Abstract

Prior research has demonstrated an association between sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor and a reduced incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF). Given the established link between mitochondrial dysfunction and AF, this study aimed to explore the impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on AF burden and plausible antiarrhythmic mechanisms in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs). Patients with atrial high-rate episodes (AHREs) detected by CIEDs were randomized to receive either 10 mg of dapagliflozin or a placebo for 3 months. AF burdens were quantified via CIEDs interrogations as AHREs duration, percentage, and number of episodes at baseline and after 3 months of treatment. Mitochondrial parameters, cellular oxidative stress, and norepinephrine levels were measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). A total of 54 patients with CIEDs were enrolled in the study. Among them, 36 patients (66.7%) had a history of clinical AF, and 9 patients (16.7%) had diabetes mellitus. After 3 months of the assigned treatment, the median longest AHRE duration decreased similarly in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups (-77.0 vs. -162.0 min, p = 0.442). Clinical AF, as opposed to subclinical AF, was independently linked to decreased basal respiration and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. Although the changes in AHREs burden over the 3 months did not significantly differ between the dapagliflozin and placebo groups, dapagliflozin significantly decreased the number of AHREs per month by 2.2 episodes among patients with clinical AF, whereas the placebo group experienced an increase of 0.6 episodes (p = 0.048). Additionally, dapagliflozin significantly reduced cellular oxidative stress (from 26840 to 18164 arbitrary units, p = 0.049) and improved mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity (SRC) percentage (from 166 to 202%, p = 0.016) in patients with clinical AF. Dapagliflozin did not significantly reduce the longest AHRE duration in patients with CIED. However, in the subgroup of patients with clinical AF, dapagliflozin reduced the number of AHREs potentially via reduction of cellular oxidative stress and enhancement of mitochondrial function.

The study protocol was registered at the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR identification number TCTR20210315003) on March 15, 2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, impacting approximately 3.6 million individuals worldwide. It is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, heart failure, vascular dementia, impaired quality of life, hospitalizations, and death1. Current anti-arrhythmic drugs for AF rhythm control have a success rate of 30–50% in maintaining long-term sinus rhythm, while AF ablation achieves approximately a 50–70% success rate depending on the type of AF2. Therefore, the search for additional treatment modalities to improve rhythm control success continues. Anti-diabetic medications are associated with various risks of new-onset AF. Metformin and thiazolidinediones are associated with a reduced risk of AF, whereas insulin is linked to an increased risk of AF3,4.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have recently become an attractive upstream target for antiarrhythmic modulation, given their additional cardiovascular benefits in heart failure, cardiovascular death, and all-cause mortality in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients5,6,7,8. SGLT2 inhibitor has been shown in post-hoc analysis to decrease the incidence of AF and atrial flutter (AFL) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM)9. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors can decrease sympathetic overactivity10, restore superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity11, improve atrial mitochondrial respiratory function, membrane potential, fusion, fission, and biogenesis, prevent left atrial dilatation and interstitial atrial fibrosis, and reduce AF inducibility11. However, clinical data on the potential antiarrhythmic effect of SGLT2 inhibitor are limited to observational studies and non-continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring. Additionally, mechanistic insights into the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on AF burden in humans are lacking. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on AF burden in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) and investigated the plausible mechanisms. Furthermore, we explored whether mitochondrial function differs between different types of AF.

Methods

Trial design

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. Randomization was performed using a blinded allocation, stratified based on a history of DM diagnosis.

Patients

We enrolled adults (≥ 18 years old) who had dual chamber CIEDs for at least 3 months with atrial high-rate episodes (AHREs) detected by CIEDs. AHREs were defined as an atrial rate of > 170 beats per minute for > 6 min. Exclusion criteria included: (1) current use of SGLT2i, (2) permanent or long-standing persistent AF, (3) estimated glomerular filtration rate < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2, (4) pregnancy or lactation, (5) systolic blood pressure < 95mmHg or symptoms of hypotension, (6) recent hospitalization due to acute coronary syndrome, percutaneous coronary intervention, cardioversion, or coronary artery bypass graft within 3 months, (7) atrial arrhythmia ablation within previous 3 months or currently planned, (8) bladder cancer, (9) history of genital infection within 3 months, (10) history of frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs) (≥ 2 UTIs in 6 months or ≥ 3 UTIs in 12 months), or 1(1) type 1 DM.

