Abstract

Cervical cancer begins in the cells lining the cervix and is caused by persistent infection with certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV). Initially, it has no symptoms, and later it causes pelvic pain, abnormal vaginal bleeding, and pain during intercourse. It is the fourth-ranked cancer among women, and many women die from cervical cancer every year, particularly in low-income countries and the majority could be prevented with early detection and treatment. In this study, we have taken Cervical Cancer DNA Replication and Repair-Related Protein with the PDBID- 3H15, 5VBN, and 6NT9 and performed the multitargeted molecular docking with the FDA-approved drug library using HTVS, SP and XP docking. Then, the poses were filtered with MM\GBSA for proper computations of free energy, identified a multitargeted inhibitor Droxidopa with docking and MM\GBSA scores ranging from − 5.559 to − 6.835 Kcal/mol and − 26.04 to − 37.33 Kcal/mol, respectively. We also performed interaction fingerprints revealing 2VAL, 2LYS, 1ALA, 1ARG, 1ASN, 1CYS, 1GLN, 1GLU, 1ILE, 1MET, 1PHE, 1PRO, 1SER, and 1THR were most interacted residues and computed the ADMET properties with QikProp and DFT with Jaguar, which supported the study and compounds’ suitability. Moreover, we performed the 100ns MD simulation in water, showing the controlled deviation and fluctuations of the residues with many interactions, and MM\GBSA was performed with the same trajectories, showing a better understanding of each frame’s total complex and binding-free energy. The whole study favours droxidopa as an inhibitor of cervical cancer DNA Replication and Repair-Related Proteins—however, experimental studies are needed before use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer stands as a formidable challenge to global public health, particularly impacting women in both developed and developing nations. Despite advancements in medical science and technology, it remains a leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality among women worldwide1,2. Cervical cancer embodies a complex disease paradigm that necessitates multifaceted approaches for effective prevention, early detection, and treatment, as it is rooted in the intricate interplay of biological, social, economic, and environmental factors3,4,5,6. Throughout history, cervical cancer has left an indelible mark on societies, shaping medical practices, public health policies, and socio-cultural narratives surrounding women’s health. From the pioneering work of George Papanicolaou in developing the Pap smear to the advent of HPV vaccines, the fight against cervical cancer has witnessed significant milestones that have revolutionised prevention and management approaches7,8. However, challenges persist, particularly in resource-limited settings where access to screening, vaccination, and treatment remains a pressing concern. By unpacking the molecular mechanisms driving cervical carcinogenesis and the evolving landscape of therapeutic interventions, we can provide clinicians, researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders with a nuanced understanding of the disease spectrum and avenues for collaborative action6,9,10,11,12. From HPV vaccination initiatives targeting adolescents to comprehensive screening programs for early detection of precancerous lesions, preventive interventions hold the key to reducing the burden of cervical cancer on global health systems and improving women’s health outcomes. Although multiple treatment options, including preventive vaccines, are available, it remains a formidable challenge that demands concerted efforts from the scientific community, healthcare providers, policymakers, and society13. By advancing our understanding of its complex aetiology, clinical manifestations, and preventive measures, we can pave the way for a future where cervical cancer ceases to be a threat to women’s health14,15,16.

In cervical cancer, the role of proteins such as Replication Initiation Factor MCM10, DNA Polymerase Epsilon, and the TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) is pivotal in understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms driving tumorigenesis17,18,19. MCM10, a key regulator of DNA replication, orchestrates the assembly and activation of the MCM complex, essential for DNA unwinding and initiation of replication forks, and dysregulation can lead to aberrant DNA replication, genomic instability, and tumorigenesis. Similarly, DNA Polymerase Epsilon, a critical enzyme involved in DNA synthesis and repair, ensures faithful replication of genomic DNA. However, perturbations in DNA polymerase epsilon activity or expression can result in replication stress, accumulation of DNA damage, and genomic instability, fostering the development of cervical cancer17,18,19. Furthermore, TBK1 is a crucial component of innate immune signalling, mediating the response to cytosolic DNA or RNA sensing, and dysregulated TBK1 signalling in cervical cancer can promote immune evasion, inflammation, and tumour progression, highlighting its significance in disease pathogenesis. These proteins also share pathways intersecting various cellular processes in cervical cancer development and progression. For instance, MCM10 and DNA Polymerase Epsilon are integral components of the DNA replication machinery, intersecting with cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, and apoptosis. Dysregulation of these pathways can disrupt genomic integrity, accumulating mutations and oncogenic transformations characteristic of cervical cancer17,18,19,20. Similarly, TBK1 contributes to innate immune surveillance against viral infections and cellular stress, intersecting with inflammation, immune evasion, and tumour immunity pathways. Dysregulated TBK1 signalling can foster an immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment, enabling tumour cells to evade immune surveillance and promote tumour growth17,18,19. In combating cervical cancer, multitargeted drug design emerges as a promising therapeutic strategy, aiming to target multiple proteins or pathways implicated in disease pathogenesis concurrently21,22,23. By leveraging structural insights from protein complexes, we can design small molecules or biologics that selectively disrupt specific protein-protein interactions or enzymatic activities critical for tumour growth and survival24,25. For example, multitargeted drugs may simultaneously inhibit MCM10 and DNA Polymerase Epsilon to disrupt DNA replication and induce synthetic lethality in cancer cells, enhancing the efficacy of conventional chemotherapy or radiation therapy26. Additionally, targeting TBK1 signalling could augment antitumor immune responses and sensitise cervical cancer cells to immunotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors, offering a synergistic approach to cancer treatment. Understanding the intricate roles of MCM10, DNA Polymerase Epsilon, TBK1, and cervical cancer pathogenesis and their shared pathways provides valuable insights for developing multitargeted therapeutic interventions. With structural data and innovative drug design approaches, we can potentially reduce the burden of cervical cancer and improve patient outcomes through more effective and targeted treatments27,28,29.

In this study, we selected three important cervical cancer proteins and performed multitargeted docking studies to identify a drug candidate that can target all three proteins together and slow the pathways, further slowing the cell growth in cervical cancer tissues. We identified the drug candidate with better docking and MM\GBSA scores, and then we performed molecular interaction fingerprints that showed a pattern for the drug’s interactions and performed the ADMET analysis, which favours the study. We extended our studies by DFT and MD simulation computations followed by the MM\GBSA computations on the trajectories file.

Methods

The methods of protein searching followed by multiple studies are shown in Fig. 1 to identify and validate the multitargeted drug candidate. The detailed methods are as follows-.

