Abstract

The association of health-related productivity loss (HRPL) with social isolation and depressive symptoms is not well studied. We aimed to examine the association of social isolation and depressive symptoms with productivity loss. Data on employed adults aged 21 years and above were derived from the Population Health Index (PHI) study conducted by the National Healthcare Group (NHG) on community-dwelling adults, residing in the Central and Northern residential areas of Singapore. The severity of depressive symptoms and social isolation were assessed using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Lubben Social Network Scale-6 (LSNS-6) respectively. Productivity loss was assessed using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI). We used Generalised Linear Models, with family gamma, log link for the analysis. Models were adjusted for socio-demographic variables (including age, gender, ethnicity, employment status, housing type) and self-reported chronic conditions (including the presence of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia). There were 2,605 working (2,143 full-time) adults in this study. The median reported percentage of unadjusted productivity loss was 0.0%, 10.0% and 20.0% for participants with social isolation, depressive symptoms, and both, respectively. In the regression analysis, mean productivity loss scores were 2.81 times (95% Confidence Interval: 2.12, 3.72) higher in participants with depressive symptoms than those without. On the other hand, social isolation was not found to be associated with productivity loss scores (1.17, 95% Confidence Interval: 0.96, 1.42). The interaction term of depressive symptoms with social isolation was statistically significant, with an effect size of 1.89 (95% Confidence Interval: 1.04, 3.44). It appeared that productivity loss was amplified when social isolation and depressive symptoms were concomitant. Our results suggested significant associations of social isolation and depressive symptoms with productivity loss. These findings highlighted the potential impact of social isolation and depressive symptoms on work performance and drew attention to the importance of having a holistic work support system that promotes social connectedness, mental wellbeing and work productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) was estimated to be 3.2% in 2021, an increase of 27.6% from 2020 due the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, with reasons attributed to reduced mobility and social interactions1. The Singapore Mental Health Study conducted in 2016 reported the 12-month and lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder to be 2.3% and 6.3%, respectively2. The actual Singapore prevalence of depression is likely higher accounting for underdiagnoses and underreporting. Studies have cited reasons for low prevalence figures such as a tendency to underreport negative health outcomes and mood problems among Asian populations due to stigmatisation3,4,5. It was additionally found that depressive symptoms among Asians were more likely to present as somatic symptoms and a reduction in willingness to socialise, and hence less likely identified as depressive disorders6. In 2021, it was reported that Singapore residents were more likely to seek help from informal support network comprising of family and friends (69.1%) than from healthcare providers (58.3%), highlighting the importance of building strong social networks and social interactions in the backdrop of the rising prevalence of depression7.

The lack of social relationships and a poor social network indicates the extent to which an individual is socially isolated8. There were 26.3% of adults identified to be isolated according to the Population Health Index (PHI) survey, conducted in Singapore in 20169. With numerous social restrictions put in place at the height of COVID-19, associations between social isolation and depression have been identified across diverse groups10,11,12,13. The impact of social isolation and depressive symptoms appears deleterious as individuals with both were found to have poorer health outcomes, reporting worse depressive symptoms, lower remission rates and poorer social function compared to those with depressive symptoms but higher perceived social support14. While associations were found between work disability, depression and poor social functioning15,16,17, the association of workplace productivity with social isolation and depressive symptoms is not well studied.

Health-related productivity loss (HRPL) is described as missed time from work (absenteeism) and reduced performance while at work (presenteeism) as a result of diseases or health risk18. HRPL can provide information on the indirect economic burden of health problems. It allows for a comprehensive evaluation of both direct and indirect costs of a medical condition or benefit from intervention. Productivity loss studies have been previously carried out in Asian populations, with levels of presenteeism reported to be higher than that of absenteeism levels19,20,21. For instance, a study on depression-related productivity loss revealed presenteeism costs to be 10 times higher than absenteeism costs in South Korean21. Other Asian studies conducted in Sri Lanka and Malaysia had estimated productivity loss in terms of workdays lost and percentage of work time lost respectively, citing income, physical health, stress levels and mood as common factors for productivity loss [20; 21]. The economic burden of mental disorders in Singapore is well recognised and it has been estimated to approximately cost S$3,900 per person per year22. On the other hand, socially isolated individuals were three times more likely to experience occupational burnout, which occupational burnout is linked to absenteeism and poorer work performance23. However, it is unknown if social isolation and depressive symptoms impact workplace productivity.

