Abstract

Minimal change disease (MCD) is a common cause of nephrotic syndrome. Due to its rapid progression, early detection is essential; however, definitive diagnosis requires invasive kidney biopsy. This study aims to develop non-invasive predictive models for diagnosing MCD by machine learning. We retrospectively collected data on demographic characteristics, blood tests, and urine tests from patients with nephrotic syndrome who underwent kidney biopsy. We applied four machine learning algorithms—TabPFN, LightGBM, Random Forest, and Artificial Neural Network—and logistic regression. We compared their performance using stratified 5-repeated 5-fold cross-validation for the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC). Variable importance was evaluated using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method. A total of 248 patients were included, with 82 cases (33%) were diagnosed with MCD. TabPFN demonstrated the best performance with an AUROC of 0.915 (95% CI 0.896–0.932) and an AUPRC of 0.840 (95% CI 0.807–0.872). The SHAP methods identified C3, total cholesterol, and urine red blood cells as key predictors for TabPFN, consistent with previous reports. Machine learning models could be valuable non-invasive diagnostic tools for MCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Minimal change disease (MCD) is one of the primary causes of nephrotic syndrome in adults worldwide1. Unlike most other causes of nephrotic syndrome, which progress over weeks to months, MCD is characterized by a rapid onset worsening from a few days to 1–2 weeks. Approximately 25–35% of MCD patients develop acute kidney injury, and in severe cases, urgent hemodialysis may be required2,3. Due to its rapid onset, early diagnosis and timely treatment are crucial for a good prognosis in MCD patients. The diverse causes of nephrotic syndrome in adults make diagnosing MCD through general clinical tests challenging, thus requiring definitive diagnosis via kidney biopsy. However, kidney biopsy has several contraindications and carries risks of severe complications like bleeding, arteriovenous fistulas, and infections4,5. Furthermore, since it takes time to obtain biopsy results, the condition may rapidly worsen if immediate treatment cannot be administered during this period. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore non-invasive and practical diagnostic methods for MCD.

The potential for diagnosing MCD before or without kidney biopsy through non-invasive diagnostic approaches using blood and urine biomarkers has been discussed. Serum IL-12p40, urinary CD80, urinary fatty acid-binding protein 4, and urinary epidermal growth factor are among the biomarkers expected to distinguish MCD from other diseases6,7,8,9,10. However, these biomarkers cannot yet be measured in general medical facilities without advanced equipment, so their clinical utility remains uncertain. Currently, no single parameter measured in clinical settings stands out as a strong disease-specific predictor11,12,13. Therefore, it is crucial to combine various parameters for a comprehensive assessment when diagnosing MCD.Developing predictive models using clinically measurable parameters could be beneficial, but research on such models for diagnosing MCD is limited14,15,16. Previous studies on diagnostic predictive models have employed logistic regression. While logistic regression is a classical statistical model that assumes linear relationships and excels in interpretability, its predictive performance may have limitations.

Machine learning, a subset of artificial intelligence, can model non-linear relationships and analyze complex higher-order interactions, potentially improving predictive performance17. Therefore, machine learning is widely used to analyze large volumes of clinical data obtained from electronic medical records and is beneficial in developing predictive models18,19. In nephrology, machine learning has been applied to various predictive tasks, such as the onset of acute kidney injury20, the renal prognosis of chronic kidney disease21, the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy22, and the onset of dialysis hypotension23. However, the utility of machine learning in predicting the diagnosis of MCD remains unknown.

This study aims to develop diagnostic predictive models for MCD in adult nephrotic syndrome patients based on demographic characteristics, blood tests, and urine tests that are easily accessible in clinical settings. Our secondary objective is to demonstrate that machine learning models can provide a non-invasive, highly accurate, and reliable approach for diagnosing MCD compared to traditional statistical models.

