytical sensitivity

The plasmid standard was used to determine the analytical sensitivity of the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay. The LoD was assessed using sequential dilutions of the plasmid standard, including 0, 25, 50, 100, 500, and 1000 copies per reaction. Each dilution was examined in a series of 10 replicates. The hit rate was estimated to calculate the LoD95 using Probit regression analysis47 and Analyse-it software.

Analytical specificity

Verification of the analytical specificity of the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay was conducted using a plasmid standard and a group of genomic RNA samples. The initial SARS-CoV-2 strains included Wuhan-Hu-1 (wild-type) and the B.1.1.7 variant (Alpha). The respiratory infectious diseases caused by viral pathogens included human coronavirus (HCoV-229E), IAV subtype H3N2, IBV (Victoria lineage), and RSV. Furthermore, additional viruses, including PEDV, HAV, EV71, HSV, DENV1–4, ZIKV, CHIKV, and JEV. All genomic RNA samples were provided by the Virology Laboratory at the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University.

Clinical evaluation of the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay

In total, 126 nasopharyngeal and throat swab samples were obtained from the Tropical Medicine Diagnostic Reference Laboratory, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University to evaluate the performance of the colorimetric RT-LAMP assay for the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2. Then, all RT-LAMP reaction products were assessed by 2%-agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the specific amplification in positive and negative reactions. Gel images were taken using the Gel Doc XR + Gel Documentation System (Bio-Rad) with Novel Juice (supplied in 6 × loading buffer, GeneDireX, Taoyuan, Taiwan) as the intercalating dye. Nucleic acids were extracted from all nasopharyngeal and throat swab samples using the Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit employing the magnetic bead method (Zybio Inc., Chongqing, China). Subsequently, the extracted nucleic acids were analyzed for COVID-19 status through real-time RT-PCR using the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nucleic Acid Diagnostic Kit (Sansure Biotech, Hunan, China), which is considered as the gold standard method. Among the total samples tested, 68 specimens were identified as positive for COVID-19, whereas 58 samples were determined to be negative. Additionally, the positive samples were genotyped and sequenced to confirm the Delta variant and subsequently submitted to the GISAID database. We summarized the diagnostic test performance, including sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy, using MedCalc (https://www.medcalc.org/calc/diagnostic_test.php).

Data availability

The raw data cannot be shared publicly and is available from the corresponding author (pornsawan.lea@mahidol.ac.th) on reasonable request. The results and supplementary Information are made available in a public repository. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1f0KGQFveTBJ15beZ2iYjuwrUO3ozLfPu.

References

Eftekhari, A. et al. A comprehensive review of detection methods for SARS-CoV-2. Microorganisms 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020232 (2021).

Zhou, P. et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 (2020).

Zhu, N. et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 727–733. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 (2020).

Abdool Karim, S. S. & de Oliveira, T. New SARS-CoV-2 variants—clinical, public health, and vaccine implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1866–1868. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2100362 (2021).

Lauring, A. S. & Hodcroft, E. B. Genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2—what do they mean?. JAMA 325, 529–531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.27124 (2021).

World Health Organization. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern, https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern (2021).

Cherian, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations, L452R, T478K, E484Q and P681R, in the second wave of COVID-19 in Maharashtra India. Microorganisms 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9071542 (2021).

Kang, M. et al. Transmission dynamics and epidemiological characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant infections in Guangdong, China, May to June 2021. Euro Surveill. 27, 1. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.Es.2022.27.10.2100815 (2022).

Samieefar, N. et al. Delta variant: The new challenge of COVID-19 pandemic, an overview of epidemiological, clinical, and immune characteristics. Acta Biomed. 93, e2022179. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v93i1.12210 (2022).

Baral, P. et al. Mutation-induced changes in the receptor-binding interface of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant B.1.617.2 and implications for immune evasion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 574, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.08.036 (2021).

Chakraborty, C., Sharma, A. R., Bhattacharya, M., Agoramoorthy, G. & Lee, S. S. Evolution, mode of transmission, and mutational landscape of newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. mBio 12, e0114021. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01140-21 (2021).

Wrenn, J. O. et al. COVID-19 severity from Omicron and Delta SARS-CoV-2 variants. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 16, 832–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12982 (2022).

Bhattacharya, M., Chatterjee, S., Sharma, A. R., Lee, S. S. & Chakraborty, C. Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2: Current understanding of infection, transmission, immune escape, and mutational landscape. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 68, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12223-022-01001-3 (2023).

Gao, C. et al. SNP mutation-related genes in breast cancer for monitoring and prognosis of patients: A study based on the TCGA database. Cancer Med. 8, 2303–2312. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2065 (2019).

Gulay, K. et al. 40 minutes RT-qPCR Assay for Screening Spike N501Y and HV69–70del Mutations. bioRxiv, 2021.2001.2026.428302. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.26.428302 (2021).

Shipulin, G. A. et al. Development and application of an RT-PCR assay for the identification of the delta and omicron variants of SARS-COV-2. Heliyon 9, e16917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16917 (2023).

Hyman, L. B., Christopher, C. R. & Romero, P. A. Competitive SNP-LAMP probes for rapid and robust single-nucleotide polymorphism detection. Cell Rep. Methods 2, 100242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2022.100242 (2022).

Notomi, T. et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, E63. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.12.e63 (2000).

Aoki, M. N. et al. Colorimetric RT-LAMP SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic sensitivity relies on color interpretation and viral load. Sci. Rep. 11, 9026. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88506-y (2021).

Mori, Y., Kitao, M., Tomita, N. & Notomi, T. Real-time turbidimetry of LAMP reaction for quantifying template DNA. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 59, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbbm.2003.12.005 (2004).