Protein preparation

Protein preparation is a crucial step in molecular modelling and drug discovery that involves optimising the structure of a protein molecule to ensure accuracy and reliability in subsequent computational analyses such as docking and molecular dynamics simulations4,21. This process typically includes removing water molecules, adding missing hydrogen atoms, assigning appropriate bond orders, and optimising side-chain conformations. Proper protein preparation enhances the quality and validity of computational results, aiding in designing effective therapeutic agents4,21. The 3D structure of the protein was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (https://rcsb.org/) with PDBID: 3H15 (replication initiation factor MCM10), 5VBN (human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit) and 6NT9 (human TBK1) with the resolution of 2.72 Å, 2.35 Å and 3.30 Å, respectively17,18,19,30,31,32. The downloaded structures were imported to the Schrodinger Maestro and prepared with the PPW (protein preparation workflow) tool33,34. The PDBID: 3H15 originally had DNA as chain B and protein as chain A with solvents and other metals/ions, and 5VBN originally had Chain A, B, E and F of protein with solvents and metals/ions, while the PDBID: 6NT9 has Chain A and B of protein with four native ligands17,18,19. In PPW, we capped the termini, filled in the missing side chains, assigned bond orders to the CCD database, replaced hydrogens, created disulphide bonds and zero-order bonds to metals and filled in the loops with Prime and generated hetero-state with Epik at pH 7.4 ± 233,35,36,37. In the optimisation tab, sample water orientation and crystal symmetry were used and optimised using PROPKA38. The minimisation was performed with OPLS4 forcefield and deleted water beyond 5Å of the protein39,40. After preparing the proteins, we only kept Chain A in all the cases and removed solvents and metals/ions to free the protein from miscalculation during docking17,18,19.

Ligand data collection and preparation

We have downloaded the FDA-approved drug library from https://www.selleckchem.com/ (3109 approved drugs) and prepared it with the LigPrep tool in Maestro41,42. Ligand preparation is essential in molecular modelling and drug discovery to ensure the accuracy and reliability of computational analyses such as docking and virtual screening. It involves optimising the structure of a ligand molecule by removing solvent molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, assigning appropriate bond orders, and optimising its conformation. Proper ligand preparation enhances the quality of molecular interactions and binding affinity predictions, facilitating the identification of potential drug candidates with desired pharmacological properties. We browsed the library with the file option, filtered the atoms beyond 500 atoms and used the OPLS4 forcefield40. In the ionisation, we have kept generating possible states at a target pH of 7 ± 2, used the classic Epik, generated the tautomers, and used Deslat. The stereoisomer computations were kept to retain specified chiralities and to generate 32 per ligand in the SDF file to import and use further33,37.

Grid generation and molecular docking

Glide Grid generation is essential before docking to create a 3D grid around the protein binding site, guiding ligand placement during docking simulations. This process accounts for the protein’s shape and electrostatic properties, ensuring accurate ligand binding predictions. Proper grid generation enhances docking precision, facilitating the identification of potential drug candidates. The Receptor Grid Generation tool was used to generate the grids on the complete structures of the protein for blind docking, as no native ligand was kept during the preparation33,43,44. The Van der Waals radius scaling was kept to a scaling factor of 1 and a partial charge cutoff of 0.25. The enclosing box was kept to and displayed to view whether it fitted adequately on the protein or not and at the centroid of selected residues, and then the size of dock ligands with length was adjusted in each case to make it fit on the proteins, and all the advanced options were kept default33,44. Protein-ligand docking is a computational technique used in drug design to predict small molecule ligands’ binding modes and affinities to protein targets. It simulates the interaction between a protein’s binding site and a ligand molecule, predicting their optimal spatial arrangement and binding strength. Docking provides insights into ligand-protein interactions, aiding in identifying and optimising potential drug candidates. We used the Virtual Screening Workflow tool for the Molecular Docking studies, browsed the prepared ligand file, combined input files, redistributed for sub-jobs, and generated unique properties to each compound to filter them. We used the QikProp-based descriptor generator, prefiltered the ligand with Lipinski’s rule, and skipped the preparation option in the VSW panel33,41,45,46. In the receptor panel, we browsed the prepared grid files, and in the docking panel, all the parameters were set for the High Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS), Standard Precision (SP) and Extra Precise (XP) docking followed by Molecular Mechanics-based Generalised Born Surface Area (MM\GBSA) computations33,43,44. The Epik state penalties were used for the docking with a scaling factor for the van der Waals radii of 0.80 and a partial charge cutoff of 0.1533,37. The 10% output of HTVS was passed to SP, and the top 10% of SP’s output was passed to XP, where we kept generating four poses per compound and passed 100% output files to MM\GBSA computations. The outputs were taken in the CSV files and analysed to identify which compound has interacted with all three protein with maximum (negative) docking scores.

Molecular interaction fingerprints

Molecular Interaction Fingerprint (IFP) is a computational method to represent and analyse molecular interactions between a ligand and a protein target. It generates a fingerprint or vector that captures the types and frequencies of specific interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic interactions, between the ligand and protein residues. IFP provides valuable insights into ligands’ binding mode and affinity, facilitating the design of novel drugs with improved efficacy and specificity22,23. The IFPs were computed using the Interaction Fingerprints tool in Maestro33. We selected all three proteins, identified ligands in complexes, and selected the receptor-ligand complex option with any contact to make the interaction plot. All sequences were then aligned while keeping PDBID: 3H15 as the reference sequence and generated the fingerprints. In the interaction matrix, we again went for any contact option and coloured the plot by residue sequence number for the N to C terminal of the proteins. We then kept only interacting residues to clarify the plot33.

Density functional theory (DFT)

DFT is a quantum mechanical method used to calculate the electronic structure of molecules, including drugs and drug candidates. In drug confirmation studies, DFT is crucial in predicting molecular properties such as geometry, energy, and reactivity36. By solving the Schrödinger equation for the electronic wave function, DFT provides insights into molecular stability, intermolecular interactions, and spectroscopic properties. This information aids in understanding the conformational preferences of drugs, predicting their bioactivity, and optimising their pharmacological properties for drug design and development. The DFT computations were performed with the Optimisation panel in Maestro, where we selected the B3LYP-D3 theory with a basis set of 6-41G** and included the workspace entry10,23,33. We kept the DFT option settings in the theory tab, and SCF spin treatment was automatic33,35. In the SCF tab, we kept the accuracy level for the Quick and atomic overlap for the initial guess. The convergence criteria were kept to 48 iterations with an energy change of 5e-05 Hartree with an RMS density matrix change of 5e-06. The convergence methods were kept to SCF level shift to 0.0 Hartree with no thermal smearing with the converge scheme of DIIS. In the optimisation, the maximum steps of 100 were kept, and the criteria were kept to default with the initial Hessian of Schlegel guess and coordinates of redundant internals33,35. Further, in the properties computations tab, vibrational frequencies were computed, followed by surfaces (molecular orbitals, density and potentials) were computed. We computed the Electrostatic potentials in the surfaces, average local ionisation energy (kcal/mol), noncovalent interactions and electron densities. The spin density was kept, and Molecular Orbitals for the Alpha and Beta for HOMO and LUMO were computed33,35.

Pharmacokinetics

ADMET stands for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity, representing drugs’ fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties47. Understanding ADMET properties is essential in drug discovery and development to assess potential drug candidates’ safety, efficacy, and pharmacological profile. ADMET studies evaluate how drugs are absorbed into the body, distributed within tissues, metabolised by enzymes, eliminated from the body, and whether they exhibit any toxic effects. Drug potency can be enhanced, adverse effects can be reduced, and therapeutic outcomes can be improved by optimising ADMET properties. The pharmacokinetics of the identified compound were computed with the QikProp tool, which includes multiple descriptors for the ADMET33,41. QikProp offers rapid predictions of multiple drug-like properties, facilitating efficient screening of compound libraries and customisable filters, and comprehensive analysis enables early-stage assessment and prioritising drugs33,41.