Methods

Study design and study participants

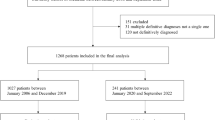

This study is a retrospective study involving patients at St. Marianna University Hospital, a tertiary care hospital in Japan. The data were collected from the electronic medical records of the hospital. The study included all nephrotic syndrome patients who underwent native kidney biopsy at St. Marianna University Hospital between January 1, 2006, and March 31, 2024. Nephrotic syndrome was defined as having ≥ 3.5 g/day or ≥ 3.5 g/g Cr of urinary protein and ≤ 3.0 mg/dL of serum albumin and was clinically diagnosed by nephrologists before kidney biopsy. The patients were excluded if they met any criteria: (a) under 18 years old, (b) the definitive diagnosis was unclear, or (c) multiple definitive diagnoses, not a single one. The details of patient selection are shown in Fig. 1.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. It was approved by the St. Marianna University Hospital Institutional Review Board (approval number: 6450), which allowed for the analysis of patient-level data with a waiver of informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with TRIPOD + AI statement24, guidelines for developing and reporting machine-learning predictive models in biomedical research: a multidisciplinary view25.

Predictor variables

As potential predictor variables, demographic characteristics, blood tests, and urine tests, routinely measured in clinical practice, were collected. These variables were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records, referencing the results from the day of admission for kidney biopsy or the day before the biopsy, with no post-biopsy results used. The demographic characteristics included age, sex, height, weight, and body mass index. The blood test items comprised white blood cells, hemoglobin, total protein, albumin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), uric acid, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase, total cholesterol (T-chol), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, C-reactive protein, immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin A, immunoglobulin M, C3, C4, and antinuclear antibodies. Urine test items included urine red blood cells (Urine RBC), urine protein/creatinine ratio, and urine protein per day (UP/day). eGFR was derived using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation modified by a Japanese coefficient26.

Urine RBC findings were confirmed by experienced urine sediment examination technicians at the hospital using microscopy and we scored on the following eight levels: 0 = < 1/high power field (HPF), 2.5 = 1–4/HPF, 7.5 = 5–9/HPF, 15 = 10–19/HPF, 25 = 20–29/HPF, 40 = 30–49/HPF, 75 = 50–99/HPF, 100 = ≥ 100/HPF. The potential predictor variables were reduced to prevent overfitting in the predictive models and reduce computational cost to ensure the events per variable ratio of at least 10 27. From the potential predictor variables, based on existing literature, all authors who are nephrologists discussed and selected age, albumin, eGFR, T-chol, IgG, C3, Urine RBC, and UP/day as the final predictor variables to be incorporated into each model.

Data preprocessing

The number and proportion of missing values for each variable are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Variables with less than 20% missing values were included in the analysis. The missing values were imputed using multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) to avoid potential bias by excluding patients with missing values. Continuous variables were imputed using predictive mean matching, and ten imputed datasets were created.

Outcome measures

The definitive diagnosis was defined based on a review by experienced nephrologists and renal pathologists using patient medical history, clinical tests, and pathology images from three types of kidney biopsies: light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. MCD was assigned a label of 1, while the other diagnosis was assigned a label of 0.

Model development and evaluation

We employed four machine learning algorithms—TabPFN, LightGBM, Random Forest, Artificial Neural Network—and logistic regression to develop predictive models. TabPFN is a pre-trained Transformer-based algorithm specialized for tabular data classification, known for its high learning speed and predictive accuracy on small datasets28. LightGBM combines the boosting technique with decision trees, sequentially building trees and correcting the errors of previous trees to improve model accuracy29. Random Forest combines the bagging technique with decision trees, independently training multiple trees and integrating their predictions to suppress overfitting and enhance predictive accuracy30. Artificial Neural Network consists of an input, hidden, and output layer and can handle complex relationships between inputs and outputs using non-linear activation functions31. Logistic regression is a widely used statistical linear model in the medical field for binary classification, generating probabilistic outputs that classify as positive if above a certain threshold and negative if below32. The optimal hyperparameters for the predictive models were tuned using Bayesian optimization with stratified 5-repeated 5-fold cross-validation. The hyperparameters of each model tuned are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

The performance of the predictive models was internally validated using stratified 5-repeated 5-fold cross-validation to maximize the use of available data. As performance metrics of model discrimination, we calculated the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC). AUROC and AUPRC were selected as they reflect performance across all classification thresholds and are less affected by class imbalance. The 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each metric were generated using 1000 bootstrap iterations with unique random seeds. To assess discriminability in detail, the deep ROC analysis was conducted to calculate the normalized group AUROC, mean sensitivity, and mean specificity across three groups according to the false positive rate33. Model calibration was evaluated using calibration plots, which plotted the actual positive fraction against the mean predicted probability for intervals divided into quintiles. The Brier score, which reflects the mean squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes, was used to evaluate model predictive performance and calibration simultaneously. The clinical utility of the models was assessed by decision curve analysis. Net benefit was calculated by subtracting the proportion of false positives from the proportion of true positives among all patients and comparing the relative harm of false positives.