Based on the Conservation of Resources theory, individuals experience stress when resources are jeopardised or lost. Resources consist of material possessions (objects), relationships or living circumstances (conditions), self-efficacy (personal characteristics), and capacity (energies)24,25. Depressive symptoms have been reported to be associated with reduced motivation to work (an example of intrinsic resource) and reduced social support (an example of extrinsic resource)26,27. Similarly, social isolation was found to be associated with reduced motivation and reduced social support28,29. We hypothesised that working adults reporting both social isolation and depressive symptoms would incur more HRPL due to the concomitant depletion of intrinsic and extrinsic resources. Hence, we aimed to examine the association of social isolation and depressive symptoms with HRPL. These findings could potentially highlight the importance of building social and mental health support at the workplace.

Methods

Study design

Study data were derived from the Population Health Index (PHI) Survey study initiated by the National Healthcare Group (NHG), one of the regional healthcare clusters of Singapore, to establish a better understanding of current health states of residents living in the Central and Northern residential areas of Singapore. The PHI study was approved by the ethics review committee of the National Healthcare Group (NHG) Domain Specific Review Board (Reference Number: 2015/00269), and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants after they were informed of the study objectives and confidentiality of the collected data was maintained throughout the conduct of the study.

The specific data used in this study were taken from the Phase 2 PHI, a cross-sectional survey conducted between November 2018 and June 2019. The survey questionnaire was administered by trained interviewers via face-to-face interviews among community-dwelling adults aged ≥ 21 years and residing in the Central and Northern regions of Singapore. The sampling design and participant recruitment processes had been described elsewhere30.

Participants were included in this analysis if they met the following two criteria: (1) employed (either full-time or part-time), and (2) cognitively sound and responded to the survey independently. There were no missing data for any variables.

Measures

The PHI questionnaire consisted of socio-demographics, lifestyle, medical history, and a set of validated measures. The following socio-demographic characteristics and self-reported chronic conditions from the survey were used as covariates in this study to account for any potential confounding effects: age, gender (female or male), ethnicity (Chinese, Malay, Indian or Others), employment status (full-time or part-time), housing type (Public 1–2 room, Public 3-room, Public 4-room, or Public 5-room and bigger and private properties), region of residence (residing in Central or Northern Singapore) and presence of self-reported diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Explanatory variables

Depressive symptoms

The severity of depressive symptoms was assessed by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is a well-validated tool that was developed to make symptom-based diagnosis of depression and additionally grade the severity of depressive symptoms31. The PHQ-9 has shown good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) in this study. Each question item was scored on a 4-point ordinal scale and an aggregate depressive symptom score was derived from summing the scores of each item. A higher score indicated greater severity of depressive symptoms. Participants with a score ranging from 0 to 4 indicated no depressive symptoms, 5–9 mild depressive symptoms, 10–14 moderate depressive symptoms, 15–19 moderately-severe depressive symptoms, and 20–27 severe depressive symptoms31. For this study, depressive symptoms were treated as a binary variable with scores 0–4 indicative of “without depressive symptoms” and scores 5–27 indicative of “with depressive symptoms”.