Molecular dynamics simulation and MM\GBSA studies

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational technique that simulates a system’s time-dependent behaviour of atoms and molecules. It provides insights into the dynamic behaviour and interactions of biomolecules such as protein and nucleic acids, aiding in understanding their structure, function, and dynamics at the atomic level. MD simulations can elucidate conformational changes, ligand binding events, and protein-ligand interactions, offering valuable information for drug discovery, protein engineering, and understanding biological processes. The Desmond package (https://www.deshawresearch.com/) in Schrodinger Maestro was used for the MD simulation33,48. The System Builder tool in Schrodinger Maestro was used where we selected the SPC water model in orthorhombic boundary conditions with box size calculation methods for the buffer in 10 × 10 × 10 Å and minimised the volume to check whether it fits on the protein-ligand complex or not33,49. We have added 3Cl− in PDBID: 3H15, 14Na+ in PDBID: 5VBN and 7Na+ in PDBID: 6NT9 and excluded the ion and salt placement within 20Å of ligand. We have not used any custom charges, and the OPLS4 forcefield was used to build the system file40. The prepared system builder file was loaded to the Schrodinger Maestro Molecular Dynamics panel for the production run with 100ns time and recording intervals of 100ps at 1.2 energy level to generate 100 frames. The NPT-ensemble class was used at 300 K temperatures and 1.01325 bar pressure, and the system was relaxed before simulation33,50. The Simulation Interaction Diagram tool was used to analyse the deviations, fluctuation and intermolecular interactions among the protein-ligand and other molecules of the solute and ions.

Molecular mechanics-based generalised born surface area (MM/GBSA) studies

The MM\GBSA studies were performed on the trajectories of the MD simulation files. The MM\GBSA for the computations of binding free energy and total complex energy with the following commands- export SCHRODINGER=/opt/schrodinger2022-4/ and $SCHRODINGER/run thermal_mmgbsa.py desmond_md_job_NAME-out.cms, and the output files in CSV were further filtered to better plot and understand it33,51.

Results

Preparation and reliability studies of protein structures

The protein preparation process for structure PDBID: 3H15 resulted in a meticulously refined model, ensuring structural integrity and accuracy. Comprehensive checks for common structural mistakes were conducted, with no errors detected, providing a solid foundation for further optimisation. Metal ions were effectively pre-treated to guarantee proper coordination and stability within the structure. Hydrogens were strategically removed and re-added to optimise hydrogen bonding patterns, enhancing the overall stability of the protein model33,35. The protein preparation documents the meticulous process of preparing the protein PDBID: 5VBN structure. Initially, common structural mistakes were checked for, but none were found. The next step involved pre-treating metals, which was completed. Following this, bond orders were assigned, and no changes were needed. Hydrogens were then removed and re-added, and metals were treated again. Di-sulphur bonds were created, and antibody regions were annotated, with a warning about sequence similarity scores being below a specific cutoff for reference sequences. Selenomethionines were converted, and missing loops were filled using Prime33,35. The structures were adjusted for pH 7.4 and a minimum probability of 0.01, with details provided for each input structure. The process concluded with Epik completing its task, filtering undesired states and idealising hydrogen temperature factors33,37. Protonation penalties were recalculated, and the combined total energy was reported. Various alternative states for specific residues and their respective energy gaps were identified. We optimised hydrogen positions, restrained minimisation, and subsequent refinement levels. The final energy reports were documented, providing insights into bond stretch, angle bending, torsion angle, Lennard Jones, and electrostatic energies. The results show a detailed process of preparing a protein structure with the identifier PDBID: 6NT9. The initial steps involve fixing common structure mistakes, treating metals within the structure, assigning bond orders, and adding or removing hydrogens as necessary. Subsequently, the process moves on to tasks such as creating disulphide bonds, annotating antibody regions, converting Selenomethionines, and filling missing loops using Prime33,35. For each missing loop, the system generates models to fill in the gaps. In this case, there were 10 missing loops, each with multiple models generated. After generating and combining these models, side chains are optimised, and a minimisation process is carried out. The minimisation process involves idealising hydrogen temperature factors and running restrained minimisation using the S-OPLS force field40. Following the refinement steps, the system reports the final energy of the system, potential energy, kinetic energy, temperature, and various energy contributions from the bond stretch, angle bending, torsion angle, 1,4 Lennard Jones, 1,4 electrostatic, Lennard Jones, and electrostatic interactions. The refinement process is iterated multiple times, reporting progress and energy details until reaching a desired refinement level. Various software tools and libraries, such as Schrodinger’s Impact and MMSHARE, perform atom typing, parameter assignments, energy and force calculations, and refinement operations. The results provide a comprehensive overview of the computational steps in preparing and refining the protein structure to achieve an energetically stable conformation suitable for further analysis and simulations. Table 1 comprehensively analyses the energy parameters for three distinct protein structures with PDBIDs: 3H15, 5VBN, and 6NT9. Each structure is assessed based on various energy components crucial for understanding its stability and behaviour. The total energy, comprising both potential and kinetic components, is reported in units of kilocalories per mole (kcal/mol). All structures’ structures, the total kinetic energy and temperature o, indicating a static state typical of molecular modelling simulations. The potential energy, which accounts for the interactions among atoms within the structure, mirrors the total energy values. Specific energy terms shed light on molecular interactions within the protein structures. Bond stretch energy, measured in kcal/mol, represents the energy associated with stretching chemical bonds, while angle bending energy (kcal/mol) reflects the energy required to bend these bonds. Torsion angle energy (kcal/mol) accounts for the energy in twisting the bonds around their axes. Non-bonded interactions are captured by 1,4 Lennard Jones energy (kcal/mol) and 1,4 electrostatic energies (kcal/mol), which describe interactions between atoms within a specified distance cutoff. Additionally, Lennard Jones energy (kcal/mol) and electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) encompass the total non-bonded interactions with short-ures, with short- and long-range contributions (Table 1). Notably, hydrogen bond energy is absent in all cases, indicating either a lack of hydrogen bonds or their exclusion from the energy calculations. This comprehensive energy analysis is treasured into the structural stability and interactions of proteins, providing a foundation for further investigations for drug design. Figure 2 is of 3D representation of prepared protein and the Ramachandran plot for its quality assessment.