Model interpretations

The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method was used to explore the interpretability of the models with high diagnostic performance. The SHAP method provides a unified approach for interpreting model predictions, offering consistent and locally accurate attribution values, i.e., the SHAP values, for each variable within the predictive model34. The role of each variable in predicting MCD can be explained as their collective contributions to the overall risk output for each case.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the differences in results caused by using imbalanced data. It is crucial for evaluating the potential overfitting of models in small data analyses. The analysis involved performing the same analysis and evaluation using data that had been oversampled with the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described using the mean and standard deviation for normally distributed data and the median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. For statistical comparisons, Student’s t-test was applied to normally distributed continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney U test to non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to categorical variables. Variables with two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For model development, we used the sklearn, tabpfn, lightgbm, and torch libraries in Python (version 3.10.12). For evaluation, we utilized the sklearn, optuna, deeproc, and shap libraries. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.2.2). The code related to the development and evaluation of the models can be accessed via the following GitHub link: https://github.com/Ryunosuke1219/MCD-diagnostic-prediction.

Results

Patient characteristics

After excluding cases under 18 years of age, cases without definitive diagnosis, and cases with multiple primary diagnosis, 248 cases were finally included. Of these, 82 cases (33%) of MCD followed by 51 cases (21%) of membranous nephropathy, 33 cases (13%) of lupus nephritis, 23 cases (9%) of diabetic nephropathy and 22 cases (9%) of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (Supplementary Table S3). The baseline characteristics of MCD and non-MCD patients are shown in Table 1.

Model performance

The AUROC for TabPFN was the highest at 0.915 (95% CI 0.896–0.932). There was no significant difference between TabPFN and the other models, including LightGBM, Random Forest, Artificial Neural Network, and logistic regression (Fig. 2). Similarly, the AUPRC for TabPFN was the highest at 0.840 (95% CI 0.807–0.872), with no significant difference compared to the other models (Fig. 3). The results of the deep ROC analysis for the normalized group AUROC, mean sensitivity, and mean specificity for each machine learning model are shown in Table 2. TabPFN had the highest normalized group AUROC in the groups with low and high false positive rates, while LightGBM had the highest in the group with intermediate false positive rates. Calibration plots indicated good calibration for all models, with Brier Scores ranging from 0.116 to 0.134 (Supplementary Fig. S1). In decision curve analysis, LightGBM had the highest net benefit in the low threshold probability range, TabPFN in the intermediate range, and logistic regression in the high range (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Model interpretations

The SHAP values were calculated for TabPFN, which demonstrated the best classification performance. The SHAP bar plot indicated the influential variables on the models’ predictions, with C3, T-chol, and Urine RBC being the top three predictor variables (Supplementary Fig. S3). Figure 4 shows the SHAP beeswarm plot, revealing Urine RBC, age, albumin, UP/day, and IgG between negative correlations. In contrast, C3 and T-chol positively correlated with MCD prediction. The SHAP dependence plot demonstrated complex relationships between the variables and MCD prediction (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Sensitivity analysis

The model’s performance was evaluated using the dataset adjusted with SMOTE. TabPFN achieved the highest performance with an AUROC of 0.953 (95% CI 0.945–0.961) and an AUPRC of 0.945 (95% CI 0.933–0.957), consistent with the primary analysis (Supplementary Fig. S5, S6).

Discussion

In this study, we developed and internally validated the predictive models based on four machine learning algorithms and logistic regression to diagnose MCD. The results showed that TabPFN had the highest performance in both AUROC and AUPRC, indicating its utility in predicting the diagnosis of MCD. The SHAP method revealed that the important predictor variables for TabPFN were C3, T-chol, and Urine RBC, which align with previous reports. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare and evaluate the performance of multiple machine learning models in diagnosing MCD. These findings suggest the potential of applying machine learning for non-invasive and reliable MCD diagnosis.