Definition

Clinical AF was defined as symptomatic or asymptomatic AF documented by surface ECG, with a minimum ECG tracing duration of 30 s or an entire 12-lead ECG1.

AHRE was defined as events detected by CIEDs with an atrial lead that met programmed or specified criteria, including an atrial rate exceeding 170 beats per minute for more than 6 min1. AHREs needed to be reviewed by physicians to exclude electrical artifacts. Subclinical AF in this study was defined as the presence of AHRE.

Trial procedures

The informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). Randomization was performed by research coordinators using a web-based platform, www.randomized.org, which uses the JavaScript Math.random() function to generate a random assignment in blocks of 4. Patients were then randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by the presence of type 2 DM, in a double-blinded fashion to receive dapagliflozin (Forxiga™) 10 mg daily or a placebo for 3 months. The use of other glucose-lowering agents (except opened-label SGLT2i) was at the treating physician’s discretion. Patients attended clinic visits at 3 months.

At baseline, CIED interrogation was conducted to assess AHRE burden before the initiation of the study drug. All AHRE tracings were reviewed by clinical cardiac electrophysiologists to exclude signal artifacts. Treating physicians obtained baseline clinical characteristics and echocardiographic parameters from patients and electronic medical records during the initial visit. Research nurses performed blood draws for the metabolic panel, norepinephrine level, cellular oxidative stress, mitochondrial dynamics, and mitochondrial function.

At the 3-month face-to-face visit, CIED interrogation was repeated to measure the AHRE burden over the preceding 3 months while on the study drug. Clinical data, including vital signs, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, the presence of abnormal symptoms (e.g. palpitations, dizziness, chest pain, dyspnea, legs swelling, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or dysuria), and adverse events were obtained by physicians. We assessed medication adherence pill counting. Blood samples were drawn for the metabolic panel, norepinephrine levels, cellular oxidative stress, mitochondrial dynamics, and mitochondrial function during this 3-month clinic visit.

Placebo tablets, composed of starch, were visually indistinguishable from dapagliflozin tablets. All healthcare personnel, data collectors, and investigators involved in the study were blinded to the participant’s treatment allocation. In the event of a serious adverse event or an adverse event leading to discontinuation of the study drug, participants were permitted to discontinue the drug under the guidance of the investigators; however, the treatment group assignment remained concealed from both participants and investigators. Investigators, blinded to the trial-group assignments, reviewed and classified end-point events and laboratory results based on prespecified definitions. Blinding codes were withheld from the investigators conducting the data analysis until the analysis was fully completed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the longest AHRE duration. Secondary outcomes included other AF burden measurements (percent time in AHREs, number of AHREs per month), oxidative stress parameters (cellular and mitochondrial oxidative stress), norepinephrine level, and mitochondrial function parameters (mitochondrial mass, ATP production, maximal respiration, %spare respiratory capacity (SRC)). Tertiary outcomes derived from a cross-sectional analysis comparing baseline cellular oxidative stress and mitochondrial function between clinical AF and subclinical AF patients.

Blood measurements

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolation

Twenty mL of blood samples were collected. After initial centrifugation (1000G for 10 min), white and red blood cells were collected and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The diluted cells were then layered on top of the Ficoll-Paque reagent (Histopaque, Sigma-Aldrich, MI, USA) and centrifuged at 400G for 30 min. The PBMC ring at the Ficoll-plasma interface was aspirated and washed twice with 10 mL of PBS. After the final centrifugation at 1000G for 10 min, the PBMCs were counted using a hemocytometer. The viability was measured using Trypan blue staining, and 2 × 105 cells of viable PBMCs were used12. The isolated PBMCs typically comprise 50–70% T cells, 4–9% B cells, 4–15% NK cells, 10–20% monocytes, and 1–2% dendritic cells13.

Cellular oxidative stress determination

The cellular oxidative stress levels were determined using a Dichlorohydro-Fluorescein Diacetate dye on PBMCs (DCFH-DA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). DCF fluorescent intensity was detected at λex 485 nm, and λem 530 nm using flow cytometry (BD FACS Celesta, San Jose, California, USA). Detailed methods were previously described in our literature12.

Mitochondrial parameters

The mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in freshly isolated PBMCs were assessed using MitoSOX Red staining (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA). Mitochondrial mass was determined using Mitotracker Deep Red Dye (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA). The ratio of MitoSOX and Mitotracker Deep Red-stained PBMCs was used as an indicator for mitochondrial ROS production. Oxygen consumption during the Mito Stress test was measured using the Agilent Seahorse XFe96 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The protocols used were previously published in our prior literature12.