Protein-ligand interaction analysis

Protein-ligand docking or interaction studies in drug design predict how small molecules bind to target protein using computational algorithms and scoring functions by evaluating binding poses and interactions. The interaction between the Droxidopa and Protein MCM10 (PDBID: 3H15) has produced a docking score of − 5.559 Kcal/mol and MM\GBSA score of − 26.04 Kcal/mol and formed two hydrogen bonds in contact with LYS351, LYS353 residues with different OH ligand atom and two salt bridges contact with GLU358, and ARG310 residues with N+H3 ligand’s atom, and O− atom (Fig. 3A,B). It has also generated the potential energy (S-OPLS) is calculated at − 222.474 kcal/mol, with bend energy (S-OPLS) of 424.47 kcal/mol, an LJ-14 energy (S-OPLS) of 852.365 kcal/mol, and dihedral energy (S-OPLS) of 405.957 kcal/mol (Table 2). This indicates a favourable interaction between Droxidopa and MCM10. The negative values for energy parameters suggest stable binding interactions. The high potential and dihedral energy indicate strong molecular interactions, likely contributing to the observed docking and MM/GBSA scores. The Human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit (PDBID: 5VBN) has shown a docking score of − 6.835 Kcal/mol and MM/GBSA score of − 37.33 Kcal/mol and formed six hydrogen bonds interactions among ASN491 and N+H3, PHE242, THR245, and SER447 residues with three OH atoms, ASN491 residue with O atom, and formed a salt bridge contact among LYS443 residue and O− atom of the Droxidopa ligand (Fig. 3C,D). The potential energy (S-OPLS) is much higher at − 2637.703 kcal/mol, reflecting a more energetically favourable interaction. The bending energy (S-OPLS) is 2631.907 kcal/mol, LJ-14 energy (S-OPLS) is 5651.879 kcal/mol, and dihedral energy (S-OPLS) is 2915.993 kcal/mol. The docking score is − 6.835 kcal/mol, with an MM/GBSA score of − 37.33 kcal/mol, indicating a strong binding affinity between Droxidopa and the B-subunit of Human DNA polymerase epsilon. The high potential energy and LJ-14 energy suggest significant van der Waals interactions, contributing to the stability of the complex (Table 2). The interaction of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (PDBID: 6NT9) showed a docking score of − 6.436 Kcal/mol and an MM\GBSA score of − 20.05 Kcal/mol and has formed seven hydrogen bonds interaction among VAL265 and CYS267 residues with the N+H3 atom, CYS267, LEU269, and ARG427 residues with two OH atoms and TYR427 and ARG427 residues with the O atom of the Droxidopa ligand (Fig. 3E,F). The complex has generated potential energy (S-OPLS) is also high at − 4824.668 kcal/mol, with bend energy (S-OPLS) of 2791.588 kcal/mol, LJ-14 energy (S-OPLS) of 6229.301 kcal/mol, and dihedral energy (S-OPLS) of 2330.94 kcal/mol, indicating a favourable interaction (Table 2)40. The high LJ-14 energy suggests strong van der Waals interactions, contributing to the stability of the complex. The energy parameters provide valuable insights into the stability and strength of the molecular interactions observed in the docking studies. The negative values indicate favourable interactions, with higher negative values suggesting stronger binding affinities. Understanding these energy parameters can help predict the effectiveness of potential drug candidates and optimise their molecular structures for enhanced binding interactions.

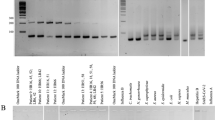

Molecular interaction fingerprints

IFPs aid in drug design by capturing and quantifying the unique patterns of molecular interactions between drugs and target proteins. These fingerprints provide insights into binding modes, key interactions, and structural motifs, guiding the design of novel compounds with optimised pharmacological properties and enhanced therapeutic efficacy. The residues that interact with the ligand Droxidopa are crucial in determining its binding affinity and specificity, and those residues are 2VAL, 2LYS, 1ALA, 1ARG, 1ASN, 1CYS, 1GLN, 1GLU, 1ILE, 1MET, 1PHE, 1PRO, 1SER, 1THR (Fig. 4). Ala (Alanine) residues provide hydrophobic interactions, contributing to the drug’s stability within the binding site. Arg (Arginine) residues can form hydrogen bonds with the ligand, enhancing binding affinity through electrostatic interactions. ASN (Asparagine) residues can participate in hydrogen bonding, aiding in specific interactions with the ligand. CYS (Cysteine) residues might form covalent bonds with the ligand, potentially leading to irreversible binding and modulation of drug activity. Gln (Glutamine) residues can engage in hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, contributing to the stability of the drug-receptor complex. Glu (Glutamic Acid) residues may participate in ionic interactions with the ligand, influencing binding affinity and specificity. Ile (Isoleucine) residues contribute to hydrophobic interactions, stabilising the drug within the binding pocket. Lys (Lysine) residues can form hydrogen bonds and salt bridges, facilitating electrostatic solid interactions with the ligand. Met (Methionine) residues provide hydrophobic interactions and can participate in hydrogen bonding with the ligand. Phe (Phenylalanine) residues contribute to hydrophobic interactions, enhancing the stability of the drug-binding site complex. Pro (Proline) residues may induce conformational changes in the binding site, affecting the orientation and stability of the ligand. Ser (Serine) residues can form hydrogen bonds with the ligand, contributing to specific interactions within the binding pocket. THR (Threonine) residues provide hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, influencing the binding mode and affinity of the drug. VAL (Valine) residues contribute to hydrophobic interactions, stabilising the drug within the binding pocket (Fig. 4). The diverse interactions between Droxidopa and these residues contribute to its binding affinity, specificity, and pharmacological effects. Understanding these interactions is crucial for optimising the design of drugs targeting the same or similar binding sites, potentially leading to improved therapeutics.

DFT and pharmacokinetics

DFT computations aid drug design by predicting molecular properties crucial for ligand stability, and analysing HOMO and LUMO levels provides insights into electronic structure and reactivity, guiding the selection of stable ligands. Electron density maps reveal charge distribution, while electrostatic potential maps highlight regions prone to interactions, aiding in ligand optimisation. This comprehensive approach ensures the selection of stable ligands for effective drug design. The DFT computations performed using the Jaguar program reveal significant insights into the properties of Droxidopa as a potential multitargeted inhibitor for cervical cancer proteins. The spin multiplicity of 1 indicates a stable electronic configuration. Employing the UDFT(b3lyp-d3)/SOLV method with a 6–31 g** basis set, the gas phase energy is calculated as − 780.492658 kcal/mol, while the solution phase energy is slightly lower at − 780.52904 kcal/mol. The solvation energy, − 22.83 kcal/mol, highlights the impact of the surrounding environment on the molecule’s stability (Fig. 5A). Relative energy refers to the difference in energy between different conformations or states within a system, providing insights into stability and reactivity. Grad Max and Grad RMS represent the energy gradient’s maximum and root mean square values, respectively, indicating the molecular structure’s magnitude and overall stability, as shown by the proper graphs in Fig. 5A. Disp Max and Disp RMS denote the maximum and root mean square values of the displacement of atoms, offering information on molecular flexibility and conformational changes. Unsigned dE represents the unsigned difference in energy between consecutive optimisation steps, highlighting the convergence of computational methods and the accuracy of results. These parameters collectively impact the reliability and accuracy of computational simulations, guiding the interpretation of molecular properties and behaviour in various environments or biological contexts. Analysis of molecular orbitals shows the alpha HOMO and LUMO at − 0.213568 and − 0.011152, respectively, indicating favourable electronic properties for reactivity (Fig. 5A,B). Similarly, the beta HOMO and LUMO exhibit similar energy levels. Electrostatic potential maps reveal a minimum of − 52.62 kcal/mol and a maximum of 67.88 kcal/mol, indicating regions of attraction and repulsion, respectively. The overall mean electrostatic potential is 3.02 kcal/mol, with a balanced distribution between positive and negative regions. The ALIE analysis further elucidates the molecule’s interaction with its surroundings, with a mean energy of 275.62 kcal/mol. These comprehensive computational results provide valuable insights into Droxidopa’s suitability as a multitargeted inhibitor for cervical cancer proteins, aiding in its further optimisation and development as a potential therapeutic agent (Fig. 5A,B).