The need for non-invasive diagnostic methods for MCD has been discussed, but studies using predictive models are limited8,14,15,16,35,36. A study using logistic LASSO regression on 1009 adult nephrotic syndrome patients demonstrated the performance of AUROC 0.880, indicating the utility of predictive models for diagnosing MCD14. Another study on adult nephrotic syndrome patients showed high discrimination ability for MCD with an AUROC of 0.827 using two predictor variables16. In a study on a discrimination model between primary PLA2R-negative membranous nephropathy and MCD, logistic regression maintained an AUROC of 0.904 during development and 0.886 during validation15. While the previous studies have examined the effectiveness of predictive models in diagnosing MCD, all the models were classical statistical methods such as logistic regression. Logistic regression assumes linear relationships between outcomes and predictor variables, which, while advantageous for interpretability, may have limitations in predictive performance17,32. Although recent studies have increasingly used machine learning methods to model non-linear relationships and address predictive limitations, no such studies have been conducted for diagnosing MCD. Therefore, we conducted a comparative evaluation of the performance of multiple machine learning algorithms, not just logistic regression, in predicting MCD diagnosis, demonstrating the utility of machine learning. Previous studies did not share analytical code related to the predictive models. In this study, we made the code for model development and evaluation publicly available to promote open science. It will support further research and advance this field.

TabPFN demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to logistic regression and other machine learning algorithms for diagnosing MCD. Previous research showed that machine learning models often surpassed logistic regression in various tabular datasets37,38. TabPFN is a pre-trained Transformer-based machine learning algorithm specialized for tabular data classification. It outperformed existing machine learning algorithms like LightGBM and Random Forest across 18 datasets28. TabPFN demonstrated superior performance in predicting mortality and outcomes in neurosurgery and neuro-oncology39,40,41. The high performance of TabPFN in diagnosing MCD is consistent with these reports, highlighting the potential value of machine learning in non-invasive diagnostics. However, TabPFN did not show statistical significance compared to the other models, and the decision curve analysis indicated that other models also had clinical utility depending on the threshold setting. To ensure stable predictive performance and enhance statistical power, sufficient and appropriate sample sizes are needed42,43. Further large-scale studies are required to demonstrate robustness and generalizability in performance comparison between the algorithms.

We clarified the “black box” of TabPFN through the SHAP method, identifying C3 and T-chol, which positively correlated, and Urine RBC, which negatively correlated, as key predictors for MCD. The SHAP method is widely applied to interpret the contributions of predictor variables to model outputs34,44. C3 has not been identified as a specific marker for diagnosing MCD. Hypocomplementaemia, including low levels of C3, is associated with various kidney diseases such as lupus nephritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis, infection-related nephritis, and IgG4-related kidney disease45,46. In distinguishing PLA2R-negative membranous nephropathy from MCD, six variables, including C3, were reported as significant through univariate and multivariate logistic regression15. The C3 levels may help diagnose MCD because complement levels are associated with other causes of nephrotic syndrome. Another study that employed multivariate logistic regression to compare MCD and non-MCD groups identified T-chol and thrombin time as significant predictors16. The research comparing MCD and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis suggested that hematuria presence or absence was important for differentiation47,48,49. The key predictors identified in this study aligned with these studies. We additionally visualized the relationships between each variable and the predictions through the SHAP dependence plots. These insights deepen our understanding of how these variables correlate with MCD.

Our findings have important clinical implications. First, similar methods can be used to develop simple, accurate, and non-invasive predictive models for MCD, which have the potential for clinical application. Second, since our models employ variables routinely collected in clinical settings, their implementation does not require additional tests or expenses beyond standard procedures. Third, identifying key predictors and visualizing their relationship with MCD prediction can offer new insights for differentiating MCD in clinical practice.

This study has several limitations. First, it relies on data from a single center, needing external validation across various facilities. Since our model cannot ensure reliability and robustness outside of this institution, clinical application is not yet feasible. Evaluating the external validity of our model in diverse patient populations is essential. Second, it does not account for specific individual information such as race, ethnicity, geographic location, comorbidities, or health conditions. The models may not fully represent the diversity of the intended population, so careful consideration is crucial before clinical application. Third, due to the limited sample size and an imbalanced dataset, there might be insufficient statistical power and potential model overfitting, necessitating cautious interpretation of the evaluation results for each model. To address these concerns, we collected data from cases over 17 years from a high-volume medical institution, conducted the sensitivity analysis with oversampling, and minimized the number of predictive variables. Considering these limitations, future research should aim to develop models using large-scale data from multiple institutions and conduct broader external validation to assess the model’s generalizability and clinical utility.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the utility of the machine learning model TabPFN for diagnosing MCD using commonly available clinical data. Machine learning can potentially offer non-invasive and reliable tools for predicting MCD.