Social isolation

The magnitude of social isolation was estimated by the Lubben Social Network Scale-6 (LSNS-6). The LSNS-6 is a validated tool which presents a composite scale for measuring social connectedness and examining the relationship of social connectedness to health outcomes32. The LSNS-6 consists of a set of three questions that measure social connectedness with family members and another set of three questions that measure social connectedness with friends. The LSNS-6 has two subscales and both have demonstrated good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78 and 0.76 respectively) in this study. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale, and the scores were added up to form a total score. Higher scores indicated greater levels of social connectedness and lower risk of social isolation. A score of 0–12 indicated isolated, 13–16 high risk of social isolation, 17–20 moderate risk of social isolation, and 21–30 low risk of social isolation32. It has been suggested that a higher cut-off score may be more appropriate to identify social isolation in Asian populations due to greater reliance on social relationships33,34. For this study, participants with a score ranging from 17 to 30 was classified as “without social isolation” and those with a score of 0 to 16 was deemed as “socially isolated”.

Outcome variable

The loss of workplace productivity due to health reasons, or more commonly known as HRPL, consists of workplace health-related absenteeism and presenteeism. HRPL was measured by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI). The WPAI was developed as a quantitative measure that measures work impairment as distinct from impairment in other activities of daily living35. The WPAI has been previously validated to measure the general health impact of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and major depressive disorder36,37. The test-retest reliability of the WPAI has been demonstrated in the Singapore population38. The WPAI consists of six questions, of which the number of work days missed and the degree of health-related productivity loss (using a 0 to 10 Visual Analogue Scale) are measured. Absenteeism is defined as missed time from work (percentage of work time missed due to health problems = \(\:\frac{Hours\:absent\:due\:to\:health}{\left[Hours\:absent\:due\:to\:health+Actual\:worked\:hours\right]}\:\times\:100\)). Presenteeism is defined as reduced performance while at work (percentage of work impaired due to health problems = \(\:\left(\frac{Impairment\:rating}{10}\right)\:\times\frac{Actual\:worked\:hours}{\left[Hours\:absent\:due\:to\:health+Actual\:worked\:hours\right]}\:\times\:100\)) on a 10-point rating scale39. To derive the total HRPL (with a score ranging from 0 to 100), we calculated the percentage of total work impaired due to health problems by summing the percentage of absenteeism and presenteeism.

Statistical analysis

Majority of participants reported zero levels of presenteeism and absenteeism, and the data were characterized by non-negative, continuous values and right skewed distributions. To ascertain differences in HRPL among working adults, we used Generalised Linear Model (GLM), with family gamma, log link for the analysis due to the known distribution characteristics of our outcome. The coefficients were exponentiated to describe the arithmetic mean ratios (ratios of mean HRPL) between the groups, as we were interested in comparing the relative differences in mean HRPL. A mean ratio of > 1 indicates that the comparator group has a higher mean value than the reference group; a mean ratio of < 1 indicates that the comparator group has a lower mean value than the reference group; and a mean ratio = 1 indicates that the comparator group has a mean value equivalent to that of the reference group). In the first model, social isolation and depressive symptoms were both added as independent variables to determine their effects on HRPL respectively. In the second model, we tested for significant interactions between the presence of social isolation and depressive symptoms, with productivity loss. To further understand the interaction term, a simple slopes analysis was conducted. Both models were adjusted for socio-demographic variables (including age, gender, ethnicity, employment status, housing type) and self-reported chronic conditions (including the presence of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia). Geographical region was controlled for, to account for possible geographical differences in socio-economic status40.

Results

Socio-demographics

Among the 4,005 participants who were surveyed for the PHI study, 2,605 employed participants (65.0%) were identified for this analysis on working adults.

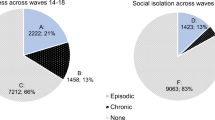

Table 1 presents the socio-demographics of the 2,605 participants. Of which 1,273 (48.9%) were female, the mean age was 47.3 years and 30.9% were aged below 40. There were 727 (27.9%) participants having at least one self-reported chronic condition. Most of the participants were Chinese (73.4%), living in public 4-room flat and bigger (69.7%), and working full-time (82.3%). More than half (54.1%) of participants were residing in Northern Singapore. There were 1,137 participants (43.6%) identified to be at high risk of social isolation, 130 participants (5.0%) had mild-severe depressive symptoms, and 82 participants (3.1%) experienced co-occurring social isolation and depressive symptoms.