Norepinephrine level

A non-competitive enzyme immunoassay (CatCombi ELISA, IBL International GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) kit was used for quantitative determination of plasma norepinephrine levels. Detailed methods were described in the previous study14.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables and as median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables. Baseline characteristics between groups were compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables, Student’s t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables.

The primary endpoint, longest AHRE duration, and secondary endpoints were analyzed based on the intention-to-treat principle. Since we assessed the effects of drug treatment before and after in the same group of participants, we utilized paired t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables. A pre-specified subgroup analysis was conducted based on clinical AF history and DM status.

We originally intended to recruit 166 patients to obtain an alpha level of 0.05 and 80% power, expecting a 25% reduction in AT/AF burden between SGLT2 inhibitors and placebo15. However, due to the Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and challenges with slow recruitment, the investigators terminated enrollment at 54 patients. The final sample size still provides 90% power to detect a 12% reduction in mitochondrial parameters and oxidative stress16. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 24.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Three out of 54 patients (5.6%) were lost to follow-up. For missing data, a complete case analysis approach was employed. While this may introduce potential bias, the exclusion of 5–10% of data with missing values is generally considered acceptable17,18.

Results

Baseline characteristics

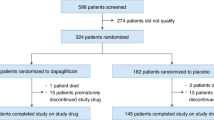

Between March 2021 and February 2024, 183 CIED patients were screened, 72 patients had AHREs, and 54 patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. Of these, 27 patients were randomized to receive dapagliflozin, and 27 received a placebo. The mean age was 69.9 ± 12.8 years, and 57.4% were male. There were 26 (48.1%) with hypertension, 12 (22.2%) with valvular heart disease, and 9 (16.7%) patients with DM. About two-thirds of patients (36/54, 66.7%) had a history of clinical AF. Echocardiographic parameters showed a normal mean left ventricular ejection fraction of 59.9% and left atrial anteroposterior diameter of 38.9 millimeters. Median AHREs burden measured as the longest episode, percentage, and episode per month were 539 min (~ 9 h), 2.0%, and 6.8 times per month, respectively. Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, functional class, medications, baseline oxidative stress, and mitochondrial parameters, were similar between the two groups (Table 1)

Primary and secondary outcomes

AF burden

At baseline, the median longest AHRE duration was 620.5 (IQR 68.8–2565.0) minutes in the dapagliflozin group and 466.0 (IQR 24.0–1117.5) minutes in the placebo group (p = 0.365). The baseline AHREs percentage comparing between dapagliflozin and placebo group (2.0, IQR 1.0–17.0% vs. 2.8, IQR 1.0–8.8%, p = 0.896) and AHREs per month (6.8, IQR 1.1–32.2 episodes vs. 6.0, IQR 0.9–25.9 episodes, p = 0.734) were also similar.

After 3 months of the assigned treatment, the median AHRE longest duration decreased similarly among the dapagliflozin and placebo group (− 77.0 vs. − 162.0 min, p = 0.442). Both groups showed no significant change in the median AHREs percentage or median number of episodes per month (Table 2).

In subgroup analysis among CIED patients with clinical AF (Table 3), dapagliflozin significantly reduced AHREs per month while this was not the case in the placebo group (− 2.2 versus + 0.6 AHREs per month, p = 0.048).

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial function

At baseline, there were no significant differences in cellular oxidative stress, mitochondrial ROS, mitochondrial mass, or mitochondrial function between the dapagliflozin and placebo groups. After 3 months, the mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity (SRC) percentage was significantly increased in the dapagliflozin group (from 162.1 to 203.2%, p = 0.003), whereas it remained unchanged in the placebo group (Fig. 1).

In patients with clinical AF, dapagliflozin resulted in a significant increase in SRC percentage (from 165.7 to 201.7%, p = 0.016) and a decrease in cellular oxidative stress (from 26840.5 to 18164.0 arbitrary unit, p = 0.049). Additional parameters such as cellular oxidative stress, mitochondrial oxidative stress, mitochondrial mass, mitochondrial oxidative stress-to-mass ratio, non-mitochondrial respiration, basal respiration, proton leak, ATP production, and percentage coupling efficiency showed no significant differences between the dapagliflozin and placebo groups.