Data availability

The dataset cannot be disclosed as approval has not been received from the Ethics Committee of St. Marianna University Hospital. The code for analysis on the development and evaluation of the models is available at the following GitHub link: https://github.com/Ryunosuke1219/MCD-diagnostic-prediction.

References

Cameron, J. S. The nephrotic syndrome and its complications. Am. J. Kidney Dis.10, 157–171 (1987).

Smith, J. D. & Hayslett, J. P. Reversible renal failure in the nephrotic syndrome. Am. J. Kidney Dis.19, 201–213 (1992).

Waldman, M. et al. Adult minimal-change disease: clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.2, 445–453 (2007).

Poggio, E. D. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of native kidney biopsy complications. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.15, 1595 (2020).

Andrulli, S. et al. The risks associated with percutaneous native kidney biopsies: a prospective study. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl.38, 655–663 (2023).

Bai, M. et al. Serum IL-12p40: a novel biomarker for early prediction of minimal change disease relapse following glucocorticoids therapy. Front. Med. 9, (2022).

Garin, E. H. et al. Urinary CD80 is elevated in minimal change disease but not in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int.78, 296–302 (2010).

Ling, C. et al. Urinary CD80 levels as a diagnostic biomarker of minimal change disease. Pediatr. Nephrol.30, 309–316 (2015).

Tanaka, M. et al. Significance of urinary fatty acid-binding protein 4 level as a possible biomarker for the identification of minimal change disease in patents with nephrotic-range proteinuria. BMC Nephrol.21, 459 (2020).

Lodeweyckx, N., Wouters, K., Ledeganck, K. J. & Trouet, D. Biopsy or Biomarker? Children With Minimal Change Disease Have a Distinct Profile of Urinary Epidermal Growth Factor. Front. Pediatr. 9, (2021).

Segarra-Medrano, A. et al. Biological markers of nephrotic syndrome: A few steps forward in the long way. Nefrologia32, 558–572 (2012).

Cara-Fuentes, G. & Smoyer, W. E. Biomarkers in pediatric glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. Berl Ger.36, 2659–2673 (2021).

Weening, J. J. Will laboratory markers replace kidney biopsy in patients with nephrotic syndrome? Neth. J. Med.70, 107–108 (2012).

Yan, G. et al. Establishment of a novel nomogram for the clinically diagnostic prediction of minimal change disease, –a common cause of nephrotic syndrome. BMC Nephrol.21, 396 (2020).

Wu, F. et al. Development and validation of a discrimination model between primary PLA2R-negative membranous nephropathy and minimal change disease confirmed by renal biopsy. Sci. Rep.11, 18064 (2021).

Zhu, H. et al. A diagnostic model for minimal change disease based on biological parameters. PeerJ. 6, e4237 (2018).

Goldstein, B. A., Navar, A. M. & Carter, R. E. Moving beyond regression techniques in cardiovascular risk prediction: applying machine learning to address analytic challenges. Eur. Heart J.38, 1805–1814 (2017).

Wong, J., Horwitz, M. M., Zhou, L. & Toh, S. Using machine learning to identify health outcomes from electronic health record data. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep.5, 331–342 (2018).

Hobensack, M., Song, J., Scharp, D., Bowles, K. H. & Topaz, M. Machine learning applied to electronic health record data in home healthcare: a scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inf.170, 104978 (2023).

Tomašev, N. et al. A clinically applicable approach to continuous prediction of future acute kidney injury. Nature. 572, 116–119 (2019).

Kanda, E., Epureanu, B. I., Adachi, T. & Kashihara, N. Machine-learning-based web system for the prediction of chronic kidney disease progression and mortality. PLOS Digit. Health. 2, e0000188 (2023).