Unadjusted productivity loss

The median percentage of productivity loss reported due to missed work days (absenteeism) was 0.0% for participants with social isolation, depressive symptoms and both respectively (Fig. 1). Presenteeism appeared to be a bigger component of HRPL, with the median percentage of work productivity affected while at work of 0.0%, 5.0% and 10.0% for participants with social isolation, depressive symptoms, and both, respectively. The median reported percentage of overall HRPL was 0.0%, 10.0% and 20.0% for participants with social isolation, depressive symptoms, and both, respectively. The mean percentage of productivity loss is presented in the Supplementary Fig. 1 (Additional File 1).

Association of productivity loss with social isolation and depressive symptoms

The results from multiple linear regression analyses are shown in Table 2. Mean HRPL scores were up to 2.81 times (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 2.12, 3.72) higher in participants with depressive symptoms than those without. On the other hand, social isolation was not found to be associated with HRPL scores (1.17, 95% CI 0.96, 1.42).

Upon including the interaction term in the second model, we observed that participants with depressive symptoms had 1.81 times (95% CI 1.08, 3.06) higher HRPL scores as compared to those without. Socially isolated participants were not found to be associated with HRPL scores (1.14, 95% CI 0.93, 1.39). The interaction between social isolation and depressive symptoms was statistically significant (p-value = 0.037), with an effect size of 1.89 (95% CI 1.04, 3.44). From the simple slopes analysis (Fig. 2a and b), the presence of both high risk of social isolation and mild-severe depressive symptoms had the highest levels of HRPL (24.23, 95% CI 17.47, 30.98).

Simple slope analysis of the interaction between social isolation and depressive symptoms on HRPL, with 95% Confidence Intervals. (a) Social isolation as the independent variable and depressive symptoms as the moderating variable. (b) Depressive symptoms as the moderating variable and social isolation as the independent variable.

From both GLM results, depressive symptoms were associated with productivity loss among all working adults. We did not find evidence for the association between social isolation and productivity loss. The non-exponentiated coefficients (See Supplementary Table 1, Additional File 1) present similar trends and the positive interaction term suggest incremental marginal effects on productivity loss.

Discussion

Main findings

In this multi-ethnic community-dwelling working adult population, we observed association between workplace productivity loss and social isolation concomitant with depressive symptoms. The interaction term suggested that HRPL was amplified when both were co-occuring, which aligned with poorer health outcomes (e.g., remission, survival, biological and functional outcomes) that were previously reported among socially isolated individuals with depressive symptoms14,41,42. The simple slopes analysis has demonstrated a positive and significant interaction where HRPL was greater for those who had depressive symptoms and were at a higher risk of social isolation. Conversely, participants with low-moderate risk of isolation and high risk of isolation similarly had low levels of HRPL if they had no depressive symptoms. We observed that the impact of depressive symptoms on productivity loss was likely moderated by the risk of social isolation. The Conservation of Resources theory conferred that individuals mitigate the loss of resources either by tapping on other existing resources or by acquiring additional resources24,25. It is likely that individuals with depressive symptoms coped with the loss of intrinsic resources by expanding on their social relationships. The lack of social relationships led to a disequilibrium in resources, potentially culminating in stress and, consequently, diminished work productivity. Our findings highlighted the potential impact of social isolation and depressive symptoms on work performance and drew attention to the importance of having a holistic work support system that promotes social connectedness, mental wellbeing and work productivity, especially for individuals who are experiencing psychological distress.