(A). The DFT computations using the Jaguar Program showed various energy, including the relative energy, which converged around 28 steps. (B) Showing DFT computations using the Jaguar Program showing the HOMO-LUMO (α & β) sites, electron density map and electrostatic potential throughout the Droxidopa structure.

Droxidopa, a pharmaceutical compound, exhibits various pharmacokinetic properties determined through computational analysis using tools such as QikProp33,41. The descriptors reveal various characteristics crucial for understanding its behaviour within biological systems. Firstly, considering its molecular structure, Droxidopa comprises 15 atoms, including 6 ring atoms, and forms 15 bonds with 7 rotors. Such structural information provides insights into its overall size and complexity, which can impact its pharmacokinetics. The compound demonstrates solubility with a logarithm of the partition coefficient between octanol and water (QPlogPo/w) of − 2.773, indicating its potential for distribution between lipid and aqueous phases. Additionally, its polar surface area (PSA) of 129.458 square angstroms further characterises its interaction potential with biological membranes and transport proteins. Droxidopa exhibits moderate lipophilicity, as indicated by its logarithm of the octanol-water partition coefficient (QPlogPw) of 14.137, suggesting a tendency for distribution into lipid-rich environments. This is complemented by its QPlogBB value of − 1.63, indicating a slight ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, essential for drugs targeting the central nervous system (Table 3). Furthermore, the compound displays favourable characteristics related to gastrointestinal absorption, with a human oral absorption percentage of 3.026%. This parameter is crucial for understanding orally administered drugs’ bioavailability and potential therapeutic efficacy. In terms of its electronic properties, Droxidopa exhibits molecular polarizability (QPpolrz) of 16.613 cubic angstroms, reflecting its ability to induce temporary dipoles in response to an external electric field. Such polarizability contributes to the compound’s intermolecular interactions and solvation behaviour. Moreover, the compound displays a dipole moment of 2.491 Debye, indicating a degree of charge separation within the molecule, which can influence its interaction with biological targets and transport proteins. In addition to physicochemical properties, Droxidopa also demonstrates characteristics related to molecular geometry and connectivity. For instance, it exhibits an average eccentricity of 6.333 and an average vertex distance degree of 49.333, highlighting the distribution of atoms within the molecule and their spatial relationships (Table 3). The compound’s topological parameters, such as the Balaban distance connectivity index and the connectivity chi-1, provide further insights into its molecular structure and connectivity patterns, which are relevant for understanding its biological activity and pharmacological effects. The comprehensive analysis of Droxidopa’s pharmacokinetic properties reveals its potential as a pharmaceutical agent, with characteristics conducive to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion within biological systems. These insights are valuable for guiding further experimental studies and optimising the compound’s therapeutic utility in clinical applications.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Desmond package in Schrodinger Maestro was used to conduct a 100 nanosecond MD simulation of Droxidopa in a complex with all three protein33,48. Analysis revealed dynamic interactions between Droxidopa and proteins, highlighting potential binding modes and stability over time. This simulation helps understand the behaviour of Droxidopa in complex biological environments. The droxidopa in complex with PDBID: 3H15 has generated 28,910 atoms, the droxidopa in complex with PDBID: 5VBN has generated 73,117 atoms, and the droxidopa in complex with PDBID: 6NT9 has generated 110,088 atoms which were loaded and kept for the production run. The detailed results are as follows-.

Root mean square deviation

The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) measures the average distance between the atoms of two superimposed molecules. In the context of molecular dynamics simulations, RMSD quantifies the deviation of atomic positions from a reference structure over time. It is a crucial metric for assessing the stability and convergence of protein-ligand complexes during simulations. Droxidopa in complex with MCM10 protein (PDBID: 3H15) initially deviated to 1.69 Å in the case of protein, while the ligand deviated to 2.30 Å at 0.10 ns. After that, the complex showed a stable performance during the complete simulation period and at 100 ns, protein deviation was 4.01 Å while ligand deviation was noted to be 22.33 Å, and after neglecting the initial deviations, RMSD of protein showed acceptable deviations (Fig. 6A). The human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit (PDBID: 5VBN) complex with Droxidopa at the beginning deviated to 1.44 Å for protein, while the ligand to 0.66 Å at 0.10 ns and it keeps deviating and, at 100 ns, the protein deviation was 2.73 Å, and the ligand deviation was 5.44 Å, showing stability after ignoring the initial deviation (Fig. 6B). The TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (PDBID: 6NT9) in complex with droxidopa initially deviated to 1.60 Å and the ligand to 1.32 Å, at 0.10 ns, and it keeps showing the deviation, and at 100 ns, the protein deviated to 4.19 Å while the ligand deviated to 2.38 Å, and after ignoring the first 1ns complex, it displayed acceptable performance (Fig. 6C). In the case of Droxidopa complexes with MCM10 (PDBID: 3H15), human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit (PDBID: 5VBN), and TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (PDBID: 6NT9), initial deviations were observed. However, after disregarding these, all complexes displayed acceptable stability, with fluctuations in RMSD over time indicating dynamic interactions between the ligand and proteins. Overall, RMSD analysis offers insights into the behaviour and convergence of protein-ligand complexes during simulations.

Root mean square fluctuations

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) calculates the average deviation of atomic positions from their average positions throughout a molecular dynamics simulation. It provides insight into the flexibility and dynamics of individual residues within a protein or protein-ligand complex, aiding in identifying regions undergoing significant conformational changes. The complex of MCM10 protein (PDBID: 3H15) with Droxidopa has shown some fluctuating residues beyond 2Å are- GLN235, TYR236, SER252-GLU255, ARG258, LYS259, PRO297-LYS304, LYS353-GLU358, ALA383-GLN393, ASP399, and TYR405-VAL407 and the most interacting residues were ACE234-LYS240, ARG245, LYS248, SER254-ARG258, ARG267, GLN270, LYS293, SER299, ASN301, ASN302, LYS304, PHE306, ARG310, LEU314-LYS319, SER322, PHE324, PHE326, ASP328, LYS331, GLN338, ASN348, MET350-GLU358, SER362, ASP364, VAL376, ASP377, LEU378, THR380-GLN393, and LEU397-VAL407 (Fig. 6D). The complex of Human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit (PDBID: 5VBN) with Droxidopa has shown some fluctuating residues beyond 2Å are- HIS84, ASN113, GLU145, PHE147-SER161, THR175-LYS177, GLU192, GLY193, GLU281, SER432-ASN434, GLY526, PHE527, SER2150-PHE2163, LYS2171, SER2174-VAL2181, CYS2187-ALA2192, LYS2223, CYS2224, SER2237-ALA2239, PRO2282 and many of them has interacted with droxidopa are PHE147, HIS214, SER215, TYR218, PHE240, PHE242, PRO243, PRO244, THR245, ASN434, ASN439, LYS443, THR444, SER447, THR490, ASN491, and THR492 (Fig. 6E). The TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (PDBID: 6NT9) in complex with Droxidopa has shown many fluctuating residues beyond 2Å are- MET1-ASN6, SER12, LYS29-ASP33, ILE43-ARG54, GLU75-HIS81, GLY146-GLN150, GLU165, ASP166, ASP167, SER172, LEU173, MET184-LYS197, PHE224-ARG228, LYS251-GLY255, ASP288, -LYS291, SER328-HIS369, HIS403-ASP409, CYS471-GLN581, and PHE638-LEU658, and the interacting residues are TYR105, GLU109, ASP262-GLY272, GLN274, ALA321, HIS322, LYS323, GLN342, GLY391, LEU392, ILE393, TYR424, ARG427, ILE428, THR431, TYR435 (Fig. 6F). The fluctuations in residues during molecular dynamics simulations can be attributed to several factors, including conformational changes, solvent exposure, and interactions with the ligand or neighbouring residues. Conformational changes in the protein structure, such as loop movements or side-chain rotations, can lead to fluctuations in residue positions. Solvent exposure may also influence residue fluctuations, as residues on the protein surface are more susceptible to solvent interactions and fluctuations. Interactions with the ligand or neighbouring residues can significantly impact residue fluctuations. Residues directly involved in binding interactions with the ligand may experience fluctuations as they adjust their conformations to optimise binding. Additionally, neighbouring residues that indirectly interact with the ligand or undergo allosteric changes due to ligand binding can also exhibit fluctuations. In the case of the MCM10 protein complex with Droxidopa (PDBID: 3H15), fluctuating residues beyond 2Å include regions involved in ligand binding, suggesting dynamic interactions between the protein and ligand. Similarly, in the complexes of human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit (PDBID: 5VBN) and TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (PDBID: 6NT9) with Droxidopa, fluctuating residues are observed, indicating dynamic behaviour of these complexes during simulations. The most fluctuating residues are often located in flexible protein regions, such as loops or termini, where structural changes are more likely to occur. Additionally, residues involved in ligand binding sites or regions undergoing conformational changes due to ligand binding tend to exhibit higher fluctuations.