Norepinephrine level

Plasma norepinephrine levels did not significantly change in either group over the study period. After 3 months of treatment, norepinephrine levels decreased from 298.9 to 288.7 pg/mL (mean difference − 10.2, 95% CI − 62.3 to 41.9 pg/mL, p = 0.690) in the dapagliflozin group. In the placebo group, norepinephrine levels decreased from 429.7 to 414.8 pg/mL (mean difference − 14.8, 95% CI − 112.6 to 82.9 pg/mL, p = 0.752).

Tertiary outcomes: comparisons between clinical and subclinical AF

Patients with clinical AF (n = 36) had significantly higher AHREs percentages compared to those with subclinical AF (n = 18) (11.1 ± 14.3 vs. 2.9 ± 5.5%, p = 0.005). Furthermore, clinical AF was independently associated with lower ATP production (57.3, IQR 24.7–73.2 vs. 78.6, IQR 45.7–112.0 pmol/min, p = 0.014) and basal respiration (72.1, IQR 47.4–94.4 vs. 97.2, IQR 52.1–152.6 pmol/min, p = 0.020) compared to subclinical AF (Table 4).

Adverse events

No mortality occurred during the study. Two (3.7%) patients in the placebo group were admitted to the hospital due to acute kidney injury and supratherapeutic international normalized ratio (INR), but none in the SGLT2 inhibitor group. Six (11.1%) patients in each group equally reported minor side effects e.g. increased urination, fatigue, rash, decreased libido, decreased appetite, myalgia, and dizziness. Two (3.7%) patients randomly assigned to dapagliflozin and 3 (5.5%) patients randomly assigned to placebo prematurely and permanently discontinued the study drug.

Discussion

Our study reports 3 key findings as follows: (1) Although dapagliflozin did not reduce AHREs burden in the overall CIED population as compared to placebo, it did decrease the number of AHREs per month among CIED patients with clinical AF; (2) After 3 months of treatment with dapagliflozin, SRC percentage showed significant improvement, whereas no such improvement was observed in the placebo group; (3) In the subgroup analysis of patients with clinical AF, dapagliflozin significantly lowered cellular oxidative stress and increased SRC percentage compared to the placebo; (4) Patients with clinical AF had higher baseline AF burden (total AHREs percentage) than patients with subclinical AF; and (5) Baseline mitochondrial basal respiration and ATP production among patients with clinical AF were lower than patients with subclinical AF.

A systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that SGLT2 inhibitor was associated with lower total AF events19. However, the AF events reported in the included studies were identified only through reports of serious adverse events, adverse events leading to discontinuation of the study drug, or other adverse events documented at the discretion of the treating physician. This method may result in an underestimation of AF incidence. Additionally, not all AF types carry the same risk of stroke or systemic embolism. Persistent AF is linked to a higher stroke risk compared to paroxysmal AF (10.1% versus 6.0%, respectively, p = 0.009)20. A greater AF burden has been correlated with increased risks of stroke, heart failure, and mortality21. Our randomized controlled trial revealed a beneficial effect of SGLT2 inhibitor on the number of AHREs per month reduction among patients with clinical AF, which is consistent with a previous observational study that showed an association between SGLT2 inhibitor use and a decrease in total number of atrial arrhythmic episodes in patients implanted with a CIED22. Several factors besides the SGLT2 inhibitor could have influenced the AHRE burden, such as underlying diabetes mellitus, HbA1C levels, other glucose-lowering medications, age, GFR, and LVEF. However, these variables were comparable between the SGLT2 inhibitor and placebo groups.

Given the observation that there was no expression of SGLT2 at both gene and protein levels in cardiac tissues of human hearts, the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitor on AF were postulated to be from indirect metabolic or hemodynamics, such as weight reduction, decrease in epicardial adipose tissue, improvement in diastolic function, reversal of adverse structural and electrical remodeling, rather than the direct ‘on-target’ effects on the cardiomyocyte23. Inhibition of sodium-hydrogen exchanger (NHE) activity by SGLT2 inhibitor has been proposed as one of the possible indirect anti-atrial arrhythmic effects, however, the results of NHE inhibitors from animal models of AF have been mixed23. Shao and colleagues demonstrated that empagliflozin could improve mitochondrial respiration, and reduce oxidative stress, atrial fibrosis, and AF inducibility in diabetic rats11. This is consistent with our findings demonstrating that dapagliflozin significantly improved mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity, reduced cellular oxidative stress, and decreased AHREs burden among patients with clinical AF. Baseline mitochondrial mass did not differ between patients with clinical AF versus subclinical AF. Also, there was no significant difference in mitochondrial mass after treated with SGLT2 inhibitor versus placebo. One study performed tachypacing in HL-1cardiomyocytes to simulate atrial tachyarrhythmias, they showed that tachypacing did not affect mitochondrial mass, but it compromised bioenergetic function by transitioning from a tubular to a fragmented mitochondrial network (mitochondrial fragmentation)24.