Presence of depressive symptoms was associated with productivity loss, however, the same was not observed for the presence of social isolation. Our findings suggested that psychological symptoms and experiences potentially had a stronger relationship with work productivity than social connectedness. This observation was echoed by two Asian studies which cited stress and depressed mood as the top reasons for presenteeism20,21. The levels of presenteeism among socially isolated participants in this study (mean of 5.9%) was lower than another Malaysian study which reported an average of 20.3% among high-income earners20. There is a lack of observational studies examining the association between social isolation and the loss of intrinsic resources. In a recent experimental study conducted in 2023 among Caucasians, Stijovic et al. observed a significant association between acute social isolation and reduced motivation to engage in regular activities29. However, our study did not observe any association between social isolation and productivity loss, suggesting that socially isolated participants in our population were likely less impacted by the reduced motivation to work, hence largely had remained productive at work. Differences in study design (experimental versus natural observational study), duration of social isolation (prolonged social isolation as compared to acute social isolation), preference for social isolation (intentional isolation as opposed to circumstantial isolation) and demographics (Western population in comparison to an Asian population) could have led to a difference in observations. Hence, further studies will be needed to explore the nuances of social isolation and their relationships with work productivity in Asian populations. The interplay of social isolation and depressive symptoms warrants future research and intervention strategies targeted at individuals with depressive symptoms who are at risk of social isolation.

Additionally, females in this study were observed to be associated with productivity loss. This may be explained by gender differences in occupations and comorbidities43. Ethnicity was also observed to be associated with productivity loss (Malay ethnicity was significantly associated with productivity loss compared to Chinese ethnicity). It could potentially be due to a higher prevalence of chronic conditions among the Malay ethnicities2, hence strengthening the association with productivity loss. Being employed full-time (reference: employed part-time) was found to be associated with productivity loss, probably because those working full-time were subjected to longer working hours, hence reporting greater presenteeism44. With entitlement to more paid sick leaves, there is also a tendency for full-timer employees to take additional days off from work45. Those of a younger age was found to be associated with productivity loss in this study. This phenomenon corroborated with the literature where the work performance of older workers outdoes that of the younger workers, due to reasons such as greater job experience and self-assurance to perform better at work46. Residents residing in the Northern region were younger (mean age of 45.5 versus 49.4) and more were employed full-time (84.7% versus 79.4%), likely explaining for their higher productivity loss. Lastly, having dyslipidaemia incurred greater productivity loss, likely due to the higher risks of cardiovascular diseases, impacting productivity47. It appeared that there were multiple factors associated with productivity loss, and further sub-group analyses should be done given a larger study population in the future.

In this study, we observed that participants with social isolation and depressive symptoms were 10.0% less productive at work due to their health problems in the past seven days (presenteeism). We postulate that the association between poor mental health and presenteeism has driven HRPL in our study. In a Singaporean study, it was estimated that individuals with depressive symptoms and/or anxiety had their productivity at work reduced by 40.0%48. In another Malaysian study, mental health was reported to be a predictor of presenteeism, and physical health as a predictor of absenteeism20. Our findings underscore the need to focus more efforts on enhancing at-work productivity and putting in place policies to encourage employees to take time-off from work for their mental health when needed.

Strengths and limitations

As a population-based study, the primary strength of this study was its representativeness of the population in Central and Northern regions of Singapore. Singapore is a multi-ethnic Asian population and the associations presented in this study are likely observable in the rest of Singapore and potentially other the Asian countries, although the generalisability of the study findings may be constrained by the extent of socioeconomic differences across geographical boundaries40. Other strengths of this study included the use of standardised questionnaire. This study was able to evaluate multiple factors associated with productivity loss, allowing for sub-group analyses and adjustment for various socio-economic factors. Lastly, the magnitude of productivity loss was based on self-reported data with a recall period of 7 days. Although the main outcome of interest was subjected to recall errors, the extent of recall bias was possibly minimised by the short recall period.