Showing the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of droxidopa in complex with (A) PDBID: 3H16, (B) PDBID: 5VBN, (C) and PDBID: 6NT9 where red shows the ligand deviations, blue shows the Cα deviations and side chains are also shown. Also, the root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of droxidopa in complex with (D) PDBID: 3H16, (E) PDBID: 5VBN, (F) and PDBID: 6NT9, where blue shows the fluctuation in Cα, and green lines shows the residues interacting the ligand.

Simulation interaction diagrams

A Simulation Interaction Diagram (SID) visually represents the interactions between a ligand and a protein during molecular dynamics simulations. Various interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic interactions, are illustrated throughout the simulation. SIDs are valuable for understanding the dynamic behaviour of protein-ligand complexes and identifying key interaction patterns that contribute to binding affinity and stability. The MCM10 protein (PDBID: 3H15) in complex with Droxidopa interacts with many hydrogen bonds among LYS315, ASP316, CYS391, GLN404 residues, and CYS381, ASP318 residues with water molecules along N+H3 atom, THR392, TYR402 residues, and LEU314 residue with water molecule along OH atom and ARG384, CYS391, residues and LYS385 residue with water molecules along two O atom. Also, it forms a salt bridge that contacts ASP316 residue with the N+H3 atom of the ligand (Fig. 7A,B). The Human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit (PDBID: 5VBN) in complex with Droxidopa interacts with hydrogen bonds along THR245, PHE242 residues, and SER215, ASN491, THR492 residues with water molecules along three OH atoms and LYS443, ASN491, SER215 residues with two O atoms. Additionally, two pi-cation contacts HIS214 residue with N+H3 atom and LYS443 residue with the benzene ring and form a salt bridge contact LYS443 residue with O atom of the ligand (Fig. 7C,D). Interaction between the TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (PDBID: 6NT9) and Droxidopa involves fifteen water molecules that act as water bridges. The hydrogen bonds among CYS267, VAL265, LEU269 residue with N+H3 atom, ILE369, ARG271, PRO264, GLN274, GLY391 residues with water molecules interact with three OH atoms and TYR424, ARG427 residues, and SER268, ILE393 residues with water molecules along two O atoms of the Droxidopa ligand (Fig. 7E,F). Analysis of Droxidopa complexes with MCM10, DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit, and TANK-binding kinase 1 reveals diverse interaction patterns, including the H-bonds, water bridges, pi-cation, and salt bridges contribute to complex stability, highlighting the intricate molecular interactions essential for ligand binding.

Showing the simulation interaction diagram (SID) of droxidopa in complex with (A) PDBID: 3H16, (C) PDBID: 5VBN, (E) and PDBID: 6NT9 and the bar graph shows the count of different interaction types of (B) PDBID: 3H16, (D) PDBID: 5VBN, (F) and PDBID: 6NT9, where blue shows water bridges, red shows the ionic interactions, grey shows the hydrophobic and the green shows the H-bonds.

MM\GBSA studies

The Molecular Mechanics Generalised Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) method is a powerful tool to estimate biomolecular complexes’ binding free energy, such as protein-ligand interactions. By analysing the results obtained from MM/GBSA calculations performed using Schrodinger Maestro, where 100 nanosecond molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted for each protein-ligand complex, we can gain insights into the performance of the method as the number of frames increases. As the number of frames increases from 0 to 1000, the MM/GBSA method provides a comprehensive understanding of the energetics of protein-ligand binding (Fig. 8). At frame 0, the complex energies for all three complexes, 3H15, 5VBN, and 6NT9, are relatively high, indicating unfavourable interactions between the protein and ligand. This is reflected in the negative binding free energy values, suggesting weak or non-existent binding between the molecules. As the simulation progresses, the complex energies fluctuate, reflecting the dynamic nature of the protein-ligand complexes within the simulated environment. Notably, for complex 3H15, there is a gradual decrease in complex energy over the first few frames, indicating a stabilisation of the protein-ligand complex (Fig. 8). This is accompanied by a corresponding increase in the binding free energy, suggesting a strengthening of the protein-ligand interaction. However, for complexes 5VBN and 6NT9, the complex energies remain relatively high throughout the simulation, indicating persistent unfavourable interactions between the protein and ligand. Despite fluctuations in energy values, there is no clear trend towards stabilising or strengthening the protein-ligand complex. Overall, the performance of the MM/GBSA method varies depending on the specific protein-ligand complex analysed. While it demonstrates the ability to capture dynamic changes in the energetics of protein-ligand interactions, its effectiveness in predicting binding affinities may be limited by the complexity of the molecular system and the accuracy of the force field parameters used in the simulations. In conclusion, the MM/GBSA method provides valuable insights into the energetics of protein-ligand binding, but its performance can vary depending on the specific molecular system studied. Further refinement and validation of the method may be necessary to improve its predictive accuracy for drug discovery and design applications.