In our study, we evaluated mitochondrial function using PBMCs rather than endomyocardial tissue biopsies. While cardiac tissues provide a more direct assessment of mitochondrial function and oxidative stress within the heart, PBMCs offer a less invasive and more feasible alternative in clinical practice. Alfatni et al. demonstrated a marked reduction in mitochondrial respiratory chain complex II activity in PBMCs following heart transplantation, consistent with earlier observations of diminished complex I and II activity in endomyocardial tissue from patients with cardiac allograft vasculopathy25. Furthermore, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species levels in PBMCs have been shown to correlate directly with plasma B-type natriuretic peptide levels, advanced heart failure (NYHA class III), and inversely with peak oxygen uptake26.

Herat and colleagues demonstrated that dapagliflozin resulted in significantly reduced norepinephrine levels in the kidney tissue of hypertensive mice10. However, in our study dapagliflozin did not significantly decrease norepinephrine level. This may be explained by various factors among individual patients that could affect norepinephrine levels, such as heart failure, high blood pressure, kidney disease, stress-activated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, or autonomic dysfunction, which might overshadow the effects of SGLT2i. An in vitro, in vivo, and human studies have shown the association between mitochondrial dysfunction and AF27. Wiersma and colleagues demonstrated a progressive increase in mitochondrial stress-related chaperones (HSP60) and lower ATP production in HL-1 atrial cardiomyocytes that received prolonged tachypacing to simulate atrial arrhythmias24. This supports our findings which showed a lower baseline mitochondrial basal respiration, and lower ATP production among clinical AF patients which had a higher baseline AF burden than the subclinical AF group.

Strengths of our study include (1) study design that was a randomized double-blind placebo control trial; (2) AF burden that was measured by AHREs from CIED which provided continuous monitoring and various aspects of AF burden (longest episode, percentage of burden, and number of episodes per month); and (3) providing information regarding plausible mechanisms of SGLT2 inhibitor in association with AF burden reduction. Several limitations are noted as follows: (1) The study was terminated early with a smaller sample size than originally planned due to COVID-19 and recruitment challenges, resulting in insufficient power to detect differences in AHRE burden. Although the final sample size provides adequate power to detect changes in mitochondrial parameters and oxidative stress, the robustness and generalizability of the findings might be compromised. Future studies will require a minimum of 174 patients to achieve 80% power to detect a 25% reduction in AHRE burden with the study drug while accounting for a 5% loss to follow-up, and (2) AF burden may have self-variation independent of the treatment. However, this issue was partly accounted for by having a placebo group and averaging AF burden during a 3-month follow-up period.

Conclusions

Dapagliflozin did not significantly reduce the longest AHRE duration in patients with CIED. However, in the subgroup of patients with clinical AF, dapagliflozin reduced the number of AHREs potentially through the reduction of cellular oxidative stress and enhancement of mitochondrial function. Notably, baseline basal respiration and ATP production were significantly lower in patients with clinical AF compared to those with subclinical AF. These observations may partly explain the differential response to dapagliflozin between the two groups. Further large-scale, long-term studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

Data availability

This study does not cover data posting in public databases. However, data are available upon request should be sent to bwanwarang@yahoo.com (Corresponding author).

Abbreviations

- AHREs:

-

atrial high-rate episodes

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- AFL:

-

Atrial flutter

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CIED:

-

Cardiovascular implantable electronic devices

- DCF:

-

Dichlorofluorescein

- DCFH:

-

DA-Dichlorohydro-Fluorescein Diacetate

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- NHE:

-

Sodium-hydrogen exchanger

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer saline solution

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SGLT2:

-

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- SRC:

-

Spare respiratory capacity

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

References

Hindricks, G. et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612 (2020).

Joglar, J. A. et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice guidelines. Circulation. 149, e1–e156. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193 (2023).