This study, however, is not without limitations. The study design was a cross-sectional study, and we were unable to ascertain the temporal sequence of the explanatory factors and main outcome of interest. There had been a 5-year Finnish cohort study that had established MDD as a predictor of poor work outcomes among psychiatric subjects15,16,17. In another 12-year American cohort study among older adults, it was found that depressive symptoms predicted social isolation, while social isolation was not a predictor of depressive symptoms49. The temporal sequence of depressive symptoms, social isolation and work productivity loss altogether need further investigation. Our study only considered productivity loss at the workplace, whereas the WPAI measure also measured activity impairment in unpaid work activities35. As this study was a cross-sectional study, the responsiveness assessed by measuring changes in the WPAI responses was not done. Hence, we did not test for test-retest reliability, although it has been shown to be reliable in the Singapore population38. Another study limitation was that we did not collect information on the number of chronic conditions and presence of other comorbidities, where multimorbid depression is known to be associated with poorer health-related outcomes50. However, we have attempted to account for the three most common chronic conditions in Singapore, namely diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia. Additionally, the prevalence of depressive symptoms reported in our study was possibly underreported due to existing stigma. Hence, the actual productivity loss associated with depressive symptoms could be much higher. As this study only included working adults, those that were non-employed were excluded from the analysis. It is unclear if 40.7% of those socially isolated and 49.8% of those with depressive symptoms were not employed in this study due to social isolation and depressive symptoms. Although this study did not conduct qualitative interviews to further investigate the psychosocial reasons for productivity loss, existing qualitative findings suggest that a work-culture which values employees’ well-being, alongside supportive peers and employers, and assisted return-to-work arrangements do influence return-to-work outcome of employees with depression51. Further research could be a cohort study with mixed-methods approach to better understand the relationship between depressive symptoms, social isolation, and workplace productivity loss.

Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the association of social isolation and depressive symptoms, with workplace productivity loss in community-dwelling working adult population in Singapore. Our results corroborated with the existing literature that have shown associations between poorer work adjustments and absenteeism, with social isolation and depressive symptoms15,16,17. Our findings on the association of social isolation and depressive symptoms with productivity loss (productivity loss of up to 1.89 times more) echoed the importance of managing social isolation and depressive symptoms at the workplace. More structural support (workplace policies) and social support (from peers and employers) are needed for the promotion of workplace productivity and well-being.

Conclusion

This study observed an association between productivity loss and depressive symptoms, and the association was stronger when working adults were simultaneously reported to be socially isolated. We observed a greater magnitude of reduced productivity while at work as compared to missed time from work. With the increasing focus on well-being at the workplace, our findings reiterate the importance of building a supportive work environment and forging strong social networks, as mental well-being and work productivity are closely interconnected.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-2019

- PHI:

-

Population Health Index

- HRPL:

-

Health-related productivity loss

- NHG:

-

National Healthcare Group

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- LSNS-6:

-

Lubben Social Network Scale-6

- WPAI:

-

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire

- GLM:

-

Generalised linear model

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Collaborators, C. M. D. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 398(10312), 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 (2021).

Subramaniam, M. et al. Tracking the mental health of a nation: Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in the second Singapore mental health study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr Sci.29, e29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000179 (2019).

Lauber, C. & Rossler, W. Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. Int. Rev. Psychiat. 19(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701278903 (2007).

Kawi, J., Reyes, A. T. & Arenas, R. A. Exploring pain management among Asian immigrants with chronic pain: Self-management and resilience. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 21(5), 1123–1136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0820-8 (2019).

Kalibatseva, Z. & Leong, F. T. Depression among Asian americans: Review and recommendations. Depress. Res. Treat.2011, 320902. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/320902 (2011).

Im, E. O., Yang, Y. L., Liu, J. & Chee, W. The association of depressive symptoms to sleep-related symptoms during menopausal transition: Racial/ethnic differences. Menopause. 27(11), 1315–1321. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001611 (2020).

Epidemiology & Disease Control Division and Policy, R. S. G., Ministry of Health and Health Promotion Board. National Population Health Survey 2021 (2021).

Griffin, J. The Lonely Society? (The Mental Health Foundation, 2010).