Discussion

The comprehensive analysis presented in this study delves into various aspects of protein structure preparation, protein-ligand interactions, molecular interaction fingerprints, DFT computations, pharmacokinetics, MD simulations, and MM/GBSA studies. Each of these components contributes treasured insights into understanding the molecular interactions between the drug Droxidopa and its target protein (MCM10, Human DNA polymerase epsilon B-subunit, and TANK-binding kinase 1), aiding in the rational design and optimisation of therapeutic agents. The protein preparation process for structure PDBID: 3H15 yielded a meticulously refined model, free of errors, ensuring structural integrity and accuracy. Metal ions were pre-treated for proper coordination and stability, while strategic hydrogen optimisation enhanced bonding patterns and stability. Antibody regions were annotated, missing loops filled, and termini capped, ensuring completeness and accuracy. Extensive refinement included hydrogen bond network optimisation and pKa recalibration for physiological relevance. Restrained minimisation with S-OPLS force field further refined the structure, yielding an optimised protein model for drug design projects. Similarly, for PDBID: 5VBN, the process involved thorough checks, metal pre-treatment, hydrogen optimisation, and loop filling. For PDBID: 6NT9, the steps included fixing structure mistakes, treating metals, hydrogen adjustments, disulphide bond creation, and loop filling. Iterative refinement, including restrained minimisation, ensured energetically stable conformations. Software tools like Schrodinger’s Impact and MMSHARE facilitated atom typing, parameter assignments, and energy calculations throughout the process. The protein-ligand interaction analysis elucidates the molecular mechanisms underlying the binding of Droxidopa to its target proteins. By employing computational algorithms and scoring functions, the study predicts binding poses and interactions, providing valuable insights into the binding affinity and specificity of the drug-protein complexes. The docking and MM/GBSA scores indicate strong interaction affinities among Droxidopa and the target proteins, supported by salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals interactions. Moreover, the analysis of energy parameters, such as potential energy, bending energy, and LJ-14 energy, highlights the stabilising forces driving the formation of the protein-ligand complexes. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the molecular basis of protein-ligand interactions in rational drug design, guiding the selection and optimisation of potential drug candidates for therapeutic intervention. The molecular interaction fingerprints provide a detailed characterisation of the key residues involved in the binding of Droxidopa to its target proteins. By capturing the unique patterns of molecular interactions, the fingerprints offer valuable insights into the binding modes, key interactions, and structural motifs essential for ligand recognition and binding. The diverse interactions observed, including salt bridges, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and pi-cation contacts, underscore the complex nature of protein-ligand interactions. Understanding these interactions is crucial for optimising the design of novel compounds with enhanced pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy. The comprehensive analysis of molecular interaction fingerprints provides a roadmap for the rational design of drugs targeting the same or similar binding sites, offering potential avenues for developing improved therapeutics.

The DFT computations and pharmacokinetic analysis shed light on the molecular properties and pharmacological characteristics of Droxidopa. The study offers insights into the drug’s pharmacokinetic profile by predicting molecular properties crucial for ligand stability and analysing electronic structure and reactivity. The analysis of HOMO and LUMO levels provides valuable information about electronic properties relevant to ligand reactivity and interaction with biological targets. Moreover, examining physicochemical properties, such as solubility, lipophilicity, and gastrointestinal absorption, offers insights into the drug’s bioavailability and distribution within biological systems. The comprehensive characterisation of Droxidopa’s pharmacokinetic properties provides a foundation for understanding its behaviour in vivo and guiding further experimental studies to optimise its therapeutic utility.

The MD simulations provide dynamic insights into the stability and behaviour of Droxidopa-protein complexes in 100ns. By analysing RMSD, RMSF, and simulation interaction diagrams, the study elucidates the dynamic interactions between the ligand and protein during simulation. The fluctuations observed in RMSD and RMSF highlight the dynamic nature of protein-ligand complexes, with residues undergoing conformational changes and fluctuations in response to ligand binding. The simulation interaction diagrams reveal diverse interaction patterns, including hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and water bridges, contributing to the stability and specificity of the protein-ligand complexes. It offers valuable insights into the dynamic behaviour of Droxidopa-protein complexes, providing a deeper understanding of their structural dynamics and stability. The MM/GBSA studies provide a quantitative assessment of the binding free energy of protein-ligand complexes, offering insights into the energetics of protein-ligand interactions. The study evaluates the stability and strength of protein-ligand binding by analysing complex energies and binding free energy values throughout the simulation. The fluctuations observed in complex energies reflect the dynamic nature of protein-ligand complexes, with variations in binding free energy indicating changes in the stability of the complexes over time. The MM/GBSA method offers a powerful tool for estimating binding affinities and guiding the selection of potential drug candidates for further development. However, the method’s effectiveness may be influenced by the complexity of the molecular system and the accuracy of force field parameters.

Conclusion

The comprehensive computational analyses conducted in this study provide valuable insights into the structural, energetic, and dynamic aspects of PL interactions involving Droxidopa with cervical cancer DNA Replication and Repair-Related Proteins, which were identified after extensive computations. Through protein structure preparation, molecular docking studies, molecular interaction fingerprints, DFT computations, pharmacokinetic evaluations, molecular dynamics simulations, and MM/GBSA studies, we gained a deeper understanding of these complexes’ binding mechanisms, energetics, and stability. The docking and MM\GBSA scores ranged from − 5.559 to − 6.835 Kcal/mol and − 26.04 to − 37.33 Kcal/mol, respectively, and interaction fingerprints revealed the most interacted residues were 2VAL, 2LYS, 1ALA, 1ARG, 1ASN, 1CYS, 1GLN, 1GLU, 1ILE, 1MET, 1PHE, 1PRO, 1SER, and 1THR. The findings highlight the diverse interactions and dynamic behaviour exhibited by the protein-ligand complexes, underscoring the complexity of drug-protein interactions in rational drug design. These insights contribute to designing and optimising Droxidopa with improved pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy. Further experimental validation and refinement of computational models will be crucial for translating these findings into practical applications in drug discovery and development.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Yusuf, M. Perspectives on cervical cancer: Insights into screening methodology and challenges. Cancer Screen. Prev.3 (1), 52–60 (2024).

Vallikad, E. Cervical cancer: The Indian perspective. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet.95, S215–S233 (2006).

Ahmad, S. & Raza, K. An extensive review on lung cancer therapeutics using machine learning techniques: State-of-the-art and perspectives. J. Drug Target.32, 635 (2024).

Ahmad, S. et al. In-silico analysis reveals Quinic acid as a multitargeted inhibitor against cervical cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.41, 1–17 (2022).

Alghamdi, Y. S. et al. Unveiling the multitargeted potential of N-(4-aminobutanoyl)-S-(4-methoxybenzyl)-L-cysteinylglycine (NSL-CG) against SARS CoV-2: A virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.41(14), 6633–6642 (2023).

Reynolds, L. A. & Tansey, E. History of cervical cancer and the role of the Human Papillomavirus, 1960–2000 (Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2009).

Okunade, K. S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.40(5), 602–608 (2020).

Mammas, I. & DA, S. George N. Papanicolaou (1883–1962): Fifty years after the death of a great doctor. Sci. Humanit. J. BUON17(1), 180–184 (2012).

Ahmad, S. et al. Illustrious implications of nature-inspired computing methods in therapeutics and computer-aided drug design. In Nature-Inspired Intelligent Computing Techniques in Bioinformatics 293–308 (Springer, 2022).

Ahmad, S. et al. Multisampling-based docking reveals Imidazolidinyl urea as a multitargeted inhibitor for lung cancer: An optimisation followed multi-simulation and in-vitro study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.42 1–18 (2023).

Alghamdi, S. et al. Unveiling the multitargeted potency of Sodium Danshensu against cervical cancer: A multitargeted docking-based, structural fingerprinting and molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1–13 (2023).

Ali, C., Makata, N. & Ezenduka, P. Cervical cancer: A health limiting condition. Gynecol. Obstet. (Sunnyvale)6(378), 2161–0932 (2016).