Njiru, Z. K. et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) method for rapid detection of trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2, e147. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000147 (2008).

Dao Thi, V. L. et al. A colorimetric RT-LAMP assay and LAMP-sequencing for detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA in clinical samples. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eabc7075. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abc7075 (2020).

Amoia, S. S. et al. A colorimetric LAMP detection of Xylella fastidiosa in crude alkaline sap of olive trees in apulia as a field-based tool for disease containment. Agriculture 13, 1 (2023).

Dangtip, S. et al. Colorimetric detection of scale drop disease virus in Asian sea bass using loop-mediated isothermal amplification with xylenol orange. Aquaculture 510, 386–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.05.071 (2019).

Nawattanapaiboon, K. et al. Colorimetric reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) as a visual diagnostic platform for the detection of the emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Analyst 146, 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0AN01775B (2021).

Nuchnoi, P. et al. Applicability of a colorimetric reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) assay for SARS-CoV-2 detection in high exposure risk setting. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 285–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2023.01.010 (2023).

Jaroenram, W., Cecere, P. & Pompa, P. P. Xylenol orange-based loop-mediated DNA isothermal amplification for sensitive naked-eye detection of Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. Methods 156, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2018.11.020 (2019).

Varona, M. & Anderson, J. L. Advances in mutation detection using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. ACS Omega 6, 3463–3469. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c06093 (2021).

Hu, X. et al. Development and clinical application of a rapid and sensitive loop-mediated isothermal amplification test for SARS-CoV-2 infection. mSphere 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00808-20 (2020).

Lalli, M. A. et al. Rapid and extraction-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 from saliva by colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clin. Chem. 67, 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa267 (2021).

Lu, R. et al. A novel reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1 (2020).

Werbajh, S. et al. Colorimetric RT-LAMP detection of multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants and lineages of concern direct from nasopharyngeal swab samples without RNA isolation. Viruses 15, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15091910 (2023).

Lau, Y. L. et al. Real-time reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. PeerJ 8, e9278. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9278 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. RT-LAMP assay for rapid detection of the R203M mutation in SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 11, 978–987. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2022.2054368 (2022).

Iijima, T. et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and the L452R spike mutation using reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification plus bioluminescent assay in real-time (RT-LAMP-BART). PLOS ONE 17, e0265748. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265748 (2022).

El-Kafrawy, S. A. et al. Rapid and reliable detection of SARS-CoV-2 using direct RT-LAMP. Diagnostics (Basel) 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12040828 (2022).

Mautner, L. et al. Rapid point-of-care detection of SARS-CoV-2 using reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP). Virol. J. 17, 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-01435-6 (2020).

Mori, Y., Nagamine, K., Tomita, N. & Notomi, T. Detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction by turbidity derived from magnesium pyrophosphate formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289, 150–154. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2001.5921 (2001).

Supakitthanakorn, S. et al. Development of colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technique for rapid, sensitive and convenient detection of chrysanthemum chlorotic mottle viroid (CChMVd) in chrysanthemum. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 49, 1296–1306. https://doi.org/10.12982/CMJS.2022.079 (2022).

Alhamid, G. et al. Colorimetric and fluorometric reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) assay for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2. Funct. Integr. Genomics 22, 1391–1401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-022-00900-5 (2022).

Ventura, B. D. et al. Colorimetric test for fast detection of SARS-CoV-2 in nasal and throat swabs. ACS Sens 5, 3043–3048. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.0c01742 (2020).

Broughton, J. P. et al. CRISPR–Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 870–874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0513-4 (2020).

Patchsung, M. et al. Clinical validation of a Cas13-based assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 1140–1149. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-020-00603-x (2020).

Tegally, H. et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron lineages BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. Nat. Med. 28, 1785–1790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01911-2 (2022).

Khumwan, P. et al. Identification of S315T mutation in katG gene using probe-free exclusive mismatch primers for a rapid diagnosis of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis by real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Microchem. J. 175, 107108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2021.107108 (2022).

Mohon, A. N., Menard, D., Alam, M. S., Perera, K. & Pillai, D. R. A novel single-nucleotide polymorphism loop mediated isothermal amplification assay for detection of artemisinin-resistant plasmodium falciparum malaria. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofy011 (2018).

Stokdyk, J. P., Firnstahl, A. D., Spencer, S. K., Burch, T. R. & Borchardt, M. A. Determining the 95% limit of detection for waterborne pathogen analyses from primary concentration to qPCR. Water Res. 96, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.026 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sumonmal Uttayamakul, National Institute of Health, Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, who kindly provided genomic RNAs of Omicron subvariant BA.5 from clinical samples. All images in this study were created using PowerPoint software by the first author.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scholarship for the Development of High-Quality Research Graduates in Science and Technology project. This scholarship is a cooperation between the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) and Mahidol University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.T. planned, conducted, analyzed the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. S.P., W.J., and W.K. planned, provided the protocol for the RT-LAMP assay, analyzed the experiments, and revised the manuscript. N.K. and P.S. analyzed the experiments and revised the manuscript. P.L. planned, supervised, provided clinical samples, analyzed the experiments, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (MUTM: 2024-001-01) and the Mahidol University Biosafety Committee (MU 2023-051). All medical records were irreversibly anonymized. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the need for informed consent from all subjects was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thippornchai, N., Pengpanich, S., Jaroenram, W. et al. A colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification method targeting the L452R mutation to detect the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep 14, 21961 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72417-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72417-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multiple detection method for SARS-CoV-2 with aptamer cocktails depending on their localization in paper-based assays

BMC Infectious Diseases (2025)