Ge, L., Yap, C. W., Ong, R. & Heng, B. H. Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLoS One. 12(8), e0182145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182145 (2017).

Purssell, E., Gould, D. & Chudleigh, J. Impact of isolation on hospitalised patients who are infectious: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Open.10(2), e030371. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030371 (2020).

Luo, M., Guo, L., Yu, M., Jiang, W. & Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res.291, 113190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190 (2020).

Saulle, R. et al. School closures and mental health, wellbeing and health behaviours among children and adolescents during the second COVID-19 wave: A systematic review of the literature. Epidemiol. Prev.46(5–6), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.19191/EP22.5-6.A542.089 (2022) ((Chiusura della scuola e salute mentale, benessere e comportamenti correlati alla salute in bambini e adolescenti durante la seconda ondata di COVID-19: una revisione sistematica della letteratura.)).

Silva, C. et al. Depression in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.71(7), 2308–2325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18363 (2023).

Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R. & Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 18(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5 (2018).

Holma, I. A., Holma, K. M., Melartin, T. K., Rytsala, H. J. & Isometsa, E. T. A 5-year prospective study of predictors for disability pension among patients with major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand.125(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01785.x (2012).

Rytsala, H. J. et al. Determinants of functional disability and social adjustment in major depressive disorder: a prospective study. J. Nerv. Ment Dis.194(8), 570–576. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000230394.21345.c4 (2006).

Rytsala, H. J. et al. Predictors of long-term work disability in major depressive disorder: A prospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand.115(3), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00878.x (2007).

Mitchell, R. J. & Bates, P. Measuring health-related productivity loss. Popul. Health Manag. 14(2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2010.0014 (2011).

Evans-Lacko, S. & Knapp, M. Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: Absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries. Soc. Psychiat Psychiatr Epidemiol.51(11), 1525–1537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1278-4 (2016).

Wee, L. H. et al. Anteceding factors predicting absenteeism and presenteeism in urban area in Malaysia. BMC Public. Health. 19(Suppl 4), 540. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6860-8 (2019).

Fernando, M., Caputi, P. & Ashbury, F. Impact on employee productivity from presenteeism and absenteeism: Evidence from a multinational firm in Sri Lanka. J. Occup. Environ. Med.59(7), 691–696. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001060 (2017).

Abdin, E. et al. The economic burden of mental disorders among adults in Singapore: Evidence from the 2016 Singapore mental health study. J. Ment Health. 32(1), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1952958 (2023).

Boland, L. L., Mink, P. J., Kamrud, J. W., Jeruzal, J. N. & Stevens, A. C. Social support outside the workplace, coping styles, and burnout in a cohort of EMS providers from Minnesota. Workplace Health Saf.67(8), 414–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079919829154 (2019).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol.44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513 (1989).

Hobfoll, S. E. The Ecology of Stress (Taylor & Francis, 1988).

Grav, S., Hellzen, O., Romild, U. & Stordal, E. Association between social support and depression in the general population: The HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. J. Clin. Nurs.21(1–2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03868.x (2012).

Björklund, C., Jensen, I. & Lohela-Karlsson, M. Is a change in work motivation related to a change in mental well-being? J. Voc Behav.83(3), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.09.002 (2013).

Gable, S. L. & Bedrov, A. Social isolation and social support in good times and bad times. Curr. Opin. Psychol.44, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.027 (2022).

Stijovic, A. et al. Homeostatic regulation of energetic arousal during acute social isolation: Evidence from the lab and the field. Psychol. Sci.34(5), 537–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976231156413 (2023).

Ge, L., Heng, B. H. & Yap, C. W. Understanding reasons and determinants of medication non-adherence in community-dwelling adults: A cross-sectional study comparing young and older age groups. BMC Health Serv. Res.23(1), 905. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09904-8 (2023).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med.16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Lubben, J. et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 46(4), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.4.503 (2006).