Bonfiglio, T. A. Gynecologic cytopathology: Historical perspective, current status, and future outlook. AJSP Rev. Rep.10(3), 98–105 (2005).

Alturki, N. A. et al. In-silico screening and molecular dynamics simulation of drug bank experimental compounds against SARS-CoV-2. Molecules27(14), 4391 (2022).

Alzamami, A. et al. Hemi-Babim and fenoterol as potential inhibitors of MPro and papain-like protease against SARS-CoV-2: An in-silico study. Medicina58(4), 515 (2022).

Mehmood, A. et al. Structural dynamics behind clinical mutants of PncA-Asp12Ala, Pro54Leu, and His57Pro of Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with pyrazinamide resistance. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.7, 404 (2019).

Warren, E. M. et al. Physical interactions between Mcm10, DNA, and DNA polymerase α. J. Biol. Chem.284(36), 24662–24672 (2009).

Baranovskiy, A. G. et al. Crystal structure of the human Polϵ B-subunit in complex with the C-terminal domain of the catalytic subunit. J. Biol. Chem.292(38), 15717–15730 (2017).

Zhang, C. et al. Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature567(7748), 394–398 (2019).

Akash, S. et al. Novel computational and drug design strategies for inhibition of human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer and DNA polymerase theta receptor by apigenin derivatives. Sci. Rep.13(1), 16565 (2023).

Ahmad, S. et al. Multitargeted molecular dynamic understanding of butoxypheser against SARS-CoV-2: An in silico study. Nat. Prod. Commun.17(7), 1934578X221115499 (2022).

Ahmad, S. et al. Reporting dinaciclib and theodrenaline as a multitargeted inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2: An in-silico study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.41(9), 4013–4023 (2023).

Ahmad, S. & Raza, K. Identification of 5-nitroindazole as a multitargeted inhibitor for CDK and transferase kinase in lung cancer: A multisampling algorithm-based structural study. Mol. Divers.28, 1–14 (2023).

Akash, S. et al. Anti-parasitic drug discovery against Babesia microti by natural compounds: An extensive computational drug design approach. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.13, 1222913 (2023).

Akash, S. et al. Development of new bioactive molecules to treat breast and lung cancer with natural myricetin and its derivatives: A computational and SAR approach. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.12, 952297 (2022).

Mehmood, A. et al. Bringing structural implications and deep learning-based drug identification for KRAS mutants. J. Chem. Inf. Model.61(2), 571–586 (2021).

Tripathi, M. K. et al. Fundamentals of Molecular Modeling in drug Design. In Computer Aided Drug Design (CADD): From Ligand-Based Methods to Structure-Based Approaches 125–155 (Elsevier, 2022).

Yadav, M. K. et al. Predictive modeling and therapeutic repurposing of natural compounds against the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.41, 1–13 (2022).

Akash, S. et al. Mechanistic inhibition of gastric cancer-associated bacteria Helicobacter pylori by selected phytocompounds: A new cutting-edge computational approach. Heliyon9(10), e20670 (2023).

Ramlal, A. et al. From molecules to patients: The clinical applications of biological databases and electronic health records. In Translational Bioinformatics in Healthcare and Medicine 107–125 (Academic Press, 2021).

Rose, P. W. et al. The RCSB protein data bank: Integrative view of protein, gene and 3D structural information. Nucleic Acids Res.45, gkw1000 (2016).

Shah, A. A. et al. Structure-based virtual screening, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and metabolic reactivity studies of quinazoline derivatives for their anti-EGFR activity against tumor angiogenesis. Curr. Med. Chem.31(5), 595 (2023).

Maestro, S. Maestro Vol. 2020 (Schrödinger, LLC, 2020).

Release, S. Schrödinger Suite 2017-1 Protein Preparation Wizard (Epik, Schrödinger, LLC, 2017).

Jacobson, M. P. et al. A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform.55(2), 351–367 (2004).

Karwasra, R. et al. Macrophage-targeted punicalagin nanoengineering to alleviate methotrexate-induced neutropenia: A molecular docking, DFT, and MD simulation analysis. Molecules27(18), 6034 (2022).

Shelley, J. C. et al. Epik: A software program for pK a prediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des.21, 681–691 (2007).

Søndergaard, C. R. et al. Improved treatment of ligands and coupling effects in empirical calculation and rationalization of pKa values. J. Chem. Theory Comput.7(7), 2284–2295 (2011).

Jorgensen, W. L. & Tirado-Rives, J. The OPLS [optimized potentials for liquid simulations] potential functions for proteins, energy minimizations for crystals of cyclic peptides and crambin. J. Am. Chem. Soc.110(6), 1657–1666 (1988).

Shivakumar, D. et al. Prediction of absolute solvation free energies using molecular dynamics free energy perturbation and the OPLS force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput.6(5), 1509–1519 (2010).

QikProp, S. Schrödinger Release 2017 (Maestro LLC, 2017).

Release, S. LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2017 (2017).

Release, S. Receptor Grid Generation (Schrödinger, LLC, 2019).

Release, S., Glide: Schrödinger. LLC, NY (2020)

Kaul, T. et al. Probing the effect of a plus 1 bp frameshift mutation in protein-DNA interface of domestication gene, NAMB1, in wheat. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.38(12), 3633–3647 (2019).

Lipinski, C. A. Lead-and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol.1(4), 337–341 (2004).

Chandrasekaran, B. et al. Computer-aided Prediction of Pharmacokinetic (ADMET) Properties. In Dosage form Design Parameters 731–755 (Elsevier, 2018).

Bowers, K. J. et al. Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing (2006).

Mark, P. & Nilsson, L. Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. A105(43), 9954–9960 (2001).

McDonald, I. NpT-ensemble Monte Carlo calculations for binary liquid mixtures. Mol. Phys.23(1), 41–58 (1972).

Genheden, S. & Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov.10(5), 449–461 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-13).

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, with project No: TU-DSPP-2024-13.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, funding, analysis, visualisation, writing the first draft, supervising the whole research project and refining the manuscript for publication; Ahad Amer Alsaiari. analysis, visualisation, writing the first draft, supervising the whole research project and refining the manuscript for publication; Fawaz M. Almufarriji. analysis, visualisation, writing the first draft, supervising the whole research project and refining the manuscript for publication; Ali Hazazi. Conceptualisation, analysis, visualisation, writing the first draft; Daniyah A. Almarghalani. Data Collection, Analysis, visualisation, writing the first draft, extensive editing; Maha Mahfouz Bakhuraysah. Data preparation, processing, analysis, figure conversion and editing first draft; Amani A. Alrehaili. Reviewed and edited the manuscript and helped to revise it; Shatha M. Algethami. Data Collection, Analysis, visualisation, writing the first draft, extensive editing; Khulood A. Almehmadi. visualisation, writing the first draft, extensive editing; Fayez Saeed Bahwerth. Conceptualisation, analysis, visualisation, writing the first draft, supervising the whole research project and refining the manuscript for publication; Mohammed Ageeli Hakami.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsaiari, A.A., Almufarriji, F.M., Hazazi, A. et al. Multitargeted docking approach reveals droxidopa against DNA replication and repair-related protein of cervical cancer. Sci Rep 14, 24301 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72770-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72770-9