Nantsupawat, T., Wongcharoen, W., Chattipakorn, S. C. & Chattipakorn, N. Effects of metformin on atrial and ventricular arrhythmias: evidence from cell to patient. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-020-01176-4 (2020).

Wang, A., Green, J. B., Halperin, J. L. & Piccini, J. P. Sr. atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, 1107–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.020 (2019).

McMurray, J. J. V. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl. J. Med. 381, 1995–2008. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1911303 (2019).

Neal, B. et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 644–657. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1611925 (2017).

Wiviott, S. D. et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1812389 (2019).

Zinman, B., Empagliflozin. et al. Cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2117–2128. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 (2015).

Zelniker, T. A. et al. Effect of Dapagliflozin on Atrial Fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus: insights from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 Trial. Circulation. 141, 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044183 (2020).

Herat, L. Y. et al. SGLT2 inhibitor-induced sympathoinhibition: a novel mechanism for cardiorenal protection. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 5, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.11.007 (2020).

Shao, Q. et al. Empagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor, alleviates atrial remodeling and improves mitochondrial function in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 18, 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-019-0964-4 (2019).

Wittayachamnankul, B. et al. High central venous oxygen saturation is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in septic shock: a prospective observational study. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 24, 6485–6494. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.15299 (2020).

Kleiveland, C. R. et al. In The Impact of Food Bioactives on Health: in vitro and ex vivo models (ed. Verhoeckx, K.) 161–167 (2015).

Westermann, J., Hubl, W., Kaiser, N. & Salewski, L. Simple, rapid and sensitive determination of epinephrine and norepinephrine in urine and plasma by non-competitive enzyme immunoassay, compared with HPLC method. Clin. Lab. 48, 61–71 (2002).

Healey, J. S. et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105575 (2012).

Iannantuoni, F. et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor Empagliflozin ameliorates the Inflammatory Profile in type 2 Diabetic patients and promotes an antioxidant response in leukocytes. J. Clin. Med. 8https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8111814 (2019).

Bennett, D. A. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Aust N Z. J. Public. Health. 25, 464–469 (2001).

Schafer, J. L. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 8, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/096228029900800102 (1999).

Pandey, A. K. et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitors and atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e022222. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.022222 (2021).

Koga, M. et al. Higher risk of ischemic events in secondary prevention for patients with persistent than those with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 47, 2582–2588. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013746 (2016).

Brown, E., Rajeev, S. P., Cuthbertson, D. J. & Wilding, J. P. H. A review of the mechanism of action, metabolic profile and haemodynamic effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 21 (Suppl 2), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13650 (2019).

Younis, A. et al. Effect of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on atrial tachy-arrhythmia burden in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 34, 1595–1604. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.15996 (2023).

Shetty, S. S. & Krumerman, A. Putative protective effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on atrial fibrillation through risk factor modulation and off-target actions: potential mechanisms and future directions. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01552-2 (2022).

Wiersma, M. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction underlies cardiomyocyte remodeling in experimental and clinical atrial fibrillation. Cells. 8https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8101202 (2019).

Alfatni, A. et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells mitochondrial respiration and Superoxide Anion after Heart Transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 11https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237247 (2022).

Shirakawa, R. et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in blood cells is associated with disease severity and exercise intolerance in heart failure patients. Sci. Rep. 9, 14709. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51298-3 (2019).

Mason, F. E., Pronto, J. R. D., Alhussini, K., Maack, C. & Voigt, N. Cellular and mitochondrial mechanisms of atrial fibrillation. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 115, 72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-020-00827-7 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to all colleagues at the Cardiac Electrophysiology Research and Training (CERT) Centre, Chiang Mai University, for their invaluable support and contributions to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, the Fundamental Fund 2023 project number 4368887, Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), the Research Chair Grant from the National Research Council of Thailand (NC), the Distinguished Research Professor Grant from the National Research Council of Thailand (SCC), and the Chiang Mai University Center of Excellence Award (NC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TN, WW, SCC, and NC participated in the conception and design of the study. TN, NA, WW, AP, and NP gathered and analyzed data. TN and NA wrote the manuscript. TN, WW, SCC, and NC revised the whole writing process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Chiang Mai University (certificate of approval No.041/2021). The investigations were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nantsupawat, T., Apaijai, N., Phrommintikul, A. et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor on atrial high-rate episodes in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic device: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 14, 27649 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74631-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74631-x