Chang, Q., Sha, F., Chan, C. H. & Yip, P. S. F. Validation of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6) and its associations with suicidality among older adults in China. PLoS One. 13(8), e0201612. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201612 (2018).

Chang, Q., Chan, C. H. & Yip, P. S. F. A meta-analytic review on social relationships and suicidal ideation among older adults. Soc. Sci. Med.191, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.003 (2017).

Reilly, M. C. Development of the work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) Questionnaire (Reilly Associates, 2008).

Trivedi, M. H. et al. Increase in work productivity of depressed individuals with improvement in depressive symptom severity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 170(6), 633–641. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020250 (2013).

Zhang, W. et al. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire–general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther.12(5), R177. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3141 (2010).

Phang, J. K. et al. Validity and reliability of Work Productivity and Activity Impairment among patients with axial spondyloarthritis in Singapore. Int. J. Rheum. Dis.23(4), 520–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13801 (2020).

Boles, M., Pelletier, B. & Lynch, W. The relationship between health risks and work productivity. J. Occup. Environ. Med.46(7), 737–745. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000131830.45744.97 (2004).

Earnest, A. et al. Derivation of indices of socioeconomic status for health services research in Asia. Prev. Med. Rep.2, 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.04.018 (2015).

Spaderna, H. et al. Role of depression and social isolation at time of waitlisting for survival 8 years after heart transplantation. J. Am. Heart Assoc.https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.007016 (2017).

Hafner, S. et al. Social isolation and depressed mood are associated with elevated serum leptin levels in men but not in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 36(2), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.009 (2011).

Laaksonen, M. et al. Gender differences in sickness absence–the contribution of occupation and workplace. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 36(5), 394–403. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.2909 (2010).

Lee, D. W., Lee, J., Kim, H. R. & Kang, M. Y. Association of long working hours and health-related productivity loss, and its differential impact by income level: A cross-sectional study of the Korean workers. J. Occup. Health. 62(1), e12190. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12190 (2020).

Ahn, T. & Yelowitz, A. Paid sick leave and absenteeism: The first evidence from the US. SSRN, 2740366. (2016).

Viviani, C. A. et al. Productivity in older versus younger workers: A systematic literature review. Work. 68(3), 577–618. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-203396 (2021).

Ferrara, P., Di Laura, D., Cortesi, P. A. & Mantovani, L. G. The economic impact of hypercholesterolemia and mixed dyslipidemia: A systematic review of cost of illness studies. PLoS One. 16(7), e0254631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254631 (2021).

Chodavadia, P., Teo, I., Poremski, D., Fung, D. S. S. & Finkelstein, E. A. Prevalence and economic burden of depression and anxiety symptoms among Singaporean adults: Results from a 2022 web panel. BMC Psychiat. 23(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04581-7 (2023).

Luo, M. Social isolation, loneliness, and depressive symptoms: A twelve-year population study of temporal dynamics. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci.78(2), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbac174 (2023).

Yeung, Y. L. et al. Associations of comorbid depression with cardiovascular-renal events and all-cause mortality accounting for patient reported outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A 6-year prospective analysis of the Hong Kong diabetes register. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1284799. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1284799 (2024).

Corbiere, M. et al. Union perceptions of factors related to the return to work of employees with depression. J. Occup. Rehabil. 25(2), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9542-5 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by National Healthcare Group Pte Ltd in the form of salaries for all authors. The funder had no role in / influence on study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.Y.H analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. W.Y. interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. L.G. conceived the study and revised the manuscript. C.W.Y. conceived the study and revised the manuscript. M.J.P. conceived the study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The PHI study was approved by the ethics review committee of the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (Reference Number: 2015/00269). Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants after they were being informed about the study objectives.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants after they were being informed about the study objectives.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ha, J.W.Y., Yip, W., Ge, L. et al. Association of social isolation and depressive symptoms with workplace productivity loss in a multi-ethnic Asian study. Sci Rep 14, 22145 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73272-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73272-4