Noda, R., Ichikawa, D. & Shibagaki, Y. Machine learning-based diagnostic prediction of IgA nephropathy: Model development and validation study. Sci. Rep.14, 12426 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. Deep learning model for real-time prediction of intradialytic hypotension. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.16, 396 (2021).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD + AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ e078378 (2024).

Luo, W. et al. Guidelines for developing and reporting machine learning predictive models in biomedical research: A multidisciplinary view. J. Med. Internet Res.18, e323 (2016).

Matsuo, S. et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am. J. Kidney Dis.53, 982–992 (2009).

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R. & Feinstein, A. R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol.49, 1373–1379 (1996).

Hollmann, N., Müller, S., Eggensperger, K. & Hutter, F. TabPFN: A transformer that solves small tabular classification problems in a second. Preprint at (2023). http://arxiv.org/abs/2207.01848

Ke, G. et al. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc.; 2017).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn.45, 5–32 (2001).

Jain, A. K., Mao, J. & Mohiuddin, K. M. Artificial neural networks: A tutorial. Computer29, 31–44 (1996).

Cox, D. R. The regression analysis of binary sequences. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol.20, 215–242 (1958).

Carrington, A. M. et al. Deep ROC analysis and AUC as balanced average accuracy, for improved classifier selection, audit and explanation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.45, 329–341 (2023).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 4768–4777, (Curran Associates Inc.; 2017).

Hsiao, C. C. et al. (2018) Immunoglobulin E and G levels in predicting minimal change disease before renal biopsy. BioMed. Res. Int.2018, 1–6.

Shao, Y. N. et al. Serum immunoglobulin E can predict minimal change disease before renal biopsy. Am. J. Med. Sci.338, 264–267 (2009).

Caruana, R. & Niculescu-Mizil, A. An empirical comparison of supervised learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning - ICML ’06 161–168 (ACM Press; 2006).

Fernández-Delgado, M., Cernadas, E., Barro, S. & Amorim, D. Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems?. J. Mach. Learn. Res.15, 3133–3181 (2014).

Karabacak, M., Jagtiani, P., Carrasquilla, A., Shrivastava, R. K. & Margetis, K. Advancing personalized prognosis in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas through interpretable machine learning models. J. Neurooncol.164, 671–681 (2023).

Karabacak, M. & Margetis, K. Development of personalized machine learning-based prediction models for short-term postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing cervical laminoplasty. Eur. Spine J.32, 3857–3867 (2023).

Karabacak, M. et al. Development and internal validation of machine learning models for personalized survival predictions in spinal cord glioma patients. Spine J.24, 1065–1076 (2024).

Cui, Z. & Gong, G. The effect of machine learning regression algorithms and sample size on individualized behavioral prediction with functional connectivity features. NeuroImage. 178, 622–637 (2018).

Raudys, S. J. & Jain, A. K. Small sample size effects in statistical pattern recognition: Recommendations for practitioners. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.13, 252–264 (1991).

Thorsen-Meyer, H. C. et al. Dynamic and explainable machine learning prediction of mortality in patients in the intensive care unit: A retrospective study of high-frequency data in electronic patient records. Lancet Digit. Health2, e179–e191 (2020).

Hebert, L. A., Cosio, F. G. & Neff, J. C. Diagnostic significance of hypocomplementemia. Kidney Int.39, 811–821 (1991).

Saeki, T. & Kawano, M. IgG4-related kidney disease. Kidney Int.85, 251–257 (2014).

Habib, R. Focal glomerular sclerosis. Kidney Int.4, 355–361 (1973).

Korbet, S. Clinical picture and outcome of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl.14, 68–73 (1999).

Ozeki, T. et al. Clinical manifestations of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in Japan from the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry: Age stratification and comparison with minimal change disease. Sci. Rep.11, 2602 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate Ms. Yoshiko Ono and Ms. Mami Ohori for their invaluable contributions to patient data collection. Their commitment and hard work played a crucial role in the progress of our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.N. designed the research plan and analyzed the data. R.N., D.I., and Y.S. participated in the writing of the paper. R.N., D.I., and Y.S. participated in approving the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noda, R., Ichikawa, D. & Shibagaki, Y. Machine learning-based diagnostic prediction of minimal change disease: model development study. Sci Rep 14, 23460 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73898-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73898-4